Abstract

Digital inclusive finance (DIF) is regarded as a key instrument in poverty alleviation efforts. However, existing research reveals significant gaps in understanding its poverty-reduction impact: the debate on its inclusivity remains unresolved, its mechanisms of action are unclear, and the psychological empowerment dimension has been largely overlooked. Using micro-level data from seven waves of the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) from 2010 to 2022, this study employs fixed-effect models, quantile regression models, and mechanism analysis to explore the differentiated impact of digital inclusive finance on rural multidimensional relative poverty and the mechanisms at play. The empirical findings reveal that DIF significantly mitigates multidimensional relative poverty, with more pronounced marginal effects among the poorest households, confirming its pro-poor characteristics. Heterogeneity analysis reveals that, at the regional level, DIF has greater impacts in western regions and remote rural areas farther from county centers; at the individual level, it is particularly effective for women, those with lower education, and individuals with limited digital literacy. Mechanism analysis shows that DIF operates through three channels: promoting employment, encouraging entrepreneurship, and enhancing financial accessibility. Moreover, extended analysis demonstrates that DIF also fosters the endogenous motivation of rural households to escape poverty, as reflected in heightened confidence about the future, increased belief in social mobility and returns of work, and reduced perceived barriers to employment. These findings provide new micro-level evidence to unpack the poverty-alleviation potential of DIF.

1. Introduction

Eradicating poverty remains a persistent and universal challenge [1,2,3]. Although substantial progress has been made globally in reducing poverty over recent decades, relative poverty remains widespread and continues to hinder inclusive and sustainable development [4,5]. In 2020, China achieved a historic victory in eliminating absolute poverty, prompting a strategic shift in national poverty governance toward addressing the more complex and concealed dimensions of relative poverty [6]. Unlike absolute poverty, relative poverty encompasses not only deficits in income and consumption but also broader deprivations in education, healthcare, employment, and subjective well-being [7,8,9]. Consequently, future poverty alleviation initiatives should aim to address the multidimensional and dynamic nature of poverty, a concept that has become a central consensus in international poverty research. Since 2012, China has consistently reduced poverty by over 10 million individuals annually and successfully eradicated both regional and absolute poverty by 2020.

As the global economy evolves, the scope of poverty alleviation has expanded from addressing the basic needs of “food, clothing, and shelter” to focusing on the developmental capacity of poor populations [10] Concurrently, the measurement of poverty has moved away from a single income-based indicator toward a more comprehensive multidimensional approach. Sen’s [11] capability poverty theory posits that poverty is not merely defined by low income but also by the lack of essential capabilities, such as the ability to avoid hunger, access education, and enjoy good health. Thus, multidimensional poverty research requires an integrated approach that goes beyond economic analysis to examine the absence of capabilities crucial to individual development. The concept of multidimensional poverty originated from welfare economics, with Sen’s capability approach emphasizing that poverty is not simply the lack of income but the absence of basic living capabilities, such as freedom from hunger, education, and health [11]. Fuchs [12] introduced relative poverty, emphasizing that poverty is defined in relation to the deprivation experienced by other social groups. Gurney and Tierney [13] argued that relative poverty refers to a state of deprivation when individuals lack access to food, infrastructure, services, and activities commonly available to others in society. Townsend [14] argued that poverty should be defined beyond absolute needs. Alkire and Foster [15] developed the A-F method, establishing thresholds for various dimensions and considering the degree of deprivation in each to determine multidimensional poverty, emphasizing that income alone cannot account for the full extent of poverty and advocating for a broader, more nuanced understanding of poverty.

Financial services have long been recognized as a key instrument in poverty alleviation [10]. At the micro level, they help poor households overcome liquidity constraints and facilitate investments in production, education, healthcare, and consumption [16,17,18,19,20]. At the macro level, financial development can stimulate regional industrial growth and expand employment and entrepreneurial opportunities, thereby fostering sustained poverty reduction [21,22,23]. However, conventional financial systems have often failed to serve rural populations effectively due to limited outreach, high costs, and poor accessibility [24].

In recent years, China has emerged as a global leader in digital payments. As of 2023, the national mobile payment penetration rate reached 86%, the highest worldwide. The volume of mobile payment transactions surged from 108.2 trillion yuan in 2015 to 555.3 trillion yuan in 2023, with an average annual growth rate of 64.14%. DIF—an innovative model combining digital technology with inclusive financial services—has played a pivotal role in addressing the financial exclusion faced by rural communities. Through tools such as mobile payments, online lending, and digital wealth management, digital finance has overcome the spatial and temporal constraints of traditional banking [25,26,27,28].

Extensive empirical evidence confirms that DIF can reduce financial service costs, enhance accessibility, and promote income growth and welfare improvement among rural populations [29,30,31]. For instance, Kenya’s M-Pesa significantly lowered poverty levels and strengthened women’s economic autonomy [32,33,34,35]. Bangladesh’s digital payment service bKash has been shown to raise rural incomes, enhance social inclusion, and reduce inequality [36,37,38]. In the business sector, the widespread use of digital financial tools has reduced financing difficulties for businesses, supported the growth of SMEs, and driven sustainable economic development [39,40,41]. Furthermore, digital inclusive finance (DIF) has played a crucial role in facilitating the digital transformation of enterprises, with technological innovation acting as a positive moderator and the financial background of executives having a negative moderating effect [42].

However, some studies point out that the poverty reduction effects of digital inclusive finance exhibit certain heterogeneity and limitations. The accessibility and effectiveness of digital financial services are often constrained by factors such as educational level, household income, and geographic location. These factors may exacerbate the disparities between disadvantaged and advantaged groups, leading to the emergence of issues such as the “digital divide”, “wealth inequality”, “social fragmentation”, and the “Matthew effect” [42,43,44,45,46,47]. Particularly in poor populations with lower educational levels and limited access to information, these negative effects are more pronounced [48,49]. While much of the literature focuses on objective poverty alleviation effects, there is a need to also consider endogenous development capabilities. Endogenous development capabilities refer to the intrinsic motivation, beliefs, and self-efficacy of individuals or households to mobilize their potential and resources when facing poverty and challenges. In the context of multidimensional poverty, endogenous development capabilities manifest as individuals’ confidence in the future and their expectations for social mobility and improved living standards [50].

A review of the existing literature reveals several notable gaps. First, most studies estimate average treatment effects, with insufficient attention paid to how different subgroups—particularly the ultra-poor—benefit from digital finance. Second, while much research has explored whether digital finance reduces poverty, few studies have unpacked how and why it does so. Third, the prevailing focus on static economic indicators such as income and consumption often neglects deeper psychological dimensions of poverty, including confidence, aspiration, and perceived mobility.

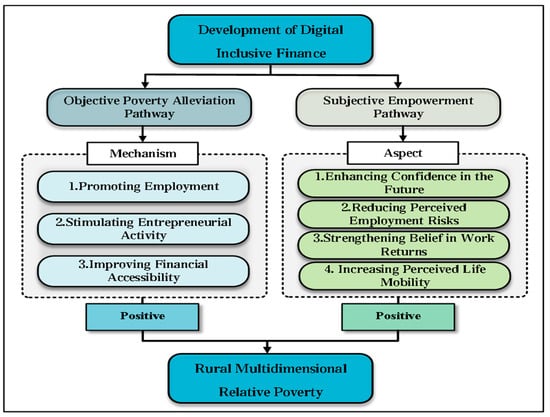

Against this backdrop, this study leverages CFPS micro-level panel data from 2010 to 2022 to conduct a comprehensive empirical examination of the impact of DIF on rural multidimensional relative poverty in China. The study offers several key contributions. First, by employing quantile regression and heterogeneous treatment effect estimation, we go beyond average effects to explore how digital finance impacts households at different poverty levels—thereby directly addressing whether digital inclusion truly benefits the poorest. Second, we integrate theoretical analysis with empirical testing to identify three mechanisms—employment promotion, entrepreneurial support, and financial access enhancement—through which digital finance alleviates poverty, thus shedding light on the “black box” of its functional logic. Third, this study integrates both objective and subjective dimensions of poverty alleviation into a unified framework. It not only validates the role of digital inclusive finance in alleviating objective poverty but also explores its effect on subjective poverty reduction by investigating its impact on farmers’ intrinsic motivation for development, thus offering a dual evaluation of both the “achievements” and the “potential” of digital inclusive finance.

The remainder of this study is structured as follows: Section 2 presents the theoretical framework underpinning the study. Section 3 describes the materials and methods used, detailing the data sources, variables, and analytical techniques. Section 4 provides the results and analysis. Section 5 offers an extended analysis. Finally, Section 6 discusses the conclusions drawn from the study, highlighting the key findings, limitations, and implications.

2. Theoretical Framework: How DIF Affects Rural Multidimensional Poverty

2.1. Employment Effect: Enhancing the Labor Market Participation of the Rural Poor

The multidimensional nature of poverty suggests that effective rural poverty reduction must involve improving individuals’ capacity for self-development. From a human capital perspective, rural households often face educational deficits and lack market-relevant skills, which limit their ability to participate meaningfully in the labor market [50,51,52,53]. DIF can ease liquidity constraints and increase household investment in education and health, which in turn strengthens human capital and enhances employability [54,55]. Furthermore, the expansion of digital financial services has contributed to the growth of non-agricultural sectors, such as rural service industries and small-scale manufacturing, generating new employment opportunities and enabling the rural poor to shift from low-productivity agricultural work to more productive forms of employment [56,57]. Digital financial tools also improve labor market information flow, reducing job search costs and increasing matching efficiency [58]. Overall, DIF not only creates employment opportunities for the poor but also improves the quality and efficiency of rural labor markets, which is laying a foundation for sustainable multidimensional poverty reduction.

2.2. Entrepreneurship Effect: Unlocking the Entrepreneurial Potential of Poor Households

Entrepreneurship plays a vital role in driving growth and reducing poverty, yet poor households often lack the capital and access to credit needed to launch and sustain business ventures [59,60]. Traditional finance, characterized by high transaction costs and strict collateral requirements, further limits access to entrepreneurial finance. DIF offers a promising solution. With its low marginal cost and data-driven credit systems, it reduces both the cost and barriers to financial service delivery (Jack & Suri, 2014; Du et al., 2023) [25,61]. Technologies such as mobile payments, big data analytics, and blockchain enable lenders to more accurately assess creditworthiness and mitigate information asymmetry and risk [62,63]. Moreover, digital ecosystems provide rural households with improved access to credit and market information, reducing the risks and costs associated with starting a business. This has helped spur entrepreneurship in underdeveloped areas and among low-income populations, transforming them from passive aid recipients to active participants in local economic development.

2.3. Mitigating Financial Exclusion: Expanding Access to Financial Services

Financial exclusion remains a major structural barrier to poverty reduction in rural areas. Poor households are often denied access to formal financial services due to low incomes, limited credit histories, and a lack of collateral [64,65]. On the supply side, sparse rural populations and the high costs of establishing physical bank branches have limited the reach of conventional finance [66]. On the demand side, low financial literacy and a weak perceived need for finance have led to the underuse and even avoidance of available services [67]. DIF—enabled by mobile connectivity and cost-efficient platforms—has fundamentally reshaped the accessibility of financial services. Remote onboarding, mobile transactions, and digital payments allow financial institutions to operate in remote areas without incurring high infrastructure costs [68]. Digital platforms also streamline procedures, reducing the time, effort, and information barriers for users and making services easier to access [69]. By lowering both the supply-side and demand-side frictions that drive financial exclusion, digital finance enables rural households to access credit for productive investment, health care, and education. These improvements can alleviate poverty across multiple dimensions. Based on this logic, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1.

DIF reduces multidimensional relative poverty in rural areas.

H2.

This effect is mediated through improved employment, enhanced entrepreneurship, and greater financial accessibility.

2.4. Motivational Effect: Fostering the Intrinsic Willingness to Escape Poverty

In addition to improving objective outcomes, DIF may also stimulate the internal motivation of poor individuals to lift themselves out of poverty. Traditional perspectives emphasize that poverty is not only material deprivation but also a deficit of opportunities, hope, and agency—factors that shape self-perception and aspirations [70]. Digital finance, unlike conventional financial services, leverages technologies such as the internet and big data to create a more inclusive and transparent economic environment. This helps enhance users’ perceived control and self-efficacy [50,71]. Specifically, digital inclusive finance reduces the financial constraints and transaction costs that poor groups face, enabling easier access to financial support for productive investments, education, and healthcare. This enhances their economic security and development expectations, fostering a more optimistic outlook on the potential for improving their future lives.

From a psychological perspective, the impact of digital inclusive finance is closely aligned with Self-Determination Theory (SDT), proposed by Deci and Ryan [72]. This theory posits that motivation stems from intrinsic needs, particularly self-efficacy, perceived control, and a sense of belonging. Within this framework, the widespread adoption of digital inclusive finance can strengthen individuals’ self-efficacy—belief in their ability to achieve goals—while also improving their sense of perceived control—belief in their ability to manage their life and future. The enhancement of these intrinsic motivations encourages impoverished individuals to take proactive steps to improve their living conditions, thus facilitating poverty reduction [50]. Meanwhile, the effects of digital inclusive finance can also be understood through the lens of Empowerment Theory, which emphasizes the autonomy and control of individuals or groups in social, economic, and political spheres [73]. By providing financial services, digital inclusive finance not only offers economic support to impoverished populations but, more importantly, empowers them with the ability to change their circumstances. By improving access to information and lowering the barriers to financial services, digital inclusive finance enables impoverished groups to seize more economic opportunities, thereby boosting their confidence and capabilities for future development.

Furthermore, wider access to markets and information also reduces uncertainty and improves perceptions of opportunity. As individuals become more confident in their ability to improve their lives and achieve upward mobility, their intrinsic motivation to work, invest, and innovate grows [72]. In this way, digital finance moves beyond simply providing external support and begins to foster self-driven empowerment and sustainable poverty reduction. Thus, we propose:

H3.

DIF can effectively stimulate the intrinsic motivation of poor households to escape poverty.

The overall theoretical framework is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Theoretical analysis framework.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Variable Specification

3.1.1. Dependent Variable: Multidimensional Relative Poverty Index

Following the multidimensional poverty identification approach proposed by Alkire and Foster [15], this study constructs a Multidimensional Relative Poverty Index (MRPI) based on five equally weighted dimensions: income, education, health, living conditions, and employment security. In line with prior research [74,75,76,77], each dimension is assigned an equal weight of 1/5, with sub-indicators within each dimension also weighted equally. The specific indicators and their assignments are outlined as follows (Table 1):

Table 1.

Indicator system for multidimensional relative poverty.

Income: A household is considered income-poor if its per capita net annual income falls below 40% of the rural median; assigned a value of 1, otherwise 0.

Education: Includes two indicators—the average years of schooling among household members aged 16 or above is less than 9 years (assigned 1, otherwise 0) and children aged 7–15 are not attending school (assigned 1, otherwise 0).

Health: Comprises three indicators—at least one adult in the household self-reports as “unhealthy” (assigned 1); at least one child (under 16) has three or more medical visits in a year (assigned 1); and household medical expenses exceed 50% of net income (assigned 1). Otherwise, all are assigned 0.

Living Conditions: Includes access to clean drinking water and cooking fuel: Drinking water is sourced from ponds, rainwater, rivers, springs, or cisterns (assigned 1). Cooking fuel consists of non-clean energy sources such as firewood or coal (assigned 1). Otherwise, 0.

Employment Security: If no working or previously employed adult in the household receives any formal employment-related social insurance (pension, health, unemployment, work injury, maternity), assigned 1; otherwise, 0.

3.1.2. Key Independent Variable

This study focuses on county-level digital inclusive finance development as the key independent variable (DIF). The Digital Inclusive Finance Index, developed by the Digital Inclusive Finance Research Center at Peking University, serves as the explanatory variable “https://idf.pku.edu.cn” (accessed on 25 January 2025). This index is the most widely utilized and authoritative tool for assessing the level of digital inclusive finance development across various regions in China. The dataset, published by the center, spans from 2010 to 2022 and includes data from over 2800 counties in 31 provinces, which is then matched with household sample data from these counties.

3.1.3. Mechanism Variables

To examine potential transmission mechanisms through which DIF alleviates poverty, three intermediary variables are defined:

Promoting Employment (Employment): Based on CFPS responses to whether an individual is currently engaged in paid work. Assigned 1 if employed, 0 otherwise.

Encouraging Entrepreneurship (Entrepre): Determined by whether any household member has operated a private business in the past 12 months, matched using household and individual data. Assigned 1 if present, 0 otherwise.

Enhancing Financial Accessibility (Finance): Measured by whether the household has any outstanding bank loans. Assigned 1 if yes, 0 otherwise.

3.1.4. Control Variables

In order to account for the impact of other factors on rural multidimensional relative poverty, this study introduces a set of control variables at both the household and regional levels. These control variables represent other critical factors that influence rural multidimensional relative poverty. At the household level, the variables include the education level (Educ), gender (Gen), age of the household head (Age), household assets (Asset), and family size of the household (Size). At the regional level, the control variables include the industrial structure of the county (Ind), the scale of foreign investment (Fdi), the per capita GDP (Gdp), and the degree of urbanization (Urban).

3.2. Model Specification

3.2.1. Baseline Regression Model

A fixed effects model is employed, as confirmed by the Hausman test, to estimate the impact of DIF on multidimensional relative poverty. The model is specified as follows:

where Povit denotes the multidimensional relative poverty index for household i in year t, DIFit is the county-level DIF index, Xit is a vector of control variables, μi and λt are household and year fixed effects, respectively, and εit is the error term.

3.2.2. Mediation Analysis Model

To identify the mechanisms by which DIF affects poverty, the following model is used to assess its impact on promoting employment, encouraging entrepreneurship, and enhancing financial accessibility:

where Mechanismit represents one of the three intermediary variables. The existing literature has extensively validated the income-enhancing effects of employment and entrepreneurship as well as the poverty-reducing benefits of inclusive financial access. Accordingly, the present analysis emphasizes the marginal effects of DIF on these mechanisms. A significant and robust association would confirm the presence of these specific pathways of impact.

3.3. Data Source and Processing

This study draws on seven waves (2010–2022) of the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS), which provides nationally representative longitudinal data from 29 provinces, covering household demographics, health, economic conditions, and social indicators. Data from the CFPS adult, child, household economic, and family relationship modules were merged using family identifiers. Urban households were excluded to focus on rural samples, yielding 35,798 valid household-year observations. Supplementary data on county-level economic characteristics were obtained from the China County Statistical Yearbook and the Peking University DIF Index Database. All data processing and regression analyses were conducted using Stata 16.0. Descriptive statistics for all variables are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of variables.

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Baseline Regression

To rigorously assess the impact of DIF on rural multidimensional poverty, this study adopts a stepwise regression approach, progressively introducing control variables to ensure the robustness of coefficient estimates (see Table 3). The estimation begins with household-level controls, including age, gender, education level, household assets, and family size. Subsequently, county-level macro controls are added: industrial structure, foreign direct investment (FDI), per capita GDP, and urbanization rate.

Table 3.

Baseline regression.

Columns (1) and (2) of Table 3 report results without individual and time-fixed effects, while columns (3) and (4) incorporate both. Across all model specifications, the coefficient on DIF remains significantly negative, indicating that the expansion of DIF significantly alleviates multidimensional poverty in rural areas. Specifically, in the models without fixed effects (columns 1–2), the coefficients for DIF are −0.0396 and −0.0569, both statistically significant at the 1% level. When individual and time-fixed effects are included (columns 3–4), the coefficients increase in magnitude to −0.0563 and −0.1008, again significant at the 1% level. These results suggest that the negative association between DIF and rural multidimensional poverty becomes stronger when accounting for unobserved heterogeneity, underscoring the robustness and strength of this relationship. Hence, Hypothesis 1 is proven.

Regarding control variables, higher education attainment, older age, greater household assets, and larger household size are all associated with significantly lower poverty scores, as indicated by the consistently negative and significant coefficients. In contrast, the gender of the household head has a significant positive coefficient, implying that male-headed households experience higher poverty levels than their female counterparts.

At the regional level, the coefficients for industrial structure and GDP per capita are significantly positive, possibly reflecting growing income inequality amid economic development. Conversely, FDI and urbanization have negative and significant coefficients, suggesting that greater capital inflows and urban integration help improve rural livelihoods by expanding employment opportunities and reducing poverty.

4.2. Endogeneity Test

To ensure the causal validity of the estimated relationship between DIF and rural multidimensional poverty, this study applies a two-stage least squares (2SLS) approach to address potential endogeneity. The diffusion of digital finance depends heavily on underlying information and communication infrastructure, which is historically linked to postal service coverage—an exogenous factor unrelated to current poverty levels. Additionally, digital finance originated in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, and the geographic proximity to this hub influences a region’s exposure to digital financial innovations, yet has no direct impact on poverty itself.

Following the established literature [78,79], two instrumental variables are constructed: (1) the interaction between the number of post offices per 100 residents in 1984 and the previous year’s internet penetration rate (historical_post offices), and (2) the spherical geographic distance from each county to Hangzhou, also interacting with lagged internet penetration (distance).

As shown in Table 4, both instruments are strongly and positively correlated with DIF in the first-stage regressions, with coefficients of 0.7958 and 0.7539, respectively, each significant at the 1% level. These results confirm the instruments’ relevance and exclude weak identification concerns. In the second-stage regressions, DIF remains significantly negative, with coefficients of −0.1186 and −0.0583. This confirms the robustness of the causal effect of DIF in reducing rural multidimensional poverty.

Table 4.

Endogeneity test.

4.3. Robustness Test

To further test the reliability of the baseline findings, three robust checks are conducted. First, all observations from Zhejiang Province—where digital finance originated—are removed to address potential bias due to regional overrepresentation. Second, the dependent variable is redefined using a binary indicator based on the national poverty line of 4000 RMB (2020), coded as 1 if the household income falls below this threshold and 0 otherwise. Third, continuous variables are winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles to minimize the influence of outliers.

Across all three robustness tests (Table 5), the estimated coefficients for DIF remain significantly negative, reinforcing the validity and consistency of the main conclusions.

Table 5.

Robustness test.

4.4. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.4.1. Heterogeneity by Poverty Quantile

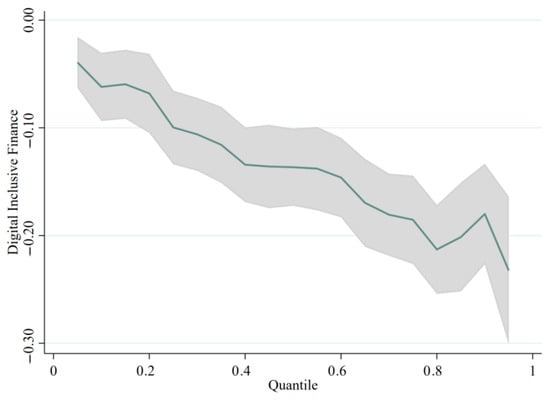

Recognizing that the impact of DIF may vary across the poverty distribution, this study employs a quantile regression framework to explore distributional heterogeneity. The analysis divides the rural population into ten deciles according to their multidimensional poverty levels with household- and region-level controls included.

Figure 2 illustrates the variation in treatment effects across poverty levels. As poverty deepens (i.e., higher quantiles), the absolute value of the DIF coefficient increases, suggesting that DIF delivers stronger poverty reduction benefits to the most disadvantaged households. This trend highlights a marginal benefit issue in economics, where the marginal benefit of digital inclusive finance is greatest for the poorest groups. This finding underscores the “poverty-reducing” nature of digital inclusive finance, showing that its effect is most notable for the most impoverished populations. Practically, this heterogeneity suggests that digital inclusive finance not only reduces the overall level of rural multidimensional poverty but is especially effective for the most disadvantaged, helping to reduce inequality within impoverished communities.

Figure 2.

Heterogeneity by poverty quantile.

4.4.2. Regional Heterogeneity

China’s vast geography and regional diversity give rise to marked differences in economic development, governance capacity, and cultural norms. These disparities may significantly shape how DIF impacts rural multidimensional poverty across the country. To explore such regional heterogeneity, this study considers both macro-geographic divisions and spatial proximity to administrative centers.

First, the sample was segmented into eastern, central, and western regions. The regression results in Table 6 reveal that DIF has a statistically significant negative association with rural multidimensional poverty in all three regions, with coefficients of −0.1202 (east), −0.1097 (central), and −0.1492 (west), all at the 1% significance level. Among them, the west shows the strongest effect. This is likely due to its relatively weaker economic base and lower penetration of traditional financial services, making the marginal gains from DIF more pronounced. In contrast, the eastern region, while more affluent overall, continues to grapple with relative poverty, and DIF plays an important role in equalizing financial access and expanding opportunity.

Table 6.

Regional heterogeneity.

Second, rural households were classified by their distance from county centers. Using survey responses on travel time, we distinguished between “proximate” and “remote” villages. The analysis reveals that DIF exerts a substantially greater poverty-reducing impact in remote areas (coefficient = −0.1719) than in those closer to county seats (coefficient = −0.0921), both results significant at the 1% level. This suggests that DIF is especially effective in underserved regions where traditional financial services are limited. The stronger effects observed in remote areas reflect the compensatory role of digital finance in extending the reach of poverty alleviation tools, reinforcing its promise as a mechanism for promoting regional equity.

4.4.3. Individual-Level Heterogeneity

Beyond regional differences, this study explores how the impact of Digital Inclusive Finance (DIF) on multidimensional poverty varies across individuals with different characteristics. Rural households differ significantly in terms of gender, education, and digital literacy, which may lead to differentiated responses to financial interventions. To examine these variations, we conduct subgroup regressions based on three dimensions:

Gender: Samples are divided into male and female groups to assess gender-based differences in the effectiveness of DIF.

Education: Individuals are classified as low education or high education based on whether their years of schooling fall below or exceed the sample average (9.1754 years).

Digital literacy: Digital proficiency is measured by the frequency of using the internet for learning (on a 1–7 scale). Scores of 1–4 indicate low digital literacy, and 5–7 indicate high digital literacy.

The results are presented in Table 7. The analysis shows that DIF has a stronger poverty reduction effect among women, suggesting that digital finance may compensate for their historical exclusion from formal financial systems. The flexibility and accessibility of digital tools may help women access new economic opportunities, leading to greater marginal benefits. Similarly, individuals with lower levels of education benefit more from DIF. This indicates that those with limited formal schooling rely more heavily on digital financial services, underscoring the compensatory nature of DIF in reaching underserved populations. Surprisingly, those with lower digital literacy also show greater gains. This may be due to a “basic access effect”—even limited digital skills can unlock meaningful improvements in financial access and household welfare, particularly when platforms are designed to be user-friendly.

Table 7.

Individual heterogeneity.

These findings highlight a broader point. While DIF appears especially effective for women, less-educated individuals, and those with low digital proficiency, this does not imply that it is ineffective for men, highly educated individuals, or digitally skilled users. Rather, the stronger marginal effects observed among disadvantaged groups likely reflect their lower baseline access to financial resources and services. In contrast, better-off groups—who face fewer constraints—naturally exhibit smaller marginal improvements. This phenomenon reflects a “poverty gradient paradox”: those with the least access stand to gain the most. Importantly, this does not diminish the significance of DIF for more advantaged groups but rather affirms its value in equity-oriented resource allocation. The greatest contribution of digital inclusive finance may not lie in raising average outcomes but in precisely reaching and meaningfully improving the lives of those most often excluded from traditional financial systems.

4.5. Mechanism Analysis

To uncover the pathways through which DIF alleviates multidimensional poverty, this study tests three theoretical channels: enhancing employment, promoting entrepreneurship, and improving access to financial services. Table 8 presents the corresponding regression results.

Table 8.

Results of the impact mechanism analysis.

First, DIF significantly increases the likelihood of employment among rural households (coefficient = 0.1048, p < 0.01), suggesting that digital tools may enhance labor market participation by improving access to job-related information and reducing search costs. Second, DIF positively influences household entrepreneurship (coefficient = 0.0874, p < 0.01), indicating that expanded access to financial tools encourages business formation and self-employment among the rural poor. Third, the strongest effect is observed in financial accessibility (coefficient = 0.1753, p < 0.01), reflecting DIF’s success in easing credit constraints and reducing financial exclusion. By lowering both the supply- and demand-side barriers to finance, digital platforms enable poor households to invest in productive activities, manage risks, and smooth consumption, thereby substantially mitigating their multidimensional deprivation. Consequently, Hypothesis 2 is validated.

5. Extended Analysis: Stimulating Subjective Motivation for Poverty Alleviation

While previous sections focused on the objective impact of DIF on multidimensional rural poverty, effective poverty reduction strategies must also attend to the internal motivation of impoverished groups. Beyond improving material conditions, sustainable poverty alleviation requires cultivating individuals’ belief in their own capacity to improve their lives.

To assess this dimension, the study introduces four subjective indicators reflecting an individual’s psychological drive to escape poverty: (1) confidence in the future, (2) perceived severity of employment challenges, (3) perceived return to effort, and (4) perceived opportunity for life improvement. These variables are derived from the CFPS questionnaire. Specifically, respondents rated their confidence in the future on a scale of 1–5 (higher values indicate stronger optimism); concern about employment issues on a scale of 0–10 (higher values indicate more severe perceived problems); belief that hard work is rewarded on a scale of 1–5; and perception of opportunities for improving living standards, also on a 1–5 scale.

To assess the influence of digital inclusive finance on farmers’ subjective motivation for poverty alleviation, and given that these subjective variables are ordinal discrete variables, an ordered Probit model is employed. The following ordered Probit regression model is constructed:

where Yit denotes each subjective motivation variable, DIFit measures the level of digital financial development in the respondent’s county, and the remaining terms follow the benchmark model specifications.

As shown in Table 9, DIF has a statistically significant positive impact on future confidence (coefficient = 0.2726), perceived returns to effort (0.3345), and life improvement expectations (0.4828), while significantly reducing the perceived severity of employment challenges (−0.9707). Therefore, Hypothesis 3 is substantiated.

Table 9.

Results of stimulating subjective motivation for poverty alleviation.

In summary, these findings suggest that DIF has not only improved the economic conditions of poor farmers but also, and more importantly, significantly triggered their subjective motivation for poverty reduction. From the perspective of Self-Determination Theory and Empowerment Theory, digital inclusive finance has effectively fostered the activation of their intrinsic motivations. This internal drive is manifested in the enhancement of psychological empowerment and self-efficacy. In this study, farmers’ increased confidence in the future, reduced concerns about employment, stronger belief in work-related rewards, and greater hope for improving their living standards all reflect a positive change in their mindset. This shift has not only motivated farmers to take concrete actions to improve their lives but has also established a psychological foundation for sustainable poverty alleviation efforts.

6. Discussion

This study provides comprehensive empirical evidence on the differentiated impacts of DIF on multidimensional relative poverty in rural China, drawing on micro-level data from seven waves of the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) between 2010 and 2022. Our findings reinforce and extend existing literature, confirming the pro-poor characteristics of digital financial services while uncovering nuanced heterogeneity and mechanisms that previous studies often overlooked.

First, our results align with previous evidence suggesting that DIF substantially reduces poverty by enhancing financial accessibility, fostering employment, and stimulating entrepreneurial activities [25,30,57]. However, our study goes beyond affirming these outcomes, revealing that the poverty-reduction effects are disproportionately stronger among the poorest rural households, thereby directly addressing ongoing debates regarding the “digital divide” and the potential for digital finance to inadvertently widen socioeconomic gaps [45,46]. This finding enriches the literature by clearly demonstrating DIF’s ability to effectively target and benefit the most vulnerable segments of the population.

Moreover, regional heterogeneity analyses contribute novel insights to the discourse on geographic disparities in financial inclusion. Consistent with prior observations that digital financial solutions are particularly impactful in underdeveloped regions [32,33], our findings illustrate a pronounced effectiveness of DIF in China’s western rural regions and more remote villages. This highlights DIF’s essential role as a compensatory mechanism addressing regional imbalances caused by traditional financial infrastructures’ shortcomings.

Crucially, a key contribution of this study is its expansion of the theoretical framework in poverty reduction research by introducing the long-neglected dimension of “subjective motivation for poverty alleviation”. The empirical results show that digital inclusive finance significantly improves farmers’ psychological capital by enhancing their optimism about the future, reducing their perception of employment barriers, and strengthening their belief in economic mobility. Given the current shift in poverty alleviation efforts towards addressing relative poverty, these subjective factors are increasingly crucial, as the focus has moved from absolute to relative poverty. Subjective agency, in this context, is the most effective means of addressing relative poverty. This finding offers direct empirical support for the theory of “psychological empowerment driving sustainable poverty reduction” [50,71], emphasizing the critical role of intrinsic motivation and psychological factors in poverty management.

Nevertheless, several limitations of this study warrant careful consideration. Firstly, our research employs data specific to China, where rapid digital finance development, robust infrastructure, and strong governmental support provide a unique enabling environment. Thus, the generalizability of findings to contexts with less developed digital infrastructures or weaker institutional support may be limited. Secondly, despite robust methodological approaches addressing endogeneity, the possibility of residual confounding due to unobserved variables remains. Future research could enhance validity by incorporating experimental or quasi-experimental methods and comparative cross-national analyses to validate these findings.

In conclusion, our study establishes that DIF significantly mitigates multidimensional rural poverty and is particularly beneficial for the poorest households through mechanisms of employment enhancement, entrepreneurial stimulation, and improved financial accessibility. More importantly, DIF also profoundly influences subjective factors by bolstering rural households’ self-confidence and reducing psychological barriers to self-improvement, fostering sustainable and intrinsic poverty alleviation.

In light of the findings, the following policy suggestions are offered: First, focus on closing the digital divide by prioritizing technologies and infrastructure tailored to rural areas, with directed investments in digital infrastructure for remote and disadvantaged regions to ensure physical access to inclusive financial services. Second, enhance financial capacity by creating specialized financial literacy programs to assist farmers in maximizing the benefits of digital financial services. Third, integrate psychological support mechanisms by incorporating psychological capital development into poverty alleviation strategies to fully unlock the transformative potential of digital finance. Furthermore, financial institutions should make full use of digital technologies to create and promote inclusive financial products and services that cater to economically disadvantaged and financially vulnerable populations, ensuring these products are inclusive, convenient, and cost-effective. Additionally, as digital finance expands in rural areas, there is a growing need to improve legal safeguards. Policymakers should strengthen judicial oversight by integrating legal education within digital finance platforms, promoting online arbitration and mediation as accessible alternatives for resolving financial disputes efficiently; enhance civil litigation frameworks to ensure timely and affordable access to legal recourse, especially for rural residents; and train judicial officials in digital finance laws to handle related disputes effectively.

7. Conclusions

This study, based on data from the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) from 2010 to 2022, with a sample of 35,798, delves into the differentiated effects and underlying mechanisms of digital inclusive finance in alleviating rural multidimensional relative poverty. The results demonstrate that digital inclusive finance significantly reduces multidimensional poverty in rural areas, with the poverty alleviation effect being especially significant for deeper poverty groups, showcasing its “pro-poor” characteristics. Further analysis of heterogeneity reveals that digital inclusive finance has a more substantial poverty reduction effect in the western regions and rural areas that are farther from county seats, confirming its efficacy in economically lagging regions. At the individual level, DIF yields greater benefits for women, the less educated, and those with lower digital literacy, suggesting that digital inclusive finance is most effective among disadvantaged groups, underscoring its role as a targeted poverty alleviation tool. In addition, the study systematically analyzes how digital inclusive finance alleviates poverty by promoting employment, fostering entrepreneurship, and improving the accessibility of financial services.

Notably, digital inclusive finance not only alleviates poverty at the economic level but also plays an important role in stimulating the subjective motivation for poverty alleviation. By enhancing farmers’ confidence in the future, improving their perception of employment issues, and increasing their recognition of work rewards and life improvement opportunities, digital inclusive finance significantly boosts their intrinsic motivation, offering psychological support and driving force for long-term poverty reduction. Overall, this study provides new insights into the multidimensional effects of digital inclusive finance on poverty governance and offers empirical support for policymakers working to promote digital finance policies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.W., Q.L., M.W. and D.W.; methodology, Q.L., M.W. and D.W.; software, Q.L. and D.W.; validation, Q.L. and D.W.; data curation, Q.L., M.W. and D.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.W., M.W., Q.L. and D.W.; writing—review and editing, Q.L., M.W. and D.W.; visualization, Q.W., M.W. and D.W.; supervision, Q.W., M.W. and D.W.; project administration, Q.W.; funding acquisition, Q.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was sponsored in part by The National Social Science Fund of China “Research on mechanism of Government purchasing Welfare Service for Rural Left-behind Children from the perspective of collaborative governance” (21BGL232).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lee, B.X.; Kjaerulf, F.; Turner, S.; Cohen, L.; Donnelly, P.D.; Muggah, R.; Davis, R.; Realini, A.; Kieselbach, B.; MacGregor, L.S.; et al. Transforming our world: Implementing the 2030 agenda through sustainable development goal indicators. J. Public Health Policy 2016, 37, 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakner, C.; Mahler, D.G.; Negre, M.; Prydz, E.B. How much does reducing inequality matter for global poverty? J. Econ. Inequal. 2022, 20, 559–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Li, S. Eliminating poverty through development: The dynamic evolution of multidimensional poverty in rural China. Econ. Political Stud. 2022, 10, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, D.; Prydz, E.B. Societal poverty: A relative and relevant measure. World Bank Econ. Rev. 2021, 35, 180–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decerf, B.; Ferrando, M. Unambiguous trends combining absolute and relative income poverty: New results and global application. World Bank Econ. Rev. 2022, 36, 605–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, G.; Hu, X.; Liu, W. China’s poverty reduction miracle and relative poverty: Focusing on the roles of growth and inequality. China Econ. Rev. 2021, 68, 101643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betti, G.; Verma, V. Fuzzy measures of the incidence of relative poverty and deprivation: A multi-dimensional perspective. Stat. Methods Appl. 2008, 17, 225–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Wei, X. How can digital financial inclusion reduces relative poverty? An empirical analysis based on China household finance survey. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 58, 104570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, W.; Cheng, X.; Fan, Z.; Yin, W. Multidimensional relative poverty in China: Identification and decomposition. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkire, S.; Foster, J.; Seth, S.; Santos, M.E.; Roche, J.M.; Ballon, P. Multidimensional Poverty Measurement and Analysis; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Conceptualizing and measuring poverty. Poverty Inequal. 2006, 30, 46. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, V. Redefining poverty and redistributing income. Public Interest 1967, 8, 88. [Google Scholar]

- Gurney, J.N.; Tierney, K.J. Relative deprivation and social movements: A critical look at twenty years of theory and research. Sociol. Q. 1982, 23, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, P. The meaning of poverty. Br. J. Sociol. 1962, 13, 210–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkire, S.; Foster, J. Counting and multidimensional poverty measurement. J. Public Econ. 2011, 95, 476–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T.; Demirgüç-Kunt, A.; Levine, R. Finance, inequality and the poor. J. Econ. Growth 2007, 12, 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.S.; Chalk, R.; Ladd, H.F. (Eds.) Equity and Adequacy in Education Finance: Issues and Perspectives; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, T.; Levine, R.; Loayza, N. Finance and the Sources of Growth. J. Financ. Econ. 2000, 58, 261–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, T.; Holtz-Eakin, D. Financial capital, human capital, and the transition to self-employment: Evidence from intergenerational links. J. Labor Econ. 2000, 18, 282–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A.; Klapper, L.F. Financial inclusion in Africa: An overview. World Bank Policy Res. Work. Pap. 2012, 6088. [Google Scholar]

- Honohan, P. Financial development, growth and poverty: How close are the links? In Financial Development and Economic Growth: Explaining the Links; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2004; pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Chodorow-Reich, G. The employment effects of credit market disruptions: Firm-level evidence from the 2008–2009 financial crisis. Q. J. Econ. 2014, 129, 1–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Wang, K.; Xu, H.; Li, M. Has digital financial inclusion narrowed the urban-rural income gap: The role of entrepreneurship in China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, R.; Pande, R. Do rural banks matter? Evidence from the Indian social banking experiment. Am. Econ. Rev. 2005, 95, 780–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, W.; Suri, T. Risk sharing and transactions costs: Evidence from Kenya’s mobile money revolution. Am. Econ. Rev. 2014, 104, 183–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, B. Digital inclusive finance and urban innovation: Evidence from China. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2022, 26, 1010–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, F.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, M. Digital financial inclusion, traditional finance system and household entrepreneurship. Pac. Basin Financ. J. 2023, 80, 102076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, Y.; Yang, L.; Wang, Z. Does the development of digital inclusive finance promote the construction of digital villages?—An empirical study based on the Chinese experience. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asongu, S. The impact of mobile phone penetration on African inequality. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2015, 42, 706–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelikume, I. Digital financial inclusion, informal economy and poverty reduction in Africa. J. Enterprising Communities People Places Glob. Econ. 2021, 15, 626–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugwuanyi, U.; Ugwuoke, R.; Onyeanu, E.; Festus Eze, E.; Isahaku Prince, A.; Anago, J.; Ibe, G.I. Financial inclusion-economic growth nexus: Traditional finance versus digital finance in Sub-Saharan Africa. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2022, 10, 2133356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morawczynski, O. Exploring the usage and impact of “transformational” mobile financial services: The case of M-PESA in Kenya. J. East. Afr. Stud. 2009, 3, 509–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndiaye, O.K. Is the success of M-Pesa empowering Kenyan rural women? Fem. Afr. 2013, 18, 156–161. [Google Scholar]

- Mbiti, I.; Weil, D.N. Mobile banking: The impact of M-Pesa in Kenya. In African Successes, Volume III: Modernization and Development; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2015; pp. 247–293. [Google Scholar]

- Ndung’u, N. The M-Pesa technological revolution for financial services in Kenya: A platform for financial inclusion. In Handbook of Blockchain, Digital Finance, and Inclusion; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; Volume 1, pp. 37–56. [Google Scholar]

- Uddin, M.S.; Akhi, A.Y. E-wallet system for Bangladesh an electronic payment system. Int. J. Model. Optim. 2014, 4, 216–219. [Google Scholar]

- Mujeri, M.K.; Azam, S. Role of Digital Financial Services in Promoting Inclusive Growth in Bangladesh: Challenges and Opportunities. Inst. Incl. Financ. Dev. Work. Pap. 2018, 55, 5–25. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.J.; Mia, M.R. The evolution of payment systems in Bangladesh: Transition from traditional banking to blockchain based transactions. Malays. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2024, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyman, O. Accelerating Financial Inclusion in South-East Asia with Digital Finance; Asian Development Bank: Manila, Philippines, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Banna, H.; Alam, M.R. Is Digital Financial Inclusion Good for Bank Stability and Sustainable Economic Development? Evidence from Emerging Asia; ADBI Working Paper Series. 2021. Available online: https://www.adb.org/publications/digital-financial-inclusion-good-bank-stability-sustainable-economic-development-asia (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Morgan, P.J. Fintech and financial inclusion in Southeast Asia and India. Asian Econ. Policy Rev. 2022, 17, 183–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Feng, Y.; Lin, J. Digital inclusive finance and digital transformation of enterprises. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 57, 104270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arestis, P.; Caner, A. Financial liberalization and the geography of poverty. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2009, 2, 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank Group. World Development Report 2016: Digital Dividends; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ragnedda, M. The Third Digital Divide: A Weberian Approach to Digital Inequalities; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Ke, J. Three-level digital divide: Income growth and income distribution effects of the rural digital economy. Agric. Technol. Econ. 2021, 8, 119–132. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, X.; Chen, Q.; Man, D.; Shi, C.; Wang, N. The impact of digitalization on the rich and the poor: Digital divide or digital inclusion? Technol. Soc. 2024, 78, 102634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsetsi, E.; Rains, S.A. Smartphone Internet access and use: Extending the digital divide and usage gap. Mob. Media Commun. 2017, 5, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, B.H. Hidden constraints to digital financial inclusion: The oral-literate divide. Dev. Pract. 2019, 29, 1014–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; Wessels, S. Self-Efficacy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, G.S. Human Capita; National Bureau of Economic Research: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, P.; Yu, Z. Rural poverty and mobility in China: A national-level survey. J. Transp. Geogr. 2021, 93, 103083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouko, K.O.; Ogola, J.R.; Ngonga, C.A.; Wairimu, J.R. Youth involvement in agripreneurship as Nexus for poverty reduction and rural employment in Kenya. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2022, 8, 2078527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asongu, S.A.; Nnanna, J.; Acha-Anyi, P.N. Finance, inequality and inclusive education in Sub-Saharan Africa. Econ. Anal. Policy 2020, 67, 162–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhuge, R.; Han, J.; Zhao, P.; Gong, M. Research on the impact of digital inclusive finance on rural human capital accumulation: A case study of China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 936648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elouardighi, I.; Oubejja, K. Can digital financial inclusion promote women’s labor force participation? Microlevel evidence from Africa. Int. J. Financ. Stud. 2023, 11, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qi, Y.; Li, Y. How does digital inclusive finance influence non-agricultural employment among the rural labor force?—Evidence from micro-data in China. Heliyon 2024, 13, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, K. Mobile money for financial inclusion. Inf. Commun. Dev. 2012, 61, 61–73. [Google Scholar]

- Stiglitz, J.E.; Weiss, A. Credit rationing in markets with imperfect information. Am. Econ. Rev. 1981, 71, 393–410. [Google Scholar]

- Conning, J.; Udry, C. Rural financial markets in developing countries. Handb. Agric. Econ. 2007, 3, 2857–2908. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, J. How does digital inclusive finance affect economic resilience: Evidence from 285 cities in China. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2023, 88, 102709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaquias, F.F.O.; Hwang, Y. Trust in mobile banking under conditions of information asymmetry: Empirical evidence from Brazil. Inf. Dev. 2016, 32, 1600–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xiao, W.; Bai, C. Can renewable energy technology innovation alleviate energy poverty? Perspective from the marketization level. Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, P. Improving Access to Finance for India’s Rural Poor; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Makoni, P.L. From financial exclusion to financial inclusion through microfinance: The case of rural Zimbabwe. J. Corp. Ownersh. Control. 2014, 11, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T.; Demirgüç-Kunt, A.; Honohan, P. Access to financial services: Measurement, impact, and policies. World Bank Res. Obs. 2009, 119–145. Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/547661468161359586 (accessed on 25 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Falola, A.; Olowogbon, T.S.; Mukaila, R.; Ayodele, O.S.; Ibrahim, F. Financial literacy of rural farming households in Kwara State, Nigeria: A guide for financial inclusion. J. Rural. Community Dev. 2023, 18, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Honohan, P. Cross-country variation in household access to financial services. J. Bank. Financ. 2008, 32, 2493–2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazarbasioglu, C.; Mora, A.G.; Uttamchandani, M.; Natarajan, H.; Feyen, E.; Saal, M. Digital financial services. World Bank 2020, 54. Available online: https://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/230281588169110691/digital-financial-services.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Walker, R. Bantebya-Kyomuhendo G. The Shame of Poverty; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mossberger, K.; Tolbert, C.J.; McNeal, R.S. Digital Citizenship: The Internet, Society, and Participation; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Edward, L.D.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Julian, R. Terms of empowerment/exemplars of prevention: Toward a theory for community psychology. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1987, 15, 121–148. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y. Multidimensional relative poverty of rural women: Measurement, dynamics, and influencing factors in China. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1024760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Zhao, P.; Zhao, Y.; Saddique, R. The multidimensional relative poverty of rural older adults in China and the effect of the health poverty alleviation policy. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 793673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Hu, X. The common prosperity effect of rural households’ financial participation: A perspective based on multidimensional relative poverty. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1457921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Hammond, A. Serving the world’s poor, profitably. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2002, 80, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bai, T.; Qi, Y.; Li, Z.; Xu, D. Digital economy, industrial transformation and upgrading, and spatial transfer of carbon emissions: The paths for low-carbon transformation of Chinese cities. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 344, 118528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Ye, W.; Han, F. Does the digital economy promote industrial collaboration and agglomeration? Evidence from 286 cities in China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).