Farmers’ Experiences of Transitioning Towards Agroecology: Narratives of Change in Western Europe

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Policy Context

3. Materials and Methods

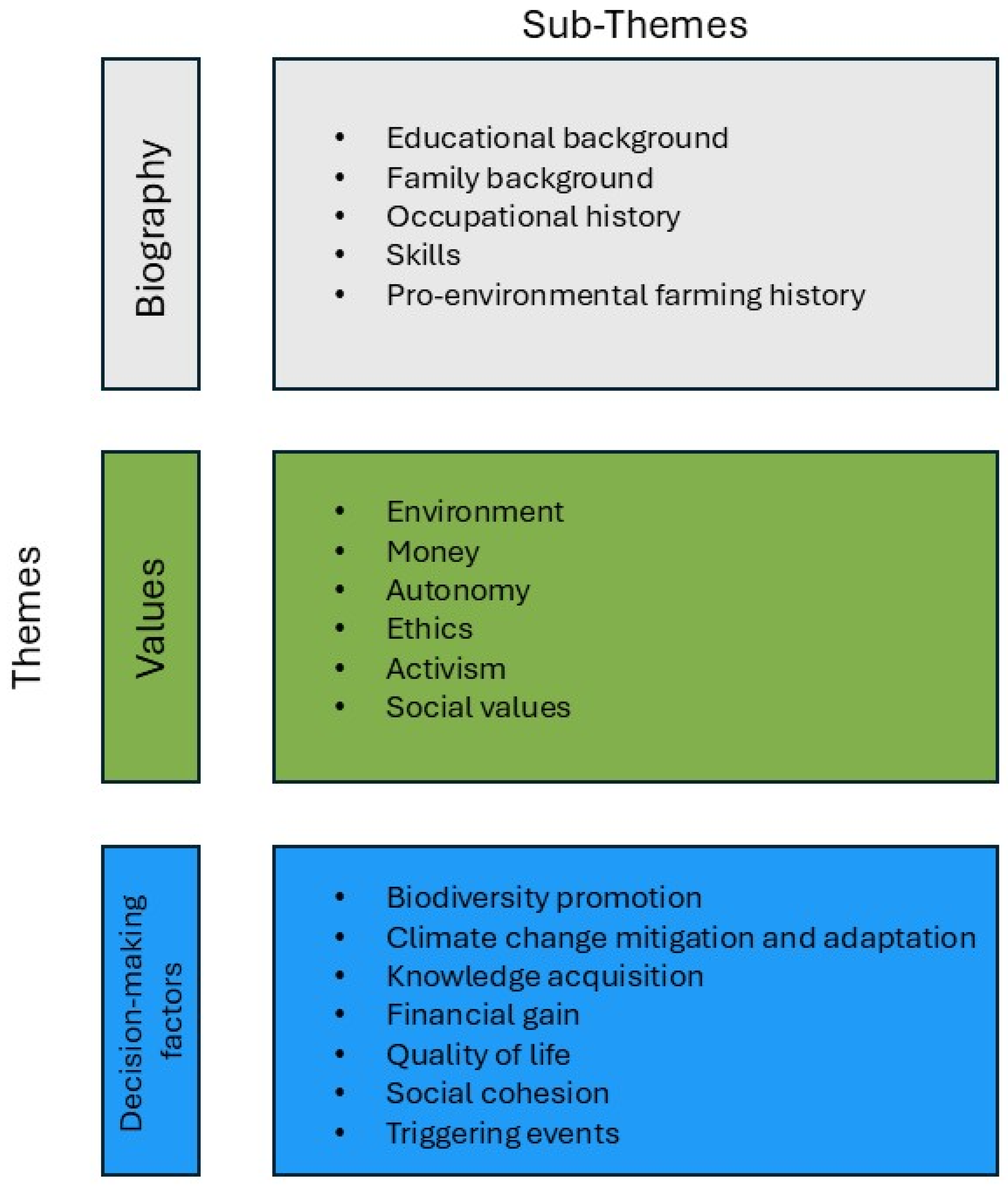

3.1. Conceptual Framework

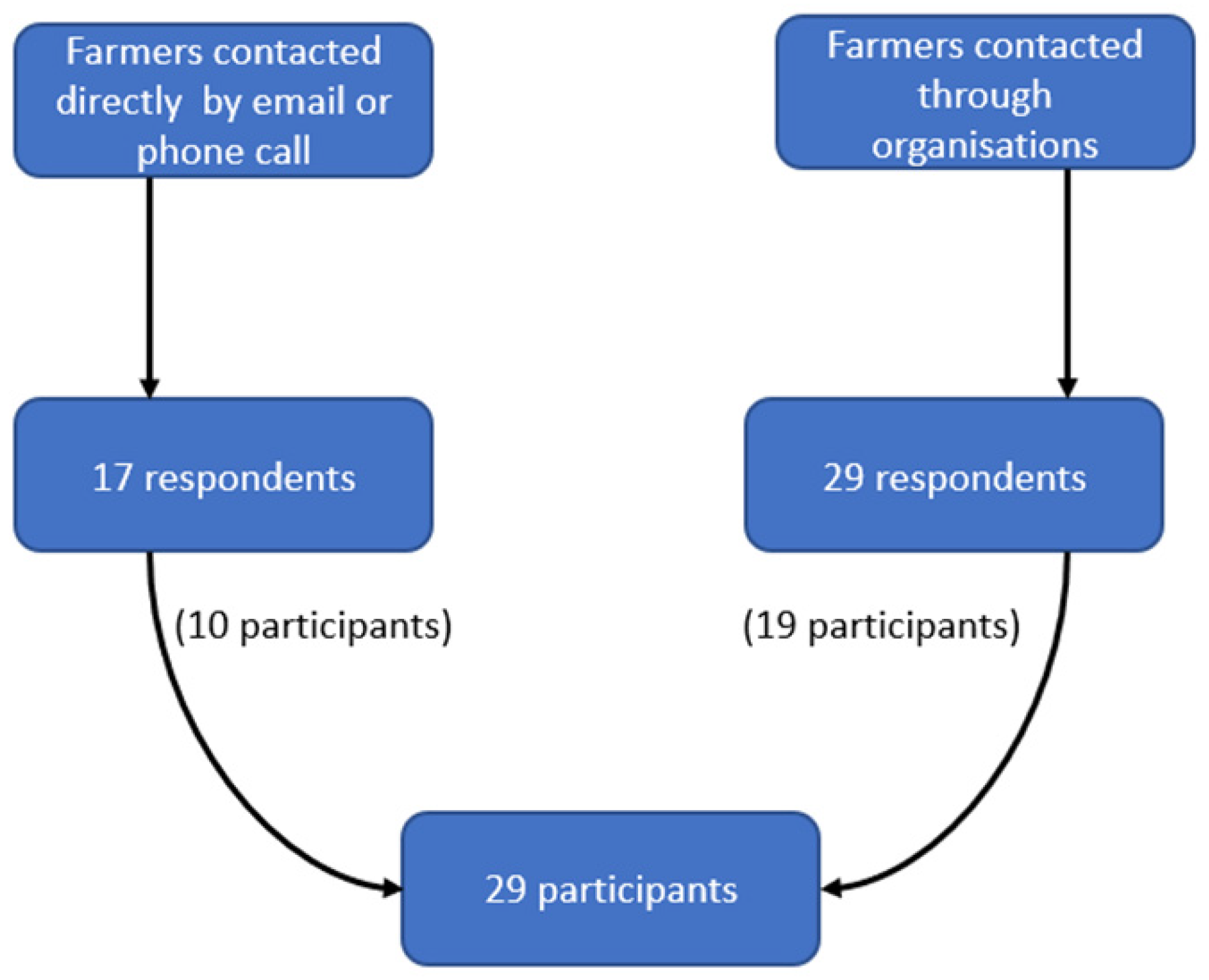

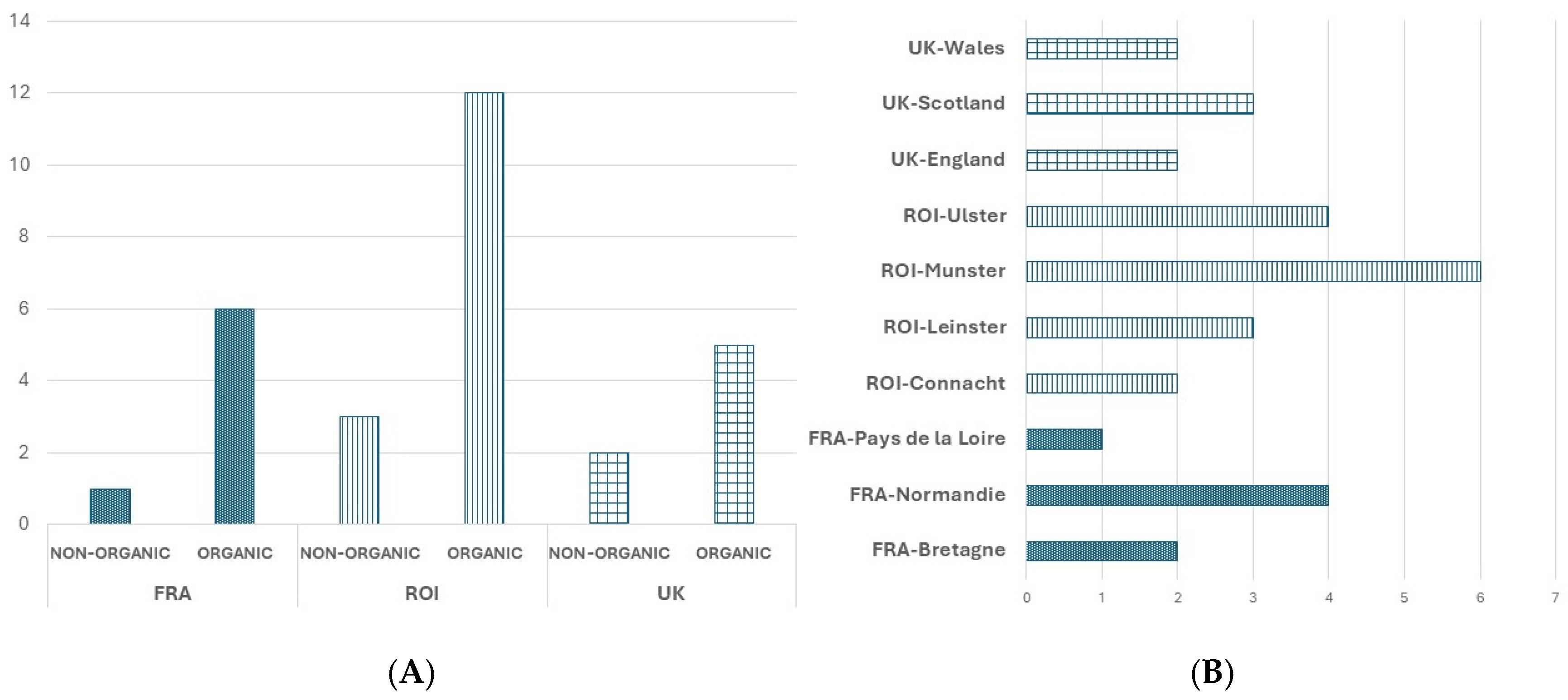

3.2. Methodology

I’m a researcher who is interested in farm diversification, climate change and the environment. Could you tell me the story of your farming experience over the years, all the changes that you have seen and experiences that you have had; how it all has been?

4. Results

4.1. Profitability

When you added in the (pro-environmental) cattle enterprise, the total from the two farming enterprises (cattle and sheep) had grown to about £30,000, which isn’t amazing but at least contributed to our investment. In terms of the return on my time, there had been a vast improvement. We’re actually receiving essentially £30,000 for 40 h a week’s worth of work, which is a much better return than the £12,000 for 80 h a week work that I was doing previously.12A, UK

It’s quite clear that farmers are in a situation where the harder they farm, the more they push for yields, the more fertiliser and feed they buy then the more they are undermining their ability to make a genuine return on their investment; less is more. You have to ease back on all the inputs and that will free up time and resources… and you may need to go and generate some income off farm from doing other things, but it would be a lot better than just pouring money down the drain trying to make the thing stand on its own two feet in a farming sense when it is never going to.30E, UK

We use really simple equipment and we’re really low infrastructure, got hardly any machines, one simple tractor, some simple equipment for haymaking. We started bale grazing last winter, so, you know, rolling out the hay outside so I don’t have to turn the tractor on, we stop the tractor in October and then the hay just sits there all winter, I have to turn it over now and again.4T, FRA

Being self-sufficient doesn’t mean that we’re going to be living away from the people around us, we are autonomous in the territory, at the territory scale. But we don’t want seeds to come from hundreds of kilometres away, we don’t want to be depending on fossil fuel or nuclear energy, and we want to be able to build our tools or fix them by ourselves when necessary and if necessary, we want to be self-sufficient in terms of water, because we know that with climate change, water is going to be the main struggle in the coming years.25X, FRA

If I was selling everything to cooperatives (…) I wouldn’t control my prices, and then they’d say “you have to do this and that”, and they’d say “we need you to produce this much a year”, so then you can’t have two productions, because they want you to have one production, and then you don’t control things.4T, FRA

The other thing is that there are vested interests involved in agriculture and there are quite close relationships between fertiliser companies, seed merchants and all the people providing inputs to farmers, selling machinery and spray machinery, slurry spreaders and all those. There is quite a well-organised system to incentivise, encourage farmers to purchase these things and to use them. I know a lot of commercial farmers who truly believe their grass will not grow without nitrogen. And in some ways they’re right because Italian perennial ryegrass does need nitrogen to grow up but there are lots of other grasses that grew in Ireland for centuries and kept animals alive perfectly well for a very long time that weren’t Italian perennial ryegrass.14W, IE

4.2. Ethical Food Production

(…) there’s a massive disconnect between food and farming. And it is a problem with farmers as much as the general public, like it’s such a shame that lots of farmers don’t have their own meat in their freezers or their own milk.3B, UK

4.3. Conscientisation, Activism and Social Values

It really has been a journey of learning and connecting with nature. For me, going forward, I want to connect more with my local community and enhance biodiversity on the farm and leave that as a legacy for the next generation. We as farmers need to think about other people in society. There are social responsibilities in relation to protecting the soil, biodiversity, water and air.2J, IE

In a city context, you get all these issues thrown in your face… You get this climate change narrative that human beings are bad and should do less bad. If you’re a bit eco-minded like I was, you do everything by bike, get angry at people riding in cars, stop eating meat, things like that… but at some point I realised it wasn’t working and wasn’t making me happy. I wanted to do something more proactive, and I looked for ways to do that but couldn’t find them in the city.30L, FRA

We’re trying to do things right, have clean fields, and inspire our neighbours to do the same and see if this model works. So in this way, we’re activists, for the planet, for our environment, in the face of climate change. As farmers, we work with living things, and so we have to be role models for future generations.12W, FRA

I grew up on a small family dairy farm and all the neighbours had very similar models. I remember silage making time being a serious community effort. I could see all that slipping away as the machinery got bigger and more efficient… but it was really a privilege to witness the power of smaller farms and community integration. I’m not trying to recreate something that’s outdated—it’s just that there’s value in a small farm that adds value to the community.16L, IE

There is a huge opportunity there to raise that awareness, whether, with students or business people, you need to bring them out into nature and engage them by the river bank. I have actually submitted an application to provide training to 14 different communities in my county in 2021 around the rivers. I and a colleague, and hopefully we will engage the local authority waters officer, and maybe some water scientists will really do our best to connect people with our local streams and give them a passion for them.2J, IE

We had a tunnel where we used to grow lettuce; it wasn’t the organic system, it was ordinary sprays. I had the children small at the time. I remember going in one evening after spraying and, just before we planted our lettuce, I said to myself, ‘could this be right’, and the smell took my breath. I said, ‘we have to change this’. So that’s why we changed it.22F, IE

When you’re working with reptiles in captivity you have these terrariums, these enclosures where you recreate an environment. And there are also different functions in their environment, using live plants, so you had to work out the lighting and the ultraviolet, and you had to work out the humidity and so it was really interesting. And then I don’t know what happened but at some point it clicked in me that you could do that on a farm, you can do that sort of thing on a farm!4T, FRA

Being involved in farm walks gave me the confidence to finally change over to organic. I became very impressed with farm walks people. There were only about four or five dairy farmers in the country at the time that were organic. When I visited these farms, what I liked about them the most was that these people were thinking for themselves—how to work with their farm rather than try to change it.21O, IE

4.4. Knowledge Acquisition

I think that if I’d been trained and shaped in a mould, I would’ve followed the trend and would’ve been a conventional farmer. Even what we’re doing now is different to what we did 10 years ago. We’ve evolved towards our goal but we’ve also evolved compared to what we did in the beginning.6A, FRA

You will know about knowledge transfer and organisations who are looking at comparing the economic side as well as the environmental side. My background is IT and that is what I was doing before this. When we started the new dairy enterprise, I had computerised data telling me what each cow was producing. We’ve got reports that will show us what a cow has been producing in the past versus what it is producing now.29G, UK

5. Discussion

5.1. Silent Agroecology

5.2. Agroecological Transition

5.3. Economical Aspects of Agroecology

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Country | Case ID | Farming Type | Farming Enterprise | Gender |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republic of Ireland | 11F | Mixed organic | Beef, lamb | Female |

| 14W | Mixed organic | Beekeeping, crops, lamb | Female | |

| 15D | Organic animal | Beef, lamb | Male | |

| 16L | Organic animal | Beef, lamb | Male | |

| 18R | Organic animal | Beef | Male | |

| 19P | Mixed organic | Beef, crops | Male | |

| 1S | Non-organic animal | Beef, lamb | Male | |

| 21O | Organic animal | Beef | Male | |

| 22F | Mixed organic | Beef, chicken, crops | Female | |

| 27T | Organic animal | Dairy | Female | |

| 28Z | Mixed organic | Beef, crops | Male | |

| 2J | Mixed organic | Beef, crops, pig | Male | |

| 5A | Organic animal | Beef, dairy | Male | |

| 7L | Non-organic animal | Beef, dairy | Male | |

| 8E | Non-organic animal | Beef, dairy | Female | |

| United Kingdom | ||||

| England | 12A | Organic animal | Beef, lamb | Female |

| Wales | 23N | Organic animal | Beef, lamb | Female |

| Scotland | 29G | Organic animal | Dairy | Male |

| England | 30E | Organic animal | Beef | Male |

| Wales | 3B | Mixed organic | Beef, crop, lamb, pig | Female |

| Scotland | 4D | Non-organic animal | Beef, lamb | Male |

| Scotland | 9M | Non-organic mixed | Beef, crops, lamb | Male |

| France | 12W | Mixed organic | Crops, lamb | Male |

| 13N | Mixed organic | Crops, dairy | Female | |

| 25X | Mixed organic | Crops, dairy, chicken | Female | |

| 30L | Mixed organic | Chicken, crops | Male | |

| 4T | Mixed organic | Beef, crops, lamb | Male | |

| 6A | Organic animal | Beef, chicken, lamb, pig | Male | |

| 8F | Organic animal | Beef, chicken | Male | |

References

- Fellmann, T.; Witzke, P.; Weiss, F.; Van Doorslaer, B.; Drabik, D.; Huck, I.; Salputra, G.; Jansson, T.; Leip, A. Major challenges of integrating agriculture into climate change mitigation policy frameworks. Mitig. Adapt. Strat. Glob. Chang. 2018, 23, 451–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanz, B.; Dietz, S.; Swanson, T. The Expansion of Modern Agriculture and Global Biodiversity Decline: An Integrated Assessment. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 144, 260–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. 2019 Refinement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories; Volume 4: Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Use; Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES): Hayama, Japan, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, D.; Kar, S.K.; Chattopadhyay, A.; Rakshit, A.; Tripathi, V.K.; Dubey, P.K.; Abhilash, P.C. Low input sustainable agriculture: A viable climate-smart option for boosting food production in a warming world. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 115, 106412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baste, I.A.; Watson, R.T. Making Peace with Nature: A Scientific Blueprint to Tackle the Climate, Biodiversity and Pollution Emergencies; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Altieri, M.A.; Toledo, V.M. The agroecological revolution in Latin America: Rescuing nature, ensuring food sovereignty and empowering peasants. J. Peasant Stud. 2011, 38, 587–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Ploeg, J.D.; Barjolle, D.; Bruil, J.; Brunori, G.; Madureira, L.M.C.; Dessein, J.; Drąg, Z.; Fink-Kessler, A.; Gasselin, P.; de Molina, M.G.; et al. The economic potential of agroecology: Empirical evidence from Europe. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 71, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wezel, A.; Bellon, S.; Doré, T.; Francis, C.; Vallod, D.; David, C. Agroecology as a science, a movement and a practice. Sustain. Agric. 2009, 2, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Molina, M.G.; Guzmán, G.I. On the Andalusian origins of agroecology in Spain and its contribution to shaping agroecological thought. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2017, 41, 256–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-López, F.; Hernández-Chontal, M.A.; Cisneros-Saguilán, P.; Linares-Gabriel, A. Development of the concept of agroecology in Europe: A review. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliorini, P.; Gkisakis, V.; Gonzalvez, V.; Raigón, M.D.; Bàrberi, P. Agroecology in mediterranean Europe: Genesis, state and perspectives. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gliessman, S. Agroecology: Growing the roots of resistance. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2013, 37, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraine, M.; Duru, M.; Nicholas, P.; Leterme, P.; Therond, O. Farming system design for innovative crop-livestock integration in Europe. Animal 2014, 8, 1204–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosset, P.M.; Altieri, M.A. Agroecology: Science and Politics; Practical Action Publishing: Rugby Warwichshire, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wezel, A.; Goette, J.; Lagneaux, E.; Passuello, G.; Reisman, E.; Rodier, C.; Turpin, G. Agroecology in Europe: Research, education, collective action networks, and alternative food systems. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, J. Availability of disaggregated greenhouse gas emissions from beef cattle production: A systematic review. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2019, 76, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielcarek-Bocheńska, P.; Rzeźnik, W. Greenhouse Gas Emissions from agriculture in EU countries—State and perspectives. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Country Factsheets: France; DG AGRI—EUROSTAT: Brussels. 2023; Available online: https://agridata.ec.europa.eu/extensions/CountryFactsheets/CountryFactsheets.html?memberstate=France (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Qi, A.; Whatford, L.; Payne-Gifford, S.; Cooke, R.; Van Winden, S.; Häsler, B.; Barling, D. Can 100% Pasture-Based Livestock Farming Produce Enough Ruminant Meat to Meet the Current Consumption Demand in the UK? Grasses 2023, 2, 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mićić, G.; Rokvić-Knežić, G.; Đurić, G.; Marković, D. Transition from conventional to agroecological systems, case study of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Ekon. Poljopr. 2022, 69, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutcheson, M.; Morton, A.; Blair, S. Actualizations of agroecology among Scottish farmers. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 48, 50–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagunga, G.; Ayamga, M.; Laube, W.; Ansah, I.G.K.; Kornher, L.; Kotu, B.H. Agroecology and resilience of smallholder food security: A systematic review. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1267630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, R.B.; Liebert, J.; Kansanga, M.; Kpienbaareh, D. Human and social values in agroecology: A review. Elementa Sci. Anthr. 2022, 10, 00090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacombe, C.; Couix, N.; Hazard, L. Designing agroecological farming systems with farmers: A review. Agric. Syst. 2018, 165, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, C.I.; Altieri, M.A. Pathways for the amplification of agroecology. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2018, 42, 1170–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoonhoven, Y.; Runhaar, H. Conditions for the adoption of agro-ecological farming practices: A holistic framework illustrated with the case of almond farming in Andalusia. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2018, 16, 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-García, D.; Carrascosa-García, M. Agroecology-oriented farmers’ groups. A missing level in the construction of agroecology-based local agri-food systems? Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 47, 996–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, P.D.; Rose, D.C.; Burgess, P.J.; Staley, J.T. Barriers and Enablers to Uptake of Agroecological and Regenerative Farming Practices, and Stakeholder Views About “Living Labs”; Report from the “Evaluating the productivity, environmental sustainability and wider impacts of agroecological compared to conventional farming systems”; Cranfield University and UK Centre for Ecology and Hydrology: Cranfield, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wengraf, T. Qualitative Research Interviewing; SAGE Publications, Ltd.: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochner, A.; Ellis, C. Evocative Autoethnography; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascuel-Odoux, C.; Lescourret, F.; Dedieu, B.; Detang-Dessendre, C.; Faverdin, P.; Hazard, L.; Litrico-Chiarelli, I.; Petit, S.; Roques, L.; Reboud, X.; et al. A research agenda for scaling up agroecology in European countries. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 42, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalek, J. Environmental and Farm Impacts of the EU RDP Agri-Environmental Measures: Evidence from Slovak Regions. Land Use Policy 2022, 113, 105924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louhichi, K.; Ciaian, P.; Espinosa, M.; Colen, L.; Perni, A.; Paloma, S.G.Y. Does the crop diversification measure impact EU farmers’ decisions? An assessment using an Individual Farm Model for CAP Analysis (IFM-CAP). Land Use Policy 2017, 66, 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakner, S.; Kirchweger, S.; Hoop, D.; Brümmer, B.; Kantelhardt, J. The Effects of diversification activities on the technical efficiency of organic farms in Switzerland, Austria, and Southern Germany. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uehleke, R.; Petrick, M.; Hüttel, S. Evaluations of agri-environmental schemes based on observational farm data: The importance of covariate selection. Land Use Policy 2022, 114, 105950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Scaling Up Agroecology to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals, Proceedings of the Second FAO International Symposium, 3–5 April 2018, Rome, Italy; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019; ISBN 978-92-5-131332-9. [Google Scholar]

- High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition (HLPE). Agroecological and Other Innovative Approaches for Sustainable Agriculture and Food Systems That Enhance Food Security and Nutrition; High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.C.; Harrison, P.A.; Leach, N.J.; Godfray, H.C.J.; Hall, J.W.; Jones, S.M.; Gall, S.S.; Obersteiner, M. Sustainable pathways towards climate and biodiversity goals in the UK: The importance of managing land-use synergies and trade-offs. Sustain. Sci. 2023, 18, 521–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westaway, S.; Grange, I.; Smith, J.; Smith, L.G. Meeting tree planting targets on the UK’s path to net-zero: A review of lessons learnt from 100 years of land use policies. Land Use Policy 2023, 125, 106502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willer, H.; Trávníček, J.; Schlatter, B. The World of Organic Agriculture Statistics & Emerging Trends 2024; Research Institute of Organic Agriculture FiBL: Frick, Switzerland; IFOAM—Organics International: Bonn, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lantremange, H.; Magrini, M.-B.; Frayssignes, J.; Fortun-Lamothe, L.; Lauri, P.-É.; Lebret, B.; Le Gouis, J. Nurturing niche innovations by agrifood value chains in transition to agroecology: A qualitative analysis through eleven case studies in France. In Proceedings of the 14th International Sustainability Transitions Conference: Responsibility and Reflexivity in Transitions, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 30 August–1 September 2023; HAL Open Science: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sollen-Norrlin, M.; Ghaley, B.B.; Rintoul, N.L.J. Agroforestry benefits and challenges for adoption in Europe and beyond. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macken-Walsh, Á.; Buckley, C.; Dillon, E.; Hyland, J. Scoping Study: Data Collection Requirements to Inform Strategies for Sustainable Agriculture at Farm-Level; Climate Change Advisory Council: Dublin, Ireland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Buratti-Donham, J.; Venn, R.; Schmutz, U.; Migliorini, P. Transforming food systems towards agroecology—A critical analysis of agroforestry and mixed farming policy in 19 European countries. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 47, 1023–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, L.; Kendall, H.; Hansda, R.; Reed, M.; Williams, D. Identifying economic and societal drivers of engagement in agri-environmental schemes for English dairy producers. Land Use Policy 2021, 101, 105174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baaken, M.C. Sustainability of agricultural practices in Germany: A literature review along multiple environmental domains. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2022, 22, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney, S.; Carter, A.; Hynds, P.; Macken-Walsh, Á.; Henchion, M.; Devereux, E.; Markiewicz-Kęszycka, M. On-farm pro-environmental diversification: A qualitative analysis of narrative interviews with Western-European farmers. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 48, 93–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroney, A.; O’Reilly, S.; O’Shaughnessy, M. Taking the Leap and Sustaining the Journey: Diversification on the Irish Family Farm. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2016, 6, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Rourke, E.; Charbonneau, M.; Poinsot, Y. High nature value mountain farming systems in Europe: Case studies from the Atlantic Pyrenees, France and the Kerry Uplands, Ireland. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 46, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, L.-A.; Toma, L.; Barnes, A.P.; Matthews, K.B.; Hopkins, J. Agri-environmental diversification: Linking environmental, forestry and renewable energy engagement on Scottish farms. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plateau, L.; Roudart, L.; Hudon, M.; Maréchal, K. Opening the organisational black box to grasp the difficulties of agroecological transition. An empirical analysis of tensions in agroecological production cooperatives. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 185, 107048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Ploeg, J.D.; Schneider, S. Autonomy as a politico-economic concept: Peasant practices and nested markets. J. Agrar. Chang. 2022, 22, 529–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Molina, M.G.; Petersen, P.F.; Peña, F.G.; Caporal, F.R. Political Agroecology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Ploeg, J.D. The New Peasantries: Rural Development in Times of Globalization, 2nd ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Milone, P.; Ventura, F. New generation farmers: Rediscovering the peasantry. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 65, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Ploeg, J.D. Peasantry in the Twenty-First Century. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; Volume 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, V. A “silent” agroecology: The significance of unrecognized sociotechnical changes made by French farmers. Rev. Agric. Food Environ. Stud. 2021, 102, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelman, M.; Borras, S.M., Jr. Political Dynamics of Transnational Agrarian Movements; Agrarian Change and Peasant Studies Series; Fernwood Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-55266-817-7. [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Giménez, E.; Altieri, M.A. Agroecology, food sovereignty and the new green revolution. J. Sustain. Agric. 2013, 37, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaruk, D. Is agroecology a solution or an agenda? Outlook Agric. 2023, 52, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbally, M.; O’neill, C.S. An introduction to the biographical narrative interpretive method. Nurse Res. 2014, 21, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAloon, C.G.; Macken-Walsh, Á.; Moran, L.; Whyte, P.; More, S.J.; O’grady, L.; Doherty, M.L. Johne’s disease in the eyes of Irish cattle farmers: A qualitative narrative research approach to understanding implications for disease management. Prev. Veter.-Med. 2017, 141, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peta, C.; Wengraf, T.; McKenzie, J. Facilitating the voice of disabled women: The biographic narrative interpretive method (BNIM) in action. Contemp. Soc. Sci. 2019, 14, 515–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandelowski, M. Focus on research methods: Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res. Nurs. Health 2000, 23, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, C.; Atkinson, S.; Doody, O. Employing a Qualitative Description Approach in Health Care Research. Glob. Qual. Nurs. Res. 2017, 4, 2333393617742282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flyvbjerg, B. Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research. In Qualitative Research Practice; Seale, C., Gobo, G., Gubrium, J.F., Silverman, D., Eds.; Sage: London, UK; Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 420–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starman, A.B. The Case Study as a Type of Qualitative Research. J. Contemp. Educ. Stud. 2013, 1, 28–43. [Google Scholar]

- Schwandt, T.A.; Gates, E.F. Case Study Methodology. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research, 5th ed.; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017; pp. 341–354. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. What can “thematic analysis” offer health and wellbeing researchers? Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Wellbeing 2014, 9, 26152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, W.F.; Lokhorst, A.M.; Berendse, F.; de Snoo, G.R. Factors underlying farmers’ intentions to perform unsubsidised agri-environmental measures. Land Use Policy 2016, 59, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammes, V.; Eggers, M.; Isselstein, J.; Kayser, M. The attitude of grassland farmers towards nature conservation and agri-environment measures—A survey-based analysis. Land Use Policy 2016, 59, 528–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unay-Gailhard, I.; Bojnec, Š. Sustainable participation behaviour in agri-environmental measures. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 138, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, A.; Britz, W. European farms’ participation in agri-environmental measures. Land Use Policy 2016, 50, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, H.M.; Berg, L.V.D.; Cardoso, I.M.; Vermue, A.J.; Bianchi, F.J.J.A.; Peña-Claros, M.; Tittonell, P. Understanding farm diversity to promote agroecological transitions. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, T.; Gressier, C. Australia’s new peasantry: Towards a politics and practice of custodianship on agroecology-oriented farms. J. Peasant Stud. 2025, 25, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niska, M.; Vesala, H.T.; Vesala, K.M. Peasantry and Entrepreneurship as Frames for Farming: Reflections on Farmers’ Values and Agricultural Policy Discourses. Sociol. Rural 2012, 52, 453–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zechner, M.; Zentgraf, L.L.; Hansen, B.R. Farming and Its Others, and Other Ways of Farming. Why So Many Farmers Are Raging Against the Conditions of Food Production, and What Other Farmers We Should Look to for Alternatives. Common Ecologies. 2024. Available online: https://commonecologies.net/farming-and-its-others/ (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Burton, R.J. Seeing Through the ‘good farmer’s’ eyes: Towards developing an understanding of the social symbolic value of ‘productivist’ behaviour. Sociol. Rural 2004, 44, 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittenzwei, K.; Lien, G.; Fjellstad, W.; Øvren, E.; Dramstad, W. Effects of landscape protection on farm management and farmers’ income in Norway. J. Environ. Manag. 2010, 91, 861–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, L.; Burton, R.J. Good farmers, good neighbours? The role of cultural capital in social capital development in a Scottish farming community. Sociol. Rural 2011, 51, 238–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvet-Mir, L.; de Amézaga, R.; Buller, H.; Laville, C. The Contribution of Traditional Agroecological Knowledge as a Digital Commons to Agroecological Transitions: The Case of the CONECT-e Platform. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, S. Collaboration for Local Food Systems: The Role of Government in Supporting and Fostering Conditions for Successful Local Food System Collaboration in Dublin, Ireland. Master’s Thesis, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Alexopoulos, G.; Koutsouris, A.; Tzouramani, I. Should I stay or should I go? Factors affecting farmers’ decision to convert to organic farming as well as to abandon it. In Proceedings of the 9th European IFSA Symposium—Building Sustainable Rural Future: The Added Value of Systems Approaches in Times of Change and Uncertainty, Vienna, Austria, 4–7 July 2010; pp. 1083–1093. [Google Scholar]

- Sroka, W.; Dudek, M.; Wojewodzic, T.; Król, K. Generational changes in agriculture: The influence of farm characteristics and socio-economic factors. Agriculture 2019, 9, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, T. Farmer engagement: An essential policy tool for delivering environmental management on farmland. Asp. Appl. Biol. 2013, 118, 187–191. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, A.W.; Reimer, A.; Prokopy, L.S. Farmers’ Views of the Environment: The Influence of Competing Attitude Frames on Landscape Conservation Efforts. Agric. Hum. Values 2015, 32, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, W.; Bosworth, G.; Ruto, E. Entrepreneurial Younger Farmers and the “Young Farmer Problem” in England. J. Agric. For. 2015, 61, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wreford, A.; Ignaciuk, A.; Gruère, G. Overcoming Barriers to the Adoption of Climate-Friendly Practices in Agriculture; OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Paper 101; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darlot, M.; Anglade, J.; Maïzi, P.M.; Lamine, C.; Rengard, F.; Iceri, V.; Genay, A.; Celis, C. Teaching, training and learning for the agroecological transition: A French-Brazilian perspective. In Agroecological Transitions, Between Determinist and Open-Ended Visions; Lamine, C., Magda, D., Rivera-Ferre, M., Marsden, T., Eds.; Peter Lang: Brussels, Belgium, 2021; Volume EcoPolis 37. [Google Scholar]

- Zagata, L.; Sutherland, L.-A. Deconstructing the ‘young farmer problem in Europe’: Towards a research agenda. J. Rural Stud. 2015, 38, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galliano, D.; Siqueira, T.T. Organizational design and environmental performance: The case of French dairy farms. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 278, 111408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M.; van de Vijver, F.J.R. Factorial Structure of the Family Values Scale from a Multilevel-Multicultural Perspective. Int. J. Test. 2014, 14, 168–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkness, C.; Areal, F.J.; Semenov, M.A.; Senapati, N.; Shield, I.F.; Bishop, J. Stability of Farm Income: The Role of Agricultural Diversity and Agri-Environment Scheme Payments. Agric. Syst. 2021, 187, 103009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azima, S.; Mundler, P. Does direct farm marketing fulfill its promises? analyzing job satisfaction among direct-market farmers in Canada. Agric. Hum. Values 2022, 39, 791–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera, M.; Guarín, A.; Pinto-Correia, T.; Almaas, H.; Mur, L.A.; Burns, V.; Czekaj, M.; Ellis, R.; Galli, F.; Grivins, M.; et al. Assessing the role of small farms in regional food systems in Europe: Evidence from a comparative study. Glob. Food Secur. 2020, 26, 100417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Aspect | Agroecology | New Peasantry |

|---|---|---|

| Core principles | Sustainable use of local resources; biodiversity for ecosystem services and resilience; participatory, transdisciplinary research; and solutions providing environmental, economic, and social benefits. | Farming with autonomy, resilience; deliberate resistance to industrialised agriculture, working with rather than against nature, providing diversity of product to local markets, mutual support; reduced inputs. |

| Social and Political Goals | Advocating for food sovereignty, defending family farms and smallholder agriculture, promoting local markets, and resisting the dominant industrial agri-food system. | Resistance to industrialised agriculture, focus on local solutions to global challenges, and deliberate innovation for socio-economic autonomy. |

| Scale and Scope | Holistic focus on the entire food system, from soil management to societal organisation, aiming to integrate environmental, economic, and social dimensions at multiple scales (local to global). | Primarily focused on farm-level autonomy and community resilience, with implications for broader socio-political resistance against the global industrialised food system. |

| Relationship to Environment | Co-production with nature to maintain balance. Use of local renewable resources and biodiversity to enhance ecosystem services and resilience. Holistic approach connecting soil, ecosystems, and communities. | Co-production with nature; emphasis on autonomy over resources (land, fertility, labour, capital). Resistance to dominant agri-food systems through local and low-input solutions. |

| Agency and Motivation | A movement driven by collective action, advocacy, and principles of sustainability, equity, and justice in food systems. | Individual and collective agency rooted in “tenacity” and “stubbornness,” driven by belief in capacity to resist, adapt, and innovate within the constraints of industrialised agriculture. |

| Education and Knowledge | Emphasises participatory, transdisciplinary, and action-research methods. Promotes diverse knowledge systems, including indigenous and scientific methods. | Integration of traditional farming knowledge with modern innovations. Collaboration with diverse actors to innovate and adapt to challenges. Sharing knowledge through cooperation and reciprocity in communities. |

| Variable | Variable Categories | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Country | Republic of Ireland | 15 (52) |

| United Kingdom | 7 (24) | |

| France | 7 (24) | |

| Gender | Male | 19 (66) |

| Female | 10 (35) | |

| Age | 26–35 years | 3 (10) |

| 36–45 years | 8 (28) | |

| 46–55 years | 9 (31) | |

| 56–65 years | 5 (17) | |

| >66 years | 4 (14) | |

| Education | Junior Certificate or GCSEs (FR. Brevet) | 2 (7) |

| Leaving Certificate or A-Levels (Baccalauréat) | 2 (7) | |

| Higher Certificate or Diploma (Baccalauréat Professionnel) | 6 (21) | |

| Third Level Bachelor’s Degree (Licence) | 10 (35) | |

| Postgraduate Degree Masters or PhD | 9 (31) | |

| No. years in farming | 1–10 years | 19 (66) |

| 11–20 years | 4 (14) | |

| >20 years | 6 (21) | |

| No. years organic farming | 1–10 years | 13 (52) |

| 11–20 years | 4 (16) | |

| >20 years | 8 (32) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Markiewicz-Keszycka, M.; Macken-Walsh, Á.; Carter, A.; Mooney, S.; Devereux, E.J.; Henchion, M.; Hynds, P. Farmers’ Experiences of Transitioning Towards Agroecology: Narratives of Change in Western Europe. Agriculture 2025, 15, 625. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15060625

Markiewicz-Keszycka M, Macken-Walsh Á, Carter A, Mooney S, Devereux EJ, Henchion M, Hynds P. Farmers’ Experiences of Transitioning Towards Agroecology: Narratives of Change in Western Europe. Agriculture. 2025; 15(6):625. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15060625

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarkiewicz-Keszycka, Maria, Áine Macken-Walsh, Aileen Carter, Simon Mooney, Emma J. Devereux, Maeve Henchion, and Paul Hynds. 2025. "Farmers’ Experiences of Transitioning Towards Agroecology: Narratives of Change in Western Europe" Agriculture 15, no. 6: 625. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15060625

APA StyleMarkiewicz-Keszycka, M., Macken-Walsh, Á., Carter, A., Mooney, S., Devereux, E. J., Henchion, M., & Hynds, P. (2025). Farmers’ Experiences of Transitioning Towards Agroecology: Narratives of Change in Western Europe. Agriculture, 15(6), 625. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15060625