1. Introduction

Accurate estimation of crop water requirements is crucial for the design and management of irrigation systems. When considering soil water balance, crop water requirements primarily depend on estimating crop evapotranspiration (ET

c). A widely adopted and straightforward method for estimating ET

c, initially proposed by [

1], consists of multiplying a crop-specific coefficient (K

c), which accounts for the specific physiological and morphological traits, by the reference evapotranspiration (ET

o) for a grass surface [

2]. ET

o represents the atmospheric demand for water by integrating soil evaporation and plant transpiration from a standardised reference surface. The FAO Penman–Monteith method (FAO56 PM) defines this reference surface as a hypothetical grass crop with specific characteristics, including a height of 0.12 m, a surface albedo of 0.23, and a constant surface resistance of 70 s m

−1 under standard conditions [

2].

The FAO56 PM equation, regarded as the standard method for estimating ET

o, requires multiple meteorological inputs, including maximum and minimum air temperatures (T

max and T

min), solar radiation (R

s), air humidity, and wind speed (u

2). However, due to the frequent scarcity or unreliability of weather data in some regions, different simplified methods with reduced input requirements have been proposed. One of these variants is the temperature-based model proposed by the FAO, hereafter referred to as PMT, which relies primarily on temperature data, often the most recorded and, in many datasets, the only available variables [

3]. Another widely used temperature-based model is the Hargreaves–Samani (HS) equation [

4]. This method has become popular because of its simplicity and minimal data requirements. In this sense, the development of temperature-based methods for estimating ET

o is supported by several reasons. On the one hand, temperature, along with Rs, accounts for most of the variability in ET

o [

5], and the daily temperature range can indirectly reflect other climatic factors such as humidity, cloud cover, and advection-related processes [

6,

7,

8]. Moreover, temperature is the most widely monitored and easily measured meteorological variable, often recorded even in areas lacking complete weather datasets [

9]. As a result, numerous simplified models using only temperature inputs have been proposed across diverse climates [

10]. While many of these models aim to reproduce the results of the FAO56 PM method, they often lack its physical foundations [

11]. For this reason, FAO recommends estimating any missing inputs and preserving the original formulation to maintain the integrity of the physical relationships between variables, an approach that is sometimes overlooked in practice [

11].

Several studies have shown that both PMT and HS equations can provide accurate ET

o estimates, with relatively low errors when compared to the FAO56 PM reference method, e.g., [

3,

10,

12,

13]. Although these alternatives improve applicability in data-limited contexts, they often require local calibration or methodological adjustments to achieve acceptable accuracy [

14,

15]. Calibration procedures often rely on FAO56 PM estimates, typically involving the adjustment of a single average calibration coefficient per site. One of the main limitations of these calibrated models is their lack of transferability, as the calibration remains site-specific and cannot be applied to locations without prior local parameterisation. In most cases, the HS parameters are calibrated using the entire dataset from a given station, or even from a group of stations, resulting in a single set of factors per location. In contrast, only a limited number of studies have explored the monthly calibration of HS parameters, generally focusing on deriving monthly coefficients rather than examining the monthly performance of both calibrated and non-calibrated equations to determine whether seasonal trends justify such calibration [

16]. Using a single correction factor for an entire station may not adequately address systematic biases occurring at shorter temporal scales. Therefore, applying a month-specific coefficient enables the model to capture seasonal variability more effectively, improving the accuracy of ET

o estimates and, consequently, crop irrigation requirements.

Alongside these empirical methods, data-driven techniques, particularly machine learning (ML) models, have become valuable alternatives for ET

o estimation when input data are limited. Among these, artificial neural networks (ANN) [

17], support vector machines (SVM) [

18,

19], gene expression programming (GEP) [

20,

21], and random forest (RF) [

22,

23], among others, have been recognised for their efficiency in ET

o prediction using minimal input variables. Despite their strong predictive abilities, these methods do not inherently incorporate the physical principles underlying the FAO56 PM framework [

11]. These models are trained with site-specific datasets, and their estimation accuracy typically decreases outside the training context, although it remains higher than that of temperature-based models. To simulate actual prediction conditions with limited or even absent climatic records, some studies assessed the generalisation ability of ML models using spatial k-fold validation, i.e., reserving the complete data set of a different independent station in each iteration for testing the models, e.g., [

20]. Moreover, previously to model training, preliminary techniques such as clustering stations with similar climatic characteristics may help to enhance the transferability of models across regions [

24].

Another experimental method to determine ET is the use of weighing lysimeters, which estimate water loss based on the components of the soil water balance within a controlled cultivation system [

25]. In cases where the crop grown on the lysimeter surface meets the standard reference conditions, the recorded evapotranspiration can be regarded as ET

o [

26]. However, despite their potential to provide highly accurate short-term ET

o measurements, both lysimeters and other advanced experimental tools, such as eddy covariance flux towers, present several limitations. These include high costs, complex installation and maintenance, the need for sufficient fetch, and intensive data processing requirements [

27]. Moreover, the limited spatial extent of typical meteorological station plots may hinder these instruments from capturing representative surface conditions [

28]. As a result, direct ET

o measurements are rarely available and/or fully reliable. In this context, some studies have assessed the calibration and/or validation of empirical and/or ML models against lysimeter-derived ET

o values instead of the FAO56 PM reference method, e.g., [

16,

29]. However, it is important to note that if the lysimeter system does not maintain the FAO standard reference crop conditions, this may lead to biased conclusions regarding model performance.

As evidenced in the literature, the calibration and validation of ET

o methods, such as empirical equations and ML models, have been extensively studied. However, most studies focus on achieving high accuracy in daily ET

o estimates, based on the premise that precise daily irrigation doses are necessary. Nonetheless, considering that the soil can act as a buffer for water availability, it may be more realistic to require accurate estimations only for accumulated ET values over extended periods, such as a week, a common timeframe used for scheduling and adjusting irrigation practices. Some studies have assessed the reliability of ET

o estimates over extended periods. For instance, although the HS equation has shown reasonable accuracy daily, Hargreaves et al. [

30] noted that its performance improves when applied to 5-day or longer intervals. This is because short-term estimates tend to exhibit greater variability due to factors such as shifting weather fronts and fluctuations in wind speed and cloud cover. However, these results referred to averaged ET

o values, not to cumulated ones.

This paper has two main objectives. First, it evaluates the implications of using grass-reference lysimeter observations as benchmarks for assessing ETo models, compared with the recommended practice of using FAO56 PM as the target. Second, it analyses the practical implications of daily ETo model accuracy for irrigation scheduling by comparing the performance of different ETo modelling approaches when evaluated on both daily and accumulated ETo values at trial, weekly, fortnightly, monthly, and annual intervals. Daily and accumulated ETo estimates were calculated for all models and timescales, using FAO56 PM estimates and lysimeter measurements as target values, to assess how discrepancies in daily ETo propagate over time and may affect irrigation decision making at different intervals.

3. Results

3.1. Model Performance Assessment Against FAO56 PM Targets

Table 1 presents the global performance indicators of the considered models, divided by timescale, at Albacete and Badajoz, using FAO56 PM estimations as benchmarks. In Albacete, all models showed a gradual decrease in RRMSE as the accumulation interval increased, indicating, as expected, that model accuracy improved when ET

o values were aggregated over longer timescales. For the HS model, RRMSE values ranged from 0.179 for daily ET

o to 0.025 for annual estimates, with 0.140 for trial, 0.116 for weekly, 0.095 for fortnightly, and 0.076 for monthly. The reduction between daily and weekly scales was 6.3%, followed by 4.0% from weekly to monthly, and 5.1% from monthly to annual, resulting in a total absolute decrease of approximately 15.4% across the entire range. The corresponding MAE values ranged from 0.57 mm day

−1 to 18.45 mm year

−1, with intermediate values of 1.07 mm (trial), 1.77 mm (week), 2.96 mm (fortnight), and 4.81 mm (month). Similarly, the PMT model displayed a very comparable pattern, with RRMSE values of 0.183 (daily), 0.134 (trial), 0.118 (week), 0.099 (fortnight), 0.084 (month), and 0.032 (annual). The decrease was more gradual, amounting to 6.5% from daily to weekly intervals, 3.5% from weekly to monthly intervals, and 5.2% from monthly to annual intervals, for a total reduction of roughly 15.1%. MAE values ranged from 0.59 mm day

−1 to 25.68 mm year

−1, with intermediate figures of 1.03 mm (trial), 1.87 mm (week), 3.19 mm (fortnight), and 5.30 mm (month). Conversely, the ANN6 model mainly differed in the magnitude of errors, which were substantially smaller across all timescales. RRMSE decreased from 0.070 at the daily scale to 0.063 (trial), 0.057 (week), 0.052 (fortnight), 0.048 (month), and 0.028 (annual). The reduction was therefore 1.3% from daily to weekly, 0.9% from weekly to monthly, and 2.0% from monthly to annual, leading to a total absolute decrease of 4.2%. The corresponding MAE values ranged from 0.20 mm day

−1 to 22.65 mm year

−1, with intermediate values of 0.43 mm (trial), 0.80 mm (week), 1.48 mm (fortnight), and 2.69 mm (month). Overall, all models showed a consistent pattern of decreasing error as the accumulation interval increased, indicating that daily discrepancies tend to diminish when ET

o is aggregated over multi-day or seasonal periods. Thus, even for the temperature-based models, the relative discrepancy with FAO56 PM becomes significantly smaller at weekly and longer timescales, while ANN6 displays more minor additional improvements with aggregation because its daily agreement with FAO56 PM is already high.

When comparing the models, differences were substantial at the daily scale (RRMSE = 0.179 and 0.183 for HS and PMT, respectively, versus 0.070 for ANN6), indicating that ANN6 achieved higher accuracy on this scale. However, at weekly and fortnightly intervals, the gap between temperature-based and data-driven models narrowed considerably (RRMSE approximately 0.10–0.12 for HS/PMT versus 0.05–0.06 for ANN6). At monthly to yearly scales, the differences became minimal, with all models showing RRMSE ≤ 0.08 and converging to values near 0.03–0.04 at the most extended periods. The calibrated versions of HS and PMT (HS_cal and PMT_cal) displayed the same decreasing trend, with RRMSE values ranging from 0.174 to 0.023 and from 0.176 to 0.024, respectively, across the daily-to-yearly spectrum. ANN3 and ANN3_month produced intermediate results, with RRMSE values ranging from 0.164 to 0.023 and from 0.166 to 0.022, respectively, consistent with the general pattern seen in the other models. Slight differences between calibrated and non-calibrated configurations suggest that variations due to calibration or ANN structure were minor compared to the effect of the accumulation interval. Furthermore, the highest R2 values were observed for monthly accumulated ETo across all models considered. These patterns reveal that model choice has a greater impact when daily ETo is assessed, whereas differences between models diminish as ETo is aggregated over weekly or more extended periods. The limited effect of calibration also implies that, under FAO56 PM benchmarking, the primary factor driving performance improvements is the timescale of ETo aggregation rather than detailed adjustments of model parameters.

In Badajoz, similar results were observed. All models exhibited a steady decline in RRMSE with increasing accumulation intervals, following the same general trend observed in Albacete. For HS, RRMSE values were 0.155 for daily ETo, 0.132 for trial, 0.113 for weekly, 0.101 for fortnightly, 0.093 for monthly, and 0.070 for annual estimations. The decrease between daily and weekly intervals was 4.2%, 2.0% from weekly to monthly and 2.3% from monthly to annual, amounting to an overall reduction of 8.5%. Corresponding MAE values ranged from 0.61 mm day−1 to 65.25 mm year−1. PMT followed a very similar pattern, with RRMSE values of 0.168 (daily), 0.133 (trial), 0.126 (weekly), 0.112 (fortnight), 0.103 (month), and 0.066 (annual), with an overall absolute reduction of 10.2%. MAE ranged from 0.67 mm day−1 to 63.64 mm year−1. Conversely, ANN6 maintained significantly lower errors, with RRMSE of 0.057 (daily), 0.052 (trial), 0.047 (weekly), 0.044 (fortnight), 0.042 (month), and 0.029 (annual). The reductions were 1.0% from daily to weekly, 0.5% from weekly to monthly, and 1.8% from monthly to annual, totalling 2.8% across the day-to-year spectrum. MAE values ranged from 0.19 mm day−1 to 25.53 mm year−1, with intermediate values of 0.43 mm (trial) and 0.86 mm (week).

Across models, differences remained evident at the daily scale (RRMSE = 0.155 and 0.168 for HS and PMT, respectively, versus 0.057 for ANN6), but, as in Albacete, these differences significantly diminished with increasing accumulation intervals. At weekly and fortnightly scales, RRMSE values were 0.11–0.13 for HS and PMT, compared to 0.05–0.06 for ANN6, while over monthly to annual intervals, all models converged to values below 0.08, with differences less than 0.03. HS_cal and PMT_cal showed nearly identical patterns, with RRMSE values ranging from 0.149 to 0.057 and from 0.159 to 0.059, respectively, across daily to annual scales. Similarly, ANN3 and ANN3_month produced intermediate results (0.126–0.050 and 0.124–0.046), displaying performance trends similar to those observed in Albacete. The fact that these patterns closely mirror those observed in Albacete suggests that the decrease in error with increasing accumulation interval is consistent across the two semi-arid Mediterranean locations analysed.

3.2. Performance of Models Against Lysimeter Targets

Table 2 presents the global performance indicators of the considered models, split by timescale, for Albacete and Badajoz, using lysimeter measurements as the benchmark. In Albacete, all models exhibited higher RRMSE values when evaluated against lysimeter data than against FAO56 PM, yet the gradual improvement with more extended accumulation periods remained evident. For HS, RRMSE values dropped from 0.221 at the daily scale to 0.179 (trial), 0.155 (weekly), 0.132 (fortnightly), 0.115 (monthly), and 0.054 (annual). The reduction between daily and weekly periods was 6.6%, followed by 4.0% from weekly to monthly and 6.1% from monthly to annual, giving an overall decrease of 16.6%. MAE values ranged from 0.71 mm day

−1 to 44.78 mm year

−1. The PMT model followed a comparable progression, with RRMSE values of 0.224 (daily), 0.167 (trial), 0.154 (weekly), 0.133 (fortnight), 0.118 (month), and 0.050 (annual). The total reduction reached 17.4%, and MAE varied between 0.73 mm day

−1 and 40.69 mm year

−1. Conversely, ANN6 produced considerably lower errors at all timescales, with RRMSE decreasing from 0.144 (daily) to 0.115 (trial), 0.100 (week), 0.084 (fortnight), 0.076 (month), and 0.038 (annual). The corresponding decline was 10.6%, and MAE ranged from 0.46 mm day

−1 to 30.68 mm year

−1. Thus, although all models exhibited larger errors against lysimeter ET

o than against FAO56 PM, the progressive reduction in RRMSE with increasing accumulation interval remained evident, indicating that daily discrepancies were also attenuated when ET

o was aggregated over multi-day or seasonal periods under lysimeter benchmarking.

Regarding differences among models, the most considerable contrasts occurred at the daily scale (RRMSE of 0.221 and 0.224 for HS and PMT vs. 0.144 for ANN6), but decreased notably as the period lengthened. At weekly and fortnightly resolutions, RRMSE values ranged from 0.13 to 0.15 for HS and PMT and approximately 0.10 for ANN6, while at monthly and annual levels, all models presented values below 0.08. HS_cal and PMT_cal exhibited a very similar evolution (RRMSE of 0.213–0.045 and 0.215–0.047, respectively), whereas ANN3 and ANN3_month showed intermediate results (0.204–0.045 and 0.207–0.046).

In the case of Badajoz, the same overall pattern was observed. All models yielded higher RRMSE values under lysimeter benchmarking, although the decrease with increasing aggregation remained consistent. HS showed RRMSE values of 0.255 (daily), 0.207 (trial), 0.174 (weekly), 0.154 (fortnight), 0.131 (month), and 0.070 (annual). The reduction from daily to weekly was 8.1%, followed by 4.3% from weekly to monthly and 6.1% from monthly to annual, resulting in an overall decrease of 18.5%. MAE values varied between 0.86 mm day−1 and 58.43 mm year−1. PMT behaved in parallel, with RRMSE values of 0.266 (daily), 0.190 (trial), 0.189 (weekly), 0.168 (fortnight), 0.144 (month), and 0.078 (annual), corresponding to a total reduction of 18.8%. MAE ranged from 0.92 mm day−1 to 66.10 mm year−1. In contrast, ANN6 again showed more minor errors, with RRMSE values of 0.258 (daily), 0.194 (trial), 0.164 (weekly), 0.151 (fortnight), 0.130 (month), and 0.086 (annual). The total decrease was 17.2%, and MAE ranged from 0.90 mm day−1 to 74.74 mm year−1.

Between models, the most pronounced differences were again found at the daily and weekly levels (RRMSE ≈ 0.22–0.27 for HS/PMT vs. 0.26 for ANN6), whereas from fortnightly to annual periods, all models performed more similarly, with RRMSE ≤ 0.15 and converging towards 0.07–0.09 at the most extended intervals. HS_cal and PMT_cal maintained the same decreasing tendency (RRMSE = 0.243–0.048 and 0.248–0.050, respectively), while ANN3 and ANN3_month remained intermediate (0.240–0.047 and 0.237–0.046). Overall, slight differences were observed between calibrated and non-calibrated versions, and RRMSE variability among models diminished progressively with the length of the accumulation period. Compared with the FAO56 PM benchmark (

Table 1), these daily and weekly RRMSE values show that ANN6 no longer exhibits a clear advantage over HS and PMT when the lysimeter is used as the reference, particularly in Badajoz. In addition, R

2 values were slightly higher in Albacete (up to 0.982) than in Badajoz (up to 0.940), confirming a more stable agreement between estimated and benchmark ET

o in the former site and suggesting that lysimeter-based targets were more affected by local variability at Badajoz.

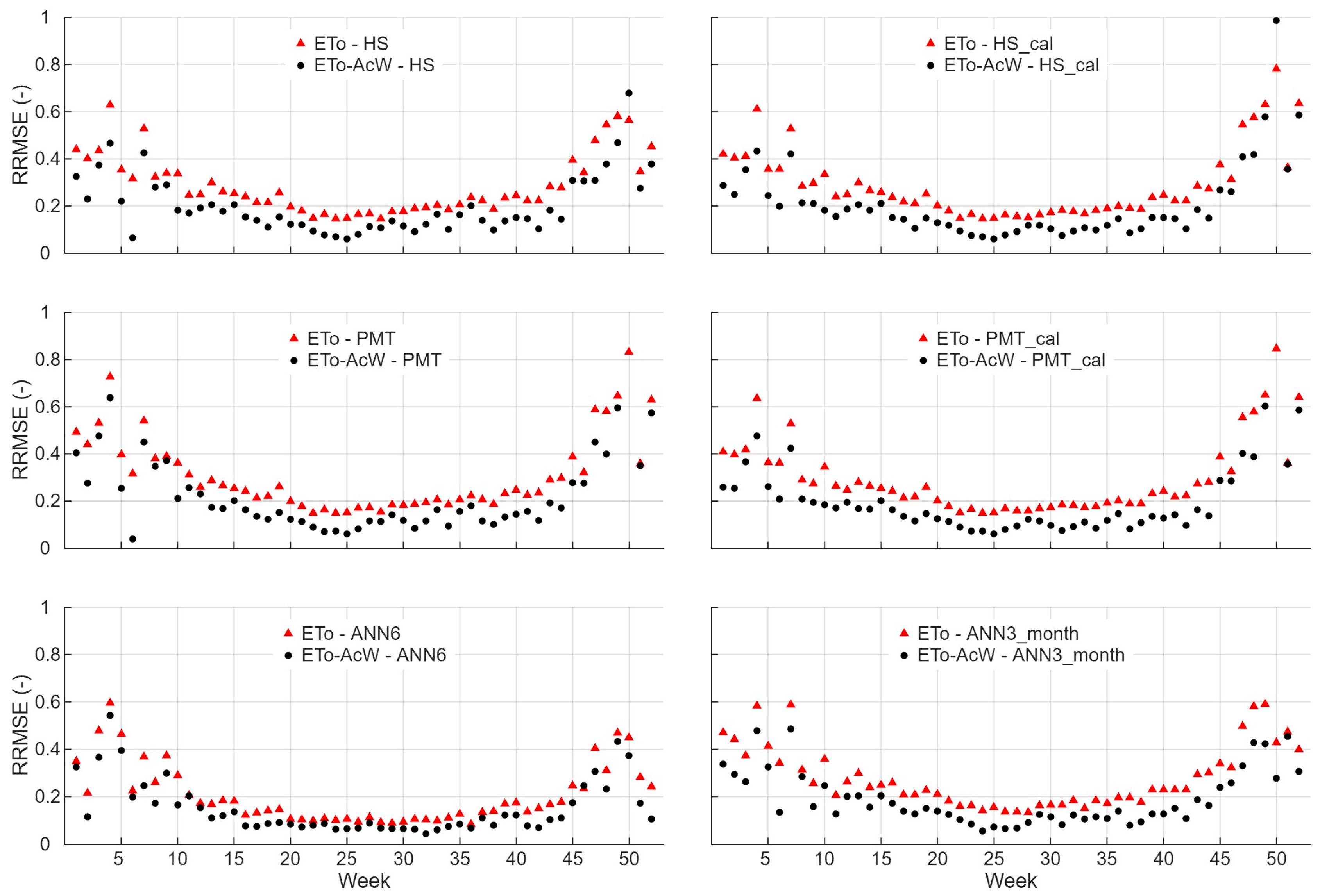

3.3. Seasonal Variation of Model Performance Under FAO56 PM and Lysimeter Benchmarks

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 show the weekly evolution of RRMSE for daily ET

o and weekly accumulated ET

o (ET

o-AcW) in Albacete and Badajoz, respectively, using FAO56 PM estimations as the benchmark.

As observed, the model accuracy varied throughout the year, with lower performance during the cooler weeks (November–January) and higher accuracy during the warmer period (June–August). In Albacete, daily ETo RRMSE values for ANN6 ranged from 0.035 (week 26) to 0.180 (week 52), while in Badajoz, they ranged from 0.024 (week 30) to 0.174 (week 5). For ETo-AcW, the corresponding ranges were 0.025 (week 26)–0.159 (week 52) in Albacete and 0.021 (week 30)–0.146 (week 49) in Badajoz. Among the temperature-based models, RRMSE values for ETo-AcW ranged from 0.040 (week 34) to 0.483 (week 48) for HS, from 0.041 (week 25) to 0.635 (week 50) for PMT, and from 0.043 (week 25) to 0.594 (week 51) for ANN3_month in Albacete. In Badajoz, the ranges were 0.066–0.402 for HS (weeks 26 and 49, respectively), 0.071 (week 35)–0.613 (week 48) for PMT, and 0.031 (week 33)–0.594 (week 49) for ANN3_month. The most minor difference between daily and weekly RRMSE occurred around mid-summer (weeks 25–30), while the largest occurred in late autumn (weeks 48–52). Overall, the seasonal pattern was more pronounced for daily ETo than for ETo-AcW, indicating that model performance is strongly modulated by the annual cycle of atmospheric demand, with more stable behaviour during the peak evaporative season and enhanced sensitivity to synoptic variability during the colder weeks.

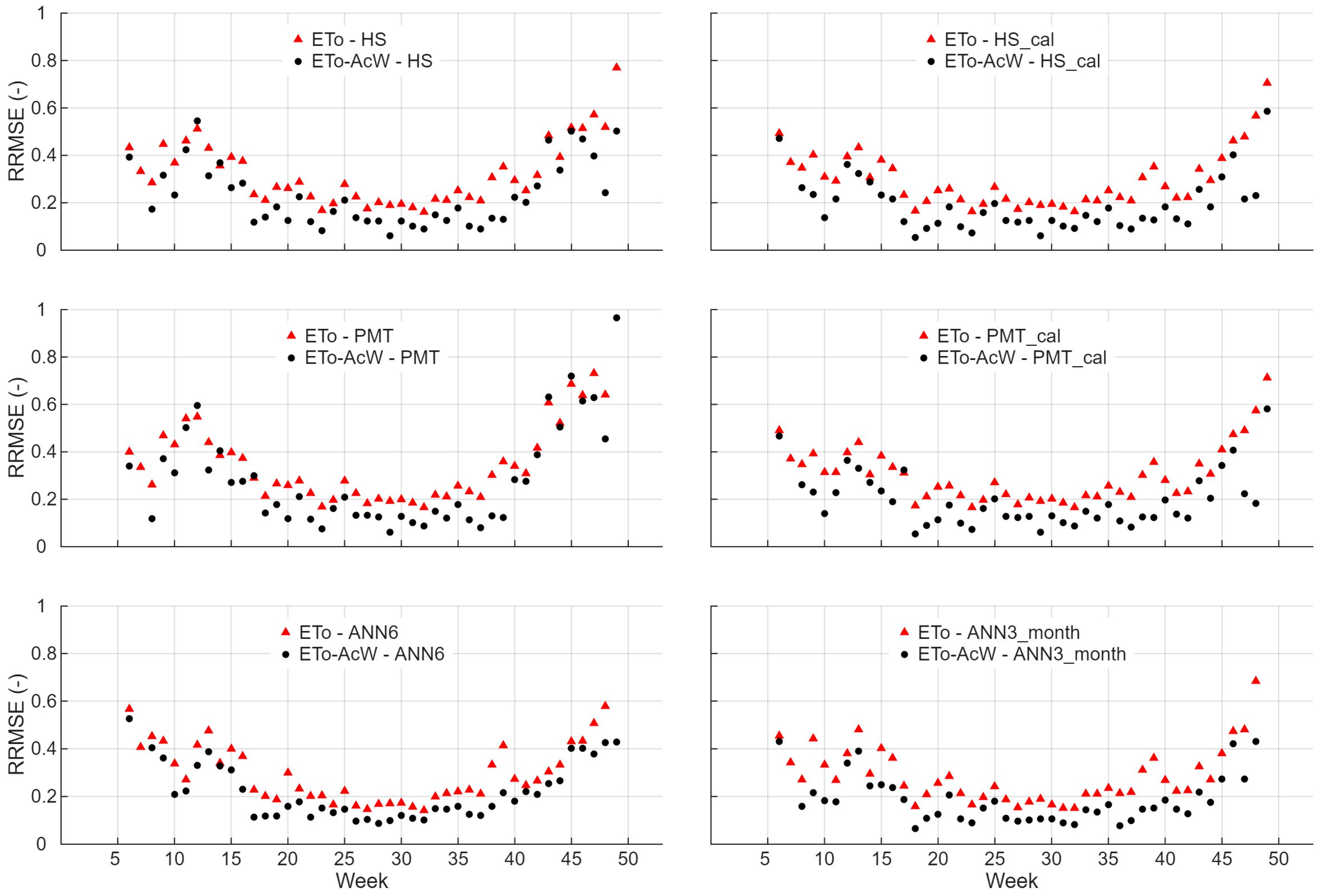

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 show the same analysis using lysimeter measurements as benchmarks. In Albacete, daily ET

o RRMSE values presented a minimum of approximately 0.15 for both HS (week 24) and PMT (week 22) models, either calibrated or not. Maximum errors were 0.63 (week 4) for HS, 0.83 (week 50) for PMT, 0.59 (week 49) for ANN3_month, and 0.60 (week 4) for ANN6. The corresponding RRMSE ranges were 0.13–0.59 (weeks 28–49) for ANN3_month and 0.09–0.60 (weeks 36–4) for ANN6. The corresponding RRMSE ranges for ET

o-AcW were 0.04 (week 25)–0.99 (week 50) for HS_cal, 0.04 (week 6)–0.64 (week 4) for PMT, 0.06 (week 24)–0.48 (week 7) for ANN3_month, and 0.04 (week 32)–0.54 (week 4) for ANN6. In Badajoz, daily ET

o errors ranged from 0.16 (week 32) to 0.77 (week 49) for HS, 0.16 (week 32) to 0.73 (week 47) for PMT, 0.15 (week 32) to 0.68 (week 48) for ANN3_month, and 0.14 (week 32) to 0.58 (week 48) for ANN6. For ET

o-AcW, they varied between 0.06 (week 29)–0.55 (week 12) for HS, 0.06 (week 29)–0.97 (week 49) for PMT, 0.07 (week 18)–0.43 (week 6) for ANN3_month, and 0.09 (week 28)–0.53 (week 6) for ANN6. As in the FAO56 PM-based analysis, weekly accumulated estimates (ET

o-AcW) were consistently more accurate than daily estimates, except for certain winter weeks, when missing or sparse data led to occasional deviations. In some winter weeks, RRMSE peaks exceeded 1.00 for ET

o-AcW, reaching 1.09 in Albacete (HS_cal) and 1.34 in Badajoz (ANN3_month). Occasional peaks in daily ET

o were also observed, with maximum values of 2.94 for ANN3_month in Badajoz. These peaks occurred during periods of very low reference ET

o and reduced data availability, when small absolute discrepancies translate into significant relative errors. Overall, seasonal RRMSE patterns were consistent across sites and benchmarks, with higher variability and larger errors observed under the lysimeter reference than under FAO56 PM, particularly during the coldest part of the year, while differences among models diminished during summer.

In summary, across both sites and benchmarks, all models exhibited a consistent reduction in RRMSE and MAE as the accumulation interval increased from daily to trial, weekly, fortnightly, monthly, and annual scales (

Table 1 and

Table 2). Under FAO56 PM benchmarking, daily RRMSE ranged approximately between 0.06 and 0.18, whereas at monthly and annual scales, it was below 0.08 for all models at both sites, with ANN6 showing the lowest errors throughout. When lysimeter measurements were used as benchmarks, daily RRMSE values increased to approximately 0.14–0.27, while weekly values remained below about 0.18, and monthly and annual RRMSE rarely exceeded 0.15. The seasonal analysis (

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5) further showed that errors were most significant and most variable during the coldest weeks of the year and smallest during summer, and that ET

o-AcW generally presented lower RRMSE than daily ET

o. Differences between temperature-based and ANN models were pronounced at the daily scale. Still, they became progressively smaller at weekly and longer intervals, so that at monthly and annual scales, the performance of all models converged within relatively narrow RRMSE ranges under both benchmarks.

4. Discussion

Our results show that model accuracy and dispersion highly depend on the chosen benchmark. Errors were systematically higher and more variable when lysimeter data were used, particularly during the coldest weeks of the year, whereas FAO56 PM produced lower and more stable values. This divergence suggests that the use of lysimeter measurements as a benchmark for assessing ET

o may reflect the influence of local environmental and operational factors. During winter, lysimeters can be affected by mechanical and microclimatic disturbances, such as frost, condensation, or the oasis and clothesline effects, which may alter the energy balance and induce anomalous fluxes. Their accuracy may also be influenced by restricted fetch and drainage dynamics, which are negligible under summer conditions but become significant in cold, calm periods [

43,

44]. Consequently, apparent model errors tend to increase when the lysimeter is used as the target, not necessarily because models perform worse, but because the benchmark itself becomes less representative of the standardised reference surface described in FAO56. These findings agree with [

45]. From a benchmarking perspective, our results indicate that, under the semi-arid Mediterranean conditions analysed, FAO56 PM behaves as a physically consistent and operationally robust reference. In contrast, lysimeter-based ET

o should be interpreted as an experimental benchmark whose representativeness is more sensitive to local conditions. Nevertheless, lysimeters might remain a valuable tool for directly measuring evapotranspiration under real conditions, especially during well-controlled periods or for model calibration purposes. During the winter season, when water-demanding crops such as barley, wheat, rapeseed, or leafy vegetables are commonly cultivated, special care should be taken when interpreting lysimeter data for irrigation planning.

When lysimeter data were used, the period of increased model error extended roughly from weeks 1–12 and 40–52, in line with previous findings [

16]. This broader high-error window indicates that non-calibrated models appeared to perform worse over a larger portion of the year when lysimeter data were used as the benchmark. However, this apparent degradation mainly reflects the greater sensitivity of lysimeter measurements under cold conditions, where limited reference availability and minor measurement errors disproportionately increase the overall error, particularly in Badajoz, where such conditions are more frequent. Thus, discrepancies between benchmarks are largely seasonal. FAO56 PM remains physically consistent throughout the year, while lysimeter measurements introduce additional variability in winter due to both environmental and operational factors. As a result, lysimeter observations can accentuate models’ tendency to under- or overestimate irrigation requirements, as reflected in higher MBE values. By contrast, FAO56 PM remains the widely recommended reference for ET

o estimation, since it is based on well-established physical principles and can be applied reliably whenever the required climatic data are available, unlike the constraints associated with lysimeter measurements, as also noted in [

46]. Therefore, in the context of semi-arid Mediterranean climates similar to those of Albacete and Badajoz, FAO56 PM appears to be a more suitable primary benchmark for model evaluation and ET

o estimation. At the same time, lysimeter observations provide complementary experimental evidence, particularly useful for detecting departures between physically based estimates and actual evapotranspiration under specific site conditions.

Regarding the effect of the irrigation interval on ET

o accuracy, model errors decreased consistently with more extended accumulation periods across all benchmarks and stations, confirming that temporal aggregation smooths daily discrepancies. Extending the estimation period from daily to multi-day or weekly irrigation intervals resulted in substantial reductions in RRMSE across all models, particularly for HS and PMT, which exhibited the most significant daily errors. This behaviour reflects a compensation effect among day-to-day deviations, which tend to cancel each other out when aggregated, provided that positive and negative errors are approximately balanced over time. Therefore, differences among models progressively diminished at longer timescales, and by monthly or annual intervals, their performance became nearly equivalent. Similar findings on the influence of timescales were reported by [

16], although their indicators were derived from daily estimates over a given period rather than from accumulated ET

o values. It is important to note that this compensation mainly affects the non-systematic component of the error. Systematic biases are only partially reduced and may still be reflected in MAE and MBE at longer timescales. Nevertheless, the systematic decrease in RRMSE and the relatively small MBE values observed at trial, weekly and fortnightly scales suggest that, under the semi-arid Mediterranean conditions considered here, a substantial fraction of daily errors tends to compensate in cumulative ET

o. This mechanism is likely to operate in other environments where daily deviations fluctuate around zero, and irrigation is scheduled over multi-day intervals. However, its magnitude should always be verified with local data. Conversely, in sites where simpler methods exhibit a persistent bias of the same sign, the scope for error compensation would be much more limited, and a marked reduction in error differences with aggregation should not be expected.

The practical implication is that trial, weekly, or fortnightly accumulated ET

o estimations provide a more realistic assessment framework for irrigation scheduling than daily values. Farmers usually plan irrigation in multi-day intervals, and the soil water buffer further mitigates daily fluctuations in evapotranspiration [

11]. Therefore, evaluating model performance exclusively at the daily scale can exaggerate differences that are not operationally significant, especially when irrigation decisions are based on cumulative water requirements. In this context, temperature-based models applied in this study might provide sufficiently accurate results when data availability is limited, while the more complex ANN formulations, such as ANN6, confirm that, under complete datasets, physically based estimates can be closely reproduced without substantially improving at longer intervals. In this sense, ANN6 was not proposed as an operational model but instead used as a complex reference to contextualise the performance of temperature-based approaches. Since it relies on the same meteorological inputs as FAO56 PM, its practical relevance is limited, as the reference equation can be directly computed when full datasets are available. Overall, these findings confirm that benchmark selection and temporal aggregation are crucial sources of variability in ET

o model performance. At the same time, differences among modelling approaches are significantly reduced at operational timescales relevant to irrigation management, so that the principal added value of this study lies in quantifying how benchmark choice and aggregation interval affect the apparent adequacy of well-established empirical and ANN-based methods under semi-arid Mediterranean conditions.

The ability of temperature-based methods and reduced-input ANN configurations to provide reasonable accuracy in the study area can be partly explained by the climatic setting. In semi-arid Mediterranean climates, key drivers of ET

o, such as net radiation, vapour pressure deficit, and aerodynamic demand, exhibit strong seasonal and synoptic co-variability with air temperature, so that temperature and solar radiation alone can account for a significant fraction of ET

o variability [

16]. As a result, T

max and T

min carry substantial information about the broader energy and moisture regime, which helps to explain the good performance of HS, PMT and the reduced-input ANN3 in our experiments, in line with previous work showing that reduced-input data-driven and empirical models can reach accuracies comparable to full-input formulations under similar Mediterranean conditions [

29]. Furthermore, the inputs used in ANN3 (T

max, T

min and R

a) are not independent: R

a and the seasonal cycle of air temperature are tightly coupled in these environments, indirectly capturing much of the variability in R

s and R

n. While this reliance on correlation structures enhances model performance in the present semi-arid Mediterranean conditions, it also implies that the empirical relationships learned by these models may not be directly transferable to markedly different climatic regimes without retraining and additional validation.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting these results. First, the analysis is based on long-term records from only two grass-reference lysimetric stations located in semi-arid Mediterranean environments: a cold semi-arid climate in Albacete and a hot-summer Mediterranean climate with Atlantic influence in Badajoz. Consequently, the quantitative indicators reported here are conditioned by these specific climatic and management conditions and by the quality and length of the available datasets. Second, the study does not include independent validation using reanalysis products or additional observational networks, so the robustness of the conclusions at regional scales cannot be assessed. These factors imply that the findings should be viewed as site-specific and primarily applicable to semi-arid Mediterranean environments with similar data availability. Nevertheless, the qualitative patterns identified are supported by physical reasoning and are expected to have a more general scope. In particular, the greater robustness of FAO56 PM as a benchmark compared with lysimeter targets in winter, the marked reduction in apparent model differences with increasing aggregation intervals, and the partial compensation of daily errors in cumulative ETo reflect mechanisms that can, in principle, operate at other sites. Their expression will depend on the local bias pattern of the simpler methods: where daily deviations fluctuate around zero, a substantial reduction in error differences with aggregation is likely, whereas in locations with a persistent over- or underestimation pattern, the scope for error compensation will be more limited. Thus, while the magnitude of the error reduction remains site-specific and should be verified with local data, the conceptual framework and the role of daily bias patterns in shaping cumulative ETo errors can be qualitatively extended to other networks, including those based solely on FAO P-M reference estimates.

5. Conclusions

This study evaluated the performance of temperature-based (HS and PMT) and neural network (ANN3 and ANN6) models for estimating daily ETo and its accumulated values over different time intervals at two contrasting Mediterranean sites in southeastern and southwestern Spain. The analysis was conducted using both the FAO56 PM equation and lysimeter measurements as benchmarks, and across different temporal aggregation intervals relevant to irrigation and water planning management, ranging from trial to weekly, fortnightly, monthly, and annual periods, under the semi-arid Mediterranean conditions represented by these sites. As a result, increasing the estimation interval from daily to weekly or fortnightly periods markedly reduced model errors and narrowed differences among approaches, indicating that temporal aggregation compensates for daily fluctuations and yields a more realistic assessment for irrigation scheduling. Since irrigation is usually not scheduled daily but rather at intervals that may account for soil water buffering and operational constraints, evaluating models at these timescales provides a more realistic measure of their accuracy. This reinforces the need to assess models beyond daily estimates, as otherwise they may lead to misleading conclusions for irrigation planning and on-farm decision-making. Most of the practically relevant error reduction was already achieved at weekly and fortnightly scales, while systematic components of the error remained visible in MAE and MBE at longer timescales.

The results also demonstrated that benchmark selection and temporal aggregation are crucial factors that govern model performance variability. Errors were systematically higher and more dispersed when lysimeter data were used, particularly during winter, likely reflecting the influence of environmental and operational factors under cold and calm conditions. By contrast, FAO56 PM provided more stable and consistent reference values throughout the year, confirming its suitability as the standard method for evaluating ETo models under semi-arid Mediterranean conditions. In this context, FAO56 PM emerges as a more suitable primary benchmark for model evaluation. In contrast, lysimeter-based ETo should be regarded as an experimental reference that is extremely valuable for validating and refining physically based formulations, but whose representativeness is more sensitive to local site characteristics and to the strict fulfilment of FAO reference crop requirements.

Finally, under complete climatic datasets, ANN6 achieved the highest accuracy when compared with FAO56 PM. Still, its relevance is primarily methodological, as it relies on the same inputs as the reference equation and is therefore not intended as an operational alternative. Temperature-based models, such as HS, PMT, exhibited stable behaviour across sites and benchmarks, and their accuracy at multi-day scales was comparable to that of more complex neural network formulations. These findings indicate that simple models remain robust and operationally useful tools in data-scarce or heterogeneous conditions, particularly when irrigation is scheduled over multi-day intervals, and a substantial part of daily errors tends to compensate in cumulative ETo. At the same time, FAO56 PM might be the most reliable alternative for reference evapotranspiration assessment when sufficient input data are available for its application. Lysimeter measurements, although subject to environmental variability, remain an essential component of experimental validation and contribute to refining physically based estimation approaches. The empirical relationships highlighted in this study are therefore best understood as site-specific and mainly relevant to semi-arid Mediterranean environments with similar climatic and management conditions. They are conditioned by the length and quality of the datasets available at the two experimental sites. The systematic decrease in model error observed at operational timescales indicates that, under these conditions, partial compensation of daily biases in cumulative ETo is likely to occur, provided that daily deviations fluctuate approximately around zero. This behaviour should nevertheless be confirmed with local data before extrapolating to markedly different climatic regimes or to locations where simpler methods exhibit a persistent over- or underestimation pattern.