Regrowth and Yield Formation of ‘Qingtian No. 1’ Oat in Response to Cutting Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

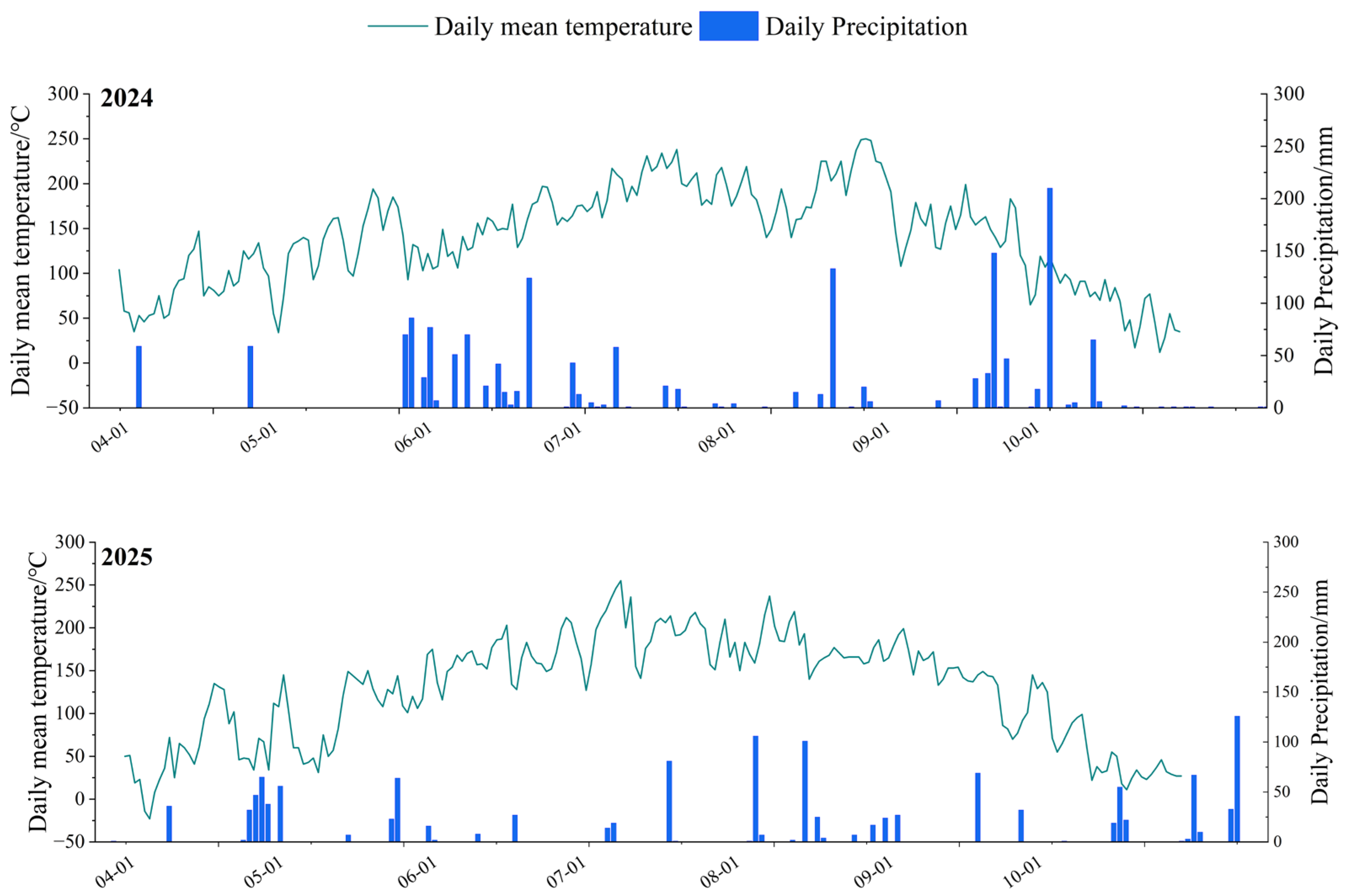

2.1. Experimental Site Overview

2.1.1. Site Location and Environmental Characteristics

2.1.2. Soil Characteristics

2.2. Experimental Design and Agronomic Management

2.2.1. Test Material and Experimental Design

2.2.2. Crop Establishment and Fertilization

2.2.3. Irrigation and Soil Moisture Monitoring

2.2.4. Harvest Schedule

2.3. Measurement Indicators and Methods

2.3.1. Photosynthetic Characteristics

2.3.2. Agronomic Traits and Yield

2.3.3. Forage Quality

2.3.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Total Productivity of the Oat ‘One-Sowing-Two-Harvest’ System

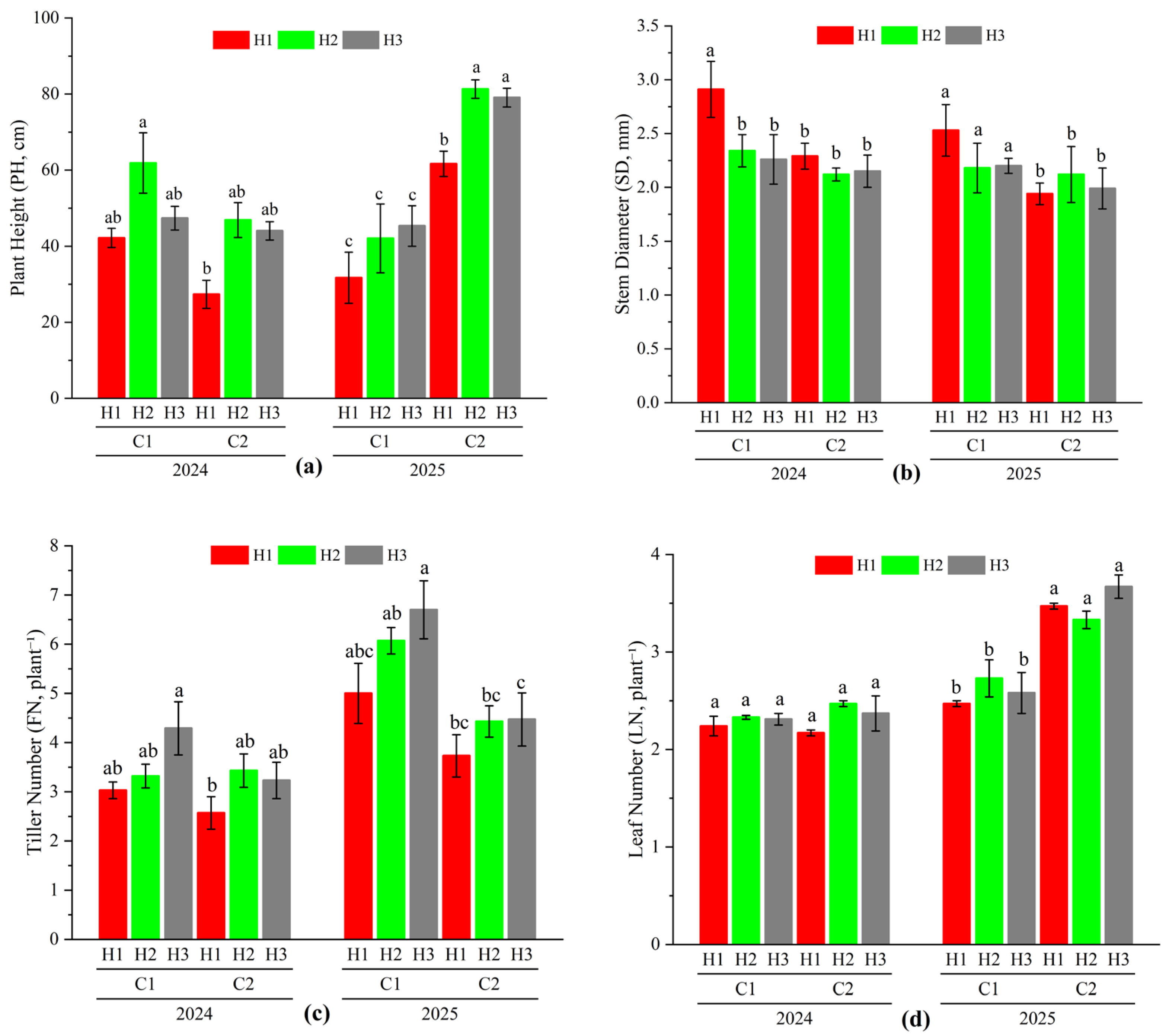

3.2. Effect of Different Cutting Treatments on Agronomic Traits of Oat During the Regrowth Stage

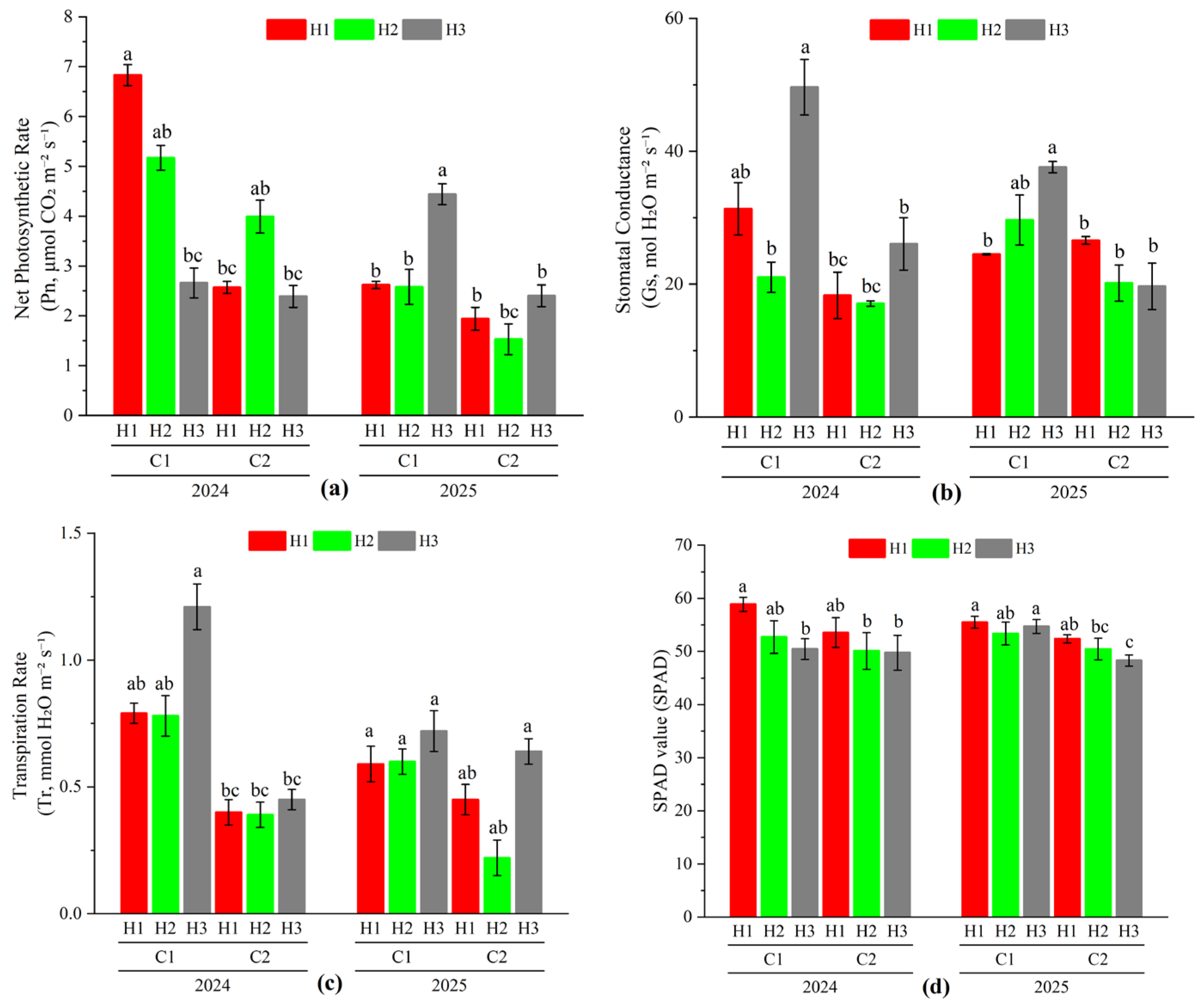

3.3. Effect of Different Cutting Treatments on Photosynthetic Characteristics of Oat During the Regrowth Stage

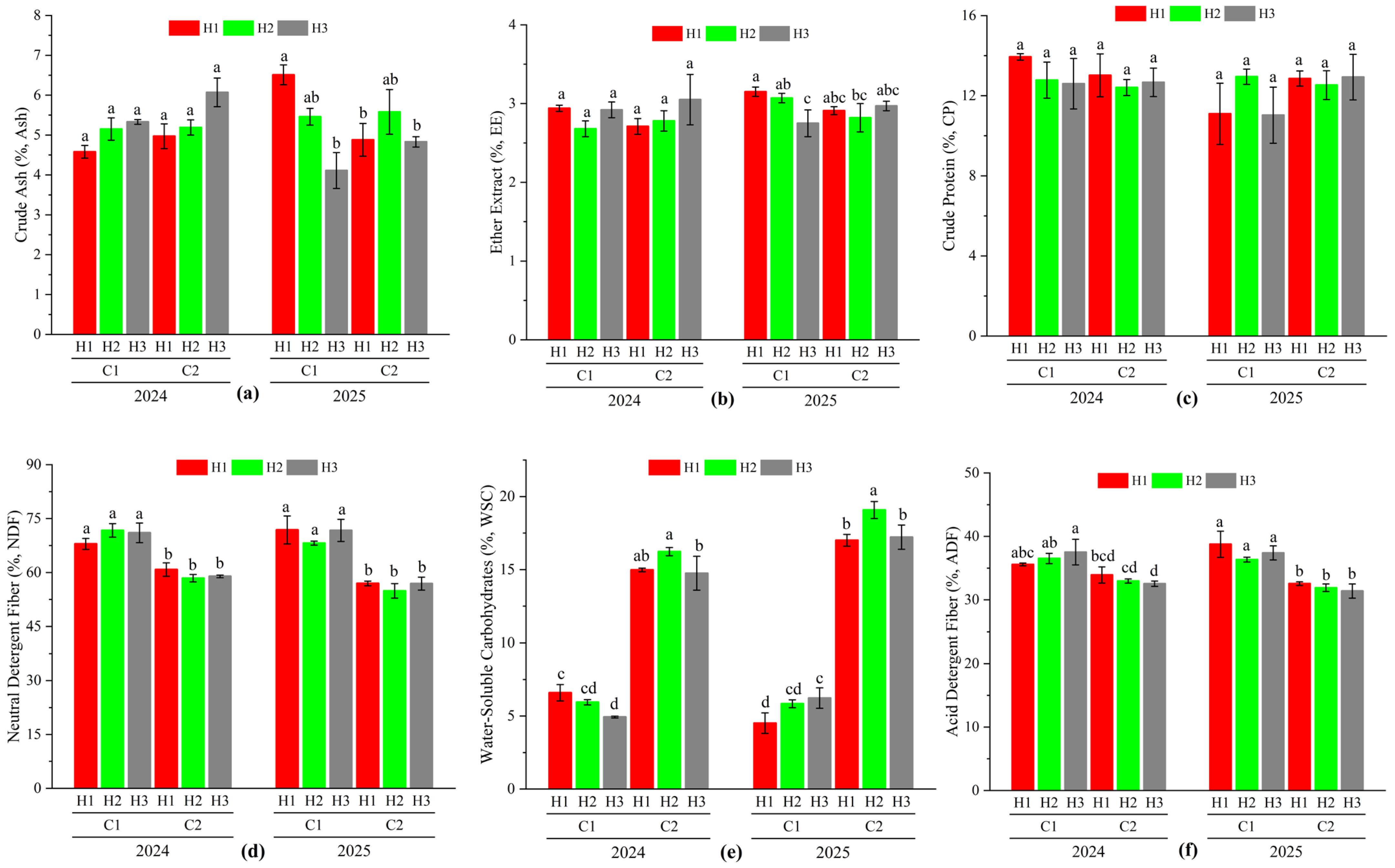

3.4. Effect of Different Cutting Treatments on Nutritional Quality of Oat During the Regrowth Stage

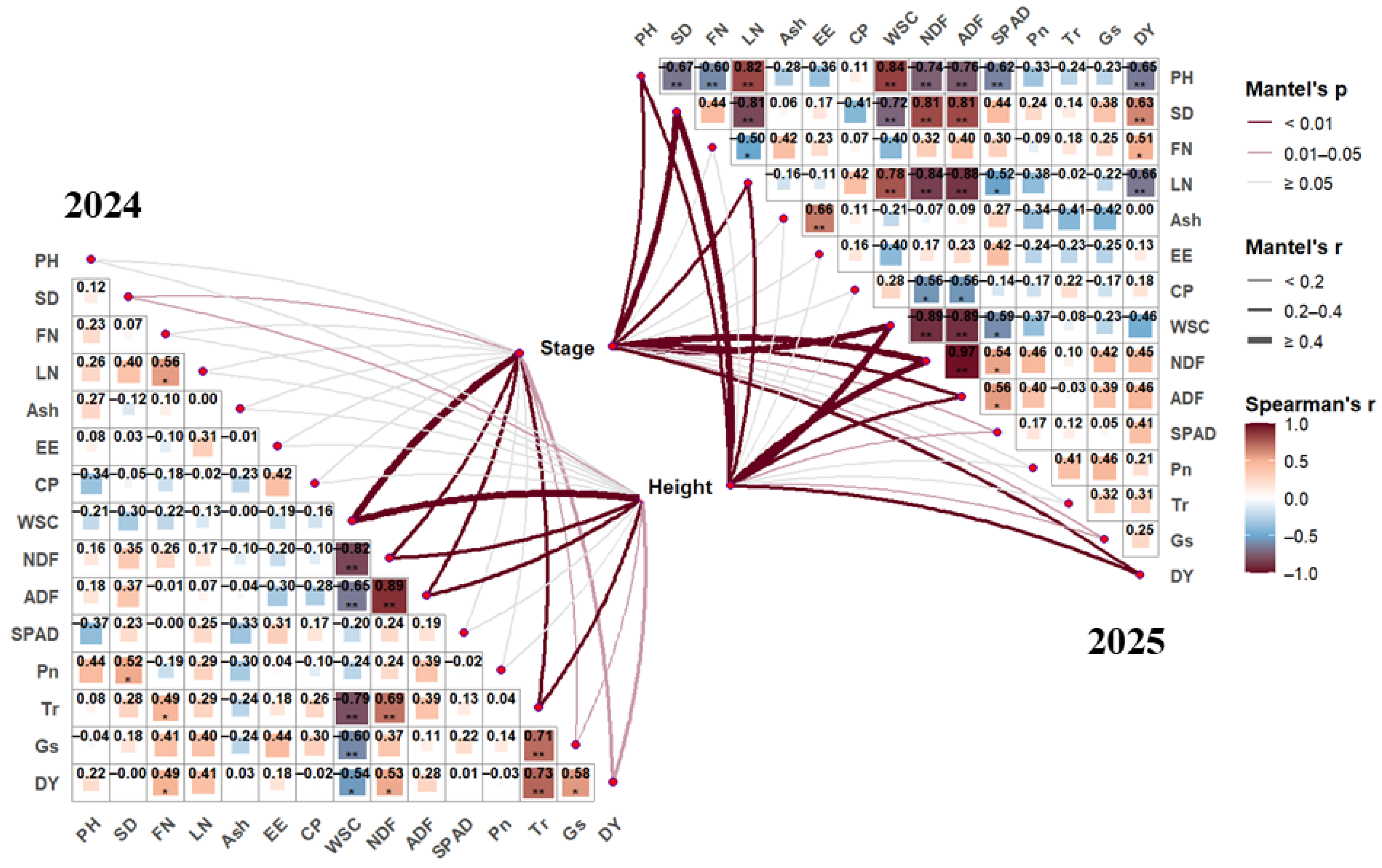

3.5. Correlation Analysis of Various Indicators in the Oat Regrowth Period

3.5.1. Correlation Analysis of Oat Regrowth Indicators in 2024

3.5.2. Correlation Analysis of Oat Regrowth Indicators in 2025

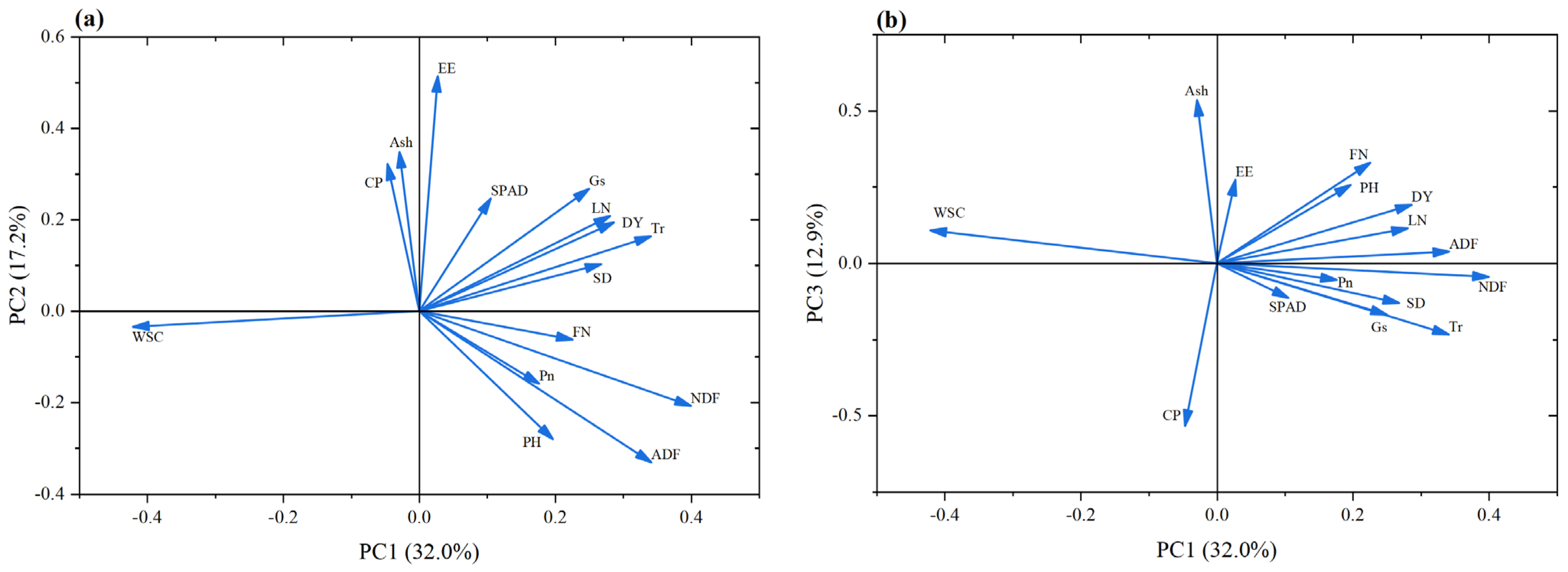

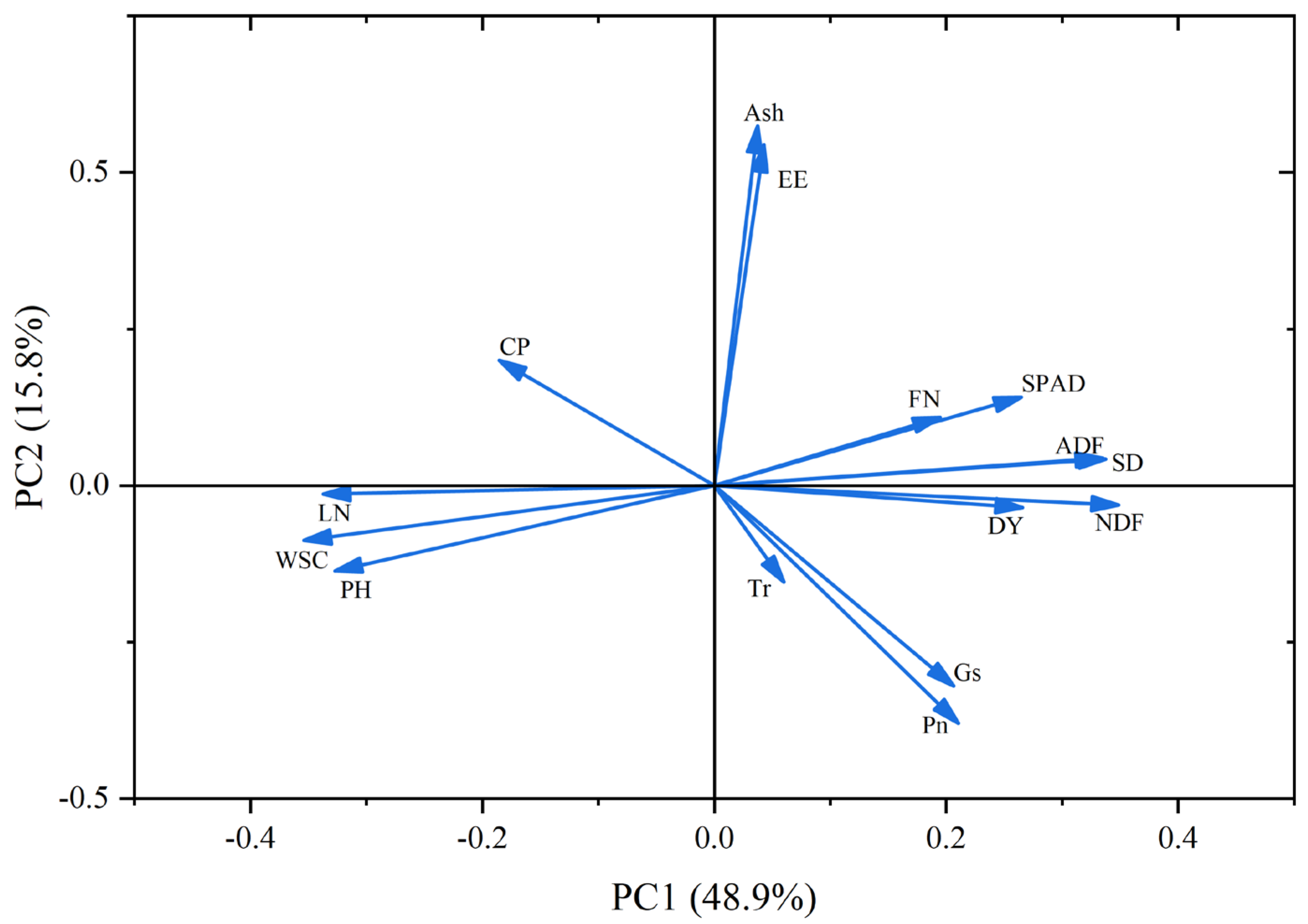

3.6. Principal Component Analysis and Comprehensive Evaluation of the Oat Regrowth Period

3.6.1. Principal Component Analysis and Comprehensive Evaluation of the Oat Regrowth Period in 2024

3.6.2. Principal Component Analysis and Comprehensive Evaluation of the Oat Regrowth Period in 2025

4. Discussion

4.1. Comprehensive Effects of Cutting Management on Production Performance and Agronomic Traits of Oat

4.2. Physiological Responses of Photosynthetic Characteristics and Nutritional Quality in Oat Under Cutting Management

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Pn | Net Photosynthetic Rate |

| Tr | Transpiration Rate |

| Gs | Stomatal Conductance |

| SPAD | Chlorophyll Content |

| PH | Plant Height |

| SD | Stem Diameter |

| LN | Number of Leaves |

| FN | Number of Tillers |

| FY | Fresh Forage Yield |

| DY | Dry Forage Yield |

| CP | Crude Protein |

| NDF | Neutral Detergent Fiber |

| ADF | Acid Detergent Fiber |

| Ash | Crude Ash |

| EE | Ether Extract |

| WSC | Water-Soluble Carbohydrates |

References

- Harris, R.B. Rangeland Degradation on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau: A Review of the Evidence of Its Magnitude and Causes. J. Arid Environ. 2010, 74, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ding, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Zeng, X.; Ge, X. Study on the Inversion and Spatiotemporal Variation Mechanism of Soil Salinization at Multiple Depths in Typical Oases in Arid Areas: A Case Study of Wei-Ku Oasis. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 315, 109542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Yeh, E.T.; Holden, N.M.; Yang, Y.; Du, G. The Effects of Enclosures and Land-Use Contracts on Rangeland Degradation on the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau. J. Arid Environ. 2013, 97, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Adamowski, J.F.; Deo, R.C.; Xu, X.; Gong, Y.; Feng, Q. Grassland Degradation on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau: Reevaluation of Causative Factors. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 2019, 72, 988–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Jia, G.; Wen, D.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, J.; Xu, Q.; Zhao, X.; Jiang, N.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y. Rumen Microbiota of Indigenous and Introduced Ruminants and Their Adaptation to the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1027138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.; You, Q.; Peng, F.; Dong, S.; Duan, H. Experimental Warming Aggravates Degradation-Induced Topsoil Drought in Alpine Meadows of the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau. Land Degrad. Dev. 2017, 28, 2343–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; De, S.; Belkheir, A. Avena Sativa (Oat), a Potential Neutraceutical and Therapeutic Agent: An Overview. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013, 53, 126–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daou, C.; Zhang, H. Oat Beta-Glucan: Its Role in Health Promotion and Prevention of Diseases. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2012, 11, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.Y.; Ma, B.B.; Lu, C.X. Spatio-Temporal Dynamics of Feed Grain Demand of Dairy Cows in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashilenje, D.S.; Amombo, E.; Hirich, A.; Kouisni, L.; Devkota, K.P.; Mouttaqi, A.E.; Nilahyane, A. Crop Species Mechanisms and Ecosystem Services for Sustainable Forage Cropping Systems in Salt-Affected Arid Regions. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 899926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabi, S.; ul Hussan, S.; Nabi, T.; Shikari, A.B.; Dar, Z.A.; Khuroo, N.S.; Lone, A.A.; Sofi, P.A.; Amin, R.; Wani, M.A. Bi-Environmental Evaluation of Oat (Avena sativa L.) Genotypes for Yield and Nutritional Traits under Cold Stress Conditions Using Multivariate Analysis. Plant Genet. Resour. 2024, 22, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Chen, S.-P.; Lin, G.-H. Compensatory Growth Responses to Clipping Defoliation in Leymus Chinensis (Poaceae) under Nutrient Addition and Water Deficiency Conditions. Plant Ecol. 2007, 196, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.A.; Muir, J.P.; Lambert, B.D. Overseeding Cool-Season Annual Legumes and Grasses into Dormant ‘Tifton 85’ Bermudagrass for Forage and Biomass. Crop Sci. 2018, 58, 964–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brummer, E.C.; Moore, K.J. Persistence of Perennial Cool-Season Grass and Legume Cultivars under Continuous Grazing by Beef Cattle. Agron. J. 2000, 92, 466–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zheng, H.; Wang, W.; Tang, Q. Cutting Time & Height Improve Carbon and Energy Use Efficiency of the Forage–Food Dual-Purpose Ratoon Rice Cropping. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borreani, G.; Odoardi, M.; Reyneri, A.; Tabacco, E. Effect of Cutting Height and Stage of Development on Lucerne Quality in the Po Plain. Ital. J. Agron. 2006, 1, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, H.; Tanaka, R.; Hakata, M. Grain Yield Response to Planting Date and Cutting Height of the First Crop in Rice Ratooning. Crop Sci. 2023, 63, 2539–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, D.R.; Culvenor, R.A. Improving the Grazing and Drought Tolerance of Temperate Perennial Grasses. N. Z. J. Agric. Res. 1994, 37, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkegaard, J.A.; Sprague, S.J.; Lilley, J.M.; McCormick, J.I.; Virgona, J.M.; Morrison, M.J. Physiological Response of Spring Canola (Brassica napus) to Defoliation in Diverse Environments. Field Crops Res. 2012, 125, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oral, H.H. Forage Yields and Nutritive Values of Oat and Triticale Pastures for Grazing Sheep in Early Spring. PeerJ 2024, 12, e17840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsunaga, A.; Sasaki, H. Effects of Plant Height and Cutting Height on Regrowth and Yield of Garland Chrysanthemum Ratooning. Hortic. J. 2023, 92, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Z.; Yi, X. Effects of Grazed Stubble Height and Timing of Grazing on Resprouting of Clipped Oak Seedlings. Agrofor. Syst. 2018, 93, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonemaru, J.; Kasuga, S.; Kawahigashi, H. QTL Analysis of Regrowth Ability in Bmr Sorghum (Sorghum Bicolor [L.] Moench) × Sudangrass (S. Bicolor Subsp. Drummondii) Populations. Grassl. Sci. 2022, 68, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volenec, J.J.; Ourry, A.; Joern, B.C. A Role for Nitrogen Reserves in Forage Regrowth and Stress Tolerance. Physiol. Plant. 1996, 97, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaghy; Fulkerson. Priority for Allocation of Water-Soluble Carbohydrate Reserves during Regrowth of Lolium perenne. Grass Forage Sci. 1998, 53, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J.H.; Caldwell, M.M. Soluble Carbohydrates, Concurrent Photosynthesis and Efficiency in Regrowth Following Defoliation: A Field Study with Agropyron Species. J. Appl. Ecol. 1985, 22, 907–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicensi, M.; Umburanas, R.C.; da Rocha Loures, F.S.; Koszalka, V.; Botelho, R.V.; de Ávila, F.W.; Müller, M.M.L. Residual Effect of Gypsum and Nitrogen Rates on Black Oat Regrowth and on Succeeding Soybean under No-Till. Int. J. Plant Prod. 2021, 15, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Miranda, A.; López-González, F.; Vieyra-Alberto, R.; Arriaga-Jordán, C.M. Grazed Barley for Dairy Cows in Small-Scale Systems in the Highlands of Mexico. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2022, 21, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, A.; Qiu, Y.; Raihan, T.; Paudel, B.; Dahal, S.; Zhuang, Y.; Galla, A.; Auger, D.; Yen, Y. The Genetics and Genome-Wide Screening of Regrowth Loci, a Key Component of Perennialism in Zea Diploperennis. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2019, 9, 1393–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Wang, S.; Ye, W.; Yao, Y.; Sun, F.; Zhang, C.; Liu, S.; Xi, Y. Effect of Mowing on Wheat Growth at Seeding Stage. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannerkorpi, P.; Brandt, M. Feeding Value of Whole-Crop Wheat Silage for Ruminants Related to Stage of Maturity and Cutting Height. Arch. Für Tierernaehrung 1993, 45, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Lai, X.; Shen, Y. Response of Dual-Purpose Winter Wheat Yield and Its Components to Sowing Date and Cutting Timing in a Semiarid Region of China. Crop Sci. 2021, 62, 425–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perazzo, A.F.; Carvalho, G.G.P.; Santos, E.M.; Bezerra, H.F.C.; Silva, T.C.; Pereira, G.A.; Ramos, R.C.S.; Rodrigues, J.A.S. Agronomic Evaluation of Sorghum Hybrids for Silage Production Cultivated in Semiarid Conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.B.; Alpuerto, J.B.; Tracy, B.F.; Fukao, T. Physiological Effect of Cutting Height and High Temperature on Regrowth Vigor in Orchardgrass. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bremner, J.M. Determination of Nitrogen in Soil by the Kjeldahl Method. J. Agric. Sci. 1960, 55, 11–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soest, P.J.V.; Robertson, J.B.; Lewis, B.A. Methods for Dietary Fiber, Neutral Detergent Fiber, and Nonstarch Polysaccharides in Relation to Animal Nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 1991, 74, 3583–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B. Determination of Related Substances in Estradiol Valerate Tablet by Use of HPLC Method. Curr. Pharm. Anal. 2018, 14, 513–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiex, N.J.; Anderson, S.; Gildemeister, B.; Adcock, W.; Boedigheimer, J.; Bogren, E.; Coffin, R.; Conway, K.; DeBaker, A.; Frankenius, E.; et al. Crude Fat, Diethyl Ether Extraction, in Feed, Cereal Grain, and Forage (Randall/Soxtec/Submersion Method): Collaborative Study. J. AOAC Int. 2003, 86, 888–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiex, N.; Novotny, L.; Crawford, A. Determination of Ash in Animal Feed: AOAC Official Method 942.05 Revisited. J. AOAC Int. 2012, 95, 1392–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, S.; Detling, J.K. The Effects of Defoliation and Competition on Regrowth of Tillers of Two North American Mixed-Grass Prairie Graminoids. Oikos 1984, 43, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culvenor, R. Effect of Cutting During Reproductive Development on the Regrowth and Regenerative Capacity of the Perennial Grass, Phalaris aquatica L., in a Controlled Environment. Ann. Bot. 1993, 72, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, W.G.; Caldwell, M.M. The Effects of the Spatial Pattern of Defoliation on Regrowth of a Tussock Grass: I. Growth Responses. Oecologia 1989, 80, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, D.; Doce, R.R.; Juskiw, P.; Zhou, G.; Baron, V.S. Diverse Grain-Filling Dynamics Affect Harvest Management of Forage Barley and Triticale Cultivars. Agron. J. 2018, 110, 1017–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirmon, P. The Effect of Harvest Cutting Height and Hybrid Maturity Class on Forage Nutritive Values and Ratoon Regrowth Potential of Sorghum Sudangrass in the Texas High Plains. Doctoral Dissertation, West Texas A&M University, Canyon, TX, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Rezaei, E.E.; Webber, H.; Asseng, S.; Boote, K.; Durand, J.L.; Ewert, F.; Martre, P.; MacCarthy, D.S. Climate Change Impacts on Crop Yields. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 831–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, R.; Vanga, S.K.; Wang, J.; Orsat, V.; Raghavan, V. Millets for Food Security in the Context of Climate Change: A Review. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Mo, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Tang, Q.; Xu, J.; Pan, S.; Wang, Y.; Chen, G.; Hu, Y. Appropriate Stubble Height Can Effectively Improve the Rice Quality of Ratoon Rice. Foods 2024, 13, 1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merino, V.M.; Aguilar, R.; Piña, L.F.; Garriga, M.; Ostria-Gallardo, E.; López, M.D.; Noriega, F.; Campos, J.; Navarrete, S.; Rivero, M.J. Regrowth Dynamics and Morpho-Physiological Characteristics of Plantago Lanceolata under Different Defoliation Frequencies and Intensities. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0310009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roche, J.; Turnbull, M.H.; Guo, Q.; Novák, O.; Späth, J.; Gieseg, S.P.; Jameson, P.E.; Love, J. Coordinated Nitrogen and Carbon Remobilization for Nitrate Assimilation in Leaf, Sheath and Root and Associated Cytokinin Signals during Early Regrowth of Lolium perenne. Ann. Bot. 2017, 119, 1353–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, R.S.; Caldwell, M.M. A Test of Compensatory Photosynthesis in the Field: Implications for Herbivory Tolerance. Oecologia 1984, 61, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, N.; Masood, A.; Khan, N.A. Analyzing the Significance of Defoliation in Growth, Photosynthetic Compensation and Source-Sink Relations. Photosynthetica 2012, 50, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Ji, T.; Liu, X.; Li, Q.; Sairebieli, K.; Wu, P.; Song, H.; Wang, H.; Du, N.; Zheng, P.; et al. Defoliation Significantly Suppressed Plant Growth Under Low Light Conditions in Two Leguminosae Species. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 777328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Favre, J.; López, I.F.; Cranston, L.M.; Donaghy, D.J.; Kemp, P.D.; Ordóñez, I.P. Functional Contribution of Two Perennial Grasses to Enhance Pasture Production and Drought Resistance under a Leaf Regrowth Stage Defoliation Criterion. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2022, 209, 144–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Américo, L.F.; Duchini, P.G.; Schmitt, D.; Guzatti, G.C.; Lattanzi, F.A.; Sbrissia, A.F. Nitrogen Nutritional Status in Perennial Grasses under Defoliation: Do Stubble Height and Mixed Cultivation Matter? J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2021, 184, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Zhao, M.; Li, Q.; Liu, X.; Song, H.; Peng, X.; Wang, H.; Yang, N.; Fan, P.; Wang, R.; et al. Effects of Defoliation Modalities on Plant Growth, Leaf Traits, and Carbohydrate Allocation in Amorpha fruticosa L. and Robinia pseudoacacia L. Seedlings. Ann. For. Sci. 2020, 77, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmstead, A.L.; Rhode, P.W. Adapting North American Wheat Production to Climatic Challenges, 1839–2009. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 108, 480–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meuriot, F.; Prud‘Homme, M.-P.; Noiraud-Romy, N. Defoliation, wounding, and methyl jasmonate induce expression of the sucrose lateral transporter LpSUT1 in ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.). Physiol. Plant. 2022, 174, e13744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissinen, O.; Kalliainen, P.; Jauhiainen, L. Development of Yield and Nutritive Value of Timothy in Primary Growth and Regrowth in Northern Growing Conditions. Agric. Food Sci. 2010, 19, 252–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monção, F.P.; Costa, M.A.M.S.; Rigueira, J.P.S.; Sales, E.C.J.d.; Leal, D.B.; Silva, M.F.P.d.; Gomes, V.M.; Chamone, J.M.A.; Alves, D.D.; Carvalho, C.d.C.S.; et al. Productivity and Nutritional Value of BRS Capiaçu Grass (Pennisetum Purpureum) Managed at Four Regrowth Ages in a Semiarid Region. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2019, 52, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Texture Class (USDA) | Clay (<0.002 mm) % | Silt (0.002–0.05 mm) % | Sand (0.05–2 mm) % | Bulk Density/ (g cm−3) | Field Capacity (−33 kPa)/ (cm3 cm−3) | Permanent Wilting Point (−1500 kPa)/ (cm3 cm−3) | Saturated Hydraulic Conductivity/ (cm day−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sandy Loam | 15.2 | 28.7 | 56.1 | 1.52 | 0.25 | 0.10 | 25 |

| Electrical Conductivity/ (dS m−1) | Organic Matter/ (g·kg−1) | Total Nitrogen/ (g·kg−1) | Total Phosphorus/ (g·kg−1) | Total Potassium/ (g·kg−1) | Ammonium Nitrogen/ (mg·kg−1) | Nitrate Nitrogen/ (mg·kg−1) | Available Phosphorus/ (mg·kg−1) | Available Potassium/ (mg·kg−1) | Soil Salinity/ (g·kg−1) | Soil pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.40 | 18.13 | 0.83 | 0.44 | 21.72 | 6.39 | 21.87 | 28.08 | 129.61 | 2.40 | 8.46 |

| Year | Cutting Stage | Stubble Height | First Harvest DMY (t/ha) | Regrowth DMY (t/ha) | Total Seasonal DMY (t/ha) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 | C1 | H1 | 0.77 ± 0.08bc | 0.31 ± 0.07bc | 1.08 ± 0.04ab |

| H2 | 0.68 ± 0.02c | 0.44 ± 0.04a | 1.12 ± 0.06ab | ||

| H3 | 0.62 ± 0.05c | 0.40 ± 0.05ab | 1.02 ± 0.10b | ||

| C2 | H1 | 1.13 ± 0.13a | 0.18 ± 0.03d | 1.31 ± 0.14a | |

| H2 | 0.96 ± 0.10ab | 0.24 ± 0.02cd | 1.21 ± 0.09ab | ||

| H3 | 0.82 ± 0.12bc | 0.34 ± 0.07abc | 1.16 ± 0.08ab | ||

| 2025 | C1 | H1 | 0.65 ± 0.06b | 0.40 ± 0.15ab | 1.05 ± 0.19a |

| H2 | 0.53 ± 0.01b | 0.57 ± 0.03a | 1.09 ± 0.04a | ||

| H3 | 0.60 ± 0.04b | 0.53 ± 0.10a | 1.13 ± 0.13a | ||

| C2 | H1 | 1.05 ± 0.04a | 0.15 ± 0.04c | 1.20 ± 0.02a | |

| H2 | 1.03 ± 0.05a | 0.22 ± 0.04bc | 1.25 ± 0.09a | ||

| H3 | 0.91 ± 0.11a | 0.13 ± 0.04c | 1.05 ± 0.07a | ||

| F | Year (Y) | 0.875 | 0.279 | 0.092 | |

| Cutting Stage (C) | 2.698 | 125.914 ** | 391.567 ** | ||

| Stubble Height (H) | 4.454 * | 5.646 | 0.811 | ||

| Y × C | 6.471 * | 17.056 ** | 0.294 | ||

| Y × H | 0.366 | 0.265 | 0.241 | ||

| C × H | 0.760 | 3.287 | 0.692 | ||

| Y × C × H | 1.120 | 0.089 | 0.536 | ||

| Source of Variation | Plant Height (PH) | Stem Diameter (SD) | Tiller Number (FN) | Leaf Number (LN) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year (Y) | 11.464 ** | 12.314 ** | 24.65 ** | 139.912 ** |

| Cutting Stage (C) | 59.933 ** | 238.506 ** | 34.043 ** | 35.611 ** |

| Stubble Height (H) | 5.623 ** | 1.285 | 0.876 | 10.003 ** |

| Y × C | 41.659 ** | 28.013 ** | 3.089 | 59.414 ** |

| Y × H | 0.570 | 1.026 | 0.180 | 3.816 |

| C × H | 1.068 | 1.744 | 1.079 | 0.073 |

| Source of Variation | Net Photosynthetic Rate (Pn) | Stomatal Conductance (Gs) | Transpiration Rate (Tr) | SPAD Value (SPAD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year (Y) | 5.669 * | 0.077 | 1.854 | 0.011 |

| Cutting Stage (C) | 19.966 ** | 30.735 ** | 21.342 ** | 708.708 ** |

| Stubble Height (H) | 0.025 | 2.109 | 1.679 | 2.759 |

| Y × C | 0.335 | 0.646 | 3.445 | 0.311 |

| Y × H | 3.935 ** | 1.951 | 0.090 | 0.935 |

| C × H | 0.827 | 2.228 | 0.286 | 0.945 |

| Source of Variation | Crude Ash (Ash) | Ether Extract (EE) | Crude Protein (CP) | Water-Soluble Carbohydrates (WSC) | Acid Detergent Fiber (ADF) | Neutral Detergent Fiber (NDF) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year (Y) | 0.375 | 1.909 | 1.889 | 12.955 ** | 0.045 | 1.749 |

| Cutting Stage (C) | 37.998 ** | 540.007 ** | 234.206 ** | 1075.48 ** | 1331.492 ** | 1313.695 ** |

| Stubble Height (H) | 0.003 | 0.354 | 0.199 | 3.656 * | 0.664 | 0.659 |

| Y × C | 1.598 | 0.394 | 2.326 | 21.006 ** | 3.179 | 2.672 |

| Y × H | 3.451 * | 0.108 | 0.401 | 3.627 * | 0.835 | 1.051 |

| C × H | 1.311 | 1.777 | 0.456 | 1.648 | 0.425 | 0.293 |

| Cutting Stage | Stubble Height | F | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | H1 | 0.230 | 3 |

| H2 | 0.520 | 1 | |

| H3 | 0.234 | 2 | |

| C2 | H1 | −0.605 | 6 |

| H2 | −0.173 | 4 | |

| H3 | −0.206 | 5 |

| Cutting Stage | Stubble Height | F | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | H1 | 0.420 | 3 |

| H2 | 0.594 | 2 | |

| H3 | 0.652 | 1 | |

| C2 | H1 | −0.483 | 4 |

| H2 | −0.600 | 6 | |

| H3 | −0.584 | 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jia, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, C.; Pu, X.; Zhang, H.; Xue, F.; Sun, H. Regrowth and Yield Formation of ‘Qingtian No. 1’ Oat in Response to Cutting Management. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2542. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242542

Jia Y, Zhao Y, Xu C, Pu X, Zhang H, Xue F, Sun H. Regrowth and Yield Formation of ‘Qingtian No. 1’ Oat in Response to Cutting Management. Agriculture. 2025; 15(24):2542. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242542

Chicago/Turabian StyleJia, Yangji, Yuanyuan Zhao, Chengti Xu, Xiaojian Pu, Haiying Zhang, Fengjuan Xue, and Hao Sun. 2025. "Regrowth and Yield Formation of ‘Qingtian No. 1’ Oat in Response to Cutting Management" Agriculture 15, no. 24: 2542. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242542

APA StyleJia, Y., Zhao, Y., Xu, C., Pu, X., Zhang, H., Xue, F., & Sun, H. (2025). Regrowth and Yield Formation of ‘Qingtian No. 1’ Oat in Response to Cutting Management. Agriculture, 15(24), 2542. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242542