Abstract

Risk management and resilience of agriculture are among the most important issues in the ongoing discussion on the shape of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). Farming systems face various risks that increase their vulnerability, which necessitates the strengthening of their resilience. This raises critical questions whether CAP policies adequately support the resilience of farming systems in addressing these challenges. The study investigates the resilience of the Polish fruit and vegetable farming system within the context of the CAP. Employing a mixed-methods approach that includes interviews and stakeholder workshops, the research identifies critical risks such as market volatility, climate change, labor shortages, or international competition. The study reveals that while farmers adopt various coping strategies, existing CAP measures predominantly support robustness, often neglecting adaptability and transformability, which are essential for addressing long-term risks. Stakeholder feedback highlights bureaucratic inefficiencies, limited access to resources for innovation, and an overemphasis on short-term interventions. Recommendations emphasize the need for policy adjustments to foster long-term adaptability through enhanced vertical and horizontal integration, support for innovation, and knowledge transfer. Under future scenarios, policy priorities vary but consistently call for resilience-focused reforms. These findings underscore the benefits of integrating resilience-thinking frameworks into agricultural policy to enable sustainable development and competitiveness of farming systems.

Keywords:

agriculture; resilience; agricultural policy; CAP reform; horticulture; sustainability; fruits; vegetables 1. Introduction

Risk management and resilience of agriculture are among the most important issues in the ongoing discussion on the shape of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). In the present article, the resilience of European farming systems is investigated. Farming system is defined as system linking farms with other actors influenced by the farms and vice versa. Those farming systems face a broad scope of risks and challenges, especially of economic, environmental, social, and institutional character [1]. The relative relevance of these aspects appears to have evolved recently, and environmental concerns are becoming more significant. Research results indicate that while the CAP post-2020 can enhance environmental performance, it imposes financial and organizational burdens on farms [2,3]. However, market, policy, and technological development may all be equally important [4]. Those external stresses change the context of farming system operations and increase the level of the vulnerability of these systems.

Since disturbances and pressures have a broad impact on farming systems, improving resilience entails assisting farms and farming systems in managing to be immune as much as possible. That requires from farming systems, on one side, the ability to responding to various disruptions, and on the other side, maintaining vital functions of the farming system. Among those functions are the following: agricultural production, providing jobs and generating revenue, as well as the preservation of rural regions, ecosystem services, and biodiversity. These issues require addressing and answering the question of whether the current and planned designs of the CAP and other policies are capable of supporting the resilience of farming systems.

Resilience thinking may contribute to a better understanding of the interconnections and challenges of establishing sustainable food production, diversified agro-ecosystems, and vibrant rural regions [5]. Resilience theory originates from ecology and systems theory, but recently has been used in economics, political science, and management theories [6]. Resilience theory provides an interdisciplinary framework to investigate the ability of complex socio-ecological systems to cope with changing environments [7]. The proposed research uses this approach and contributes to the ongoing discourse related to the future of the CAP and its influence on the resilience of farming systems, by analyzing this influence in the context of its capacities of robustness, adaptability, or transformability and their 12 main characteristics.

The definition of resilience in the present study is based on the framework developed by Meuwissen et al. [8]. Resilience is defined as the ability to retain system functions in the face of increasingly complex and accumulating economic, social, environmental, and institutional shocks and stressors through robustness, adaptability, and transformability. Robustness is the farming system’s ability to withstand stresses and (un)expected shocks [9]. Adaptability is defined as the capacity to modify the composition of inputs, production, marketing, and risk management in response to shocks and stressors without affecting the structure and feedback mechanisms of the farming system [10]. Transformability is the ability to substantially transform the internal structure and feed-back mechanisms of the farming system in response to major shocks or long-term stress that make business as usual untenable [11].

The scientific problem which the presented research aimed to solve is to assess the influence of the European Union policies on the resilience of Polish farming systems, in terms of robustness, adaptability, and transformability, based on the fruit and vegetable farming system as an example.

The abovementioned main goal may be broken down into five specific research questions that will serve as a guideline for this study:

- What are the main challenges for the examined farming system?

- How do the actors within the farming system cope with those challenges?

- How do the main actors perceive the strengths and weaknesses of the CAP 2014–2020 in Poland in terms of robustness, adaptability, and transformability?

- What policy mix would be the most desirable for stakeholders in different future scenarios for farming in the European Union (EU)?

The marginal contribution of this paper lies in its novel integration of resilience theory into the assessment of CAP impacts on Polish farming systems, particularly in the fruit and vegetable system. The study addresses a critical gap by highlighting the relative neglect of adaptability and transformability in CAP implementation, aligning with recent findings that stress the importance of long-term resilience strategies [12]. By focusing on less-supported farming systems—specifically, fruit and vegetable production in Poland—this study fills a gap in the literature, which has often centered on more intensively subsidized sectors such as dairy or cereal farming [13]. Unlike many analyses that treat the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) in general terms [14], the present research examines how CAP measures interact with local realities of a region historically receiving fewer subsidies, thus offering new insights into the policy’s shortcomings and potential. In doing so, it contributes to practice by highlighting the practical needs of smaller and medium-sized fruit and vegetable producers who rely largely on internal resources to cope with market, environmental, and social risks.

1.1. Literature Review

To formulate research hypotheses, a literature review and an appraisal of the state of scientific knowledge in the field of resilience of farming systems in Poland have been conducted. Resilience theory emphasizes changes and uncertainty, and stresses the role of the capacity of the system to adapt and transform as important aspects in reducing vulnerability [6,15,16]. Policy can enhance resilience of farms in three different capabilities—robustness, adaptability, and transformability [8]. However, observation of the CAP development shows that more CAP measures and budget allocation were devoted to reactive rather than proactive courses of action. Farms and their robustness were a major focus of resilience measures, but other solutions and possibilities were overlooked [17]. For example, research suggests that enhancing social capital and learning among farmers can improve adaptability and transformability, contributing to overall resilience, and policies should focus more on fostering these elements [18]. The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) of the European Union is structured around two main pillars, each serving distinct purposes and mechanisms to support agriculture and rural development. Pillar I includes direct payments and market measures [19], while Pillar II is dedicated to rural development and is implemented through multi-annual rural development programs [20]. The transfer structure analysis for Poland suggests a shift in the ratio between funds obtained by Poland under the CAP’s Pillar I and Pillar II. While this ratio stood at 50:50 in the early years of Polish membership in the EU, it changed to 60:40 with the predominance of Pillar I (direct payments) for the period 2014–2020, and a ratio of around 80:20 for the years 2023–2027 [21]. This is the consequence of a decision made by Poland as part of the flexibility given to member states in terms of transferring funds between the pillars. Poland was among a small group of five new member states that decided to move funds from Pillar II (funds allocated for rural development) to Pillar I [22]. There was a sharp decline in funds for the development of rural areas (Pillar II of the CAP) between the respective periods of 2007–2013 and 2014–2020, which was due to a transfer of 25% from Pillar II to Pillar I [23]. Poland was the only country that decided to shift the maximum allowed amount of 25% of the value of funds allocated to rural development to Pillar I (direct support system). The vast majority of countries transferred funds from Pillar I to Pillar II [22]. Such division of funds limits resources for important investments related to the modernization of agriculture and the competitiveness of farms. Compensations and decoupled measures were significantly more supported than investments. Coping with problems, and continuing and withstanding farming, even in unfavorable conditions, was more strongly supported than adapting for new forms of farming or transforming farming into other activities, such as tourism. In the years 2004–2020, only about 0.9% of the funds of RDPs were allocated to knowledge transfer and innovation [24]. In Poland, more support was directed to support “equality” rather than “efficiency” of the CAP measures [25].

At the same time, pressure of the European Union for pro-environmental activities in agriculture requires adaptability, such as a transition towards lower-input farming practices [26]. Some studies suggest that organic practices in fruit and vegetable farming have the potential to provide high-quality crops in quantities comparable to resource-intensive practices [27]. However, the transitions to organic farming requires additional resources and the role of subsidies is the most important in the transition period, when it is not yet possible to obtain additional income from selling organic products [28].

The adaptability of the fruit and vegetable farming system is essential to enhance the competitive position of Polish fruits and vegetables in foreign markets. In Poland, apple production is particularly significant, accounting for around 80% of the fruit harvest [29]. However, the yield of Polish apple orchards is low compared to the most productive countries. According to Kraciński and Wicki [30], between 2015 and 2027, the average yield was 19 t/ha, compared to an average harvest of 40–50 t/ha in countries like New Zealand, Italy, or Chile. At the same time, the harvest of Polish apples increased by 55% between 2005 and 2008, as well as 2015 and 2017, as a result of improved technology and greater intensification of production, which is a sign of progress in adaptability. The CAP’s focus on environmental sustainability and quality standards can help Polish producers improve their competitiveness. However, meeting these standards requires significant investment and adaptation, which can be challenging for smaller farms [31].

The conducted literature studies and the recognition of the state of scientific knowledge in the field of resilience of farming systems in Poland allowed the formulation of the following research hypothesis:

- -

- The current CAP’s support for adaptability of the fruit and vegetable farming system does not answer the needs of the system.

In order to empirically verify the hypothesis, it is necessary to assess the needs of the farming system and the support for different capacities of resilience (robustness, adaptability, and transformability) offered by the CAP. This hypothesis was tested using a problem-based case study method. As the hypothesis refers to the system and its stakeholders, the bottom-up approach was applied to explore their experiences [32]. Triangulation was used for assuring validity of the research and a comprehensive understanding of the phenomena [33,34]. The data were collected via in-depth interviews, focus groups, and a stakeholder workshop.

1.2. The Context and Rationale for the Lubelskie Fruit and Vegetable Farming Case

While some farming systems, such as dairy, receive relatively more support than others from the CAP funds, little is known about how beneficial the CAP is for the less-supported systems, e.g., fruit and vegetable farming. It is also important to understand how these systems respond to the policy, considering that EU farmers are known for their distinctive diversity [35]. Fruit and vegetable production is one of Poland’s most significant agricultural production sectors. Even though it only covers 635,000 ha, or 4.4 percent of arable land in good condition [36], fruit and vegetable production accounted for more than 40% of overall crop cultivation in 2019 [37]. The fruit and vegetable farming system consists mainly of small and medium-sized farms and is one of the farming systems benefitting least from the CAP in Poland, despite the political agreement existing on the EU level of reducing subsidies to major farm operators in favor of small farmers, and it continues in the CAP post-2020 [38]. The Lubelskie region’s fruit and vegetable farming system was chosen for the case study because it has historically received less CAP funding. As a result, it was not as policy-biased as many other farming systems. The examined farming system needed to deal with challenges to a large extent using its own capacities and resources; thus, stakeholders within the farming system understand their needs while coping with risks and capturing opportunities, and can provide input in measures that would assist in this process other than direct subsidies. It is seen as a valuable point of view that has been comparatively less impacted by agricultural policy in the past. In the Lubelskie region, 99.78% of arable land belongs to individual family farms [39].

The fruit and vegetable farming system is exposed to numerous risks. The vulnerability to economic risks is related to declining prices due to the Russian embargo, variations in prices, and a lack of labor for seasonal and labor-intensive work [40]. In 2014, the Russian Federation put an embargo on the Polish agricultural sector. As a result, the import of (among others) Polish fruits and vegetables was suspended. This particularly affected the market for some products, e.g., apples, whose export level was highly dependent on the Russian market [41]. The embargo also resulted in a decrease in the volume of Polish fruit and vegetable exports to the countries of the Commonwealth of Independent States [42]. Additionally, the embargo affected the prices of fruits and vegetables. Also, other factors, such as the Single European Market or price changes on the world market, influence fruit and vegetable prices in Poland. The prices are subject to seasonal supply fluctuations also, mostly due to the fruits’ sensitivity to unfavorable agro-meteorological conditions, which contribute to crop failure [43]. In the years 2008–2016, price volatility for fruits amounted to 22.3% and in the case of vegetables, it was at the level of 13.1% [44]. Another factor is the fragmentation of production, which weakens the position of individual growers in the food supply chain and reduces their influence on prices. Prices are largely dictated by the fruit processing industry and other large purchasers [45]. Poor agricultural business organization in Poland is one of the most serious issues affecting the farming industry [46].

Vulnerability to environmental risks is related to the increasing incidence of extreme weather phenomena, such as hail, freeze, drought, and to hydrological instability, infestation of trees by pests and fungal diseases. For example, floods in 2010 and May frosts in 2011 caused the rapid price increase in fruits and vegetables [44]. At the same time, Poland is one of the countries with the smallest water resources per capita and, consequently, water shortage is expected to have far-reaching consequences on agriculture [47]. However, a decrease is projected for the potential soil moisture deficit by the end of the century [48].

Vulnerability to social risk relates to changes in the preferences of consumers [49,50,51]. Fruits represent a negligible part in the pattern of consumption, and with low incomes, the spending on them can be limited. However, despite the fact that the EU policy measures taken to promote healthy food are not effective [52], the fruit and vegetable sector in Poland was defined by its high consumption growth dynamics in the years 2005-2018 [53]. During the pandemic, the long-observed interest in a healthy diet, which was primarily demonstrated by a rise in demand for fruit and vegetables, increased [54]. Another key factor forming the volume of the consumed fruit is their prices, which influence the periodical changes in demand for particular species. These changes are partly attributed to variations in domestic production which are highly dependent on atmospheric conditions [55]. Another factor influencing the resilience of the system is that, especially in the FADN region of Mazovia and Podlasie (Lubelskie is a part of this Farm Accountancy Data Network region), there is the lowest crop insurance uptake in the country [56].

2. Materials and Methods

While a policy may be intended to enhance resilience of farming systems, its practical consequences may vary, depending on the features of farming systems, the local environment, and the perceptions of relevant stakeholders [57]. Stakeholder engagement can help with assessing the effects of policies at the regional level, as well as identifying stakeholder perceptions and reactions to specific governance frameworks [58]. Understanding how adaptation to complex and dynamic environment and policy demands is dealt with by stakeholders is essential for sustaining a viable and resilient agricultural industry, both economically and ecologically [59].

The assessment was based on the bottom-up approach to policy research [32], as the actor perspective is useful for identifying relevant policies and their consequences [60]. Through the realistic experiences of stakeholders in and around farming systems, the bottom-up research enabled an examination of interrelations across policies and their impact on resilience. However, the bottom-up method is not without limitations. Because it relies on subjective viewpoints, findings may be influenced by personal biases, selective recall, or strategic responses from more vocal participants, potentially skewing the data. Additionally, participants with stronger incentives or greater availability could have been over-represented, restricting the generalizability of results [61]. To mitigate these risks, we employed triangulation through in-depth interviews, stakeholder workshops, and document analysis, cross-validating data to identify consistent themes and reduce the impact of individual biases [62]. Despite these measures, qualitative approaches inherently limit broad generalizations; future research could benefit from randomized samples to further refine and validate these findings.

The study examines how policy frameworks affect the robustness, adaptability, and transformability of the farming system, based on the conceptualization of Meuwissen et al. [8]. It also addresses the case of non-resilience, which refers to a farming system experiencing a decline in its basic public and private functions. Resilience, as a potential, cannot be directly observed; therefore, in the presented study it is examined in retrospect, focusing on the responses of the farming system to changes and challenges in recent years (after 2004—Polish accession to the European Union), as viewed by the relevant stakeholders.

The research investigates stakeholder perspectives on policy impacts rather than determining causal relationships [63,64]. The focus of the research was not exclusive to farmers, but included all stakeholders who had a direct impact on farmers’ behavior, such as advisors, family members, organizations of farmers, tenants, suppliers, etc. As a result, the study was of an exploratory character.

In this study, in-depth interviews allowed for the nuanced exploration of farmers’ and other stakeholders’ experiences, revealing how they perceive and respond to policy-driven opportunities and constraints [61]. Meanwhile, stakeholder workshops served as a platform for interactive discussions, consensus-building, and scenario exploration, thereby enriching the data with collective insights and facilitating the co-creation of knowledge among participants. By integrating these methods, the research aligns with contemporary calls to triangulate data sources for increased validity, capturing both individual and group-level dynamics and improving the applicability of findings to policy adjustments [62]. Consequently, the mixed-methods design was well-suited to identifying critical risks, evaluating how CAP measures influence different resilience capacities, and generating actionable recommendations for long-term agricultural sustainability and competitiveness.

2.1. In-Depth Interviews—Materials and Methods

In four cases, the impact of policy configurations on the resilience of farming system was investigated. These cases were analyzed using 20 in-depth interviews with key actors, as well as document analysis.

Semi-structured interviews were used to explore stakeholder perceptions and experiences in depth while maintaining a systematic yet flexible approach to data collection [65]. This method is widely used in qualitative research because it allows investigators to probe complex themes while giving participants the freedom to introduce new insights [61]. In determining the sample size, we followed the principle of data saturation, which is reached when additional interviews no longer yield substantially new information [66]. Recent guidelines suggest that saturation can often be achieved with between 12 and 20 interviews in relatively homogeneous populations [67], although the final number may vary depending on the study’s specific goals and the diversity of participants. Consequently, 20 in-depth interviews were deemed sufficient for capturing a broad spectrum of views within the fruit and vegetable farming system in the Lubelskie region, especially given its relatively unified context of farm types and the focused nature of our inquiry. This approach ensures a depth of understanding that is appropriate for exploratory research on policy impacts and stakeholder perspectives, even if it does not claim statistical representativeness [61]. The farming system cases were all located in the Lubelskie region; however, the administrative region is not considered as delimiting for the farming system. The selection of cases from a single administrative region ensured a consistent policy mix, minimizing variations that could arise from different regional programs and their diverse outcomes.

Four regional farming system cases were to be selected which represented robustness, adaptability, transformability, or decline. The aim was to ensure variety in terms of the stability and change of activities and functions, not to place cases into theoretical sub-categories, since farming system cases demonstrate characteristics of different capacities of resilience.

In this study, purposeful sampling was utilized. Participants for in-depth semi-structured interviews were identified through a combination of criterion sampling and chain-referral sampling. This ensured the employment of maximum variation to describe multiple perspectives about the cases and representation of various stakeholders directly or indirectly influencing the fruit and vegetable system [68]. The selection of the research sample was made after consultations with the employees of the Lublin Agricultural Advisory Center and the National Union of Fruit and Vegetable Producer Groups.

Potential respondents were initially contacted by phone (they were previously informed by advisers of the abovementioned organizations about the possibility of us choosing their farms for research). After telephone conversations with potential respondents, farms that met the conditions of robustness, adaptability, transformability, or declining to the highest extent were selected. After that, in-depth interviews were conducted.

The robustness case was carried out at a farm with both fruit (22 ha) and vegetable (10 ha) production, which contained of 22 ha of own land and 10 ha of rented land. The adaptability case was based on a farm of 5.39 ha which was focused on vegetable and cereal production, with plans of starting fruit production (plum orchard). It was a family farm, characterized by a low class of land. The owners adapted to the market demands by reducing the amount of fertilizers, etc., but they did not plan to start organic farming, due to the costs of certifications. The transformability case was observed at a farm of 25 ha, focused on vegetables and cereals, co-owned by a father and his son. The wife of the farmer worked outside of agriculture. The farmers changed the farming practices into organic. The owners also rented rooms for tourists. Farming accounts for about half of the income, and agrotourism for the other half. The decline case was exemplified by a farm of 24 ha, focused on fruit and cereal production, however only 14.5 ha was cultivated by the owner and the remaining part was rented to another farmer. Because the owner was 72 years old and had no successor, he started downscaling the production in recent years and did not conduct investments in the farm. The owner of the farm is also the owner of a shop.

In-depth interviews were the most important part of the bottom-up analysis. During interviews with selected farmers, the guidelines from the protocol for bottom-up policy analysis [69] were used. All interviews were transcribed. To select other respondents, chain-referral sampling was used [70].

A semi-structured in-depth interview approach was used, because the aim was not to direct respondents into specific responses (e.g., specific policies), but rather to engage in their perception of policy effects. Nevertheless, the interviews always discussed issues related to the background and assessment of the condition and development prospects of the fruit and vegetable system; drivers of behaviors and relations between different stakeholders; ways of obtaining information and learning within the system; the most important risks and challenges to which the system is exposed; ways of dealing with these risks and challenges by actors in the system; assessment of the case study farms relevant to the respondent (respondents were not always referring to a given farm, but they were characterizing problems of the whole group of similar farms); resilience; the policies affecting the farming system; and access to knowledge, capital, social networks, markets, insurance, and other resources. The interviews began with an explanation of the study background, data use, and details regarding the promise of personal privacy in data analysis and reporting.

In total, there were twenty in-depth interviews performed between January and March 2020. Among the respondents, there were nine farmers, including two involved in ecological farming, four advisors, two sons of farmers, two public administration officials, one land tenant, one representative of the Local Action Group, and one input supplier.

The coding took place with the usage of the qualitative data analysis software ATLAS.ti, (version 9) which is a popular software for analyzing data collected from interviews, focus groups, documents, field observations, and open-ended survey questions [71]. The coding was conducted in two rounds—the first round focused on the challenges of the system and the ways of coping with challenges, policies affectingthe system, as well as resources and networks used by the respondents to learn about policies. The approach to develop codes for this round was a combination of theory- and data-driven approaches [72]. An initial set of codes was supplemented by the case-specific codes which proved to be relevant during the interviews and consisted of 108 codes.

The second round of coding focused on the influence of policies on the resilience of the farming system and was developed using a deductive approach. It allowed us to indicate if these policies enable or constrain robustness, adaptability, and transformability. It included coding on the ordinal scale 0–5 to indicate the level of enabling resilience capacities and their characteristics. During this round of coding, it was assessed which resilience capacities were concerned and whether the policy had an enabling or restricting impact based on the experiences shared by participants during interviews. Furthermore, this round allowed to code experienced inconsistencies inside and between policies, as well as perceived inconsistencies between policy objectives, instruments, and implementation. This round consisted of 20 codes.

The stakeholders’ check (proofing) was organized with eight participants, including two representatives of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, a farmer, one representative of the Institute of Agricultural and Food Economics—National Research Institute, two experts in fruit and vegetable farming, and two experts in the Common Agricultural Policy.

2.2. Workshop—Materials and Methods

The second part of the research included a workshop on the CAP recommendations. The meeting took place in Warsaw, Poland, at the Institute of Rural and Agricultural Development, Polish Academy of Sciences in March 2020. There were eleven stakeholders participating in the meeting and their roles were as follows: two policymakers, two advisors, two farmers, one representative of a farm organization, one representative of regional self-government, and three scientists/policy researchers. In more detail, they represented the following institutions: one from the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, one from the Agency for Restructuring and Modernization of Agriculture, one from the Mazowiecki Agricultural Advisory Center with headquarters in Warsaw, one from the Department of Agriculture and Rural Development of the Marshal’s Office of the Mazowieckie Voivodeship, one from the Institute of Agricultural and Food Economics—National Research Institute, one from the Polish Chamber of Regional and Local Product, one from the Agricultural Advisory Center in Brwinów, one from the Faculty of Economic Sciences, Warsaw University of Life Sciences, one from the Faculty of Economic Sciences, University of Warsaw, and two were farmers. The participants were provided with accompanying materials (in Polish), which aimed to help them in the discussion: 4 pages with main concepts and definitions, including scenarios, and 3 pages with Resilience Assessment Tool (ResAT) [73] wheels to fill in during the workshop.

The workshop started with an introduction presenting the goals of the meeting. Then, the participants presented themselves to each other. After that, the concepts of resilience and the farming system were introduced. The three capacities of resilience and the characteristics of policies supporting those capacities were described. The results of in-depth interviews with stakeholders were shortly presented. At the end of the introduction, the participants had an opportunity to ask questions, to ensure understanding.

After the introduction, the workshop carried on in two rounds. The first round was aimed at creating generic policy recommendations on enhancing three resilience capacities: robustness, adaptability, and transformability. This round was based on structured discussion answering the questions what policies or associated actions are needed to enhance each capacity and how this could be achieved. The first round ended with participants filling the Resilience Assessment Tool wheel for the Polish fruit and vegetable farming system in a future status quo scenario using the scale of 1–5.

In the second round, the focus was put on who and at what level (EU, national, or regional) should introduce the measure, what precisely needs to be done, how those measures can enhance particular resilience capacities and how they can be implemented. The suggestions were collected on a whiteboard, divided up per resilience capacity, governance level, and time frame: short-term—up to one year; mid-term—1–5 years; and long-term—>5 years. At the end of the round, the participants voted on which actions they considered the most important.

In the third round of the workshop, stakeholders assessed the desired mix of policies under two different scenarios for EU farming. The scenarios were based on the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) developed by O’Neil et al. [74], as these scenarios have been used and quantified in several projects [75,76,77]. SSPs are defined based on two critical uncertainties—socioeconomic challenges for adaptation and socioeconomic challenges for mitigation. Mathijs et al. [78] adjusted the available SSP narratives, which were developed for a whole global economy, to narratives significant for the EU farming systems, using extensive literature review on food consumer trends, complementing the narratives with insight from the EU scenario exercises [79,80,81] and using system thinking to increase coherence of the scenarios. They were used in this research as baselines for future scenarios so that stakeholders could more easily imagine a later development under which the farming system may operate in the future. It was important to use the precise future pathways, because they were relatively formal and based on possible developments, which nevertheless differ depending on the assumptions. Therefore, from the five scenarios (see Table 1), two were chosen for the workshop, which were the most different from each other in terms of policy—the most protectionist (SSP 3) and the most liberal scenario (SSP 5). Hence, the stakeholders had to imagine two different backgrounds in which the policies could operate in the future, having information about the key economic variables describing this future (see Table 1). Introducing additional scenarios could risk confusing participants and limiting the depth of discussion, given the time constraints of the workshop.

Table 1.

An overview of the farming system description for the 5 EU-Agri-SSP scenarios.

The third round of the workshop ended with participants filling the ResAT wheels for both scenarios. After that a short summing up of the meeting took place.

3. Results

Results obtained in the bottom-up analysis covered challenges experienced by the farming system, ways of coping with those challenges and utilizing opportunities as recognized by stakeholders. The perceived role of policies on the resilience of the fruit and vegetable farming system was examined. Additionally, data on the scope of social networks and contacts to discuss policies, ways to access information and learn about policies, and the availability of capital to manage challenges were collected.

3.1. The Challenges of the System

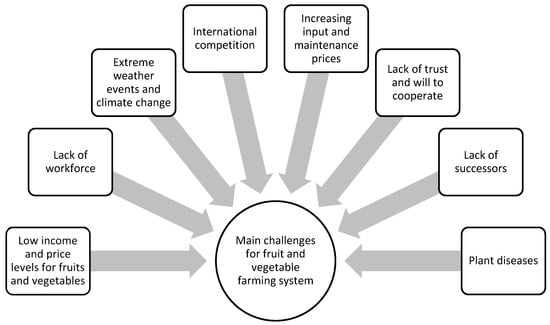

Results demonstrate that the fruit and vegetable farming system in Poland faces multiple challenges, which can hinder the resilience of the system (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The main challenges for the fruit and vegetable farming system in the Lubelskie region, according to stakeholders. Source: own study.

Income and fair prices were considered by around three-quarters of the respondents as a very important challenge—“First and foremost—concerns about prices”. The respondents pointed out that the prices of their products are not rising. Also, the fluctuations of prices are a challenge.

Another very important challenge is the lack of a workforce, which is increasingly problematic in recent years. The problem can be so serious that farmers resign from particular crops because of this issue. The problem seems to be especially serious in vegetable production. One of the reasons for this challenge, according to the respondents, is the emigration of the Polish workforce abroad, where the salaries are higher. Another indicated factor is the aging of the population.

Other main risks are weather events and climate change. The main problem is drought. However, other weather events can also be problematic—“There was a frost last year. It caused significant freezing”. A related challenge is the water supply.

Many respondents indicated challenges related to market and competition. One of the problems is low prices in years when there are a lot of products on the market. The international competition is increasing the pressure on producers. It is also difficult for farmers to supply big supermarket chains.

Increasing input and maintenance prices brings other challenges. Respondents indicate that the relation between costs and income is less and less profitable. The cost of labor is, for many respondents, also very high. In addition, costs of insurances are considered very high.

The cooperation, both horizontal and vertical, is problematic due to a lack of trust and will to cooperate. Respondents suggest that it might be related to mentality: “Maybe it stems from the mentality that it’s better if your neighbor is worse off. Heaven forbid, if he is better off, then he becomes an enemy. There is too little exchange between neighbors”. They also point out the lack of local leaders.

Another challenge for some respondents is the farm succession. The paradox was noted where the farmers who invested in the education of their children currently have problems with farm succession because of that.

Respondents also point out the challenge of plant diseases—“The pressure from pests and plant diseases is also considerable”. Some farmers had, in the past, problems with obtaining plant protection products, which put their crops at risk.

3.2. Resilience-Enhancing Strategies of Farmers Within the System

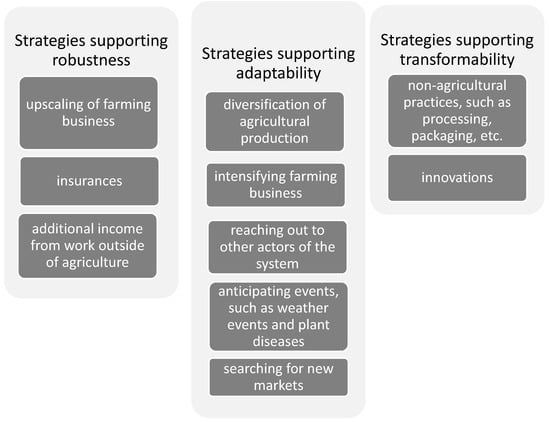

There are multiple ways for farmers and the farming system to cope with the mentioned risks and developments, as well as to capture opportunities (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The main strategies supporting resilience performed by farmers within the fruit and vegetable farming system in the Lubelskie region, according to respondents. Source: own study.

Many respondents indicate the diversification, especially of non-agricultural practices, as the important strategy. Notably, processing and packaging was considered an important activity; however, other means of diversification are also used—“An additional source of income is agritourism, such as renting rooms”. Diversification of agricultural practices is also used. It is common to combine fruit and vegetable production. One of the advantages of diversification is the possibility of collecting crops at different times, which diminishes the number of workers needed at one particular time. Farmers also combine fruit and vegetable farming with cereal cultivation.

Another strategy is to intensify farming business. It is used to cope with the lack of a workforce—“Farmers have greater access to the machinery parks and appropriate machines that replace manual work”. It plays also an important role in coping with draught. Both conventional and organic farming are using intensification. Respondents also pointed out the importance of the facilities to store the products.

Reaching out to farming system actors is another way to cope with challenges—“The future lies in group actions”. Being part of a producer group is helping farmers to sell their product. Cooperating with other farmers can be a way to deal with the lack of a workforce. Cooperation also allows the sharing of knowledge. Cooperation with family members helps to ensure the succession of the farm.

Upscaling of farming business is a strategy used by many farmers. It can be related to buying or renting land, or to making other investments in machines or facilities—“We built the greenhouse ourselves”. Respondents see the importance of anticipating events, especially in relation to weather events and plant diseases.

The important strategy is searching for new markets to sell the products. Some of them search for international markets—“Cauliflowers and broccoli are selling exceptionally well overseas. We have excellent customers who pay premium prices, significantly higher than those in Poland”. Others decide to sell in retail. There are also initiatives of creating a brand.

Respondents also indicated innovations as a strategy to cope with challenges.

Many respondents indicate that additional income helps to deal with challenges—“Few people can survive by solely farming, because they won’t survive. All our neighbors have additional jobs and treat work in agriculture as a supplementary activity”. Some farmers travel abroad for work.

Taking out insurances is a strategy used by some farmers, although the prices are considered very high. Therefore, some farmers insure just part of their business. However, others do not take out any insurance, in some cases because of negative experience in the past—“We had insurance for 15 years, maybe more, but stopped insuring some time ago. There was a hailstorm, and we did not receive any compensation”.

3.3. The Influence of Policies on Resilience

The policy that respondents most often indicated as influencing the farming system was investment in physical assets within Pillar II. Some respondents had already used these funds multiple times—“As part of our modernization efforts, we have already completed two projects and have just signed a contract for a third one”. However, some respondents indicated the lack of flexibility of this instrument, which is problematic for them. Another problem is the requirement of increasing production or acreage, mostly due to a lack of land available for purchase. Respondents also negatively perceive the extensive controlling system.

Knowledge transfer and advisory services were considered important for the system. Many farmers indicated that they use the services of public advisors. However, some respondents complained about the excessively narrow scope of the advisory service, which are mostly focused on administrative issues—“I’ve always believed, and still do, that this advice has gone in the wrong direction. It used to be said, and it probably still is, that this consultancy is just an extension of the administration. Now, it only deals with administrative matters and does not provide enough support to farmers”.

Small farmer support within Pillar II was also indicated as an instrument which is important for the system. However, the regulations are considered too detailed, which makes it more difficult for farmers to use the funds in the most suitable way—“I want to buy a small tractor that can easily navigate orchards and crops, but I can’t. According to the official, this is not considered a typical agricultural machine, and I gave up because he didn’t approve it. I don’t understand this decision”.

Young farmer support is considered a means to increase the acreage, or make investments, although it does not affect the decision of young farmers to start working in agriculture. The support is considered too small to be significant.

Social security policy is considered by respondents as negatively affecting the availability of the labor force—“Now they have 500+ program, and there is no one to pick raspberries”. It is also considered a factor which stops small farmers from selling their lands.

Weather risk management was considered by respondents as inadequate. The insurance system is not considered reliable—“We do not take our insurance anymore because the costs are high and insurers are dishonest. This is another reason why I have not insured anything for many years”.

Respondents do not consider the basic payment scheme as especially important for the fruit and vegetable farming system. They rely more on Pillar II. Respondents do not support Pillar I. Many of them see it as a way to maintain the status quo, where the land is kept by small farmers just to obtain the payments—“Sometimes subsidies are important, but in this case, they are more damaging. A farmer with the right equipment can cultivate several times more land than he currently has, but the amount of available land is limited, creating a vicious cycle. In agriculture, there are many people who are not truly involved in farming, and these subsidies keep them in the system. They don’t sow or plow”.

Respondents suggested different changes to enhance the resilience of the farming system. A common suggestion was diminishing the bureaucracy. Respondents complained that the bureaucracy is so complicated that it is not possible to deal with the procedures by themselves—“I want to write such an application, but if I try to do it myself, I will never get it done. I have to go to a company or a friend who handles these things professionally and pay them, because that is how it works in Poland”. It is also a reason for delays in receiving funds, which is problematic.

Many respondents indicated that the policy should ensure sales of agricultural products. However, those respondents do not indicate how such a policy change should be executed.

Some respondents suggested that credits are a better solution than subsidies, because they require one to think through the projects and increase the chance of success of projects. Some indicated that the subsidies should be abolished altogether. Other respondents pointed out that it might be hard to encourage new entrants to agriculture without subsidies. It was also noted that the differences between policies in EU countries make it difficult to compete on the international market.

Other respondents suggested the increase in the support for group actions, to avoid the inefficient use of funds—“Support should be directed towards helping groups of small and large farmers, particularly through producer groups and cooperatives. For example, expensive equipment is often purchased by a farmer who cannot afford it, and it ends up being used for only a few hours a year. This equipment then sits idle for the rest of the time”.

The lack of clear national strategy for agriculture was considered a weak point of the policy—“Our national strategy should prioritize organic farming and high-quality food. These should be considered national assets that we can offer to the world”. Another suggestion was related to the time frame of actions, which is currently too short.

Respondents also noticed that the number of trainings is not sufficient and should be increased—“There is some training available, but there should be more”.

3.4. Summary of Stakeholder Proofing

The participants agreed with the main risks and challenges indicated by the respondents, related to income and fair prices, a lack of labor force, weather events and climate change, water supply, market and competition, input and maintenance prices, and cooperation with other farmers. The main discussion points related to the risks and challenges were also related to the market. It was pointed out that the Russian embargo was the reason for the shrinkage of the market. It was stressed that the Ministry does not plan to regulate the market, so the farmers cannot count on that type of risk management. It was also stated that farmers are afraid of overregulation, especially in organic farming. Another important challenge stressed by stakeholders was the problem with the insurance system, which is highly ineffective.

The main responses to challenges and risks indicated in in-depth interviews—namely the diversification of practices, intensifying of farming business, reaching out to farming systems actors, and upscaling of farming business—were considered by participants as very typical responses. Participants considered diversification as a good strategy, because specialization in one product is more difficult. It was stressed that the quality of production is very important, more important than quantity. The important point raised by stakeholders was that farmers have a demanding attitude and even young farmers often see themselves as victims of the market. However, it was also noted that the whole value chain is dominated by big capital. An important point was also that fruit and vegetable production have slightly different problems, for example, regarding the need of labor. The strategies that were lacking or not visible enough, according to participants, were professionalization of the profession of farmer, the obtaining of knowledge, branding, innovations, searching for one’s own niche, the use of agrotechnics to deal with droughts, and insurance.

The key point related to the policies influencing the resilience of the system was that the broad range of stakeholders are not included in the process of policy creation. The problem for farmers to meet the requirements of Rural Development Programme instruments, such as the requirement of 10% increase in production, was stressed. It was pointed out that there is a need for spatial development and improvement of the policy of land management. In addition, the insurance system needs reform, according to stakeholders. Participants considered the importance of increasing the flexibility of policy important, as well as rationality of regulations. More important should be the goal, not the separate actions. The important notion was that the direct payments are not as important for Polish fruit and vegetable farms as for other production types, because it consists of 14–15% of the income, compared to around 50% for many other production types. It was suggested that innovations should be mostly supported by Regional Development Funds, not the Rural Development Programme, which is already too complicated.

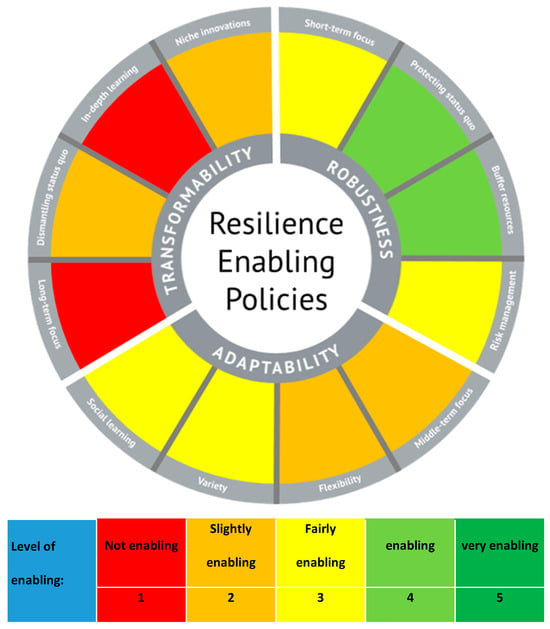

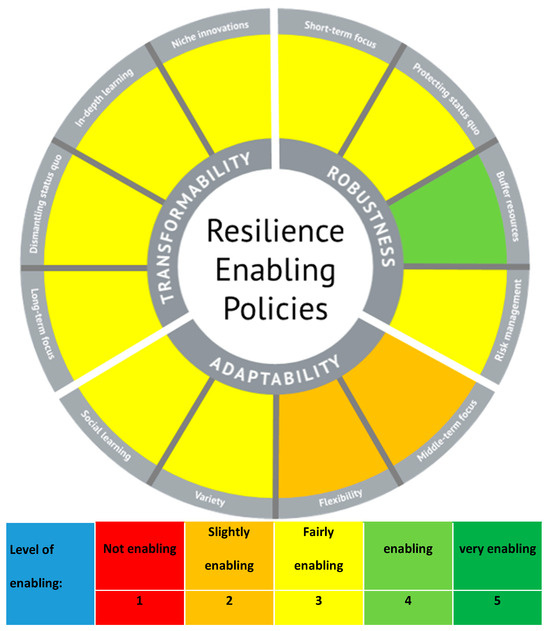

At the end of the meeting, the level of support for the robustness of the farming system was estimated by participants, on average, at the level of 2.86 (on a scale of 1–5), for adaptability it was 2.29 on average, and for transformability—1.86. It suggests that, although none of the resilience capacities are very enabled, relatively the policy enables robustness the most, and transformability the least.

The results of the stakeholder check were integrated into the results of the analysis by adapting the ResAT wheel colors after the discussion with stakeholders. There were no adaptations of the wheel regarding robustness or transformability. In the case of adaptability, the middle-term focus was changed from level 3 to level 2. The change amounted to one point on a scale and was the result of the recognition of participants’ arguments regarding the difficulties to create not only long-term, but also middle-term plans by the actors.

3.5. Identification of Strengths and Weaknesses of Policies in Terms of Resilience

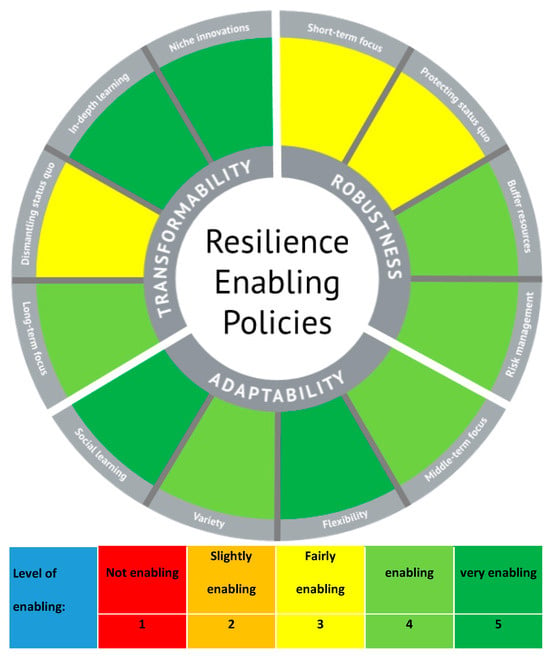

Policies support different capacities of resilience of farming systems to a different extent. Relatively, the most support is directed to robustness (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The Resilience Assessment Tool wheel for the Polish fruit and vegetable farming system from the view of stakeholders. Source: own study.

Short-term focus was assigned level 3 (see Figure 3—yellow color)—fairly enabling, because there is short-term support, but frequently it is not sufficient. There are also yearly allocations of the direct payments; however, they are not a very important part of the income of fruit and vegetable farms in Poland. They are also not always considered beneficial for the system, because short-term profits for small farmers discourage them from selling their lands to commercial farmers—“Direct payments are destroying our agriculture”.

Protecting status quo was assigned level 4 (see Figure 3—green color)—enabling, due to existing support for small farms, direct payments, and the favorable social insurance for farmers. There is also some coupled support still existing (which is a component of direct payments under the Common Agricultural Policy linked to the production of specific crops or livestock [82]), although on a very limited level.

Buffer resources were assigned level 4 (see Figure 3—green color)—enabling, due to the availability of funds for investments in physical assets, small farmer support, young farmer support, or direct payments. However, some respondents pointed out inequalities in relation to buffer resource support in different EU countries—“For example, farmers receive direct payments, but these should be distributed evenly. Why do farmers in the West get higher subsidies? We can’t compete under these conditions”.

Other risk management strategies were assigned level 3 (see Figure 3—yellow color)—fairly enabling, due to the fact, that despite the existence of risk management instruments, they do not always work properly, for example, insurances.

Adaptability was considered less supported than robustness. This is revealed by the following scoring by stakeholders.

Middle-term focus was assigned level 2 (see Figure 3—orange color)—slightly enabling, due to the time frame of the Pillar II instruments. However, respondents find it difficult to meet the requirements set by the funding agency—“Once, I inquired about it, there are many conditions to meet. One issue is that either production must be increased, or the acreage must be expanded within 5 years. With today’s land prices, this is difficult, and no one wants to sell their land”.

Flexibility was also assigned level 2 (see Figure 3—orange color)—slightly enabling, because of the focus on the means of achieving goals more than necessary and the lack of flexibility of procedures, with little regard to the situation of the system and the market.

Variety was assigned level 3 (see Figure 3—yellow color)—fairly enabling, due to the existence of different instruments within Pillar II for modernization of farms and supporting young farmers, as well as advisory services, but there are not many instruments dedicated to fruit and vegetable farming. There are some available, though—“There were likely resources available for fruit growers to receive substantial funding for preparing storage rooms and related activities. However, I can’t provide detailed information. This support is primarily aimed at groups and involves significant amounts of money”.

Social learning was assigned also level 3 (see Figure 3—yellow color)—fairly enabling, because there are advisory services provided, however they are not sufficient, according to some respondents. There is also support for groups of producers, which can be a platform for social learning—“Certainly, much progress has been made through these investment subsidies. This group is an example. I’m not sure it would have been created without these subsidies”.

Stakeholders considered transformability as the least supported. The marks for each element of its composition were evaluated as follows.

Long-term focus was assigned level 1 (see Figure 3—red color)—not enabling, due to lack of long-term strategies for the system—“We should aim for fewer farmers, but ensure they are permanently connected to the land. Their thinking should be long-term and multi-generational, considering the future of their grandchildren, not just the next six years”.

Dismantling status quo was assigned level 2 (see Figure 3—orange color)—slightly enabling, because of the direct payments, which are still keeping the status quo, although they are not as important for the fruit and vegetable farming system as for other farming systems. The coupled support is diminishing, although still existing on a limited level.

In-depth learning was assigned level 1 (see Figure 3—red color)—not enabling. the respondents could not indicate any policy instruments supporting in-depth learning.

Niche innovations were assigned level 2 (see Figure 3—orange color)—slightly enabling, due to the possibility of obtaining funds for innovations from the Regional Operation Programme; however, the process is characterized by extensive bureaucracy, and it is hard to gain funds for experimental projects. In the Rural Development Programme, the definition of innovation allows a broad range of activities to be treated as innovative, which allows spending of money on projects which are characterized by a low level of innovation—“For example, if the farmer didn’t have a tractor and then bought one, that is already an innovation. Similarly, introducing a new crop is an innovation. The entire Rural Development Programme is about fostering innovation, whatever that may entail [laughs]”.

3.6. The Future of the CAP—Results of the Workshop on Policy Recommendations

The results of the workshop covered policy recommendations generated by participants to obtain levels of support for robustness, adaptability, and transformability considered by stakeholders as the most desirable. Most of the recommendations were related, but not limited, to the Common Agricultural Policy. Results also included stakeholder views on different future scenarios and differences in the desired mix of support for different resilience capacities.

3.6.1. Round 1: Generic Policy Recommendations

The stakeholders discussed in the first place whether it should be a priority to enhance robustness, due to its short-term focus. The public sector, both at the European Union and national level (considering the participation from national funds), is considered necessary to ensure the continuity of actions, which increases the robustness of the system. Stakeholders agreed that at first it is needed to improve already existing policy instruments to enhance robustness, then to create new ones or new policies (better targeted). Mechanisms of direct market intervention are present, although are being withdrawn. European Union funds can heavily influence the stabilization of incomes, which are important buffer resources for strengthening robustness. A possible change would be to condition them more to provide public goods by farmers, through actions such as greening (but more precise in the evaluation of specific public goods’ values). Two main risks need to be addressed: risks related to weather and the price risk. However, there is very limited influence on both of them. Actors from all over the world influence the prices and the small, shaky markets; it is not possible to make predictions. However, the policy can influence insurance to affect the risk level. In the current system, it is not profitable for private companies, due to very high risk—the differences in prices at the fruit and vegetable markets are several times higher than on the grain market. Stakeholders pointed out the importance of retention in ensuring robustness, which should be addressed by the cohesion policy on rural areas, as well as by the Common Agricultural Policy and the national environmental policy.

Stakeholders pointed out that it is necessary to support value chains as well as horizontal and vertical integration, by increasing cooperation, like, for example, in Germany, where producers cooperate in processing the produced goods together. There are instruments to support the cooperation of farmers in Poland; however, there is little responsibility taken by farmers for actions and a fear of the need to give back the money in case of inadequate effects of actions. Also, the low level of social trust is a barrier. In this context, an advisory service is important, which is proven by good examples of countries like Denmark, where there is an extensive advisory system. It is important to improve not only technological advisory services, but also involve facilitators, who work with the region, not only with one farmer. Such facilitators can encourage the introduction of common projects. In addition, brokers of innovation are useful, encouraging different groups, such as farmers, advisors, scientists, etc., to realize common projects. Such projects are a chance to gain significant funds from the European Union budget. In the current system, one advisory agent is responsible for different tasks and there is not enough time for all those activities. Stakeholders see the need to divide those tasks between technological advisors, facilitators, and innovation brokers. However, some stakeholders were wondering if it makes sense to develop public advisory services, while in Polish fruit and vegetable farming system, private consulting is more often used and considered more effective. Stakeholders agreed that it is important to finance processing within producers’ groups, because financial incentives for cooperation are easier and faster to introduce than a change in mentality. It is important to note, however, that producers’ groups, which are formed around capital, are more likely to succeed if there is a higher level of trust between members, that in the groups, where the level of trust is lower. There was the suggestion that processing can be supported by food quality systems, which push farmers to create products which can make their mark.

Stakeholders concluded that it is important to focus on the long term, because both in Poland and in the European Union this is lacking. In some countries, like China (however with all positive and negative aspects of the strategy), the strategic scope is 50 years. One of the long-term goals suggested by stakeholders is vertical integration, for example, by facilitating co-ownership of processing facilities by producers. One of the ideas to do this is subsidization of enterprise shares instead of loans, which is costly. This way, in over a dozen years, it would be possible to increase the capital connection of different actors, which is viewed as beneficial for the Polish fruit and vegetable farming system. According to stakeholders, it is important to study trends of consumption (preferences and tastes) and adjust production profile to them. It is also important to improve the health value of products, which affects the choices of consumers. There is a need for more comprehensive look on policy, including the demand side, for example, by creating demand for fruits and vegetables by promoting healthy diets. Innovation in production should focus on health value and the novelty of products. However, some stakeholders suggested that there is too much focus on innovation and too little on cooperation and improvements in common project realization, which bonds the actors of the system much more than individual actions.

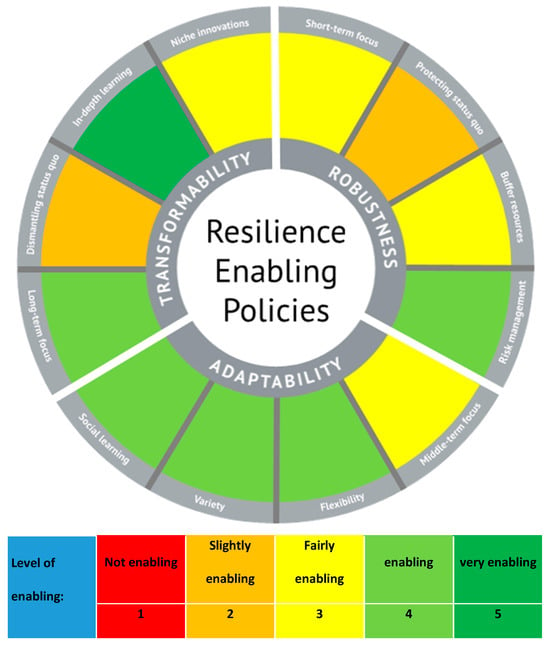

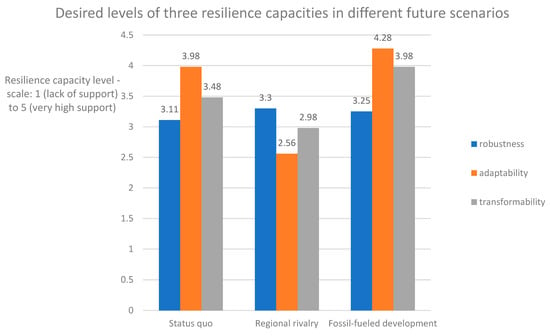

The discussion was ended with the following question: “if we apply the proposed policies and courses of action, what will be the level of desired robustness, adaptability, and transformability, and their 12 policy-enhancing characteristics?” The stakeholders were given printed versions of the ResAT wheel and they were asked to fill in the numbers on a scale of 1–5, where 1 (red) was the lowest value and 5 (dark green) was the highest. This approach allowed one to see the future mix of capacities desired by stakeholders under the status quo scenario, useful as a baseline for the comparison with future scenarios. According to stakeholders, in the future status quo scenario, priority should be given to supporting adaptation on a high level, followed by moderate support for transformability and robustness (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The Resilience Assessment Tool wheel for the Polish fruit and vegetable farming system in the future status quo scenario, based on stakeholder assessments on a scale of 1–5 during the CAP recommendations workshop. Source: own study.

The ResAT was also useful to find out how consistent proposed policies and courses of actions were with 12 resilience-enhancing policy characteristics. The results show that the generic policy recommendations suggested by participants were in line with the level of support of particular characteristics of resilience capacities assessed by participants as desired in the status quo scenario. In the case of robustness, enabling short-term focus was considered fairly important, mostly relevant to ensure continuity of actions. Stakeholders proposed changes to existing instruments and the adoption of new, more focused ones, so maintaining the status quo was considered only marginally significant. Buffer resources were considered fairly important, mostly significant for the stability of incomes. However, participants saw the need for conditioning it to provide goods by farmers, with precise evaluation of the value of the public goods produced. Enabling risk was considered the most important characteristic of robustness, as risks related to weather and price volatility need to be addressed. According to participants, it can be targeted indirectly, by reforming the insurance system. Another suggested means of dealing with risks related to unfavorable weather conditions was investments in retention, where not only the CAP but also cohesion policy and national environmental policy should play a crucial role.

Regarding adaptability, middle-term focus was considered fairly important. Flexibility was deemed crucial, as strict bureaucratic regulations and rigid project outcome requirements increase farmers’ fear of having to repay funds if they encounter difficulties in meeting the expected results. The importance of diverse and tailored solutions was also emphasized. Participants especially pointed out the need to introduce, except technological advisors, facilitators working in the region, to encourage farmers to start common projects and brokers of innovation to encourage different groups, such as farmers, advisors, scientists, etc., to realize common projects. This variety of advisory roles would be important in terms of social learning, another important characteristic of adaptability, especially in the context of value chains and vertical integration. Such activities have value in fostering collaboration, which is difficult to achieve in the Polish fruit and vegetable farming system due to a lack of social trust.

In the case of transformability, long-term focus was considered important for goals such as vertical integration of the system, as well as policies aimed at promoting healthy diet and consumption of local fruits and vegetables, in order to boost demand for those products. Dismantling the status quo was regarded only slightly important. In-depth learning was considered very important, because it is crucial to shift farmers’ mindsets in order to adapt to consumer demands and begin new forms of collaboration, such as agricultural producers co-owning processing facilities. Enhancement of niche innovations was considered fairly important, although participants stressed that facilitating innovations is not as important as support for cooperation. According to participants of the workshop, the most important is support for innovations increasing health value of the products and their novelty.

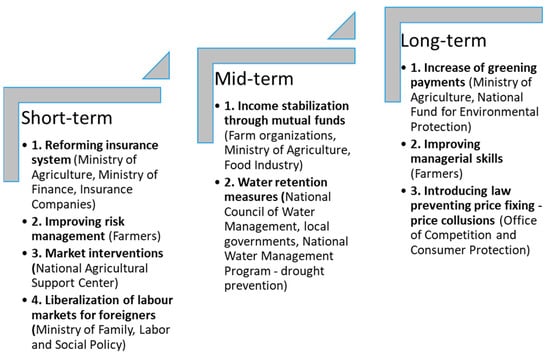

3.6.2. Round 2: CAP Recommendations

Stakeholders indicated several policy changes needed to enhance robustness (see Figure 5). Many of proposed actions were related to the short term, however some of suggestions were indicated in the medium term and even long term, as they were not possible to conduct within several months. In the short term, the most important action, according to participants, was improving risk management system at the national level, with a special emphasis on reforming the insurance system. Some stakeholders suggested liberalization of the national law on the labor market (especially international) to increase labor resources.

Figure 5.

Selected specific policies/actions for enabling robustness in order of their importance (top-down) and the main actors involved, according to stakeholders. Source: own study (based on discussions during the workshop).

Among suggestions to potentially be introduced in the medium term was income stabilization through mutual funds. To ensure water supply, the National Water Management Program needs to include actions allowing regional governments to provide water retention.

The main suggestion to be realized in the long term was increasing the share of greening payments in the CAP. Improving managerial skills of farmers was indicated as improving robustness, although it can also support other capacities of resilience. Some stakeholders suggested national market interventions as a way to increase robustness. Others suggested improving the law to prevent price fixing.

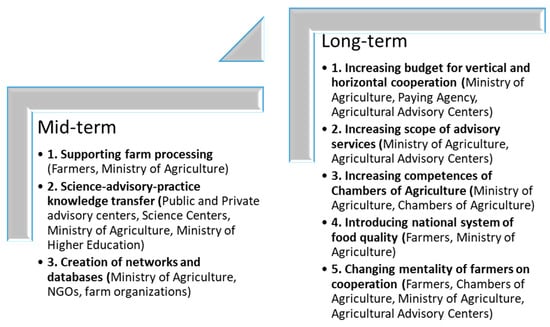

To enhance adaptability, participants suggested mid-term and long-term actions (see Figure 6). Among the mid-term solutions, support for processing by farmers was considered the most important. It was emphasized that the transfer of knowledge between science, advisory services, and farmers—both ways—should receive stronger support, for instance, through enhanced networking and the creation of centralized databases.

Figure 6.

Selected specific policies/actions for enabling adaptability in order of their importance (top-down) and the main actors involved, according to stakeholders. Source: own study (based on discussions during the workshop).

The most important long-term strategy, according to participants, was to increase the budget for programs enhancing vertical and horizontal integration. It was also suggested to change the scope of advisory services by including facilitators and brokers of innovations, and to increase salaries of public advisory agents. Another suggested action was changing the law on Chambers of Agriculture to increase their competences. A creation of a national system of food quality, which would enforce adaptability, was also suggested. In addition to policy changes, the need for changes in mentality in the context of cooperation was stressed.

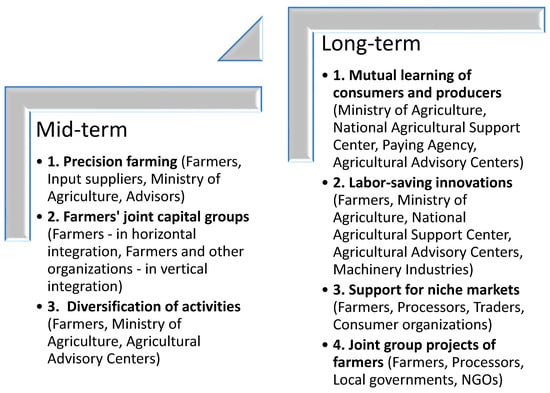

Participants had several ideas to enhance transformability in the medium term and long term (see Figure 7). The most important action in the mid-term was, according to participants, the creation of a national program to support precision farming. There was also an idea presented on launching a national program to integrate farmers through joint capital groups. Other one was increasing funds for support of the diversification of activities among producers and simplifying procedures to obtain them.

Figure 7.

Selected specific policies/actions for enabling transformability in order of their importance (top-down) and the main actors involved, according to stakeholders. Source: own study (based on discussions during the workshop).

The most important idea to be realized in the long term was mutual learning of consumers and producers, i.e., on the one side, producers would learn the consumers’ preferences, and on the other side, consumers would learn about healthy food via EU-wide education campaigns, which could increase demand for fruits and vegetables. Also, introducing national programs for innovations to improve quality and reduce labor consumption was suggested. The importance of support for niche markets was also stressed. Another suggestion was increasing funds for joint projects of groups of farmers. Another suggestion was related to searching and supporting niche markets.

Summing up, actions considered by participants as the most important for enabling robustness was the reform of the insurance system, improvements of risk management by farmers and stabilization of incomes by mutual funds (see Table 2). The most important actions for adaptability, according to participants, was an increase in funds for vertical and horizontal cooperation, supporting farm processing and increasing the scope of advisory services—including facilitators and brokers of innovation. Transformability requires mostly mutual learning of consumers and producers, labor-saving innovations, and introduction of precision farming.

Table 2.

Most important actions to enable robustness, adaptability, and transformability, based on workshop results.

3.6.3. Round 3: Recommendations Under Two Scenarios

In the third round of the workshop, stakeholders assessed the desired mix of policies under two different scenarios for future EU farming. The scenarios were based on the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) developed by O’Neil et al. [74]. Mathijs et al. [78] adjusted the available SSP narratives, which were developed for a whole global economy, to narratives significant for the EU farming systems. From the five scenarios (see Table 1), two were chosen for the workshop, which were the most different from each other in terms of policy—the most protectionist (SSP 3) and the most liberal scenario (SSP 5). After discussing each scenario, participants filled in the Resilience Assessment Tool wheel for the Polish fruit and vegetable farming system in this scenario based on the scale 1–5. At the end of the workshop, there was a feedback go-round about important take-aways and suggestions. The scenarios SSP 3 (Regional rivalry) and SSP 5 (Fossil-fueled development) were described to participants as stated in Table 3.

Table 3.

Description of SSP 3—Regional rivalry and SSP 5—Fossil-fueled development provided to participants of the workshop.

Scenario SSP 3—Regional rivalry (the most protectionist scenario)

According to stakeholders, in the scenario SSP 3, the desired level of robustness would be higher than in the current situation (see Figure 8). Less specialization would give more chance for robustness. In the scenario SSP 3, increasing mechanization and less labor-intensive activities would be needed to maintain a desired level of robustness, due to lack of labor force caused by migration limitation, as a result of protectionist policies. Such changes would need an increase in the desired level of buffer resources. More labor-intensive types of products might be imported from countries like China. Risk management would be slightly less important than in the status quo scenario, due to protectionist policies reducing risks related to price volatility. However, risks related to climate change and weather conditions still need to be addressed.

Figure 8.

The Resilience Assessment Tool wheel for the Polish fruit and vegetable farming system in the future regional rivalry scenario. Source: own study, based on the stakeholder assessment on a scale of 1–5 during the CAP recommendations workshop.

According to stakeholders, in the scenario SSP 3, it would be important to promote deconcentrating of capital and diversification of production, to meet the needs of local market. The public advisory would need to be more strongly supported, due to strong public intervention on the market, but the social learning and in-depth learning would be limited by low level of vertical cooperation. Flexibility would be less desired than in status quo scenario, due to relatively stable market conditions.

Transformability would not be much desired, especially in the area of niche innovations and in-depth learning, due to strong public market interventions and protectionism (see Figure 9). Furthermore, ecological innovations would receive little support, which is caused by a lack of ecological awareness.

Figure 9.

The Resilience Assessment Tool wheel for the Polish fruit and vegetable farming system in the future fossil-fueled development scenario. Source: own study, based on the stakeholder assessment on a scale of 1–5 during the CAP recommendations workshop.

Scenario SSP 5—Fossil-fueled development (the most neoliberal scenario)

In the scenario SSP 5, there would be greater desire for supporting adaptability and transformability (see Figure 9), because of the increased competition against producers from other countries, such as the USA. However, stakeholders do not consider this scenario very plausible, because it will be too risky for European agriculture, due to difficulties in competing with producers from other places in the world. Local producers would be strongly dependent on export.

Regarding robustness, stakeholders indicated that in the SSP 5 scenario, greening and renewable energy would decline in importance due to high costs and a stronger emphasis on technological development driven by fossil fuels. It would be important to assure business continuity; therefore, the importance of buffer resources might increase.

Considering adaptability, stakeholders assume that in the scenario SSP 5, quick adaptation processes will be very important due to more numerous threats. Therefore, flexibility would be very much desired. Vertical integration would not be developing, because large, international corporations would dominate the food industry, and the disproportion in the size would not allow producers to integrate with those companies. It would be necessary to support concentration of capital. Only horizontal integration would be developed to help farmers to obtain contracts with those big companies which are not interested in the small-scale supply of products. However, it would likely consider mostly big farms, not many small ones. Corporations seeking the cheapest products could impede it, though, increasing competition and hindering integration between producers. To avoid such negative effects, strengthening social learning would be very beneficial. Another way the internationalization of the food industry and free trade could affect adaptability of the system is that a public advisory would not be supported, and a private one would be dominating.

According to stakeholders, in the liberal scenario capital concentration would be encouraged in order to compete globally, and large corporations would be unwilling to share capital. Since competing with big, multinational companies in mainstream production would be difficult, smaller producers would need to develop in-depth learning, look for niches, and develop production within them.

3.6.4. Comparison of Different Future Scenarios