Calcium–Silicon–Magnesium Synergistic Amendment Enhances Cadmium Mitigation in Oryza sativa L. via Soil Immobilization and Nutrient Regulation Dynamics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Soil Characterization

2.2. Field Experiment

2.3. Sampling and Analysis

2.3.1. Soil Sampling and Analysis

- Exc-Cd: An amount of 1.00 g soil was extracted with 8 mL MgCl2 (1.0 mol/L) in a 50 mL centrifuge tube for 1 h. The suspension was centrifuged at 4000 r for 10 min and the subsequent collection of the supernatant.

- Car-Cd: An amount of 8 mL CH3COONa (1.0 mol/L, pH = 5.0) was used to extract the residue from Step 1 for 5 h. The suspension was then centrifuged at 4000 r for 10 min, and the supernatant collected.

- FeMnOx-Cd: An amount of 20 mL NH2OH·HCl (0.04 mol/L) was used to extract the residue from Step 2 at 96 °C for 6 h. The suspension was then centrifuged at 4000 r for 10 min, and the supernatant collected.

- OM-Cd: An amount of 5 mL 30% H2O2 and 3 mL 0.02 mol/L HNO3 (mixed solution pH = 2.0) were added to the residue from Step 3 at 85 °C for 2 h. Then 5 mL of 30% H2O2 extract was added and extracted at 85 °C for 3 h, followed by 5 mL of a solution containing 20% (v/v) HNO3 and 3.2 mol/L CH3COONH4. The suspension was then centrifuged at 4000 r for 10 min, and the supernatant collected.

- R-Cd: The residue from Step 4 was dried and digested in a mixed acid solution of HCl-HNO3-HF-HClO4.

2.3.2. Plant Sampling and Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Inhibitory Effect of Ca-Si-Mg Composite Soil Amendment (CSM) on Cd Accumulation in Rice

3.2. Impacts of Passivators on Soil Available Cd Content and Speciation Transformation

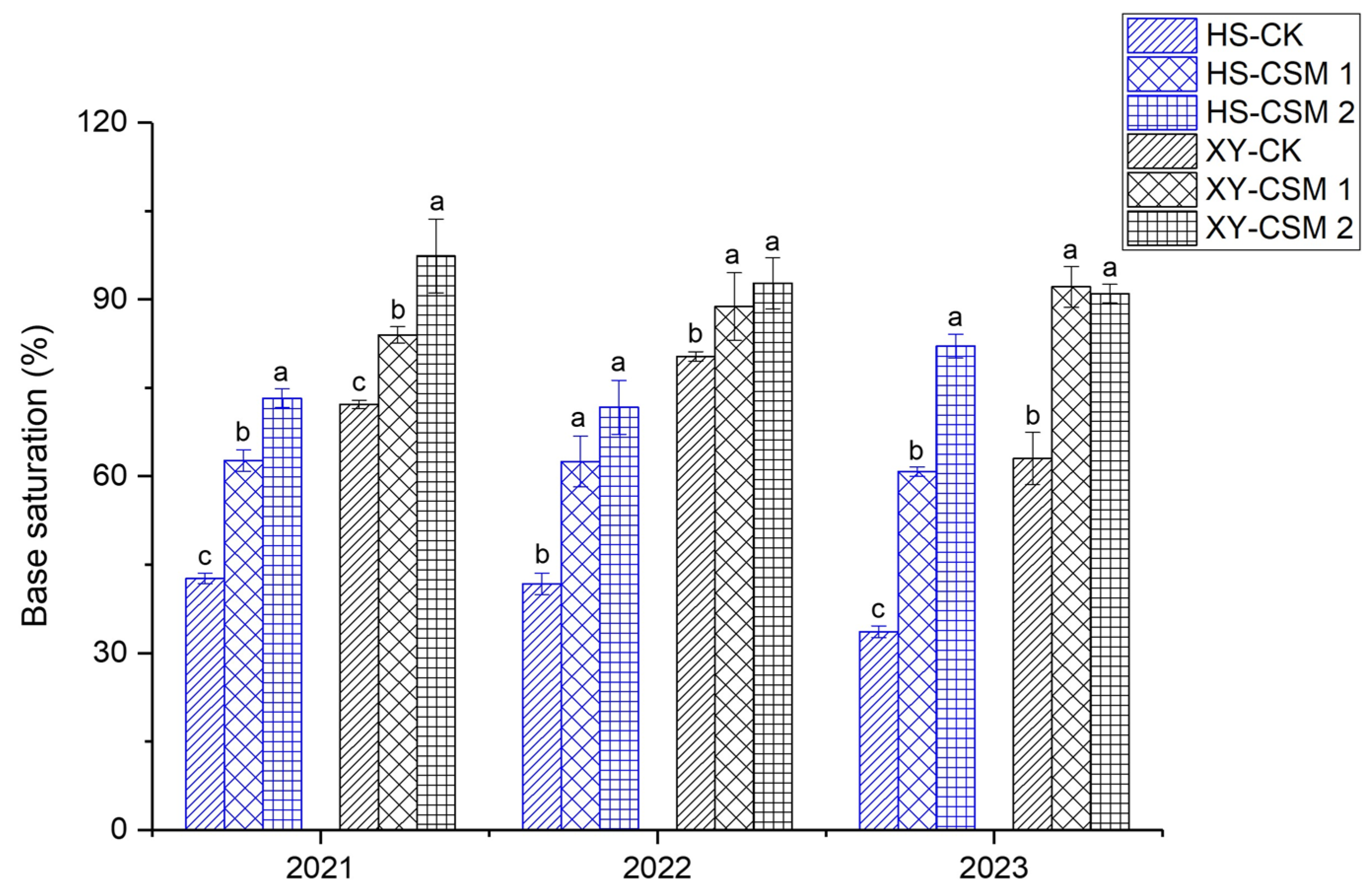

3.3. Influence of CSM-Mediated Passivation on Soil Physicochemical Properties

3.4. Potential Effects of Various Physical and Chemical Factors in Soil on Cd Toxicity and Plant Growth

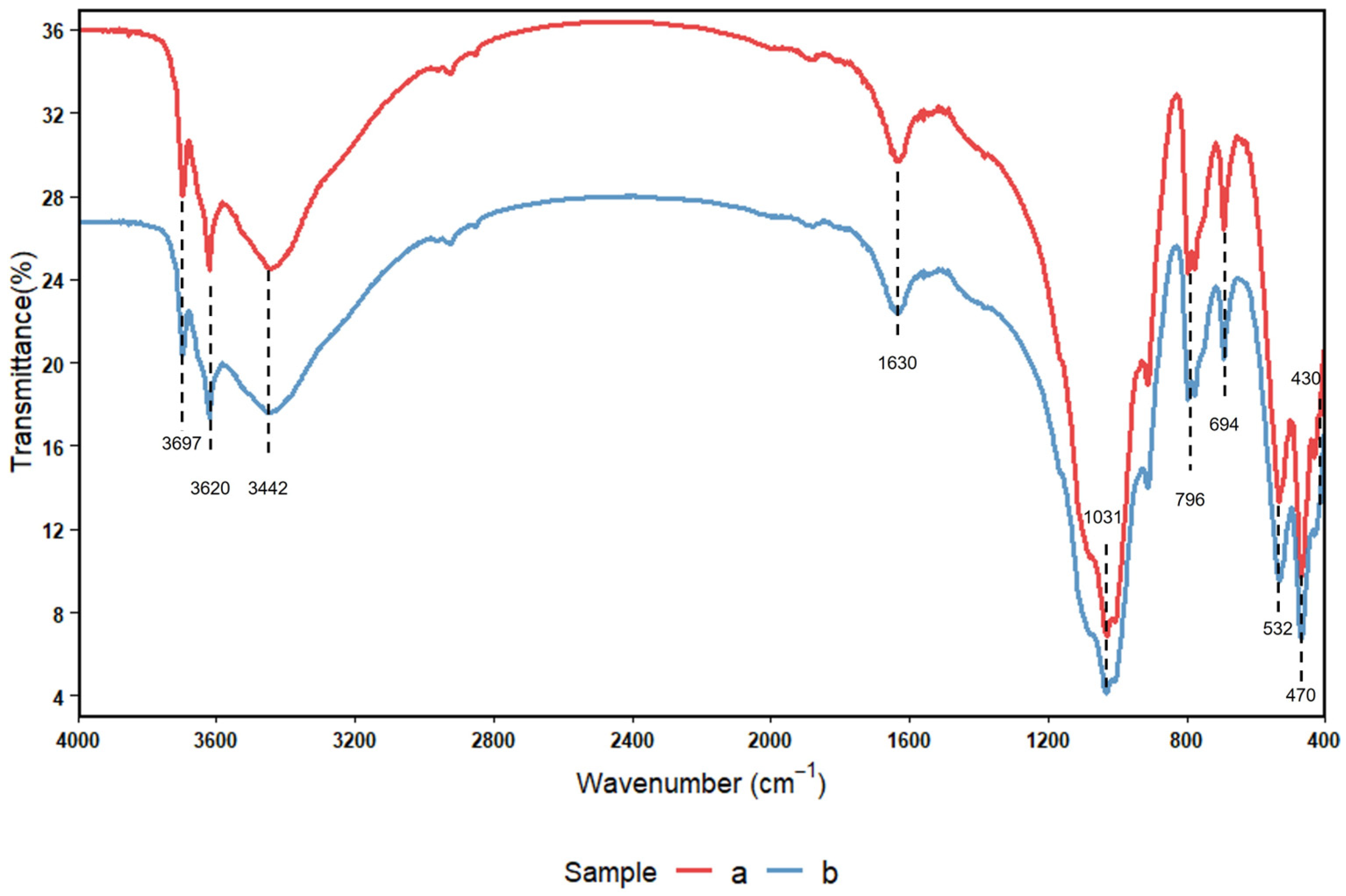

3.5. FTIR Spectroscopic Characterization of Soil Functional Group Composition and Relative Abundance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lu, T.; Ge, W.; Li, A.; Deng, S.; Min, T.; Qiu, G. Endogenous silicon-activated rice husk biochar prepared for the remediation of cadmium-contaminated soils: Performance and mechanism. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 362, 125030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, X.; Yu, L.; Wang, T.; Wang, J.; Liu, T. Review of soil heavy metal pollution in China: Spatial distribution, primary sources, and remediation alternatives. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 181, 106261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.; Xiao, C.; Cheng, W.; Yu, H.; Liu, J.; Liu, G.; Liu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Liang, Y.; Shi, J.; et al. Revealing the Sources of Cadmium in Rice Plants under Pot and Field Conditions from Its Isotopic Fractionation. Acs Environ. Au 2024, 4, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.J.; Ma, Y.; Zhu, Y.G.; Tang, Z.; McGrath, S.P. Soil Contamination in China: Current Status and Mitigation Strategies. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 750–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Chen, H.; Kopittke, P.M.; Zhao, F.-J. Cadmium contamination in agricultural soils of China and the impact on food safety. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 249, 1038–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, D.; Wu, J.; Xie, Y.; Xie, J.; Huang, X.; Ji, X. Double Prevention of Cadmium Uptake by Iron and Zinc in Rice Seedling-A Hypotonic Study. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 24, 318–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Deng, K.; Shi, Y.; Liu, S.; Jian, Z.; Li, C.; Ji, X.; Li, S. Alleviation of Cd-polluted paddy soils through Si fertilizer application and its effects on the soil microbial community. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 855, 158735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.Y.; Zhao, F.J.; Wang, P. The relative contributions of root uptake and remobilization to the loading of Cd and As into rice grains: Implications in simultaneously controlling grain Cd and As accumulation using a segmented water management strategy. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 293, 118497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.; Ghouri, F.; Zhong, M.; Bukhari, S.A.H.; Ali, S.; Shahid, M.Q. Rice and heavy metals: A review of cadmium impact and potential remediation techniques. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 957, 177403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozyigit, I.I.; Can, H.; Dogan, I. Phytoremediation using genetically engineered plants to remove metals: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 669–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake-Mahmud, J.; Sessa, E.B.; Visger, C.J.; Watkins, J.E., Jr. Polyploidy and environmental stress response: A comparative study of fern gametophytes. New Phytol. 2025, 245, 885–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, T.; Zhou, H.; Gu, J.; Jia, R.; Li, H.; Wang, Q.; Zeng, M.; Liao, B. Cadmium accumulation and bioavailability in paddy soil under different water regimes for different growth stages of rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Soil 2019, 440, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Mao, B.; Li, Y.; Lv, Q.; Zhang, L.; Chen, C.; He, H.; Wang, W.; Zeng, X.; Shao, Y.; et al. Knockout of OsNramp5 using the CRISPR/Cas9 system produces low Cd-accumulating indica rice without compromising yield. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 14438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, X.; Liang, R.; Wang, G.; Ma, S.; Liu, N.; Gong, Y.; McCouch, S.R.; Zhu, H.; Liu, Z.; Li, Z.; et al. Design of rice with low cadmium accumulation in grain using single segment substitution line. New Crops 2025, 2, 100035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchimiya, M.; Bannon, D.; Nakanishi, H.; McBride, M.B.; Williams, M.A.; Yoshihara, T. Chemical Speciation, Plant Uptake, and Toxicity of Heavy Metals in Agricultural Soils. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 12856–12869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Huang, X.; Lu, L. Mitigating cadmium contamination in rice: Insights from a large-scale meta-analysis of amendment effects. Plant Soil 2024, 505, 493–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessier, A.; Campbell, P.G.C.; Bisson, M. Trace metal speciation in the Yamaska and St. François Rivers (Quebec). Can. J. Earth Sci. 1980, 17, 90–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arinzechi, C.; Huang, P.; Ping, Y.; Xu, H.; Wang, Q.; Tang, C.; Si, M.; Li, Q.; Yang, Z. Calcium-magnesium synergy in reducing cadmium bioavailability and uptake in rice plants. Int. J. Phytoremediation 2025, 27, 832–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Mock, H.P.; Giehl, R.F.H.; Pitann, B.; Mühling, K.H. Silicon decreases cadmium concentrations by modulating root endodermal suberin development in wheat plants. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 364, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Chen, J.; Hu, Y.; You, Y.; Sun, X.; Yu, J.; Guo, X.; Hu, C.; Chen, C.; Chen, Y.; et al. Influence of FeSO4, nano zero-valent iron, and their CaCO3 composites on the formation of iron plaque and cadmium translocation in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Environ. Pollut. Bioavailab. 2024, 36, 2368588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Peng, H.; Xie, Y.; Wang, X.; Huang, R.; Chen, H.; Ji, X. The role of silicon in cadmium alleviation by rice root cell wall retention and vacuole compartmentalization under different durations of Cd exposure. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 226, 112810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Y.; Peng, L.; Tam, N.F.y.; Lin, Q.; Liang, H.; Li, W.C.; Ye, Z. Effects of fly ash and steel slag on cadmium and arsenic accumulation in rice grains and soil health: A field study over four crop seasons in Guangdong, China. Geoderma 2022, 419, 11587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Fu, P.; Ni, W.; Zhang, S.; Li, S.; Deng, W.; Hu, W.; Li, J.; Pei, F.; Du, L.; et al. A review of solid wastes-based stabilizers for remediating heavy metals co-contaminated soil: Applications and challenges. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 920, 170667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, M.Z.u.; Rizwan, M.; Rauf, A.; Ayub, M.A.; Ali, S.; Qayyum, M.F.; Waris, A.A.; Naeem, A.; Sanaullah, M. Split application of silicon in cadmium (Cd) spiked alkaline soil plays a vital role in decreasing Cd accumulation in rice (Oryza sativa L.) grains. Chemosphere 2019, 226, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, D.; Ji, X.; Liu, S.; Chen, S.; Xie, Y.; Wu, J. Exploration of the bio-availability and the risk thresholds of cadmium and arsenic in contaminated paddy soils. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HJ 649-2013; Soil—Determination of Exchangeable Acidity Using Potassium Chloride Extraction—Titration Method. The Ministry of Environmental Protection of China: Beijing, China, 2013.

- NY/T 1121.15-2006; Soil Testing. Part 15: Method for Determination of Soil Available Silicon. The Ministry of Agriculture of China: Beijing, China, 2006.

- Guan, D.; Wu, J.; Sun, S.; Ji, X.; Huang, X.; Liu, S.; Xie, Y. Iron and zinc-mediated regulation of cadmium transport in the rice (Oryza sativa L.) stem-leaf-grain pathway. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 307, 119430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Ning, Y.; Ji, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, H.; Ma, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J. Biochar and Manure Co-Application Increases Rice Yield in Low Productive Acid Soil by Increasing Soil pH, Organic Carbon, and Nutrient Retention and Availability. Plants 2024, 13, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Na, M.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, J.; Li, L.-J. Changes in microbial carbon cycling functions along rice cultivation chronosequences in saline-alkali soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2025, 202, 109699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, M.; Guo, L.; Yang, D.; He, N.; Ying, B.; Wang, Y. Influence of silicon on cadmium availability and cadmium uptake by rice in acid and alkaline paddy soils. J. Soils Sediments 2020, 20, 2343–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, F.; Dong, Z.; Lamb, D.; Naidu, R.; Bolan, N.S.; Ok, Y.S.; Liu, C.; Khan, N.; Johir, M.A.H.; Semple, K.T. Effects of acidic and neutral biochars on properties and cadmium retention of soils. Chemosphere 2017, 180, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhan, L.; Li, Z.; Tang, Q. Adsorption behavior and mechanism of Cd (II) on loess soil from China. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 172, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.; Bishnoi, N.R.; Kirrolia, A. Evaluation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa an innovative bioremediation tool in multi metals ions from simulated system using multi response methodology. Bioresour Technol 2013, 138, 222–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Liu, J.; You, Z.; Huang, P.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, C. Plasma membrane-associated calcium signaling modulates cadmium transport. New Phytol 2023, 238, 313–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X.; Zhang, C.; Wang, H.; Zhang, F. Effect of Si on the distribution of Cd in rice seedlings. Plant Soil 2005, 272, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, Q.; Xiao, A.; Li, C.; Li, Y. Regulation of soil properties by amendments and their impact on Cd fractions and bacterial community structure: Exploring the mechanism of inhibition on Cd phytoavailability. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 294, 118033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L.; Huang, N.; Liu, X.; Gong, L.; Xu, M.; Zhang, S.; Chen, C.; Wu, J.; Yang, G. Enhanced silicate remediation in cadmium-contaminated alkaline soil: Amorphous structure improves adsorption performance. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 326, 116760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.d.C.; Ganga, A.; Cattanio, I.S.; Martins, A.R.; Alves, R.S.; Lessa, L.G.F.; Pereira, H.S.; Galindo, F.S.; Teixeira Filho, M.C.M.; Abreu-Junior, C.H.; et al. Residual Effect of Silicate Agromineral Application on Soil Acidity, Mineral Availability, and Soybean Anatomy. Agronomy 2025, 15, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhou, D.; Hang, H.; Chen, S.; Liu, H.; Su, J.; Lv, H.; Jia, H.; Zhao, G. Effects of Balancing Exchangeable Cations Ca, Mg, and K on the Growth of Tomato Seedlings (Solanum lycopersicum L.) Based on Increased Soil Cation Exchange Capacity. Agronomy 2024, 14, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.F.; Yamaji, N. Silicon uptake and accumulation in higher plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2006, 11, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beygi, M.; Jalali, M. Assessment of trace elements (Cd, Cu, Ni, Zn) fractionation and bioavailability in vineyard soils from the Hamedan, Iran. Geoderma 2019, 337, 1009–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Gao, J.; Yue, T.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Bai, J. Distribution, chemical fractionation, and potential environmental risks of Hg, Cr, Cd, Pb, and As in wastes from ultra-low emission coal-fired industrial boilers in China. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 446, 130606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Y.; Li, J.; Zeng, X.; Zhang, N.; Wen, J.; Liu, J.; Jiku, M.A.S.; Wu, C.; Su, S. The performance and mechanism of cadmium availability mitigation by biochars differ among soils with different pH: Hints for the reasonable choice of passivators. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 312, 114903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Liu, T.; Li, X.; Yin, M.; Yin, H.; Tong, H.; Huang, F.; Li, F. Cd isotope fractionation in a soil-rice system: Roles of pH and mineral transformation during Cd immobilization and migration processes. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 900, 166435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.y.; Liu, Z.d.; Li, Y.; Jiang, T.; Xu, M.; Li, J.y.; Xu, R.k. Mechanisms for increasing soil resistance to acidification by long-term manure application. Soil Tillage Res. 2019, 185, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulikowska, D.; Gusiatin, Z.M.; Bułkowska, K.; Klik, B. Feasibility of using humic substances from compost to remove heavy metals (Cd, Cu, Ni, Pb, Zn) from contaminated soil aged for different periods of time. J. Hazard. Mater. 2015, 300, 882–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, D.; Wu, J.; Xie, Y.; Chen, S.; Chen, J.; Peng, H.; Ji, X. Effects of Iron-based silicon salts on fractions and transformation of cadmium and arsenic in soil environment. China Environ. Sci. 2022, 42, 1803–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Yueyang Area (XY) | Yiyang Area (HS) |

|---|---|---|

| Soil type | river drift soil | |

| Terrain | open and gently rolling | lake area and hills alternate |

| pH value | 5.4 ± 0.007 | 4.7 ± 0.005 |

| Hydrolyzable nitrogen (mg/kg) | 155 ± 1.42 | 185 ± 2.24 |

| Olsen-P (mg/kg) | 6.2 ± 0.21 | 2.8 ± 0.14 |

| Olsen-K (mg/kg) | 139 ± 1.47 | 145 ± 1.12 |

| Available Si (mg/kg) | 124 ± 0.87 | 115 ± 0.62 |

| Base saturation (%) | 42.6 ± 0.74 | 72.2 ± 0.96 |

| Cd (mg/kg) | 0.554 ± 0.013 | 0.471 ± 0.024 |

| Available Cd (mg/kg) | 0.330 ± 0.018 | 0.281 ± 0.027 |

| Parameters | Factor | Measurement Value |

|---|---|---|

| Elemental composition % (active forms) | CaO | 53.6 ± 0.54 |

| SiO2 | 10.9 ± 0.32 | |

| MgO | 4.33 ± 0.23 | |

| Fe2O3 | 0.23 ± 0.04 | |

| pH | / | 12.1 ± 0.0 |

| Particle size (<1.00 mm) % | / | 99 ± 0.0 |

| Heavy metal background (mg/kg) | Hg | not detected |

| As | 5.0 ± 0.19 | |

| Cd | 0.1 ± 0.009 | |

| Pb | 2.1 ± 0.08 | |

| Cr | 17.5 ± 0.22 |

| Year | Treatments | DTPA-Cd (mg/kg) | EX-Cd (mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | HSCK | 0.351 ± 0.0058 a | 0.185 ± 0.00426 a |

| HSCSM1 | 0.333 ± 0.0115 ab | 0.183 ± 0.00615 a | |

| HSCSM2 | 0.316 ± 0.00964 b | 0.168 ± 0.00719 b | |

| XYCK | 0.365 ± 0.0124 a | 0.200 ± 0.0154 a | |

| XYCSM1 | 0.294 ± 0.0130 b | 0.188 ± 0.00442 a | |

| XYCSM2 | 0.264 ± 0.0219 b | 0.188 ± 0.0160 a | |

| 2023 | HSCK | 0.267 ± 0.0118 a | 0.189 ± 0.00883 a |

| HSCSM1 | 0.260 ± 0.00215 a | 0.195 ± 0.0180 a | |

| HSCSM2 | 0.250 ± 0.0122 a | 0.187 ± 0.0167 a | |

| XYCK | 0.362 ± 0.0214 a | 0.167 ± 0.00875 a | |

| XYCSM1 | 0.351 ± 0.0179 a | 0.149 ± 0.00165 ab | |

| XYCSM2 | 0.329 ± 0.0303 b | 0.138 ± 0.00246 b |

| Year | Treatments | EXC-Al | EXC-Ca | EXC-Mg | EXC-K | EXC-Na |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (cmol/kg) | ||||||

| 2021 | HS-CK | 3.02 ± 0.0866 a | 4.57 ± 0.149 c | 0.853 ± 0.0154 c | 0.215 ± 0.0092 a | 0.132 ± 0.00476 a |

| HS-CSM1 | 1.75 ± 0.130 b | 6.60 ± 0.266 b | 1.13 ± 0.0523 b | 0.193 ± 0.00972 a | 0.143 ± 0.0118 a | |

| HS-CSM2 | 0.853 ± 0.108 c | 7.97 ± 0.244 a | 1.40 ± 0.0628 a | 0.223 ± 0.00924 a | 0.141 ± 0.0100 a | |

| XY-CK | 0.46 ± 0.0602 a | 5.75 ± 0.288 b | 0.796 ± 0.0111 c | 0.394 ± 0.0124 a | 0.343 ± 0.0581 a | |

| XY-CSM1 | 0.24 ± 0.0513 b | 6.43 ± 0.0636 b | 0.978 ± 0.0373 b | 0.394 ± 0.0198 a | 0.298 ± 0.0538 a | |

| XY-CSM2 | 0.09 ± 0.0099 c | 8.17 ± 0.465 a | 1.196 ± 0.0621 a | 0.388 ± 0.0263 a | 0.349 ± 0.0456 a | |

| 2022 | HS-CK | 2.63 ± 0.400 a | 4.12 ± 0.196 b | 1.06 ± 0.0764 b | 0.304 ± 0.00535 a | 0.112 ± 0.0159 a |

| HS-CSM1 | 0.750 ± 0.150 b | 6.40 ± 0.501 a | 1.54 ± 0.0268 a | 0.304 ± 0.0308 a | 0.158 ± 0.00919 a | |

| HS-CSM2 | 0.541 ± 0.0295 c | 7.04 ± 0.587 a | 1.76 ± 0.110 a | 0.341 ± 0.0335 a | 0.121 ± 0.0243 a | |

| XY-CK | 0.291 ± 0.0434 a | 6.08 ± 0.254 b | 1.39 ± 0.0868 b | 0.306 ± 0.0291 a | 0.152 ± 0.0180 a | |

| XY-CSM1 | 0.124 ± 0.0065 b | 7.32 ± 0.194 a | 1.76 ± 0.0339 a | 0.282 ± 0.0115 a | 0.134 ± 0.0155 a | |

| XY-CSM2 | 0.157 ± 0.0300 b | 7.79 ± 0.495 a | 1.83 ± 0.0952 a | 0.293 ± 0.0321 a | 0.115 ± 0.0090 a | |

| 2023 | HS-CK | 2.50 ± 0.0720 a | 3.26 ± 0.146 c | 1.14 ± 0.0174 b | 0.318 ± 0.0139 a | 0.0944 ± 0.00910 a |

| HS-CSM1 | 0.516 ± 0.0509 b | 6.65 ± 0.0779 b | 1.56 ± 0.00511 a | 0.307 ± 0.0328 a | 0.0839 ± 0.00525 a | |

| HS-CSM2 | 0.128 ± 0.0140 c | 9.02 ± 0.236 a | 1.83 ± 0.0950 a | 0.328 ± 0.0345 a | 0.0839 ± 0.00695 a | |

| XY-CK | 0.562 ± 0.0894 a | 4.83 ± 0.344 b | 1.06 ± 0.0275 b | 0.435 ± 0.0321 a | 0.236 ± 0.00 a | |

| XY-CSM1 | 0.100 ± 0.00855 b | 7.40 ± 0.299 ab | 1.26 ± 0.0293 a | 0.440 ± 0.0399 a | 0.236 ± 0.0252 a | |

| XY-CSM2 | 0.0161 ± 0.0126 c | 9.31 ± 1.27 a | 1.42 ± 0.0838 a | 0.387 ± 0.00528 a | 0.196 ± 0.00907 a | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, S.; Guan, D.; Xie, Y.; Tian, F.; Ji, X.; Wu, J. Calcium–Silicon–Magnesium Synergistic Amendment Enhances Cadmium Mitigation in Oryza sativa L. via Soil Immobilization and Nutrient Regulation Dynamics. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2580. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242580

Sun S, Guan D, Xie Y, Tian F, Ji X, Wu J. Calcium–Silicon–Magnesium Synergistic Amendment Enhances Cadmium Mitigation in Oryza sativa L. via Soil Immobilization and Nutrient Regulation Dynamics. Agriculture. 2025; 15(24):2580. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242580

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Shaohui, Di Guan, Yunhe Xie, Faxiang Tian, Xionghui Ji, and Jiamei Wu. 2025. "Calcium–Silicon–Magnesium Synergistic Amendment Enhances Cadmium Mitigation in Oryza sativa L. via Soil Immobilization and Nutrient Regulation Dynamics" Agriculture 15, no. 24: 2580. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242580

APA StyleSun, S., Guan, D., Xie, Y., Tian, F., Ji, X., & Wu, J. (2025). Calcium–Silicon–Magnesium Synergistic Amendment Enhances Cadmium Mitigation in Oryza sativa L. via Soil Immobilization and Nutrient Regulation Dynamics. Agriculture, 15(24), 2580. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242580