Forecasting Crop Yields in Rainfed India: A Comparative Assessment of Machine Learning Baselines and Implications for Precision Agribusiness

Abstract

1. Introduction

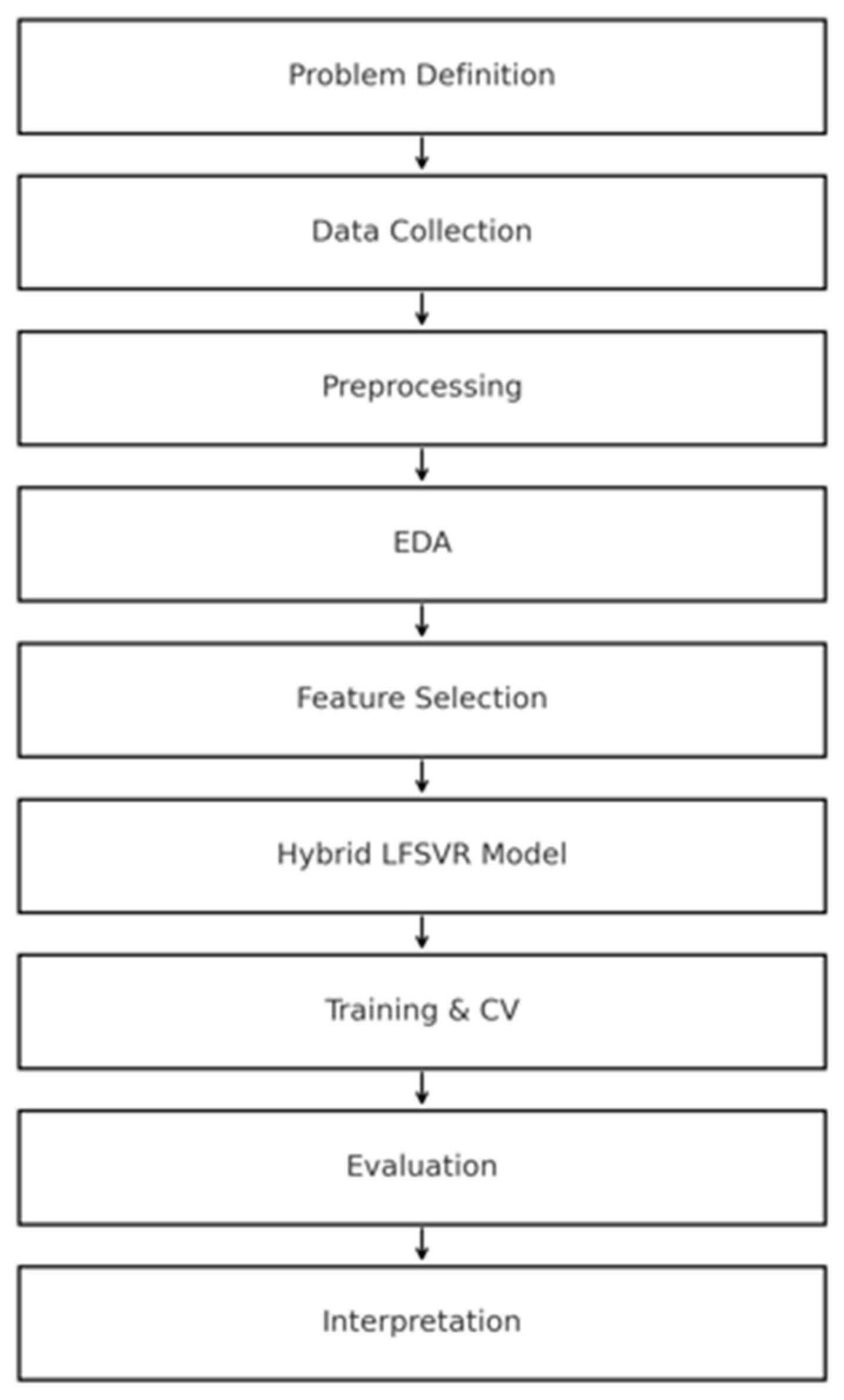

2. Materials and Method

2.1. Study Area and Dataset Description

Data Validity and Reliability

2.2. Data Preprocessing

2.3. Exploratory Data Analysis

2.4. Baseline Models

2.4.1. Linear Regression (LR)

2.4.2. Random Forest (RF)

2.4.3. Support Vector Regression (SVR)

2.5. Proposed LFSVR Based Hybrid Model

2.6. Training and Validation

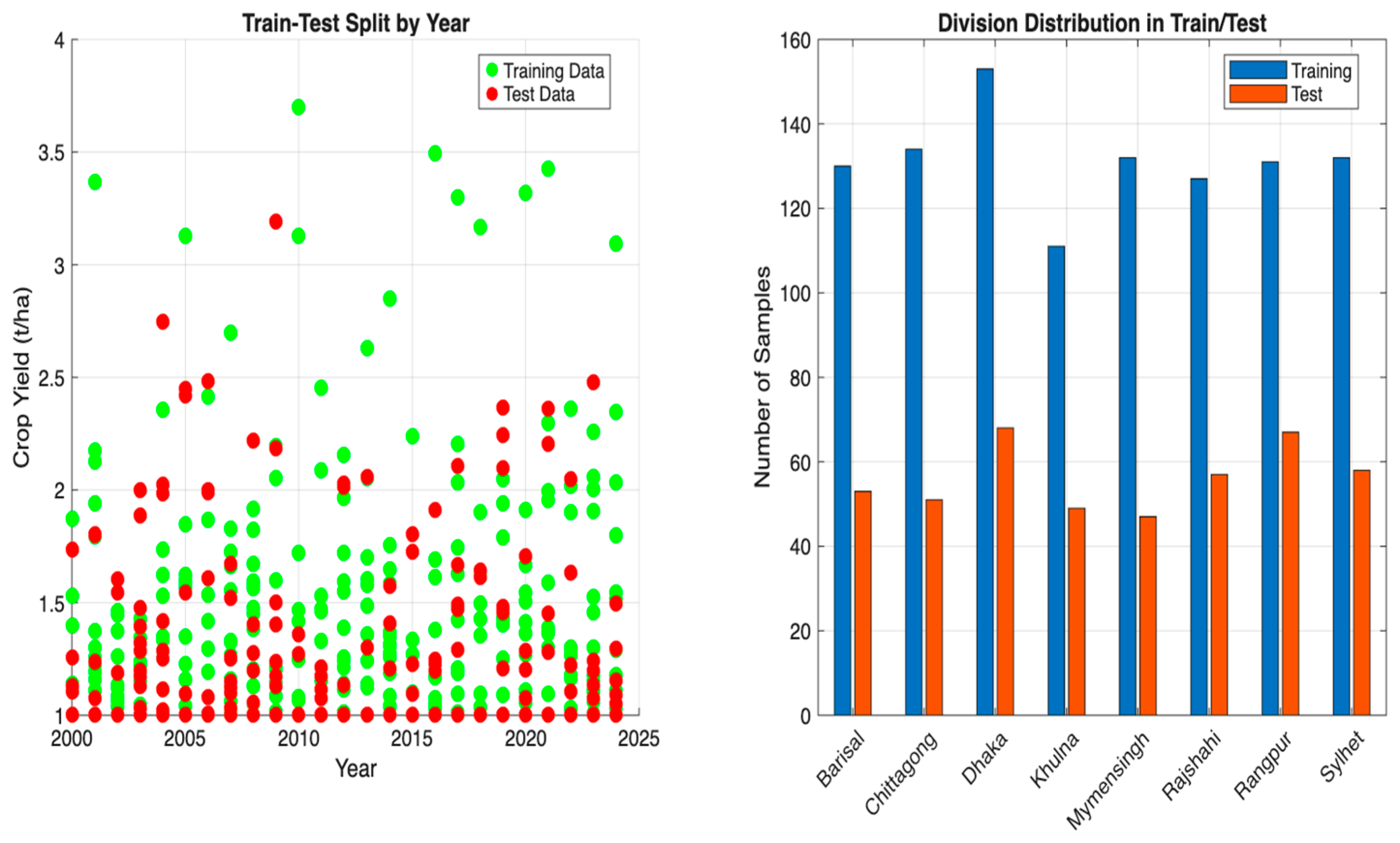

2.7. Performance Evaluation

3. Results

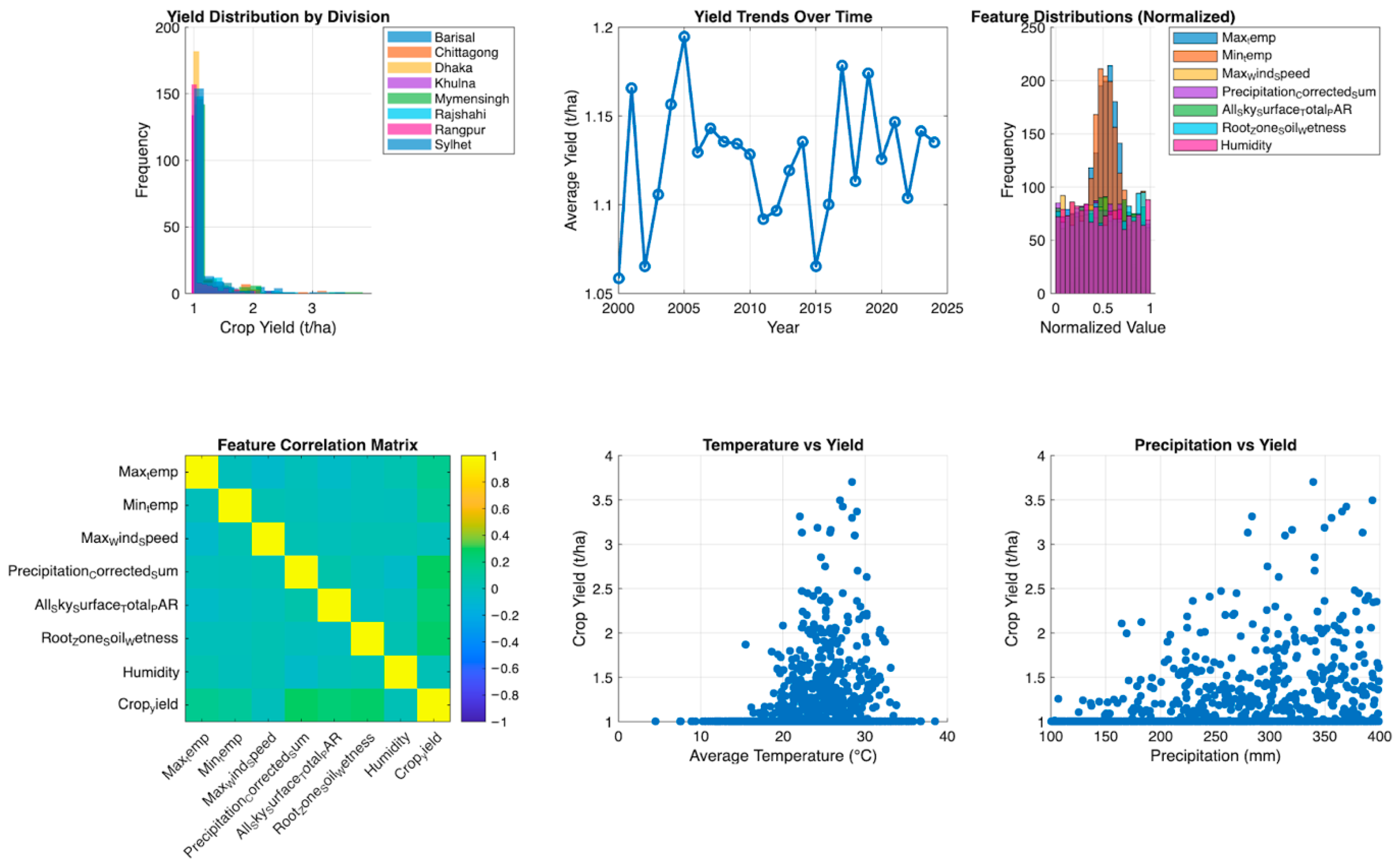

3.1. Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA)

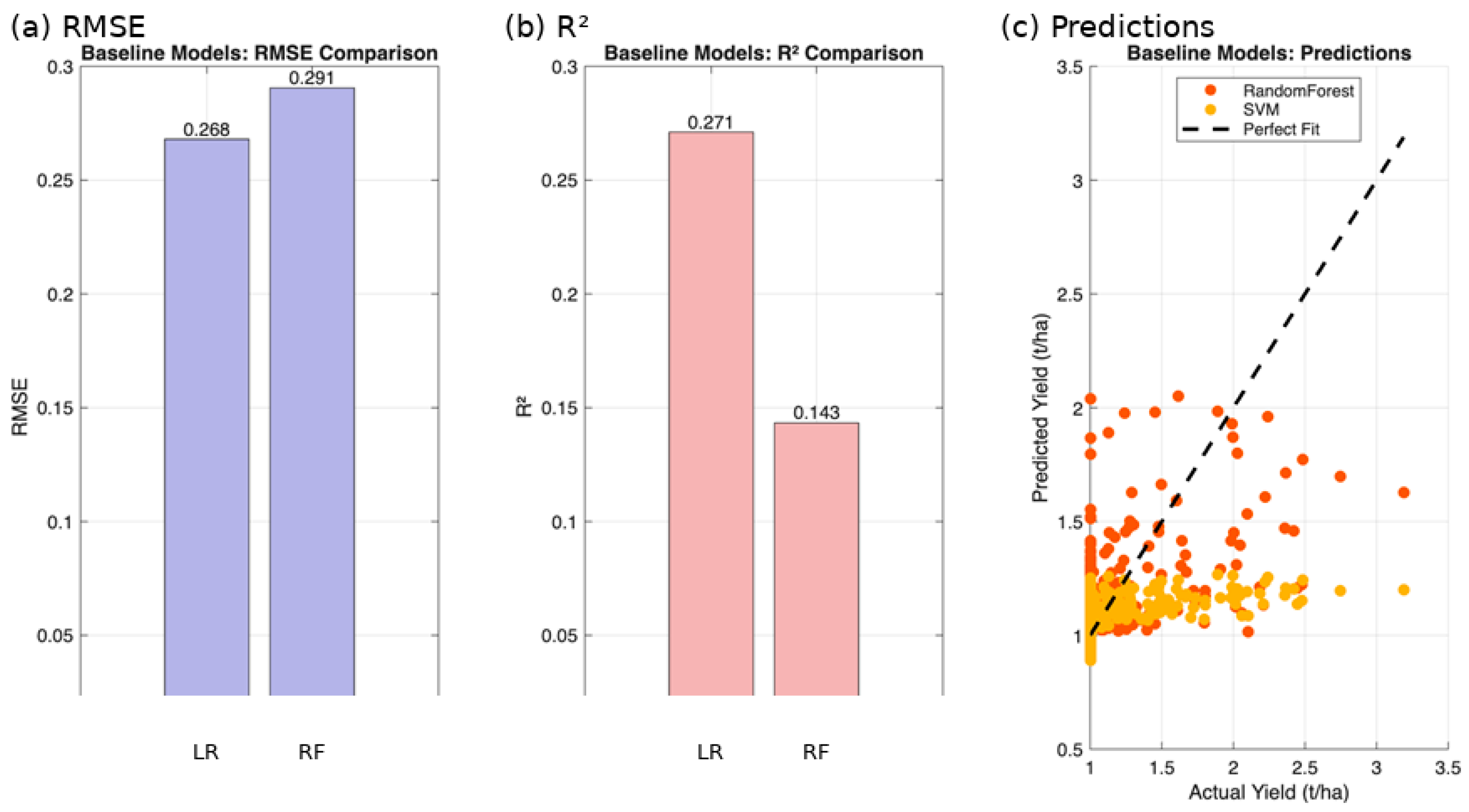

3.2. Baseline Model Evaluation: Linear Regression vs. Random Forest

3.3. Visualizations of Yield and Climatic Relationships

3.4. Temporal and Regional Stratification of the Dataset

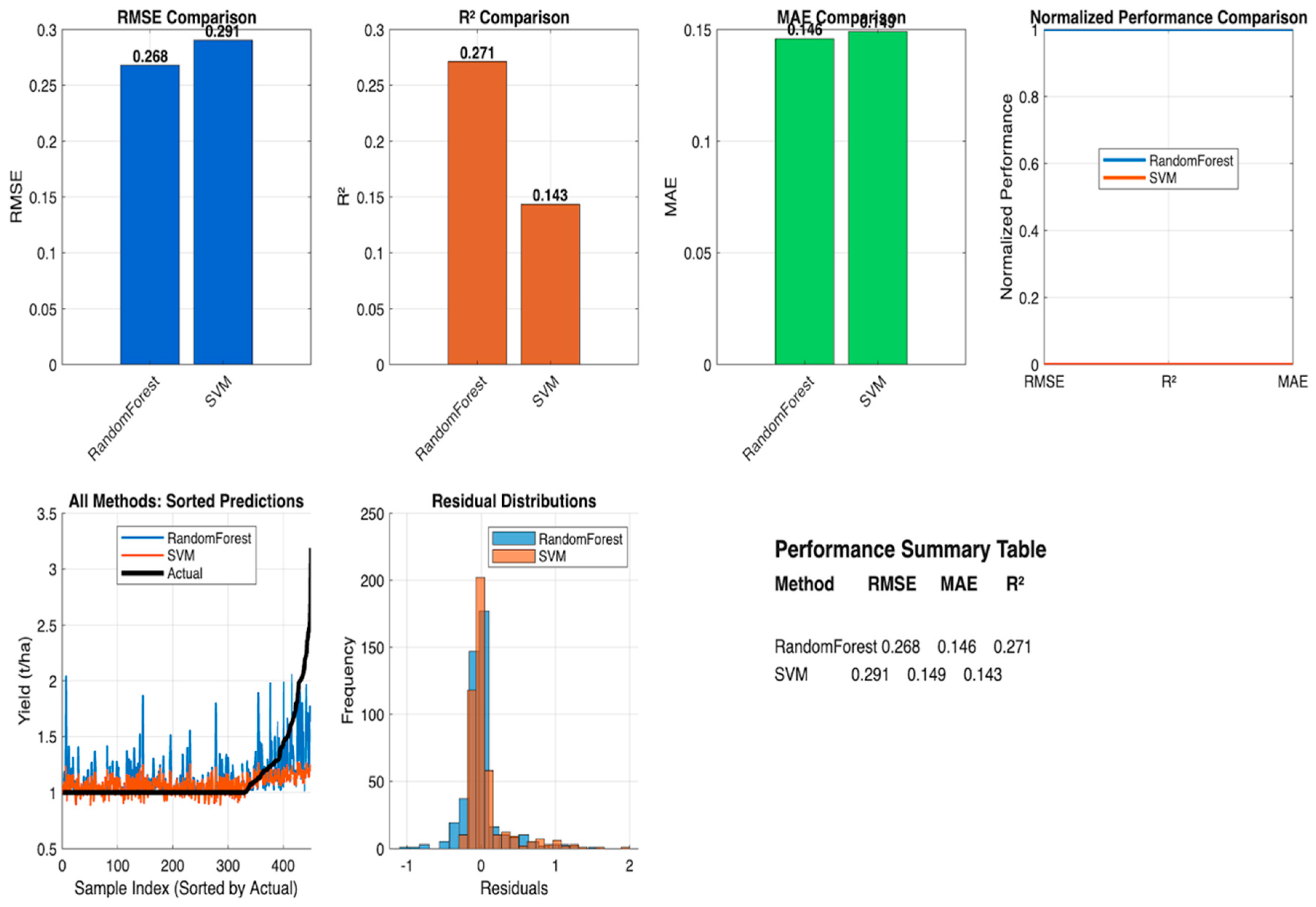

3.5. Benchmarking: Random Forest vs. Support Vector Regression

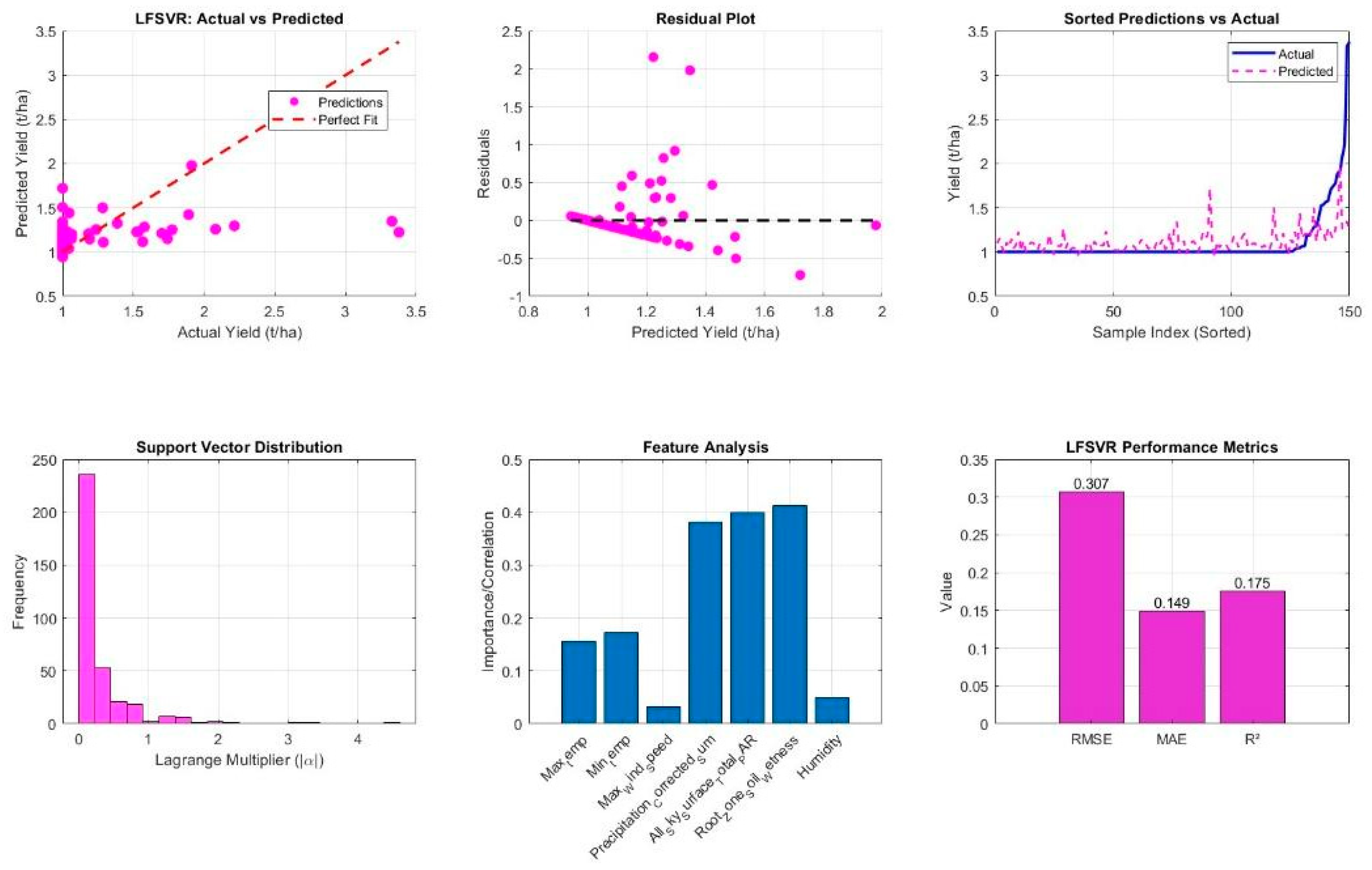

3.6. Performance Evaluation of the Proposed LFSVR Hybrid Model

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of LFSVR Hybrid Model Performance

4.2. Managerial Implementation and Strategic Implications for Precision Agribusiness

4.3. Operational Benefits for Agribusiness

4.4. Challenges and Constraints for Real-World Implementation

4.5. Synthesis and Broader Implications

4.6. Limitations of the Research

5. Conclusions

Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RF | Random Forest |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| SVR | Support Vector Regression |

| LR | Linear Regression |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory Network |

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| EVI | Enhanced Vegetation Index |

| MODIS | Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer |

| AR(1) | First-Order Autoregressive Model |

| JB | Jarque–Bera Statistic |

| DW | Durbin–Watson Statistic |

| VIF | Variance Inflation Factor |

| OOB | Out-of-Bag Error |

| CV | Cross-Validation |

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| R2 | Coefficient of Determination |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

| RSS | Residual Sum of Squares |

| BP | Breusch–Pagan Test |

| Q | Ljung–Box Statistic |

Appendix A

| Symbol/Variable | Definition | Context |

|---|---|---|

| Total number of observations/samples in the dataset (e.g., n ≈ 1250) | Preprocessing | |

| Target variable: Crop yield (tons per hectare, t/ha), with range y ∈ [0.5,4] | Dataset description | |

| is a normalized environmental feature | Model formulation Predictor matrix | |

| Individual predictor variable ): e.g., MaxTemp (maximum temperature, °C), MinTemp (minimum temperature, °C), AvgTemp (average temperature, °C), Precip (precipitation, mm), RelHum (relative humidity, %), WindSpd (wind speed, m/s), SoilpH (soil pH) | Preprocessing | |

| Preprocessing | ||

| Normalization | ||

| Standard deviation of feature | Normalization | |

| Training dataset (80% of data, years 2000–2015, $$) | Preprocessing | |

| Test dataset (20% of data, years 2016–2025, $$) | Preprocessing | |

| is standard deviation of ) | EDA: Skewness coefficient | |

| EDA: Kurtosis | ||

| (chi-squared distribution) | EDA: Jarque–Bera | |

| is white noise) | EDA AR(1) model: | |

| EDA: Durbin-Watson | ||

| (8 × 8 including ) | EDA: Pearson matrix | |

| ) | EDA: Pearson correlation coefficient: | |

| is probability mass function) | EDA: Mutual information | |

| ) | EDA: Variance Inflation Factor | |

| Predicted yield for observation | Model predictions | |

| (: intercept) | LR formulation | |

| (design matrix row) | LR formulation | |

| ) | Model degrees of freedom | |

| LR estimation | ||

| LR inference | ||

| Breusch-Pagan test statistic: from auxiliary regression of squared residuals ) | LR: Heteroscedasticity test | |

| ) | RF formulation | |

| Prediction from the -th decision tree | RF aggregation | |

| Node index in decision tree | RF splitting | |

| Mean Squared Error at node | RF split criterion | |

| Number of child nodes at split | RF splitting | |

| Weight of child node ) | RF splitting | |

| RF splitting | ||

| RF splitting | ||

| Out-of-bag prediction for observation i | RF generalization estimate | |

| ) | RF interpretability | |

| : proportions in left/right child) | RF feature importance | |

| Weight vector in SVR hyperplane | SVR primal | |

| Bias term in SVR hyperplane | SVR primal | |

| penalizes underestimation) | SVR constraints | |

| ) | SVR trade-off | |

| ) | SVR insensitivity margin | |

| Feature map to high-dimensional space | SVR kernel trick | |

| SVR duality | ||

| : feature dimensionality) | SVR RBF | |

| ) | SVR prediction | |

| Set of support vectors (indices where $$ 0 <) | \alpha_i − \alpha_i^* | |

| (CV) | Number of folds in cross-validation (K = 5) | Training |

| in CV | CV procedure | |

| CV-MSE | ||

| CV-MSE | ||

| Cross-validated Mean Squared Error: | Hyperparameter tuning | |

| Model selection | ||

| Evaluation | ||

| Mean Absolute Error: $$ \text{MAE} = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i = 1}^n | y_i − \hat{y}_i | |

| Evaluation | ||

| Evaluation | ||

| Ljung–Box statistic: : lags) | Residual diagnostics | |

| Clark-West test | ||

| Clark-West test statistic: (for nested models 1 superior to 2) | Model comparison |

References

- Mishra, A.K.; Singh, R. Climate vulnerability in rainfed farming: Analysis from Indian watersheds. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, D.; Mahdi, A. Feasibility of machine learning-based rice yield prediction in India at the district level using climate reanalysis data. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.07967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Guan, K.; Peng, B.; Wei, S.; Zhao, L. Machine learning-based modeling of spatio-temporally varying responses of rainfed corn yield to climate, soil, and management in the U.S. Corn Belt. Front. Artif. Intell. 2021, 4, 647999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paudel, D.; de Wit, A.; Boogaard, H.; Marcos, D.; Osinga, S.; Athanasiadis, I.N. Interpretability of deep learning models for crop yield forecasting. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 206, 107663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaki, S.; Wang, L. Crop yield prediction using deep neural networks. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chlingaryan, A.; Sukkarieh, S.; Whelan, B. Machine learning approaches for crop yield prediction and nitrogen status estimation in precision agriculture: A review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 151, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuradusenge, M.; Hitimana, E.; Hanyurwimfura, D.; Rukundo, P.; Mtonga, K.; Mukasine, A.; Uwitonze, C.; Ngabonziza, J.; Uwamahoro, A. Crop yield prediction using machine learning models: Case of Irish potato and maize. Agriculture 2023, 13, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, M.J.; Islam, M.S.; Uddin, J.; Samad, M.A.; Sainz-De-Abajo, B.; Ramírez Vargas, D.L.; Ashraf, I. Incorporating meteorological data and pesticide information to forecast crop yields using machine learning. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 47768–47786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sintayehu, G.; Ebstu, E.T.; Akili, D. Assessment of surface irrigation potential availability using GIS in Gilgel Abbay Catchment, Ethiopia. Res. Sq. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirthiga, S.M.; Patel, N.R. In-season wheat yield forecasting at high resolution using regional climate model and crop model. AgriEngineering 2022, 4, 1054–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfaye, K.; Takele, R.; Shelia, V.; Lemma, E.; Dabale, A.; Traoré, P.C.S.; Solomon, D.; Hoogenboom, G. High spatial resolution seasonal crop yield forecasting for heterogeneous maize environments in Oromia, Ethiopia. Clim. Serv. 2023, 32, 100425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordoñez, L.; Vallejo, E.; Amariles, D.; Mesa, J.; Esquivel, A.; Llanos-Herrera, L.; Prager, S.D.; Segura, C.; Valencia, J.J.; Duarte, C.J.; et al. Applying agroclimatic seasonal forecasts to improve rainfed maize management in Colombia. Clim. Serv. 2022, 28, 100333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, L.; Zou, Y.; Cui, X.; Kattel, G.R.; Shang, Y.; Zhu, J. Predicting China’s maize yield using multi-source datasets and machine learning algorithms. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanthanaporn, U.; Supit, I.; Chaowiwat, W.; Hutjes, R.W.A. Skill of rice yield forecasting over Mainland Southeast Asia using ECMWF SEAS5 and WOFOST. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2024, 351, 110001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Mukhoti, S.; Sharma, P. Quantifying rainfall-induced climate risk in rainfed agriculture. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 319, 109775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Chun, J.A.; Kim, D.; Sitthikone, M. Climate risk management for rainfed rice yield using APCC MME forecasts. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 274, 107976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.H.; Resop, J.P.; Mueller, N.D.; Fleisher, D.H.; Yun, K.; Butler, E.E.; Timlin, D.J.; Shim, K.-M.; Gerber, J.S.; Reddy, V.R.; et al. Random forests for global and regional crop yield predictions. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahhosseini, M.; Hu, G.; Archontoulis, S.V. Forecasting corn yield with machine learning ensembles. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 709008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Klompenburg, T.; Kassahun, A.; Catal, C. Crop yield prediction using machine learning: A systematic literature review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 177, 105709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyndman, R.J.; Athanasopoulos, G. Forecasting: Principles and Practice, 2nd ed.; OTexts: Melbourne, Australia, 2018; Available online: https://otexts.com/fpp2/ (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Friedman, J. The Elements of Statistical Learning, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Box, G.E.P.; Jenkins, G.M.; Reinsel, G.C.; Ljung, G.M. Time Series Analysis: Forecasting and Control, 5th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A.; Mehrotra, R. An information-theoretic alternative for hydrologic forecasting evaluation. J. Hydrol. 2014, 512, 90–103. [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge, J.M. Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach, 6th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, M.; Silge, J. Tidy Modeling with R, 2nd ed.; O’Reilly Media: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Vapnik, V. The Nature of Statistical Learning Theory; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Wolpert, D.H. Stacked generalization. Neural Netw. 1992, 5, 241–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R.; Ahmad, A. A hybrid feature selection and ML framework for yield prediction. In Neural Computing and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, H. A stacking ensemble framework for forest biomass estimation. GISci. Remote Sens. 2025, 62, 230–247. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Q. Comparative evaluation of ML models for maize yield under climate variability. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 209, 107995. [Google Scholar]

- Jarro-Espinal, I.; Huanuqueño-Murillo, J.; Quille-Mamani, J.; Quispe-Tito, D.; Ramos-Fernández, L.; Pino-Vargas, E.; Torres-Rua, A. Field-scale rice yield prediction in Peru using LR, RF, and SVR. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathod, S.; Sailaja, B.; Bandumula, N.; Kumar, S.A.; Prasanna, P.A.L.; Jeyakumar, P.; Waris, A.; Muthuraman, P.; Sundaram, R.M. Time Series and Artificial Intelligence Models for Forecasting Agricultural Data; ICAR-IIRR: Haiderabad, India, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- García, L.; González-Sánchez, A.; Jiménez, F.; Castellanos, J. Best practices for ML in crop yield prediction. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 210, 107893. [Google Scholar]

- Khanna, A.; Kaur, S.; Gupta, R. Cloud-edge AI architectures for precision agriculture. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 215, 108560. [Google Scholar]

- Ramaprasad, A.; Gowrish, R.; Mehta, V.K. A Digitalisation Roadmap for Climate-Smart Agriculture in India; T20 Policy Brief: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, J.V.; Aggarwal, P.K.; Roth, C.H.; Chaves, J. AI for agricultural resilience. Agric. Syst. 2021, 192, 103196. [Google Scholar]

- Basso, B.; Cammarano, D.; De Vita, P. Remotely sensed vegetation indices and machine learning for yield forecasting and climate risk management in rainfed cropping systems. Agric. Syst. 2019, 168, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Klerkx, L.; Jakku, E.; Labarthe, P. Digital agriculture and smart farming: A social science review. NJAS—Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2019, 90–91, 100315. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.M.; Martin, A.C.; Reza, M. Limitations and challenges of ML-based crop yield prediction under heterogeneous agroecosystems. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 209, 107849. [Google Scholar]

- Rehman, A.; Khan, M.A.; Ali, Z.; Ahmad, I. Hybrid deep learning and ensemble frameworks for satellite-driven crop yield forecasting. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 215, 108671. [Google Scholar]

| Method | RMSE | MAE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RF | 0.268 | 0.146 | 0.271 |

| SVM | 0.291 | 0.149 | 0.143 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Karbassi Yazdi, A.; Durán, C.; Derpich, I.; González, G.V. Forecasting Crop Yields in Rainfed India: A Comparative Assessment of Machine Learning Baselines and Implications for Precision Agribusiness. Agriculture 2026, 16, 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010065

Karbassi Yazdi A, Durán C, Derpich I, González GV. Forecasting Crop Yields in Rainfed India: A Comparative Assessment of Machine Learning Baselines and Implications for Precision Agribusiness. Agriculture. 2026; 16(1):65. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010065

Chicago/Turabian StyleKarbassi Yazdi, Amir, Claudia Durán, Iván Derpich, and Gonzalo Valdés González. 2026. "Forecasting Crop Yields in Rainfed India: A Comparative Assessment of Machine Learning Baselines and Implications for Precision Agribusiness" Agriculture 16, no. 1: 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010065

APA StyleKarbassi Yazdi, A., Durán, C., Derpich, I., & González, G. V. (2026). Forecasting Crop Yields in Rainfed India: A Comparative Assessment of Machine Learning Baselines and Implications for Precision Agribusiness. Agriculture, 16(1), 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010065