1. Introduction

As one of the three major grain crops, maize accounted for approximately 43% of global cereal production in 2024, with China contributing 24% to the world’s total maize output [

1]. Currently, China primarily relies on maize imports, facing a substantial domestic supply-demand gap and relatively high dependency on the international market, indicating a significant disparity between domestic production and demand [

2]. Beyond yield increases from expanded planting area, enhancing yield per unit area remains crucial for substantially boosting maize production [

3].

High-quality and efficient single-seed precision seeding is crucial for enhancing maize yield per unit area. Currently, domestic precision seeders primarily employ a seed metering mechanism driven by ground wheels via sprockets and chains; however, as operational speed increases, ground wheel slippage becomes more pronounced, significantly compromising seed spacing uniformity and severely limiting yield potential [

4,

5,

6]. To address this issue, researchers have conducted in-depth studies on speed measurement technologies and drive methods for electric drive seeders, where the accuracy of forward speed monitoring and the dynamic response of seeding motor speed control fundamentally determine seed spacing uniformity [

7,

8]. While various speed measurement methods—such as ground wheel encoders, Hall effect sensors, satellite positioning modules, and ground speed radar—are currently available, each exhibits certain limitations in practical application, making it challenging to maintain measurement accuracy across diverse working conditions and operational states [

9,

10]. Consequently, electric drive seeding systems face challenges including hysteresis in motor speed control, excessive overshoot, and susceptibility to interference, posing significant obstacles to the broader adoption and application of electric drive seeding technology [

11].

The core of speed acquisition lies in ensuring the real-time performance and accuracy of speed measurement to achieve real-time and accurate monitoring of the tractor’s forward speed [

12]. Jafari et al. designed a motor closed-loop control system based on dual-encoder speed measurement, which acquires the seeder’s operational speed in real-time via a ground wheel encoder and improves seed spacing uniformity by utilizing motor speed feedback from an encoder installed on the output shaft of the seeding motor [

13]. Liao et al. developed a speed-adaptive seeding control system for oilseed rape with switchable speed measurement modes, employing both a ground wheel encoder and a BeiDou receiver to obtain the forward speed during low- and medium-high-speed operations, respectively. Field tests showed that within an operational speed range of 1.44–7.99 km/h, the system achieved a seeding rate error of less than 3.9% and a qualified seed spacing index greater than 84%, meeting the requirements for speed-adaptive seeding [

14]. The Seedstars

TM 2 seeding control system produced by John Deere in the United States integrates three speed measurement methods: GPS, radar, and photoelectric sensors. It utilizes photoelectric sensors to calibrate speed information provided by the radar or GPS, ensuring that the system can maintain normal operation for a short period in case of GPS or radar signal loss [

15]. The ETR series intelligent electric drive pneumatic seeders manufactured by Zhengzhou Longfeng Company incorporate a dual speed measurement system combining the Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) and a speed radar. By dynamically adjusting the weighting of GNSS and speed radar data, the system achieves complementary advantages of the two methods; however, during low-speed turning maneuvers, coupling interference between GNSS carrier phase noise and the Doppler sensitivity threshold of the radar leads to significant fluctuation amplitude in the fused speed, thereby adversely affecting seed spacing uniformity [

16]. XIE et al. compared and analyzed the effects of three speed measurement methods—GNSS receiver, Doppler radar, and incremental rotary encoder—on the monitoring accuracy of seed spacing. Experimental results indicated that the speed monitoring values from all three methods were strongly correlated with the real-time monitored seed spacing values (correlation coefficient R > 0.95), and considering the cost and installation requirements of the three speed measurement devices, they recommended prioritizing the use of a GNSS receiver as the speed measurement device for electric drive precision seeders [

17]. Compared with sensor-based speed measurement methods, GNSS speed measurement remains unaffected by seeder structure or ground surface conditions, and its capability to provide multidimensional information including velocity, position, and time has led to its expanding applications in agricultural sectors such as variable-rate seeding, precision fertilization, and pest control [

18,

19]. RTK-GNSS, leveraging carrier phase differential technology, overcomes the accuracy limitations of conventional GNSS by effectively mitigating errors caused by multipath effects and ionospheric delay, achieving centimeter-level dynamic positioning accuracy. However, it still suffers from speed measurement lag due to update frequency constraints during maneuvering operations, with additional performance degradation under signal occlusion or adverse weather conditions [

20,

21,

22]. Accelerometers can directly acquire implement acceleration data with advantages including stable performance and high sampling frequency. Comparative analysis of RTK-GNSS receivers and accelerometers reveals complementary strengths in absolute accuracy versus dynamic response. By implementing fusion algorithms to integrate real-time data from both sources—using high-frequency accelerometer readings to compensate for RTK-GNSS signal gaps—the latency issues inherent in RTK-GNSS speed measurement can be mitigated, thereby enhancing speed measurement precision under complex operating conditions.

The key to electric drive seeding technology lies in dynamically adjusting the rotational speed of the seeding motor in real-time based on the acquired forward speed of the tractor to ensure uniformity of seed spacing. Cay et al. utilized a brushless DC motor to drive the seed meter and completed command transmission between the Arduino master controller and individual seeding units via CAN bus; experimental results demonstrated that compared with the traditional ground wheel drive method, this system increased the qualified seed spacing index by 2.5% and reduced the coefficient of variation of qualified seed spacing by 0.18% [

23,

24]. Ranta et al. designed an electric drive seed meter based on a belt drive structure, where a laterally mounted seeding motor transmits power to the seed shaft through a synchronous belt. Test results indicated that this electric drive seed meter increased the operational speed of the seeder to 10 km/h while effectively eliminating the impact of ground wheel slippage on seeding quality, and additionally, each motor can be controlled independently, laying the foundation for the implementation of section control and variable-rate seeding technologies [

25]. The Tempo R series trailed high-speed seeder produced by Sweden’s VADERSTAD Company, through the synergistic application of the E-Control system and ISOBUS terminal, enables precise section control and variable rate seeding functions, and during turning operations, the curve compensation function ensures uniform seed spacing, effectively improving seeding quality [

26]. The 2160 no-till precision planter manufactured by the U.S. Case Company adopts the vSet air suction seed meter developed by Precision Planters in combination with the vDrive servo motor, driving the seed meter via gear engagement, which not only achieves independent control of individual seeding units but also effectively shortens the overall length of the drive chain and optimizes the structural layout [

27]. HE et al. designed an electric drive control system for seed meters based on a PID control strategy, using Hall sensors to monitor the speed of the brushless DC motor and employing a trial-and-error method to tune the PID parameters to achieve closed-loop control of the motor speed. In a step response test where the motor speed increased from 0 r/min to 24 r/min, the system’s overshoot was 1.56%, verifying the superiority of the PID control strategy in enhancing the stability of motor speed control [

28]. YU et al. designed an electronically controlled peanut seeding system based on a fuzzy PID control strategy, which uses a servo motor to drive the seed shaft and determines the initial values for the fuzzy PID control through a trial-and-error method; compared with traditional PID control, this system offers advantages in overshoot suppression [

29].

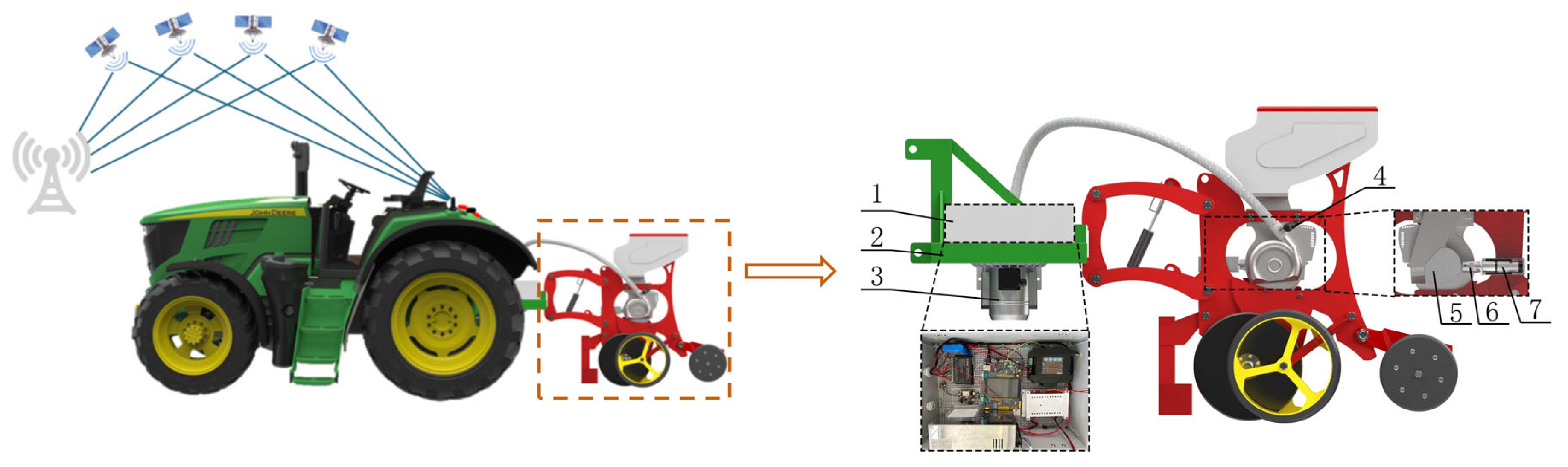

Aiming at the problems of ground wheel slippage, drive chain skipping, and breakage that commonly occur in existing maize precision planters during high-speed operation, which make it difficult to meet the requirements of precision seeding at high speeds, an air-suction electric drive precision seeding control system was designed. This system constructs a multi-rate KF-RTS smoothing fusion algorithm that integrates RTK-GNSS and accelerometer data to provide more accurate speed information for the seeding operation. To enhance the dynamic response speed and steady-state accuracy of the seeding motor, a Kalman filter-based fuzzy PID motor control strategy is proposed, providing theoretical foundation and technical support for high-performance control of the seeding motor.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Simulation Results and Analysis of the Fusion Algorithm

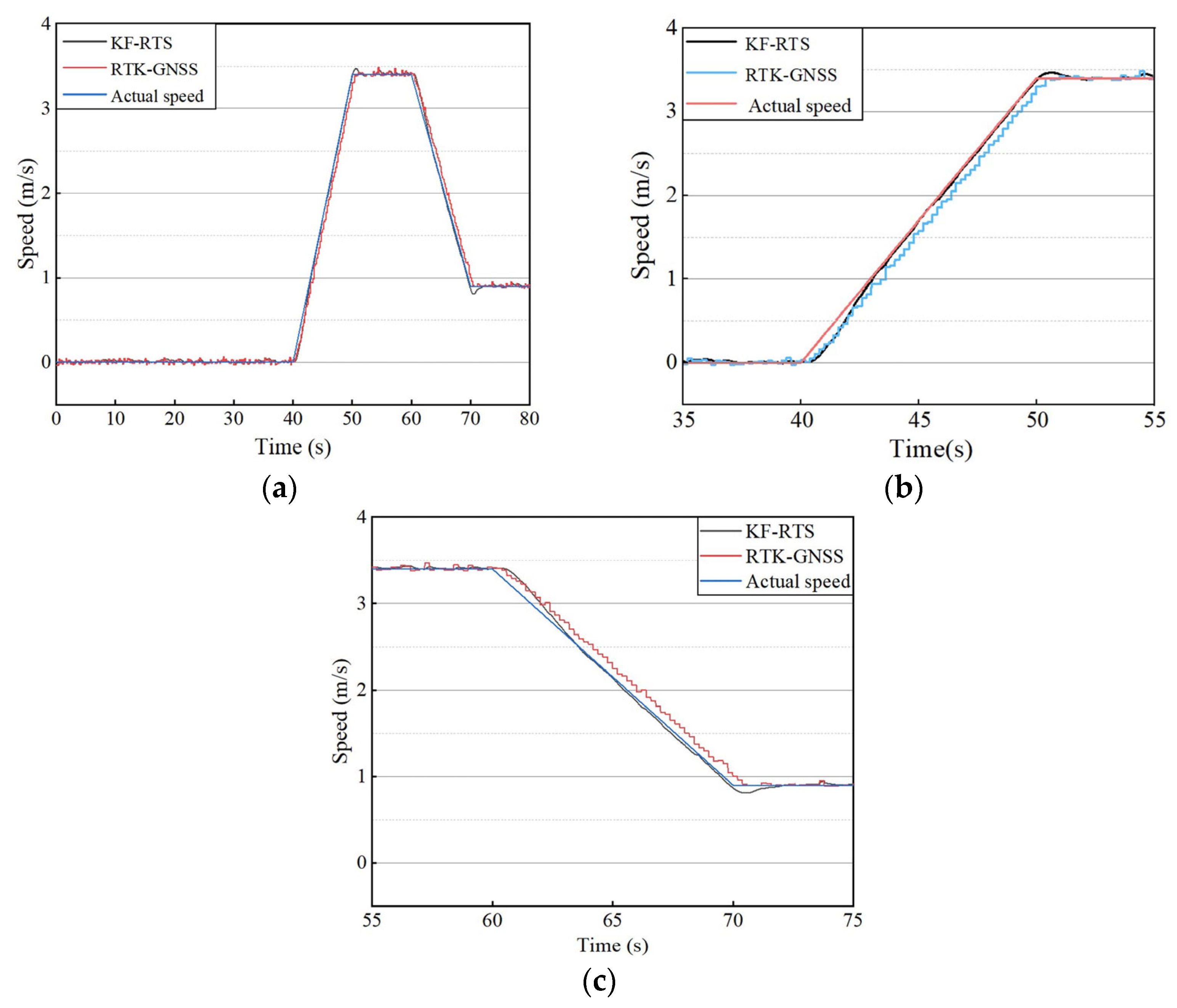

The results of KF-RTS fusion speed measurement and RTK-GNSS speed measurement obtained from simulation tests are shown in

Figure 11, where

Figure 11b,c corresponds to the acceleration phase and deceleration phase of the tractor’s travel.

As shown in

Figure 11b, during the tractor acceleration phase, the RTK-GNSS measured values are lower than the true values. According to

Figure 11c, during the tractor deceleration phase, the RTK-GNSS measured values exceed the true values. This indicates a significant lag phenomenon in RTK-GNSS speed measurement during tractor acceleration and deceleration processes, primarily caused by the low data update frequency of the RTK-GNSS receiver. In comparison, the KF-RTS fusion speed measurement results demonstrate closer alignment with the true velocity, confirming that the integrated approach using accelerometer and RTK-GNSS data effectively mitigates the speed measurement delay during variable-speed operations.

Figure 12 presents the velocity errors between both KF-RTS fusion speed measurement and RTK-GNSS speed measurement relative to the true velocity.

Table 9 compares the speed measurement errors between RTK-GNSS and KF-RTS under three motion states: constant velocity, acceleration, and deceleration.

Under constant, accelerating, and decelerating motion conditions, the KF-RTS fusion speed measurement demonstrates significant optimization in speed measurement accuracy compared to RTK-GNSS speed measurement. During constant-speed conditions (50–60 s), KF-RTS reduced the mean error, standard deviation, and maximum error by 43.07%, 50.57%, and 72.65%, respectively, effectively suppressing the accumulation of random noise in steady-state motion and improving seed spacing uniformity. Under acceleration, abrupt changes in acceleration caused cumulative errors in RTK-GNSS due to speed measurement lag, while KF-RTS reduced the mean error, standard deviation, and maximum error by 83.68%, 62.87%, and 77.45%, respectively, effectively mitigating the speed measurement delay of RTK-GNSS and avoiding the issue of reduced seed spacing caused by speed underestimation during acceleration. During deceleration, abrupt changes in acceleration similarly led to cumulative errors in RTK-GNSS due to speed measurement lag, while KF-RTS reduced the mean error, standard deviation, and maximum error by 76.08%, 48.44%, and 34.77%, respectively, effectively alleviating the speed measurement delay of RTK-GNSS and preventing the issue of increased seed spacing resulting from speed overestimation during deceleration. Additionally, the reversal of error direction during deceleration indicates that the linear state model of the traditional Kalman filter struggles to accurately describe nonlinear dynamic processes.

The aforementioned test results demonstrate that under steady-state conditions, the KF-RTS fusion-based speed measurement effectively suppresses the influence of both random and systematic errors on speed measurement accuracy compared to RTK-GNSS speed measurement, yielding results closer to the true values. During acceleration and deceleration states, the KF-RTS fusion-based speed measurement responds more rapidly to speed variations, effectively reducing error accumulation caused by acceleration changes and thereby providing more accurate speed data. In summary, compared with RTK-GNSS speed measurement, the multi-rate KF-RTS fusion-based speed measurement effectively mitigates the latency inherent in RTK-GNSS speed measurement, significantly enhances speed measurement accuracy, and improves seed spacing uniformity.

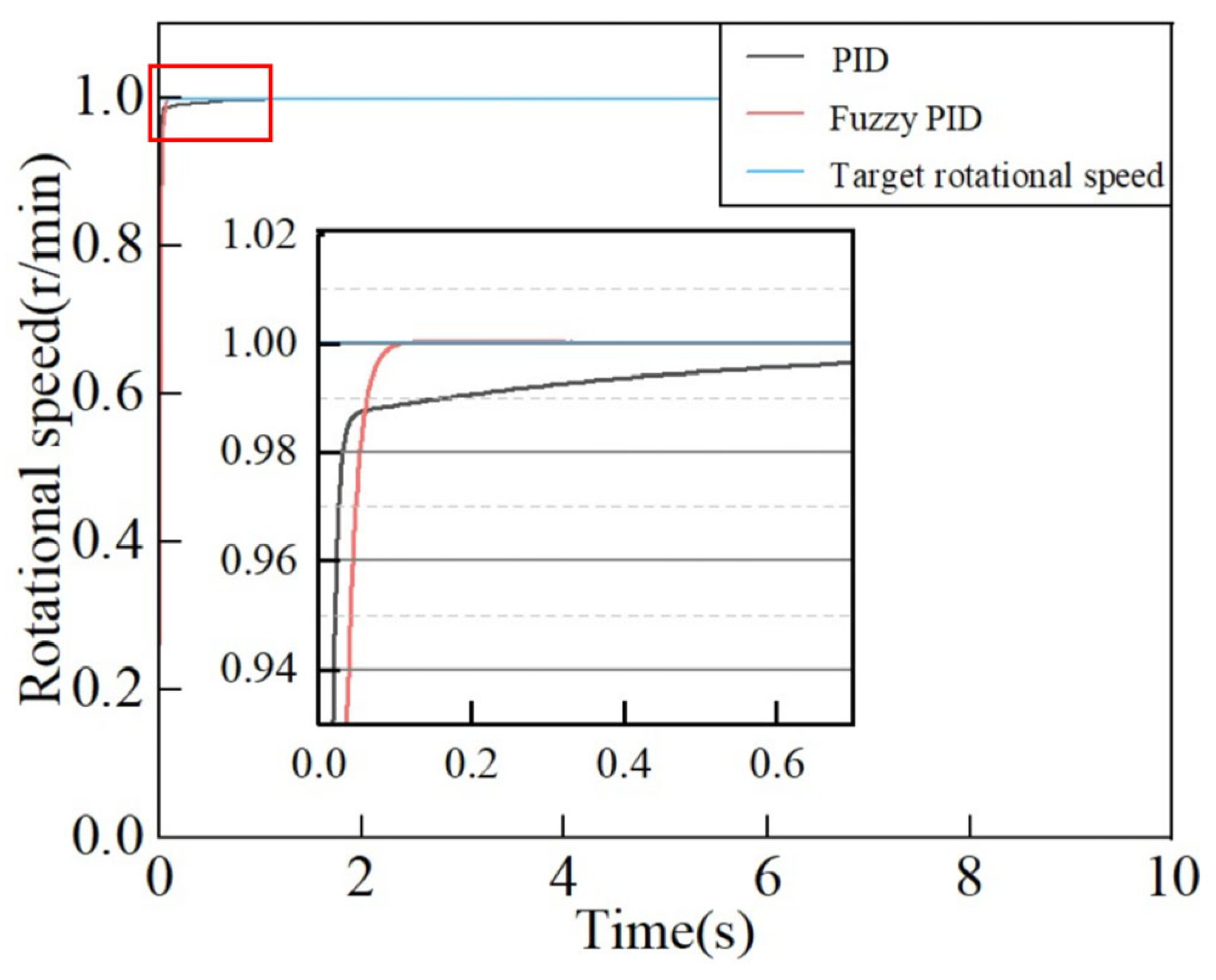

3.2. Simulation Results and Analysis of the Kalman Filter-Based Fuzzy PID Control System

Figure 13 presents the system step response curves for both PID control and fuzzy PID control, where neither control method exhibited overshoot. However, the fuzzy PID control demonstrated significantly superior performance in dynamic response characteristics compared to conventional PID control. The response curve of the fuzzy PID controller rapidly converged to the target value within 0.1 s, whereas the PID control response curve required 1 s to reach the target value due to its fixed parameters—indicating that the fuzzy PID control reduced the convergence time to one-tenth of that required by PID control. Test results confirm that the fuzzy PID controller’s capability for dynamic parameter adjustment yields superior performance in both response speed and control accuracy. This makes fuzzy PID control particularly valuable for control systems requiring rapid response characteristics.

Figure 14 shows the step response curves of the fuzzy PID control system before and after implementing Kalman filtering. Without Kalman filtering, the response curve exhibited significant fluctuations with substantial noise interference, whereas with Kalman filtering, the steady-state error of the response curve was controlled within 0.55%. The test results demonstrate that Kalman filtering effectively suppresses noise interference in the fuzzy PID control system, significantly enhancing the system’s noise immunity.

3.3. Results and Analysis of Wind Pressure Test

The results of the two-factor test involving operational speed and working air pressure are presented in

Table 10. To facilitate more intuitive analysis of the effects of operational speed and working air pressure on the test evaluation metrics, the test data were visualized using Origin (2022) software, with the results shown in

Figure 15.

As shown in

Figure 15, the miss index, multiple index, and precision index exhibit certain regularities with variations in operating air pressure and operating speed. At each level of operating air pressure, the precision index of the seed meter initially increases and then decreases as the operating speed rises, whereas the miss index demonstrates the opposite trend by first decreasing and then increasing, and the multiple index shows a continuous declining trend throughout.

When the working air pressure of the seed meter was set at 3 kPa and the operational speed reached 12 km/h, the qualified index decreased significantly with a sharp increase in the miss index. This phenomenon indicates that the current working air pressure is insufficient for the seed meter to effectively adsorb seeds, necessitating an increase in air pressure to ensure seeding quality. Test data demonstrated that at an operational speed of 12 km/h, as the working air pressure increased from 3 kPa to 5.5 kPa, the qualified index remarkably improved from 84.35% to 95.35%. When the working air pressure was maintained within the range of 4.5 to 5.5 kPa, the qualified index consistently remained above 90%, while the miss index and multiple index were controlled below 5% and 4%, respectively, indicating that the seed meter can maintain high seeding accuracy and stability within this air pressure range.

ANOVA was performed on the aforementioned test data to determine the effects of working air pressure, forward speed, and their interaction on each evaluation metric, with the results presented in

Table 11.

ANOVA results indicated that both the operating air pressure and forward speed, as well as their interaction, had a highly significant effect on all evaluation indicators.

Based on experimental research investigating the effects of operating air pressure and forward speed on seeding quality, data analysis was conducted to determine the optimal control parameters for the precision index. Specifically, when the forward speed is determined, it should be matched with its corresponding operating air pressure to ensure the seeder operates under optimal working conditions. To quantify the relationship between operating air pressure and forward speed, a surface fitting analysis was performed on the experimental data using the Poly2D fitting model in Origin software, with the resulting fitted surface shown in

Figure 16.

The multiple linear regression equation for the qualified index, constructed based on the Poly2D fitting model, is given as Equation (12).

where

x represents the forward speed and

y denotes the operating air pressure, with a correlation coefficient of

R = 0.81.

Based on Equation (12), the required operating air pressure values for the seed meter at different forward speeds were determined, as presented in

Table 12.

3.4. Motor Speed Control Test Results and Analysis

The motor speed response curve obtained from the motor speed regulation test is shown in

Figure 17.

The motor speed regulation performance indicators are presented in

Table 13. Within the operational speed range of 6–12 km/h, the system demonstrated a rise time of 0.30–0.50 s and a settling time of 0.32–0.54 s, with the complete dynamic response consistently controlled within 0.54 s. These results indicate that the motor speed regulation system possesses rapid response capability, enabling quick adaptation to target speeds within short timeframes, which is crucial for enhancing the operational efficiency and seeding uniformity of electric-drive precision planters. Furthermore, across all tested operational speeds, the system overshoot remained below 0.36%, reflecting minimal deviation between peak and target speeds during regulation processes, thereby ensuring smooth convergence to desired operating conditions and effectively preventing speed fluctuations induced by excessive overshoot. Simultaneously, the steady-state error was maintained within 1.06%, showing a decreasing trend with increasing operational speed, confirming the system’s high control precision in stabilized conditions and its capability to meet the stringent speed control accuracy requirements for precision planting operations.

3.5. Field Test Results and Analysis

A statistical analysis was conducted on the seed spacing from eight seedbed strips following the operation of the air-suction electric drive precision seeding control system utilizing two speed measurement methods, and the corresponding seeding performance metrics under different speed measurement methods were calculated as presented in

Table 14.

As shown in

Table 14, when using the RTK-GNSS speed measurement method, the precision index of the seeder reaches no less than 90.12%, while with the KF-RTS fusion speed measurement method, the precision index increases to no less than 94.11%. Both speed measurement methods satisfy the requirement of achieving a precision index no less than 80% for maize planters. As the operating speed increases from 6 km/h to 12 km/h, the precision index of both speed measurement methods shows a declining trend. However, the KF-RTS fusion method demonstrates a reduction of only 2.58% (from 96.69% to 94.11%), which is significantly smaller than the 4.24% reduction observed with the RTK-GNSS method. These results indicate that the KF-RTS fusion speed measurement method exhibits better adaptability under high-speed operating conditions. At operating speeds of 6 km/h, 8 km/h, 10 km/h, and 12 km/h, the seeder equipped with the KF-RTS fusion method shows improvements in the precision index of 2.33%, 2.80%, 3.12%, and 3.99%, respectively, compared to the RTK-GNSS method. Additionally, the coefficient of variation of seed spacing is reduced by 3.85%, 4.36%, 6.63%, and 6.93%, respectively. These findings demonstrate that the air-suction electric drive precision seeding control system based on the KF-RTS fusion speed measurement method exhibits significant advantages in seeding performance compared to the system using RTK-GNSS speed measurement. This improvement can be attributed to the faster response of the KF-RTS fusion method to changes in tractor speed during acceleration and deceleration processes, which reduces the accumulation of speed measurement errors caused by acceleration fluctuations. By providing more accurate speed data for the control of the seeding motor speed, the fusion method enhances both the precision index and the uniformity of qualified seed spacing.