Tracking Heavy Metals and Resistance-Related Genes in Agricultural Karst Soils Derived from Various Parent Materials

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

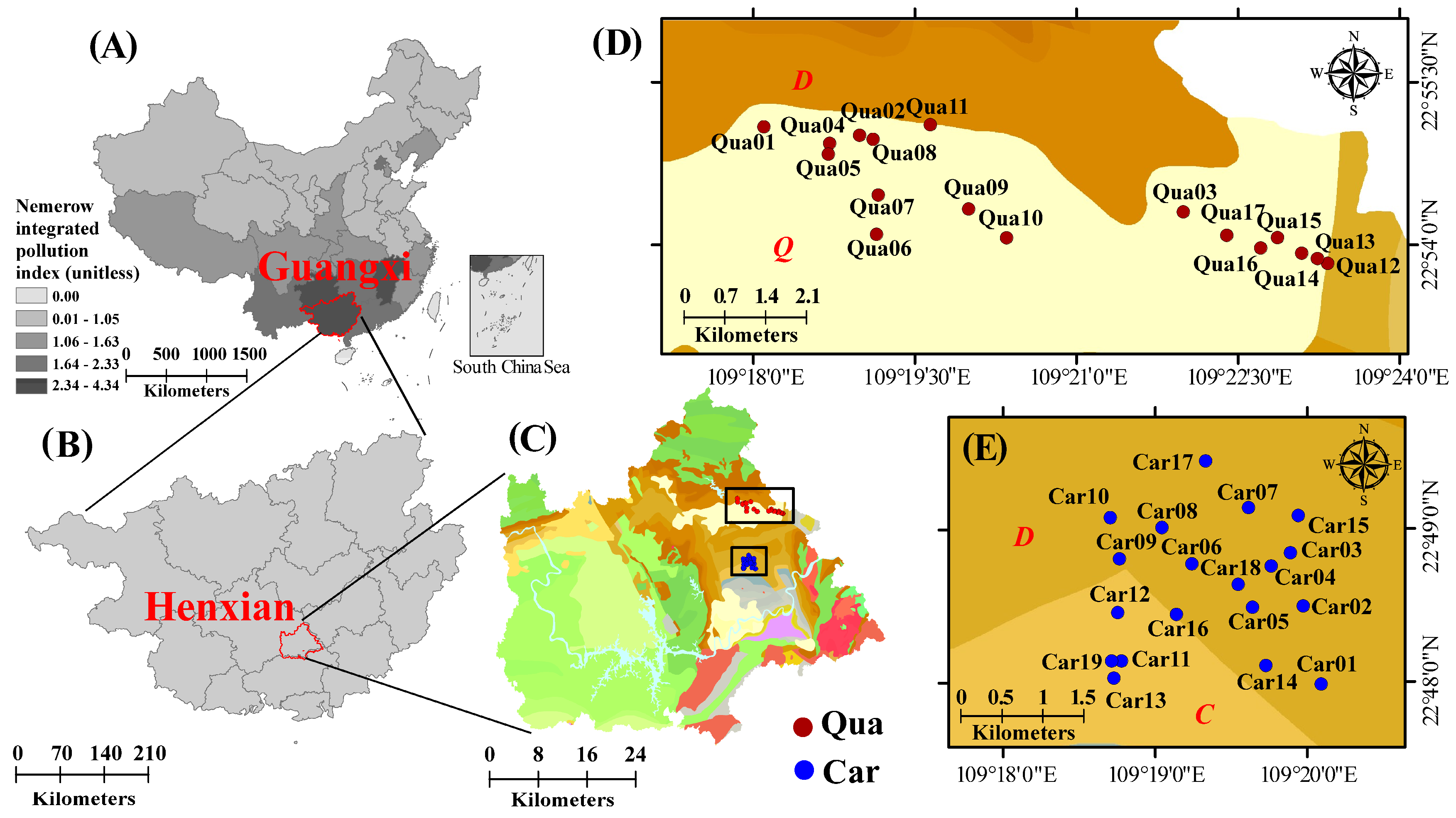

2.1. Soil Sample Collection and Biogeochemical Analysis

2.2. Metagenomic Sequencing Analysis and Taxonomic Annotation

2.3. Annotation of Resistance-Related Genes

2.4. Analysis of Co-Associated Networks

2.5. Statistical Methods

3. Results

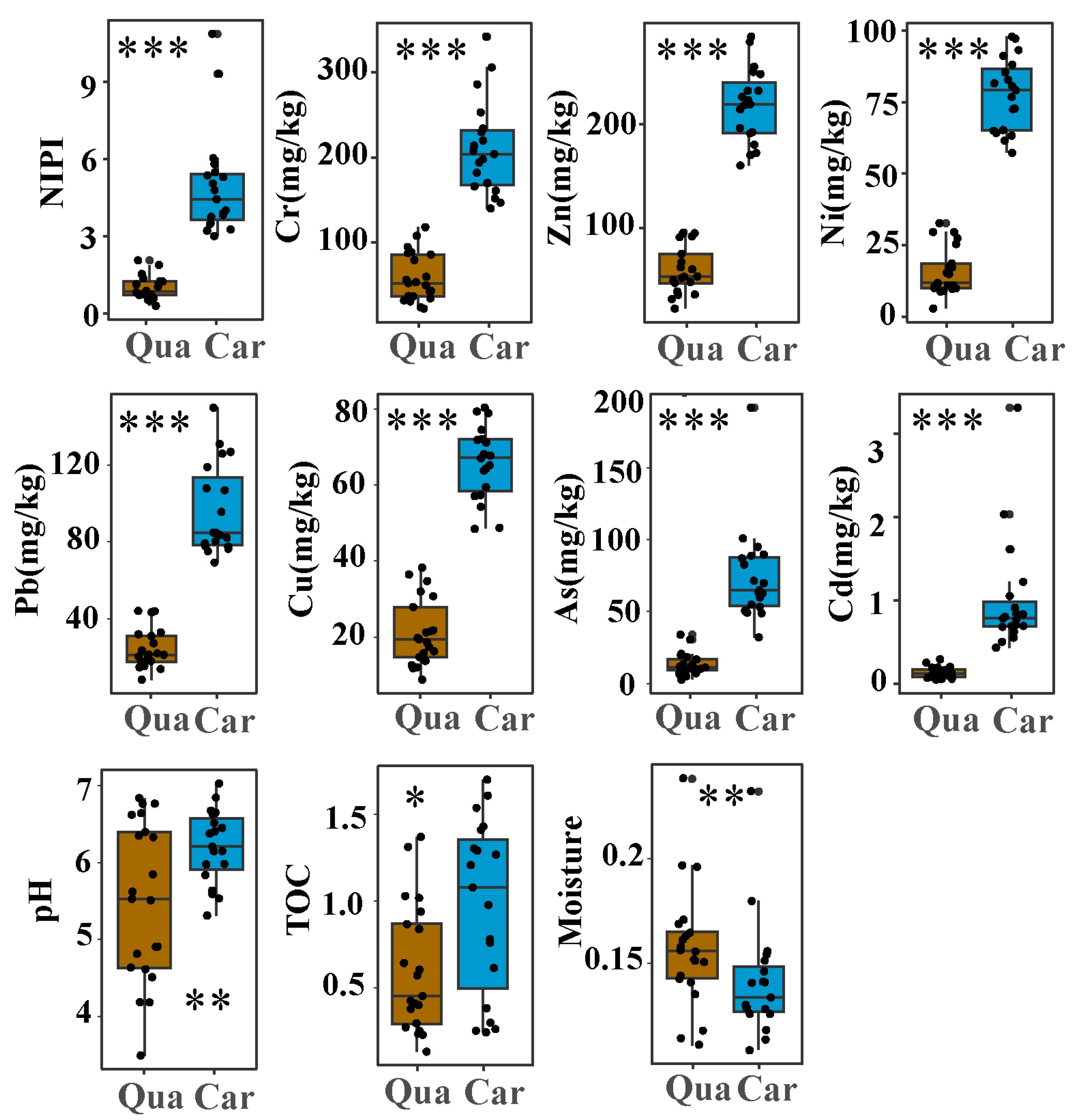

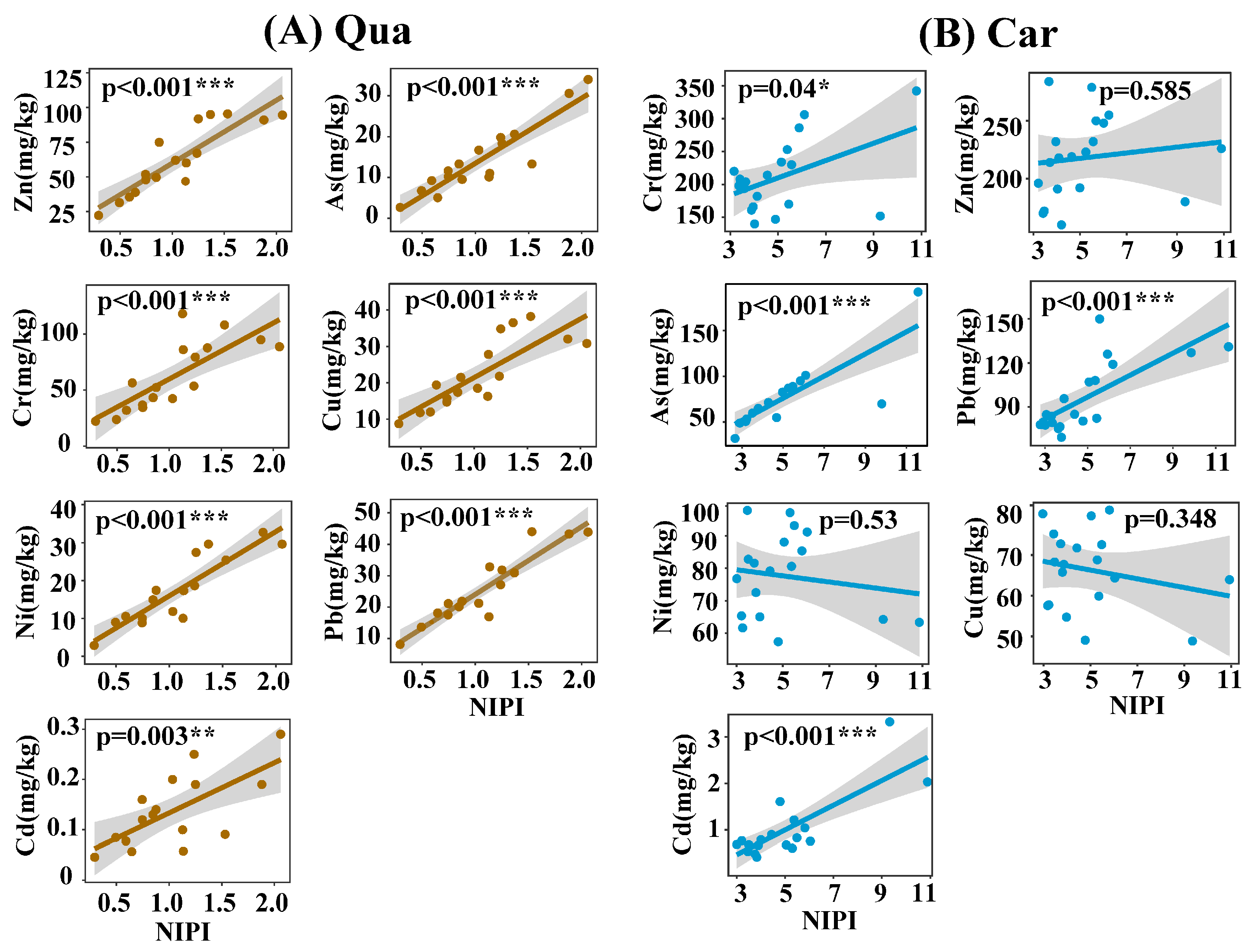

3.1. Biogeochemical Properties and Heavy Metals in Soil Samples

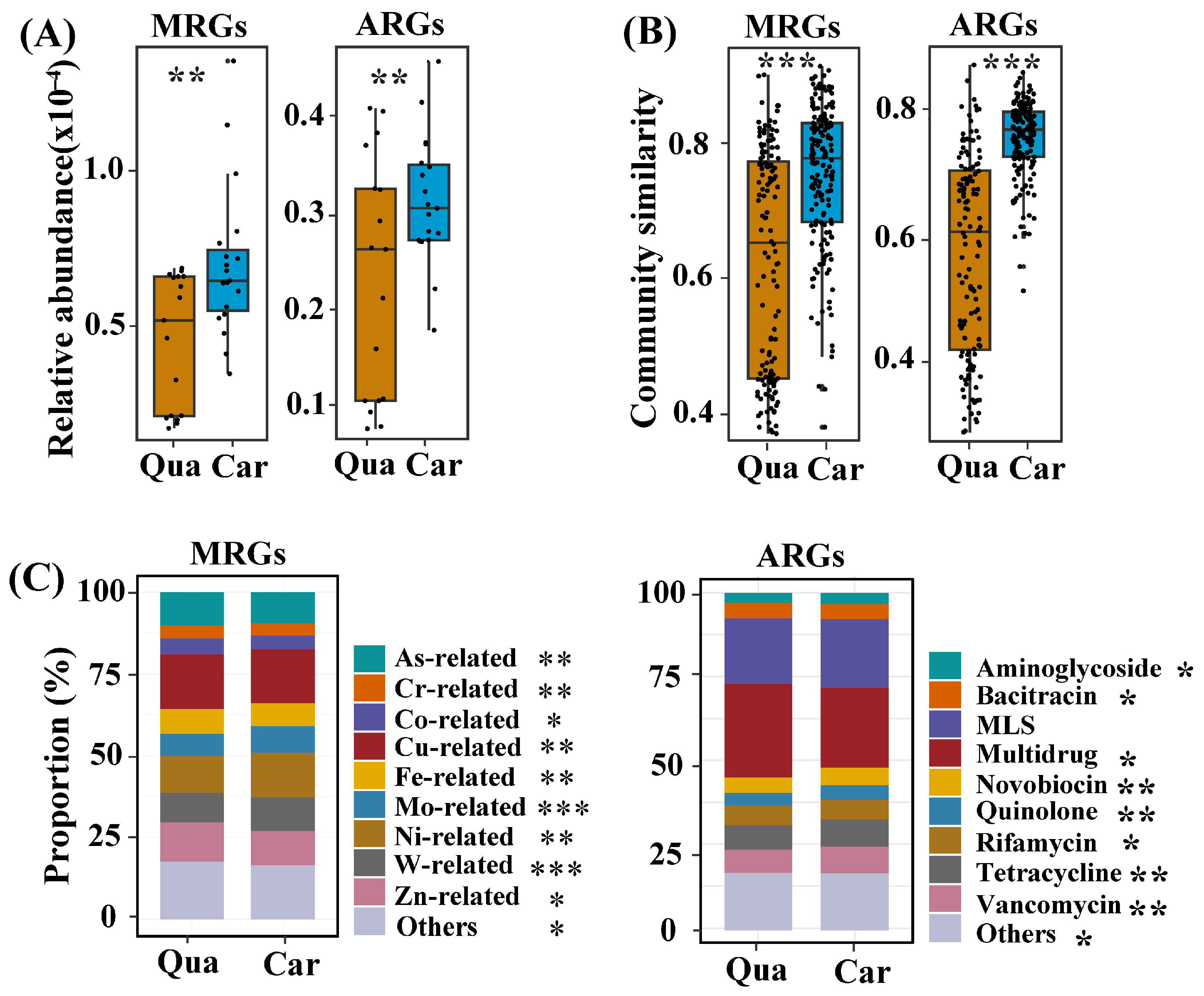

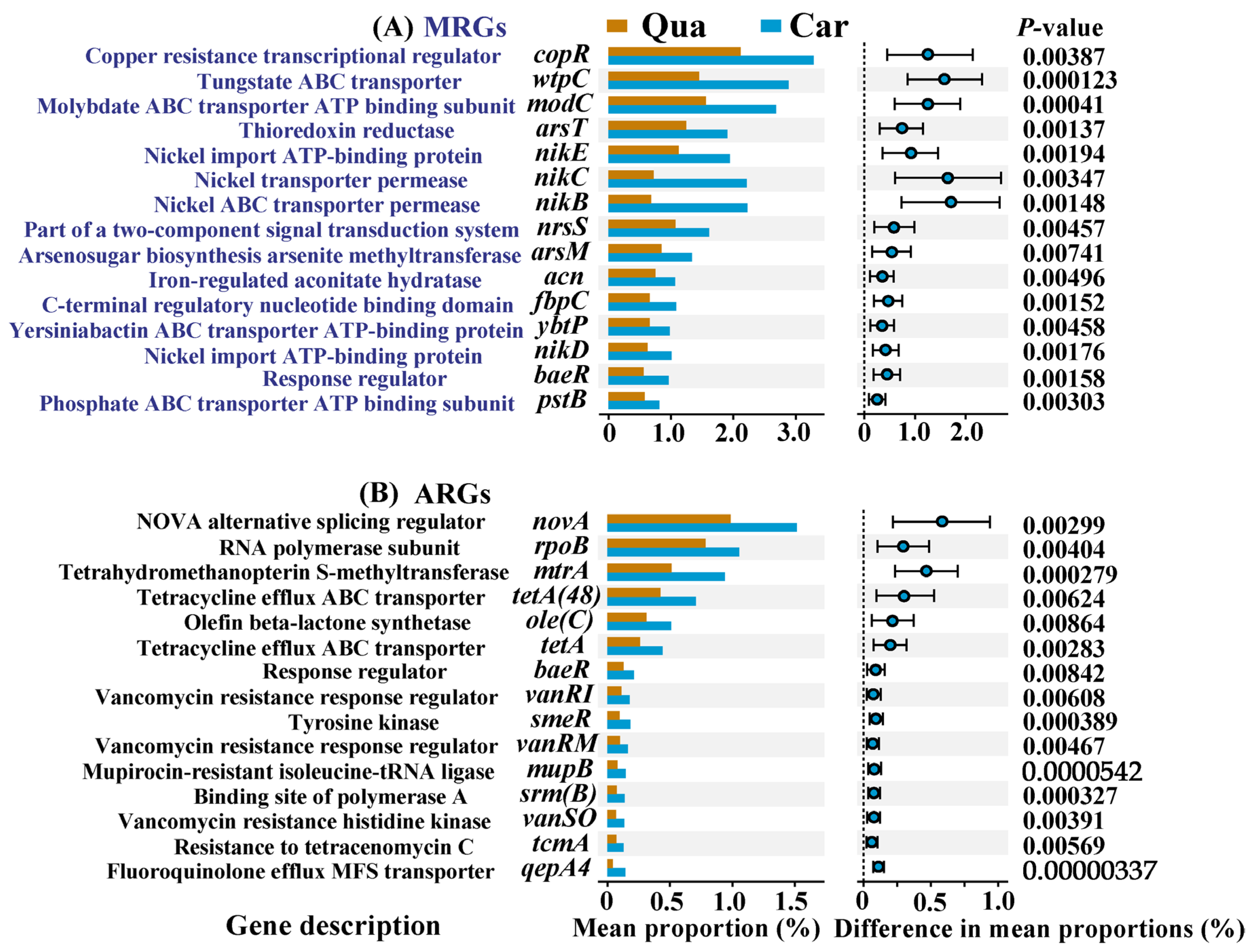

3.2. Profiles of Resistance-Related Genes in Soil Samples

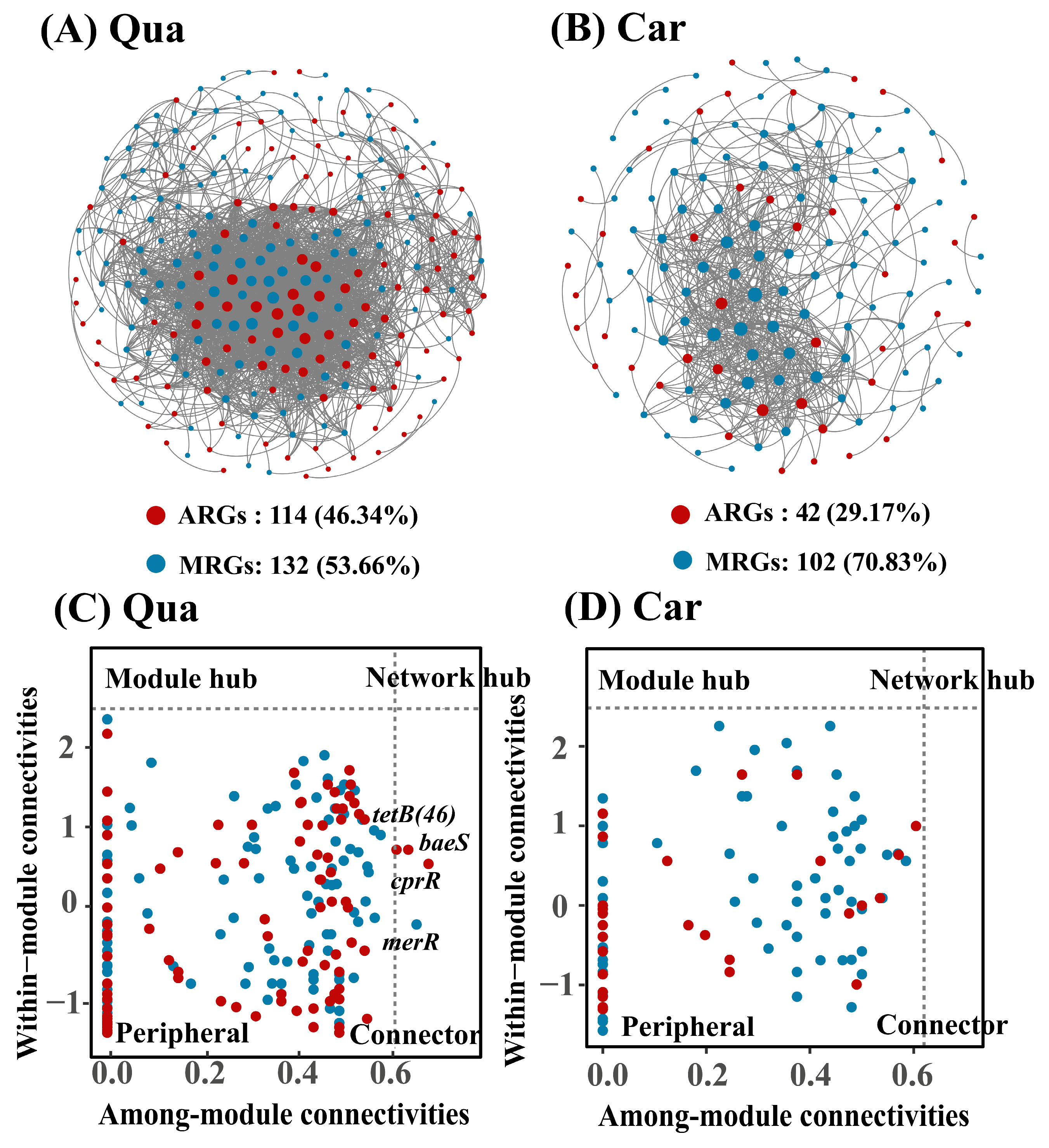

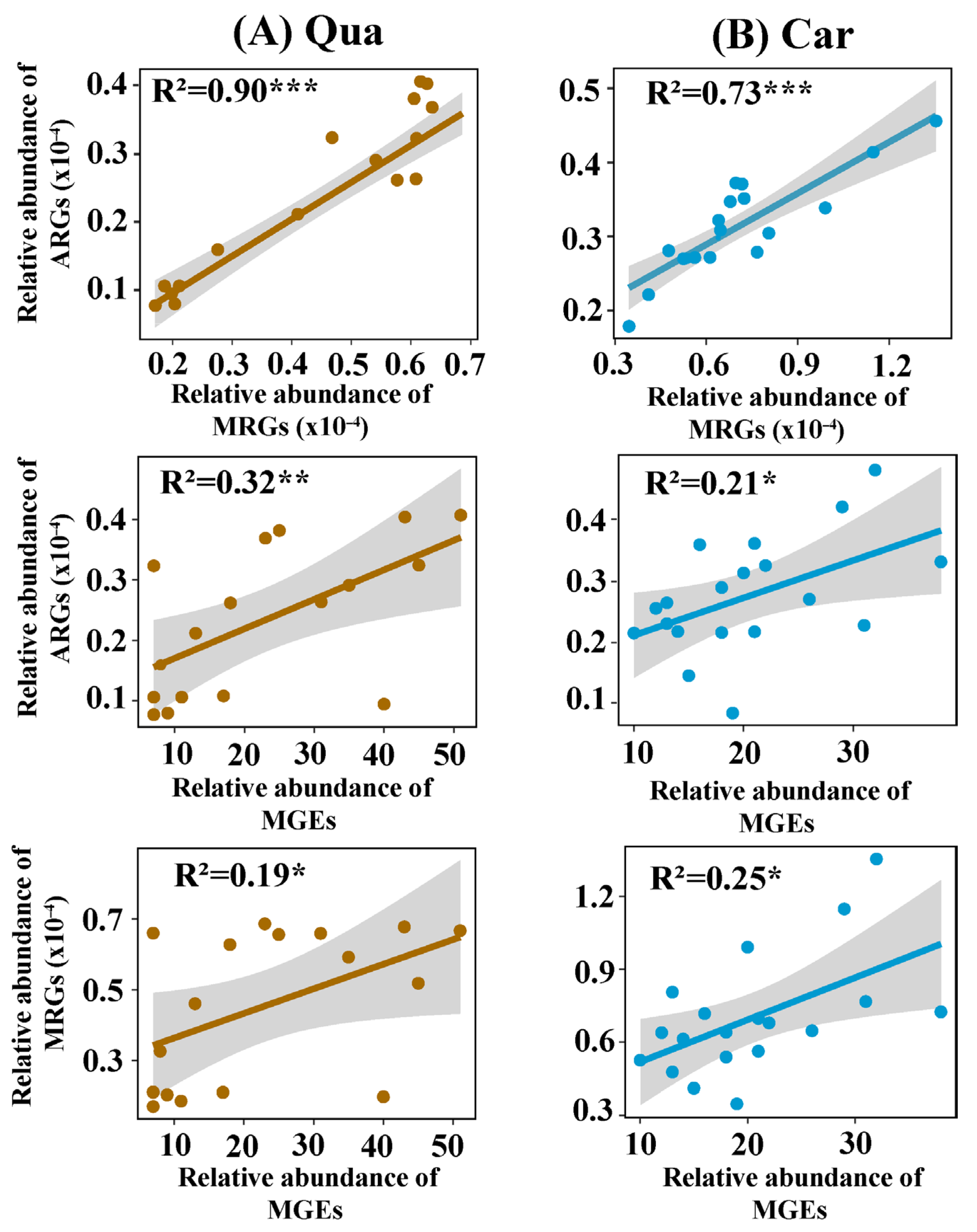

3.3. Interactions Among Heavy Metals, MRGs, and ARGs in Karst Soil Samples

4. Discussion

4.1. Geological Factors Significantly Influenced the Patterns of Heavy Metals and Resistance-Related Genes in Karst Soils

4.2. Microbial Activity Had a Different Influence on the Interactions of HMs and Resistance-Related Genes in Karst Soils

4.3. Significance for the Assessment of Ecological Risks of HM Contamination in Karst Soils

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, Y.; Hu, H.W.; Su, J.Q.; Hao, X.; Guo, H.; Liu, Y.R.; Zhu, Y.G. Influence of legacy mercury on antibiotic resistomes: Evidence from agricultural soils with different cropping systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 13913–13922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Chen, W.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Wen, Y.; Bostick, B.C.; Wen, Y.; He, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhuo, X.; et al. New strategy for exploring the accumulation of heavy metals in soils derived from different parent materials in the karst region of southwestern China. Geoderma 2022, 417, 115806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, D.; Jia, X.; Wang, L.; McGrath, S.P.; Zhu, Y.-G.; Hu, Q.; Zhao, F.-J.; Bank, M.S.; O’Connor, D.; Nriagu, J. Global soil pollution by toxic metals threatens agriculture and human health. Science 2025, 388, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coban, O.; De Deyn, G.B.; van der Ploeg, M. Soil microbiota as game-changers in restoration of degraded lands. Science 2022, 375, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, G.; Hermann, T.; Szatmári, G.; Pásztor, L. Maps of heavy metals in the soils of the European Union and proposed priority areas for detailed assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 565, 1054–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, M.; Akhbarizadeh, R.; Haghighifard, N.J.; Barzegar, G.; Jorfi, S. Geochemical determination and pollution assessment of heavy metals in agricultural soils of south western of Iran. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 2019, 17, 657–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadd, G.M. Metals, minerals and microbes: Geomicrobiology and bioremediation. Microbiology 2010, 156, 609–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, W.B. Karst hydrology: Recent developments and open questions. Eng. Geol. 2002, 65, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Liang, J.-L.; Su, J.-Q.; Jia, P.; Lu, J.-l.; Zheng, J.; Wang, Z.; Feng, S.-w.; Luo, Z.-h.; Ai, H.-x.; et al. Globally distributed mining-impacted environments are underexplored hotspots of multidrug resistance genes. ISME J. 2022, 16, 2099–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Zhong, Z.; Li, X.; Cao, Z.; Zheng, X.; Feng, G. Characterization of heavy metal, antibiotic pollution, and their resistance genes in paddy with secondary municipal-treated wastewater irrigation. Water Res. 2024, 252, 121208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alloway, B.J. Heavy Metals in Soils: Trace Metals and Metalloids in Soils and their Bioavailability; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, P.; Zhang, W.; Nottingham, A.T.; Xiao, D.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Xu, L.; Chen, H.; Xiao, J.; Duan, P.; Tang, T.; et al. Lithological controls on soil aggregates and minerals regulate microbial carbon use efficiency and necromass stability. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 21186–21199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Shaheen, S.M.; Swertz, A.-C.; Liu, C.; Anderson, C.W.N.; Fendorf, S.; Wang, S.-L.; Feng, X.; Rinklebe, J. First Insight into the Mobilization and Sequestration of Arsenic in a Karstic Soil during Redox Changes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 17850–17861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.G.; Zhao, Y.; Li, B.; Huang, C.L.; Zhang, S.Y.; Yu, S.; Chen, Y.S.; Zhang, T.; Gillings, M.R.; Su, J.Q. Continental-scale pollution of estuaries with antibiotic resistance genes. Nat. Microbiol. 2017, 2, 16270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Huang, Q.; Peng, X.; Zhou, X.; Gao, S.; Li, Y.; Luo, X.; Zhao, Y.; Rensing, C.; Su, J.; et al. MRG chip: A high-throughput qpcr-based tool for assessment of the heavy metal(loid) resistome. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 10656–10667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, S.; Feng, J.; Bi, L.; Hu, H.W.; Hao, X.; Huang, Q.; Liu, Y.R. Tracking soil resistance and virulence genes in rice-crayfish co-culture systems across China. Environ. Int. 2023, 172, 107789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.R.; van der Heijden, M.G.A.; Riedo, J.; Sanz-Lazaro, C.; Eldridge, D.J.; Bastida, F.; Moreno-Jimenez, E.; Zhou, X.Q.; Hu, H.W.; He, J.Z.; et al. Soil contamination in nearby natural areas mirrors that in urban greenspaces worldwide. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.W.; Wang, J.T.; Li, J.; Shi, X.Z.; Ma, Y.B.; Chen, D.; He, J.Z. Long-term nickel contamination increases the occurrence of antibiotic resistance genes in agricultural soils. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 790–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Guo, X.; Lin, J.; Wang, X.; He, D.; Zeng, R.; Meng, J.; Luo, J.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Moreno-Jiménez, E.; et al. Metallic micronutrients are associated with the structure and function of the soil microbiome. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, R.; Xue, N.; Wang, S.; Zhou, X.; Zhao, L.; Song, W.; Yang, Y. Heavy metal(loid)s shape the soil bacterial community and functional genes of desert grassland in a gold mining area in the semi-arid region. Environ. Res. 2022, 214, 113749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Liu, W.; Xu, H.; Cui, X.; Li, J.; Chen, J.; Zheng, B. Characterizations of heavy metal contamination, microbial community, and resistance genes in a tailing of the largest copper mine in China. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 280, 116947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Cheng, S.; Fang, H.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Shi, F.; Zhou, Y. Copper and cadmium co-contamination affects soil bacterial taxonomic and functional attributes in paddy soils. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 329, 121724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Fang, H.; Wang, C.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Mai, B.; He, Z.; Wu, R.; Li, K. The assembly, biogeography and co-occurrence of abundant and rare microbial communities in a karst river. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1228813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Wang, S.; Xu, X.; Huang, L.; Gu, Q.; Liu, H. Spatial distribution and risk assessment of heavy metal pollution from enterprises in China. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 480, 136147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhao, J.; Liu, Y.; Huang, S.; Zhao, C.; Jiang, Z.; Gu, Y.; Xiao, J.; Wu, Y.; Ying, R.; et al. Deciphering soil resistance and virulence gene risks in conventional and organic farming systems. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 468, 133788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.Y.; Lie, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhu, Y.G.; Penuelas, J.; Neilson, R.; Su, X.; Liu, Z.; Chu, G.; Meng, Z.; et al. Distinct patterns of soil bacterial and fungal community assemblages in subtropical forest ecosystems under warming. Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 29, 1501–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Hu, F.; Wang, F.; Xu, M.; Jia, Z.; Amelung, W.; Mei, Z.; Han, X.; Virta, M.; Jiang, X.; et al. Distinct assembly patterns of soil antibiotic resistome revealed by land-use changes over 30 years. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 10216–10226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, J.; Xie, W.-Y.; Wang, P. Metagenomic insights into the ecological risks of multiple heavy metals on soil bacterial communities and resistance-related genes. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 303, 119048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Y.; Chen, L.; Ding, P.; Liu, L.; He, Q.; Chen, B.; Duan, Y. Different exposure profile of heavy metal and health risk between residents near a Pb-Zn mine and a Mn mine in Huayuan county, South China. Chemosphere 2019, 216, 352–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Yang, Y.; Ma, L.; Ju, F.; Guo, F.; Tiedje, J.M.; Zhang, T. Metagenomic and network analysis reveal wide distribution and co-occurrence of environmental antibiotic resistance genes. ISME J. 2015, 9, 2490–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Zhao, Z.; Zhu, D.; Pan, X.; Yang, Y. Rare resistome rather than core resistome exhibited higher diversity and risk along the Yangtze River. Water Res. 2024, 249, 120911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Salzberg, S.L. Ultrafast and accurate 16S rRNA microbial community analysis using Kraken 2. Microbiome 2020, 8, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Xie, W.-Y.; Liu, H.-J.; Chen, C.; Chen, S.-Y.; Jiang, G.-F.; Zhao, F.-J. Assessing intracellular and extracellular distribution of antibiotic resistance genes in the commercial organic fertilizers. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 929, 172558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Xu, L.; Montoya, L.; Madera, M.; Hollingsworth, J.; Chen, L.; Purdom, E.; Singan, V.; Vogel, J.; Hutmacher, R.B.; et al. Co-occurrence networks reveal more complexity than community composition in resistance and resilience of microbial communities. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, T.; Xie, P.; Yang, S.; Niu, G.; Liu, X.; Ding, Z.; Xue, C.; Liu, Y.X.; Shen, Q.; Yuan, J. ggClusterNet: An R package for microbiome network analysis and modularity-based multiple network layouts. iMeta 2022, 1, e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Wen, Y.; Peng, Z.; Xu, D.; Xiao, J. Divergent risk gene profiles in smallholder and large-scale paddy farms. Environ. Res. 2025, 285, 122406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Xiao, J.; Ji, J.; Liu, Y. Arsenate Adsorption on Different Fractions of Iron Oxides in the Paddy Soil from the Karst Region of China. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2021, 106, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wen, Y.; Zhai, H.; Yuan, Y.; Guo, C.; Wang, L.; Wu, F.; Liu, C.; Xiao, J.; et al. A kinetics-coupled multi-surface complexation model deciphering arsenic adsorption and mobility across soil types. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 948, 174856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.; Li, B.; Guan, D.-X.; Wu, Z.; Li, X.; Ji, W.; Liu, W.; Yu, T.; Yang, Z. Enrichment Mechanisms of Cadmium in Natural Manganese-Rich Nodules from Karst Soils. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 7256–7267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Tang, Z.; Tian, W.; Xi, Y.; Zhang, J. Long-term fertilization lowers the alkaline phosphatase activity by impacting the phoD-harboring bacterial community in rice-winter wheat rotation system. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 821, 153406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Guo, S.; Li, K.; Xu, P.; Ok, Y.S.; Jones, D.L.; Zou, J. Antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in agricultural soils: A systematic analysis. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 53, 847–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.P.J.; Wucher, B.R.; Nadell, C.D.; Foster, K.R. Bacterial defences: Mechanisms, evolution and antimicrobial resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 519–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Liu, Y.; Cao, W.; Zhang, L.; Xu, F.; Liu, J.; Wen, Y.; Xiao, J.; Wang, L.; Zhuo, X.; et al. A process-based model for describing redox kinetics of Cr(VI) in natural sediments containing variable reactive Fe(II) species. Water Res. 2022, 225, 119126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhao, M.; Cai, B.; Song, X.; Tang, R.; Huang, X.; Huang, H.; Huang, J.; Fan, Z. Risk assessment and driving factors of trace metal(loid)s in soils of China. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 309, 119772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Wu, F.; Zhang, J.; Ai, S.; Liu, Z. Microbial community composition and degradation potential of petroleum-contaminated sites under heavy metal stress. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 457, 131814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, N.; Gu, X.; Wen, Y.; Guo, C.; Ji, J. Geochemical speciation and activation risks of Cd, Ni, and Zn in soils with naturally high background in karst regions of southwestern China. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 486, 137100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Yang, Z.; Filippelli, G.M.; Ji, J.; Ji, W.; Liu, X.; Wang, L.; Yu, T.; Wu, T.; Zhuo, X.; et al. Distribution and secondary enrichment of heavy metal elements in karstic soils with high geochemical background in Guangxi, China. Chem. Geol. 2021, 567, 120081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Li, W.; Yang, Z.; Zhuo, X.; Guan, D.-X.; Song, Y.; Guo, C.; Ji, J. Evaluation of various approaches to predict cadmium bioavailability to rice grown in soils with high geochemical background in the karst region, Southwestern China. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 258, 113645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradl, H. Adsorption of heavy metal ions on soils and soil constituents. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2004, 277, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Y.; Li, W.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Ji, J. Enrichment and source identification of Cd and other heavy metals in soils with high geochemical background in the karst region, Southwestern China. Chemosphere 2020, 245, 125620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Shen, J.P.; Zhang, L.M.; Du, S.; Hu, H.W.; He, J.Z. Arsenic and cadmium as predominant factors shaping the distribution patterns of antibiotic resistance genes in polluted paddy soils. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 389, 121838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- China National Environmental Monitoring Centre (CNEMC). Elemental Background Values of Soils in China; Environmental Science Press of China: Beijing, China, 1990. [Google Scholar]

| Heavy Metal | Percentage of Heavy Metal Content in Soil Samples Exceeding the Risk Screening Value (%) a | Percentage of Heavy Metal Content in Soil Samples Exceeding the Risk Intervention Value (%) b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qua | Car | Qua | Car | |

| Cr | 0 | 94.11 | 0 | 0 |

| Zn | 0 | 64.71 | 0 | 0 |

| Ni | 0 | 47.06 | 0 | 0 |

| Pb | 0 | 41.18 | 0 | 0 |

| Cu | 0 | 64.71 | 0 | 0 |

| As | 11.76 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Cd | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiao, J.; Liu, C.; Mei, H.; Gong, C.; Huang, C. Tracking Heavy Metals and Resistance-Related Genes in Agricultural Karst Soils Derived from Various Parent Materials. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2596. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242596

Xiao J, Liu C, Mei H, Gong C, Huang C. Tracking Heavy Metals and Resistance-Related Genes in Agricultural Karst Soils Derived from Various Parent Materials. Agriculture. 2025; 15(24):2596. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242596

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiao, Jian, Chuan Liu, Hanxiang Mei, Changxingzi Gong, and Chichao Huang. 2025. "Tracking Heavy Metals and Resistance-Related Genes in Agricultural Karst Soils Derived from Various Parent Materials" Agriculture 15, no. 24: 2596. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242596

APA StyleXiao, J., Liu, C., Mei, H., Gong, C., & Huang, C. (2025). Tracking Heavy Metals and Resistance-Related Genes in Agricultural Karst Soils Derived from Various Parent Materials. Agriculture, 15(24), 2596. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242596