3.1. Scenario Description

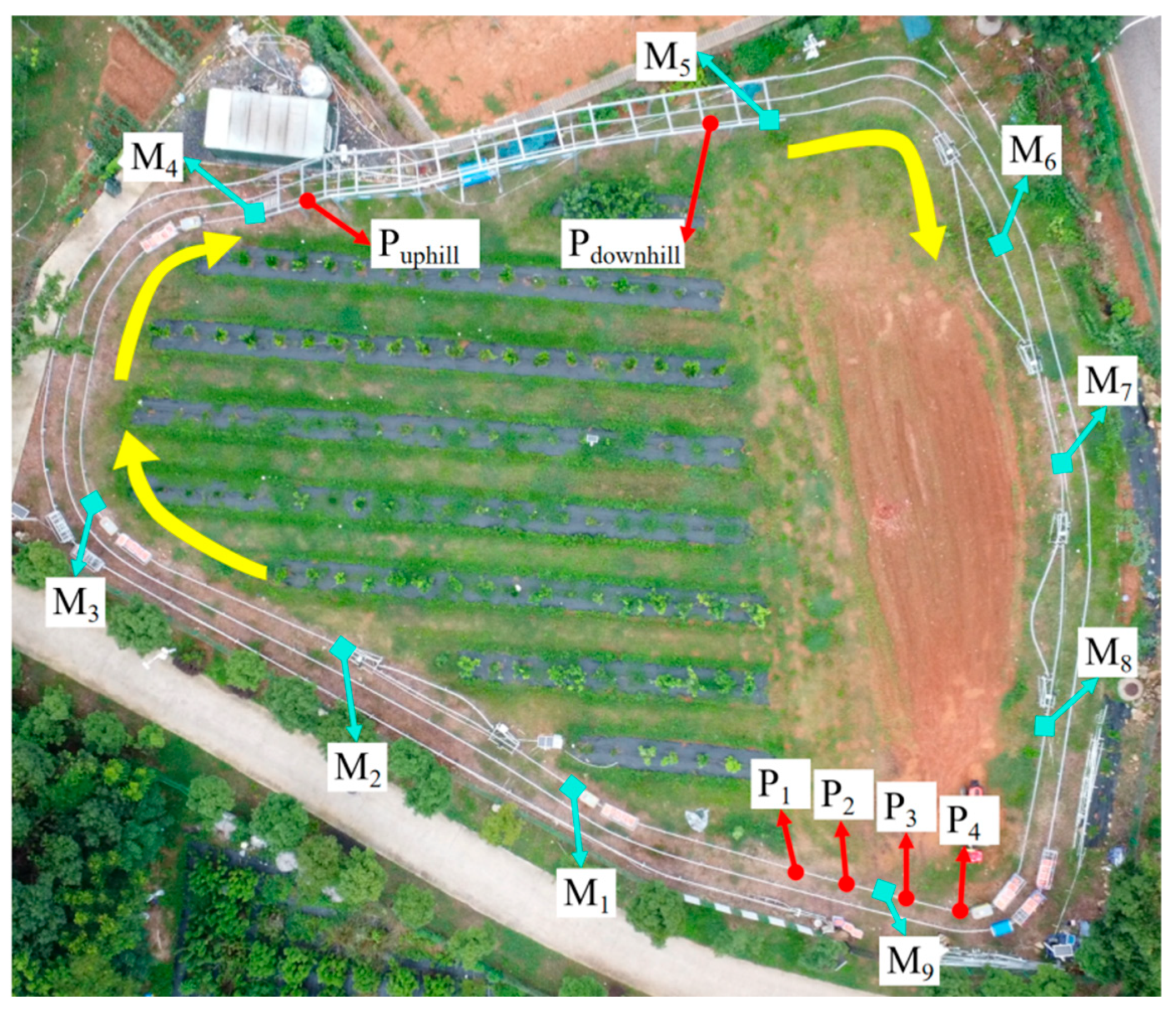

The hilly orchard rail transport system is well-suited to areas characterised by significant topographical variations and high transportation demands. It is utilised in the central and southern hilly orchards of China for the transportation of harvested fruits and agricultural equipment.

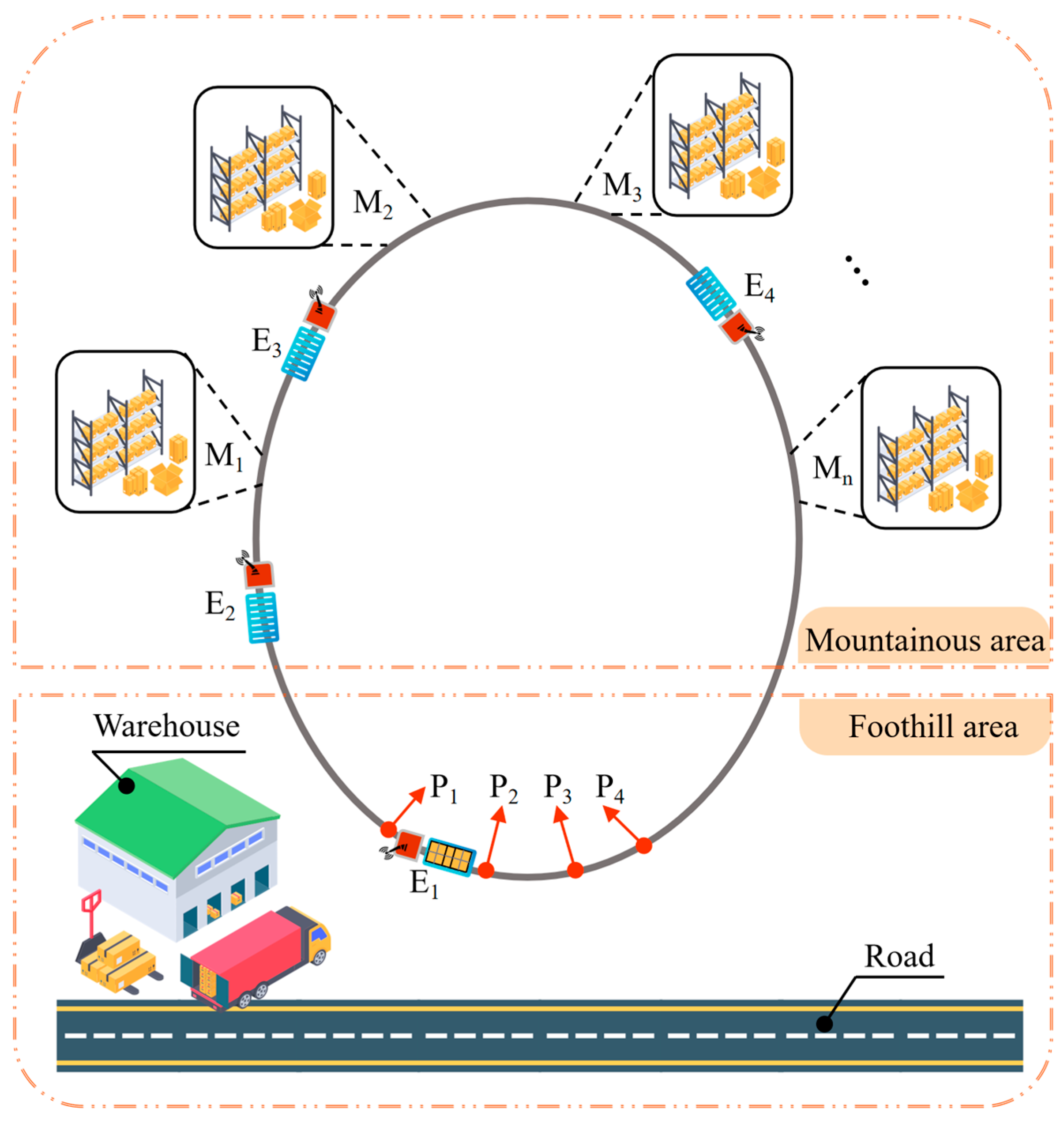

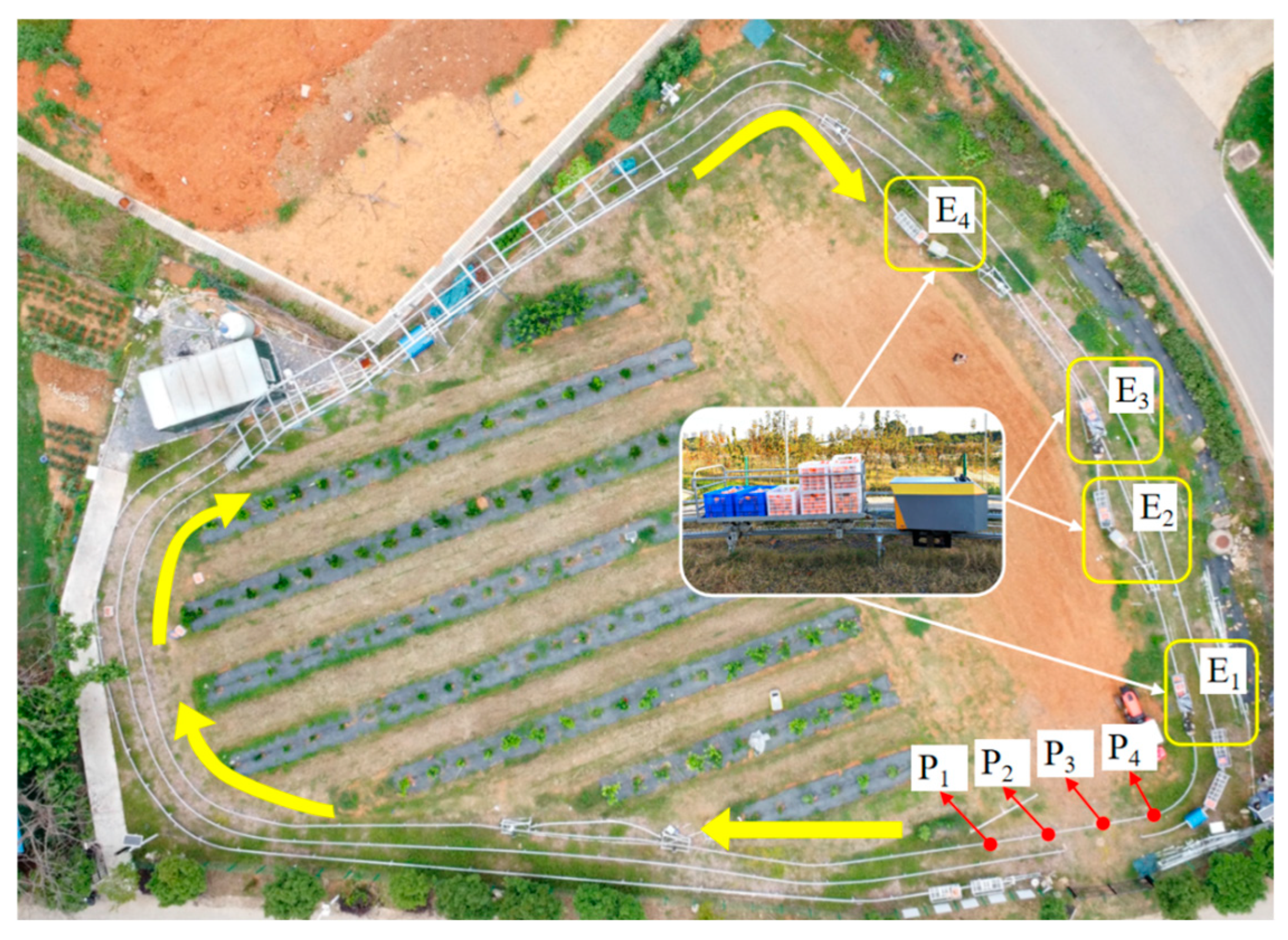

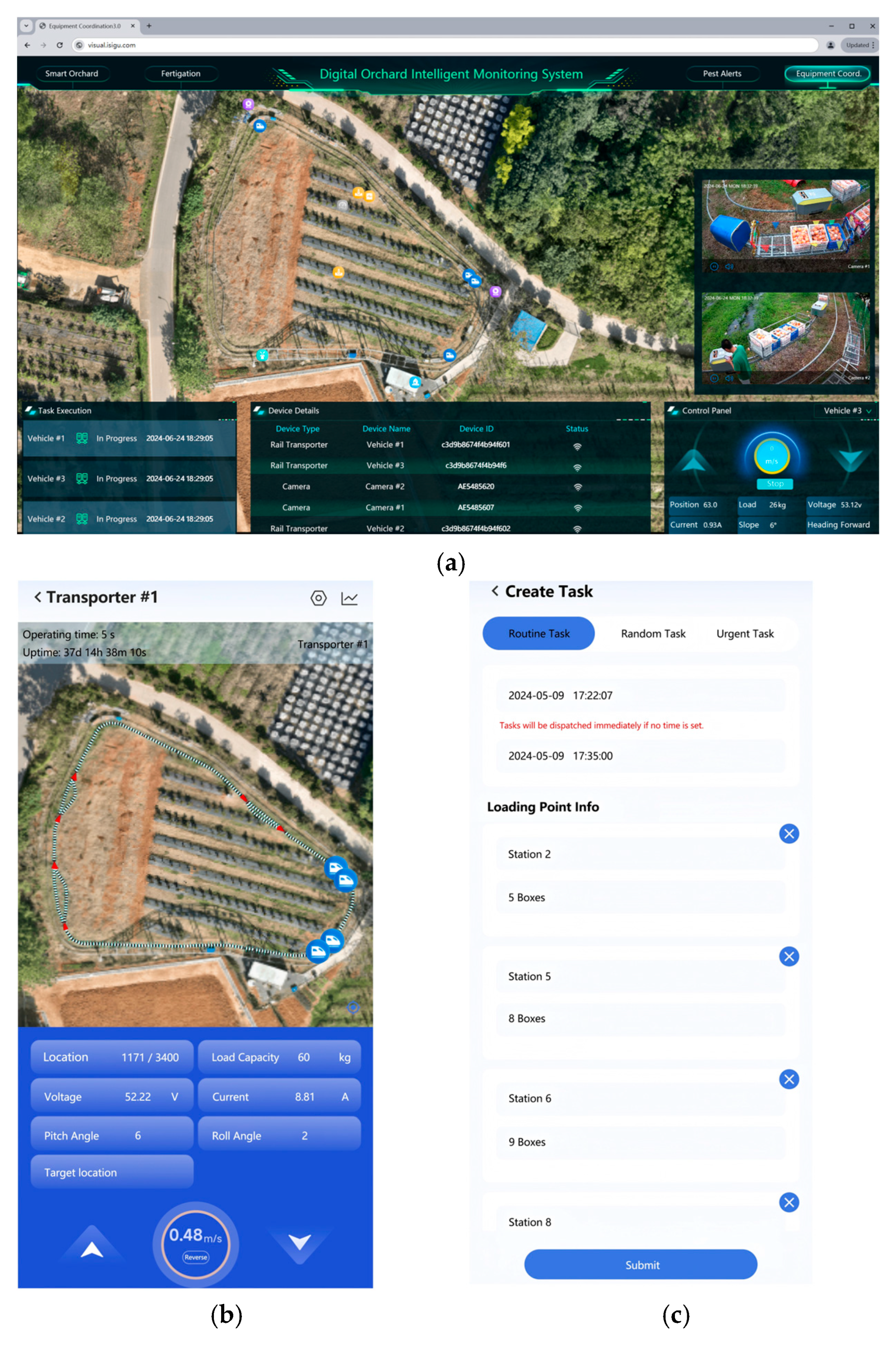

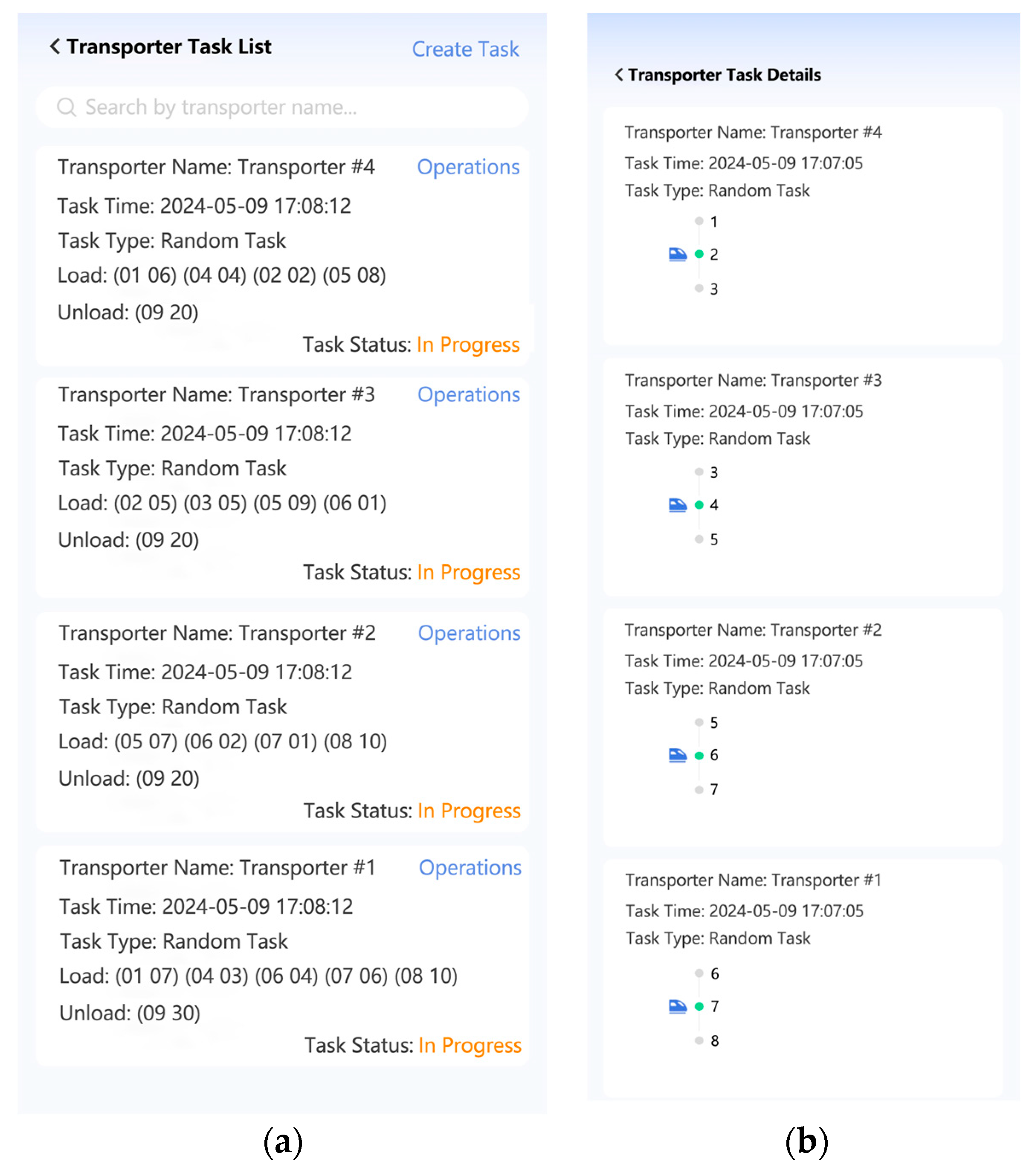

Figure 1 presents a prototype of the hilly orchard rail transport system.

The focus of this paper is the fruit harvesting period, during which the proposed transport system integrates individual transporters into a unified scheduling network designed for high-efficiency orchard logistics. The system operates on several core principles to address the complex terrain. First, unlike battery-powered alternatives with limited range, the transporters utilize a sliding contact line power supply technology [

24] to enable continuous operation without charging interruptions, which is critical for maintaining system-level throughput. Second, to ensure safety and simplify control, the system enforces a unidirectional clockwise flow on the closed-loop track. Crucially, this configuration facilitates an inter-vehicle collision avoidance mechanism, where transporters maintain safe separation distances based on their real-time on-track positions.

In terms of logistics, the layout is designed with multiple distributed loading points (M

1–M

n) converging to a single unloading station near the base, reflecting a typical ‘field-to-warehouse’ pattern where agricultural equipment is non-consumable and circulates between tasks. Furthermore, to enable intelligent coordination, each transporter is equipped with onboard controllers (Orange Pi 5 Pro, Shenzhen Xunlong Software Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China), position sensors (JY-L8900 RFID Reader, Guangzhou Jianyong Information Technology Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, China), load cells (DYLY-102, Bengbu Dayang Sensor System Engineering Co., Ltd., Bengbu, China), and wireless modules (LTE Module Air780E, Shanghai AirM2M Communication Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) that report real-time status to a central server for dynamic task allocation. For specific mechanical designs of the transporters and detailed system-level field configurations, please refer to Reference [

24] and

Appendix D, respectively. The overall schematic layout is depicted in

Figure 2.

The research was conducted through a series of targeted experimental sessions from May 2023 to October 2025. This extended period allowed for an iterative development process comprising two primary phases: (1) System Characterization (May–October 2023): Initial physical trials were performed to measure foundational operational parameters, including transporter speeds under varying loads and standard dwell times. These real-world measurements were essential for calibrating the simulation environment to ensure fidelity. (2) Algorithm Evolution and Hybrid Validation (2024–2025): This phase involved the parallel development of scheduling algorithms and their validation. We first established the simulation platform to train and comprehensively compare the proposed algorithm suite, including DQN, MARL-DQN, and SAC, using realistic task configurations (detailed in

Section 4.1.1). Subsequently, intermittent field validation campaigns were conducted on the 153 m experimental track. In these trials, the DQN algorithm was deployed as the representative baseline to verify the feasibility of the RL-based control strategies and to validate the consistency between simulation predictions and physical system behavior, as detailed in

Section 4.5 and

Appendix D.

3.2. Model Assumptions and Formula Derivation

The basic prerequisites for completing transport tasks include the performance parameters of the transporters, operational environments, and task parameters. This paper is based on the actual operating conditions of hilly orchard track transport systems and considers constraints related to circular RGV systems. The following assumptions have been made:

The initial spacing between each transporter equals the length of the transporter plus a minimum safety distance.

The transporters operate unidirectionally on a closed track exclusively in a clockwise direction, without any allowance for reversing or overtaking; they are also sequentially numbered in descending order following the clockwise direction.

The locations of the task points and the existing task quantities are known. Task points are numbered in a clockwise direction starting from the initial position, with higher numbers indicating longer travel times from the initial position.

Transporters are assumed to travel at a constant speed throughout the journey, with a fixed maximum load capacity. Additionally, all transporters are of the same model with identical performance parameters.

In simulations, the position of the transporter is indirectly calculated using time and operational parameters.

Upon reaching any task point, transporters can immediately begin loading or unloading to ensure operational efficiency, with only one transporter allowed to operate at each task point at any time.

The dwell time at each loading point is the same for all transporters, regardless of the load amount, meaning more loading activities will increase the duration needed to complete the tasks.

During each transport cycle, each transporter can stop at multiple task points as per its maximum load capacity, but the total amount transported must not exceed this limit.

If the distance between adjacent transporters falls below the minimum safety distance, the following transporter will stop moving.

The derivation of the total task completion time for the transport system is as follows:

Multiple loading points are set along the track, collectively defined as , where n is the number of task points. There is only one storage point (unloading point), denoted as . The set of current task quantities required at each task point is denoted as . The set of transporters on the track is , where c is the number of transporters. Each transporter’s load capacity is denoted as , in boxes. The smallest set of tasks generated is , where num is the minimum number of tasks. The number of trips is denoted as .

As shown in Equation (1),

represents the time taken for

c transporters to complete the

t-th trip, as calculated in Equations (2)–(4). Assuming that

c transporters work simultaneously and in parallel to complete tasks, the completion time

for each trip is the maximum of the individual completion times

for each transporter

where

is the response time from task issuance to the transporter’s start of execution, measured in seconds;

represents the active time required to complete a trip task, also measured in seconds;

and

denote the loading and unloading times, respectively, with

measured in seconds and

indicating the number of loadings, and

is the unloading time in seconds, with

representing the number of unloadings, set as a constant of 1 for this study;

describes the waiting time due to road congestion during task execution, in seconds, with

counting the number of stops due to congestion; and

refers to the travel time of the transporters during task execution, measured in seconds, with

counting the number of travel instances.

3.3. Model Establishment

3.3.1. Description of Dynamic Events

In the hilly orchard track transport system, dynamic scheduling is a key strategy for addressing constantly changing tasks. Unlike static scheduling, it can respond in real time to dynamic and emergency tasks [

38], significantly enhancing system flexibility and efficiency. The system mainly faces two types of dynamic events: task disturbances and resource disturbances [

39]. Task disturbances involve the random arrival of tasks and the handling of urgent tasks. During the fruit harvest season, the timing and quantity of fruit arrivals vary dynamically, making static scheduling insufficient. Additionally, emergency transport tasks for agricultural equipment often take a higher priority, requiring the scheduling system to quickly reallocate resources. Resource disturbances include transporter malfunctions or track congestion. To prevent such issues, all transporters undergo thorough debugging before starting tasks. Therefore, this model primarily focuses on task disturbances. Dynamic scheduling must handle urgent tasks while ensuring the smooth transport of regular goods. The scheduling method should flexibly manage the random arrival of tasks and adjust in real time to accommodate emergencies, enabling the transport system to operate efficiently under various conditions.

3.3.2. Rescheduling Methods

In the hilly and mountainous orchard rail transport system, dynamic scheduling faces the challenge of managing tasks with multiple loading points and a single unloading point. New tasks are constantly generated during transport. Rescheduling is crucial for addressing these issues by clearly defining specific operational procedures, including application positions, strategies, and timing of the scheduling algorithm.

Rescheduling should take place at designated spots where the transporter is stationary and its location is fixed. The transporter’s location varies significantly while moving but is more easily determined when stopped, especially at preset loading and unloading points. Before each task begins, the transporter is dispatched from its initial position, which also serves as the unloading and task assignment point. After receiving tasks at this initial position, the transporter proceeds to the targeted loading point to load cargo. This design considers targeted loading points as potential rescheduling locations, facilitating adjustments to the original scheduling plan based on environmental parameters. Thus, rescheduling locations include the initial position and any cargo loading points.

- 2.

Rescheduling Strategies

Rescheduling strategies are categorised into two types: event-driven and period-driven. Event-driven scheduling is initiated by specific events, such as the availability of a transporter at the initial position and the presence of pending tasks at a task point. Decisions to deploy transporters are based on the match between the number of tasks and the availability of transporters. Period-driven scheduling is conducted at set intervals, typically starting with the deployment of one transporter at the beginning of each period, followed by subsequent transporters dispatched at fixed intervals. During the first cycle, multiple transporters may be dispatched simultaneously. As tasks progress, subsequent rescheduling usually involves only one transporter, ensuring continuity and efficiency.

- 3.

Rescheduling Parameters

In dynamic scheduling, tasks arrive randomly, leading to a gradual increase in the quantity of tasks at each point. As the transporter moves from its initial position to the targeted loading points, the quantity of tasks continually changes. Therefore, it is important to determine two key parameters: the number of each loading point and the cargo quantity corresponding to each loading point. These parameters are essential components of the transporter’s scheduling plan. If rescheduling is limited to the initial position, the scheduling algorithm must establish all loading point numbers and their corresponding cargo quantities before departure. If rescheduling includes other task stop points, it is possible to plan future loading point numbers and cargo quantities in advance. For the current loading point, the cargo quantity may be adjusted based on specific conditions to optimise loading efficiency. Consequently, the main dynamic rescheduling parameters include the loading point numbers and their corresponding cargo quantities.

3.3.3. Establishing the Objective Function and Constraints

The primary challenge in dynamic scheduling is the uncertainty of task arrival times, which prevents ensuring that each transporter is always fully loaded. Therefore, while the load rate is an important performance indicator, it cannot serve as a constraint in dynamic scheduling but only as a target for optimisation. The formula to calculate the load rate, ω, is given by:

In this equation, refers to the total task quantity at all points at the end of the tasks, measured in boxes; is the load capacity of a single transporter, also in boxes; is the total number of transporters required to complete all tasks, counted in transporters. The ceiling brackets ⌈ ⌉ are used to round up the result of to the nearest higher integer, which determines the minimum number of transporters needed. represents the actual number of transporters used.

Dynamic scheduling is time-oriented and simulates the entire transport process. The total task completion time, , is determined by the time the last transporter returns to the initial position and is influenced by the number of loading operations, occurrences of congestion, and the departure time of the last transporter. Furthermore, dynamic scheduling allows for rescheduling of loading quantities at loading points to adapt to the arrival of new tasks and changes in existing task quantities. To minimise the instances of transporters stopping at loading points with no tasks, a performance metric n0 is introduced to represent the minimum number of transporter visits to empty task points. This metric has direct practical significance, as each empty stop wastes energy, increases mechanical wear on the braking and starting systems, and extends overall task completion time, thereby reducing operational efficiency. Therefore, the objective function for dynamic scheduling considers the maximum load rate ω, the shortest total task completion time Ttask, and the minimum visits to empty task points n0.

These targets reflect the impact of rescheduling methods, scheduling algorithm performance, and the rate of task generation. The load rate is the most crucial performance indicator, followed by the total task completion time, and finally, the number of transporter visits to empty task points is considered when the first two metrics are comparable.

The objective function for the dynamic scheduling model is:

where

ω is maximized (equivalently, −

ω is minimized),

Ttask is minimized, and

n0 is minimized. The load rate is the most crucial performance indicator, followed by the total task completion time, and finally, the number of transporter visits to empty task points.

The constraints are as follows:

- (1)

The task quantity at each point must be completed entirely but not redundantly.

- (2)

In the actual system, the sequence of transporter positions cannot be altered; hence, in the simulated transport process, the arrival time of any transporter at any position cannot be earlier than those who started later.

3.4. Dynamic Scheduling Methodology

To effectively address the dynamic arrival of tasks within the hilly orchard environment, our methodology proceeds in two distinct stages. First, we establish an optimal foundational scheduling structure by conducting a comparative evaluation of several candidate frameworks. Second, operating within this selected structure, we perform an extensive comparative analysis to identify promising approaches for the decision-making algorithm for the problem at hand.

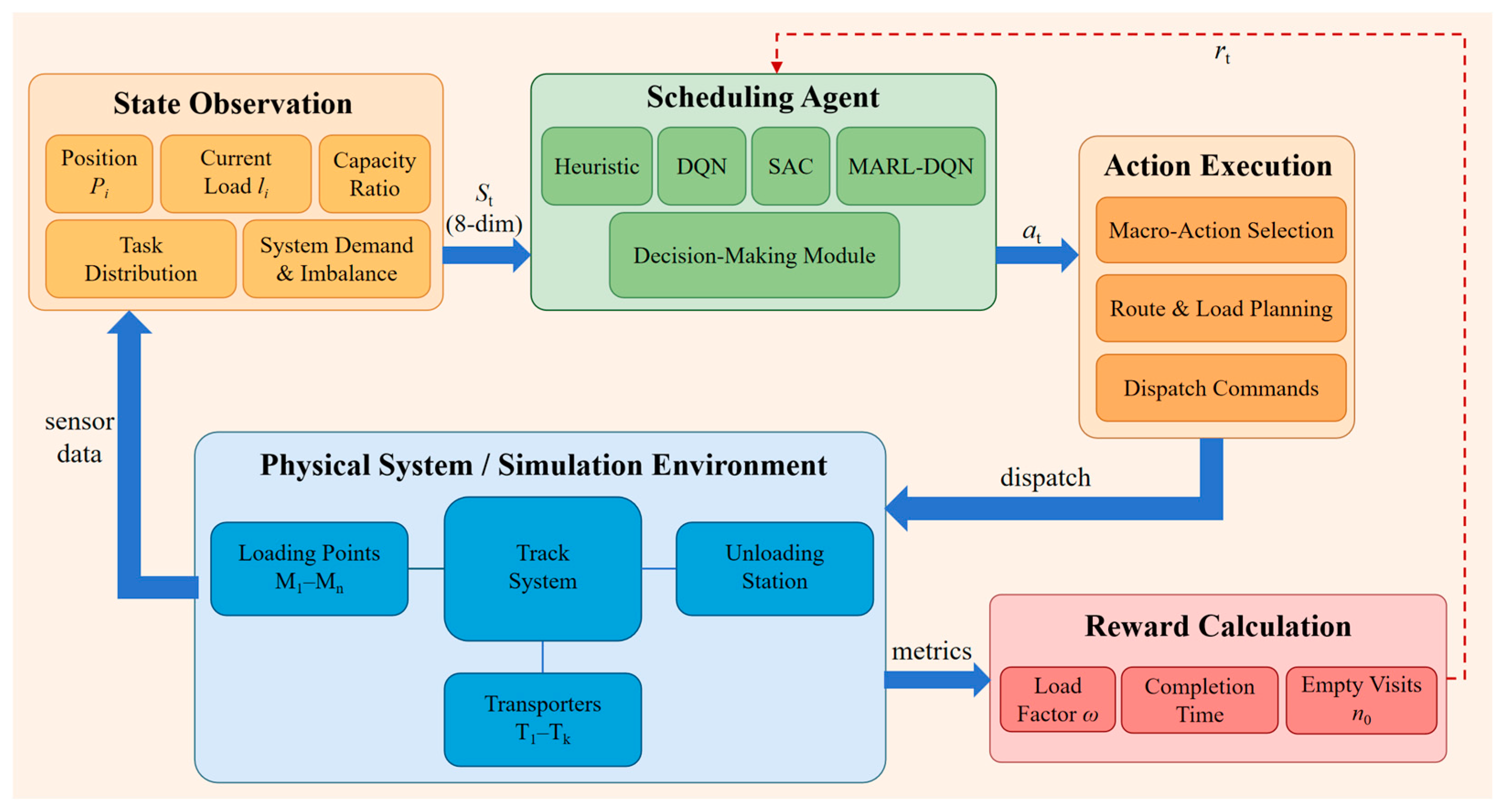

To provide a holistic view of the interaction between these stages,

Figure 3 presents the system architecture of the proposed dynamic scheduling framework, illustrating the closed-loop data flow among five functional modules. The workflow initiates in the Physical System/Simulation Environment (Blue Block), which represents the hilly orchard track system and generates real-time sensor data. This raw data is aggregated by the State Observation (Yellow Block) module into a structured 8-dimensional state vector (

St), encompassing key variables such as transporter position (

Pi), current load (

li), capacity ratio, and system-wide demand imbalance. Acting as the decision-making core, the Scheduling Agent (Green Block) receives this state input and selects an optimal policy using candidate algorithms (Heuristic, DQN, SAC, or MARL-DQN). The resulting policy decision is translated by the Action Execution (Orange Block) module into physical operations, handling macro-action selection, route planning, and dispatch command issuance. Finally, primarily during the training phase, the Reward Calculation (Red Block) module evaluates performance metrics, including load factor (

ω), completion time, and empty visits (

n0), to generate a reward signal (

rt) that updates the agent’s policy, completing the feedback loop.

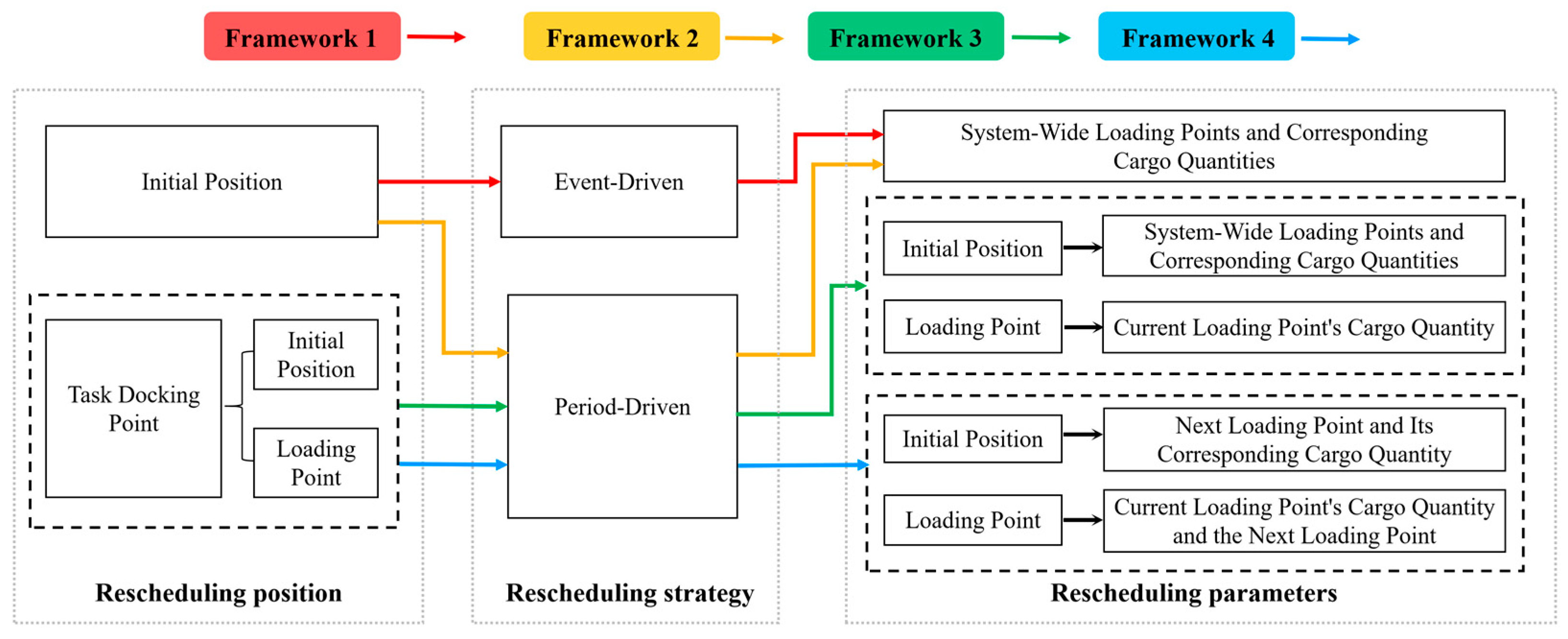

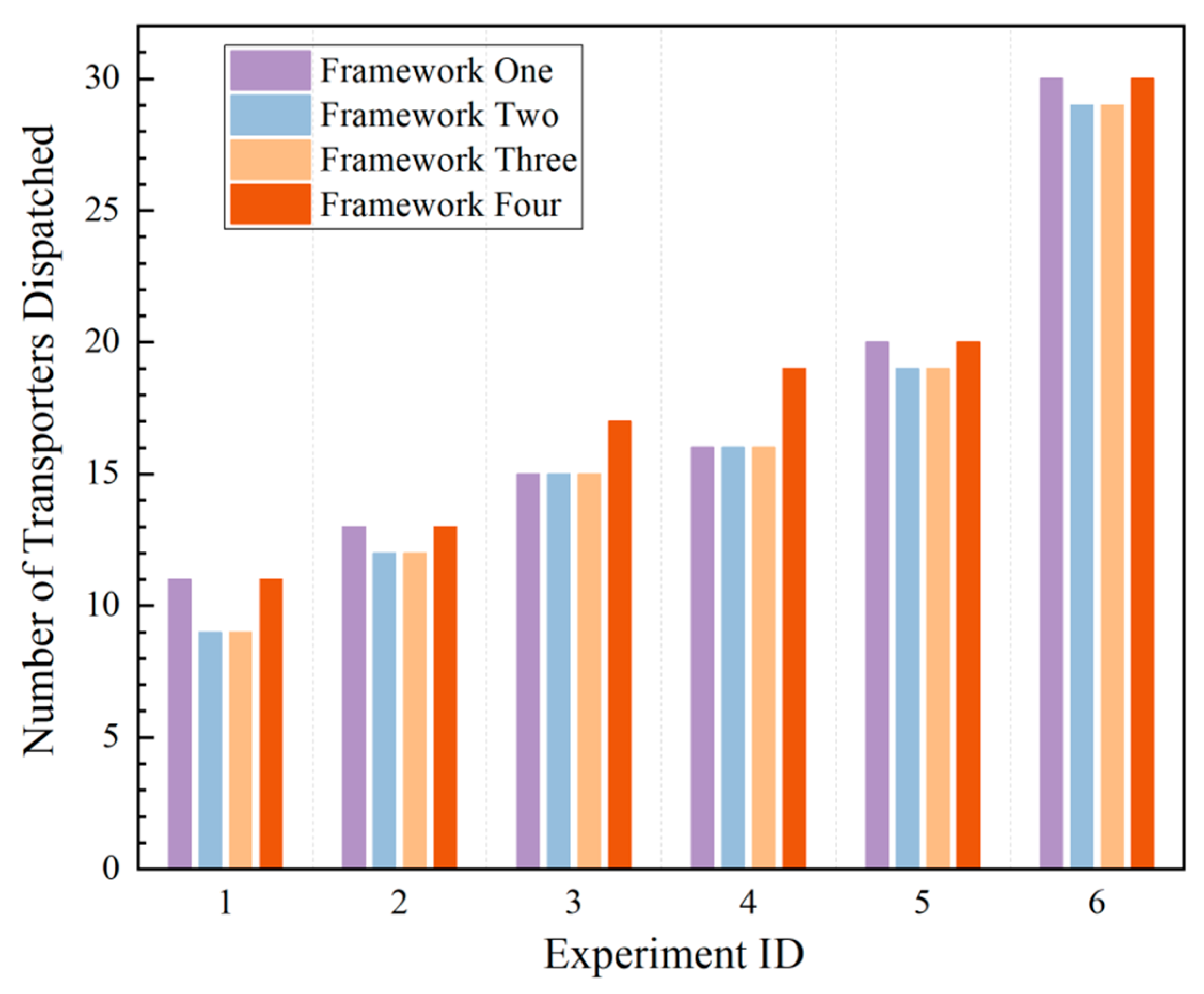

3.4.1. Framework Design

The proposed frameworks are each constructed from three core components: Rescheduling Position, Rescheduling Strategy, and Rescheduling Parameters. As illustrated in

Figure 4, these frameworks are systematically differentiated across these three design dimensions. The diagram utilizes color-coded arrows to map the specific operational structure of each framework, visually highlighting the architectural differences through a feature-by-feature comparison detailed in

Table 1. For a complete technical breakdown of all four frameworks, including detailed flowcharts and corresponding pseudocode, please refer to

Appendix A (

Figure A1,

Figure A2,

Figure A3 and

Figure A4 and Algorithms A1–A4, respectively). As will be quantitatively demonstrated in the experimental results (

Section 4.2), preliminary analysis revealed that Framework 3 provides the optimal performance trade-off. Consequently, it was selected as the foundational platform for the in-depth algorithmic comparisons central to this study.

3.4.2. Action Space Design: A Heuristic Rule Set as Macro-Actions

To enable the reinforcement learning agents to focus on high-level strategic decision-making rather than low-level micro-operations, we designed a discrete action space composed of six heuristic rules. This “Macro-Action” design philosophy is a core component of our methodology. It abstracts the complex decision-making problem into a higher-level strategic choice: “Given the current system state, which scheduling policy is most efficient?” This approach not only significantly reduces the exploration difficulty for the learning algorithm but also serves as a powerful method for embedding domain knowledge into the RL framework.

These six heuristic rules are designed to encapsulate four distinct, widely applied priority concepts in scheduling, aiming to explore solutions from different dimensions:

Position-based Priority (Rules 1–2): The core of these rules is route optimization. They make decisions based on the physical location of task points, such as prioritizing those farthest from or closest to the origin, intending to minimize the transporter’s total travel distance.

Task Quantity-based Priority (Rules 3–4): These rules are a direct embodiment of a greedy strategy. They always prioritize task points with the largest current backlog of goods, representing the most intuitive policy for rapidly clearing system-wide tasks.

Historical Fairness-based Priority (Rule 5): This rule introduces a temporal dimension. It prioritizes task points that have been visited least frequently, aiming to prevent the long-term neglect of certain points due to uneven resource allocation and thus improving overall system fairness and responsiveness.

Future Trend-based Priority (Rule 6): This rule introduces a predictive perspective. It prioritizes serving “hot” task points with the highest average task generation rate, aiming to proactively manage and control task growth at its source to maintain long-term system stability.

By learning to dynamically combine and switch between these macro-actions, which represent different scheduling philosophies, the reinforcement learning agent is expected to discover a superior, adaptive high-level policy that surpasses any single fixed rule. The specific implementation steps for these six rules are detailed in

Appendix B.

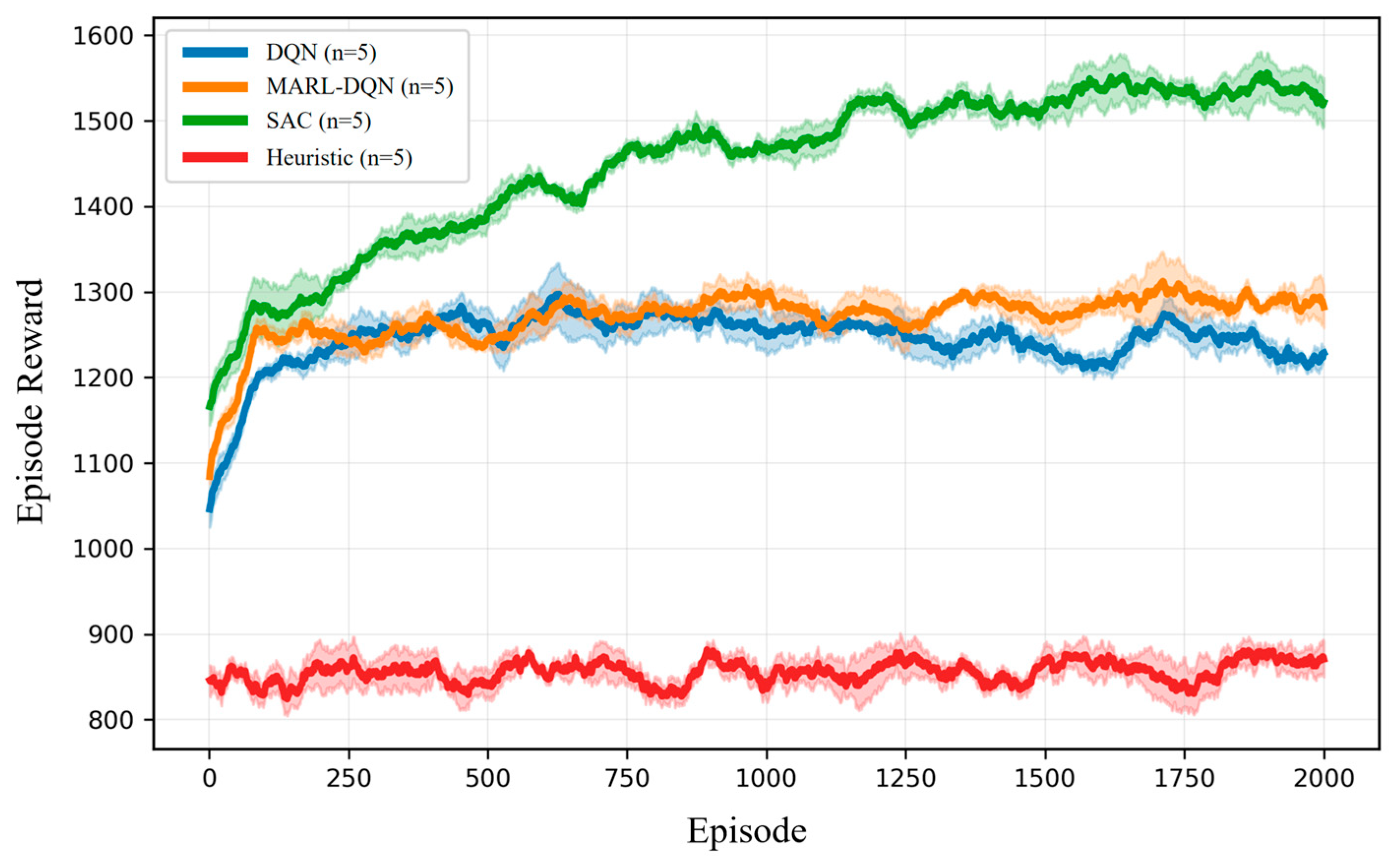

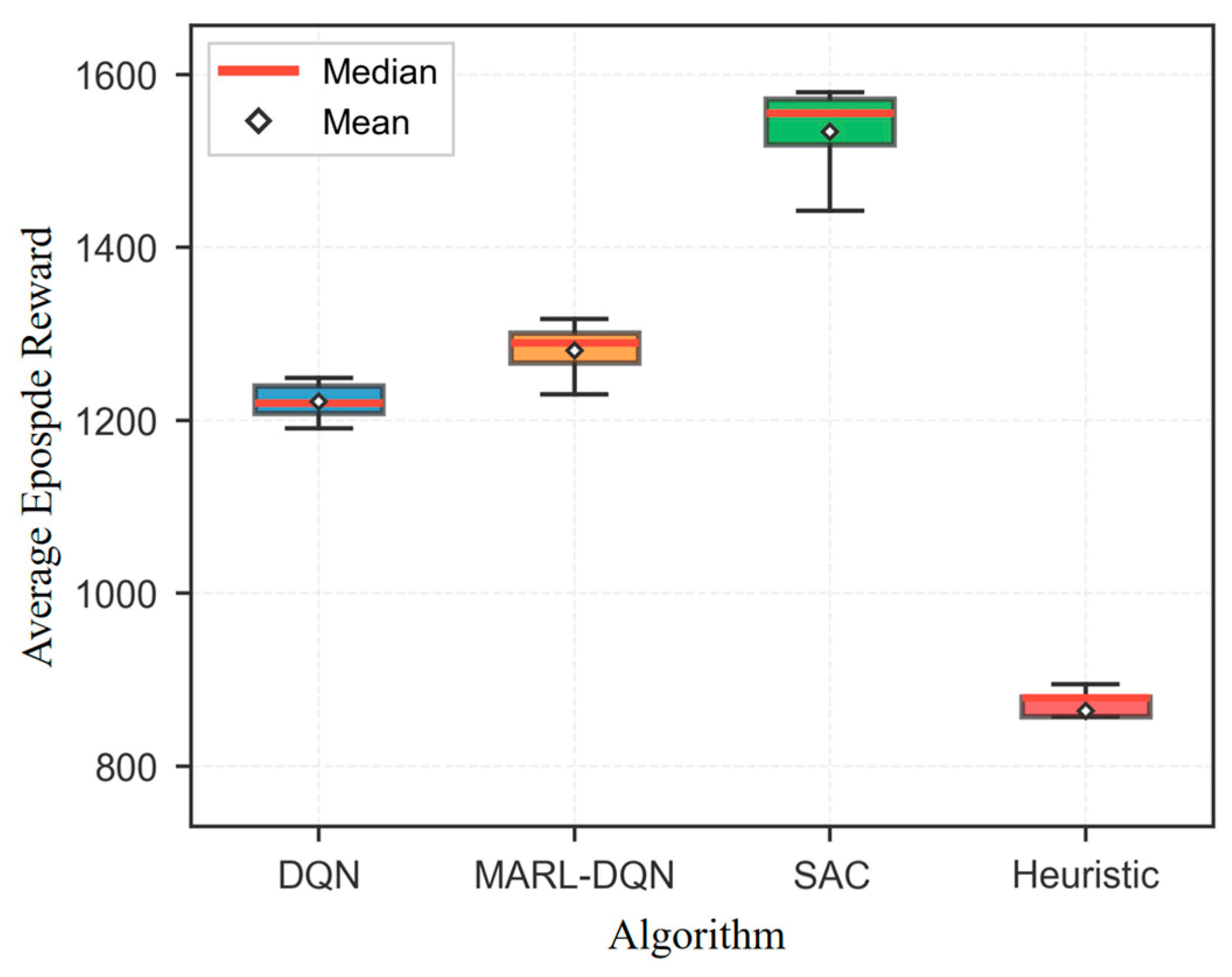

3.4.3. Comparative Algorithm Design: A Duel of Decision-Making Paradigms

Having established the optimal scheduling platform (Framework 3) and defined a common macro-action space, this study aims to systematically evaluate a core scientific question: which decision-making paradigm can most effectively learn and utilize this action space? To this end, we designed and implemented a comparative experimental framework encompassing four representative methodologies. This framework is intended to rigorously investigate the performance trade-offs of different computational intelligence paradigms in solving complex dynamic scheduling problems through empirical research.

To establish a reliable performance benchmark for non-learning methods, we selected the “Prioritise by Task Quantity” rule from the set defined in

Section 3.4.2. This rule represents a direct, traditional scheduling philosophy with extremely low computational cost. Its performance serves as a reference point to measure the effectiveness of all subsequent learning-based algorithms.

- 2.

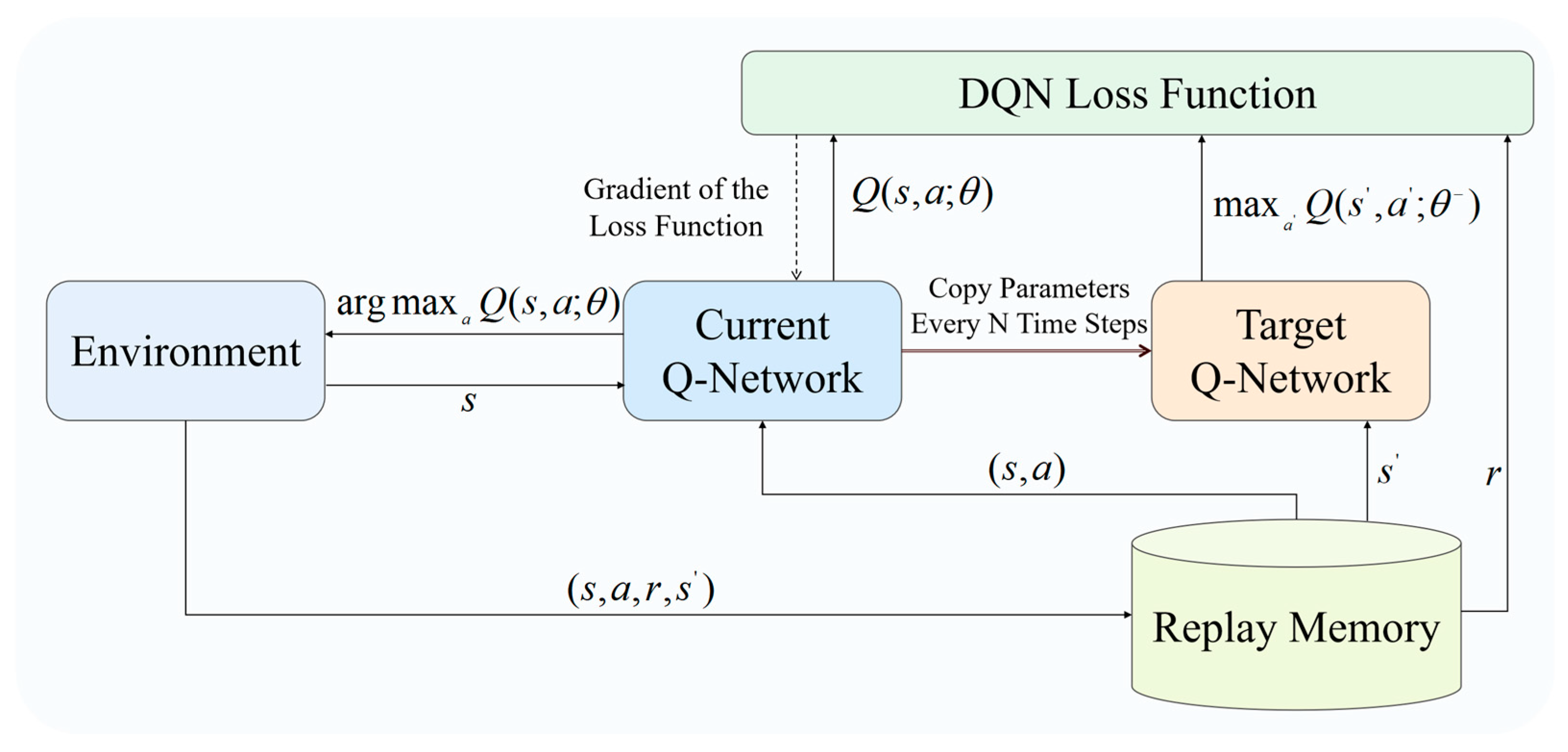

Conventional Single-Agent Baseline: Deep Q-Network (DQN)

To introduce learning capabilities, we first implemented the classic DQN algorithm [

40] as a conventional reinforcement learning baseline. In this configuration, the entire multi-transporter system is treated as a single macroscopic entity, controlled by one central DQN agent. This agent receives the global state of the entire system (detailed in

Section 3.4.4) and selects one of the six macro-actions defined in

Section 3.4.2.

Figure 5 illustrates the DQN architecture. The agent observes the environment state

s, selects an action

a via its Q-network, and the environment returns a reward

r and a new state

s’. This transition (

s,

a,

r,

s’) is stored in the experience replay memory. During training, batches are sampled from this memory to update the network parameters.

- 3.

Decentralized Paradigm: Multi-Agent DQN (MARL-DQN)

To more realistically capture the operation of multiple transporters as independent decision-making units, we implemented a Multi-Agent Deep Q-Network (MARL-DQN) as the decentralized paradigm, illustrated in

Figure 6. Unlike the conventional DQN, which amalgamates all vehicles into a single entity, MARL-DQN adopts the “Centralized Training with Decentralized Execution” (CTDE) framework. During the execution phase, each transporter is modeled as an individual DQN agent, selecting and executing actions based solely on its local observations and interacting independently with the environment. During the training phase, the experiences generated by all agents are aggregated into a shared replay buffer. Each agent then independently samples from this shared buffer to update its network parameters. This allows agents to learn from the collective experience of the system rather than from isolated individual trajectories, fostering a more cooperative policy without the burden of explicit communication. Furthermore, this design balances scalability with training stability and can, to some extent, mitigate the non-stationarity inherent in multi-agent learning.

- 4.

Centralized Paradigm: Soft Actor–Critic (SAC)

To explore the upper-performance bounds of a centralized control paradigm possessing complete global information and conducting top-level unified planning, we introduced the advanced Soft Actor–Critic (SAC) algorithm. As illustrated in

Figure 7, which shows the centralized SAC controller architecture, the controller observes the global state and outputs a joint action via its policy network. The value networks (Q-Networks) evaluate the action, and exploration is promoted by maximizing an entropy-based reward. As a unified central controller, SAC’s operational mechanism is fundamentally different from the DQN family. It employs an Actor–Critic architecture and optimizes based on a maximum entropy framework. This framework, by maximizing policy stochasticity concurrently with reward maximization, dramatically enhances the algorithm’s exploration capabilities and robustness, which is key to its powerful performance. In this study, the SAC controller receives the global state and directly outputs the joint action decision for all transporters, representing a “globally optimal” planning approach for solving such highly coordinated problems.

3.4.4. Reinforcement Learning Formulation

Our scheduling problem is formulated as a distributed multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL) framework where each of the N = 4 transporter agents learns an independent policy based on local observations. This decentralized design enables scalable real-time decision-making suitable for resource-constrained orchard environments.

Each agent

i observes an 8-dimensional state vector

comprising: (1) vehicle-specific features (position, load, time progress), (2) task distribution at representative nodes (queues at nodes 1 and 4, cumulative system demand), and (3) global coordination signals (cumulative system demand, load imbalance indicator). This design prioritizes information density while retaining essential coordination information. All features are normalized to [−1, 1] to facilitate neural network training. Complete mathematical specifications are provided in

Appendix C.1.

- 2.

Action Space

Each agent selects from a discrete action space where a0 represents waiting and ak (k > 0) represents navigating to task node k. For our configuration with M = 8 task points, the action space is limited to the 6 most frequently accessed nodes, yielding . All agents execute actions concurrently in a fully decentralized manner.

- 3.

Reward Function

The reward function encourages task completion while promoting operational efficiency:

where

rewards loading/unloading operations (+10 each),

incentivizes high load factors and penalizes empty travel, and

discourages idle time and invalid actions. Through sensitivity analysis, we determined optimal weights

α = 1.0,

β = 0.5,

γ = −1.0. The ratio

β/

α = 0.5 balances task completion priority with efficiency optimization. Detailed component definitions are provided in

Appendix C.2.

- 4.

Learning Objective

Each agent

i learns a policy

maximizing expected cumulative discounted reward

with discount factor

γ = 0.95. Agents are trained over

Tmax = 3000 time steps per episode using deep reinforcement learning algorithms (DQN, SAC, MARL-DQN; see

Section 3.4.3), typically converging within 1500–2000 episodes. While agents learn independently without explicit communication, coordination emerges implicitly through shared environment dynamics and global state signals.

3.4.5. Training Strategy and Hyperparameter Configuration

To ensure that all learning-based agents converge stably to their optimal performance within the complex scheduling environment, and to guarantee absolute fairness in the algorithmic comparison, we designed a standardized training pipeline. This pipeline incorporates both curriculum learning and systematic hyperparameter tuning.

Training an RL agent from scratch directly in the complex environment (e.g., 4 transporters and 8 task nodes) presents significant challenges, including the curse of dimensionality and sparse rewards, often making it difficult to learn an effective policy. To overcome this hurdle, we uniformly adopted a Curriculum Learning (CL) strategy for all learning-based algorithms (DQN, MARL-DQN, and SAC).

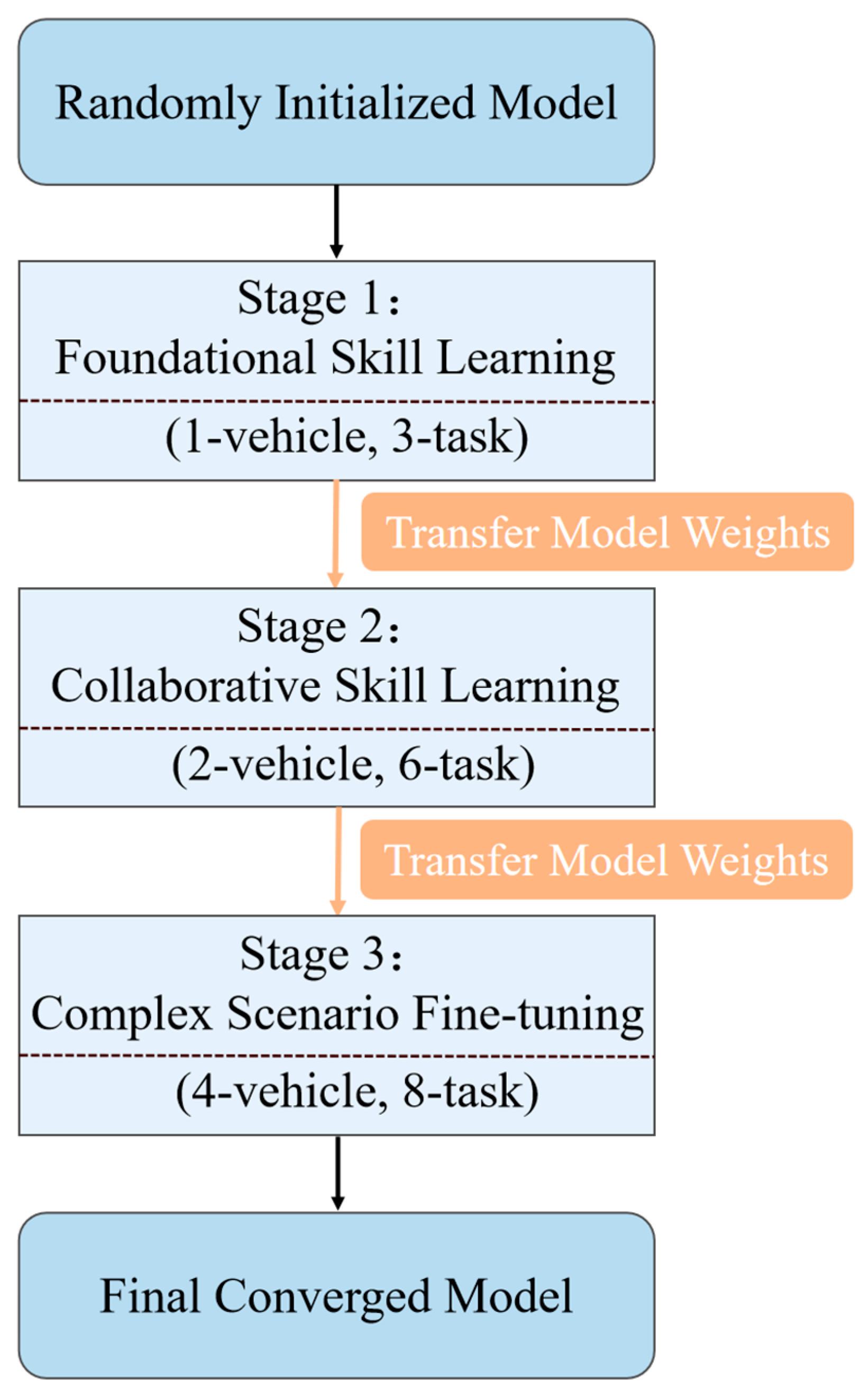

As illustrated in

Figure 8, the core idea of curriculum learning is to decompose the complex learning objective into a sequence of sub-tasks with increasing difficulty. The agent first masters fundamental skills in a simple environment, and then, the learned knowledge (i.e., model weights) is transferred to a more complex environment for fine-tuning. The specific curriculum is set as follows:

Phase 1: Basic Skills Learning (1-Transporter, 3-Task Nodes): The agent learns the fundamental logic of task selection and transport in the simplest setting.

Phase 2: Collaborative Skills Learning (2-Transporters, 6-Task Nodes): The agent inherits the knowledge from the previous phase and begins to learn collaborative strategies between two agents.

Phase 3: Complex Scenario Fine-Tuning (4-Transporters, 8-Task Nodes): The agent inherits the collaborative skills and performs final policy refinement in the complex environment that precisely matches our final testing scenario.

This “easy-to-hard” training paradigm significantly improves training stability and convergence speed, and it contributes to our ability to obtain high-performance policies in such a complex environment.

Figure 8.

The Curriculum Learning (CL) training pipeline, showing the three-stage process with model weight transfer.

Figure 8.

The Curriculum Learning (CL) training pipeline, showing the three-stage process with model weight transfer.

- 2.

Hyperparameter Configuration and Tuning

A fair algorithmic comparison is highly dependent on robust hyperparameter tuning. We employed a systematic methodology to determine the key hyperparameters.

Table 2 summarizes the final core hyperparameter configurations used for all learning-based algorithms in this study. These values were determined through a multi-stage process: first, we established initial parameter search ranges based on academic literature in related fields; second, we further narrowed the potential range of optimal parameters through preliminary exploratory experiments; finally, we conducted systematic hyperparameter tuning to identify robust parameter settings for our comparative evaluation. This process validated the robustness of our chosen parameters and supported fair comparisons across all algorithms.

State dimension represents the observation space for each individual agent. MARL-DQN employs distributed execution with 4 independent agents, each observing an 8-dimensional state vector. SAC uses centralized control over 4 agents, with each agent’s observation contributing to a global state representation. See

Appendix C.1 for detailed state space formulation. Action dimension of 6 comprises one waiting action plus five task node navigation actions, adaptively simplified from the full 8-node environment to maintain tractable learning complexity while retaining sufficient decision-making flexibility.

3.5. Emergency Task Response Strategies

Having established a comprehensive methodology for regular dynamic tasks, this study further investigates the system’s response capabilities when confronted with high-priority, emergent events. Emergency tasks, such as the urgent transport of agricultural equipment, differ fundamentally from routine goods transport in their objectives and constraints. They primarily emphasize response timeliness and the minimization of disruption to regular operations. Accordingly, we first established a distinct mathematical model and set of optimization objectives specifically for this emergency task scenario. Subsequently, building upon our established optimal platform, Framework 3, we designed and proposed two distinct emergency response strategies (Strategy 1 and Strategy 2). The objective of this comparison is to explore how different scheduling logics affect overall system efficiency while ensuring the high priority of emergency tasks is met.

The priority of emergency tasks is higher than that of regular goods in events of random task arrivals, and these tasks cannot be combined with other tasks for carpooling transport. The set of emergency tasks is represented as

, where t

u is the time when the

uth emergency task occurs.

and

are the loading and unloading points for this emergency task, respectively, and must not be the same task point.

is the total number of emergency tasks. As shown in

Figure 9, if the loading point number

is less than the unloading point number

, the task flow direction matches the direction of the transporter’s movement, as depicted by the green trajectory; the emergency task can be completed without passing through the initial position. Conversely, if the loading point number

is greater than the unloading point number

, since the transporter can only move in one direction and cannot reverse, as illustrated by the purple trajectory, it must travel via the initial position after loading to reach the unloading point.

Transporting ordinary goods primarily focuses on devising a scheduling plan that enables transporters to reach full capacity at the fewest possible task points. In contrast, transporting emergency tasks emphasises the timing of the task, the start and end positions, and the status of each transporter. The goal is to determine the transporter number to complete emergency tasks as quickly as possible while minimising the impact on the originally planned transport of ordinary goods. The objective function

for the dynamic scheduling model with randomly arriving emergency tasks is established as follows:

In the formula, represents the time when the system responds to the uth emergency task and assigns a transporter number. is the average difference between the system response time and the emergency task occurrence time, used to assess the response speed to emergency tasks. A smaller difference indicates a faster system response, with a zero difference signifying an immediate response. and represent the load rate and the number of rescheduling occurrences, respectively, when there are no emergency tasks and only ordinary goods arrive randomly. and represent the load rate and the number of rescheduling occurrences, respectively, under the same conditions of ordinary goods arriving randomly, but with emergency tasks present. is used to assess the impact of emergency tasks on the originally planned transport. Larger differences in indicate a greater negative impact on the transport of ordinary goods, with a zero difference indicating no impact.

The model assumptions and constraints are consistent with those under random task arrival events.

- 2.

Framework Design

The system primarily responds to random demands for ordinary goods before any emergency tasks arise. When an emergency task occurs, it is prioritised, and the transport of ordinary goods is either delayed or replanned. After the emergency task is completed, the system resumes responding to ordinary goods. Previously, in

Section 3.4.1 “Framework Design”, four scheduling frameworks were proposed and tested with different rescheduling methods aimed at improvement. Experiments showed that Framework 3 was the most effective (see detailed analysis in

Section 4.2). Based on Framework 3, two emergency task response strategies are proposed. The selection between these strategies depends on the operational tolerance for schedule adjustments. Strategy 1 (Initial-Position-Based Response) is applied when the system requires strict adherence to the pre-planned schedule. By restricting emergency dispatch to transporters at the initial position, it ensures zero additional rescheduling events for existing on-track tasks, making it suitable for scenarios where system stability is the absolute priority. In contrast, Strategy 2 (Proximity-Based Preemptive Response) is designated for scenarios where response timeliness is the primary objective. It employs a proximity-based logic to preempt the nearest eligible empty transporter; while this incurs a moderate increase in rescheduling events, our analysis demonstrates that this strategy achieves significantly faster response times without compromising the system’s core load efficiency.

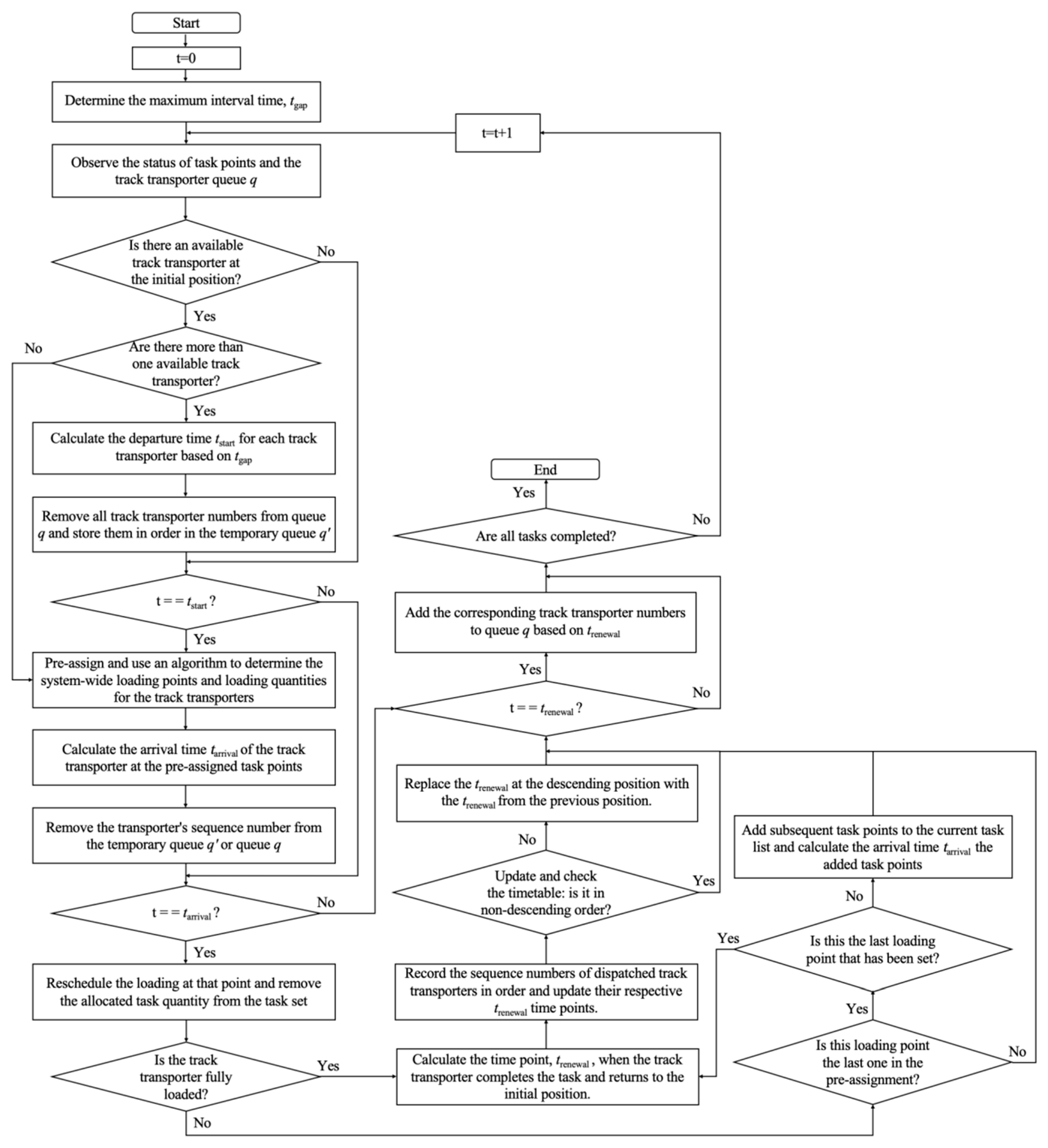

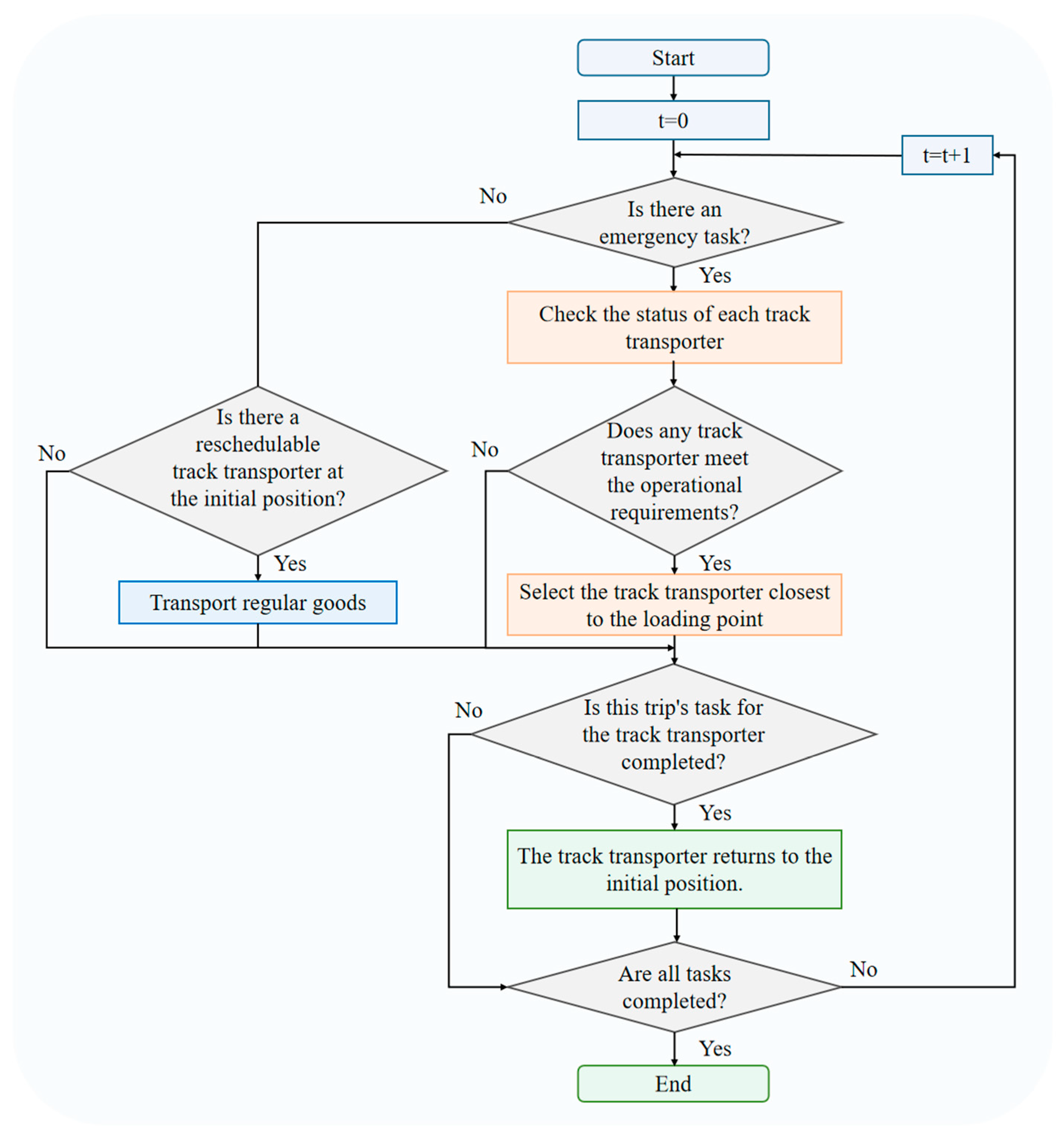

Strategy 1 responds to emergency tasks based on the periodic scheduling strategy of Framework 3. In Framework 3, the initial position is a key site for pre-allocating the system-wide loading points and quantities of regular goods. Adjustments to the actual loading quantities or additions of extra task points can be made at the target loading points. However, rescheduling at other locations is not permitted. Thus, Framework 3 ensures that transporters are assigned specific tasks before departing from the initial position. When an emergency task occurs, the first available transporter at the initial position can be used to prioritise the emergency task. After completing the emergency task, the transporter returns to the initial position to prepare for the next round of scheduling. If returning empty, the transporter may pass through the unloading point of the emergency task and subsequent task points to transport regular goods en route. The related algorithmic flowchart is detailed in

Figure 10.

The specific steps are summarised as follows:

- Step 1:

Initialise the Algorithm Parameters.

- Step 2:

Regularly Update Both Ordinary and Emergency Tasks.

- Step 3:

At the current time point t, if transporters are available at the initial position and no emergency tasks are present, transport ordinary goods and proceed to Step 5. If both emergency and ordinary tasks are present, the transporter prioritises the emergency task. If the loading point of the emergency task is less than the unloading point, calculate the arrival times to the emergency task’s loading and unloading points. Pre-allocate the unloading point and subsequent ordinary goods and then proceed to Step 5. If the loading point is greater than the unloading point, calculate the time to reach the emergency task’s loading point and the time for passing the initial position with emergency goods. If no transporters are available, proceed to Step 4.

- Step 4:

If the current time point t equals , the transporter passes the initial position. At this time, calculate the arrival time to the emergency task’s unloading point and pre-allocate the unloading point and subsequent ordinary goods. If t does not equal any , proceed to Step 5.

- Step 5:

If at the current time point t the transporter has completed its trip, it returns to the initial position ready for the next task. If the trip is not completed, proceed to Step 6.

- Step 6:

Determine if all tasks are completed. If not, continue the scheduling, increment the time point t by 1, and return to Step 2. If all tasks are completed, the scheduling ends and the complete scheduling plan is output.

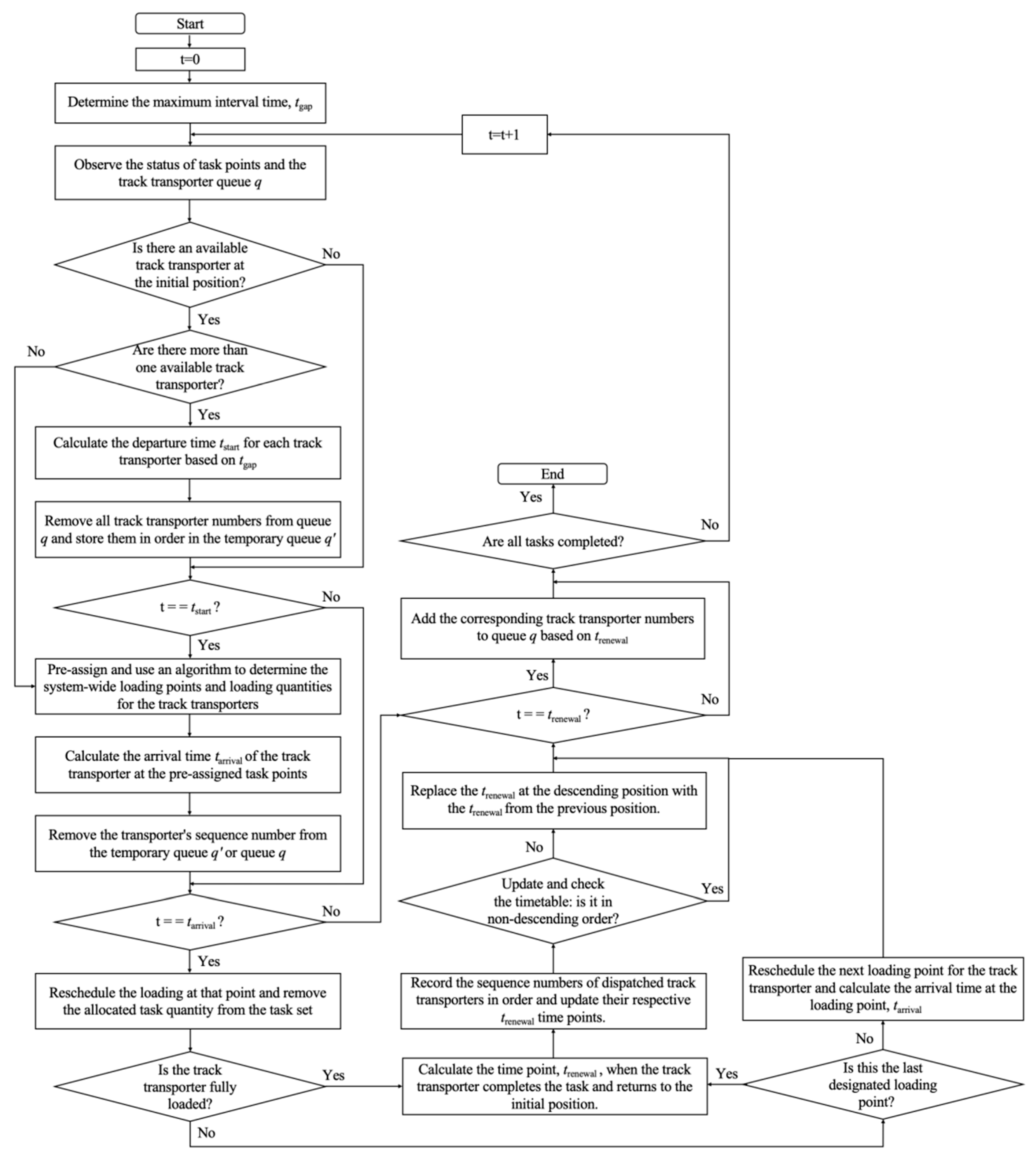

When an emergency task arises, transporters eligible to execute such tasks must meet the following criteria: they must be positioned before the target loading point and must not be carrying any regular goods. To respond to emergency tasks most rapidly, a proximity strategy will be employed, prioritising the nearest empty transporter to the target loading point.

- Situation 1:

As described in Strategy 1, if there is an available empty transporter at the initial position ready for rescheduling, it will be prioritised for the emergency task. After completing the emergency task, the transporter can continue to carry regular goods if it passes other task points.

- Situation 2:

If a transporter has been assigned a regular goods task but is still empty and appropriately located when the emergency task signal is received, its original regular goods task will be cancelled in favour of prioritising the emergency task. After completing the emergency task, the transporter will also execute subsequent regular goods tasks along the route.

- Situation 3:

For transporters assigned to emergency tasks, their position must meet specific transport requirements. If the assigned emergency task’s loading point is less than the unloading point, the transporter must be located before the emergency task’s loading point. If the loading point is greater than the unloading point, the transporter should have already passed the initial position and be located before the emergency task’s loading point. After completing the emergency task, the transporter continues to handle regular goods at subsequent task points.

If multiple transporters simultaneously meet these criteria, the one closest to the emergency task’s loading point will be chosen to execute the task. The related algorithmic flowchart is detailed in

Figure 11.