Pollution Levels and Associated Health Risks of Heavy Metals in Agricultural Soils in Zhenjiang and Yangzhou, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

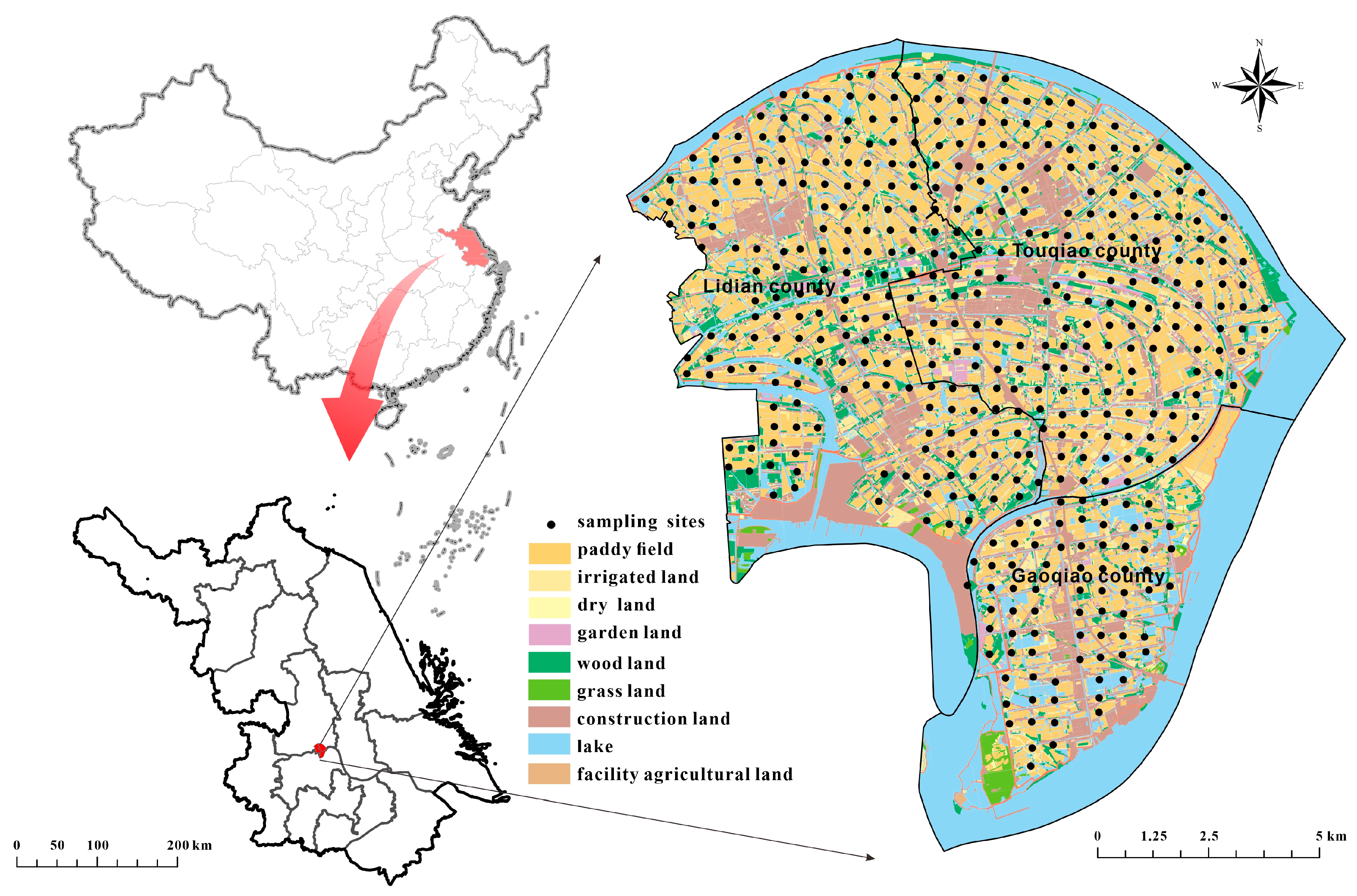

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Sample Collection and Pretreatment

2.3. Chemical Analysis

2.4. Pollution Indices

2.5. Risk Assessment Indices

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

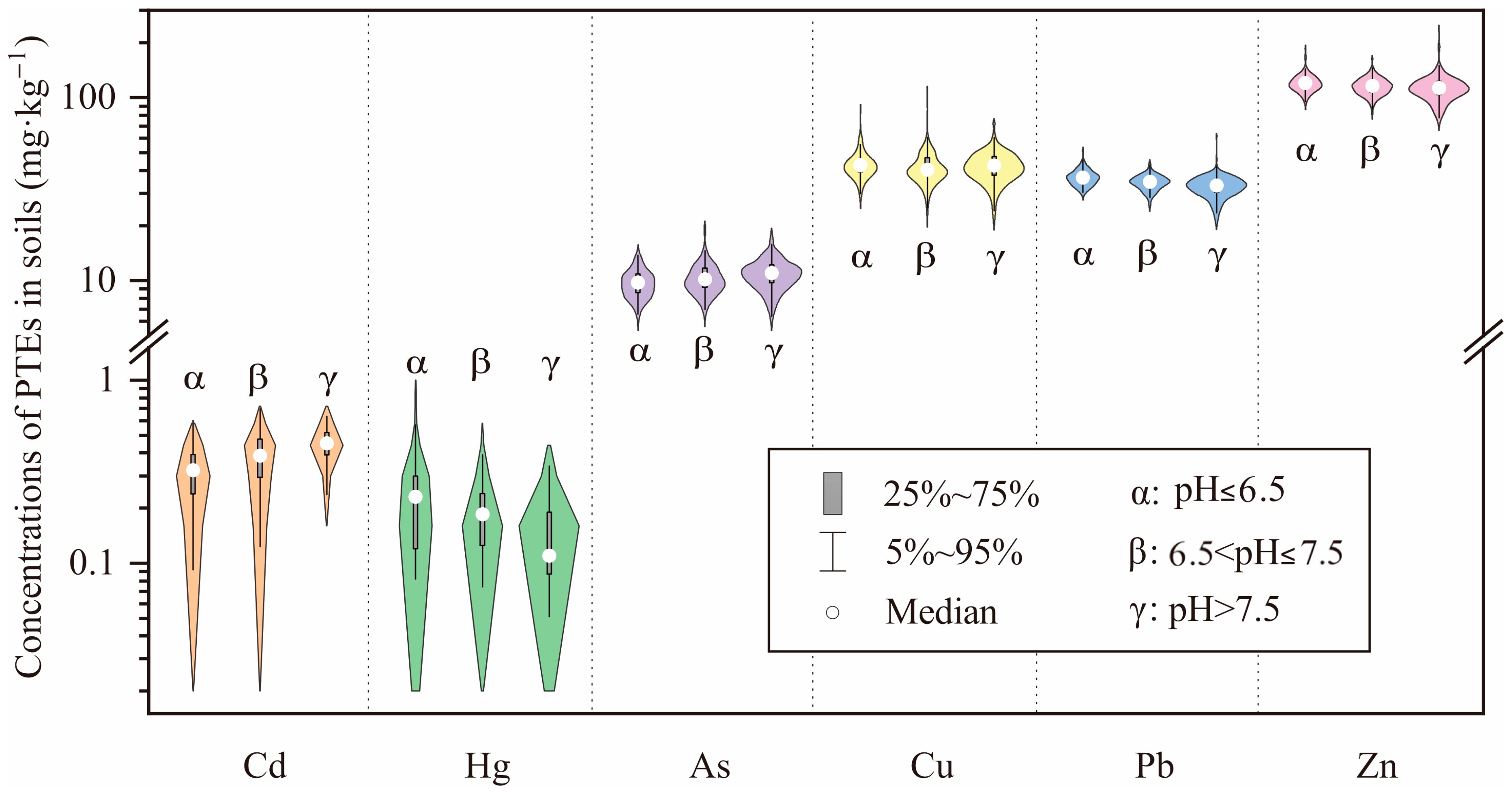

3.1. Heavy Metal Characteristics in Soils

3.2. Evaluation Using Pollution Indices

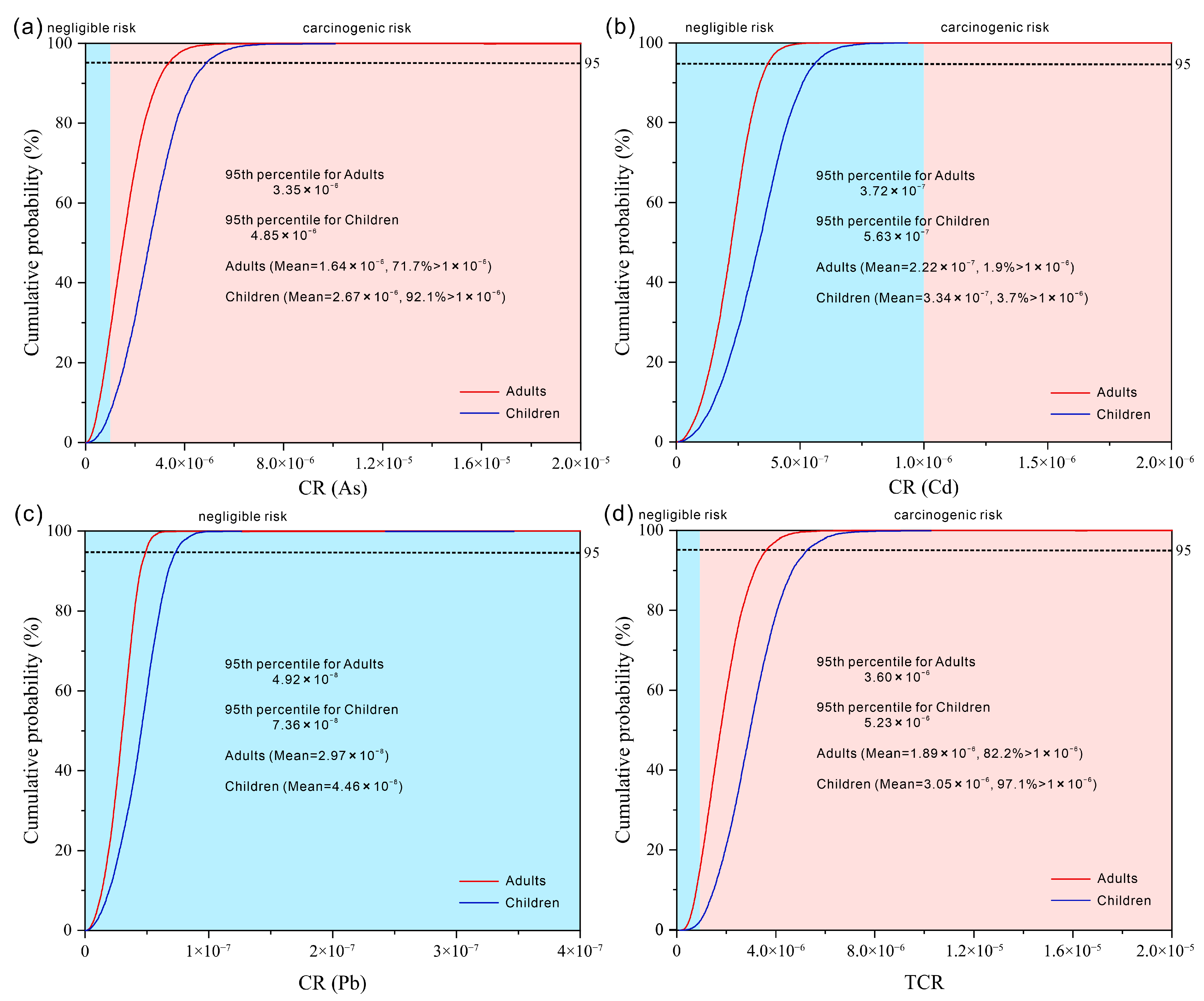

3.3. Probabilistic Risk Modeling

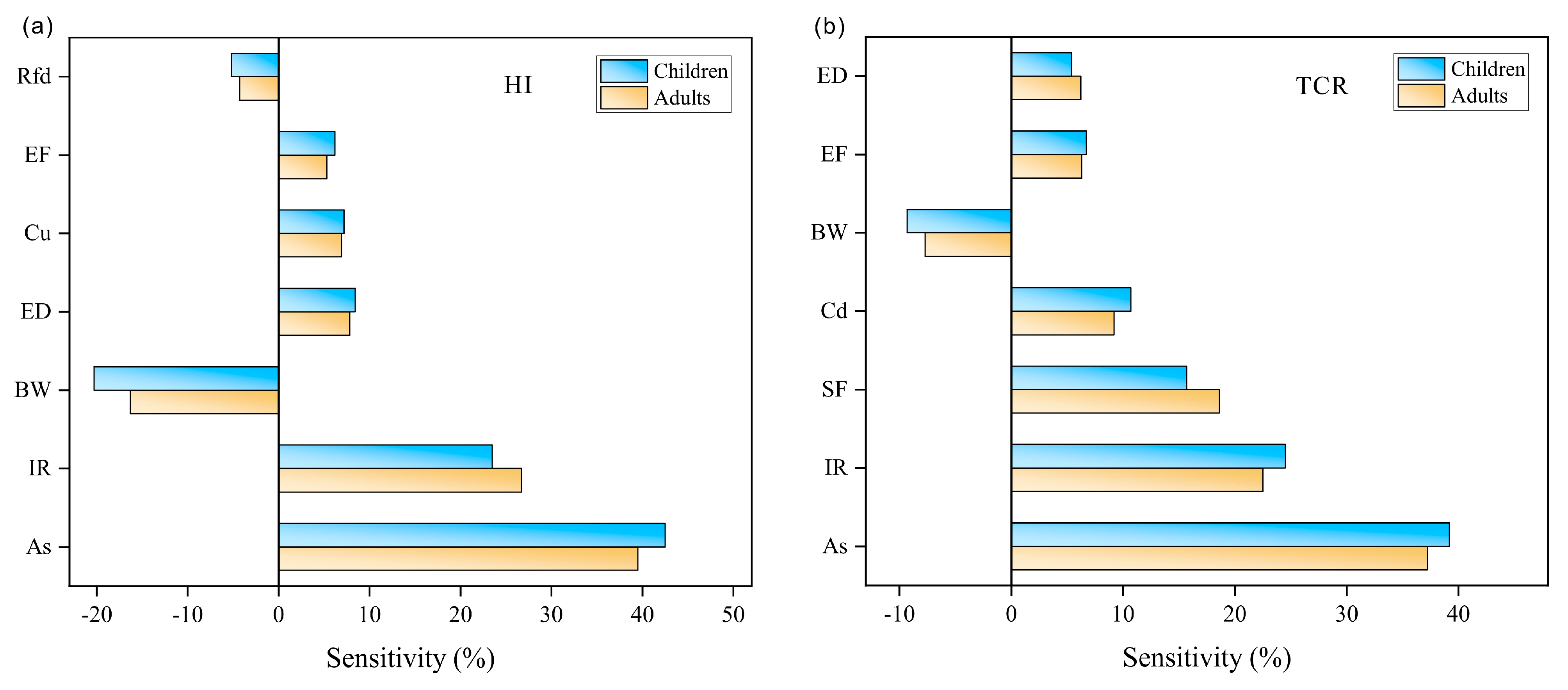

3.4. Sensitivity Analysis

3.5. Risk Management Implications

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- NBSC (National Bureau of Statistics of China). China Statistical Yearbook 2024; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2024. (In Chinese)

- Zhao, F.-J.; Ma, Y.; Zhu, Y.-G.; Tang, Z.; McGrath, S.P. Soil contamination in China: Current status and mitigation strategies. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 750–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Deng, M.; Japenga, J.; Li, T.; Yang, X.; He, Z. Heavy metal pollution and health risk assessment of agricultural soils in a typical peri-urban area in southeast China. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 207, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniadis, V.; Levizou, E.; Shaheen, S.M.; Ok, Y.S.; Sebastian, A.; Baum, C.; Rinklebe, J. Trace elements in the soil-plant interface: Phytoavailability, translocation, and phytoremediation—A review. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2017, 171, 621–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangleben, N.L.; Smith, M.T.; Skibola, C.F. Arsenic immunotoxicity, a review. Environ. Health 2013, 12, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diane, G.D.; Li, Z.; Perry, A.E.; Spencer, S.K.; Jay, G.A.; Karagas, M.R. A population-based case–control study of urinary arsenic species and squamous cell carcinoma in New Hampshire, USA. Environ. Health Perspect. 2013, 121, 1154–1160. [Google Scholar]

- Tóth, G.; Hermann, T.; Da Silva, M.R.; Montanarella, L. Heavy metals in agricultural soils of the European Union with implications for food safety. Environ. Int. 2016, 88, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wei, D.; Zhu, Y.G. An inventory of trace element inputs to agricultural soils in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 2524–2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ji, W.; Wei, N.; Liao, Q.; Huang, D.; Meng, X.; Song, Y. Influencing factors of elevated levels of potentially toxic elements in agricultural soils from typical karst regions of China. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.Z.; Zhu, C.Y.; Gao, J.J.; Cheng, K.; Hao, J.M.; Wang, K.; Hua, S.B.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, J.R. Quantitative assessment of atmospheric emissions of toxic heavy metals from anthropogenic sources in China: Historical trend, spatial distribution, uncertainties, and control policies. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015, 12, 6505–6526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarino, A.; Albanese, S.; Cicchella, D.; Ebrahimi, P.; Dominech, S.; Rita Pacifico, L.; Rofrano, G.; Nicodemo, F.; Pizzolante, A.; Allocca, C.; et al. Factors influencing the bioavailability of some selected elements in the agricultural soil of a geologically varied territory: The Campania region (Italy) case study. Geoderma 2022, 428, 116207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ma, Z.; van der Kuijp, T.J.; Yuan, Z.; Huang, L. A review of soil heavy metal pollution from mines in China: Pollution and health risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 468–469, 843–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Li, Z.; Lu, X.; Duan, Q.; Huang, L.; Bi, J. A review of soil heavy metal pollution from industrial and agricultural regions in China: Pollution characteristics and risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 642, 690–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.; Li, X.; Chen, W. From Total Concentration to Bioaccessible Load: Reassessing Soil Heavy Metal (loid) s Risks Through Probabilistic Exposure Approach and Toxicokinetic Modeling. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 495, 139062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- USEPA (United States Environmental Protection Agency). Exposure Factors Handbook (Final Edition); U.S. Environment Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; EPA/600/R-09/052F.

- Atamaleki, A.; Asadi, Z.S.; Moradinia, M. Quantification and probabilistic health risk assessment of benzene series compounds emitted from cooking process in restaurant kitchens. Build. Environ. 2024, 266, 112100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.L. Exposure Factors Handbook of Chinese Population; China Environmental Press: Beijing, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Malakootian, M.; Mohammadi, A.; Nasiri, A.; Asadi, A.M.S.; Conti, G.O.; Faraji, M. Spatial distribution and correlations among elements in smaller than 75 μm street dust: Ecological and probabilistic health risk assessment. Environ. Geochem. Health 2021, 43, 567–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Z.; Lin, C.; Yang, K.; Cheng, H.; Gu, X.; Wang, B.; Wu, L.; Ma, J. Lability, bioaccessibility, and ecological and health risks of anthropogenic toxic heavy metals in the arid calcareous soil around a nonferrous metal smelting area. Chemosphere 2022, 307, 136200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.; Zhou Jun Lu, B.; Zhang, C.; Li, D.; Zhou Jing Jiao, S.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, H. Environmental and human health risks from cadmium exposure near an active lead-zinc mine and a copper smelter, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 720, 137585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhao, J.; Chang, S.X.; Collins, C.; Xu, J.; Liu, X. Status assessment and probabilistic health risk modeling of metals accumulation in agriculture soils across China: A synthesis. Environ Int. 2019, 128, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IARC (International Agency for Research on Cancer). IARC Monographs on the Identification of Carcinogenic Hazards to Humans. Volume 133: Arsenic, Metals, Fibres, and Dusts; World Health Organization: Lyon, France, 2024; Available online: https://monographs.iarc.who.int/list-of-classifications/ (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Khan, Z.I.; Ahmad, K.; Rehman, S.; Siddique, S.; Bashir, H.; Zafar, A.; De Mastro, G. Health risk assessment of heavy metals in wheat using different water qualities: Implication for human health. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 947–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Wen, Y. Distributions and influencing factors of heavy metals in Soils from Zhenjiang and Yangzhou, China. Minerals 2025, 15, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Liao, J.; Jia, F.; Wen, Y. Characterization of Cd and Pb bioavailability in agricultural soils using DGT technique and DIFS model. Minerals 2025, 15, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Nasir, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, H.; Guo, H.; Lv, J. Comparison of DGT with traditional methods for assessing cadmium bioavailability to Brassica chinensis in different soils. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 14206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, E.K.; Zhou, J.; Yang, X.; Jin, T.; Zhao, B.Q.; Li, L.L.; Wen, Y.C.; Soldatova, E.; Zamanian, K.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; et al. Long-term organic fertilizer-induced carbonate neoformation increases carbon sequestration in soil. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenery, S.R.; Izquierdo, M.; Marzouk, E.; Klinck, B.; Palumbo-Roe, B.; Tye, A.M. Soil-plant interactions and the uptake of Pb at abandoned mining sites in the Rookhope catchment of the N. Pennines, UK-a Pb isotope study. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 433, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurek, R.; Kowalska, J.; Gąsiorek, M.; Zadrożny, P.; Józefowska, A.; Zaleski, T.; Kępka, W.; Tymczuk, M.; Orłowska, K. Assessment of heavy metals contamination in surface layers of Roztocze National Park Forest soils (SE Poland) by indices of pollution. Chemosphere 2016, 168, 839–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CNEMC (China National Environmental Monitoring Centre). The Background Values of Elements in Chinese Soils; China Environmental Science Press: Beijing, China, 1990. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hakanson, L. An ecological risk index for aquatic pollution control. A Sedimentological Approach. Water Res. 1980, 14, 975–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Fernández, A.; González-Muñoz, M.J.; Lobo-Bedmar, M.C. Establishing the importance of human health risk assessment for metals and metalloids in urban environments. Environ. Int. 2014, 72, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez-Andreotta, M.D.; Brusseau, M.L.; Beamer, P.; Maier, R.M. Home gardening near a mining site in an arsenic-endemic region of Arizona: Assessing arsenic exposure dose and risk via ingestion of home garden vegetables, soils, and water. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 454, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Song, Q.; Tang, Y.; Li, W.; Xu, J.; Wu, J.; Brookes, P.C. Human health risk assessment of heavy metals in soil-vegetable system, a multi-medium analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 463, 530–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USEPA (United States Environmental Protection Agency). Regional Screening Levels (RSLs)—Generic Tables. 2019. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/risk/regional-screening-levels-rsls-generic-tables (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- GB-15618-2018; Soil Environmental Quality Risk Control Standard for Soil Contamination of Agricultural Land. MEE (Ministry of Ecology and Environment of China): Beijing, China, 2018.

- Deng, Y.; Ren, C.; Chen, N.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, G.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y. Effects of pH and phosphate on cadmium adsorption onto goethite and a paddy soil: Experiments and NOM-CD model. J. Soil Sediment 2023, 23, 2072–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, S.K.; Scheckel, K.G.; Impellitteri, C.A.; Ryan, J.A. Toxic metals in the environment: Thermodynamic considerations for possible immobilization strategies for Pb, Cd, As, and Hg. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004, 34, 495–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; You, Y.; Bai, Z.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, N. Health risk assessment of personal inhalation exposure to volatile organic compounds in Tianjin, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2011, 409, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orosun, M.M.; Nwabachili, S.; Alshehri, R.F.; Omeje, M.; Alshdoukhi, I.F.; Okoro, H.K.; Ife-Adediran, O. Potentially toxic metals in irrigation water, soil, and vegetables and their health risks using Monte Carlo models. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IRIS (Integrated Risk Information System). IRIS Assessments. 2024. Available online: https://cfpub.epa.gov/ncea/iris2/atoz.cfm (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Zhang, T.; Song, B.; Han, G.; Zhao, H.; Hu, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, H. Effects of coastal wetland reclamation on soil organic carbon, total nitrogen, and total phosphorus in China: A meta-analysis. Land Degrad. Dev. 2023, 34, 3340–3349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lallawmzuali, G.; Devi, A.S.; Thanhmingliana Hriatsaka, V.; Singh, A.P.; Lalhriatpuia, C. Assessment of the heavy metal contaminations of roadside soil in Aizawl, Mizoram (India): An in-depth analysis utilising advanced scientific methodologies. Asian J. Water Environ. Pollut. 2024, 21, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustin, F.; Houle, D.; Gagnon, C.; Courchesne, F. Long-term base cation weathering rates in forested catchments of the Canadian Shield. Geoderma 2015, 247, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Wang, X.; Sun, M.; Liu, H.; Liu, D.; Dai, J. Cadmium immobilization in soil using phosphate modified biochar derived from wheat straw. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 926, 171614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majumdar, A.; Upadhyay, M.K.; Giri, B.; Yadav, P.; Moulick, D.; Sarkar, S.; Roychowdhury, T. Sustainable water management in rice cultivation reduces arsenic contamination, increases productivity, microbial molecular response, and profitability. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 466, 133610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.J.; Wang, P. Arsenic and cadmium accumulation in rice and mitigation strategies. Plant Soil 2020, 446, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| As | Cd | Cu | Hg | Pb | Zn | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <RSV | number | 440 | 75 | 447 | 439 | 441 | 448 |

| percentage | 97.99% | 16.71% | 99.54% | 97.99% | 98.22% | 99.78% | |

| RSV~RIV | number | 9 | 374 | 2 | 10 | 8 | 1 |

| percentage | 2.01% | 83.29% | 0.46% | 2.23% | 1.78% | 0.22 | |

| >RIV | number | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| percentage | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| As | Cd | Cu | Hg | Pb | Zn | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10th | −0.03 | 0.81 | 0.30 | 1.62 | −0.09 | 0.17 |

| 25th | 0.16 | 0.96 | 0.42 | 1.87 | 0.03 | 0.25 |

| Mean | 0.32 | 1.09 | 0.57 | 2.58 | 0.12 | 0.36 |

| Median | 0.32 | 1.13 | 0.55 | 2.57 | 0.13 | 0.37 |

| 75th | 0.49 | 1.20 | 0.73 | 3.15 | 0.23 | 0.47 |

| 90th | 0.66 | 1.35 | 0.88 | 3.61 | 0.30 | 0.55 |

| Class 0 (%) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.10 | 0.00 | 21.40 | 3.60 |

| Class 1 (%) | 92.10 | 26.90 | 94.90 | 0.20 | 78.60 | 95.30 |

| Class 2 (%) | 6.80 | 72.20 | 4.00 | 28.30 | 0.00 | 1.10 |

| Class 3 (%) | 1.10 | 0.90 | 0.00 | 37.90 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Class 4 (%) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 30.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Class 5 (%) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Class 6 (%) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.40 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| As | Cd | Cu | Hg | Pb | Zn | PERI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10th | 7.37 | 79.09 | 9.21 | 184.4 | 7.05 | 1.68 | 312.5 |

| 25th | 8.27 | 87.27 | 10.04 | 220.0 | 7.64 | 1.78 | 359.0 |

| Mean | 9.54 | 97.14 | 11.32 | 419.0 | 8.20 | 1.95 | 547.2 |

| Median | 9.38 | 98.18 | 10.97 | 355.6 | 8.21 | 1.93 | 484.2 |

| 75th | 10.54 | 103.64 | 12.47 | 533.3 | 8.79 | 2.08 | 663.0 |

| 90th | 11.88 | 114.55 | 13.76 | 733.3 | 9.24 | 2.20 | 870.3 |

| Non-Carcinogenic Heavy Metal | Probabilistic Distribution of RfD (mg kg−1 d−1) | Parameters | Carcinogenic Heavy Metal | Probabilistic Distribution of SF (mg kg−1 Day−1)−1 | Parameters | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| As | Triangular | TRI (0.0003, 0.0003, 0.0008) | As | Triangular | TRI (0, 1.5, 1.5) | [35,41] |

| Cd | Triangular | TRI (0.001, 0.001, 0.04) | Cd | Triangular | TRI (0, 6.1, 6.1) | [35,41] |

| Cu | Triangular | TRI (0.04, 0.04, 0.1) | Cu | N/A | N/A | [35,41] |

| Hg | Triangular | TRI (0.0003, 0.0003, 0.001) | Hg | N/A | N/A | [35,41] |

| Pb | N/A | N/A | Pb | Triangular | TRI (0, 0.0085, 0.0085) | [35,41] |

| Zn | Triangular | TRI (0.3, 0.3, 0.91) | Zn | N/A | N/A | [35,41] |

| Exposure Factor | Symbol (Unit) | Probabilistic Distribution | Parameter: UN (Minimum, Maximum); LN (Mean, SD); TRI (Minimum, Likeliest, Maximum) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight | BW (kg) | Uniform (adults) | UN (55.683, 68.6) | [17] |

| Lognormal (children) | LN (37.0, 2.98) | |||

| Oral ingestion rate of soils | IRO (mg day−1) | Triangular (adults) | TRI (4, 30, 52) | [15] |

| Triangular (children) | TRI (66, 103, 161) |

| Parameter | Description | Unit | Value | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EF | Exposure frequency | day year−1 | 350 | [15] |

| ED | Exposure duration | year | 24 for adults and 6 for children | [15] |

| AT | Average time | day | ED × 365 for non-carcinogenic heavy metals and 70 × 365 for carcinogenic heavy metals | [15] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ji, W.; Wu, S.; Gong, Y.; Meng, X. Pollution Levels and Associated Health Risks of Heavy Metals in Agricultural Soils in Zhenjiang and Yangzhou, China. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2552. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242552

Wen Y, Wang Y, Ji W, Wu S, Gong Y, Meng X. Pollution Levels and Associated Health Risks of Heavy Metals in Agricultural Soils in Zhenjiang and Yangzhou, China. Agriculture. 2025; 15(24):2552. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242552

Chicago/Turabian StyleWen, Yubo, Yuanyuan Wang, Wenbing Ji, Shengmin Wu, Yang Gong, and Xianqiang Meng. 2025. "Pollution Levels and Associated Health Risks of Heavy Metals in Agricultural Soils in Zhenjiang and Yangzhou, China" Agriculture 15, no. 24: 2552. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242552

APA StyleWen, Y., Wang, Y., Ji, W., Wu, S., Gong, Y., & Meng, X. (2025). Pollution Levels and Associated Health Risks of Heavy Metals in Agricultural Soils in Zhenjiang and Yangzhou, China. Agriculture, 15(24), 2552. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242552