The Impact of New Agricultural Management Entities’ Participation on the Transfer Price of Contracted Land Management Rights: Evidence from Northeast China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

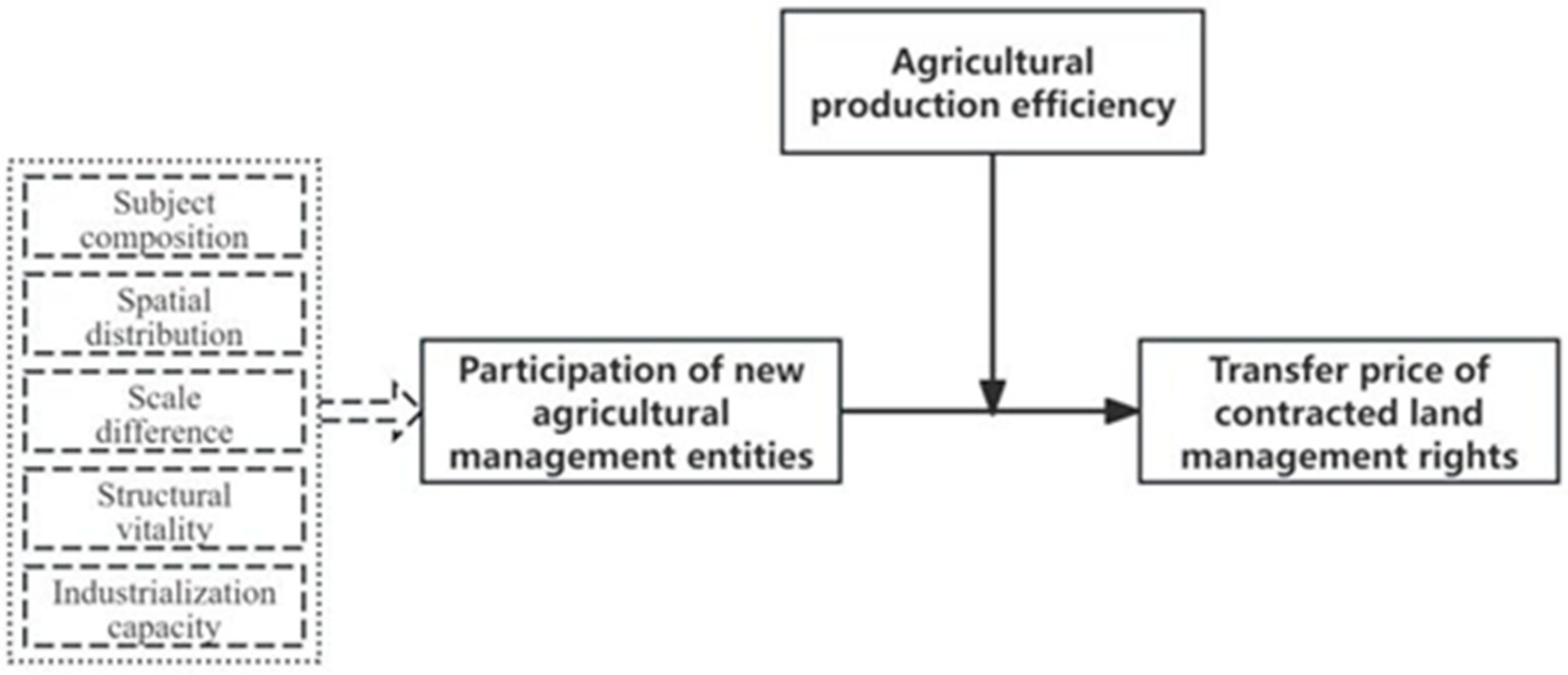

2.1. The Impact of New Agricultural Management Entities’ Participation on the Transfer Prices of Contracted Land Management Rights

2.2. The Moderating Effect of Agricultural Production Efficiency

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Sources

3.2. Variable Setting

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

3.2.2. Independent Variable

3.2.3. Moderating Variable

3.2.4. Control Variables

3.3. Model Selection

3.3.1. Baseline Regression Model

3.3.2. Moderation Effect Model

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Baseline Regression Results and Analysis

4.2. Robustness Tests

4.3. Discussion on Endogeneity

4.4. Moderating Effect Analysis

4.5. Heterogeneity Analysis

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Luo, B.; Geng, P. New quality agricultural productivity: Theoretical framework, core concepts, and enhancement pathways. Issues Agric. Econ. 2024, 4, 13–26. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Tong, B.; Zhang, J. How did the land contract disputes evolve? Evidence from the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China. Land 2023, 12, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yuan, S.; Wang, J.; Cheng, J.; Zhu, D. How do the different types of land costs affect agricultural crop-planting selections in China? Land 2022, 11, 1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deaton, B.J.; Lawley, C. A survey of literature examining farmland prices: A Canadian focus. Can. J. Agric. Econ./Rev. Can. d’agroeconomie 2022, 70, 95–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, B.; Luo, M. The impact of rural collective property rights system reform on the establishment of new agricultural operators. Econ. Surv. 2024, 41, 44–55. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Chang, Y.; Zhu, D. Effect of farmland cost on the scale efficiency of agricultural production based on farmland price deviation. Habitat. Int. 2023, 132, 102745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koguashvili, P.; Ramishvili, B. Specific of agricultural land’s price formation. Ann. Agrar. Sci. 2018, 16, 324–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Zhu, S.; Deng, Y.; Teng, L.; Zhao, R. An analysis of the factors of the price of farmland use rights’ circulation-the experience from farmers and regional level. China Rural Surv. 2012, 3, 2–17. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sklenicka, P.; Molnarova, K.; Pixova, K.C.; Salek, M.E. Factors affecting farmland prices in the Czech Republic. Land Use Policy 2013, 30, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koemle, D.; Lakner, S.; Yu, X. The impact of Natura 2000 designation on agricultural land rents in Germany. Land Use Policy 2019, 87, 104013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, H.G.; Li, G.; Rozelle, S. Hazards of expropriation: Tenure insecurity and investment in rural China. Am. Econ. Rev. 2002, 92, 1420–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czyżewski, B.; Matuszczak, A. A new land rent theory for sustainable agriculture. Land Use Policy 2016, 55, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehn, F.; Bahrs, E. Analysis of factors influencing standard farmland values with regard to stronger interventions in the German farmland market. Land Use Policy 2018, 73, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Huang, J. Impacts of agricultural incentive policies on land rental prices: New evidence from China. Food Policy 2021, 104, 102125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Shang, X.; He, P. Paid or free: Government subsidy, farmer differentiation and land transfer Rent. Econ. Probl. 2021, 12, 59–66. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhang, Z. The logic and governance of local government’s participation in the “non-grain” transfer of cultivated land: A case study based on planting and greening of cultivated land. China Land Sci. 2023, 37, 114–123. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Huang, J. Social capital, government guidance and contract choice in agricultural land transfer. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0303392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, T.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, L.; Shi, D.; Duan, X. The impact of multiplex relationships on households’ informal farmland transfer in rural China: A network perspective. J. Rural Stud. 2024, 112, 103419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deininger, K.; Jin, S. Securing property rights in transition: Lessons from implementation of China’s rural land contracting law. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2009, 70, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Jiang, Y.; Luo, B.; Zheng, X. The impact of dialect diversity on rent-free farmland transfers: Evidence from Chinese rural household surveys. Land 2024, 13, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Zheng, Z. Informal agricultural land market: Mechanism and empiricalevidence of “renqing rent” land transfer behavior. Financ. Trade Res. 2020, 31, 27–39. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonhardt, H. How close are they? Using proximity theory to understand the relationship between landlords and tenants of agricultural land. J. Rural. Stud. 2024, 107, 103257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ito, J. An empirical study of land rental development in rural Gansu, China: The role of agricultural cooperatives and transaction costs. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, P.; Mishra, A.K.; Feng, S.; Su, M. From informal farmland rental to market-oriented transactions: Do China’s Land Transfer Service Centers help? J. Agric. Econ. 2025, 76, 74–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Fan, X.; Du, G. Transition through collaboration: New agricultural business entities can promote crop rotation adoption in Heilongjiang, China. Land 2025, 14, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Zhu, C. Development of new agricultural management subject and choice of rural land circulation mode from the perspective of new structural economics: Taking Jiangsu province as an example. J. Northeast Norm. Univ. Philos. Soc. Sci. 2020, 70, 45–53. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. How new agricultural management entities “embedded” into rural society: Theoretical perspective of relational work. J. Northwest AF Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2018, 18, 18–24. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, P.; Von Braun, J.; Abebaw, D.; Müller, M. Impacts of large-scale land investments on income, prices, and employment: Empirical analyses in Ethiopia. World Dev. 2015, 72, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L. Big hands holding small hands: The role of new agricultural operating entities in farmland abandonment. Food Policy 2024, 123, 102605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayne, T.S.; Chamberlin, J.; Traub, L.; Sitko, N.; Muyanga, M.; Yeboah, F.K.; Anseeuw, W.; Chapoto, A.; Wineman, A.; Nkonde, C.; et al. Africa’s changing farm size distribution patterns: The rise of medium-scale farms. Agric. Econ. 2016, 47, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Qin, F. How to overcome the demand dilemma of farmland transfer in China? Evidence from the development of new agricultural operators. J. Manag. World 2022, 38, 84–99. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, T.; Luo, B.; He, Q. Does land rent between acquaintances deviate from the reference point? Evidence from rural China. China World Econ. 2020, 28, 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Peng, Y.; Zheng, L.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, Y.; Kong, R.; Turvey, C.G. Heterogeneous choice in WTP and WTA for renting land use rights in rural China: Choice experiments from the field. Land Use Policy 2022, 119, 106123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, T.; Zhu, D.; Wang, Z.; Li, C. Research on structure differentiation of farmland transfer price: Based on the survey data of five provinces in the Huang-Huai-Hai Region. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2022, 7, 96–108. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Zhu, Z.; Zhou, X. Agricultural mechanization and cropland abandonment in rural China. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2022, 29, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Peng, J.; Chen, Y.; Cao, Q. Will agricultural infrastructure construction promote land transfer? Analysis of China’s high-standard farmland construction policy. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wu, H. Cooperative-owned enterprises driving the adoption of rice-crab integrated farming and resource conservation effects: Synergistic mechanisms of organization, technology, and policy. J. Agric. Resour. Environ. 2025, 42, 1563–1572. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Y.; Ye, S.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, F.; Mi, G. Barriers to the development of agricultural mechanization in the North and Northeast China plains: A farmer survey. Agriculture 2022, 12, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Liang, Q. Agricultural organizations and the role of farmer cooperatives in China since 1978: Past and future. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2018, 10, 48–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Zhou, S. To what extent does agriculture become over-intensivein China: Evidence from farmers’ of Heilongjiang agricultural reclamation. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2024, 6, 4–17. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, G. Research on the relationship between information technology input, technological innovation dynamic capabilities and enterprise performance. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2019, 36, 100–107. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Y. Rural regional system and rural revitalization strategy in China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2019, 74, 2511–2528. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Duan, J.; Zhan, L.; Yan, C.; Huang, Z. Multifactor configurational pathways driving the eco-efficiency of cultivated land utilization in China: A dynamic panel QCA. Land 2025, 14, 1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Deng, Y. Operation scale, adoption of black land protection techniques and farmland management efficiency: Moderating effect of farmland fragmentation. China Land Sci. 2025, 39, 70–81. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Zhu, Z. A note: Reducing cropland abandonment in China-do agricultural cooperatives play a role? J. Agric. Econ. 2020, 71, 929–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavalloni, M.; D’Alberto, R.; Raggi, M.; Viaggi, D. Farmland abandonment, public goods and the CAP in a marginal area of Italy. Land Use Policy 2021, 107, 104365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Qian, W. The impact of land certification on cropland abandonment: Evidence from rural China. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2022, 14, 509–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, A.; Yang, Q. The extent, drivers and production loss of farmland abandonment in China: Evidence from a spatiotemporal analysis of farm households survey. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 414, 137772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, X.; Xin, L. Differentiation of scale-farmland transfer rent and its influencing factors in China. Acta Geogr. Sin 2021, 76, 753–763. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Luo, X.; Zhang, J. Social supervision, group identity and farmers’ domestic waste centralized disposal behavior: An analysis based on mediation effect and regulation effect of the face concept. China Rural Surv. 2019, 2, 18–33. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Zheng, S. The impact of information acquisition channels on farmers’ green control technology behavior. J. Northwest AF Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 23, 109–119. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicator Name | Indicator Definition and Assignment | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participation of new agricultural management entities | Subject composition | Proportion of new agricultural management entities: ratio of the number of various types of new agricultural management entities in the village to the total number of registered households in the village | 0.102 | 0.106 | 0.006 | 0.45 |

| Spatial distribution | Density of new agricultural management entities: ratio of the number of various types of new agricultural management entities in the village to the area of contracted land transferred in the village | 0.068 | 0.054 | 0.008 | 0.208 | |

| Scale difference | Extreme value ratio of land transfer scale: ratio of the maximum land transfer scale to the average land transfer scale in a village | 3.450 | 1.263 | 1.785 | 8.163 | |

| Structural vitality | Number of types of new agricultural management entities: count of specialized households, family farms, farmers’ professional cooperatives, and leading agricultural enterprises in the village | 2.836 | 0.471 | 2 | 4 | |

| Industrialization capacity | Whether there are leading agricultural enterprises in the village: Yes = 1; no = 0 | 0.110 | 0.313 | 0 | 1 |

| Indicator Name | Indicator Definition and Assignment | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agricultural production efficiency | Input indicators | Total capital input per plot, unit: ten thousand Yuan | 0.792 | 3.142 | 0.04 | 94.667 |

| Labor input of land parcel, unit: days | 64.311 | 39.260 | 7 | 240 | ||

| Land parcel scale, unit: hectares | 1.491 | 5.390 | 0.013 | 133.333 | ||

| Output indicators | Total output value of land parcel, unit: Ten Thousand Yuan | 17,442.875 | 10.511 | 0.015 | 291.6 |

| Variable Type | Variable Name | Variable Definition and Assignment | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | Transfer price of contracted land management rights | Actual transfer price, unit: ten thousand Yuan | 1.165 | 0.193 | 0.225 | 1.8 |

| Independent variable | Participation of new agricultural management entities | Calculated via principal component analysis | 0.000 | 0.592 | −0.793 | 1.896 |

| Moderating variable | Agricultural production efficiency | Calculated via the SBM model | 0.502 | 0.153 | 0.171 | 1 |

| Individual characteristics | Gender | Male = 1; female = 0 | 0.859 | 0.348 | 0 | 1 |

| Age | Actual survey value, unit: years | 52.385 | 8.241 | 32 | 77 | |

| Education level | Primary school or below = 1; junior high = 2; senior high = 3; vocational school or technical secondary = 4; college or above = 5 | 1.733 | 0.771 | 1 | 5 | |

| Land parcel characteristics | Parcel area | Actual survey value, unit: hectares | 1.491 | 5.390 | 0.013 | 133.333 |

| Parcel quality | Very poor = 1; poor = 2; average = 3; good = 4; very good = 5 | 3.392 | 0.866 | 1 | 5 | |

| Parcel location | Distance from plot to home, unit: km | 1.699 | 2.253 | 0 | 30 | |

| Status of land transfer contract signing | Yes = 1; no = 0 | 0.346 | 0.476 | 0 | 1 | |

| Land transfer term | Actual survey value, unit: year | 1.046 | 0.359 | 1 | 8 | |

| Household characteristics | Total household population | Actual survey value, unit: person | 3.624 | 1.376 | 1 | 10 |

| Presence of village cadres in the household | Yes = 1; no = 0 | 0.129 | 0.336 | 0 | 1 | |

| Ownership of agricultural machinery | Yes = 1; no = 0 | 0.943 | 0.232 | 0 | 1 | |

| Number of household members engaged in non-agricultural employment | Actual survey value, unit: person | 0.432 | 0.787 | 0 | 6 | |

| Village characteristics | Village’s road condition | Compared to other villages in this township: very poor = 1; poor = 2; average = 3; fair = 4; good = 5 | 3.561 | 0.924 | 1 | 5 |

| Village’s economic development level | Compared to other villages in this township: very low = 1; low = 2; average = 3; high = 4; very high = 5 | 3.444 | 0.614 | 2 | 4 |

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Participation of new agricultural management entities | 0.089 ** (0.041) | 0.104 ** (0.038) |

| Gender | 0.010 (0.026) | |

| Age | 0.003 ** (0.001) | |

| Education level | 0.015 (0.015) | |

| Parcel area | 0.0001 (0.001) | |

| Parcel quality | 0.002 (0.008) | |

| Parcel location | −0.003 (0.05) | |

| Status of land transfer contract signing | 0.015 (0.026) | |

| Land transfer term | −0.053 ** (0.023) | |

| Total household population | 0.010 (0.008) | |

| Presence of village cadres in the household | −0.050 * (0.028) | |

| Ownership of agricultural machinery | 0.030 (0.031) | |

| Number of household members engaged in non-agricultural employment | −0.009 (0.014) | |

| Village’s road condition | 0.032 (0.023) | |

| Village’s economic development level | 0.073 ** (0.034) | |

| Observations | 1231 | 1231 |

| R2 | 0.075 | 0.214 |

| Transfer Price of Contracted Land Management Rights | [0, 0.15] | (0.15, 0.3] | (0.3, 0.45] | (0.45, 0.6] | (0.6, 0.75] | (0.75, 0.9] | (0.9, 1.05] | (1.05, 1.2] | (1.2, 1.35] | (1.35, 1.5] | (1.5, +∞] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assigned value | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| Variable | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|

| Participation of new agricultural management entities | 0.623 ** (0.244) | 0.618 *** (0.232) |

| Control variables | YES | YES |

| Observations | 1231 | 1231 |

| R2; Pseudo R2 | 0.204 | 0.074 |

| Variable | Model 5 | Model 6 |

|---|---|---|

| Participation of new agricultural management entities | 0.071 ** (0.031) | 0.084 *** (0.026) |

| Control variables | NO | YES |

| Observations | 1212 | 1212 |

| R2 | 0.058 | 0.184 |

| Variable | First Stage | Second Stage |

|---|---|---|

| Instrumental variable | 1.064 ** (0.522) | |

| Participation of new agricultural management entities | 0.677 ** (0.304) | |

| Control variables | YES | YES |

| Observations | 1231 | 1231 |

| Wald F-test | 135.66 (16.380) | |

| Variable | Moderating Effect | Low Agricultural Productivity | High Agricultural Productivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participation of new agricultural management entities | 0.105 *** (0.036) | 0.041 (0.033) | 0.143 *** (0.045) |

| Agricultural production efficiency | −0.206 ** (0.081) | ||

| Interaction term | 0.141 ** (0.068) | ||

| Control variables | YES | YES | YES |

| Observations | 1231 | 708 | 523 |

| R2 | 0.242 | 0.203 | 0.268 |

| Variable | Township-Adjacent Villages | Remote Villages | Dryland Parcels | Paddy Parcels |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participation of new agricultural management entities | 0.089 * (0.044) | 0.01 (0.083) | 0.085 ** (0.035) | −0.125 (0.123) |

| Control variables | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observations | 764 | 467 | 978 | 253 |

| R2 | 0.164 | 0.400 | 0.282 | 0.249 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, Z.; Huang, S. The Impact of New Agricultural Management Entities’ Participation on the Transfer Price of Contracted Land Management Rights: Evidence from Northeast China. Agriculture 2026, 16, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010034

Wang Z, Huang S. The Impact of New Agricultural Management Entities’ Participation on the Transfer Price of Contracted Land Management Rights: Evidence from Northeast China. Agriculture. 2026; 16(1):34. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010034

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Zhixiang, and Shanlin Huang. 2026. "The Impact of New Agricultural Management Entities’ Participation on the Transfer Price of Contracted Land Management Rights: Evidence from Northeast China" Agriculture 16, no. 1: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010034

APA StyleWang, Z., & Huang, S. (2026). The Impact of New Agricultural Management Entities’ Participation on the Transfer Price of Contracted Land Management Rights: Evidence from Northeast China. Agriculture, 16(1), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010034