Legume-Based Rotations Enhance Ecosystem Sustainability in the North China Plain: Trade-Offs Between Greenhouse Gas Mitigation, Soil Carbon Sequestration, and Economic Viability

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Gas Sampling and Analysis

2.4. Soil Characteristics

2.5. Crop Yield, Biomass and Economic Benefit Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

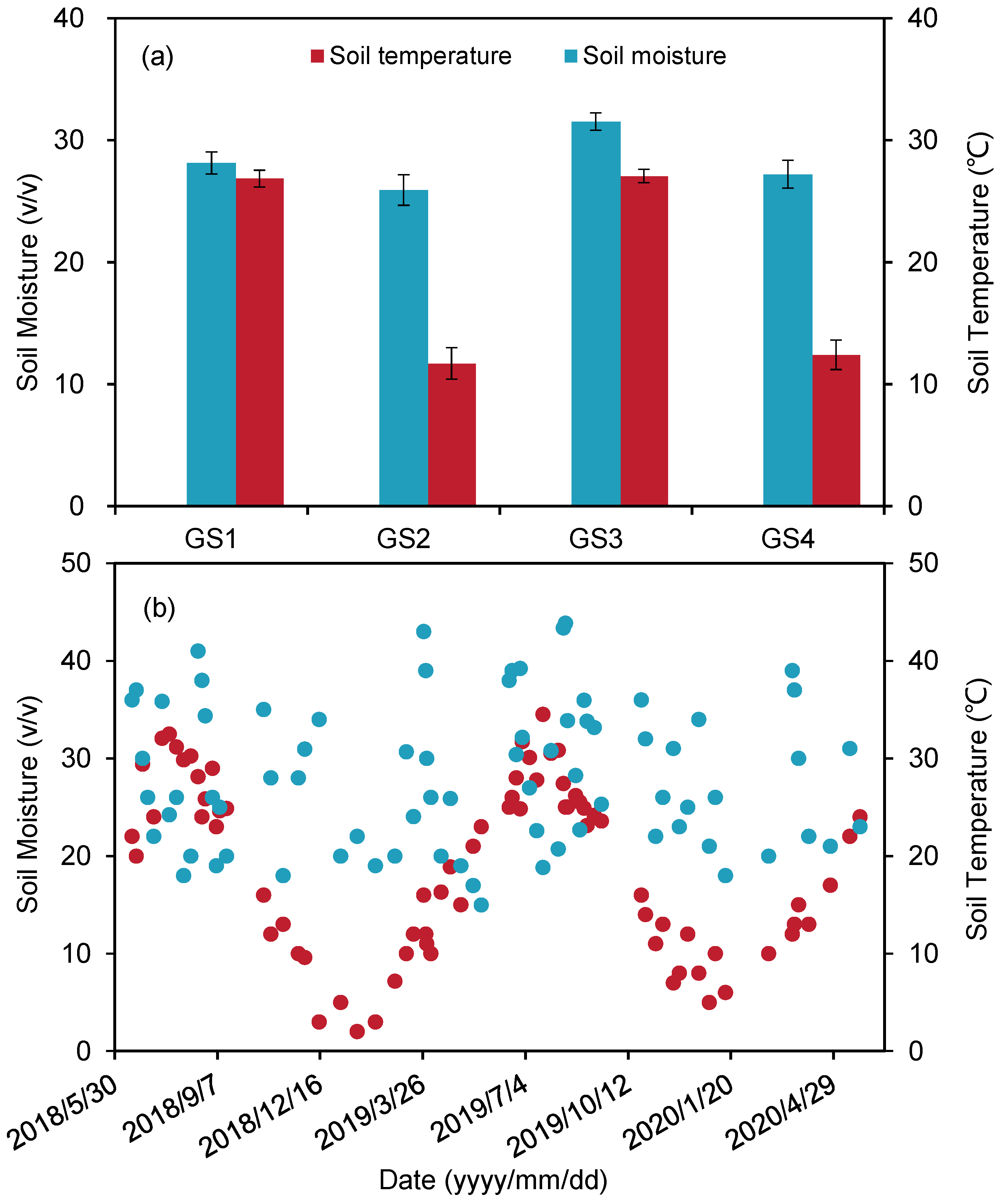

3.1. Soil Biogeochemistry Properties and Nitrogen Dynamics

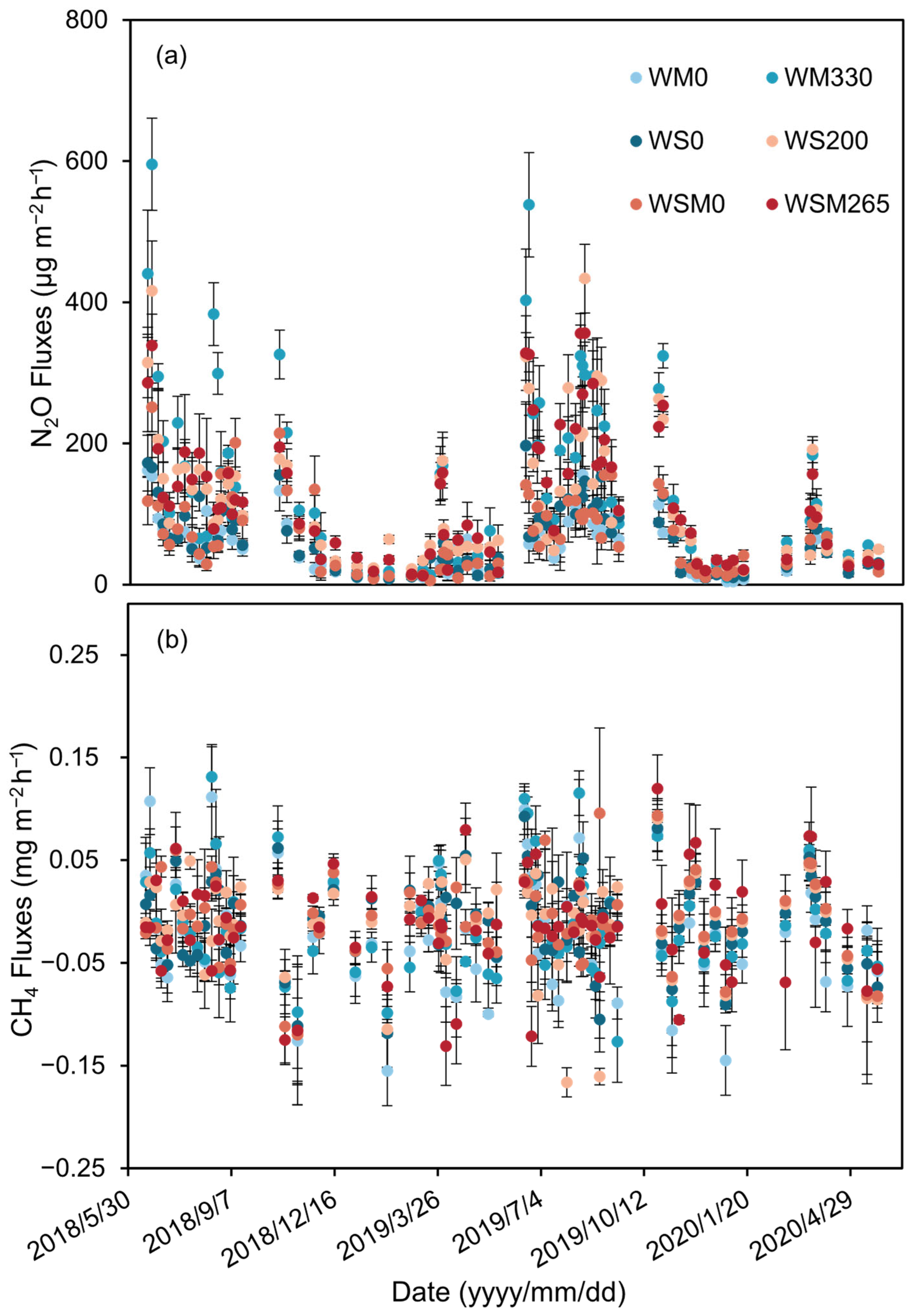

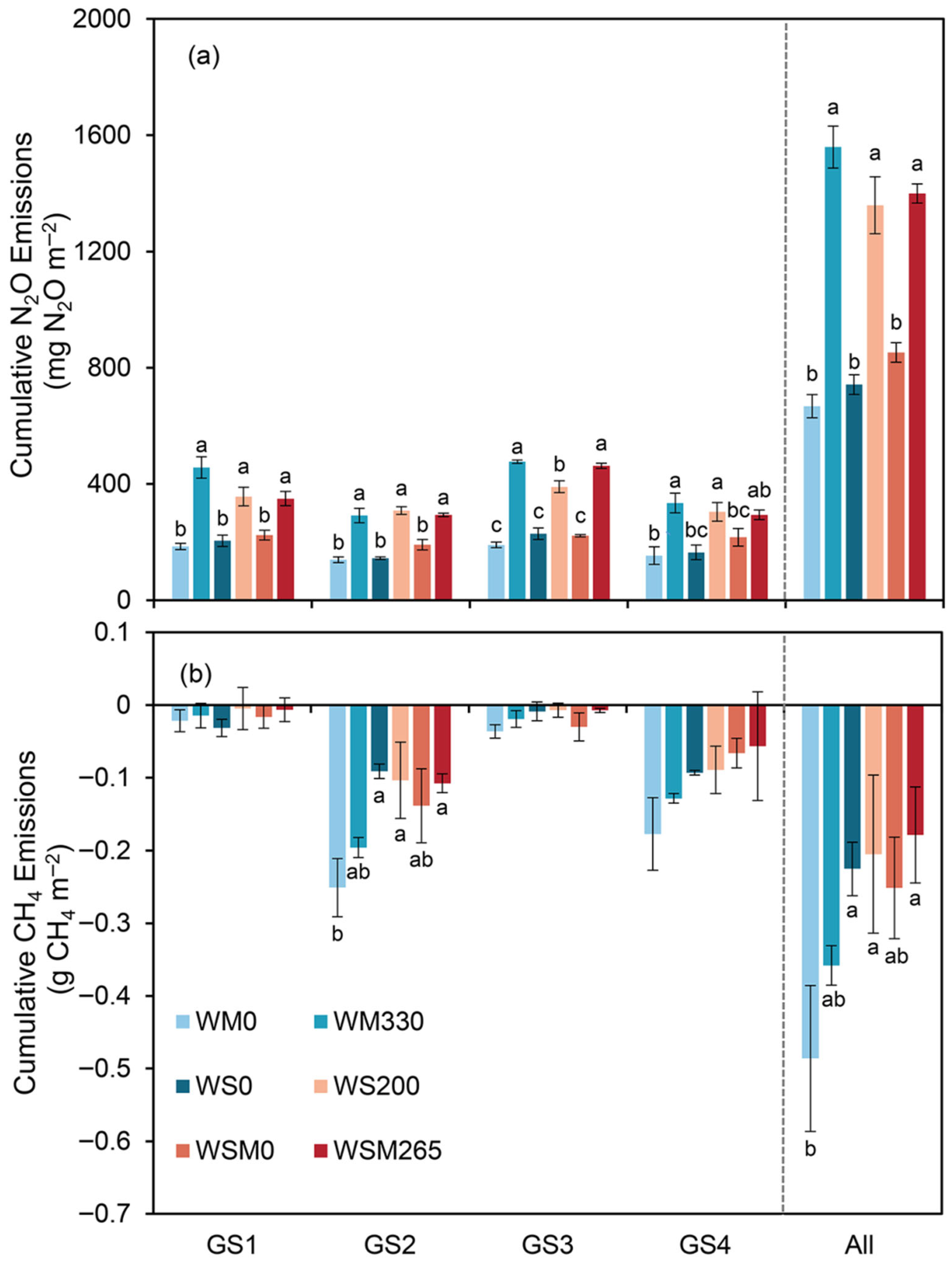

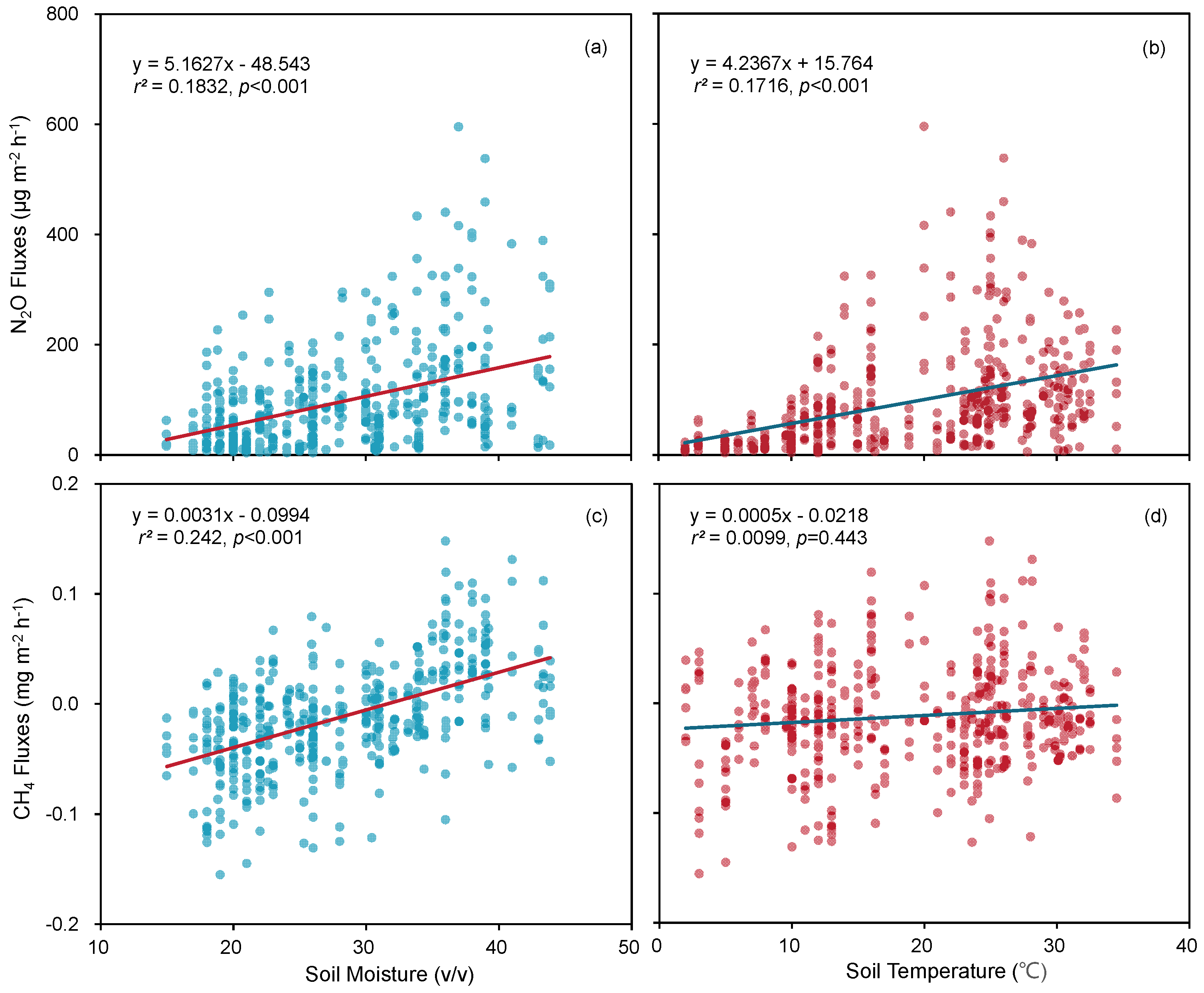

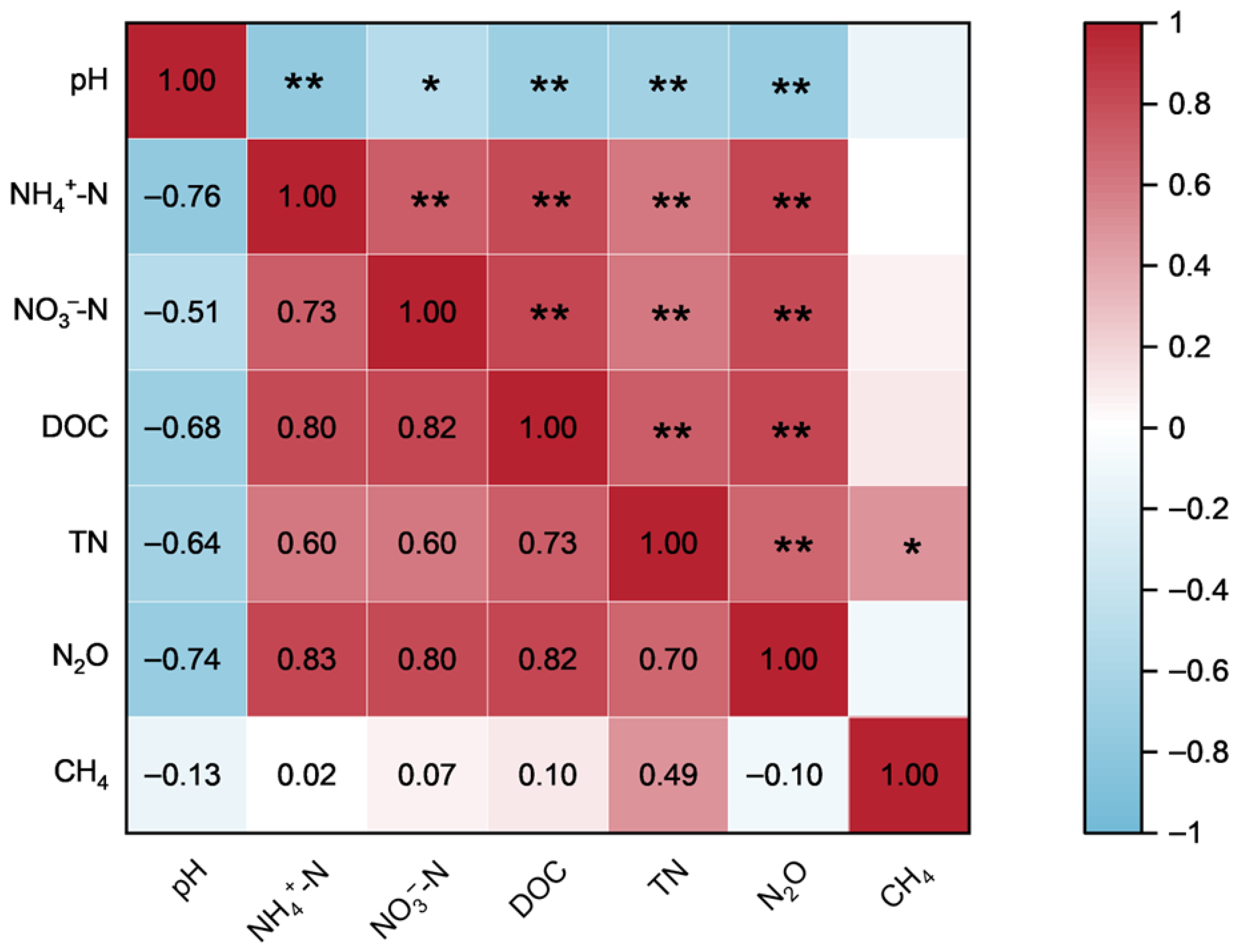

3.2. N2O and CH4 Flux Dynamics and Driving Factors

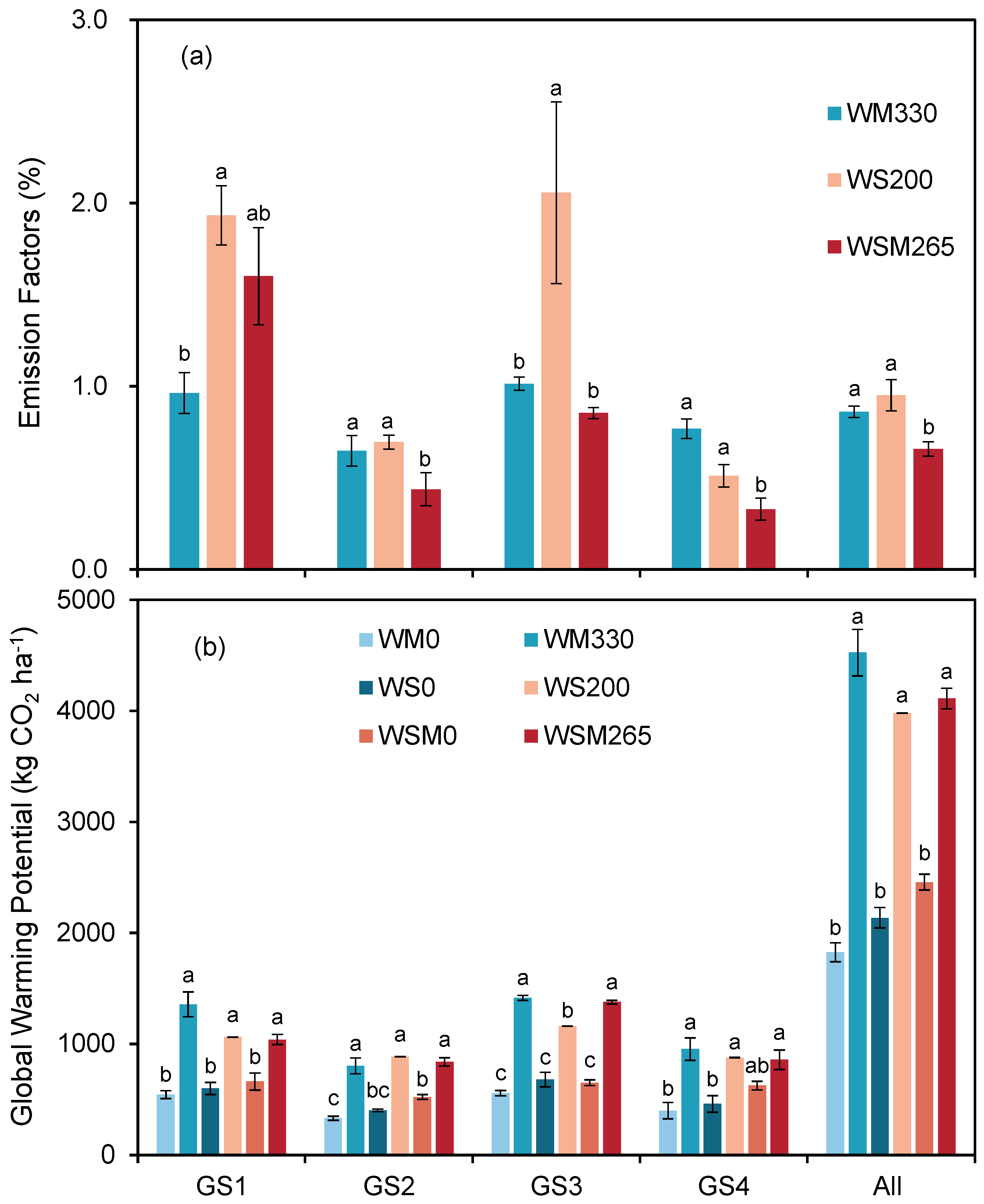

3.3. Emission Factors and Global Warming Potential

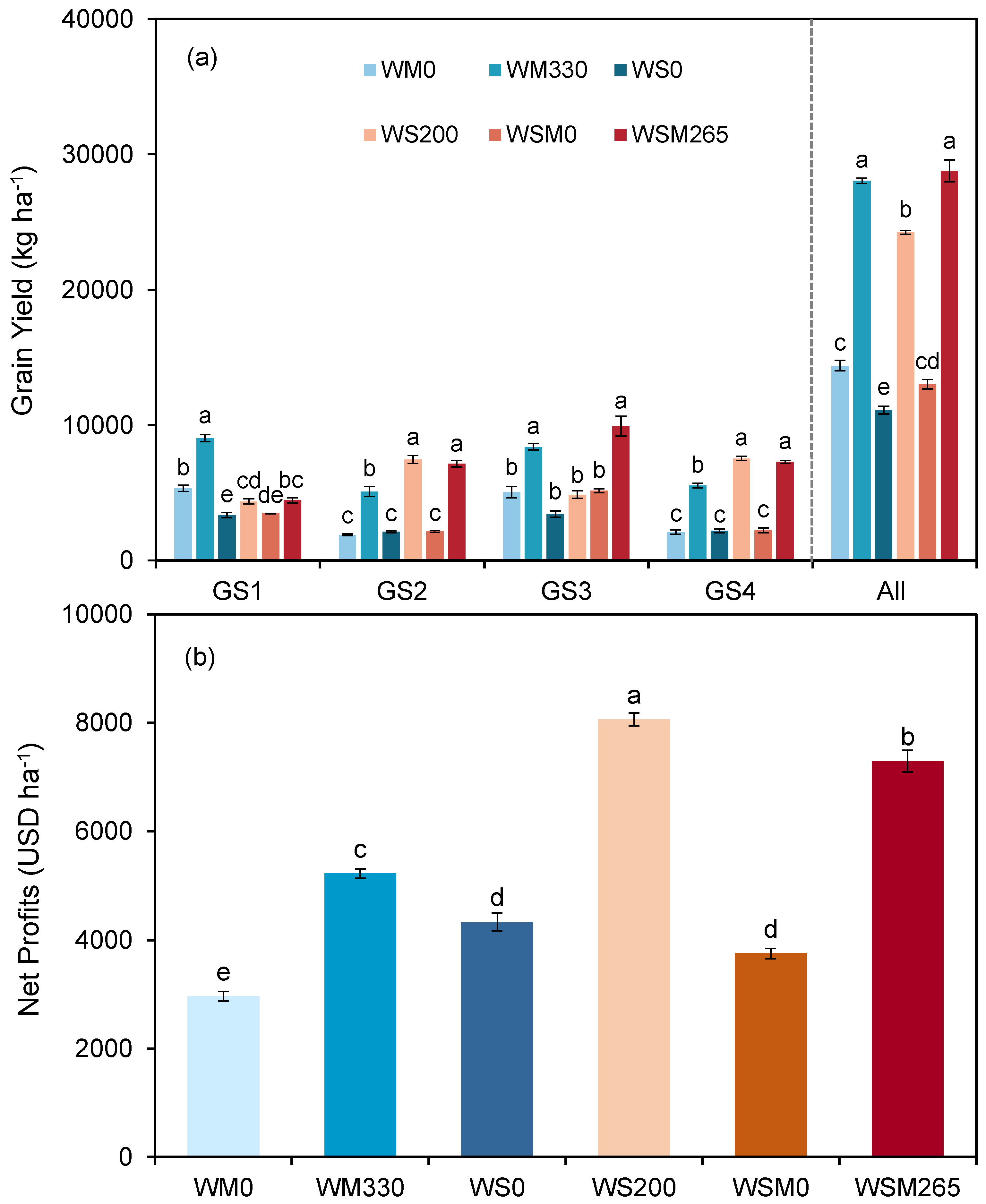

3.4. Crop Yield, Economic Performance, and Integrated Sustainability

4. Discussion

4.1. Legume Rotations Modulate GHG Emissions Through Competing Pathways

4.2. Yield Synergies and Soil Legacy Effects

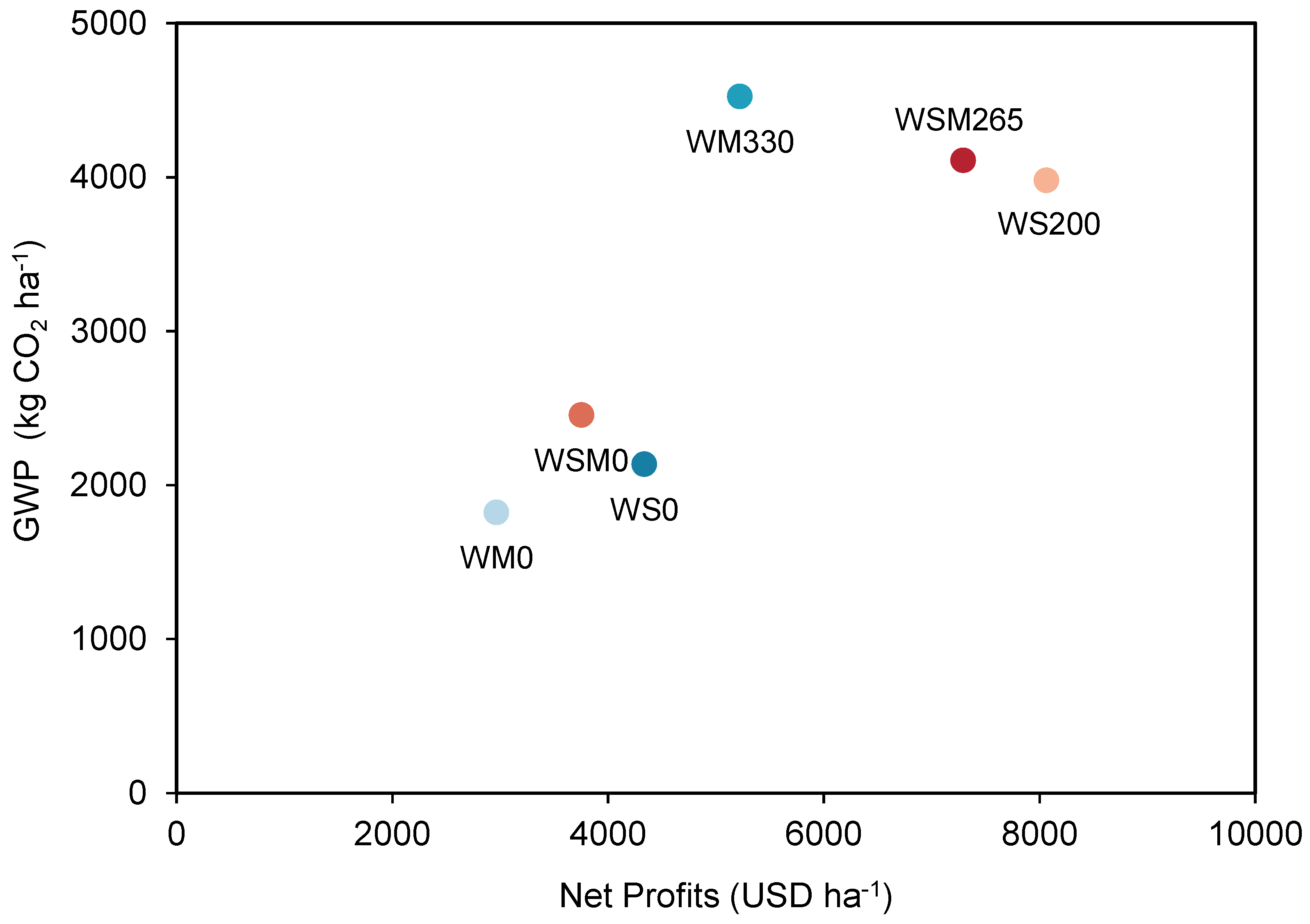

4.3. Reconciling Productivity and Sustainability via Legume Integration

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Goglio, P.; Smith, W.; Grant, B.; Desjardins, R.; Gao, X.; Hanis, K.; Tenuta, M.; Campbell, C.; McConkey, B.; Nemecek, T.; et al. A comparison of methods to quantify greenhouse gas emissions of cropping systems in LCA. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 4010–4017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Behnke, G.; Villamil, M. Cover crop rotations affect greenhouse gas emissions and crop production in Illinois, USA. Field Crop Res. 2019, 241, 107580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Dang, P.; Liao, L.; Song, F.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, M.; Li, G.; Wen, S.; Yang, N.; Pan, X.; et al. Combining slow-release fertilizer and plastic film mulching reduced the carbon footprint and enhanced maize yield on the Loess Plateau. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 147, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Zhang, H.; Chen, X.; Zhang, C.; Ma, W.; Huang, C.; Zhang, W.; Mi, G.; Miao, Y.; Li, X.; et al. Pursuing sustainable productivity with millions of smallholder farmers. Nature 2018, 555, 363–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Tian, H.; Shi, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Pan, S.; Yang, J. Increased greenhouse gas emissions intensity of major croplands in China: Implications for food security and climate change mitigation. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 6116–6133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raseduzzaman, M.; Aluoch, S.; Gaudel, G.; Li, X.; Ali, M.; Timilsina, A.; Bizimana, F.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, C. Cereal legume mixed residue addition increases yield and reduces soil greenhouse gas emissions from fertilized winter wheat in the North China Plain. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainju, U. Dryland soil carbon and nitrogen stocks in response to cropping systems and nitrogen fertilization. Environments 2024, 11, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Xu, Z.; Xue, Y.; Sun, R.; Yang, R.; Cao, X.; Li, H.; Shao, Q.; Lou, Y.; Wang, H.; et al. N2O emissions from soils under short-term straw return in a wheat-corn rotation system are associated with changes in the abundance of functional microbes. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 341, 108217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, N.; Zhai, Z.; Li, H.; Wang, L.; Deng, J. Impacts of nitrogen management and organic matter application on nitrous oxide emissions and soil organic carbon from spring maize fields in the North China Plain. Soil Till. Res. 2020, 196, 104441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Ma, X.; Shen, J.; Chen, D.; Zheng, L.; Ge, T.; Li, Y.; Wu, J. Reduction in net greenhouse gas emissions through a combination of pig manure and reduced inorganic fertilizer application in a double-rice cropping system: Three-year results. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2022, 326, 107799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeuffroy, M.; Baranger, E.; Carrouée, B.; de Chezelles, E.; Gosme, M.; Hénault, C.; Schneider, A.; Cellier, P. Nitrous oxide emissions from crop rotations including wheat, oilseed rape and dry peas. Biogeosciences 2013, 10, 1787–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnke, G.; Zuber, S.; Pittelkow, C.; Nafziger, E.; Villamil, M. Long-term crop rotation and tillage effects on soil greenhouse gas emissions and crop production in Illinois, USA. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 261, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Liu, P.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X.; Wang, R.; Li, J. Long-term effects of optimized fertilization, tillage and crop rotation on soil fertility, crop yield and economic profit on the Loess Plateau. Eur. J. Agron. 2023, 143, 126731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Xiong, J.; Du, T.; Ju, X.; Gan, Y.; Li, S.; Xia, L.; Shen, Y.; Pacenka, S.; Steenhuis, T.; et al. Diversifying crop rotation increases food production, reduces net greenhouse gas emissions and improves soil health. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichern, F.; Eberhardt, E.; Mayer, J.; Joergensen, R.; Müller, T. Nitrogen rhizodeposition in agricultural crops: Methods, estimates and future prospects. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2008, 40, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guardia, G.; Tellez-Rio, A.; García-Marco, S.; Martin-Lammerding, D.; Tenorio, J.; Ibáñez, M.; Vallejo, A. Effect of tillage and crop (cereal versus legume) on greenhouse gas emissions and Global Warming Potential in a non-irrigated Mediterranean field. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2016, 221, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Navarro, V.; Zornoza, R.; Faz, Á.; Fernández, J. A comparative greenhouse gas emissions study of legume and non-legume crops grown using organic and conventional fertilizers. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 260, 108902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maucieri, C.; Zhang, Y.; McDaniel, M.; Borin, M.; Adams, M. Short-term effects of biochar and salinity on soil greenhouse gas emissions from a semi-arid Australian soil after re-wetting. Geoderma 2017, 307, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, L.; Butterbach-Bahl, K.; Kiese, R.; Murphy, D. Nitrous oxide fluxes from a grain–legume crop (narrow-leafed lupin) grown in a semiarid climate. Glob. Change Biol. 2011, 17, 1153–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Chu, J.; Nie, J.; Qu, X.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, A.; Yang, Y.; Pavinato, P.; Zeng, Z.; Zang, H. Legume-based crop diversification with optimal nitrogen fertilization benefits subsequent wheat yield and soil quality. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 374, 109171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paungfoo-Lonhienne, C.; Wang, W.; Yeoh, Y.; Halpin, N. Legume crop rotation suppressed nitrifying microbial community in a sugarcane cropping soil. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 16707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutenberg, L.; Krauss, K.; Qu, J.; Ahn, C.; Hogan, D.; Zhu, Z.; Xu, C. Carbon dioxide emissions and methane flux from forested wetland soils of the great dismal swamp, USA. Environ. Manag. 2019, 64, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subrahmaniam, H.; Picó, F.; Bataillon, T.; Salomonsen, C.; Glasius, M.; Ehlers, B. Natural variation in root exudate composition in the genetically structured Arabidopsis thaliana in the Iberian Peninsula. New Phytol. 2024, 245, 1437–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Plaza-Bonilla, D.; Coulter, J.; Kutcher, H.; Beckie, H.; Wang, L.; Floch, J.; Hamel, C.; Siddique, K.; Li, L.; et al. Diversifying crop rotations enhances agroecosystem services and resilience. Adv. Agron. 2022, 173, 299–335. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Ti, J.; Zou, J.; Wu, Y.; Rees, R.; Harrison, M.; Li, W.; Huang, W.; Hu, S.; Liu, K.; et al. Optimizing crop rotation increases soil carbon and reduces GHG emissions without sacrificing yields. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 342, 108220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernay, C.; Makowski, D.; Pelzer, E. Preceding cultivation of grain legumes increases cereal yields under low nitrogen input conditions. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2017, 16, 631–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, S.; Tan, J.; Li, L.; Miao, Y.; Wang, Y. Legumes can increase the yield of subsequent wheat with or without grain harvesting compared to Gramineae crops: A meta-analysis. Eur. J. Agron. 2023, 142, 126643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimonyo, V.; Snapp, S.; Chikowo, R. Grain legumes increase yield stability in maize based cropping systems. Crop Sci. 2019, 59, 1222–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyrard, C.; Mary, B.; Perrin, P.; Véricel, G.; Gréhan, E.; Justes, E.; Léonard, J. N2O emissions of low input cropping systems as affected by legume and cover crops use. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2016, 224, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regassa, H.; Elias, E.; Tekalign, M.; Legese, G. The nitrogen fertilizer replacement values of incorporated legumes residue to wheat on vertisols of the Ethiopian highlands. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacometti, C.; Mazzon, M.; Cavani, L.; Triberti, L.; Baldoni, G.; Ciavatta, C.; Marzadori, C. Rotation and fertilization effects on soil quality and yields in a long term field experiment. Agronomy 2021, 11, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, J.; Culman, S.; Logan, J.; Poffenbarger, H.; Demyan, M.; Grove, J.; Mallarino, A.; McGrath, J.; Ruark, M.; West, J. Improved soil biological health increases corn grain yield in N fertilized systems across the Corn Belt. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 3917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B. Are nitrogen fertilizers deleterious to soil health? Agronomy 2018, 8, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon-Miquel, G.; Reckling, M.; Lampurlanés, J.; Plaza-Bonilla, D. A win-win situation—Increasing protein production and reducing synthetic N fertilizer use by integrating soybean into irrigated Mediterranean cropping systems. Eur. J. Agron. 2023, 146, 126817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zou, J.; Huang, W.; Manevski, K.; Olesen, J.; Rees, R.; Hu, S.; Li, W.; Kersebaum, K.; Louarn, G.; et al. Farm-scale practical strategies to increase nitrogen use efficiency and reduce nitrogen footprint in crop production across the North China Plain. Field Crop Res. 2022, 283, 108526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shcherbak, I.; Millar, N.; Robertson, G. Global metaanalysis of the nonlinear response of soil nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions to fertilizer nitrogen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 9199–9204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanlauwe, B.; Bationo, A.; Chianu, J.; Giller, K.; Merckx, R.; Mokwunye, U.; Ohiokpehai, O.; Pypers, P.; Tabo, R.; Shepherd, K.; et al. Integrated soil fertility management—Operational definition and consequences for implementation and dissemination. Outlook Agric. 2010, 39, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Pol, L.; Robertson, A.; Schipanski, M.; Calderon, F.; Wallenstein, M.; Cotrufo, M. Addressing the soil carbon dilemma: Legumes in intensified rotations regenerate soil carbon while maintaining yields in semi-arid dryland wheat farms. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2022, 330, 107906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, A.; van den Brand, G.; Vanlauwe, B.; Giller, K. Sustainable intensification through rotations with grain legumes in Sub-Saharan Africa: A review. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 261, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Season | Sequence | Crop | Planting Date | N Fertilization | Harvest Date | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Type | kg N ha−1 | |||||

| GS1 | WM0 | maize | 13 June | 25 September | |||

| WM330 | maize | 11 June | Basal | 120 | |||

| 15 August | Top dressing | 60 | |||||

| WS0 | soybean | ||||||

| WS200 | soybean | 11 June | Basal | 50 | |||

| WSM0 | soybean | ||||||

| WSM265 | soybean | 11 June | Basal | 50 | |||

| GS2 | WM0 | wheat | 19 October | 26 May | |||

| WM330 | wheat | 17 October | Basal | 100 | |||

| 25 March | Top dressing | 50 | |||||

| WS0 | wheat | ||||||

| WS200 | wheat | 17 October | Basal | 100 | |||

| 25 March | Top dressing | 50 | |||||

| WSM0 | wheat | ||||||

| WSM265 | wheat | 17 October | Basal | 100 | |||

| 25March | Top dressing | 50 | |||||

| GS3 | WM0 | maize | 15 June | 20 September | |||

| WM330 | maize | 13 June | Basal | 120 | |||

| 9 August | Top dressing | 60 | |||||

| WS0 | soybean | ||||||

| WS200 | soybean | 13 June | Basal | 50 | |||

| WSM0 | maize | ||||||

| WSM265 | maize | 13 June | Basal | 120 | |||

| 9 August | Top dressing | 60 | |||||

| GS4 | WM0 | wheat | 22 October | 27 May | |||

| WM330 | wheat | 20 October | Basal | 100 | |||

| 19 March | Top dressing | 50 | |||||

| WS0 | wheat | ||||||

| WS200 | wheat | 20 October | Basal | 100 | |||

| 19 March | Top dressing | 50 | |||||

| WSM0 | wheat | ||||||

| WSM265 | wheat | 20 October | Basal | 100 | |||

| 19 March | Top dressing | 50 | |||||

| pH | NH4+-N mg kg−1 | NO3−-N mg kg−1 | DOC g kg−1 | TN g kg−1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WM0 | 6.63 ± 0.09 a | 14.03 ± 1.07 b | 51.24 ± 1.89 b | 13.43 ± 0.12 b | 1.58 ± 0.04 c |

| WM330 | 6.33 ± 0.03 b | 18.73 ± 0.60 a | 60.16 ± 1.74 a | 14.27 ± 0.20 a | 1.87 ± 0.06 a |

| WS0 | 6.57 ± 0.07 ab | 15.25 ± 1.08 ab | 50.38 ± 1.87 b | 13.50 ± 0.17 b | 1.73 ± 0.03 ab |

| WS200 | 6.40 ± 0.06 ab | 16.97 ± 0.74 ab | 56.37 ± 1.98 ab | 13.93 ± 0.09 ab | 1.81 ± 0.01 ab |

| WSM0 | 6.53 ± 0.03 ab | 14.50 ± 0.41 b | 52.35 ± 1.71 ab | 13.63 ± 0.09 ab | 1.68 ± 0.02 bc |

| WSM265 | 6.40 ± 0.06 ab | 17.57 ± 0.57 ab | 57.76 ± 1.27 ab | 14.07 ± 0.15 ab | 1.84 ± 0.01 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lin, F.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y. Legume-Based Rotations Enhance Ecosystem Sustainability in the North China Plain: Trade-Offs Between Greenhouse Gas Mitigation, Soil Carbon Sequestration, and Economic Viability. Agriculture 2026, 16, 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010116

Lin F, Liu Y, Zhang L, Zhang Y. Legume-Based Rotations Enhance Ecosystem Sustainability in the North China Plain: Trade-Offs Between Greenhouse Gas Mitigation, Soil Carbon Sequestration, and Economic Viability. Agriculture. 2026; 16(1):116. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010116

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Feng, Yinzhan Liu, Li Zhang, and Yaojun Zhang. 2026. "Legume-Based Rotations Enhance Ecosystem Sustainability in the North China Plain: Trade-Offs Between Greenhouse Gas Mitigation, Soil Carbon Sequestration, and Economic Viability" Agriculture 16, no. 1: 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010116

APA StyleLin, F., Liu, Y., Zhang, L., & Zhang, Y. (2026). Legume-Based Rotations Enhance Ecosystem Sustainability in the North China Plain: Trade-Offs Between Greenhouse Gas Mitigation, Soil Carbon Sequestration, and Economic Viability. Agriculture, 16(1), 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010116