A Comparative Study of Neural Network Models for China’s Soybean Futures Price Forecasting

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Univariate forecasting: Under a fixed data split, we conduct a unified evaluation of Time-LLM, SOFTS, TiDE, iTransformer, PatchTST, TimesNet (Temporal 2D-Variation Modeling for General Time Series Analysis), TSMixerx, TCN, and TFT (Temporal Fusion Transformer), with the canonical recurrent neural network LSTM serving as the benchmark.

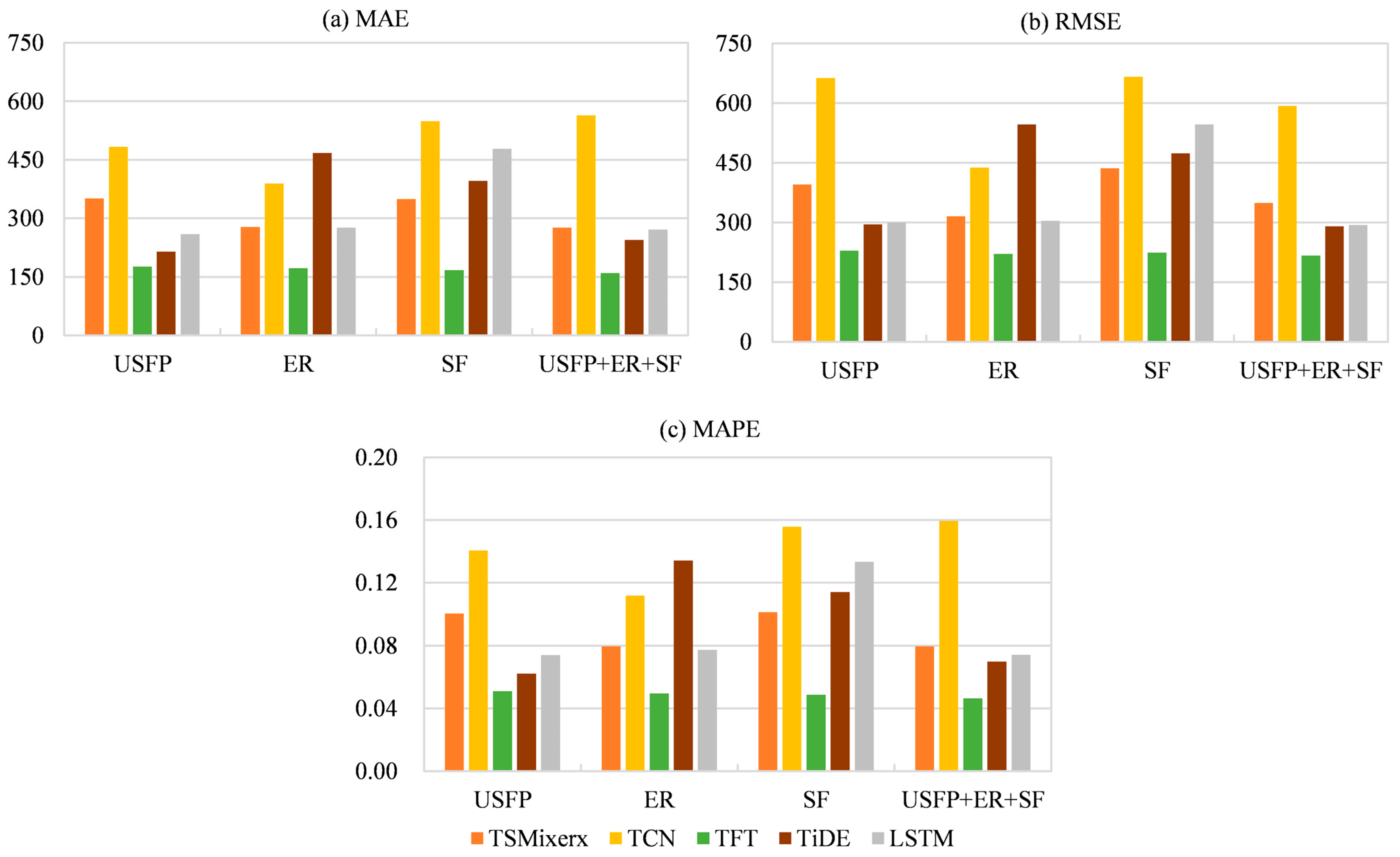

- Single-target multivariate forecasting: We take the DCE No. 2 soybean futures price as the forecasting target. Using models capable of processing exogenous variables (namely TSMixer, TCN, TFT, TiDE, and LSTM), we build multivariate models to test whether incorporating these variables improves predictive performance.

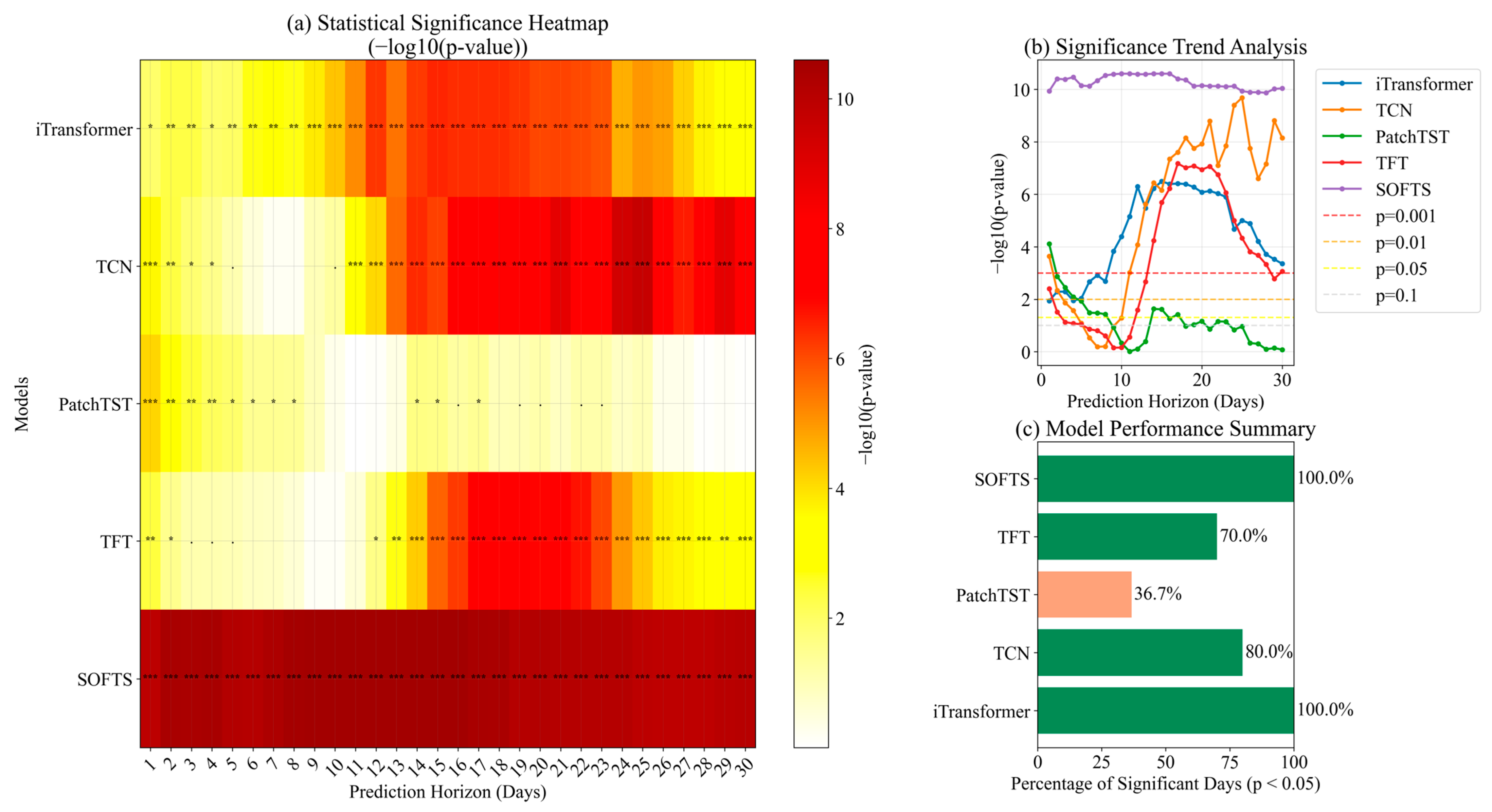

- Multi-step forecasting performance and robustness evaluation: We evaluate all models across varying forecast horizons to examine the robustness of their performance as the horizon changes. This analysis provides practical guidance for model selection across different decision cycles.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset Description

2.2. Data Preprocessing

2.3. Research Methods

2.3.1. MLP-Based Models

- SOFTS

- TiDE

- TSMixer

2.3.2. CNN-Based Models

- TCN

- TimesNet

2.3.3. Transformer-Based Models

- PatchTST

- iTransformer

- TFT

2.3.4. LLM-Based Models

2.4. Experimental Evaluation Metrics

2.5. Hyperparameter Optimization

2.6. Computational Setup

3. Results

3.1. Results: Univariate Forecasting

3.2. Results: Univariate Target with Exogenous Covariates

3.3. Results: Multi-Horizon Performance Comparison

4. Discussion

4.1. Model Performance Discussion

4.2. Exogenous Covariates Discussion

4.3. Model Applications Discussion

4.4. Limitations and Future Work

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

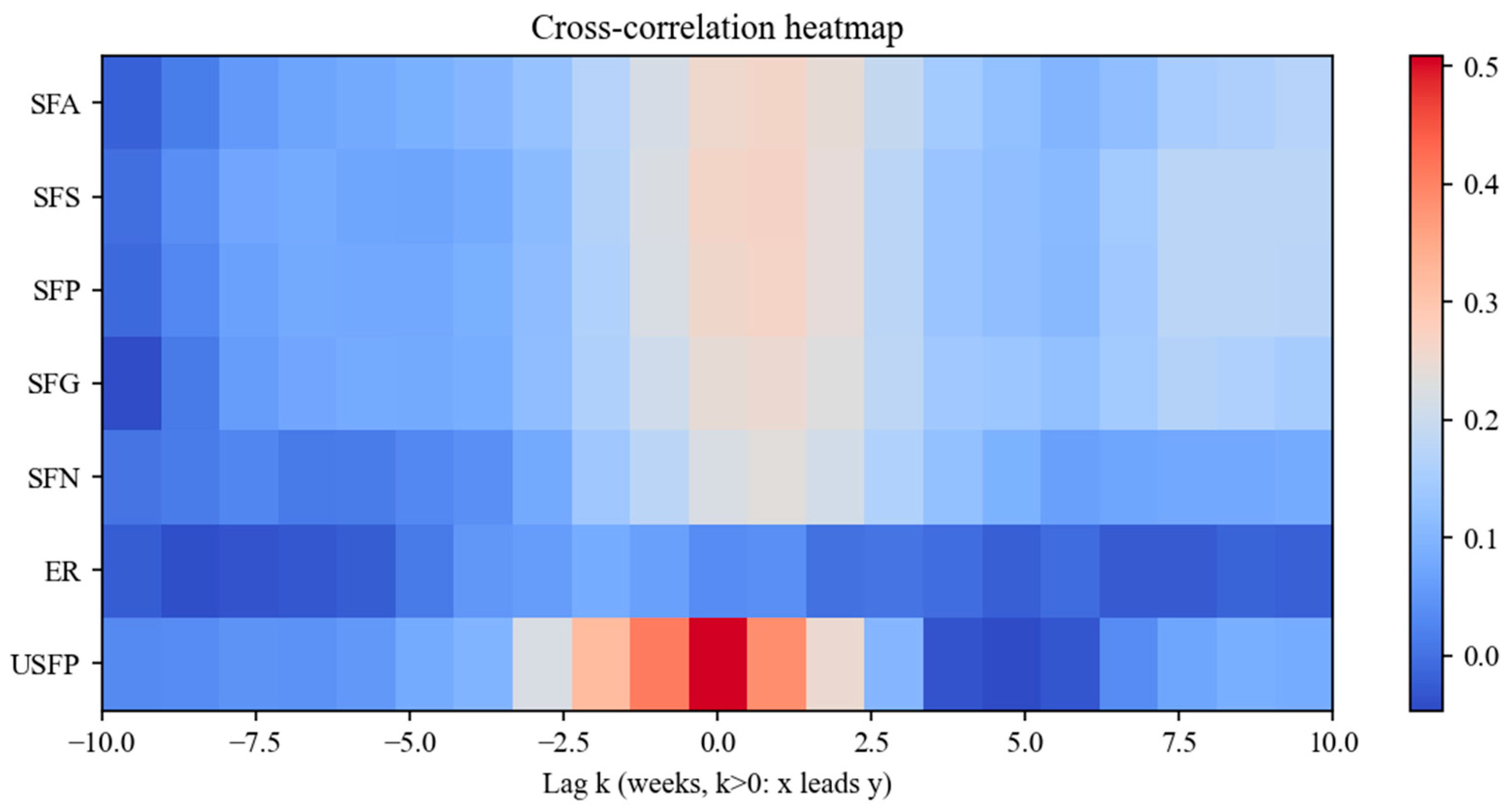

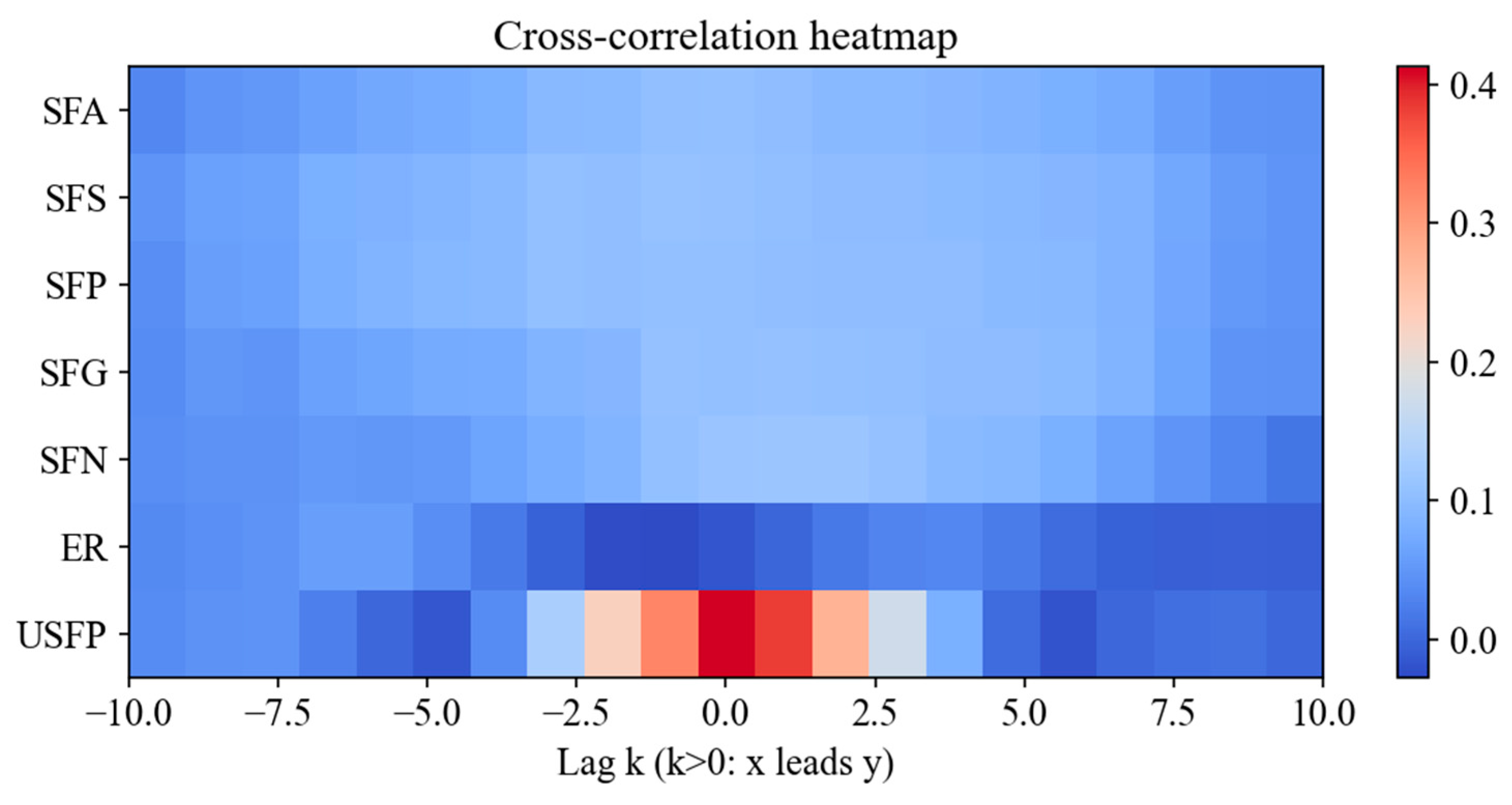

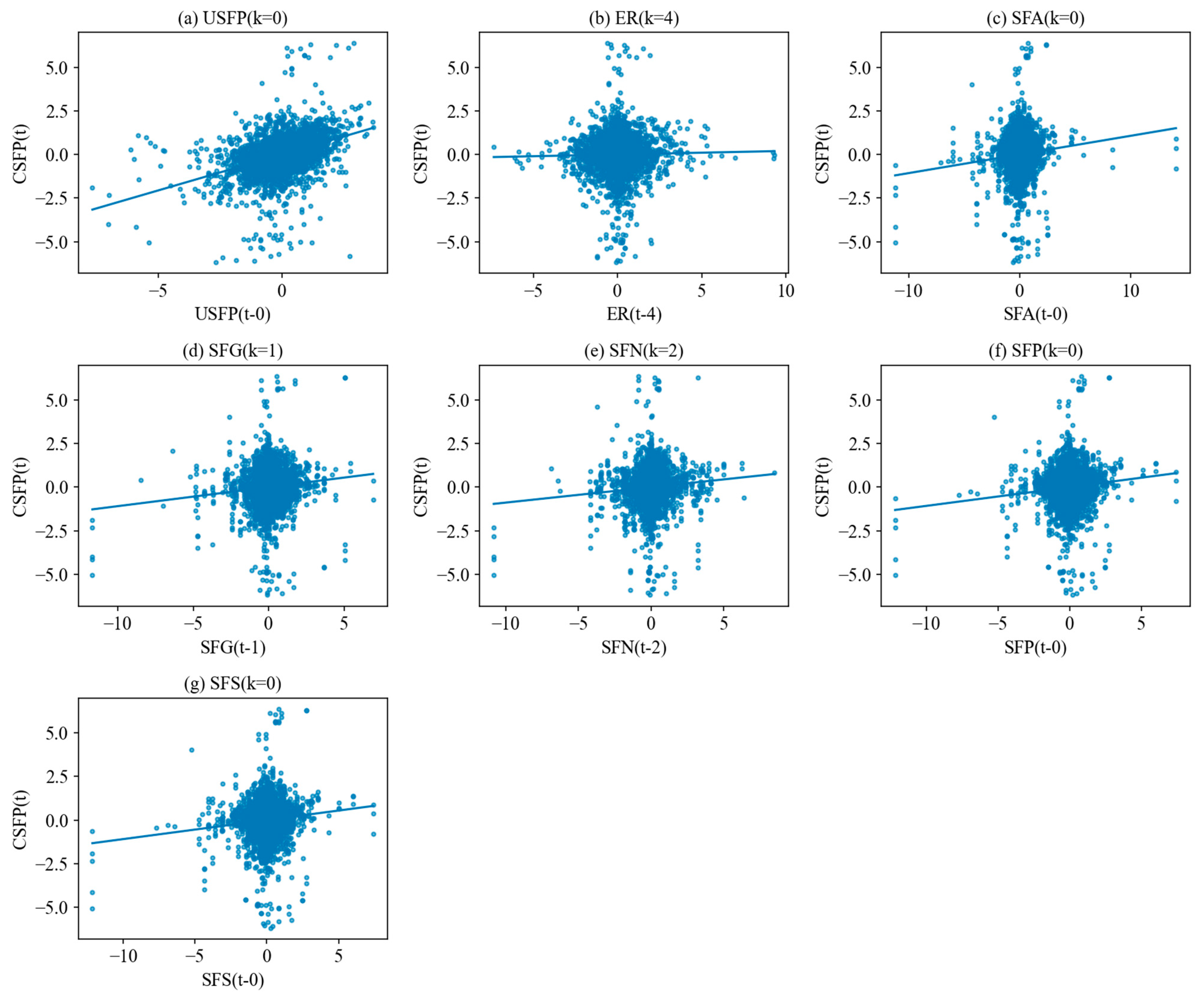

Appendix A.1. Cross-Correlation and Lead–Lag Analysis: Weekly Data

Appendix A.2. Cross-Correlation and Lead–Lag Analysis: Daily Data (Robustness Check)

Appendix B

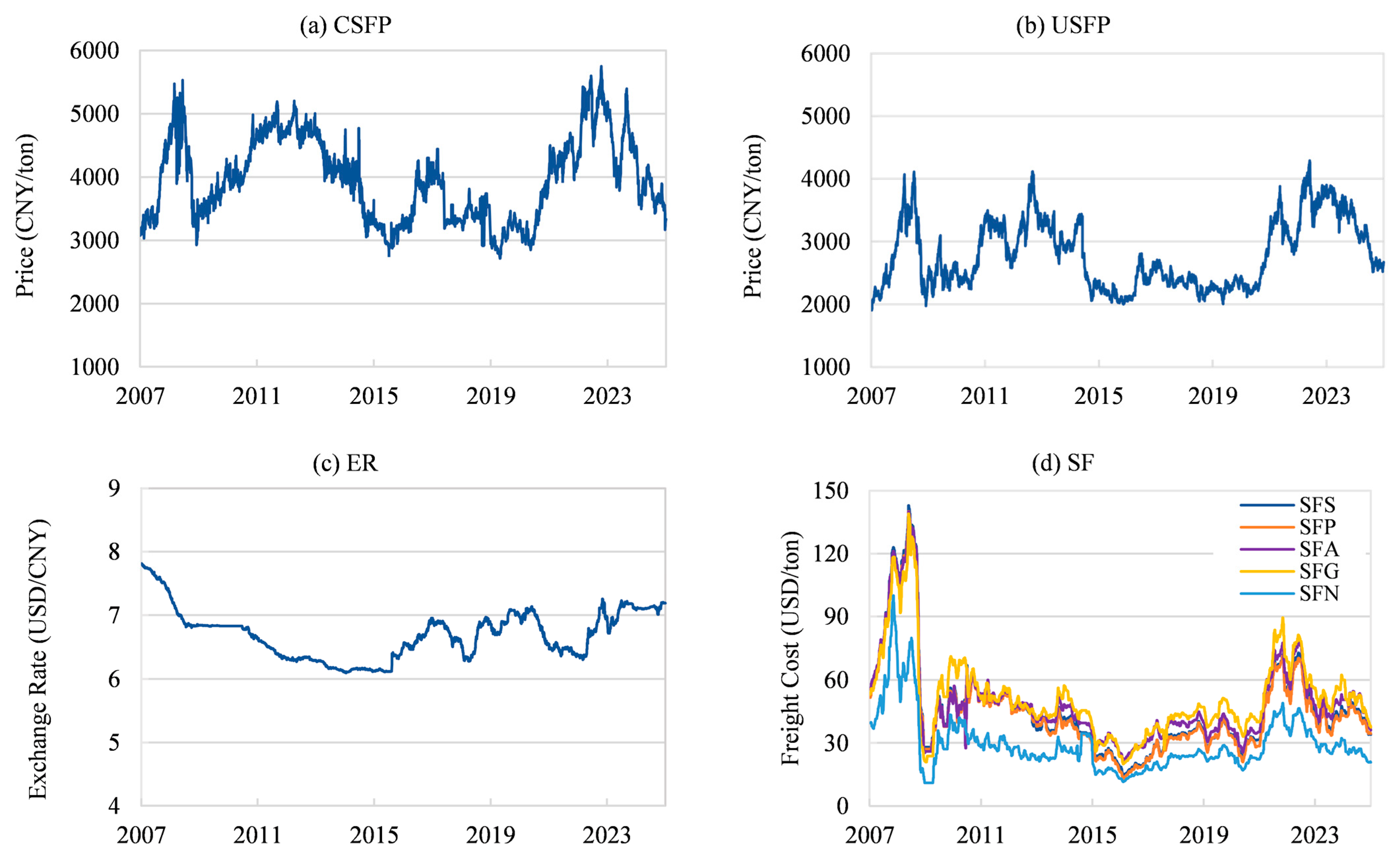

Appendix B.1. Temporal Dynamics of Major Variables

Appendix B.2. Hyperparameter Search Spaces and Model Configurations

| Category | Parameter | Setting/Search Space |

|---|---|---|

| General | learning_rate | 10−5–10−2 (log-uniform) |

| batch_size | {8, 16, 32} | |

| input_size | {365, 730} | |

| max_steps | 1000 | |

| random_seed | 1–10 | |

| iTransformer | d_model | 64 |

| n_heads | 4 | |

| TiDE | hidden_size | 256 |

| decoder_output_dim | {8, 16, 32} | |

| num_encoder_layers/num_decoder_layers | {1, 2, 3} | |

| PatchTST | patch_len | {16, 24} |

| n_heads | {4, 16} | |

| TCN | n_layers | 4 |

| kernel_size | 3 | |

| dilation | Fixed as {1, 2, 4, 8} | |

| TFT | hidden_size | 64 |

| n_heads | 4 | |

| SOFTS/TimesNet/TSMixer | model_dim | {64, 128} |

| LSTM | hidden_size n_layers | 200 {1, 2, 3} |

Appendix C

Appendix C.1. Comprehensive Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test Analysis

Appendix C.2. Robustness Check: Eliminating the Impact of Rollover Jumps

| Model | Price MAPE (Rank) | Return MAE (Rank) | Return RMSE (Rank) |

|---|---|---|---|

| iTransformer | 0.0073 (1) | 0.002295 (5) | 0.002547 (5) |

| TFT | 0.0094 (2) | 0.001921 (2) | 0.002245 (2) |

| TCN | 0.01 (3) | 0.002288 (4) | 0.002423 (3) |

| PatchTST | 0.01 (4) | 0.002558 (6) | 0.002771 (6) |

| TiDE | 0.0229 (5) | 0.00684 (10) | 0.008479 (10) |

| SOFTS | 0.0248 (6) | 0.002187 (3) | 0.002537 (4) |

| TimesNet | 0.028 (7) | 0.001704 (1) | 0.001991 (1) |

| TSMixerx | 0.0435 (8) | 0.002952 (8) | 0.003262 (8) |

| LSTM | 0.0741 (9) | 0.006099 (9) | 0.007707 (9) |

| TimeLLM | 0.0875 (10) | 0.002806 (7) | 0.002877 (7) |

References

- Li, J.L.; Chen, M.; Cui, L. Research on the influence of domestic and foreign soybean futures price on spot price: From the perspective of price linkage. J. Northwest Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2021, 51, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.Y.; Jin, P.L.; Wang, W.T.; Mao, Y.X. Research on import risks and optimization of import source distribution of soybeans in China. China Oils Fats 2025. Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- General Administration of Customs of the People’s Republic of China. Online Query Platform for Customs Statistics. 2025. Available online: http://stats.customs.gov.cn/ (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China. Statistical Communiqué of the People’s Republic of China on the 2024 National Economic and Social Development. 2025. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/zxfb/202502/t20250228_1958817.html (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Xiang, C.L. Study on the Influencing Factors and Forecast of Soybean Prices in China. Ph.D. Thesis, Anhui University of Agriculture, Hefei, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.R.; Zhang, Y.M.; Fan, S.G.; Chen, K.Z.; Wu, Q. The impact of extreme weather events on global soybean markets and China’s imports. J. Agric. Econ. 2025, 76, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.N.; Yi, L. Optimization of grain import market layout in the context of food security: A study of soybean in China. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1549463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.Y.; Li, H.S.; Dai, X.; Li, J.D.; Liu, Y. An empirical analysis of global soybean supply potential and China’s diversified import strategies based on global agro-ecological zones and multi-objective nonlinear programming models. Agriculture 2025, 15, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.L.; Kang, M.Z.; Wang, X.J.; Hua, J.; Wang, H.Y.; Shen, X. Corn and soybean futures price intelligent forecasting based on deep learning. Smart Agric. 2022, 4, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.Y.; Pan, F.H.; Wang, C.M.; Li, J. Dynamic price discovery process of Chinese agricultural futures markets: An empirical study based on the rolling window approach. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 2019, 51, 664–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.L. Soybean futures price prediction based on CNN-LSTM model of Bayesian optimization algorithm. Highlights Business Econ. Manag. 2023, 16, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czudaj, R.L. The role of uncertainty on agricultural futures markets: Momentum trading and volatility. Stud. Nonlinear Dyn. Econom. 2020, 24, 20180054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, T.; Bao, Y.K. Research on soybean futures price prediction based on dynamic model average. China Manag. Sci. 2020, 28, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Xiong, T. Do bubbles alter contributions to price discovery? Evidence from the Chinese soybean futures and spot markets. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2019, 55, 3417–3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.T.; Tang, Z.P. Agricultural commodity futures prices prediction based on a new hybrid forecasting model combining quadratic decomposition technology and LSTM model. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1334098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhen, L.L.; Zhai, D.S. Forecasting for soybean futures based on multistage attention mechanism. Syst. Eng. 2023, 41, 148–158. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, H.J. Integrated prediction of financial time series based on deep learning. Stat. Inf. Forum 2020, 35, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Sun, T.; Cui, Y.P.; Wang, X.D.; Zhao, A.P.; Wang, T.; Wang, Z.F.; Yang, W.J.; Gu, G. Vegetable price prediction based on optimized neural network time series models. Smart Agric. 2025. Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- Manogna, R.L.; Dharmaji, V.; Sarang, S. Enhancing agricultural commodity price forecasting with deep learning. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 20903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikou, M.; Mansourfar, G.; Bagherzadeh, J. Stock price prediction using deep learning algorithm and its comparison with machine learning algorithms. Int. J. Intell. Syst. Account. Financ. Manag. 2019, 26, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Kim, J.; Im, H. A comparative study of bitcoin price prediction using deep learning. Mathematics 2019, 7, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.X.; Liu, Q.Y.; Hu, Y.R.; Liu, H.J. A study of futures price forecasting with a focus on the role of different economic markets. Information 2024, 15, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.T.; Pan, Y.; Liu, W.; Wang, J.Y. A prediction model for soybean meal futures price based on CNN-ILSTM-SA. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 111663–111672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.L.; French, N.; James, T.; Schillaci, C.; Chan, F.; Feng, M.; Lipani, A. Climate and environmental data contribute to the prediction of grain commodity prices using deep learning. J. Sustain. Agric. Environ. 2023, 2, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.X.; Hu, T.G.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Wang, J.M.; Long, M.S. TimesNet: Temporal 2D-variation modeling for general time series analysis. In Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2023), Kigali, Rwanda, 1–5 May 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, B.; Arık, S.Ö.; Loeff, N.; Pfister, T. Temporal fusion transformers for interpretable multi-horizon time series forecasting. Int. J. Forecast. 2021, 37, 1748–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, T.; Hu, Z.Y. Soybean futures price forecasting using dynamic model averaging: Do the predictors change over time? Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2019, 57, 1198–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, X.Y. Soybean Futures Price Prediction Based on Multimodal Data and LSTM Modeling. Master’s Thesis, Chongqing University of Technology, Chongqing, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Srichaiyan, P.; Tippayawong, K.Y.; Boonprasope, A. Forecasting soybean futures prices with adaptive AI models. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 48239–48256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.L.; Deng, H.L.; Wu, Q.F. Prediction of soybean price trend via a synthesis method with multistage model. Int. J. Agric. Environ. Inf. Syst. 2021, 12, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.D.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, T.H.; Wang, J.Y. Soybean futures price prediction model based on EEMD-NAGU. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 99328–99338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y. Forecast on price of agricultural futures in China based on ARIMA model. Asian Agric. Res. 2016, 11, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.H.; Gao, Q. High and low prices prediction of soybean futures with LSTM neural network. In Proceedings of the IEEE 9th International Conference on Software Engineering and Service Science (ICSESS), Beijing, China, 23–25 November 2018; pp. 140–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.M.; Liu, H.J.; Hu, Y.R. Soybean future prices forecasting based on LSTM deep learning. Prices Mon. 2021, 2, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, T.; Wang, Y.M. Nonlinear analysis and prediction of soybean futures. Agric. Econ. 2021, 67, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, W.Y.; Wang, L.; Zeng, Y.R. Text-based soybean futures price forecasting: A two-stage deep learning approach. J. Forecast. 2023, 42, 312–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.Y.; Liu, H.; Li, Y.F.; Duan, Z. An improved deep learning model for soybean future price prediction with hybrid data preprocessing strategy. Front. Agric. Sci. Eng. 2025, 12, 208–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.Y.; Houston, J. An intervention analysis on the relationship between futures prices of non-GM and GM contract soybeans in China. J. Bus. Econ. Policy 2015, 2, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Hayes, D.J. Price discovery on the international soybean futures markets: A threshold co-integration approach. J. Futures Mark. 2017, 37, 52–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; He, F.; Liu-Chen, B.A.; Li, Z.H. Price discovery and its determinants for the Chinese soybean options and futures markets. Financ. Res. Lett. 2021, 40, 101689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, A.; Rajib, P. The impact of Sino–US trade war on price discovery of soybean: A double-edged sword? J. Futures Mark. 2023, 43, 858–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Y.; Zhou, J.J. Correlation analysis of soybean futures prices between China and the United States: Based on wavelet analysis and Copula model. Prices Mon. 2024, 45, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Mu, Y.Y. Price fluctuation and linkage of soybean futures markets in China and the United States. Chin. Agric. Sci. Bull. 2017, 33, 159–164. [Google Scholar]

- He, L.Y.; Wang, R. A tale of two markets: Who can represent the soybean futures markets in China? Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 5, 826–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Xiong, T. Dynamic price discovery in Chinese agricultural futures markets. J. Asian Econ. 2021, 76, 101370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.C.; Cai, S.S.; Zhang, L.Y. Dynamic influence of international price fluctuation on soybean market price in China: Based on Bayesian-VAR model. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1594210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.R.; Yu, S.H.; Lv, S.X. Explainable soybean futures price forecasting based on multi-source feature fusion. J. Forecast. 2025, 44, 1363–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Insuwan, A.; Li, Z.R.; Tian, S.R. The dynamics of price discovery between the U.S. and Chinese soybean market: A wavelet approach to understanding the effects of Sino-US trade conflict and COVID-19 pandemic. Data Sci. Manag. 2024, 7, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Y.; Zhang, L.L.; Cheng, Q.Y.; Shi, S.; Niu, H.W. What drives risk in China’s soybean futures market? Evidence from a flexible GARCH-MIDAS model. J. Appl. Econ. 2022, 25, 454–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Chen, X.Y.; Ye, H.J.; Zhan, D.C. SOFTS: Efficient multivariate time series forecasting with series-core fusion. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.14197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Kong, W.H.; Leach, A.; Mathur, S.; Sen, R.; Yu, R. Long-term forecasting with TiDE: Time-series dense encoder. In Proceedings of the Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2024), Vienna, Austria, 7–11 May 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.A.; Li, C.L.; Yoder, N.C.; Arik, S.; Pfister, T. TSMixer: An All-MLP architecture for time series forecasting. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.06053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.J.; Kolter, J.Z.; Koltun, V. An empirical evaluation of generic convolutional and recurrent networks for sequence modeling. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.01271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.Q.; Nguyen, N.H.; Sinthong, P.; Kalagnanam, J. A time series is worth 64 words: Long-term forecasting with transformers. In Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2023), Kigali, Rwanda, 1–5 May 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, T.G.; Zhang, H.R.; Wu, H.X.; Wang, S.Y.; Ma, L.T.; Long, M.S. iTransformer: Inverted transformers are effective for time series forecasting. In Proceedings of the Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2024), Vienna, Austria, 7–11 May 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metin, A.; Kasif, A.; Catal, C. Temporal fusion transformer-based prediction in aquaponics. J. Supercomput. 2023, 79, 19934–19958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Wang, S.Y.; Ma, L.T.; Chu, Z.X.; Zhang, J.Y.; Shi, X.M.; Chen, P.Y.; Liang, Y.X.; Li, Y.F.; Pan, S.R.; et al. Time-LLM: Time series forecasting by reprogramming large language models. In Proceedings of the Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2024), Vienna, Austria, 7–11 May 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Chowdhury, R.R.; Gupta, R.K.; Shang, J.B. Large language models for time series: A survey. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souto, H.G. Charting new avenues in financial forecasting with TimesNet: The impact of intraperiod and interperiod variations on realized volatility prediction. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 255, 124851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakib, S.; Mahadi, M.K.; Abir, S.R.; Moon, A.M.; Shafiullah, A.; Ali, S.; Faisal, F.; Nishat, M.M. Attention-based models for multivariate time series forecasting: Multi-step solar irradiation prediction. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noman, F.; Alkawsi, G.; Alkahtani, A.A.; Al-Shetwi, A.Q.; Tiong, S.K.; Alalwan, N.; Ekanayake, J.; Alzahrani, A.I. Multistep short-term wind speed prediction using nonlinear auto-regressive neural network with exogenous variable selection. Alex. Eng. J. 2021, 60, 1221–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Andreu, F.J.; López-Morales, J.A.; Hernández-Guillen, Z.; Carrero-Rodrigo, J.A.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, M.; Atenza-Juárez, J.F.; Erena, M. Deep learning-based time series forecasting models evaluation for the forecast of chlorophyll a and dissolved oxygen in the mar menor. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, F.; Tuan, F.C. China Currency Appreciation Could Boost U.S. Agricultural Exports; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. Available online: https://ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details?pubid=40462&utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Bandyopadhyay, A.; Rajib, P. The asymmetric relationship between Baltic Dry Index and commodity spot prices: Evidence from nonparametric causality-in-quantiles test. Miner. Econ. 2023, 36, 217–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Futures Product | Models/Algorithms | Exogenous Variable | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| CN Soy Fut | PM: dynamic model averaging (DMA) and dynamic model selection (DMS) framework BM: Time-Varying Parameter (TVP); Recursive OLS-AR (3); Recursive OLS-All predictors; Random walk | Chinese soybean futures price; Chinese soybean net import; Chinese soybean spot price; U.S. soybean futures price; Trading Volume in Chinese soybean futures markets; Turnover rate in Chinese soybean futures markets; WTl Crude oil spot price; Exchange rate of USD/CNY; Baltic dry index | [27] |

| CN Soy Fut (#1) | PM: BO-CNN-LSTM BM: BP neural network; LSTM; CNN-LSTM | Opening price (OP); Highest price (HP); Lowest price (LP); Closing price (CP); Trading volume (TV); Transaction amount (TA); Open interest (OT) | [11] |

| CN Soy Fut (#1) | PM: LSTM BM: GRU; RNN | OP; HP; LP; CP; TV; TA; OT; 10-day moving average; Moving average convergence divergence; Bias ratio; Larry Williams’ percent range; Relative strength index; Rate of change; Domestic and international news; et al. | [28] |

| US Soy Fut | PM: Elastic Net; Support Vector Regression (SVR); Decision Tree; Random Forest; Gradient Boosting; LSTM; ANN; Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average with Exogenous Variables (ARIMAX); Seasonal Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average with exogenous variables (SARIMAX) | US dollar index; Gold (XAU/USD); Crude oil (WTI/USD); Fertilizers price index; Freight rates; Shipping rates; Weather report; Soybean planting chart; Agriculture planting chart; Bulk grain prices; Soybean future price; Import rate | [29] |

| CN Soy Fut | PM: LSTM BM: RNN; GRU; ANN | N/A | [30] |

| CN Soy Fut (#1) | PM: Attention-LSTM BM: Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA); SVR; LSTM | N/A | [9] |

| CN Soy Fut | PM: Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition (EEMD) and New Attention Gate Unit (NAGU) model (EEMD-NAGU) BM: SVR; LSTM; GRU; NAGU; EEMD-LSTM; EEMD-GRU; Attention-LSTM; Attention-GRU; EEMD-Attention-LSTM; EEMD-Attention-GRU; | Dow Jones Industrial Index (DJIA); S&P Dow Jones Indices Index (S&P 500); National Association of Securities Dealers Automated Quotations Index (NASDAQ) | [31] |

| CN Soy Fut | PM: ARIMA | N/A | [32] |

| CN Soy Fut | PM: LSTM BM: BP | N/A | [33] |

| CN Soy Fut (#1) | PM: Multistage Attention Network (MAN) BM: VAR; LSTM | CP; OP; HP; LP; Price fluctuation; Temperature index; Air pressure index; Precipitation index; Search index | [16] |

| CN Soy Fut Index | PM: Multi-layer LSTM BM: ARIMA; Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP); SVR | N/A | [34] |

| US Soy Fut | PM: chaotic artificial neural network (CANN) BM: ANN | N/A | [35] |

| CN Soy Fut | PM: Two-Stage Hybrid-LSTM BM: univariate LSTM; multivariate LSTM; eXtreme Gradient Boosting | Social media text feature | [36] |

| CN Soy Fut (#1) US Soy Fut IT Soy ETF | PM: ICEEMDAN-LZC-BVMD-SSA-DELM (a hybrid model composed of improved complete ensemble empirical mode decomposition with adaptive noise (ICEEMDAN); Lempel-Ziv complexity (LZC) determination method; variational mode decomposition optimized by beluga whale optimization (BWO) algorithm (BVMD); sparrow search algorithm (SSA); deep extreme learning machine (DELM)) BM: ELM; radial basis function (RBF); deep belief network (DBN); LSTM; GRU; DELM; SSA-DELM; ICEEMDAN-DELM; ICEEMDAN-SSA-DELM; VMD-DELM; BVMD-DELM; BVMD-SSA-DELM; ICEEMDAN-LZ-BVMD-DELM | N/A | [37] |

| Variable | Description | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target variables | CSFP | China’s DCE No. 2 soybean futures price | Dalian Commodity Exchange Data Center |

| Exogenous variables | USFP | U.S. CBOT soybean futures price | China Grain and Oil Business Network Data Center |

| ER | Exchange rate of USD/CNY | China Foreign Exchange Trade System | |

| SFS | Soybean Freight Cost (Santos, Brazil–North China) | China Grain and Oil Business Network Data Center | |

| SFP | Soybean Freight Cost (Paranaguá, Brazil–China) | China Grain and Oil Business Network Data Center | |

| SFA | Soybean Freight Cost (Argentina–Northern China) | China Grain and Oil Business Network Data Center | |

| SFG | Soybean Freight Cost (U.S. Gulf Coast -China) | China Grain and Oil Business Network Data Center | |

| SFN | Soybean Freight Cost (U.S. Pacific Northwest–China) | China Grain and Oil Business Network Data Center | |

| Variable | Mean | Max | Min | Standard Deviation | Coefficient of Variation | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSFP | 3957.00 | 5751.00 | 2709.00 | 655.29 | 0.17 | CNY/T |

| USFP | 2795.26 | 4289.14 | 1906.37 | 541.60 | 0.19 | CNY/T |

| ER | 6.70 | 7.81 | 6.09 | 0.39 | 0.06 | - |

| SFS | 45.67 | 143.00 | 13.70 | 22.78 | 0.50 | USD/T |

| SFP | 44.39 | 140.06 | 12.20 | 22.40 | 0.50 | USD/T |

| SFA | 48.88 | 140.00 | 21.10 | 21.14 | 0.43 | USD/T |

| SFG | 51.86 | 139.00 | 20.00 | 20.04 | 0.39 | USD/T |

| SFN | 29.41 | 100.00 | 11.00 | 13.37 | 0.45 | USD/T |

| Framework | Models/Algorithms | MAE | MAPE | RMSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MLP | SOFTS | 140.9926 | 0.0407 | 187.8455 |

| TiDE | 388.5366 | 0.1118 | 459.8178 | |

| TSMixerx | 343.5763 | 0.0993 | 419.1471 | |

| CNN | TCN | 216.5880 | 0.0631 | 291.8825 |

| TimesNet | 147.3828 | 0.0412 | 184.7208 | |

| Transformer | PatchTST | 206.5781 | 0.0600 | 270.9045 |

| iTransformer | 133.4171 | 0.0387 | 186.6440 | |

| TFT | 395.0730 | 0.1157 | 558.9772 | |

| LMM | Time-LLM | 438.0608 | 0.1260 | 505.6690 |

| RNN | LSTM | 237.9026 | 0.0653 | 264.0886 |

| External Variables | Model | ΔMAE (%) | ΔMAPE (%) | ΔRMSE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| USFP | TFT | +55.4 | +55.9 | +59.0 |

| TiDE | +44.8 | +44.4 | +35.9 | |

| TSMixer | −2.1 | −1.0 | +5.6 | |

| TCN | −123.2 | −122.5 | −127.0 | |

| LSTM | −8.9 | −13.5 | −13.6 | |

| ER | TFT | +56.5 | +57.2 | +60.5 |

| TSMixer | +19.2 | +19.7 | +24.7 | |

| TiDE | −20.3 | −20.0 | −18.7 | |

| TCN | −79.7 | −76.9 | −49.9 | |

| LSTM | −15.9 | −18.5 | −15.3 | |

| SF | TFT | +57.6 | +57.9 | +59.9 |

| TSMixer | −1.6 | −1.8 | −4.0 | |

| TiDE | −1.9 | −2.0 | −3.1 | |

| TCN | −153.4 | −146.4 | −128.3 | |

| LSTM | −100.9 | −104.1 | −107.0 | |

| USFP + ER + SF | TFT | +59.6 | +59.9 | +61.3 |

| TiDE | +37.0 | +37.5 | +36.8 | |

| TSMixer | +19.6 | +19.8 | +16.8 | |

| TCN | −160.2 | −152.6 | −103.0 | |

| LSTM | −13.9 | −13.7 | −11.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dai, X.; Chen, L.; Hou, Y.; Ning, X.; Zhao, W.; Cui, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, M. A Comparative Study of Neural Network Models for China’s Soybean Futures Price Forecasting. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2586. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242586

Dai X, Chen L, Hou Y, Ning X, Zhao W, Cui Y, Liu J, Wang M. A Comparative Study of Neural Network Models for China’s Soybean Futures Price Forecasting. Agriculture. 2025; 15(24):2586. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242586

Chicago/Turabian StyleDai, Xin, Li Chen, Ying Hou, Xiaohan Ning, Wenqiang Zhao, Yunpeng Cui, Juan Liu, and Mo Wang. 2025. "A Comparative Study of Neural Network Models for China’s Soybean Futures Price Forecasting" Agriculture 15, no. 24: 2586. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242586

APA StyleDai, X., Chen, L., Hou, Y., Ning, X., Zhao, W., Cui, Y., Liu, J., & Wang, M. (2025). A Comparative Study of Neural Network Models for China’s Soybean Futures Price Forecasting. Agriculture, 15(24), 2586. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242586