Affordable 3D Technologies for Contactless Cattle Morphometry: A Comparative Pilot Trial of Smartphone-Based LiDAR, Photogrammetry and Neural Surface Reconstruction Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

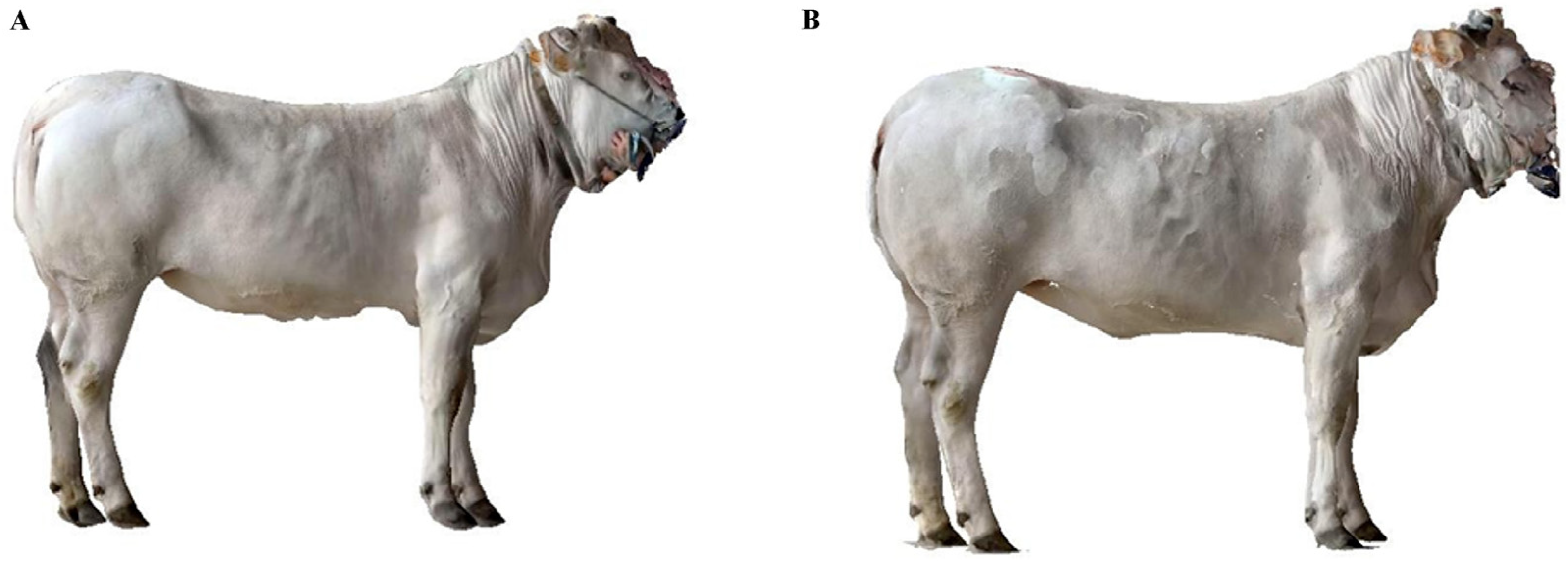

2.1. Location and Animals’ Descriptions

2.2. Morphometric Measurements

- Body Length (BL): distance from the shoulder tip—scapulohumeral joint—to the tip of the ischial tuberosity—the back of the croup.

- Chest Height (CH): vertical distance from the highest to lowest point of the chest.

- Chest Width (CW): frontal distance between the outermost points of the chest.

- Rump Length (RL): distance from the coxal tuberosity—the tip of the hip—to the ischial tuberosity—the tip of the ilium/buttocks.

- Wither Height (WH): vertical distance from the ground to the highest point of the wither.

2.3. Digital Tools’ Technical Specifications

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Manual Acquisition of Animals’ Morphometric Measurements Using Conventional Procedure

2.6. Digital Acquisition of Animals’ Shape Using Smartphone’s Camera and Sensors

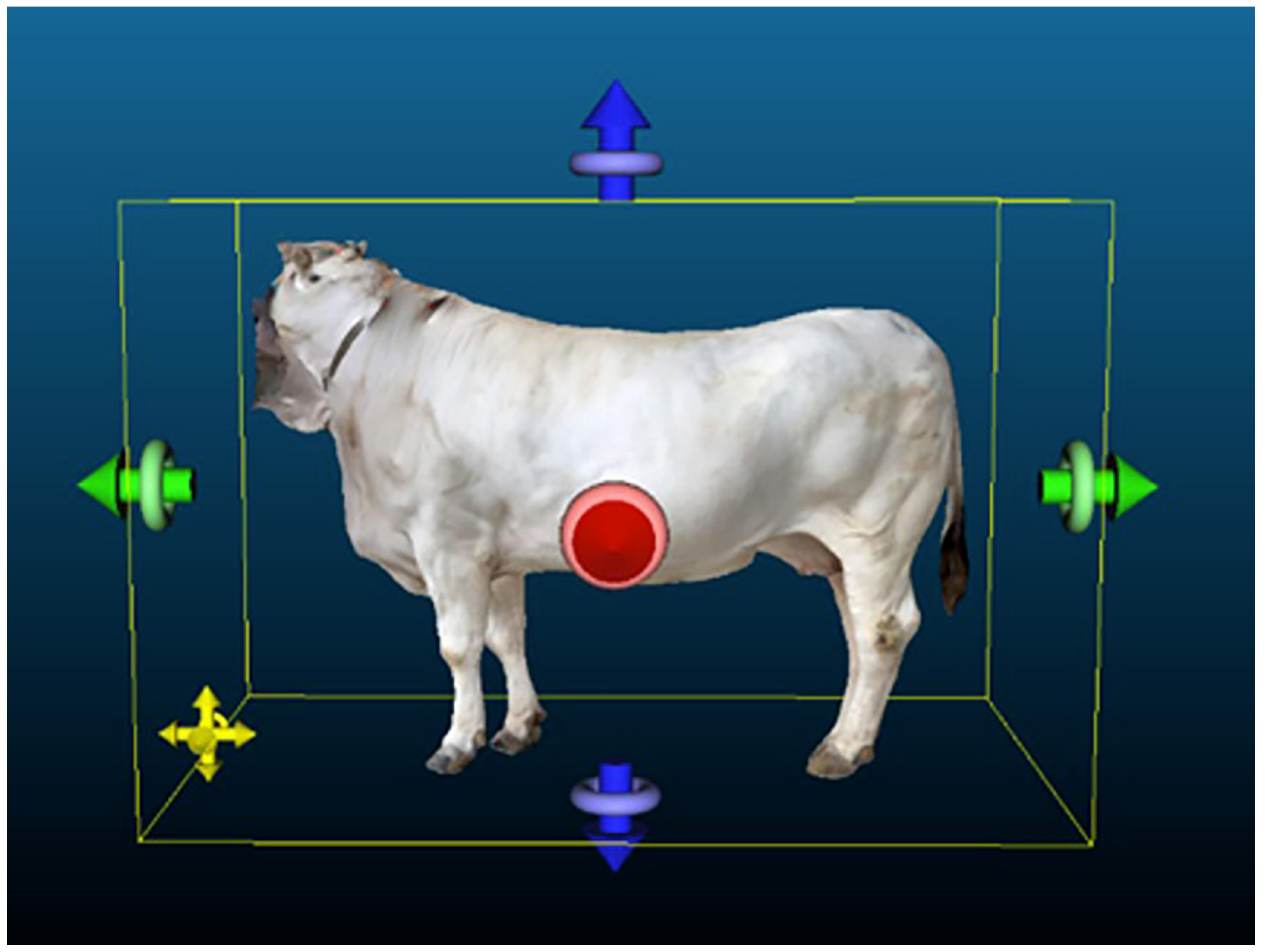

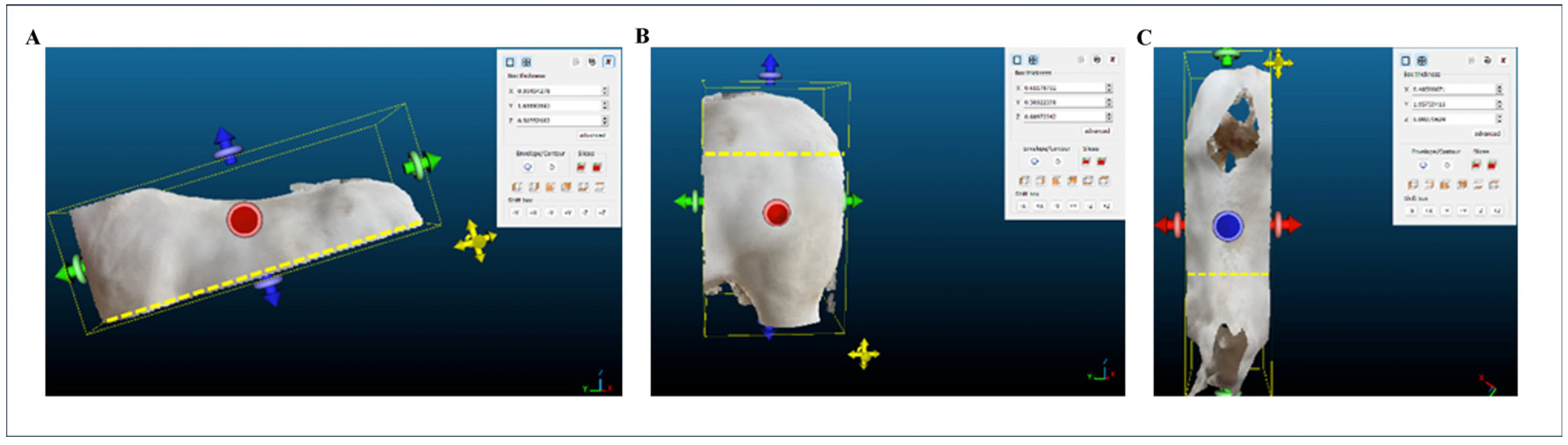

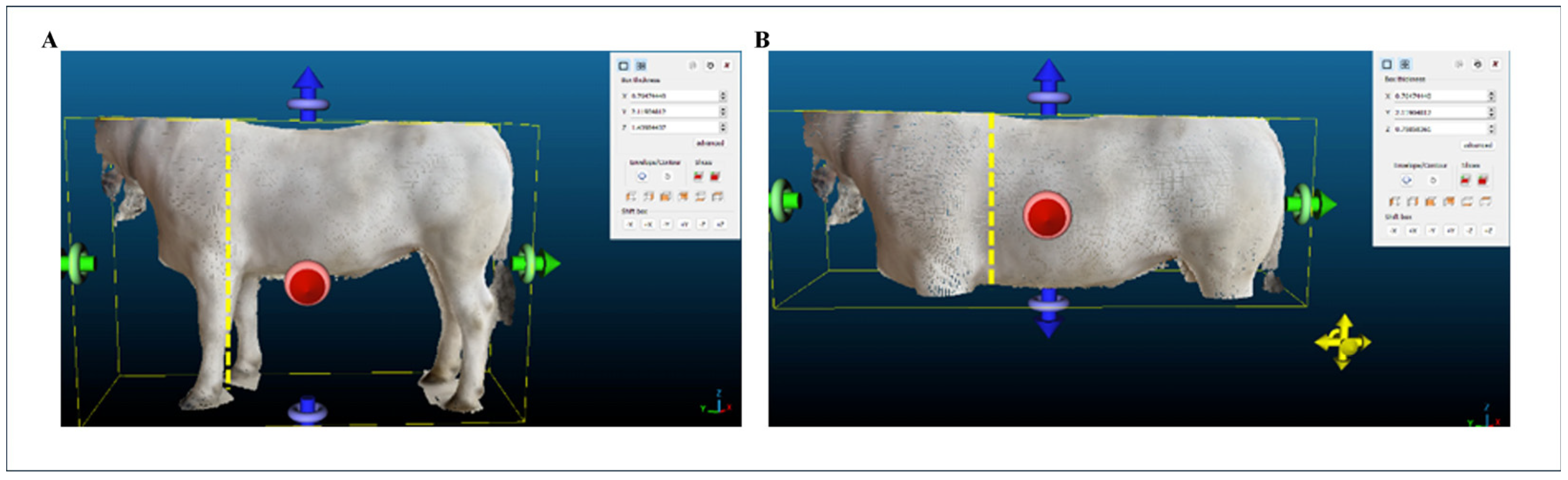

2.7. Processing of 3D Point Clouds and Meshes of the Animals

2.7.1. Model Scaling

2.7.2. Model Filtering

2.8. Extraction of Morphometric Measurements from the 3D Point Clouds and Meshes of the Animals

2.9. Evaluation of the Accuracy of the Digital Approach

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Practical Feasibility of Handheld Technology Under Field Conditions

4.2. Accuracy and Reliability of Handheld Approach for Biological Data Acquisition

4.2.1. Technological Sources of Variability

4.2.2. Biological Sources of Variability

4.3. User-Dependent Sources of Error

5. Challenges and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3D | Three Dimensional |

| 3DGS | Three-Dimensional Gaussian Splatting |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AKIS | Agricultural Knowledge and Innovation System |

| ANABIC | National Association of Italian Beef Cattle Breeders |

| BL | Body Length |

| CH | Chest Height |

| CW | Chest Width |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| LiDAR | Light Detection and Ranging |

| NeRF | Neural Radiance Fields |

| NSR | Neural Surface Reconstruction |

| PLF | Precision Livestock Farming |

| PLS | Personal Laser Scanning |

| RGB | Red, Green, Blue |

| RL | Rump Length |

| SCAR | Standing Committee on Agricultural Research |

| WH | Wither Height |

References

- Terry, S.A.; Basarab, J.A.; Guan, L.L.; McAllister, T.A. Strategies to improve the efficiency of beef cattle production. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 101, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henchion, M.; Hayes, M.; Mullen, A.M.; Fenelon, M.; Tiwari, B. Future protein supply and demand: Strategies and factors influencing a sustainable equilibrium. Foods 2017, 6, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neethirajan, S. The role of sensors, big data and machine learning in modern animal farming. Sens. Bio-Sens. Res. 2020, 29, 100367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, J.R.; Arroqui, M.; Mangudo, P.; Toloza, J.; Jatip, D.; Rodríguez, J.M.; Teyseyre, A.; Sanz, C.; Zunino, A.; Machado, C. Body condition estimation on cows from depth images using Convolutional Neural Networks. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 155, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Speech by President von der Leyen at the European Agri-Food Days via Video Message. 2024. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/speech_24_6323 (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Kountios, G.; Kanakaris, S.; Moulogianni, C.; Bournaris, T. Strengthening AKIS for Sustainable Agricultural Features: Insights and Innovations from the European Union: A Literature Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Fostering an Effective and Integrated AKIS in Member States. 2024. Available online: https://eu-cap-network.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/publications/2024-12/eu-cap-network-event-report-seminar-akis.pdf (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- European Commission. EU Agri-Food Days 2024. 2024. Available online: https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/overview-vision-agriculture-food/digitalisation_en (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Colombi, D.; Rovelli, G.; Luigi-Sierra, M.G.; Ceccobelli, S.; Guan, D.; Perini, F.; Sbarra, F.; Quaglia, A.; Sarti, F.M.; Pasquini, M.; et al. Population structure and identification of genomic regions associated with productive traits in five Italian beef cattle breeds. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 8529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANABIC. Associazione Nazionale Allevatori Bovini Italiani da Carne. Available online: https://www.anabic.it (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Kenny, D.A.; Fitzsimons, C.; Waters, S.M.; McGee, M. Invited review: Improving feed efficiency of beef cattle—The current state of the art and future challenges. Animal 2018, 12, 1815–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dingwell, R.T.; Wallace, M.M.; McLaren, C.J.; Leslie, C.F.; Leslie, K.E. An evaluation of two indirect methods of estimating body weight in Holstein calves and heifers. J. Dairy Sci. 2006, 89, 3992–3998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouédraogo, D.; Soudré, A.; Ouédraogo-Koné, S.; Zoma, B.L.; Yougbaré, B.; Khayatzadeh, N.; Burger, P.A.; Mészáros, G.; Traoré, A.; Mwai, O.A.; et al. Breeding objectives and practices in three local cattle breed production systems in Burkina Faso with implication for the design of breeding programs. Livest. Sci. 2020, 232, 103910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehtiö, T.; Pitkänen, T.; Leino, A.M.; Mäntysaari, E.A.; Kempe, R.; Negussie, E.; Lidauer, M.H. Genetic analyses of metabolic body weight, carcass weight and body conformation traits in Nordic dairy cattle. Animal 2021, 15, 100398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petherick, J.C.; Doogan, V.J.; Venus, B.K.; Holroyd, R.G.; Olsson, P. Quality of handling and holding yard environment, and beef cattle temperament: 2, Consequences for stress and productivity. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2009, 120, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Cao, S.; Li, S.; Bai, T.; Zhao, Z.; Sun, W. Automated measurement of cattle dimensions using improved keypoint detection combined with unilateral depth imaging. Animals 2024, 14, 2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudioso, V.; Sanz-Ablanedo, E.; Lomillos, J.M.; Alonso, M.E.; Javares-Morillo, L.; Rodríguez, P. “Photozoometer”: A new photogrammetric system for obtaining morphometric measurements of elusive animals. Livest. Sci. 2014, 165, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cominotte, A.; Fernandes, A.F.A.; Dorea, J.R.R.; Rosa, G.J.M.; Ladeira, M.M.; Van Cleef, E.; Pereira, G.L.; Baldassini, W.A.; Neto, O.R.M. Automated computer vision system to predict body weight and average daily gain in beef cattle during growing and finishing phases. Livest. Sci. 2020, 232, 103904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imaz, J.A.; Garcia, S.; González, L.A. Using automated in-paddock weighing to evaluate the impact of intervals between liveweight measures on growth rate calculations in grazing beef cattle. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 178, 105729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Kong, H.; Clark, C.; Lomax, S.; Su, D.; Eiffert, S.; Sukkarieh, S. Intelligent perception for cattle monitoring: A review for cattle identification, body condition score evaluation, and weight estimation. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 185, 106143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapar, G.; Biswas, T.K.; Bhushan, B.; Naskar, S.; Kumar, A.; Dandapat, P.; Rokhade, J. Accurate estimation of body weight of pigs through smartphone image measurement app. Smart Agric. Technol. 2023, 4, 100194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Li, S.; Zhu, A.; Fan, X.; Zhang, C.; Wang, H. Non-contact body measurement for qinchuan cattle with LiDAR sensor. Sensors 2018, 18, 3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Guo, H.; Rao, Q.; Hou, Z.; Li, S.; Qiu, S.; Fan, X.; Wang, H. Body dimension measurements of qinchuan cattle with transfer learning from liDAR sensing. Sensors 2019, 19, 5046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Cozler, Y.; Allain, C.; Caillot, A.; Delouard, J.M.; Delattre, L.; Luginbuhl, T.; Faverdin, P. High-precision scanning system for complete 3D cow body shape imaging and analysis of morphological traits. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 157, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilchuen, P.; Yaigate, T.; Sumon, W. Body measurements of beef cows by using mobile phone application and prediction of body weight with regression model. Songklanakarin J. Sci. Technol. 2021, 43, 1635–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ma, W.; Li, Q.; Zhao, C.; Tulpan, D.; Yang, S.; Ding, L.; Gao, R.; Yu, L.; Wang, Z. Multi-view real-time acquisition and 3D reconstruction of point clouds for beef cattle. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 197, 106987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Lu, H.; Wu, J.; Lei, J.; Zhang, J.; Luo, X.; Guo, H. Rapid and Automated Body Measurement of Cattle Based on Statistical Shape Model. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 2023, 10, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Zhang, J.; Yuan, X.; Lv, J.; Zeng, Z.; Guo, H.; Ruchay, A. Automatic coarse-to-fine method for cattle body measurement based on improved GCN and 3D parametric model. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 231, 110017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukun, S.; Pengju, H.; Yujie, W.; Ziqi, C.; Yang, L.; Baisheng, D.; Runze, L.; Yonggen, Z. Automatic monitoring system for individual dairy cows based on a deep learning framework that provides identification via body parts and estimation of body condition score. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 10140–10151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, K.; Zhang, M.; Shen, W.; Liu, X.; Ji, J.; Dai, B.; Zhang, R. Automatic body condition scoring for dairy cows based on efficient net and convex hull features of point clouds. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 205, 107588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Xu, X.; Song, L.; Zhang, Q.; Duan, Y.; Song, H. Automated measurement of dairy cows body size via 3D point cloud data analysis. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 200, 107218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Huang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Miao, Y. Body weight estimation of beef cattle with 3D deep learning model: PointNet++. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 213, 108184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerbl, B.; Kopanas, G.; Leimkühler, T.; Drettakis, G. 3D Gaussian Splatting for Real-Time Radiance Field Rendering. ACM Trans. Graph. 2023, 42, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mildenhall, B.; Srinivasan, P.P.; Tancik, M.; Barron, J.T.; Ramamoorthi, R.; Ng, R. Nerf: Representing scenes as neural radiance fields for view synthesis. Commun. ACM 2021, 65, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilchuen, P.; Suwanasopee, T.; Koonawootrittriron, S. Integrating deep learning and mobile imaging for assessment of automated conformational indices and weight prediction in Brahman cattle. Smart Agr. Technol. 2025, 12, 101079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Hu, Y.; Gao, Z.; Guo, H.; Su, Y. Automated measurement of livestock body based on pose normalisation using statistical shape model. Biosyst. Eng. 2023, 227, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Guo, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, C. A Lightweight Automatic Cattle Body Measurement Method Based on Keypoint Detection. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recon-3d. 2023. Available online: https://www.recon-3d.com (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- KIRI Engine. 2023. Available online: https://www.kiriengine.com (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Luma AI Inc. 2023. Available online: https://www.lumalabs.ai (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Jing, X.; Wu, T.; Shen, P.; Chen, Z.; Jia, H.; Song, H. In situ volume measurement of dairy cattle via neural radiance fields-based 3D reconstruction. Biosyst. Eng. 2025, 250, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, C.E.; Liscio, E. Validation of Recon-3D, iPhone LiDAR for bullet trajectory documentation. Forensic Sci. Int. 2023, 350, 111787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavani, S.; Billi, A.; Corradetti, A.; Mercuri, M.; Bosman, A.; Cuffaro, M.; Seers, T.; Carminati, E. Smartphone assisted fieldwork: Towards the digital transition of geoscience fieldwork using LiDAR-equipped iPhones. Earth Sci. Rev. 2022, 227, 103969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottner, S.; Thali, M.J.; Gascho, D. Using the iPhone’s LiDAR technology to capture 3D forensic data at crime and crash scenes. Forensic Imag. 2023, 32, 200535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Liu, L.; Liu, Y.; Theobalt, C.; Komura, T.; Wang, W. Neus: Learning neural implicit surfaces by volume rendering for multi-view reconstruction. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 27171–27183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Xu, Z.; Philip, J.; Bi, S.; Shu, Z.; Sunkavalli, K.; Neumann, U. Point-nerf: Point-based neural radiance fields. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 21–24 June 2022; pp. 5438–5448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiappini, S.; Marcheggiani, E.; Pierdicca, R.; Choudhury, M.A. Assessment of 3D Models of Rural Buildings Using UAV Images: A Comparison of NeRF, GS and MVS-SFM Methods. In Proceedings of the Biosystems Engineering Promoting Resilience to Climate Change-AIIA 2024-Mid-Term Conference, Padova, Italy, 17–19 June 2024; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 1190–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, K.; Zhang, W.; Xiao, C. MegaSurf: Scalable Large Scene Neural Surface Reconstruction. In Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Melbourne, Australia, 28 October–1 November 2024; pp. 6414–6423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Xu, Q.; Ong, Y.S.; Tao, W. Geo-neus: Geometry-consistent neural implicit surfaces learning for multi-view reconstruction. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 3403–3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, Y.; Yaguchi, Y. RapidSim: Enhancing Robotic Simulation with Photorealistic 3D Environments via Smartphone-Captured NeRF and UE5 Integration. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Image Processing and Robotics (ICIPRoB), Colombo, Sri Lanka, 9–10 March 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stefano, F.; Chiappini, S.; Gorreja, A.; Balestra, M.; Pierdicca, R. Mobile 3D scan LiDAR: A literature review. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2021, 12, 2387–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saif, W.; Alshibani, A. Smartphone-Based Photogrammetry Assessment in Comparison with a Compact Camera for Construction Management Applications. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CloudCompare. CloudCompare V2.13.1. 2024. Available online: https://www.cloudcompare.org/release/notes/20240320/ (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Pérez-Ruiz, M.; Tarrat-Martín, D.; Sánchez-Guerrero, M.J.; Valera, M. Advances in horse morphometric measurements using LiDAR. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 174, 105510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Studio. R Studio v 2025.09.1+401. 2025. Available online: https://dailies.rstudio.com/version/2025.09.1+401 (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Dang, C.G.; Lee, S.S.; Alam, M.; Lee, S.M.; Park, M.N.; Seong, H.S.; Han, S.; Nguyen, H.P.; Baek, M.K.; Lee, J.G.; et al. Korean Cattle 3D Reconstruction from Multi-View 3D-Camera System in Real Environment. Sensors 2024, 24, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Summerfield, G.I.; De Freitas, A.; van Marle-Koster, E.; Myburgh, H.C. Automated cow body condition scoring using multiple 3D cameras and convolutional neural networks. Sensors 2023, 23, 9051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, Y.; Condotta, I.C.; Musgrave, J.A.; Brown-Brandl, T.M.; Mulliniks, J.T. Estimating body weight and body condition score of mature beef cows using depth images. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2023, 7, txad085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, Q.; Ma, W.; Li, M.; Torre, A.D.L.; Yang, S.X.; Zhao, C. A Multi-View Real-Time Approach for Rapid Point Cloud Acquisition and Reconstruction in Goats. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruchay, A.; Kober, V.; Dorofeev, K.; Kolpakov, V.; Miroshnikov, S. Accurate body measurement of live cattle using three depth cameras and non-rigid 3-D shape recovery. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 179, 105821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Recio, O.; Rosa, G.J.M.; Gianola, D. Machine learning methods and predictive ability metrics for genome-wide prediction of complex traits. Livest. Sci. 2014, 166, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Bokkers, E.A.M.; van der Tol, P.P.J.; Koerkamp, P.W.G.G.; van Mourik, S. Automated body weight prediction of dairy cows using 3-dimensional vision. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 4448–4459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, D.H.; Kim, C.; Ko, Y.G.; Kim, H.Y. Estimation of body weight for Korean cattle using three-dimensional image. J. Biosyst. Eng. 2020, 45, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, V.A.M.; de Lima, W.F.; da Silva, O.A.; Astolfi, G.; Menezes, G.V.; de Andrade Porto, J.V.; Rezende, F.P.C.; Moraes, P.H.; Matsubara, E.T.; Mateus, R.; et al. Cattle weight estimation using active contour models and regression trees Bagging. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 179, 105804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, R.F. Beyond traditional time-series: Using demand sensing to improve forecasts in volatile times. J. Bus. Forecast. 2012, 31, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Kim, H. A new metric of absolute percentage error for intermittent demand forecasts. Int. J. Forecast. 2016, 32, 669–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuura, A.; Torii, S.; Ojima, Y.; Kiku, Y. 3D imaging and body measurement of riding horses using four scanners simultaneously. J. Equine Sci. 2024, 35, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, A.; Luginbuhl, T.; Delattre, L.; Delouard, J.M.; Faverdin, P. Rear shape in 3 dimensions summarized by principal component analysis is a good predictor of body condition score in Holstein dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 4465–4476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Name | License | Price | Point Cloud | Mesh | File Format | Version |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recon-3D | Free/By charge | 75 $/month | Yes | Yes | E57; and others | 1.9 |

| KIRI Engine | Free/By charge | 6.66 $/month | No | Yes | .las; .obj; and others | 3.13 |

| Luma AI | Free/By charge | 7.99 $/month | Yes | No | .ply; and others | 1.0 |

| Cow | Application | Reconstruction Technique | Data Type | Raw Number of Points | Number of Points After Registration and Cleaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Recon-3D | LiDAR | Point cloud | 607,797 | 48,663 |

| Recon-3D | Photogrammetry | Point cloud | 895,267 | 104,681 | |

| KIRI Engine | NSR | Mesh | 52,800 | 52,800 | |

| KIRI Engine | 3DGS | Mesh | 505,455 | 119,712 | |

| Luma AI | NeRF | Point cloud | 2,085,075 | 507,570 | |

| 2 | Recon-3D | LiDAR | Point cloud | 224,671 | 47,779 |

| Recon-3D | Photogrammetry | Point cloud | 809,519 | 25,158 | |

| KIRI Engine | NSR | Mesh | 58,940 | 57,543 | |

| KIRI Engine | 3DGS | Mesh | 405,825 | 114,538 | |

| Luma AI | NeRF | Point cloud | 2,062,468 | 147,983 | |

| 3 | Recon-3D | LiDAR | Point cloud | 1,446,441 | 197,414 |

| Recon-3D | Photogrammetry | Point cloud | 540,772 | 33,681 | |

| KIRI Engine | NSR | Mesh | 69,567 | 42,692 | |

| KIRI Engine | 3DGS | Mesh | 426,957 | 108,988 | |

| Luma AI | NeRF | Point cloud | 2,050,007 | 270,635 |

| Morphometric Measurement | Cow | Manual Measure (cm) | Recon-3D LiDAR | Recon-3D Photogrammetry | KIRI Engine NSR | KIRI Engine 3DGS | Luma AI NeRF | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure (cm) | r.e. (%) | Measure (cm) | r.e. (%) | Measure (cm) | r.e. (%) | Measure (cm) | r.e. (%) | Measure (cm) | r.e. (%) | |||

| Body Length | 1 | 175.00 | 172.22 | 1.59 | 172.07 | 1.67 | 164.76 | 5.85 | 168.84 | 3.52 | 177.92 | −1.67 |

| 2 | 172.50 | 182.42 | −5.75 | 167.25 | 3.04 | 209.74 | −21.59 | 176.33 | −2.22 | 184.51 | −6.96 | |

| 3 | 164.00 | 164.82 | −0.50 | 177.66 | −8.33 | 168.93 | −3.01 | 177.05 | −7.96 | 164.18 | −0.11 | |

| Chest Height | 1 | 76.67 | 83.86 | −9.38 | 81.44 | −6.22 | 79.88 | −4.19 | 79.69 | −3.94 | 82.99 | −8.24 |

| 2 | 75.00 | 76.46 | −1.95 | 77.08 | −2.77 | 98.48 | −31.31 | 82.22 | −9.63 | 84.98 | −13.31 | |

| 3 | 75.00 | 73.24 | 2.35 | 77.98 | −3.97 | 69.03 | 7.96 | 77.48 | −3.31 | 76.66 | −2.21 | |

| Chest Width | 1 | 57.33 | 57.73 | −0.70 | 61.49 | −7.26 | 60.19 | −4.99 | 57.45 | −0.21 | 51.63 | 9.94 |

| 2 | 56.67 | 60.72 | −7.15 | 78.77 | −39.00 | 72.66 | −28.22 | 64.99 | −14.68 | 55.26 | 2.49 | |

| 3 | 50.50 | 50.11 | 0.77 | 49.20 | 2.57 | 44.58 | 11.72 | 57.26 | −13.39 | 52.80 | −4.55 | |

| Rump Length | 1 | 56.67 | 49.78 | 12.16 | 52.54 | 7.29 | 53.73 | 5.19 | 44.52 | 21.44 | 56.95 | −0.49 |

| 2 | 56.00 | 53.98 | 3.61 | 57.51 | −2.70 | 61.05 | −9.02 | 50.20 | 10.36 | 54.77 | 2.20 | |

| 3 | 49.67 | 51.13 | −2.94 | 53.26 | −7.23 | 54.37 | −9.46 | 56.54 | −13.83 | 50.02 | −0.70 | |

| Wither Height | 1 | 149.33 | 144.80 | 3.03 | 145.77 | 2.38 | 150.66 | −0.89 | 149.20 | 0.09 | 159.47 | −6.79 |

| 2 | 149.67 | 147.44 | 1.49 | 151.07 | −0.94 | 167.71 | −12.05 | 152.05 | −1.59 | 169.51 | −13.26 | |

| 3 | 148.67 | 143.25 | 3.65 | 147.46 | 0.81 | 148.26 | 0.28 | 150.94 | −1.53 | 149.12 | −0.30 | |

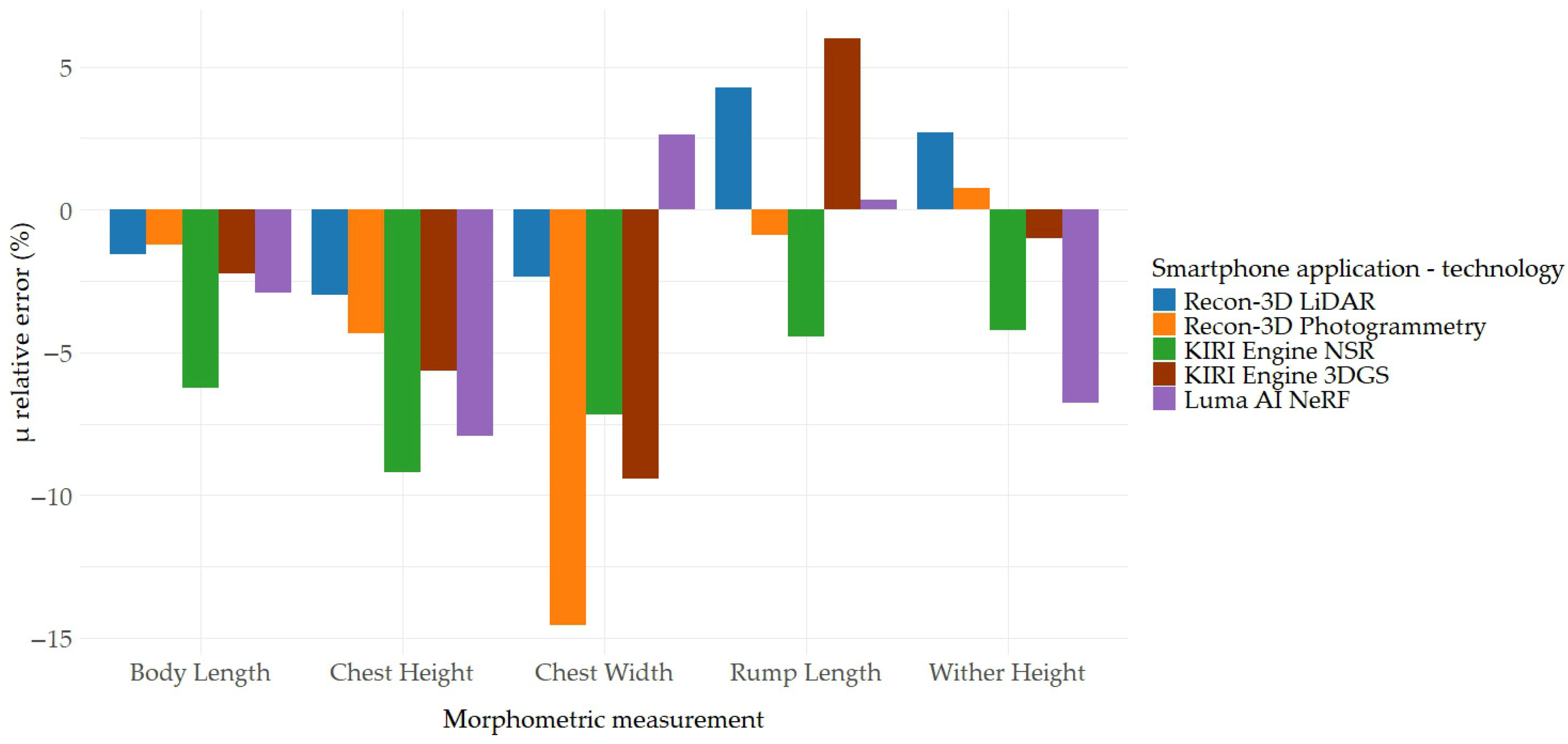

| Morphometric Measurement | Recon-3D LiDAR | Recon-3D Photogrammetry | KIRI Engine NSR | KIRI Engine 3DGS | Luma AI NeRF | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| µ r.e. (%) | σ r.e. (%) | r | µ r.e. (%) | σ r.e. (%) | r | µ r.e. (%) | σ r.e. (%) | r | µ r.e. (%) | σ r.e. (%) | r | µ r.e. (%) | σ r.e. (%) | r | |

| Body Length | −1.55 | 3.78 | 0.67 | −1.21 | 6.21 | −0.77 | −6.25 | 14.00 | 0.22 | −2.22 | 5.74 | −0.73 | −2.91 | 3.59 | 0.86 |

| Chest Height | −2.99 | 5.93 | 0.96 | −4.32 | 1.75 | 0.98 | −9.18 | 20.10 | −0.15 | −5.63 | 3.48 | −0.04 | −7.92 | 5.56 | 0.29 |

| Chest Width | −2.36 | 4.21 | 0.93 | −14.56 | 21.73 | 0.76 | −7.16 | 20.06 | 0.85 | −9.43 | 8.01 | 0.44 | 2.63 | 7.25 | 0.11 |

| Rump Length | 4.28 | 7.57 | 0.12 | −0.88 | 7.43 | 0.30 | −4.43 | 8.33 | 0.35 | 5.99 | 18.04 | −0.92 | 0.34 | 1.62 | 0.97 |

| Wither Height | 2.72 | 1.11 | 0.95 | 0.75 | 1.66 | 0.52 | −4.22 | 6.81 | 0.83 | −1.01 | 0.95 | 0.21 | −6.78 | 6.48 | 0.98 |

| Morphometric Measurement | Recon-3D LiDAR | Recon-3D Photogrammetry | KIRI Engine NSR | KIRI Engine 3DGS | Luma AI NeRF | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | MAPE | RMSE | MAPE | RMSE | MAPE | RMSE | MAPE | RMSE | MAPE | |

| Body Length | 5.97 | 2.61 | 8.62 | 4.35 | 22.48 | 10.15 | 8.62 | 4.57 | 7.14 | 2.91 |

| Chest Height | 4.36 | 4.56 | 3.46 | 4.32 | 14.11 | 14.48 | 4.74 | 5.62 | 6.89 | 7.92 |

| Chest Width | 2.36 | 2.87 | 13.01 | 16.28 | 9.98 | 14.98 | 6.19 | 9.43 | 3.64 | 5.66 |

| Rump Length | 4.23 | 6.23 | 3.28 | 5.74 | 4.33 | 7.89 | 8.73 | 15.21 | 0.75 | 1.13 |

| Wither Height | 4.28 | 2.72 | 2.32 | 1.38 | 10.45 | 4.41 | 1.9 | 1.07 | 12.87 | 6.78 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marchegiani, S.; Chiappini, S.; Choudhury, M.A.M.; E, G.; Trombetta, M.F.; Pasquini, M.; Marcheggiani, E.; Ceccobelli, S. Affordable 3D Technologies for Contactless Cattle Morphometry: A Comparative Pilot Trial of Smartphone-Based LiDAR, Photogrammetry and Neural Surface Reconstruction Models. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2567. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242567

Marchegiani S, Chiappini S, Choudhury MAM, E G, Trombetta MF, Pasquini M, Marcheggiani E, Ceccobelli S. Affordable 3D Technologies for Contactless Cattle Morphometry: A Comparative Pilot Trial of Smartphone-Based LiDAR, Photogrammetry and Neural Surface Reconstruction Models. Agriculture. 2025; 15(24):2567. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242567

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarchegiani, Sara, Stefano Chiappini, Md Abdul Mueed Choudhury, Guangxin E, Maria Federica Trombetta, Marina Pasquini, Ernesto Marcheggiani, and Simone Ceccobelli. 2025. "Affordable 3D Technologies for Contactless Cattle Morphometry: A Comparative Pilot Trial of Smartphone-Based LiDAR, Photogrammetry and Neural Surface Reconstruction Models" Agriculture 15, no. 24: 2567. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242567

APA StyleMarchegiani, S., Chiappini, S., Choudhury, M. A. M., E, G., Trombetta, M. F., Pasquini, M., Marcheggiani, E., & Ceccobelli, S. (2025). Affordable 3D Technologies for Contactless Cattle Morphometry: A Comparative Pilot Trial of Smartphone-Based LiDAR, Photogrammetry and Neural Surface Reconstruction Models. Agriculture, 15(24), 2567. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242567