Energy Consumption Assessment of a Tractor Pulling a Five-Share Plow During the Tillage Process

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Tractor Plow Experiment Evaluating Energy Consumption

2.1. Tractor Introduction

2.2. Measurement Method

- (1)

- Diesel engine parameters

- (2)

- Vehicle parameters

- (3)

- Farm tool parameters

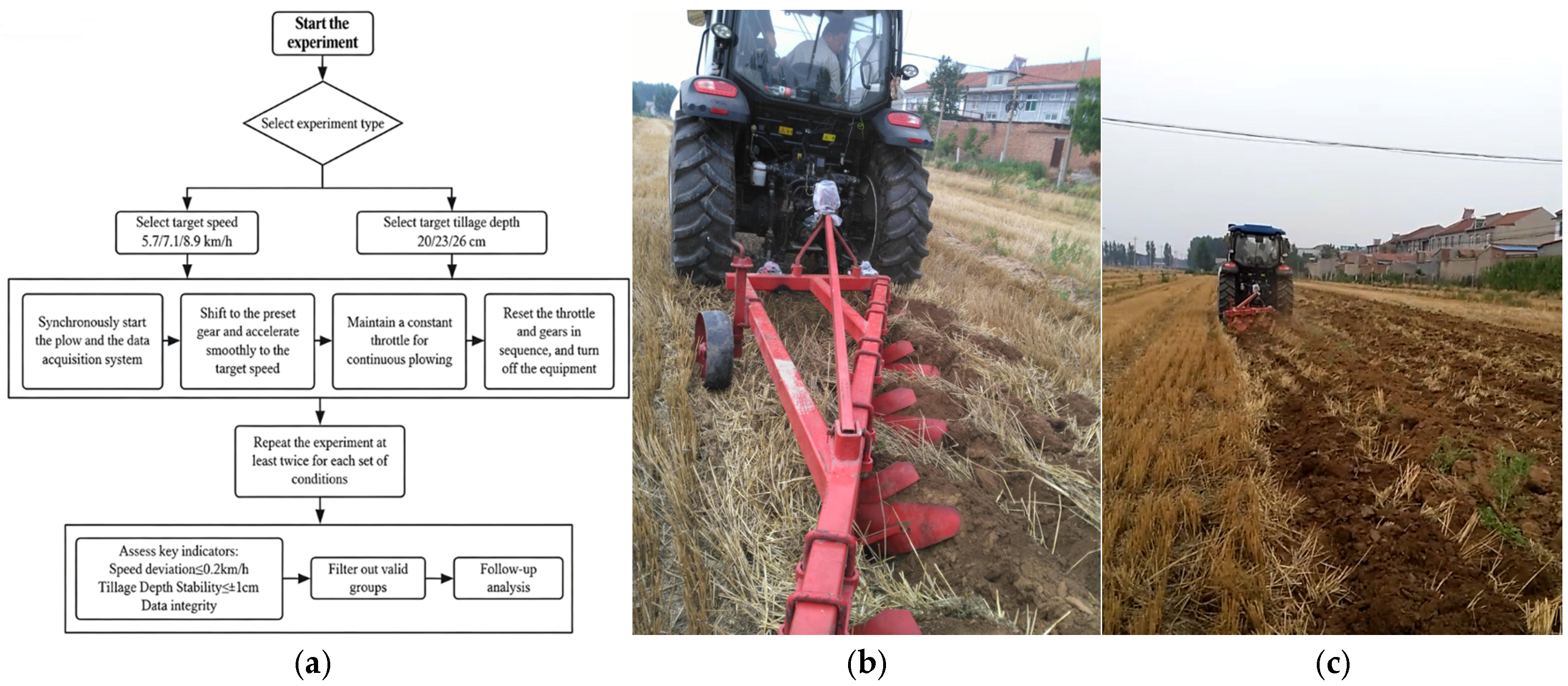

2.3. Experiment Procedures

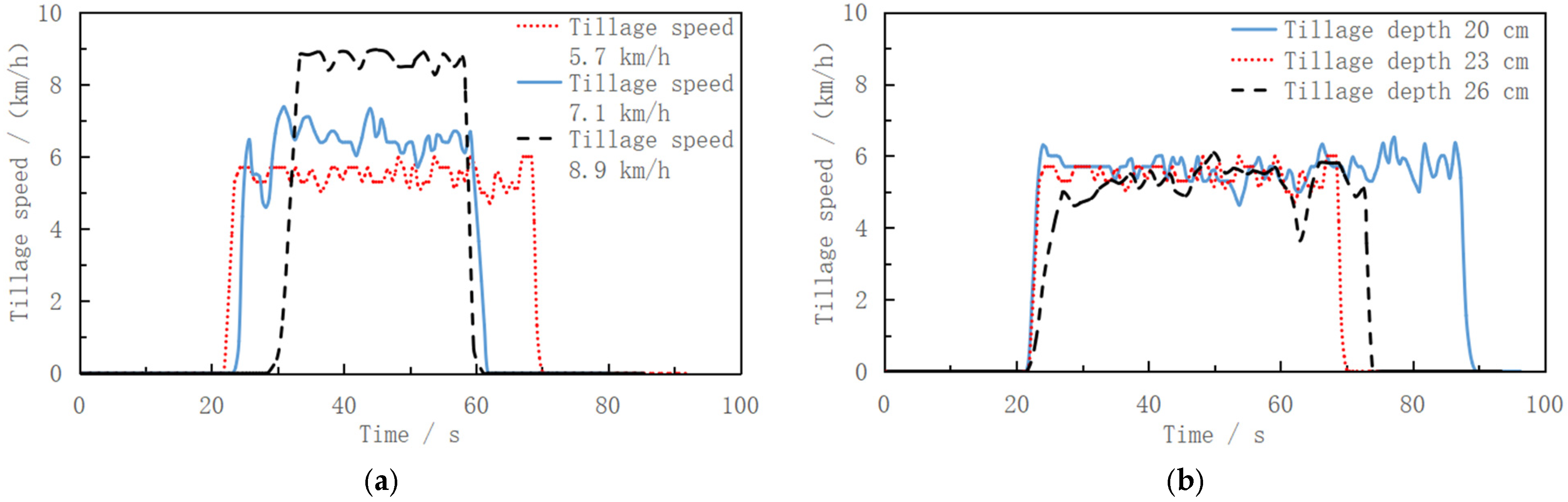

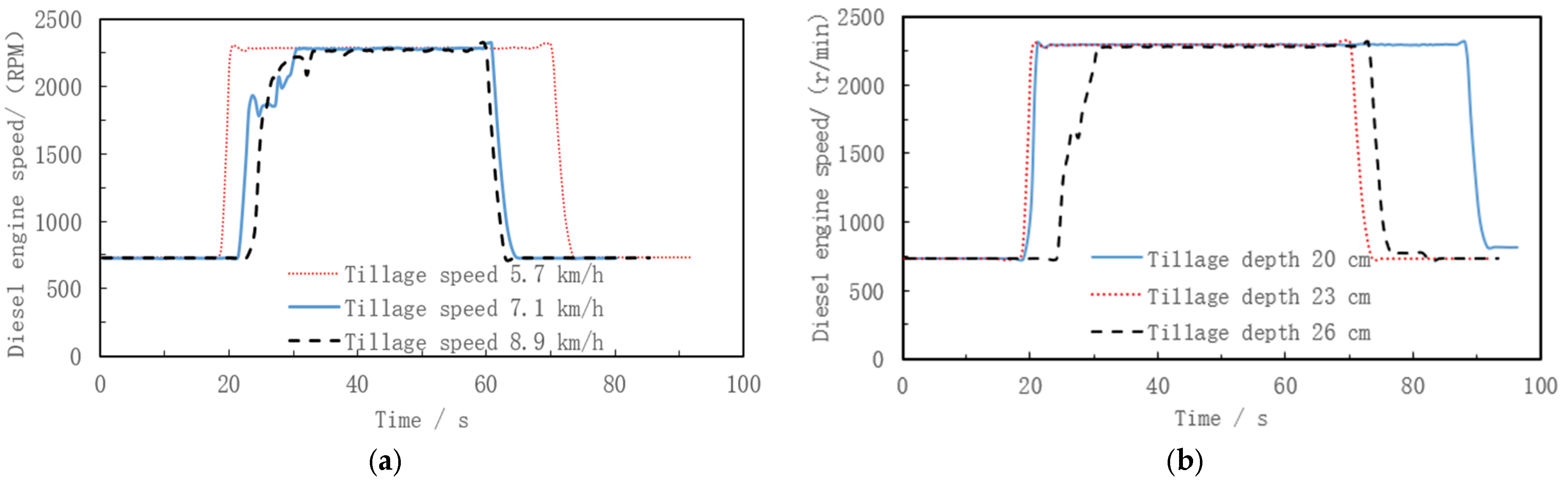

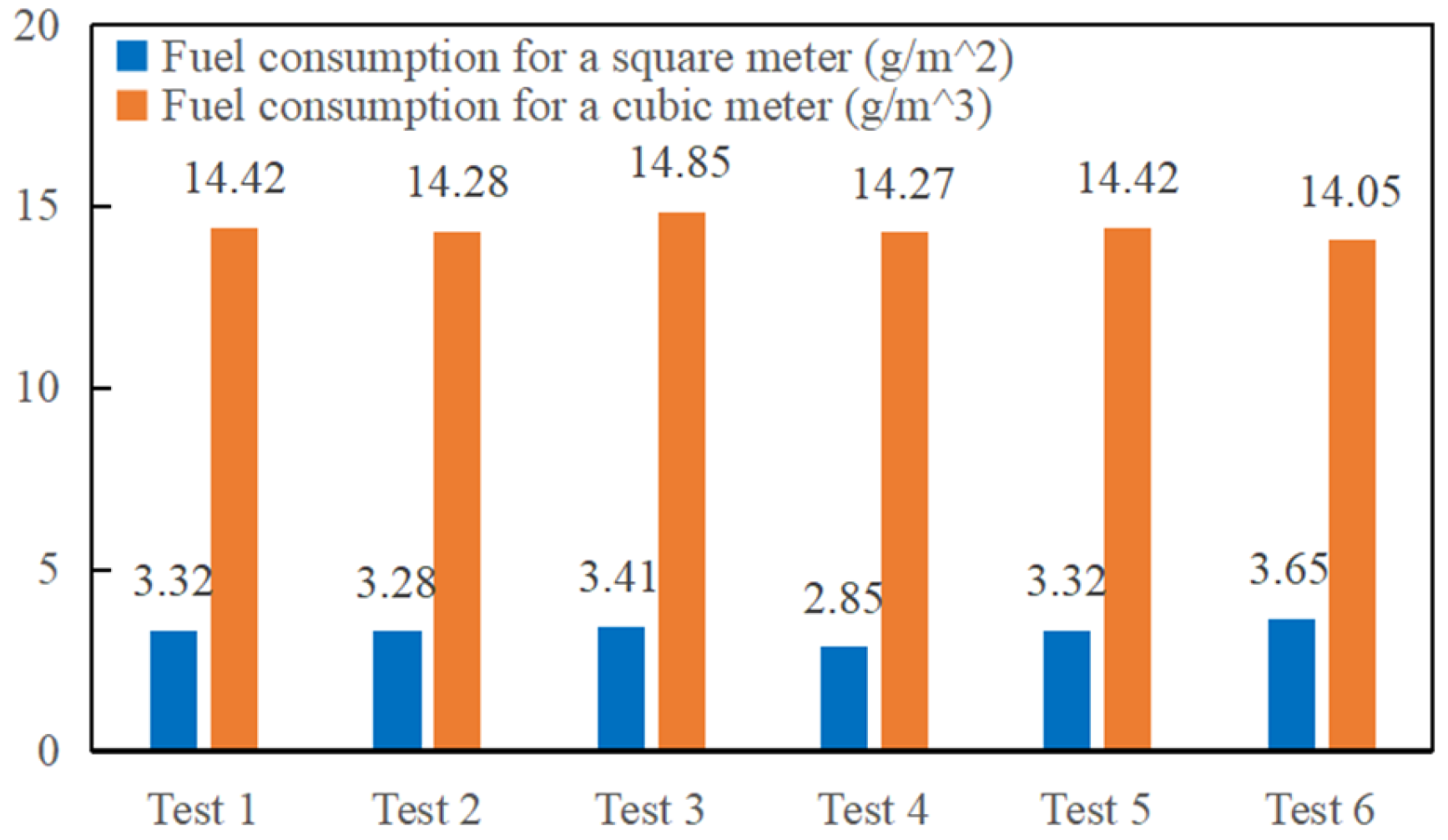

3. Experiment Results

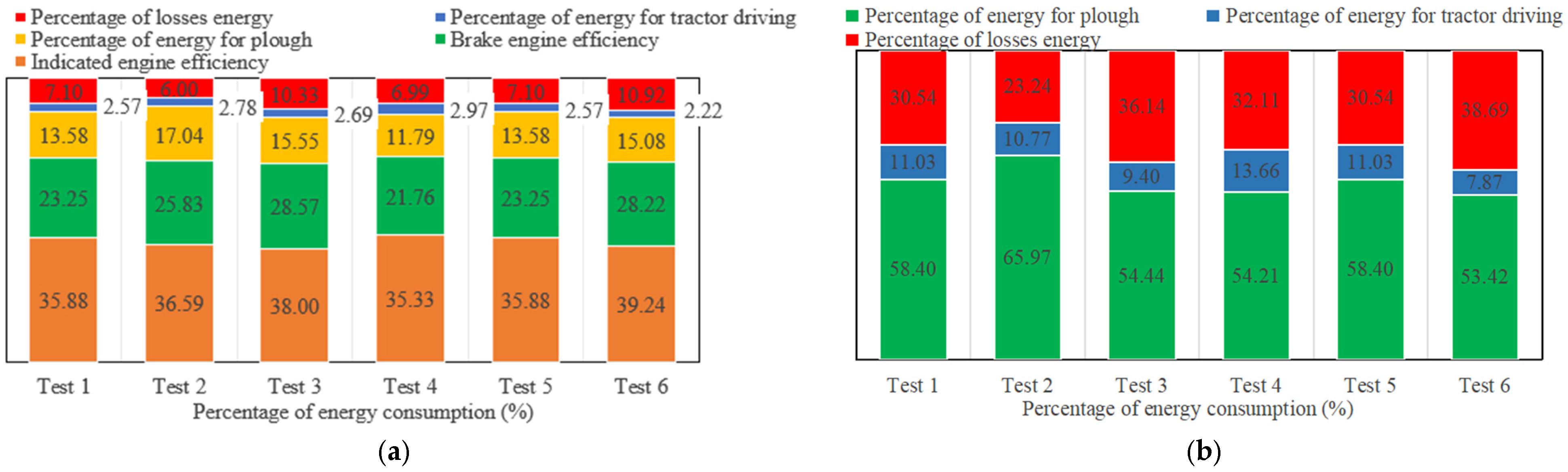

4. Discussion

- (1)

- The energy flow of the tractor

- (2)

- The energy consumption for tractor plowing

- (3)

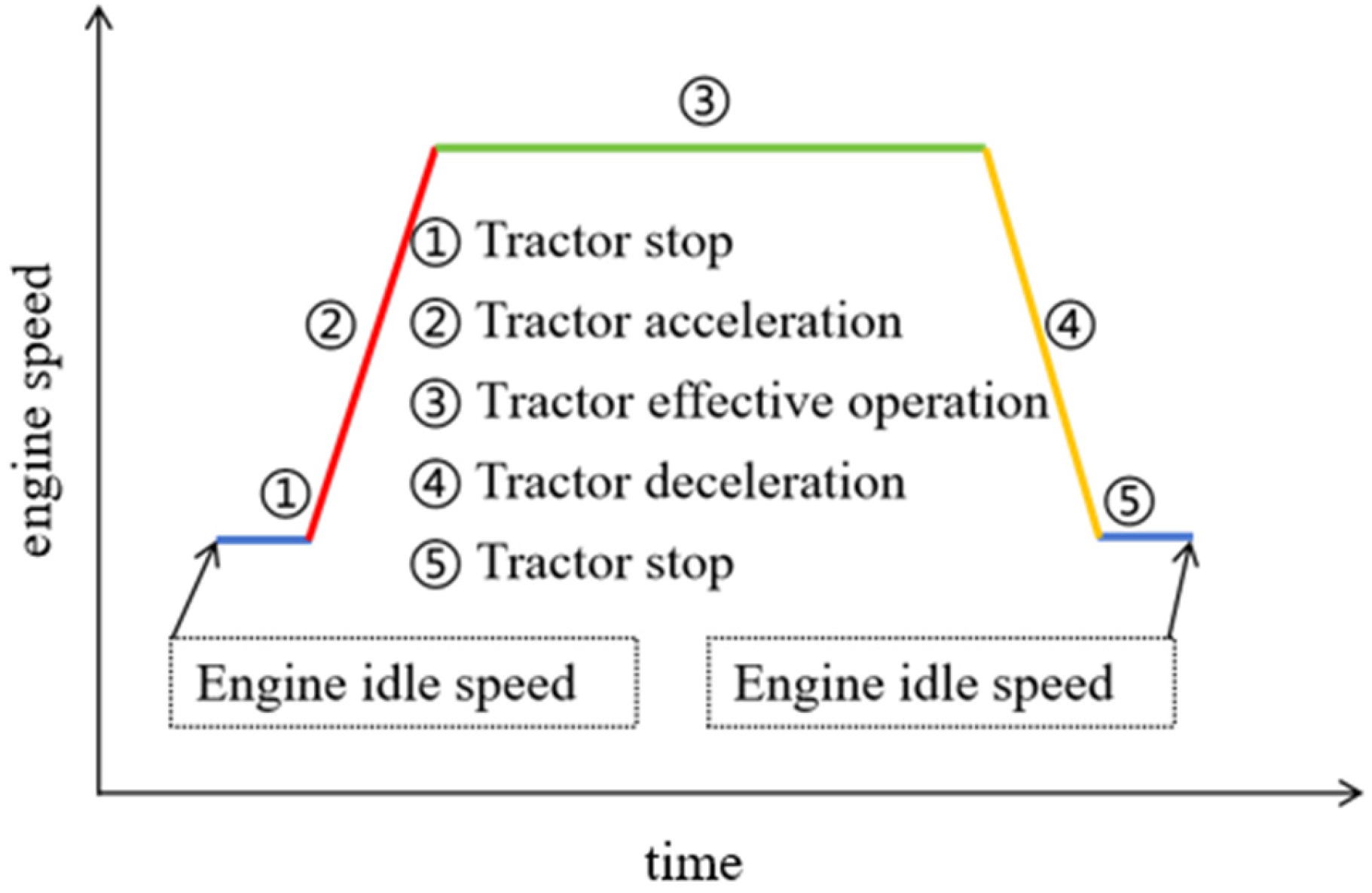

- Division of Cultivation Stages and Fuel Consumption Characteristics

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Under fixed conditions, such as the tractor gear, the accelerator pedal, and the plowing depth, most of the performance parameters of the tractor still fluctuate significantly. It can be seen that the transient state is the normal state during the tractor’s field operation.

- (2)

- Based on fuel energy, the brake thermal efficiency of diesel engines ranges from 21.76% to 28.57%, while the energy consumed for plowing ranges from about 11.79% to 17.04%. It can be seen that there is considerable potential for engine performance optimization.

- (3)

- Based on the engine output power, the plowing operation consumes approximately 53.42% to 65.97% of the energy, but there is also a loss of 23.24% to 38.69% of energy. It can be seen that the transmission losses are worthy of optimization.

- (4)

- Plowing speed has minimal impact on fuel consumption per unit area, while plowing depth significantly affects fuel consumption per unit area. The plowing fuel consumption per cubic meter of soil is nearly unaffected by both plowing speed and depth.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Han, J.; Yan, X.; Tang, H. Method of controlling tillage depth for agricultural tractors considering engine load characteristics. Biosyst. Eng. 2023, 227, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janulevicius, A.; Juostas, A.; Pupinis, G. Tractor’s engine performance and emission characteristics in the process of ploughing. Energy Convers. Manag. 2013, 75, 498–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karparvarfard, S.H.; Rahmanian-Koushkaki, H. Development of a fuel consumption equation: Test case for a tractor chisel-ploughing in a clay loam soil. Biosyst. Eng. 2015, 130, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moitzi, G.; Haas, M.; Wagentristl, H.; Boxberger, J.; Gronauer, A. Energy consumption in cultivating and ploughing with traction improvement system and consideration of the rear furrow wheel-load in ploughing. Soil Tillage Res. 2013, 134, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Md-Tahir, H.; Zhang, J.; Xia, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, H.; Du, J.; Sultan, M.; Mamona, H. Experimental Investigation of Traction Power Transfer Indices of Farm-Tractors for Efficient Energy Utilization in Soil Tillage and Cultivation Operations. Agronomy 2021, 11, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, W.; Baek, S.; Baek, S.; Kim, Y.; Lee, S.; Kim, Y. Analysis of Tillage Depth and Gear Selection for Mechanical Load and Fuel Efficiency of an Agricultural Tractor Using an Agricultural Field Measuring System. Sensors 2020, 20, 2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, W.; Siddique, M.A.A.; Baek, S.; Baek, S.; Cheon, S.; Lee, S.; Lee, K.; Hong, D.; Park, S.; et al. Power Transmission Efficiency Analysis of 42 kW Power Agricultural Tractor According to Tillage Depth during Moldboard Plowing. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Lee, S.; Baek, S.; Baek, S.; Jeon, H.; Lee, J.; Kim, W.; Shim, J.; Kim, Y. Analysis of the Effect of Tillage Depth on the Working Performance of Tractor-Moldboard Plow System under Various Field Environments. Sensors 2022, 22, 2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakahy, A.N.N.; Alshamary, W.F.A.; Kakei, A.A. The Impact of Forward Tractor Speed and Depth of Ploughing in Some Soil Physical Properties. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 761, 12002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Kim, Y.; Park, S.; Kim, Y. Influence of soil moisture content on the traction performance of a 78-kW agricultural tractor during plow tillage. Soil Tillage Res. 2021, 207, 104851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moinfar, A.; Shahgholi, G.; Gilandeh, Y.A.; Gundoshmian, T.M. The effect of the tractor driving system on its performance and fuel consumption. Energy 2020, 202, 117803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim Kareem, K.; Sven, P. Effect of Ploughing Depth, Tractor Forward Speed, and Plough Types on the Fuel Consumption and Tractor Performance. Polytechnic 2019, 9, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Ren, B.; Wu, J.; Hu, J.; Fu, J.; Zhang, D. Experimental study on diesel engine performance of tractor under transient conditions. Therm. Sci. Eng. Progress 2025, 61, 103509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Heng, Y.; Zheng, K.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, J.; Xia, J. Evaluation of the Performance of a Combined Tillage Implement with Plough and Rotary Tiller by Experiment and DEM Simulation. Processes 2021, 9, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kichler, C.M.; Fulton, J.P.; Raper, R.L.; McDonald, T.P.; Zech, W.C. Effects of transmission gear selection on tractor performance and fuel costs during deep tillage operations. Soil Tillage Res. 2011, 113, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafaei, S.M.; Loghavi, M.; Kamgar, S. Fundamental realization of longitudinal slip efficiency of tractor wheels in a tillage practice. Soil Tillage Res. 2021, 205, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagar, H.; Machavaram, R.; Kulkarni, P.; Soni, P. AI-based engine performance prediction cum advisory system to maximise fuel efficiency and field performance of the tractor for optimum tillage. Syst. Sci. Control Eng. 2024, 12, 2347936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sager, S.M.; Almady, S.S.; Marey, S.A.; Al-Hamed, S.A.; Aboukarima, A.M. Prediction of Specific Fuel Consumption of a Tractor during the Tillage Process Using an Artificial Neural Network Method. Agronomy 2024, 14, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.; Yang, Z.; Mowafy, S.; Zheng, B.; Song, Z.; Luo, Z.; Guo, W. Load characteristics analysis of tractor drivetrain under field plowing operation considering tire-soil interaction. Soil Tillage Res. 2023, 227, 105620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, G.; Zhang, J.; Yan, X.; Dong, C.; Liu, M.; Xu, L. Research on energy-saving control of agricultural hybrid tractors integrating working condition prediction. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e299658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Wang, D.; Cai, Y.; Lai, L. Energy Saving Performance of Agricultural Tractor Equipped with Mechanic-Electronic-Hydraulic Powertrain System. Agriculture 2022, 12, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janulevicius, A.; Damanauskas, V. Validation of relationships between tractor performance indicators, engine control unit data and field dimensions during tillage. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 191, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, H.; Baek, S.; Baek, S.; Choi, J.; Kim, Y.; Kim, W.; Kim, Y. Efficiency Analysis of Powertrain for Internal Combustion Engine and Hydrogen Fuel Cell Tractor According to Agricultural Operations. Sensors 2024, 24, 5494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozer, S.; Haciyusufoglu, F.; Vural, E. Experimental investigation of the effect of the use of nanoparticle additional biodiesel on fuel consumption and exhaust emissions in tractor using a coated engine. Therm. Sci. 2023, 27, 3189–3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, D.; Pachamuthu, S.; Nurun Nabi, M.; Hustad, J.E.; Løvås, T. Theoretical and experimental investigation of diesel engine performance, combustion and emissions analysis fuelled with the blends of ethanol, diesel and jatropha methyl ester. Energy Convers. Manag. 2012, 53, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebedevas, S.; Pukalskas, S.; Žaglinskis, J.; Matijošius, J. Comparative investigations into energetic and ecological parameters of camelina-based biofuel used in the 1Z diesel engine. Transport 2012, 27, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakopoulos, D.C.; Rakopoulos, C.D.; Kakaras, E.C.; Giakoumis, E.G. Effects of ethanol–diesel fuel blends on the performance and exhaust emissions of heavy duty DI diesel engine. Energy Convers. Manag. 2008, 49, 3155–3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siedlecki, M.; Szymlet, N.; Fuc, P.; Kurc, B. Analysis of the Possibilities of Reduction of Exhaust Emissions from a Farm Tractor by Retrofitting Exhaust Aftertreatment. Energies 2022, 15, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rymaniak, L.; Merkisz, J.; Szymlet, N.; Kaminska, M.; Weymann, S. Use of emission indicators related to CO2 emissions in the ecological assessment of an agricultural tractor. Eksploat. Niezawodn. 2021, 23, 605–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniela, L.; Marco, F.; Gunnar, L. Fuel consumption and exhaust emissions during on-field tractor activity: A possible improving strategy for the environmental load of agricultural mechanisation. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 151, 238–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, F.E.; Porte, P.; Slima Ík, D.A.; Upera, J.Í.; Fajman, M. Observation of load transfer from fully mounted plough to tractor wheels by analysis of three point hitch forces during ploughing. Soil Tillage Res. 2017, 172, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahya, A.; Zohadie, M.; Kheiralla, A.F.; Giew, S.K.; Boon, N.E. Mapping system for tractor-implement performance. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2009, 69, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, M.A.A.; Baek, S.; Baek, S.; Kim, W.; Kim, Y.; Kim, Y.; Lee, D.; Lee, K.; Hwang, J. Simulation of Fuel Consumption Based on Engine Load Level of a 95 kW Partial Power-Shift Transmission Tractor. Agriculture 2021, 11, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohrer, R.A.; Pitla, S.; Luck, J.D. Tractor CAN bus interface tools and application development for real-time data analysis. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 163, 104847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, S.; Andersson, I. Self-optimising control of an SI-engine using a torque sensor. Control Eng. Pract. 2008, 16, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Curb weight (kg) | 4155 |

| Tractor size/(mm) | 4530 × 2050 × 2810 |

| Tire size (front/rear) | 11.2–24/16.9–34 |

| Gear (forward + backward) | 16 + 8 |

| Driving form | four-wheel |

| Implement attachment method | three-point suspension |

| Type of plow | five-share plow |

| Width of a plow body (mm) | 200 |

| Matching power (kW) | >50 |

| Tool quality (kg) | 170 |

| Tillage depth (mm) | 200–300 |

| Power | diesel engine |

| Fuel type | 0# diesel |

| Rated power (kW) | 100 |

| Indicated thermal efficiency (%) | 45.85 |

| Barke effective thermal efficiency (%) | 42.95 |

| Parameter | SPN | PGN | Data Domain Location | Scale Factor | Unit | Refresh Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engine speed | 190 | 61444 | Byte 4–5 | 0.125 | RPM | 20 ms |

| Engine output torque | 513 | 61444 | Byte 2–3 | 0.125 | % | −125–125% |

| Fuel flow | 183 | 65253 | Byte 3–4 | 0.05 | L/h | 1 s |

| Gearbox gear | 523 | 65253 | Byte 1 | 1 | - | 50 ms |

| Equipment Name | Type | Precision |

|---|---|---|

| Tension sensor | NOS-C902 | 0–50 k N/0.5% FS |

| GPS | Speedbox-RTK | 0.05 km/h |

| Engine speed senor | FY0802 | ±0.1% FS |

| CAN bus analyzer | Kvaser | Baud rate 40–1000 kbps |

| Property | Specification | Test Method |

|---|---|---|

| Cetane Number | 51 | ATSM D613 |

| Sulfur Content (mg/kg) | 10 | ASTM D4294 |

| Density at 20 °C (kg/m3) | 820–845 | ATSM D4052 |

| Lubricity (μm) | 460 | ASTM D6079 |

| NO | Transmission Gear (-) | Target Velocity (km/h) | Depth of Cultivated Land (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Test 1 | High, turtle, gear III | 5.7 | 23 |

| Test 2 | Low, rabbit, gear I | 7.1 | 23 |

| Test 3 | Low, rabbit, gear II | 8.9 | 23 |

| Test 4 | High, turtle, gear III | 5.7 | 20 |

| Test 5 | High, turtle, gear III | 5.7 | 23 |

| Test 6 | High, turtle, gear III | 5.7 | 26 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, J.; Hu, J.; Chen, S.; Zhang, D.; Sun, C.; Tang, Q. Energy Consumption Assessment of a Tractor Pulling a Five-Share Plow During the Tillage Process. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2619. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242619

Wu J, Hu J, Chen S, Zhang D, Sun C, Tang Q. Energy Consumption Assessment of a Tractor Pulling a Five-Share Plow During the Tillage Process. Agriculture. 2025; 15(24):2619. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242619

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Jiapeng, Juncheng Hu, Siyuan Chen, Daqing Zhang, Chaoran Sun, and Qijun Tang. 2025. "Energy Consumption Assessment of a Tractor Pulling a Five-Share Plow During the Tillage Process" Agriculture 15, no. 24: 2619. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242619

APA StyleWu, J., Hu, J., Chen, S., Zhang, D., Sun, C., & Tang, Q. (2025). Energy Consumption Assessment of a Tractor Pulling a Five-Share Plow During the Tillage Process. Agriculture, 15(24), 2619. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242619