Comparison of Genomic Variation and Population Structure of Latvian Dark-Head with Other Breeds in Latvia Using Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Animals

2.2. DNA Extraction and Genotyping

2.3. Genomic Variation Analysis

2.4. Genetic Population Structure Analysis

3. Results

3.1. SNP Statistics and Genetic Diversity

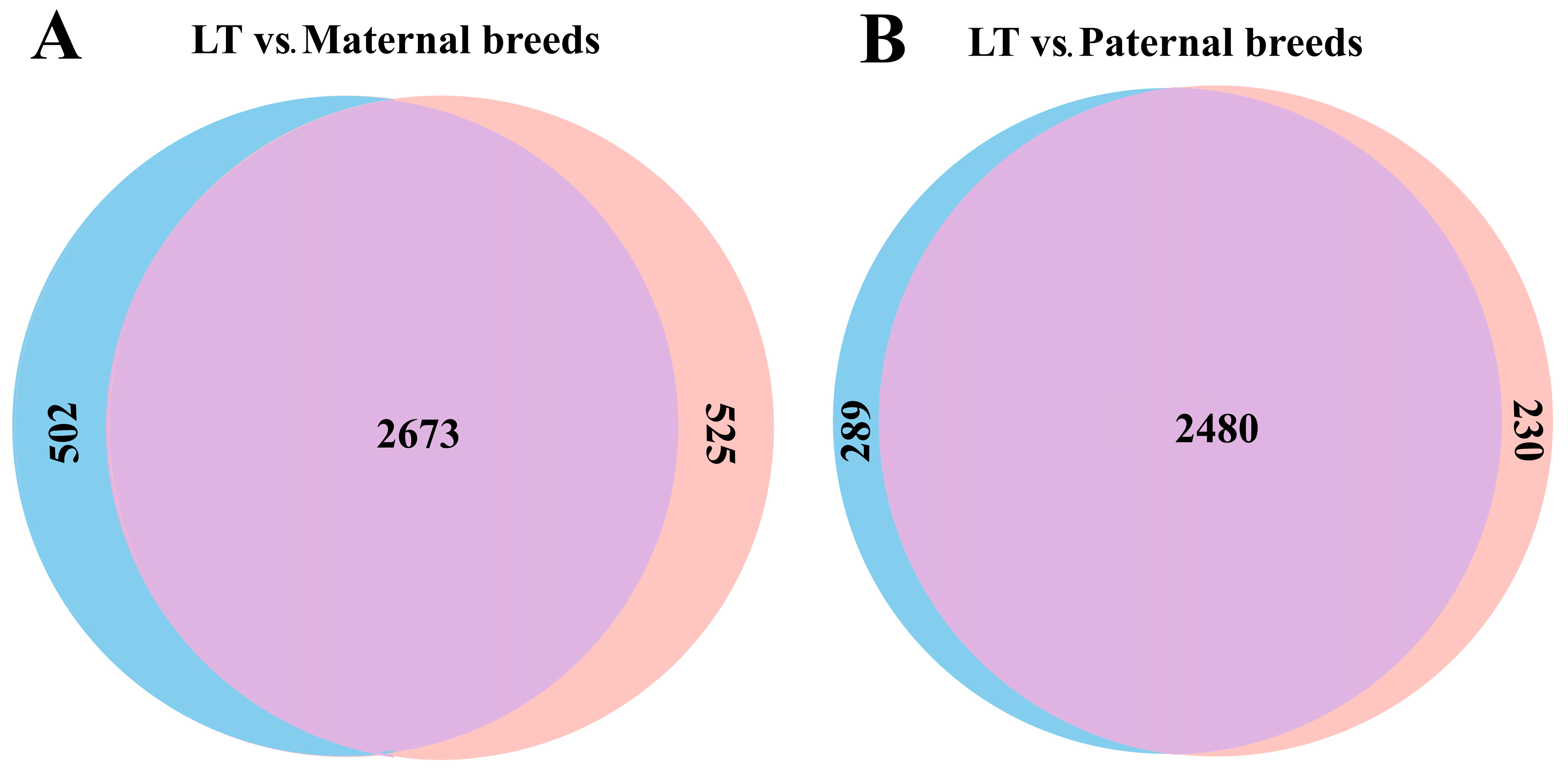

- Comparative fixed SNP analysis

3.2. Genetic Population Structure

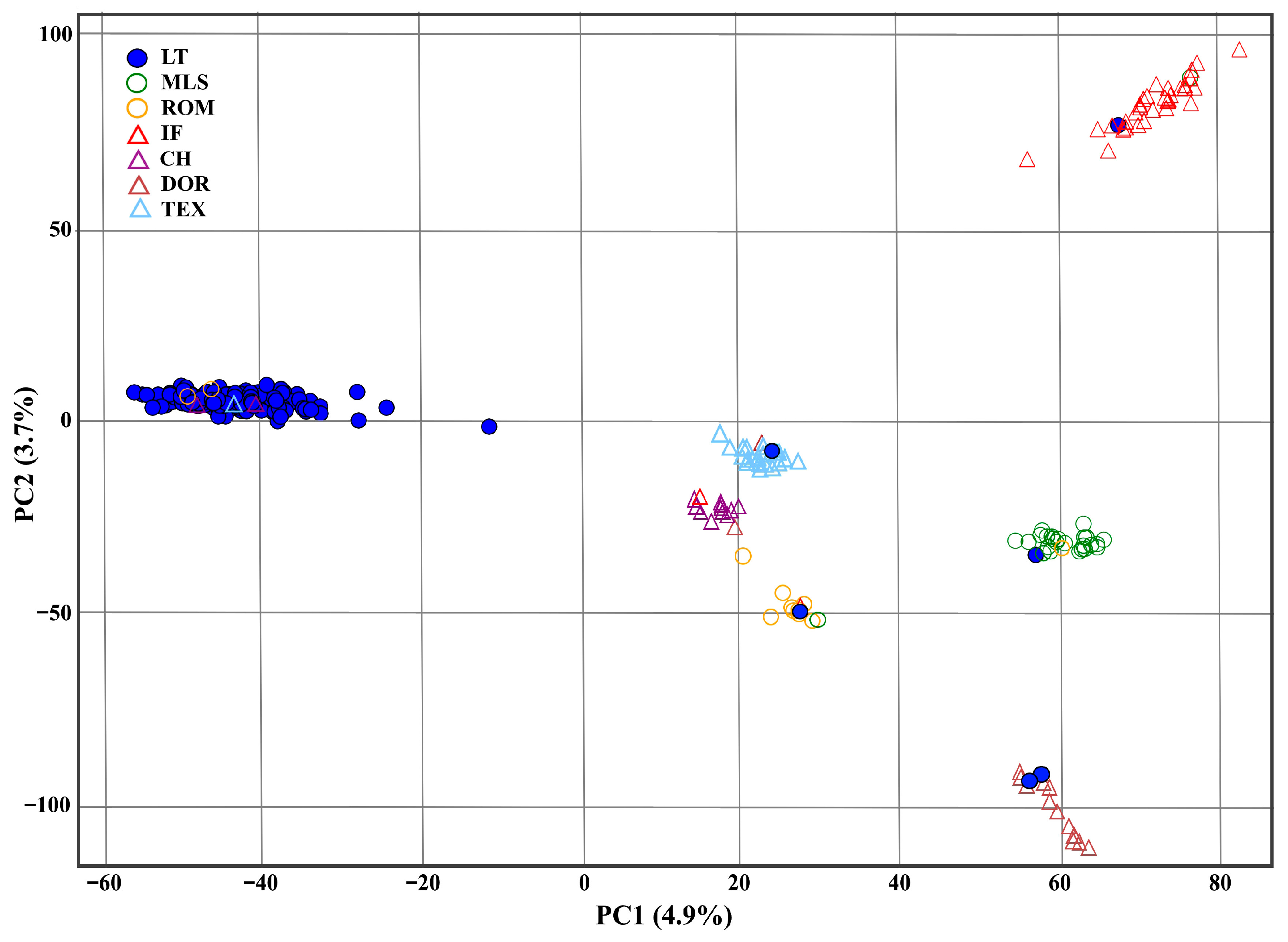

- Principal component analysis (PCA)

- Genetic differentiation (FST)

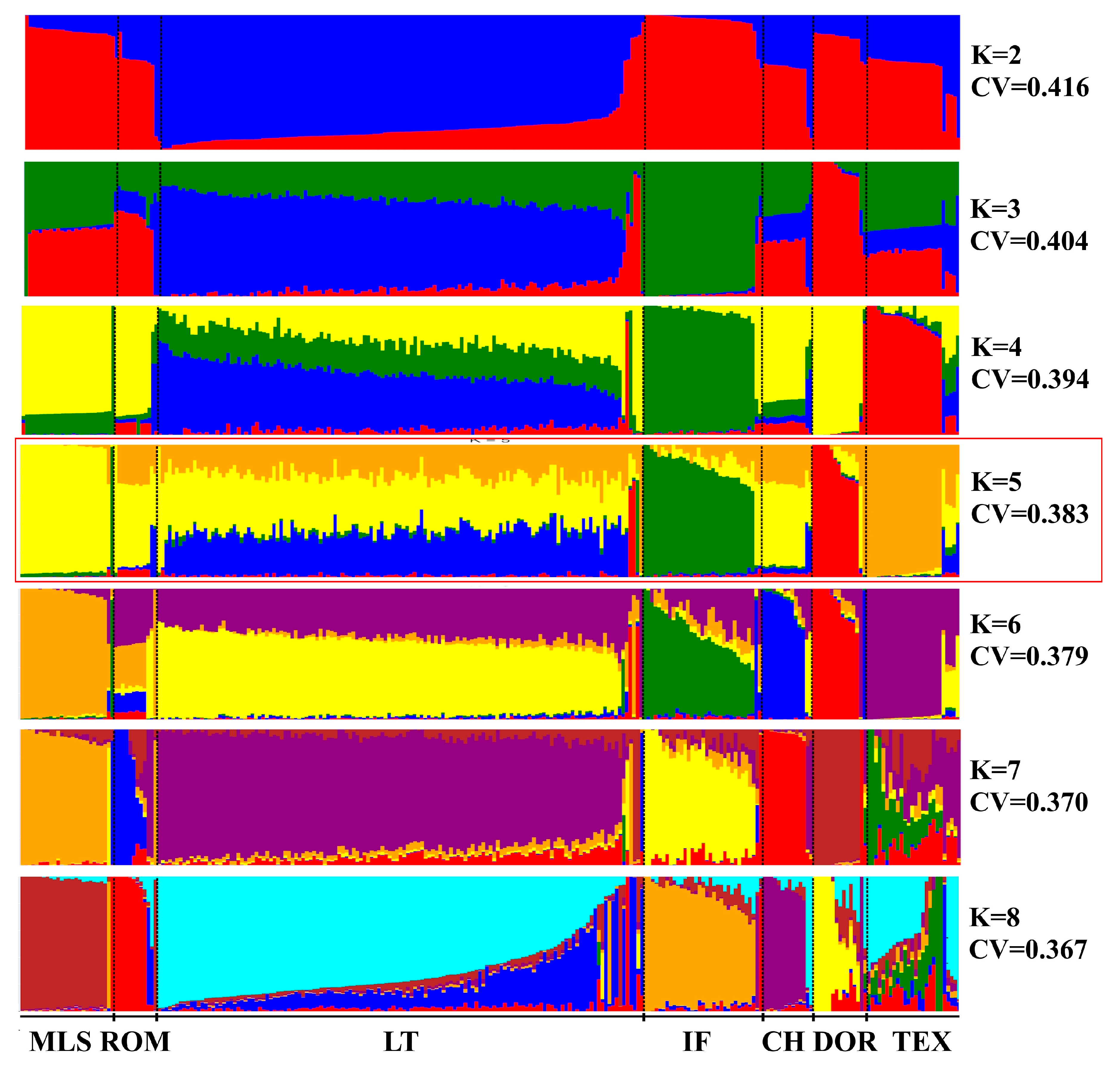

- Admixture analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mazinani, M.; Rude, B. Population, world production and quality of sheep and goat products. Am. J. Anim. Vet. Sci. 2020, 15, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudra, D.; Valdovska, A.; Kairisa, D.; Galina, D.; Jonkus, D.; Ustinova, M.; Viksne, K.; Kalnina, I.; Fridmanis, D. Genomic diversity of the locally developed Latvian Darkheaded sheep breed. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IWTO. About Sheep. 2022. Available online: https://iwto.org/sheep-wool/ (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Kawęcka, A.; Gurgul, A.; Miksza-Cybulska, A. The Use of SNP Microarrays for Biodiversity Studies of Sheep—A Review. Ann. Anim. Sci. 2016, 16, 975–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LAAA (Latvian Sheep Breeders Association). Sheep Breeds. [Description of form in Latvian]. 2025. Available online: https://www.laaa.lv/lv/skirnes-saimniecibas/aitu-skirnes/ (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- LRSS. Data from the Latvian Rural Support Service (Latvijas Lauku Atbalsta Dienesta Dati). 2025. Available online: https://registri.ldc.gov.lv (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- LAAA (Latvian Sheep Breeders Association). Genealogy Programs. [Description of form in Latvian]. 2025. Available online: https://www.laaa.lv/lv/skirnes-saimniecibas/ciltsdarbaprogrammas/ (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Justice, S.M.; Jesch, E.; Duckett, S.K. Effects of Dam and Sire Breeds on Lamb Carcass Quality and Composition in Pasture-Based Systems. Animals 2023, 13, 3560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tampaki, M.; Koutouzidou, G.; Melfou, K.; Ragkos, A.; Giantsis, I.A. The Importance of Indigenous Ruminant Breeds for Preserving Genetic Diversity and the Risk of Extinction Due to Crossbreeding—A Case Study in an Intensified Livestock Area in Western Macedonia, Greece. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanvanhossou, S.F.U.; Yin, T.; Gorjanc, G.; König, S. Evaluation of crossbreeding strategies for improved adaptation and productivity in African smallholder cattle farms. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2025, 57, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecvagars, J.; Kairiša, D. Sheep population structure of Latvia darkhead breed. In Proceedings of the Scientific and Practical Conference “Līdzsvarotā Lauksaimniecība”, Jelgava, Latvia, 22 February 2018; pp. 64–68. (In Latvian). [Google Scholar]

- Jonkus, D.; Paura, L. Analysis of genetic diversity in Latvian Darkheaded sheep population. Small Rumin. Res. 2025, 242, 107403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LAAA. Latvian Dark-Head Breed. [Description of form in Latvian]. 2025. Available online: https://www.laaa.lv/data/uploads/skirnu_apraksti/Latvijas_tumsgalve.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Bārzdiņa, D.; Kairiša, D. The production and quality analysis of Latvian darkhead breed lambs. Nordic View to Sustainable Rural Revelopment. In Proceedings of the 25th NIF Congress, Riga, Latvia, 16–18 June 2015; pp. 361–366. [Google Scholar]

- Ciani, E.; Crepaldi, P.; Nicoloso, L.; Lasagna, E.; Sarti, F.M.; Moioli, B.; Napolitano, F.; Carta, A.; Usai, G.; D’Andrea, M.; et al. Genome-wide analysis of Italian sheep diversity reveals a strong geographic pattern and cryptic relationships between breeds. Anim. Genet. 2013, 45, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, A.; Goldberg, V.; Navajas, E.; Iriarte, W.; Gimeno, D.; Aguilar, I.; Medrano, J.F.; Rincon, G.; Ciappesoni, G. Genomic variation and population structure detected by single nucleotide polymorphism arrays in Corriedale, Merino and Creole sheep. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2014, 37, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, C.; Tuersuntuohe, M.; Liu, S. Population structure and selective signature of sheep around Tarim Basin. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 11, 28133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapina, I.; Plavina, S.; Krasņevska, N.; Paramonovs, J.; Kairisa, D.; Paramonova, N. MSTN gene polymorphisms are associated with the feed efficiency of fattened lambs in Latvian sheep breeds. Agron. Res. 2024, 22, 1324–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapina, I.; Plavina, S.; Krasņevska, N.; Paramonovs, J.; Kairisa, D.; Paramonova, N. IGF1 and IGF2 gene polymorphisms are associated with the feed efficiency of fattened lambs in Latvian sheep breeds. Agron. Res. 2024, 22, 1001–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapina, I.; Kairisa, D.; Plavina, S.; Krasnevska, N.; Paramonovs, J.; Senfelde, L.; Paramonova, N. The Multi-Loci Genotypes of the Myostatin Gene Associated with Growth Indicators of Intensively Fattened Lambs of Latvian Sheep. Animals 2024, 14, 3143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, S.; Purcell, S.; Neale, B.; Todd-Brown, K.; Thomas, L.; Ferreira, M.A.R.; Bender, D.; Maller, J.; Sklar, P.; de Bakker, P.I.W.; et al. Plink: A tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 81, 559–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, D.H.; Novembre, J.; Lange, K. Fast model-based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Res 2009, 19, 1655–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weir, B.S.; Cockerham, C.C. Estimating F-Statistics for the Analysis of Population Structure. Evolution 1984, 38, 1358–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freking, B.; Leymaster, K. Evaluation of Dorset, Finnsheep, Romanov, Texel, and Montadale breeds of sheep: IV. survival, growth, and carcass traits of F1 lambs. J. Anim. Sci. 2004, 82, 3144–3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlahek, I.; Sušić, V.; Maurić, M.; Piplica, A.; Šavorić, J.; Faraguna, S.; Kabalin, H. Non-genetic factors affecting litter size, age at first lambing and lambing interval of romanov sheep in Croatia. Vet. Stanica 2022, 54, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chessari, G.; Criscione, A.; Tolone, M.; Bordonaro, S.; Rizzuto, I.; Riggio, S.; Macaluso, V.; Moscarelli, A.; Portolano, B.; Sardina, M.T.; et al. High-density SNP markers elucidate the genetic divergence and population structure of Noticiana sheep breed in the Mediterranean context. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1127354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurgul, A.; Jasielczuk, I.; Miksza-Cybulska, A.; Kawęcka, A.; Szmatoła, T.; Krupiński, J. Evaluation of genetic differentiation and genome-wide selection signatures in Polish local sheep breeds. Livest. Sci. 2021, 251, 104635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sveistiene, R.; Tapio, M. SNPs in Sheep: Characterization of Lithuanian Sheep Populations. Animals 2021, 11, 2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Salehian-Dehkordi, H.; Suo, L.; Lv, F. Impacts of Population Size and Domestication Process on Genetic Diversity and Genetic Load in Genus Ovis. Genes 2023, 14, 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKenzie, G.W.; Abbott, J.; Zhou, H.; Fang, Q.; Merrick, N.; Forrest, R.H.; Sedcole, J.R.; Hickford, J.G. Genetic diversity of selected genes that are potentially economically important in feral sheep of New Zealand. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2010, 42, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosrati, M.; Asadollahpour Nanaei, H.; Javanmard, A.; Esmailizadeh, A. The pattern of runs of homozygosity and genomic inbreeding in world-wide sheep populations. Genomics 2021, 113, 1407–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purfield, D.C.; McParland, S.; Wall, E.; Berry, D.P. The distribution of runs of homozygosity and selection signatures in six commercial meat sheep breeds. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Breed | Abbreviation | Breed Type | Sample | Sample in Breed Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LT | Latvian Dark-head | Maternal | 135 | 135 |

| MLS | Merinolandschaf | Maternal | 26 | 38 |

| ROM | Romanova | 12 | ||

| IF | Île-de-France | Paternal | 33 | 88 |

| CH | Charollais | 14 | ||

| DOR | Dorper | 15 | ||

| TEX | Texel | 22 | ||

| OX * | Oxford Down | 4 |

| Breed/Group | Ho | He | avMAF | SNP (n (%)) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not Minor | H-Poly | Fixed | Rare | |||||

| All samples | 0.35 | 0.39 | 0.32 | 24,875 (50.78) | 31,098 (63.49) | 2361 (4.82) | 2771 (5.66) | |

| LT | All | 0.36 | 0.37 | 0.30 | 24,830 (50.69) | 27,561 (56.27) | 2668 (5.45) | 3169 (6.47) |

| Resampling * | 0.36 [0.36–0.37] | 0.37 [0.36–0.37] | 0.29 [0.28–0.29] | 24,002 (49.00) [23,497–24,292] | 27,723 (56.60) [26,911–28,714] | 3709 (7.57) [3404–3965] | 3709 (7.57) [3404–3965] | |

| Maternal-type breed | 0.35 | 0.37 | 0.29 | 24,527 (50.07) | 26,677 (54.46) | 3198 (6.53) | 3198 (6.53) | |

| MLS | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.27 | 24,535 (50.09) | 23,581 (48.14) | 3936 (8.04) | 3936 (8.04) | |

| ROM | 0.35 | 0.33 | 0.25 | 23,221 (47.41) | 18,052 (36.86) | 4696 (9.59) | 4696 (9.59) | |

| Paternal-type breed | 0.34 | 0.39 | 0.31 | 24,653 (50.33) | 29,717 (60.67) | 2710 (5.53) | 2945 (6.01) | |

| IF | 0.34 | 0.34 | 0.26 | 24,407 (49.83) | 23,004 (46.97) | 4075 (8.32) | 4075 (8.32) | |

| CH | 0.33 | 0.32 | 0.24 | 23,962 (48.92) | 18,859 (38.50) | 5203 (10.62) | 5203 (10.62) | |

| DOR | 0.31 | 0.32 | 0.24 | 24,020 (49.04) | 20,066 (40.97) | 4902 (10.01) | 4902 (10.01) | |

| TEX | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.25 | 24,120 (49.24) | 20,206 (41.25) | 4755 (9.71) | 4755 (9.71) | |

| Breed/Group | Fixed SNP (n) | Comparing LT vs. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unique in LT (n (% from LT SNP)) | Common (n) | Unique in Breed (n (% from Breed SNP)) | ||

| LT * | 3709 [3404–3965] | - | - | - |

| Maternal-type breed: | 3198 | 502 (15.81 ^) [349–679] | 2673 [2622–2722] | 525 (16.42) [476–576] |

| MLS | 3936 | 812 (21.89) [555–1030] | 2893 [2821–2948] | 1043 (26.50) [988–1115] |

| ROM | 4696 | 612 (16.50) [384–805] | 3093 [2989–3174] | 1603 (34.14) [1522–1707] |

| Paternal-type breed: | 2710 | 289 (10.44) [287–296] | 2480 [2473–2489] | 230 (8.49) [221–237] |

| IF | 4075 | 720 (19.41) [489–924] | 2986 [2898–3056] | 1089 (26.72) [1019–1177] |

| CH | 5203 | 505 (13.62) [337–661] | 3200 [3057–3314] | 2003 (38.50) [1889–2146] |

| DOR | 4902 | 706 (19.03) [445–916] | 2999 [2919–3065] | 1903 (38.82) [1837–1983] |

| TEX | 4755 | 589 (15.88) [387–768] | 3117 [2990–3209] | 1638 (34.45) [1546–1765] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Trapina, I.; Martins, M.; Plavina, S.; Malakovska, D.; Krasnevska, N.; Paramonovs, J.; Kairisa, D.; Paramonova, N. Comparison of Genomic Variation and Population Structure of Latvian Dark-Head with Other Breeds in Latvia Using Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms. Agriculture 2026, 16, 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010086

Trapina I, Martins M, Plavina S, Malakovska D, Krasnevska N, Paramonovs J, Kairisa D, Paramonova N. Comparison of Genomic Variation and Population Structure of Latvian Dark-Head with Other Breeds in Latvia Using Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms. Agriculture. 2026; 16(1):86. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010086

Chicago/Turabian StyleTrapina, Ilva, Maris Martins, Samanta Plavina, Daniela Malakovska, Nikole Krasnevska, Jegors Paramonovs, Daina Kairisa, and Natalia Paramonova. 2026. "Comparison of Genomic Variation and Population Structure of Latvian Dark-Head with Other Breeds in Latvia Using Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms" Agriculture 16, no. 1: 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010086

APA StyleTrapina, I., Martins, M., Plavina, S., Malakovska, D., Krasnevska, N., Paramonovs, J., Kairisa, D., & Paramonova, N. (2026). Comparison of Genomic Variation and Population Structure of Latvian Dark-Head with Other Breeds in Latvia Using Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms. Agriculture, 16(1), 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010086