1. Introduction

In the field of agricultural value chains, research has predominantly focused on global chains, emphasizing social and environmental impacts [

1], large-scale production systems [

2], innovation, technology, and access to major markets [

3]. Consequently, there are relatively few studies on small-scale agriculture that explore how value chains operate to improve efficiency and sustainability by integrating multiple dimensions such as social, economic, ecological, and institutional aspects [

4,

5]. In contrast, studies on value networks (VNs) often adopt a social network perspective to understand the production dynamics of maize, coffee, cocoa, horticultural crops, fruits, tubers, and biomass at a small scale, highlighting the importance of actor interactions in advancing the sustainability of value networks [

3,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. In this regard, the concept of social networks places particular emphasis on social capital as an indispensable variable for the sustainability of value networks [

10,

11].

Examples of this trend have been observed in India, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Jamaica, where producers tend to organize into social networks with the aim of ensuring the transformation, distribution, and commercialization of their products [

5,

10,

12,

13]. These networks are generally structured through organizations, guilds, or associations, serving as collaborative models based on agricultural enterprises and cooperatives designed to strengthen bargaining power and enhance effective integration into value chains by pooling sufficient production volumes and subsequently enabling value aggregation and commercialization with strategic partners [

14]. Similar characteristics are found in small-scale agriculture in Latin America, although social relations of production, processing, and commercialization tend to be weaker and add less value in this region [

15,

16]

In Colombia, the concept of value networks has rarely been applied to explain production systems, despite the country’s significant representation of small-scale agricultural producers, who contribute between 50% and 68% of national food production [

17]. Nonetheless, the concept has been applied in the case of biomass-based value networks such as that involving cassava (

Manihot esculenta) [

18]. This gap has limited the generation of knowledge about the challenges faced by small producers and emerging agri-food systems, such as Amazonian fruits, which lack the level of technological development and sophistication required to sustain the long-term dynamics of sustainable development and ecosystem conservation [

19].

Given the potential of emerging production systems such as Amazonian fruits and their role in forest conservation, the Colombian government—aligned with zero-deforestation objectives and supported by international cooperation—has prioritized sustainable production and forest management as key strategies to strengthen forest governance, rural economies, and the stabilization of the agricultural frontier in the Colombian Amazon. These initiatives aim to create sustainable opportunities for small-scale producers operating in contexts characterized by low productivity, limited infrastructure, and restricted capacity for value aggregation [

20].

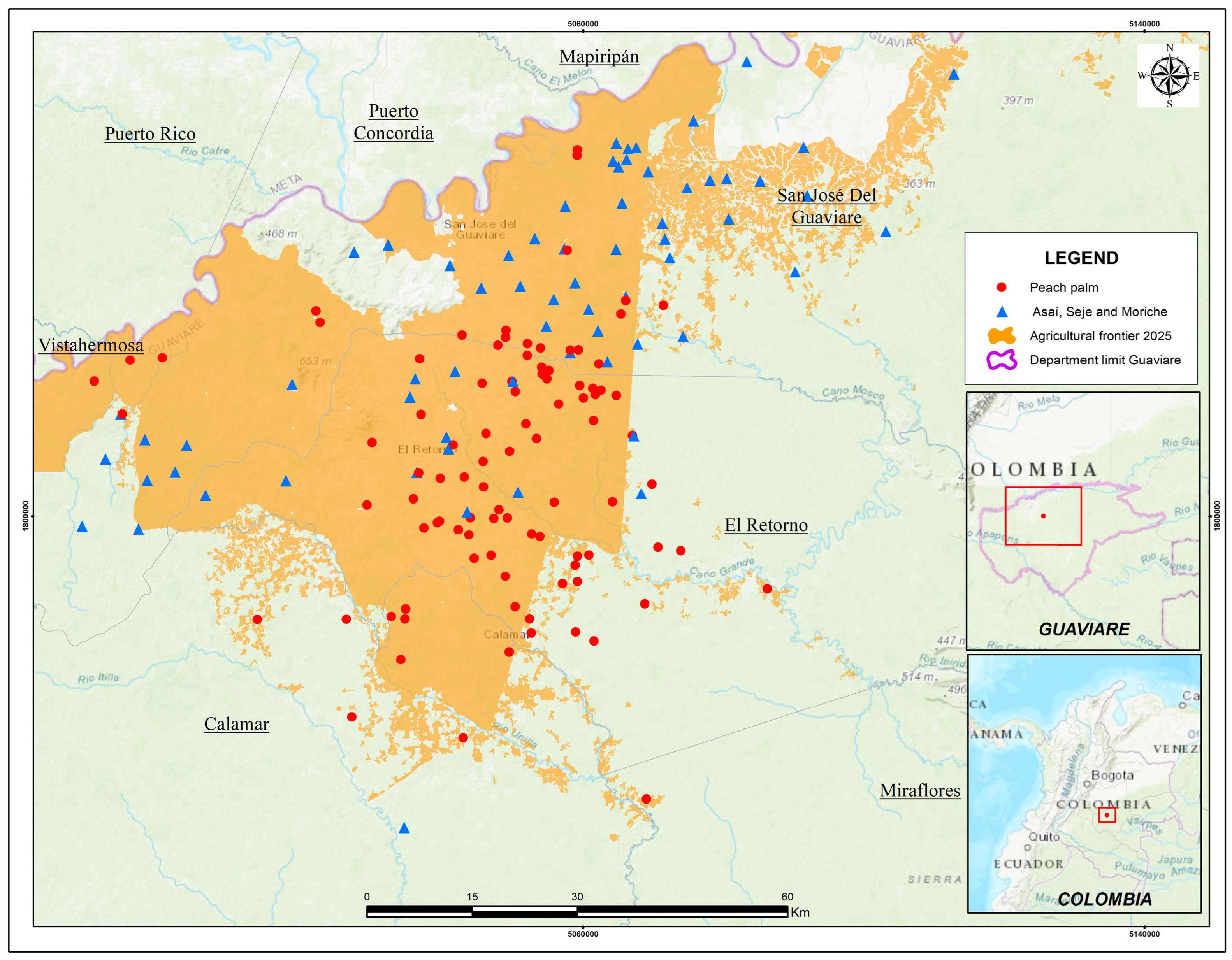

Based on studies by CIAT [

20,

21], the Amazonian Institute of Scientific Research Sinchi [

22,

23,

24,

25] in the department of Guaviare, Amazonian fruits such as Peach palm (

Bactris gasipaes), Asaí (

Euterpe precatoria), Seje (

Oenocarpus bataua), and Moriche (

Mauritia flexuosa) have been identified as viable and sustainable economic alternatives to address deforestation, the overexploitation of natural resources, unsustainable agricultural practices, and the effects of climate change [

26]. However, these initiatives are embedded in complex networks of social, institutional, and commercial relations that determine their viability and remain understudied in academic research. While existing studies by research institutes have addressed dimensions such as profitability, production volumes, processing, commercialization, and sustainability, a broader perspective is needed—one that incorporates governance, inter-institutional coordination, and multi-actor articulation—dimensions that remain insufficiently explored [

27,

28].

This productive and economic potential is also reflected in Guaviare’s annual production statistics, identified via departmental agricultural assessments carried out by the Agricultural Planning Unit of Colombia (UPRA), when compared to other crops promoted under zero-deforestation and peacebuilding strategies [

29]. A notable example is the Peach palm, whose production volume increased significantly from 602 tons in 2014 to 9552 tons in 2021. Similarly, non-timber forest products such as Asaí showed a marked increase, from 9 to 80 tons between 2014 and 2017 [

22]. In contrast, cocoa (

Theobroma cacao)—a crop promoted by international cooperation as part of a zero-deforestation value chain—has experienced a decline in production over the past two years, decreasing from 69,040 to 62,158 tons, a trend mainly attributed to climate variability and, in particular, high levels of precipitation. Another crop is rubber (

Hevea brasiliensis), whose production rose from 55 tons in 2007 to 1200 tons in 2018. However, since 2020, this crop has suffered severe losses due to a phytosanitary disease that, by 2025, had affected 60% of plantations [

21].

The rapid expansion of these “novel foods” in local markets has configured an emerging trend at both the regional and national levels. This process has encouraged actors within these VNs to organize into cooperatives and associations to consolidate production volumes, process products, and commercialize them through strategic alliances and agreements, most of which are informal in nature. Nevertheless, these processes remain incipient, and there is limited understanding of the network-level factors that influence consolidation and long-term social, economic, and ecological sustainability.

Historically, research and economic analysis in this region have been grounded in linear methodologies like the value chain and supply chain. These frameworks are primarily concerned with efficiency, margin maximization, and logistics, emphasizing unidirectional and hierarchical transactions [

27]. Conversely, the emerging agri-food systems in Guaviare, driven by small-scale producers and regional businesses, function according to a fundamentally distinct logic not adequately addressed by linear models. Their sustainability and prosperity are conditional upon variables requiring the adoption of a value network (VN) framework. In this context, the value network perspective has not been utilized to understand the interactions of actors driving these emerging economies. This is primarily attributed to the insufficiency of analytical and methodological tools adapted to these specific socio-environmental and cultural contexts.

In response to this local production dynamic, the present study employs a value network approach to analyze value creation through the dynamic structures established among producers, intermediaries, suppliers, and consumers [

28]. According to Ricciotti [

27], this logic is grounded in cooperation aimed at improving processes through the exchange of knowledge and information flows, with the potential to generate commercial and competitive impacts in the marketplace. The study also builds on a social network perspective as an analytical tool to examine dynamic interactions and horizontal collaborative relationships among multiple actors interconnected through flows of information, resources, and shared objectives [

30].

This analytical choice seeks to capture the associative, dynamic, and territorially embedded nature of these networks, as a first step toward understanding how they function, what their strengths and weaknesses are, and how they may consolidate as an ecologically and economically viable strategy that contributes to the livelihoods of rural communities.

3. Results

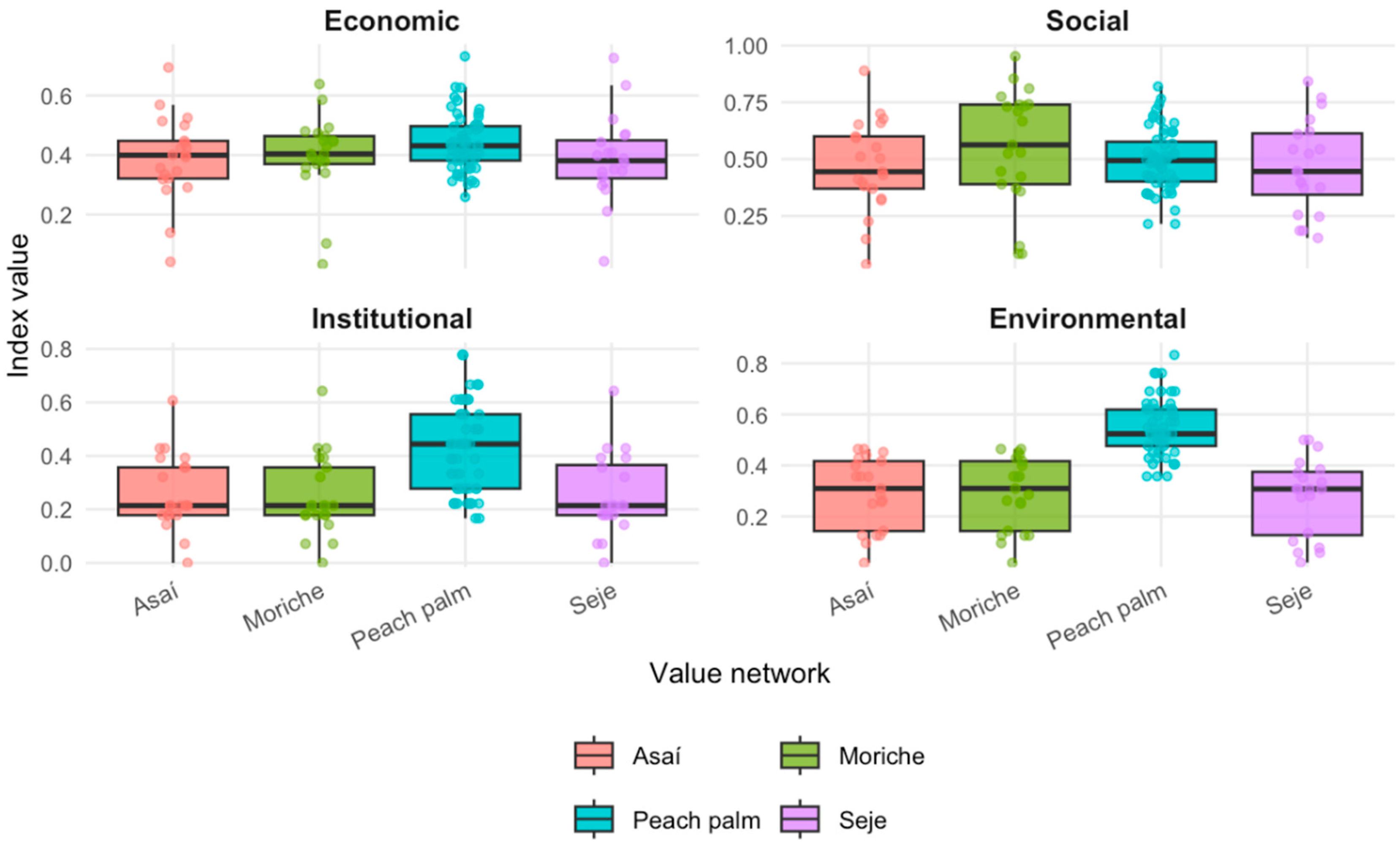

The estimation of the index reveals that the analyzed VNs exhibit low performance across all four dimensions, with scores not exceeding 1.9 (

Table 3). Peach palm (1.84) achieves the highest overall value, indicating that among the products assessed, it demonstrates the most balanced performance by adequately integrating the four dimensions. In contrast, Seje (1.44) and Asaí (1.44) obtained the lowest total scores, reflecting weaknesses primarily in the environmental and institutional dimensions, while Moriche (1.49) occupies an intermediate position, standing out for its performance in the social dimension.

3.1. Economic Dimension

In Guaviare, the fruiting calendar is staggered throughout the year. Asaí concentrates its harvest between March and June, when bunches ripen massively; afterwards, supply declines until the next season. Seje enters its harvest period around August–September, while Moriche follows in October–November; these are short and clearly defined windows. Peach palm, in contrast, presents two annual peaks—February and September—during which prices tend to fall due to increased supply.

For Asaí, harvesting involves climbing wild palms using harnesses, straps, and foot “maneas,” cutting only ripe bunches while avoiding tree damage; these are low-impact practices that replace older methods such as felling and include local variations (

pecoña, strobos, ramps) documented for the Colombian Amazon [

24]. In Seje, a similar scheme is used: trained climbers cut bunches under approved management plans and permits, with an emphasis on low-impact harvesting techniques. In Moriche, logistics depend on wetlands: access is usually by canoes or wading through shallow waters, after which climbers ascend tall palms to cut bunches. In many Amazonian regions, climbing has been promoted as a replacement for felling to conserve Morichales, a practice now extended through manuals and projects.

Peach palm—a cultivated species—is harvested in two ways: from the ground using long poles with hooks to detach bunches into cushioned receptacles, or by climbing with marotas (specialized climbers) to reduce fruit damage and grain loss. In both cases, careful handling is recommended to preserve fruit quality.

Across all four networks, harvesting is manual and selective. For NTFPs, it depends on climbers and management plans/licenses, whereas in the Peach palm, the cultivated nature of production allows for a mix of climbing and pole harvesting. Harvest windows are relatively stable, though rainfall and drought can shift or shorten them annually.

At the household level, economies are shaped by pluriactivity and seasonality. In Peach palm, Asaí, and Seje, livestock provides the income base, while fruit harvesting serves as a complementary, seasonal income flow dependent on fruit quality. In Moriche, the main income sources are trade, followed by livestock and other Amazonian fruits. This shared strategy—diversification to buffer seasonality—largely explains the income dispersion observed both across and within networks.

Integration across multiple value-chain stages emerges as the best factor explaining income ceilings. In the Peach palm, those engaged simultaneously in production, processing, and intermediation achieve significantly higher seasonal earnings compared to producers relying solely on primary fruit sales (around one monthly minimum wage), with peaks varying according to fruit volume and quality. In Asaí, Seje, and Moriche, associations that process fruits (pulps, flours, oils) also obtain improved outcomes, though on a more modest annual scale than the best cases of Peach palm. The general pattern is clear: greater integration correlates with greater value capture, with differences arising from effective demand and scale in each network.

Costs are concentrated in labor—highly specialized for climbing, pruning, thinning, harvesting, and sorting—alongside tools, transport, and processing. In the Peach palm, 80% of producers hire labor, production costs absorb about 40% of revenues, 29% have access to credit (mainly livestock-oriented), and savings are minimal, indicating financial fragility despite widespread land tenure that provides decision-making autonomy. In Asaí, labor hiring is also required, averaging 10 workdays per month during harvest; in Seje and Moriche, labor demand ranges from 5 to 10 workdays at about USD 11.8 per day. In all cases, family labor is insufficient and must be supplemented by hired labor for harvesting and processing. Additionally, all four networks face labor bottlenecks and significant logistical costs—especially poor road conditions—that increase fruit transportation expenses, ranging from USD 300 to USD 2075.

Commercialization is characterized by local and regional sales with limited formalization. Peach palm relies on itinerant intermediaries who set prices based on fruit quality. Some local buyers open routes toward San José del Guaviare, Villavicencio, and Bogotá cities, though without stable contracts. Asaí shows the clearest distribution pattern—60% local, 30% regional, and 10% national—yet only 5% report formal agreements. Seje and Moriche follow similar arrangements, with weaker demand in Seje. Where processing plants are managed by associations, value aggregation gains importance. Peach palm also exhibits a distinctive feature: basic processing into silage for livestock self-consumption or small-scale sales, with 20% advancing toward higher-value products.

In summary, the four networks share seasonality, reliance on specialized labor, and commercial instability. Vertical integration emerges as a key factor enhancing incomes (Peach palm, and to a lesser degree Asaí and Moriche), while financial robustness is uneven (Peach palm shows credit access largely external to the crop and limited savings). Improvement pathways converge on three fronts: formalizing commercial relationships, strengthening processing and logistical infrastructure, and reinvesting in productive capacities to buffer seasonality and more consistently capture value that currently dissipates through intermediaries.

3.2. Social Dimension

Comparing the social dimension across the VNs reveals diverse configurations of educational capacities, forms of association, access to training, and socio-political contexts.

Educational contrasts are evident. Peach palm occupies the most vulnerable position, with primary education predominating almost exclusively. Asaí and Seje display stronger educational bases, with about 40% holding university degrees (and an additional 30% with technical training in Seje). Moriche lies in an intermediate position, more evenly distributed among primary/secondary (35%), university (35%), and technical (30%) education. This suggests that while Peach palm faces severe human capital limitations, the other chains have greater academic diversity and preparation, enabling them to strengthen productive and organizational processes.

All VNs share a central feature in social organization: broad membership in associations and cooperatives. In the Peach palm, affiliation is highly homogeneous, largely concentrated in FENACHO, though other associations exist (Asochontarregua, Asofamilias, Asopagua, Asomujeres), but with weaker collective structures and lacking formal agreements. Asaí, Seje, and Moriche also rely on associative ecosystems (e.g., Asoprocegua, Asomeeret, Comagua, Comguaviare, Agroindustrias del Bosque), often with their own processing plants financed by development projects. In these VNs, associativity translates into stronger value aggregation and closer connections among producers, processors, and marketers.

Access to training shows internal inequalities. In the Peach palm, only 16% reported access to specialized training. In Asaí, there is a clear gap between actors integrated across multiple stages and those limited to harvesting; among the latter, 43% reported low participation in training spaces. Moriche stands out as the most strengthened network, with 80% reporting that they received training. More broadly, 54% of actors accessed training processes, particularly those linked to processing and commercialization, while harvest-focused actors participated less.

Politically and relationally, important similarities emerge. Peach palm is the only chain explicitly reporting pressure from illegal armed actors affecting commercialization. Asaí, Seje, and Moriche report this issue only marginally. These networks depend significantly on external projects and coordination with community institutions such as local action boards, particularly visible in Seje and Moriche. Organizational strength and institutional support are essential to overcome structural vulnerabilities.

Overall, Peach palm, Asaí, and Seje share greater similarities, while Moriche stands out as the most strengthened in education and training.

3.3. Institutional Dimension

For all networks, institutional support has been constructed through external cooperation, prioritizing training and associative strengthening over infrastructure, logistics, and incentives. Government programs and organizations such as the Amazon Institute of Scientific Research (SINCHI), the Foundation for Conservation and Sustainable Development (FCDS), and municipal and departmental administrations have promoted technical, organizational, and value-aggregation capacities. However, logistical bottlenecks (deficient road infrastructure) and gaps in incentives or compensation for sustainable forest management persist. This asymmetry—strong “soft” institutional support but limited “hard” infrastructure—builds practices and knowledge but fails to resolve transaction costs and commercial fragility.

Peach palm stands out for its dense civic and sectoral affiliation: all respondents are linked to FENACHO, 43% additionally participate in other associations, and 70% are integrated into local action boards. This network visibility—through fairs and festivals—creates territorial deliberation spaces but does not translate into solid internal governance for collective decision-making on investments, infrastructure use, or market strategies. In other words, affiliation and visibility exist, but effective governance is lacking.

In Asaí, Seje, and Moriche, the pattern is similar regarding capacity-building support and associative strengthening, with a key difference: Asaí associations report subsidies for processing plants and training in good practices, whereas 99% of harvesters receive no direct subsidies. Public policy influence is weak—only 5% in the Asaí report on leadership roles in policy arenas. Inter-association agreements exist but remain partial: sharing harvesting licenses and occasionally purchasing harvests among organizations. Perceptions indicate weak trust and limit relational capacity, a situation mirrored in Seje and Moriche, with no compensation for conservation reported.

The dominant similarities are clear: cooperation focused on production management capacities, weak influence in sectoral policies at the regional level, limited formalization of commercial agreements among associations, and absence of public infrastructure to anchor progress. Differences are also evident: Peach palm has the densest civic affiliation and community presence (via local boards) and the strongest symbolic visibility; Asaí has advanced further in associative infrastructure thanks to subsidies; Seje and Moriche share strengthened production management capacities but limited public goods and regulatory dependence through license concentration. The common challenge is moving from training to collective governance: diversifying licenses to avoid bottlenecks, formalizing inter-association rules (plant use, reference prices, purchases, traceability), and linking cooperation to public investment and stable market mechanisms that convert existing capacities into genuine negotiating power and sustainability.

3.4. Environmental Dimension

All networks operate under climatic variability. Droughts reduce fruit availability (Peach palm via water scarcity; Seje and Moriche via productivity declines; Asaí and Moriche also via phenological shifts). Torrential rains interrupt access and raise transportation costs, affecting processing and marketing through road damage. Respondents reported little to no adaptive action (no early warning systems, contingency plans, or preventive protocols).

A key similarity among Asaí, Seje, and Moriche is their wild origin: fruits are harvested manually and selectively by skilled climbers under licenses and management plans. This minimizes direct climate impacts on harvesting. Beyond climate, deforestation and weak institutional control exacerbate vulnerability, particularly for NTFPs that depend on forest ecosystems.

Peach palm, as a cultivated species, contrasts sharply. Its dominant vulnerability is water scarcity: producers must construct rainwater wells, while storms and heavy rains damage access roads. Soil management is empirical, based on training and technical assistance, but chemical inputs are used: 10% apply fertilizers without technical dosage. Unlike forest-based fruits, some ecological practices exist at the farm level, including waste management during processing; 9% reported crop rehabilitation after climatic or disease events. Thus, environmental performance is largely determined by individual producers, in contrast to forest-based systems.

Among NTFPs, subtle differences emerge. In Asaí, rainfall shifts ripening windows, while drought reduces yields and quality; compliance with regulations exists, and isolated restoration/recycling cases are reported, though conservation agreements are scarce. In Seje, drought has a greater impact (yield decline), and actors emphasize low-impact harvesting (climbing, canopy protection) and good manufacturing practices in processing, while sharing concerns about forest loss and weak influence. In Moriche, water is the defining factor: there is no harvest during droughts (wetland ecosystem), while heavy rain causes flooding, restricted access, and floral abortion. In all three, “good practices” discourse coexists with the absence of formal climate adaptation measures.

In summary, the four networks share the following: (i) high exposure to climatic extremes and limited adaptive responses; (ii) dependency on logistics (roads/access) as a key impact modulator; and (iii) governance gaps (absence of early warning systems, conservation agreements, and coordinated land management). Differences lie in the Peach palm, where pests, diseases, and farm-level management (chemical inputs, ecological practices, waste management) dominate, whereas Asaí, Seje, and Moriche face direct impacts on forest harvesting and deforestation threats. Moriche, due to its wetland ecology, is the most water-dependent: productivity collapses during drought, and access is cut off during floods.

3.5. Extended Results: Differences and Similarities

The comparative analysis of indicators shows differentiated profiles across the four networks, though with mostly convergent general trends (

Table 4).

3.5.1. Results by Dimension

Peach palm shows the strongest overall performance in the economic dimension, leading in income from processing (0.94), diversification of activities (0.92), and labor use (0.89). In contrast, Seje records the lowest value for income from sales (0.38). Asaí, Seje, and Moriche share identical scores for income derived from product transformation and diversification of activities (0.70), as well as similar values in labor investment, though they show low performance across most other indicators. The NTFPs present relatively similar profiles, without outstanding peaks. A common trait across all four networks is their weakness in innovation and climate response (≤0.14).

In the social dimension, Moriche scores highest in formal education (0.76), organizational participation (0.60), and participation in events addressing climate-related challenges (0.33), configuring the strongest social foundation. Peach palm shows the lowest score in formal education level (0.20), but leads in training related to value networks (0.81) and in the perception of being unaffected by public order issues (0.90). Asaí, Seje, and Moriche occupy similar positions in variables such as organizational participation (0.58–0.60), access to basic services (0.54–0.55), and technical knowledge of value-chain stages (0.52–0.55).

In the institutional dimension, Peach palm achieves the highest values in institutional training (0.53), road infrastructure (0.56), and collaborative agreements (0.55), suggesting a relatively more favorable institutional environment. Asaí, Seje, and Moriche show low and comparable results (0.41–0.04). Low levels of financial support are consistent across all networks (0.28–0.04), with Seje and Moriche presenting the lowest values.

Finally, in the environmental dimension, Peach palm demonstrates the strongest results, with access to water sources (0.89), favorable perceptions of stable forest areas, and assessments of on-farm forest conditions (0.70). Asaí, Seje, and Moriche show similar values across most variables, except for Moriche in its perception of increased forest areas. In all cases, there is an absence of climate-change subsidies and a lack of environmental strategies. These findings reflect, on the one hand, that actors in the Peach palm network reported not having used forest areas for production in the last five years, relying instead on former grazing lands, and, on the other hand, that forest use restrictions have helped maintain more favorable perceptions of forest conditions.

Differences across VNs, as reflected in the index, are illustrated in

Figure 2. The results confirm that the Peach palm exhibits distinctive profiles compared to NTFPs harvested from forests. Environmentally, the Peach palm stands apart because its actors manage forest conditions more directly by owning their properties, unlike Asaí, Seje, and Moriche, which face constraints from deforestation threats that disrupt harvesting areas. Institutionally, heterogeneity in Peach palm is explained by divergent experiences with associative support: while some actors receive technical assistance and financial support, others operate individually with limited access to benefits.

3.5.2. Social Network Analysis

Social network analysis (SNA) complements the findings derived from the multidimensional index. While the index quantifies how well each network performs, SNA explains how such performance emerges—or is constrained—through the relationships among actors. In this analysis, “centrality” refers to the relative importance or influence of an actor within the network. For example, betweenness centrality describes actors who function as strategic intermediaries—those who connect otherwise separate groups and therefore facilitate or constrain information flows. Likewise, “density” denotes how interconnected the network is overall; a high-density network reflects many direct ties among actors, suggesting frequent interactions and stronger collective coordination, whereas low density indicates fewer connections and potentially weaker collaboration.

The results allowed us to identify different types of interactions among stakeholders that shape the studied VNs, as well as the flows connecting them across production, processing, and commercialization stages. The networks exhibit moderate density and centrality, with associations and cooperatives emerging as key nodes for coordination, investment access, and market linkages.

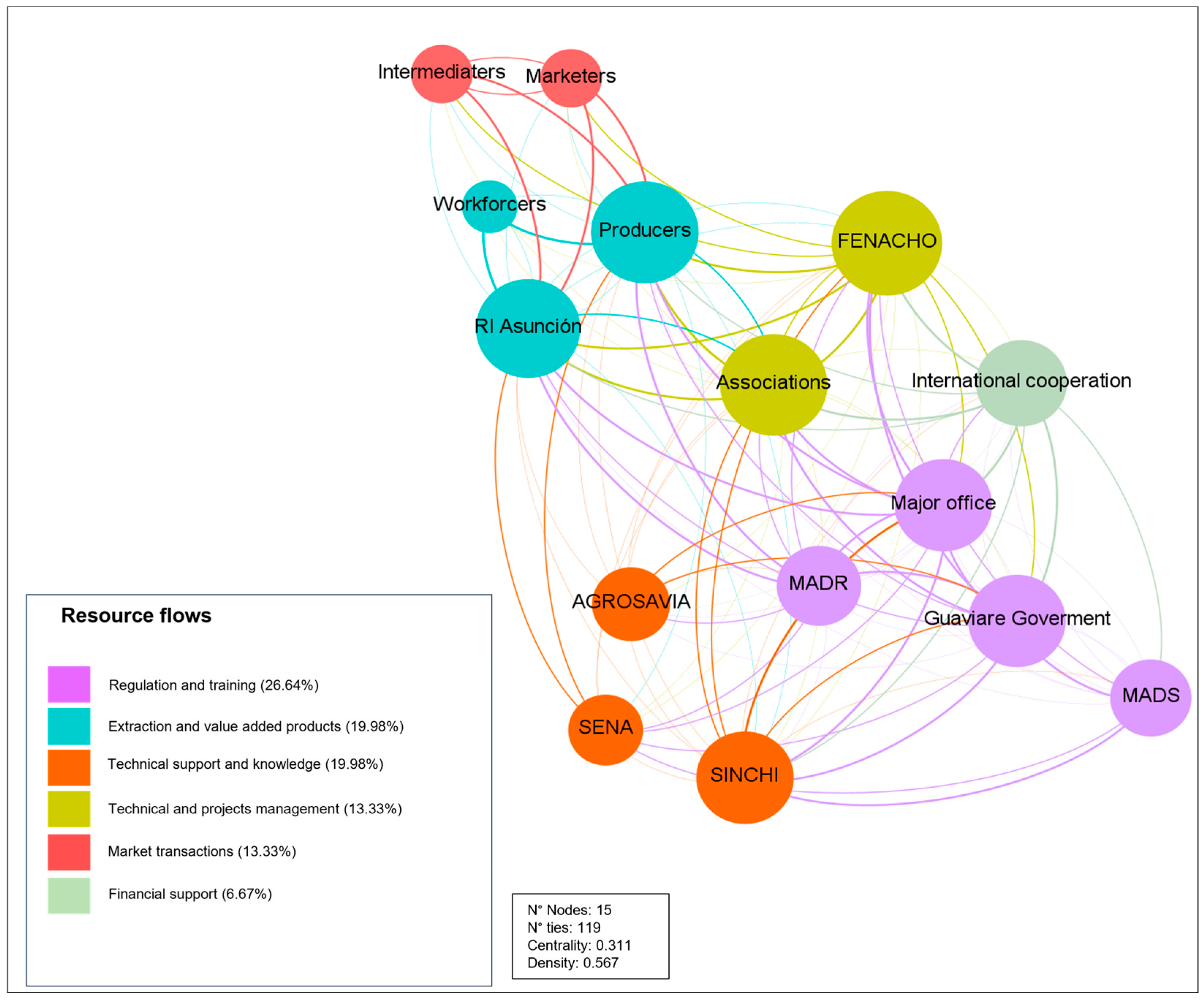

3.5.3. Peach Palm

The Peach palm network comprises 15 actors and 119 ties, with medium density. The most connected nodes are government entities and local associations. The structure is organized into three clusters: (i) the productive–commercial cluster—producers, labor, intermediaries, traders, and the La Asunción Indigenous Reserve—where raw materials, labor, and price formation flows occur; (ii) the associative cluster, led by FENACHO and local associations, acting as a hinge between the productive base and the broader system; and (iii) the institutional–technical cluster, composed of SINCHI, AGROSAVIA, SENA, departmental and municipal governments, MADR, MADS, and international cooperation agencies. NGOs and public entities connect densely with the associative block, channeling training, technical assistance, and visibility primarily through FENACHO/associations rather than directly to the market or individual producers (

Figure 3).

Centrality metrics highlight three nodes with complementary functions: producers (high degree centrality) as the operational core linking most actors; FENACHO (high betweenness centrality) as the organizational broker and project manager articulating decisions and resources; and SINCHI as a knowledge node with strong institutional influence. Cooperation is relatively well distributed, with no single actor monopolizing interactions, and the network depends on bridging nodes for the circulation of information, support, and coordination.

A weakness emerges at the commercial–state interface: Market nodes (intermediaries and traders) have weak connections with governmental and technical actors, resulting in commercialization marked by low formalization (contracts, standards, traceability) and volatile pricing. In parallel, MADR appears peripheral, providing guidelines and production projects with limited operational impact on daily flows. Consequently, the network advances through effective “soft” institutional mechanisms (training, associative coordination, fairs) but lacks the “hard” anchoring needed to stabilize rules and transactions.

Three strategic lines of action emerge to strengthen this value network: (1) reinforcing the market–state bridge through framework contracts, quality and traceability protocols, and public procurement linked to cooperatives; (2) diversifying bridging nodes (e.g., inter-association platforms, rotating leadership roles) to mitigate bottleneck risks concentrated in FENACHO; and (3) consolidating regulatory and environmental anchoring (a single-window system with harvest-aligned timelines, field monitoring, and verification). Together, these measures could transform the network’s current connectivity into lower transaction costs, stronger bargaining power, and greater resilience.

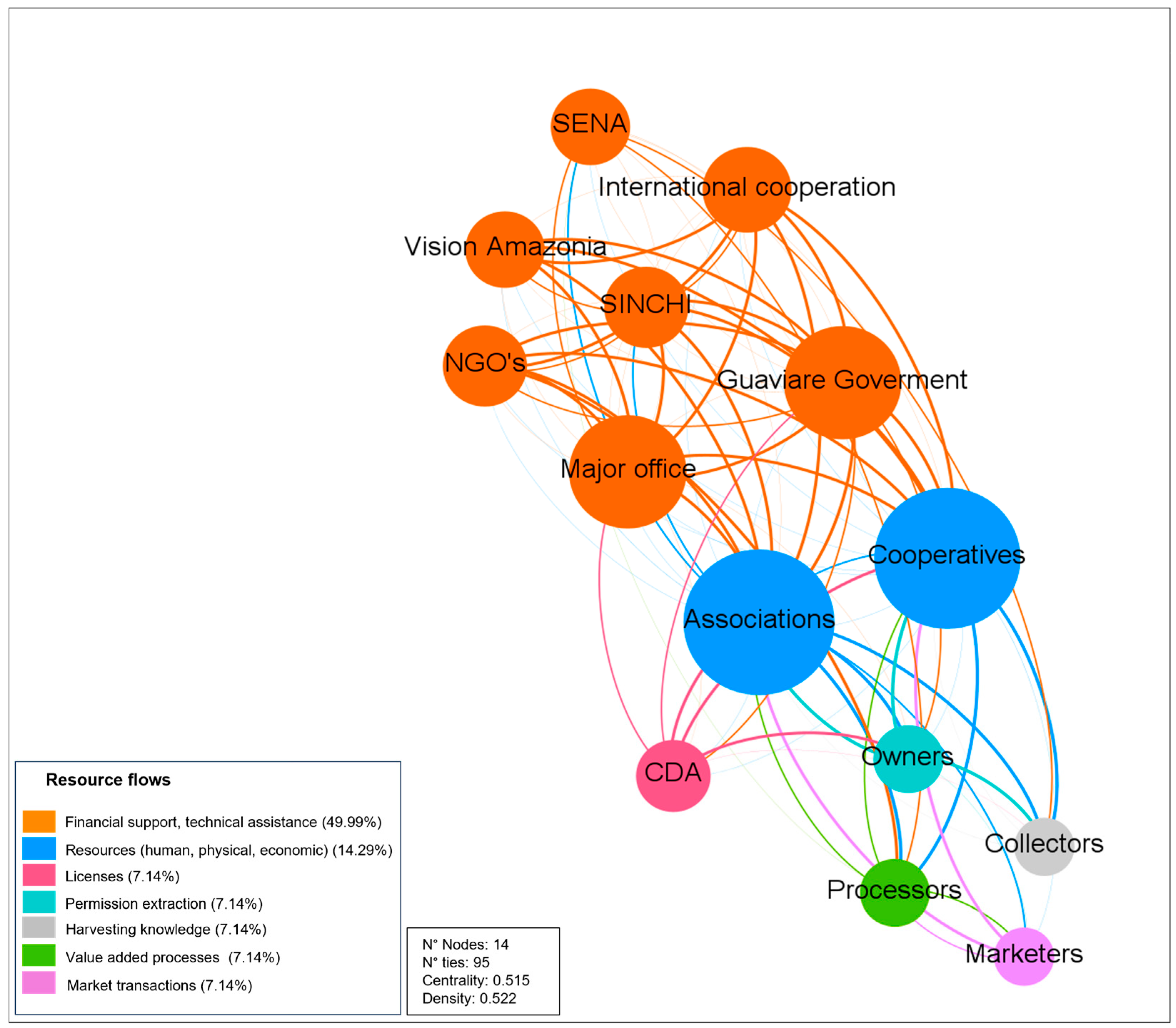

3.5.4. Non-Timber Forest Products (Asaí, Seje, Moriche)

No major differences were identified in the network typologies and relationships of the non-timber forest products (NTFPs). In general, the network exhibits a core–periphery structure articulated by two macro-modules that converge at the center through cooperatives and associations, which function as the most central nodes. In the upper quadrant, the institutional–technical block—including the Guaviare Government, Major Office, SINCHI, SENA, Visión Amazonia, NGOs, and international cooperation—displays high internal density and strong ties with grassroots organizations. In the lower-right quadrant, the productive–commercial block—comprising owners, collectors, processors, and marketers—connects with the institutional block almost exclusively through associations and cooperatives. The Corporation for the Sustainable Development of Northern and Eastern Amazonia (CDA) appears peripheral, indicating low regulatory centrality in everyday flows (permits/monitoring) (

Figure 4).

Functionally, associations and cooperatives act as intermediaries bridging structural gaps between the state/cooperation sphere and the operational stages of the chain. Through them, they circulate resources such as technical assistance, training, product transformation, and marketing strategies. The centrality of SINCHI and the departmental government suggests strong anchoring in development, research, technology, and public coordination. However, these ties do not extend directly to marketers or processors, evidencing that market nodes maintain few direct connections with the state–technical block, a symptom of weak commercialization formalization. The lateral position of CDA reinforces the interpretation of proceduralist environmental regulation—focused on licenses and management plans—as a regulatory actor, but with very low capacity to relate to the total node of the network, which effectively makes it a non-central actor, although this result is surprising in a value network that depends on the license to make use of the resource. This limits its operational impact on technical assistance and the sustainability of forest management, primarily due to a lack of institutional coordination.

This network structure highlights both a strength—a cooperative “backbone” sustaining capacity-building and external cooperation—and a systemic risk of over-centralization, whereby coordination depends on a few bridging nodes; if these fail, the network risks fragmentation. The implications for system performance are clear: (i) economically, value capture is limited by the weak market–state interface; (ii) institutionally, “soft” institutional frameworks (training and agreements) prevail without the “hard” anchors needed to stabilize transactions; and (iii) environmentally, the regulator’s low centrality undermines the translation of permits into conservation outcomes.

To strengthen the network without increasing coordination costs, the graph suggests three strategic actions: (1) building direct bridges between marketers/processors and government–SINCHI–SENA (framework contracts, quality standards, traceability mechanisms); (2) diversifying bridging nodes through an inter-associative platform to reduce bottlenecks; and (3) repositioning CDA as a single-window authority with permitting schedules aligned to seasonal cycles and field-based verification mechanisms. In this way, the network could transform its strong associative connectivity into price stability, reduce operational risk, and increase resilience.

4. Discussion

Our results demonstrate that all VNs exhibit deficiencies across the dimensions analyzed. None achieves optimal performance; nevertheless, these findings are crucial for generating recommendations for network actors as well as for guiding institutional programs and projects. Understanding VNs through indicators, dimensions, and social network analysis can help researchers working on emerging agricultural value chains worldwide to identify fundamental aspects of their functioning and highlight key elements for strengthening performance and sustainability.

The analysis of non-timber forest products (NTFPs) reveals similar patterns across all dimensions, largely because the same actors participate in multiple stages of these VNs. However, Moriche shows greater heterogeneity in the social dimension, since some actors are not involved in the Asaí and Seje networks nor in their respective stages. Indicators confirm the need for technical planning and institutional supervision within a formal regulatory framework. This involves obtaining permits from the competent environmental authority, which requires the preparation of a management and harvesting plan. For many community associations, however, this process has become an administrative burden that discourages compliance due to bureaucratic complexity and associated costs.

The low environmental scores are symptomatic of the historical pressures of the agricultural frontier and the institutional incapacity to effectively promote sustainable land use models. This places NTFPs in a position where immediate economic survival (area expansion) clashes with conservation objectives. Furthermore, associations do not own the forest lands, forcing them to intermediate between environmental authorities, landowners, collectors, and other associations, which has led to fragmentation in relationships—a factor that continues to be highlighted in studies such as that of Guariguata et al. [

39]. This particularity disincentivizes the continuity of sustainable forest utilization.

Consequently, this is characterized by a limited and fragmented institutional presence outside urban centers, which complicates the application of regulations, the enforcement of oversight, and the provision of essential public services such as financing, technical assistance, and infrastructure. Therefore, this institutional void compels value networks to rely on mechanisms of relational governance—based on trust and informal cooperation—to function. While these arrangements can be locally effective, they prove insufficient when organizations are required to interact with external markets or larger-scale institutions. Furthermore, development and conservation policies often operate in isolation. The lack of coordination between environmental authorities (e.g., CDA), agrarian agencies, and local governments generates contradictory regulations or an incoherent supply of support for NTFP collectors, thereby deepening the structural barriers to sustainability.

Peach palm, while comparatively better positioned in institutional and environmental dimensions, displays greater heterogeneity in institutional performance. Unlike NTFPs, its access to self-managed resources has fostered more adaptive and transformative dynamics, consistent with findings by [

40] regarding larger, more heterogeneous networks. Environmentally, Peach palm actors differ from NTFPs by exercising direct decision-making over conservation strategies within their own properties. Nevertheless, production remains incipiently mechanized: most farmers cultivate under monoculture systems, with limited knowledge of soil and pest management. Similarly, product transformation processes lack innovation, technology, and standardized techniques for quality control. Collective responses are weak, as clear collaboration agreements are largely absent.

The main challenges remain in product transformation and the generation of value-added subproducts, but these require greater investment in logistics, transportation, storage, innovation, and technology [

41].

Although institutional support has contributed to positioning products and stimulating their social and economic dimensions, significant weaknesses persist in organizational capacity, associative structures, and the ability of directly involved actors to respond to emerging challenges that threaten long-term stability.

Across the four networks, our findings highlight four critical aspects:

Historical and emerging roles of NTFPs. Although exotic and native fruits have historically sustained rural livelihoods globally [

41], their use in Guaviare was traditionally restricted to subsistence among Indigenous communities. At present, however, they are gaining prominence through tourism and gastronomy. Similar experiences have been documented in India, where exotic fruit production and commercialization significantly increased smallholder incomes [

5,

9,

27]. However, Ruben [

13] argues that their impact on livelihoods remains limited and has not triggered substantive market transformations, despite novel approaches that integrate social and ecological valuation. This also depends on the market demand for these products and their importance in sustaining the livelihoods of the actors involved in these VNs, as conflicts over use and commercial value may arise—issues that have been highlighted in studies such as Herrero-Jáuregui et al. [

42].

Low adoption of technology and innovation. Despite interest in training, the adoption of technical practices and innovations for value addition remains low. In the Peach palm network, for example, most producers disagree on the technical requirements of cultivation and struggle to improve techniques for developing quality subproducts. Similar challenges have been reported in the value chains of fruits, medicinal plants, and wheat [

1,

30,

39,

42].

Weak social cohesion. Although associations and participatory spaces exist, largely promoted by projects and individual leaders, cooperation among producers, processors, and marketers is limited. This aligns with [

14], who found that the success and sustainability of agricultural VNs depend primarily on cooperative culture. Ricciotti [

27] also highlights that long-term sustainability requires membership in networks of enterprises, associations, or guilds bound by complementary roles and trust. In their absence, small producers face severe external restrictions that undermine operational viability, alongside recurrent challenges in logistics, infrastructure, institutional support, and coordination [

12].

Low political incidence. Actors in these networks rarely extend their influence beyond receiving institutional benefits, maintaining weak bargaining power to negotiate agreements on production, commercialization, and incentives. Without stronger political engagement, these initiatives risk remaining short-lived, as evidenced by community forest management in Petén, Guatemala, where political incidence was key to both commercial and conservation success [

43,

44].

The combined results of the social network analysis and the multidimensional index reveal that the performance of the Amazonian fruit value networks is closely linked to their structural configuration. The networks characterized by low density and limited betweenness centrality—where only a few actors serve as intermediaries—tend to exhibit lower scores in the institutional and environmental dimensions of the index. This structural fragmentation restricts information exchange, reduces coordination, and weakens collective responses to market and climatic pressures. Conversely, networks with more cohesive structures, where interactions are more evenly distributed, and intermediaries facilitate cross-group linkages, align with higher performance in the adaptive and economic dimensions. These findings suggest that network structure does not merely reflect existing relationships but actively shapes the capacity of actors to manage risks, mobilize resources, and sustain value generation across the chain. Strengthening connectivity and fostering more distributed forms of centrality could therefore enhance the overall resilience and functioning of these value networks.

Finally, social network analysis underscores the role of associations as central nodes for coordination, investment access, and market linkages. It also clarifies which nodes require network consolidation and which require reinforcement. Such analyses can inform the construction of more robust networks [

45]. At the same time, they reveal governance gaps, economic dependence on associations, and shortages of skilled labor for fruit harvesting [

5,

9,

10,

46]. Without strengthening these networks, these “novel foods” may fall under the control of retailers and agro-industrial firms [

47,

48,

49].

The analyzed networks should be consolidated as viable alternatives that simultaneously increase rural incomes and generate incentives for conservation. Many structural limitations, however, cannot be overcome by voluntary action alone, and fundamental changes in governance, market organization, and regulatory oversight are required.

To address the institutional and market weaknesses identified in these value networks, several policy actions are both necessary and feasible. First, reducing institutional fragmentation requires the creation of a coordinated governance platform that brings together environmental authorities, producer associations, municipal institutions, and NGOs to harmonize regulations and streamline support mechanisms. Strengthening organizational capacity within associations is also essential; targeted training in administrative management, commercialization, and legal compliance would enhance their ability to negotiate, manage resources, and maintain sustainable harvesting practices, particularly given their limited control over the lands where extraction occurs. In parallel, simplifying and standardizing the regulatory framework for non-timber forest products would lower transaction costs and reduce the legal uncertainty that currently deters formal market engagement. Improving rural connectivity—especially road infrastructure and local collection and storage facilities—would directly mitigate logistical constraints that limit market access. Finally, fostering formal and sustainable market channels through traceability systems, contract arrangements with buyers, and integration into public procurement programs would help to stabilize demand and reward sustainable practices [

49]. Collectively, these measures can be expected to reinforce institutional support, strengthen market formalization, and enhance the resilience and performance of Amazonian fruit value networks in Guaviare.