Space Agriculture: A Comprehensive Systems-Level Review of Challenges and Opportunities

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Critically examine the key challenges and barriers to sustainable space agriculture across environmental, resource, biological, and operational dimensions.

- Highlight the interconnections among these factors and their implications for integrated system design.

- Synthesize current strategies and innovations, including controlled environment agriculture, regolith remediation, hydroponics, genetic engineering, robotics, and Artificial Intelligence (AI), and assess their potential for extraterrestrial application.

- Draw parallels with terrestrial challenges, emphasizing how lessons from space agriculture can inform food security, climate adaptation, and degraded-land restoration on Earth.

- Identify persistent uncertainties and future directions, providing a structured foundation to guide cross-disciplinary innovation in support of long-duration human missions.

Scope and Literature Collection

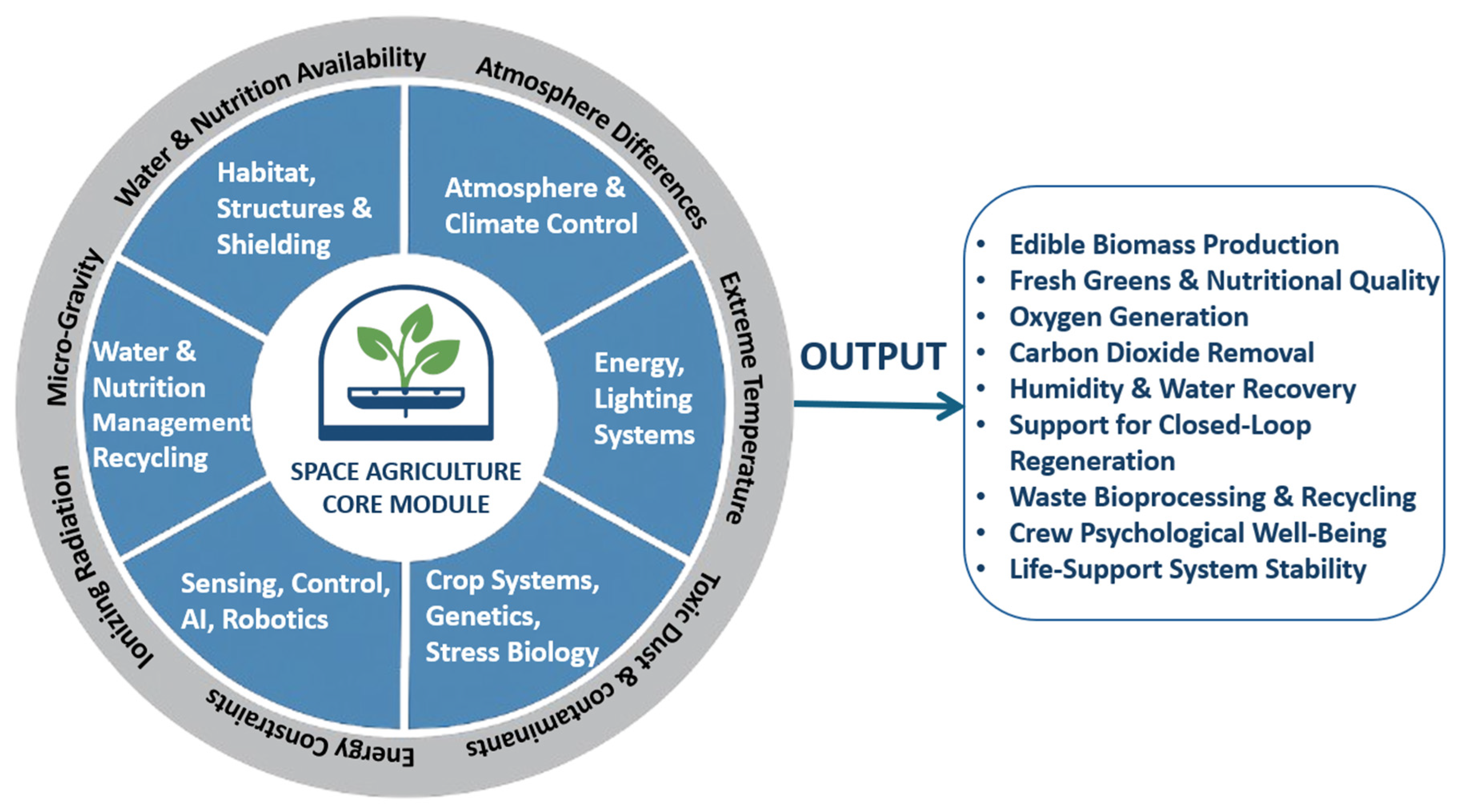

2. Challenges in Space Agriculture

2.1. Biological and Agricultural Challenges

2.1.1. Crop Selection

| Crop Type | Example Crop (Cultivar) | Test Environment | Outcome/Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leafy greens | Lettuce (‘Outredgeous’, ‘Waldmann’s Green’) | ISS * Veggie | Safe crew consumption |

| Mustards (Mizuna, ‘Wasabi’, ‘Amara’) | ISS * Veggie | Reliable growth; added menu diversity | |

| Pak choi (‘Extra Dwarf’) | ISS * Veggie | Efficient biomass per volume | |

| Kale (‘Red Russian’) | ISS * Veggie | Nutrient-dense | |

| Chinese cabbage (‘Tokyo Bekana’) | ISS * Veggie | Failed due to elevated CO2 | |

| Lettuce (‘Dragoon’) | ISS * Veggie | Failed due to watering and seed storage issues; needs retest | |

| Lettuce (‘Paris Island’) | Commercial candidate | ||

| Root crops | Radish (‘Cherry Belle’) | ISS * APH | Crisp texture, psychological appeal |

| Cereal crop | Wheat (‘Apogee’ dwarf) | ISS * APH | Not consumed |

| Fruiting crops | Pepper (‘Española Improved’) | ISS * APH | First fruiting crop validated; strong crew acceptance |

| Tomato (‘Red Robin’) | ISS * Veggie | Unsuccessful (watering issues); retest needed | |

| Tomato (‘Mohamed’) | Candidate ready for CRL6 * test | ||

| Small fruit | Strawberry (‘Delizz’) | Grows well from seed | |

| Legumes | Pea (‘Feisty’, ‘Yellow Snap’) | Candidate crop; ready for CRL4 * test |

2.1.2. Plant Health and Disease Management

2.1.3. Genetic Stability and Reproductive Viability

2.2. Resource Availability and Sustainability Challenges

2.2.1. Water Availability and Recycling

2.2.2. Soil and Regolith Utilization

2.2.3. Nutrient Limitations

2.3. Environmental Challenges

2.3.1. Solar Energy and Radiation

2.3.2. Atmosphere Differences

2.3.3. Plant Physiology (Temperature, Humidity, Gravity), and Cultivation Systems

2.4. Operational Challenges

2.4.1. Space Constraints and Efficiency

2.4.2. Energy Constraints and Power Management

2.4.3. Crew Interaction and Human Factors

2.4.4. Psychological and Ethical Challenges

2.5. System Reliability and Risk Management

2.5.1. Backup Systems and Redundancy

2.5.2. Unknown Unknowns

3. Engineering and Technological Solutions

3.1. Controlled Environment Agriculture (CEA)

3.2. Water Management and Recycling

3.3. Gravity Mitigation Strategies

3.4. Radiation Shielding and Atmospheric Solutions

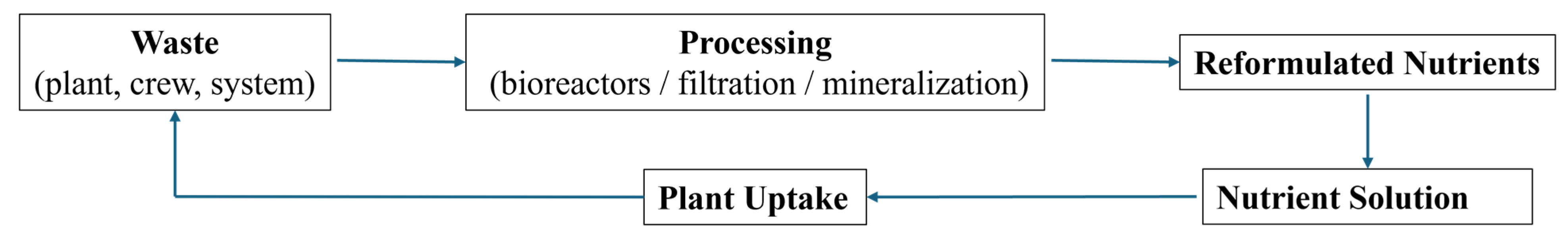

3.5. Nutrient Availability and Recycling

3.6. Advanced Sensor Systems

3.7. Automation and Robotics

3.8. Artificial Intelligence and Data Management

3.9. Biotechnological and Genetic Approaches

3.10. In Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU)

3.11. Redundancy and Backup Systems

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cohen, B. Artemis program overview. In Proceedings of the Endurance Science Workshop, Pasadena, CA, USA, 9–11 August 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Verseux, C.; Poulet, L.; de Vera, J.-P. Bioregenerative life-support systems for crewed missions to the Moon and Mars. Front. Astron. Space Sci. 2022, 9, 977364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, R.J.; Porter, W.; Goli, K.; Rosenthal, R.; Butler, N.; Jones, J.A. Biologically-based and physiochemical life support and in situ resource utilization for exploration of the solar system—Reviewing the current state and defining future development needs. Life 2021, 11, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeler, R.M. Agriculture for Space: People and Places Paving the Way. Open Agric. 2017, 2, 14–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, R.M. Plants for human life support in space: From Myers to Mars. Gravitational Space Biol. 2010, 23, 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- De Pascale, S.; Arena, C.; Aronne, G.; De Micco, V.; Pannico, A.; Paradiso, R.; Rouphael, Y. Biology and crop production in Space environments: Challenges and opportunities. Life Sci. Space Res. 2021, 29, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neukart, F. Towards Sustainable Horizons: A Comprehensive Blueprint for Mars Colonization. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dundas, C.M.; Bramson, A.M.; Ojha, L.; Wray, J.J.; Mellon, M.T.; Byrne, S.; McEwen, A.S.; Putzig, N.E.; Viola, D.; Sutton, S.; et al. Exposed subsurface ice sheets in the Martian mid-latitudes. Science 2018, 359, 199–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasiviswanathan, P.; Swanner, E.D.; Halverson, L.J.; Vijayapalani, P. Farming on Mars: Treatment of basaltic regolith soil and briny water simulants sustains plant growth. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0272209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davila, A.F.; Willson, D.; Coates, J.D.; McKay, C.P. Perchlorate on Mars: A chemical hazard and a resource for humans. Int. J. Astrobiol. 2013, 12, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamelink, G.W.W.; Frissel, J.Y.; Krijnen, W.H.J.; Verwoert, M.R.; Goedhart, P.W. Can plants grow on Mars and the moon: A growth experiment on Mars and moon soil simulants. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e103138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J.S.; Wheeler, R.M.; Pamphile, R. Host-microbe interactions in microgravity: Assessment and implications. Life 2014, 4, 250–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medina, F.J.; Manzano, A.; Villacampa, A.; Ciska, M.; Herranz, R. Understanding Reduced Gravity Effects on Early Plant Development Before Attempting Life-Support Farming in the Moon and Mars. Front. Astron. Space Sci. 2021, 8, 729154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadiji, A.E.; Yadav, A.N.; Santoyo, G.; Babalola, O.O. Understanding the plant-microbe interactions in environments exposed to abiotic stresses: An overview. Microbiol. Res. 2023, 271, 127368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monje, O.; Stutte, G.W.; Goins, G.D.; Porterfield, D.M.; Bingham, G.E. Farming in space: Environmental and biophysical concerns. Adv. Space Res. 2003, 31, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulet, L.; Zeidler, C.; Bunchek, J.; Zabel, P.; Vrakking, V.; Schubert, D.; Massa, G.; Wheeler, R. Crew time in a space greenhouse using data from analog missions and Veggie. Life Sci. Space Res. 2021, 31, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, M.; Pechurkin, N.S.; Allen, J.P.; Somova, L.A.; Gitelson, J.I. Closed ecological systems, space life support and biospherics. In Environmental Biotechnology; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 517–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, H.; Zhou, W.; Zheng, Z.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, M.; Jiang, Z.; Zheng, H.; Yuan, L.; Yang, J.; et al. Exploring plant responses to altered gravity for advancing space agriculture. Plant Commun. 2025, 6, 101370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffei, M.E.; Balestrini, R.; Costantino, P.; Lanfranco, L.; Morgante, M.; Battistelli, A.; Del Bianco, M. The physiology of plants in the context of space exploration. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frossard, E.; Crain, G.; de Azcárate Bordóns, I.G.; Hirschvogel, C.; Oberson, A.; Paille, C.; Pellegri, G.; Udert, K.M. Recycling nutrients from organic waste for growing higher plants in the Micro Ecological Life Support System Alternative (MELiSSA) loop during long-term space missions. Life Sci. Space Res. 2024, 40, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, H. Going beyond reliability to robustness and resilience in space life support systems. In Proceedings of the 50th International Conference on Environmental Systems, Virtual, 12–15 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Owens, A.C. Quantitative Probabilistic Modeling of Environmental Control and Life Support System Resilience for Long-Duration Human Spaceflight. Master’s Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Volk, T. Considerations in miniaturizing simplified agro-ecosystems for advanced life support. Ecol. Eng. 1996, 6, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Micco, V.; Aronne, G.; Caplin, N.; Carnero-Diaz, E.; Herranz, R.; Horemans, N.; Legué, V.; Medina, F.J.; Pereda-Loth, V.; Schiefloe, M.; et al. Perspectives for plant biology in space and analogue environments. npj Microgravity 2023, 9, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, A. Lessons from space. New Sci. 2022, 254, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C.A. Bioregenerative life-support systems. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1994, 60, 820S–824S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massa, G.D.; Dufour, N.F.; Carver, J.A.; Hummerick, M.E.; Wheeler, R.M.; Morrow, R.C.; Smith, T.M. VEG-01: Veggie hardware validation testing on the International Space Station. Open Agric. 2017, 2, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamran, M.; Auroux, L.; Johnson, K.; Lewsey, M.G. Optimising plant form and function for controlled environment agriculture in space and on earth. Mod. Agric. 2023, 1, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odeh, R.; Guy, C. Gardening for therapeutic people-plant interactions during long-duration space missions. Open Agric. 2017, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsche, R.; Haveman, N.; Massa, G.; Mickens, M.; Smith, T.; Wheeler, R.; Link, B.; Spencer, L. Space Crop Considerations for Human Exploration. Report/Patent Number: NASA/TM-20250001897, 1 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Massa, D.; Magán, J.J.; Montesano, F.F.; Tzortzakis, N. Minimizing water and nutrient losses from soilless cropping in southern Europe. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 241, 106395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.M.; Boles, H.O.; Spencer, L.E.; Poulet, L.; Romeyn, M.; Bunchek, J.M.; Fritsche, R.; Massa, G.D.; O’rOurke, A.; Wheeler, R.M. Supplemental food production with plants: A review of NASA research. Front. Astron. Space Sci. 2021, 8, 734343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dueck, T.; Kempkes, F.; Meinen, E.; Stanghellini, C. Choosing crops for cultivation in space. In Proceedings of the 46th International Conference on Environmental Systems, Vienna, Austria, 10–14 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zabel, P.; Zeidler, C.; Vrakking, V.; Dorn, M.; Schubert, D. Biomass Production of the EDEN ISS Space Greenhouse in Antarctica During the 2018 Experiment Phase. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunchek, J.M.; Hummerick, M.E.; Spencer, L.E.; Romeyn, M.W.; Young, M.; Morrow, R.C.; Mitchell, C.A.; Douglas, G.L.; Wheeler, R.M.; Massa, G.D. Pick-and-eat space crop production flight testing on the International Space Station. J. Plant Interact. 2024, 19, 2292220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izzo, L.G.; El Nakhel, C.; Rouphael, Y.; Proietti, S.; Paglialunga, G.; Moscatello, S.; Battistelli, A.; Iovane, M.; Romano, L.E.; De Pascale, S.; et al. Applying productivity and phytonutrient profile criteria in modelling species selection of microgreens as Space crops for astronaut consumption. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1210566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeyn, M.; Spencer, L.; Massa, G.; Wheeler, R. Crop readiness level (CRL): A scale to track progression of crop testing for space. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Environmental Systems (ICES) 2019, Boston, MA, USA, 7–11 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Crooker, K.D. Crop Selection in Controlled Ecological Life Support Systems. In Handbook of Life Support Systems for Spacecraft and Extraterrestrial Habitats; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, R.M.; Sager, J.C. Crop Production for Advanced Life Support Systems. Technical Reports. Paper 1. 2006. Available online: http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/nasatr/1 (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Koçkaya, E.S.; Un, C. Life of plants in space: A challenging mission for tiny greens in an everlasting darkness. Havacılık Ve Uzay Çalışmaları Derg. 2022, 2, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partida-Martínez, L.P.; Heil, M. The Microbe-Free Plant: Fact or Artifact? Front. Plant Sci. 2011, 2, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mermel, L.A. Infection prevention and control during prolonged human space travel. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 56, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porterfield, D.M. The biophysical limitations in physiological transport and exchange in plants grown in microgravity. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2002, 21, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, A.-L.; Sng, N.J.; Zupanska, A.K.; Krishnamurthy, A.; Schultz, E.R.; Ferl, R.J. Genetic dissection of the Arabidopsis spaceflight transcriptome: Are some responses dispensable for the physiological adaptation of plants to spaceflight? PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crabbé, A.; Nielsen-Preiss, S.M.; Woolley, C.M.; Barrila, J.; Buchanan, K.; McCracken, J.; Inglis, D.O.; Searles, S.C.; Nelman-Gonzalez, M.A.; Ott, C.M.; et al. Spaceflight enhances cell aggregation and random budding in Candida albicans. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e80677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.W.; Ott, C.M.; Zu Bentrup, K.H.; Ramamurthy, R.; Quick, L.; Porwollik, S.; Cheng, P.; McClelland, M.; Tsaprailis, G.; Radabaugh, T.; et al. Space flight alters bacterial gene expression and virulence and reveals a role for global regulator Hfq. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 16299–16304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raaijmakers, J.M.; Paulitz, T.C.; Steinberg, C.; Alabouvette, C.; Moënne-Loccoz, Y. The rhizosphere: A playground and battlefield for soilborne pathogens and beneficial microorganisms. Plant Soil 2009, 321, 341–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummerick, M.; Garland, J.; Bingham, G.; Sychev, V.; Podolsky, I. Microbiological analysis of Lada Vegetable Production Units (VPU) to define critical control points and procedures to ensure the safety of space grown vegetables. In Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Environmental Systems, Barcelona, Spain, 11–15 July 2010; p. 6255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, A.B.; Spern, C.J.; Khodadad, C.L.M.; Hummerick, M.E.; Spencer, L.E.; Torres, J.; Finn, J.R.; Gooden, J.L.; Monje, O. Post-harvest cleaning, sanitization, and microbial monitoring of soilless nutrient delivery systems for sustainable space crop production. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1308150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, A.A.; Schuerger, A.C.; Barford, C.; Mitchell, R. Engineering strategies for the design of plant nutrient delivery systems for use in space: Approaches to countering microbiological contamination. Adv. Space Res. 1996, 18, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horneck, G.; Klaus, D.M.; Mancinelli, R.L. Space microbiology. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2010, 74, 121–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Jeffery, D.W. Machine Learning Model Stability for Sub-Regional Classification of Barossa Valley Shiraz Wine Using A-TEEM Spectroscopy. Foods 2024, 13, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasanna, N.L.; Choudhary, S.; Kumar, S.; Choudhary, M.; Meena, P.K.; Samreen; Saloni, S.; Ghanghas, R. Advances in plant disease diagnostics and surveillance—A review. Plant Cell Biotechnol. Mol. Biol. 2024, 25, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, W.C.; Oubre, C.; Mehta, S.K.; Ott, C.M.; Pierson, D.L. Preventing infectious diseases in spacecraft and space habitats. In Modeling the Transmission and Prevention of Infectious Disease; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kordyum, E.; Hedukha, O.; Artemeko, O.; Ivanenko, G. Seed and vegetative propagation of plants in microgravity. J. Deep Space Explor. 2020, 7, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Villanueva, M.; Wong, M.; Lu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, H. Interplay of space radiation and microgravity in DNA damage and DNA damage response. npj Microgravity 2017, 3, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, A.R.; Meyers, A.D.; Richardson, B.; Richards, J.T.; Richards, S.E.; Neelam, S.; Levine, H.G.; Cameron, M.J.; Zhang, Y. Simulated galactic cosmic ray exposure activates dose-dependent DNA repair response and down regulates glucosinolate pathways in arabidopsis seedlings. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1284529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, L.E.; van Loon, J.J.W.A.; Izzo, L.G.; Iovane, M.; Aronne, G. Effects of altered gravity on growth and morphology in Wolffia globosa implications for bioregenerative life support systems and space-based agriculture. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musgrave, M.E.; Kuang, A.; Matthews, S.W. Plant reproduction during spaceflight: Importance of the gaseous environment. Planta 1997, 203 (Suppl. S1), S177–S184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, A.; Musgrave, M.E.; Matthews, S.W.; Cummins, D.B.; Tucker, S.C. Pollen and ovule development in Arabidopsis thaliana under spaceflight conditions. Am. J. Bot. 1995, 82, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalchuk, O.; Baulch, J.E. Epigenetic changes and nontargeted radiation effects—Is there a link? Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2008, 49, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belli, M.; Tabocchini, M.A. Ionizing radiation-induced epigenetic modifications and their relevance to radiation protection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laanen, P.; Saenen, E.; Mysara, M.; Van de Walle, J.; Van Hees, M.; Nauts, R.; Van Nieuwerburgh, F.; Voorspoels, S.; Jacobs, G.; Cuypers, A.; et al. Changes in DNA methylation in Arabidopsis thaliana plants exposed over multiple generations to gamma radiation. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 611783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandler, J.O.; Haas, F.B.; Khan, S.; Bowden, L.; Ignatz, M.; Enfissi, E.M.A.; Gawthrop, F.; Griffiths, A.; Fraser, P.D.; Rensing, S.A.; et al. Rocket science: The effect of spaceflight on germination physiology, ageing, and transcriptome of Eruca sativa seeds. Life 2020, 10, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Link, B.M.; Busse, J.S.; Stankovic, B. Seed-to-seed-to-seed growth and development of Arabidopsis in microgravity. Astrobiology 2014, 14, 866–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhos, E.; Golubkina, N.; Antoshkina, M.; Kondratyeva, I.; Koshevarov, A.; Shkaplerov, A.; Zavarykina, T.; Nechitailo, G.; Caruso, G. Effect of spaceflight on tomato seed quality and biochemical characteristics of mature plants. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Sng, N.J.; LeFrois, C.E.; Paul, A.-L.; Ferl, R.J. Epigenomics in an extraterrestrial environment: Organ-specific alteration of DNA methylation and gene expression elicited by spaceflight in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, R.; Kruse, C.P.S.; Johnson, C.; Saravia-Butler, A.; Fogle, H.; Chang, H.-S.; Trane, R.M.; Kinscherf, N.; Villacampa, A.; Manzano, A.; et al. Meta-analysis of the space flight and microgravity response of the Arabidopsis plant transcriptome. npj Microgravity 2023, 9, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olanrewaju, G.O.; Haveman, N.J.; Naldrett, M.J.; Paul, A.-L.; Ferl, R.J.; Wyatt, S.E. Integrative transcriptomics and proteomics profiling of Arabidopsis thaliana elucidates novel mechanisms underlying spaceflight adaptation. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1260429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gòdia, F.; Albiol, J.; Montesinos, J.; Pérez, J.; Creus, N.; Cabello, F.; Mengual, X.; Montras, A.; Lasseur, C. MELISSA: A loop of interconnected bioreactors to develop life support in space. J. Biotechnol. 2002, 99, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Micco, V.; Amitrano, C.; Mastroleo, F.; Aronne, G.; Battistelli, A.; Carnero-Diaz, E.; De Pascale, S.; Detrell, G.; Dussap, C.-G.; Ganigué, R.; et al. Plant and microbial science and technology as cornerstones to Bioregenerative Life Support Systems in space. npj Microgravity 2023, 9, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, C.L.; Concepcion, R.; Bandala, A. Identifying the Future Trends of Bioregenerative Life Support Systems for Space Exploration. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 15th International Conference on Humanoid, Nanotechnology, Information Technology, Communication and Control, Environment, and Management (HNICEM), Coron, Palawan, Philippines, 19–23 November 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, R.N. Detection of adsorbed water and hydroxyl on the Moon. Science 2009, 326, 562–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand, M.; Tartèse, R.; Barnes, J.J. Understanding the origin and evolution of water in the Moon through lunar sample studies. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2014, 372, 20130254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Lucey, P.G.; Milliken, R.E.; Hayne, P.O.; Fisher, E.; Williams, J.-P.; Hurley, D.M.; Elphic, R.C. Direct evidence of surface exposed water ice in the lunar polar regions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 8907–8912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, G.B.; Larson, W.E. Progress made in lunar in situ resource utilization under NASA’s exploration technology and development program. J. Aerosp. Eng. 2013, 26, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farina, D.; Machrafi, H.; Queeckers, P.; Minetti, C.; Iorio, C.S. Water Recuperation from Regolith at Martian, Lunar & Micro-Gravity during Parabolic Flight. Aerospace 2024, 11, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisler, J.D.; Newville, T.M.; Chen, F.; Clark, B.C.; Schneegurt, M.A. Bacterial growth at the high concentrations of magnesium sulfate found in Martian soils. Astrobiology 2012, 12, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verostko, C.E.; Edeen, M.A.; Packham, N.J.C. A hybrid regenerative water recovery system for lunar/Mars life support applications. SAE Trans. 1992, 101, 937–944. [Google Scholar]

- Amalfitano, S.; Levantesi, C.; Copetti, D.; Stefani, F.; Locantore, I.; Guarnieri, V.; Lobascio, C.; Bersani, F.; Giacosa, D.; Detsis, E.; et al. Water and microbial monitoring technologies towards the near future space exploration. Water Res. 2020, 177, 115787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polese, D.; Maiolo, L.; Pazzini, L.; Fortunato, G.; Mattoccia, A.; Medaglia, P.G. Wireless sensor networks and flexible electronics as innovative solution for smart greenhouse monitoring in long-term space missions. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 5th International Workshop on Metrology for AeroSpace (MetroAeroSpace), Turin, Italy, 19–21 June 2019; pp. 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidler, C.; Zabel, P.; Vrakking, V.; Dorn, M.; Bamsey, M.; Schubert, D.; Ceriello, A.; Fortezza, R.; De Simone, D.; Stanghellini, C.; et al. The plant health monitoring system of the EDEN ISS space greenhouse in Antarctica during the 2018 experiment phase. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingham, G.; Jones, S.; Or, D.; Podolski, I.; Levinskikh, M.; Sytchov, V.; Ivanova, T.; Kostov, P.; Sapunova, S.; Dandolov, I.; et al. Microgravity effects on water supply and substrate properties in porous matrix root support systems. Acta Astronaut. 2000, 47, 839–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatch, T.; Wasserman, M.; McQuillen, J.; Weislogel, M. Plant water management in microgravity. In Proceedings of the 51st International Conference on Environmental Systems, Saint Paul, MN, USA, 10–14 July 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, S.B.; Or, D. A capillary-driven root module for plant growth in microgravity. Adv. Space Res. 1998, 22, 1407–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pruitt, J.M.; Carter, L.; Bagdigian, R.M.; Kayatin, M.J. Upgrades to the ISS water recovery system. In Proceedings of the 45th International Conference on Environmental Systems, Bellevue, WA, USA, 12–16 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Carotti, L.; Pistillo, A.; Zauli, I.; Meneghello, D.; Martin, M.; Pennisi, G.; Gianquinto, G.; Orsini, F. Improving water use efficiency in vertical farming: Effects of growing systems, far-red radiation and planting density on lettuce cultivation. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 285, 108365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z. Improvement and optimization of spacecraft environmental control and life support systems. Theor. Nat. Sci. 2024, 30, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.; Zhu, G.; Liu, B.; Su, Q.; Deng, S.; Yang, L.; Liu, G.; Dong, C.; Wang, M.; Liu, H. The water treatment and recycling in 105-day bioregenerative life support experiment in the Lunar Palace 1. Acta Astronaut. 2017, 140, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Guo, S.; Zhao, P.; Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Bian, Q. Research on lettuce growth technology onboard Chinese Tiangong II Spacelab. Acta Astronaut. 2018, 144, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Li, S.; Liu, H.; Hu, D. Reliability and lifetime estimation of bioregenerative life support system based on 370-day closed human experiment of lunar palace 1 and Monte Carlo simulation. Acta Astronaut. 2023, 202, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porterfield, D.M.; Tulodziecki, D.; Wheeler, R.; Cross, M.K.D.; Monje, O.; Rothschild, L.J.; Barker, R.J.; Schwertz, H.; Collicott, S.; Dutta, S. Critical investments in bioregenerative life support systems for bioastronautics and sustainable lunar exploration. npj Microgravity 2025, 11, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Zheng, W.; Liu, F.; Ding, K.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, J.; Xu, D.; Zhang, T.; Zheng, H. Biological culture module for plant research from seed-to-seed on the Chinese Space Station. Life Sci. Space Res. 2024, 42, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; Zhou, A.; Shen, S.-L. Prediction of long-term water quality using machine learning enhanced by Bayesian optimisation. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 318, 120870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmarathne, G.; Abekoon, A.; Bogahawaththa, M.; Alawatugoda, J.; Meddage, D.P.P. A review of machine learning and internet-of-things on the water quality assessment: Methods, applications and future trends. Results Eng. 2025, 26, 105182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasenstein, K.H.; Miklave, N.M. Hydroponics for plant cultivation in space–a white paper. Life Sci. Space Res. 2024, 43, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugbee, B.G.; Salisbury, F.B. Controlled environment crop production: Hydroponic vs. lunar regolith. In Lunar Base Agriculture: Soils for Plant Growth; American Society of Agronomy: Madison, WI, USA, 1989; pp. 107–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, D.W.; Henninger, D.L. Use of lunar regolith as a substrate for plant growth. Adv. Space Res. 1994, 14, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caporale, A.G.; Paradiso, R.; Liuzzi, G.; Palladino, M.; Amitrano, C.; Arena, C.; Arouna, N.; Verrillo, M.; Cozzolino, V.; De Pascale, S.; et al. Green compost amendment improves potato plant performance on Mars regolith simulant as substrate for cultivation in space. Plant Soil 2023, 486, 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neilson, B.N.; Craig, C.M.; Altman, G.C.; Travis, A.T.; Vance, J.A.; Klein, M.I. Can the biophilia hypothesis be applied to long-duration human space flight? A mini-review. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 703766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behera, S.; Mahanwar, P.A. Superabsorbent polymers in agriculture and other applications: A review. Polym. Technol. Mater. 2020, 59, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, S.; Chen, G. Hydrogels as water and nutrient reservoirs in agricultural soil: A comprehensive review of classification, performance, and economic advantages. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 24653–24685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichler, A.; Hadland, N.; Pickett, D.; Masaitis, D.; Handy, D.; Perez, A.; Batcheldor, D.; Wheeler, B.; Palmer, A. Challenging the agricultural viability of Martian regolith simulants. Icarus 2021, 354, 114022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duri, L.G.; Caporale, A.G.; Rouphael, Y.; Vingiani, S.; Palladino, M.; De Pascale, S.; Adamo, P. The potential for lunar and martian regolith simulants to sustain plant growth: A multidisciplinary overview. Front. Astron. Space Sci. 2022, 8, 747821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, E.; Kim, K.-H.; Kwon, E.E. Biochar as a tool for the improvement of soil and environment. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1324533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyrusson, F. Hydrogels improve plant growth in mars analog conditions. Front. Astron. Space Sci. 2021, 8, 729278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, C.; Xie, G.; Han, Y.; Peng, M. Biochar improves lettuce seedling growth by influencing the nutrient content of simulated lunar soil. iScience 2025, 28, 113327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonangelo, J.A.; Culman, S.; Zhang, H. Comparative analysis and prediction of cation exchange capacity via summation: Influence of biochar type and nutrient ratios. Front. Soil Sci. 2024, 4, 1371777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.B.; Or, D.; Heinse, R.; Tuller, M. Beyond Earth: Designing root zone environments for reduced gravity conditions. Vadose Zone J. 2012, 11, vzj2011-0081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Or, D.; Phutane, S.; Dechesne, A. Extracellular polymeric substances affecting pore-scale hydrologic conditions for bacterial activity in unsaturated soils. Vadose Zone J. 2007, 6, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adcock, C.T.; Hausrath, E.M.; Rampe, E.B.; Cruz, V.; Wright, L. Perchlorate Recovery by Dissolution from Martian Soil Simulants: Implications for Human Exploration of Mars. In Proceedings of the 53rd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, The Woodlands, TX, USA, 7–11 March 2022; Volume 2678, p. 1667. [Google Scholar]

- Coufalík, P.; Stavrakakis, H.-A.; Argyrou, D. Chemical analysis of Antarctic regolith and lunar regolith simulant as prospective substrates for experiments with plants. Czech Polar Rep. 2024, 14, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, R.A.; Kanwar, M.K.; dos Reis, A.R.; Ali, B. Heavy metal toxicity in plants: Recent insights on physiological and molecular aspects. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 830682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, D.B.; Zuberer, D.A.; Hubbell, D.H. Microbiological Considerations for Lunar-Derived Soils. In Lunar Base Agriculture: Soils for Plant Growth; American Society of Agronomy: Madison, WI, USA, 1989; pp. 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, N.; Liu, D.; Harandi, B.F.; Kounaves, S.P. Microbial growth in Martian soil simulants under Terrestrial conditions: Guiding the search for life on Mars. Astrobiology 2022, 22, 1210–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.; Taylor, L.A.; DiGiuseppe, M.; Heilbronn, L.H.; Sanders, G.; Zeitlin, C.J. Radiation shielding properties of lunar regolith and regolith simulant. LPI Contrib. 2008, 1415, 2028. [Google Scholar]

- Meurisse, A.; Cazzaniga, C.; Frost, C.; Barnes, A.; Makaya, A.; Sperl, M. Neutron radiation shielding with sintered lunar regolith. Radiat. Meas. 2020, 132, 106247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomašić, M.; Zgorelec, Ž.; Jurišić, A.; Kisić, I. Cation exchange capacity of dominant soil types in the Republic of Croatia. J. Cent. Eur. Agric. 2013, 14, 937–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporale, A.G.; Palladino, M.; De Pascale, S.; Duri, L.G.; Rouphael, Y.; Adamo, P. How to make the Lunar and Martian soils suitable for food production-assessing the changes after manure addition and implications for plant growth. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 325, 116455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weaver, A.R.; Kissel, D.E.; Chen, F.; West, L.T.; Adkins, W.; Rickman, D.; Luvall, J.C. Mapping Soil pH Buffering Capacity of Selected Fields in the Coastal Plain. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2004, 68, 662–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schediwy, S.; Rosman, K.J.R.; de Laeter, J.R. Isotope fractionation of cadmium in lunar material. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2006, 243, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mititelu, M.; Neacșu, S.M.; Busnatu, Ș.S.; Scafa-Udriște, A.; Andronic, O.; Lăcraru, A.-E.; Ioniță-Mîndrican, C.-B.; Lupuliasa, D.; Negrei, C.; Olteanu, G. Assessing heavy metal contamination in food: Implications for human health and environmental safety. Toxics 2025, 13, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alawadhi, N.; Abass, K.; Khaled, R.; Osaili, T.M.; Semerjian, L. Heavy metals in spices and herbs from worldwide markets: A systematic review and health risk assessment. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 362, 124999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molaro, J.L.; Walsh, K.J.; Jawin, E.R.; Ballouz, R.-L.; Bennett, C.A.; DellaGiustina, D.N.; Golish, D.R.; D’aubigny, C.D.; Rizk, B.; Schwartz, S.R.; et al. In situ evidence of thermally induced rock breakdown widespread on Bennu’s surface. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrier, W.D., III; Olhoeft, G.R.; Mendell, W. Physical properties of the lunar surface. In Lunar Sourcebook, a User’s Guide to Moon; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991; pp. 475–594. [Google Scholar]

- Cannon, K.M.; Britt, D.T.; Smith, T.M.; Fritsche, R.F.; Batcheldor, D. Mars global simulant MGS-1: A Rocknest-based open standard for basaltic martian regolith simulants. Icarus 2019, 317, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fussy, A.; Papenbrock, J. An overview of soil and soilless cultivation techniques—Chances, challenges and the neglected question of sustainability. Plants 2022, 11, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fackrell, L.E.; Humphrey, S.; Loureiro, R.; Palmer, A.G.; Long-Fox, J. Overview and recommendations for research on plants and microbes in regolith-based agriculture. npj Sustain. Agric. 2024, 2, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuerger, A.C.; Ming, D.W.; Newsom, H.E.; Ferl, R.J.; McKay, C.P. Near-term lander experiments for growing plants on Mars: Requirements for information on chemical and physical properties of Mars regolith. Life Support Biosph. Sci. 2002, 8, 137–147. [Google Scholar]

- Karl, D.; Cannon, K.M.; Gurlo, A. Review of space resources processing for Mars missions: Martian simulants, regolith bonding concepts and additive manufacturing. Open Ceram. 2022, 9, 100216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slabic, A.; Gruener, J.E.; Kovtun, R.N.; Rickman, D.L.; Sibille, L.; Oravec, H.A.; Edmunson, J.; Keprta, S. Lunar Regolith Simulant User’s Guide: Revision A; No. NASA/TM-20240011783; National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA): Moffett Field, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Hu, H.; Yang, M.-F.; Pei, Z.-Y.; Zhou, Q.; Ren, X.; Liu, B.; Liu, D.; Zeng, X.; Zhang, G.; et al. Characteristics of the lunar samples returned by the Chang’E-5 mission. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2022, 9, nwab188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Y.; Wu, H.; Chai, S.; Yang, W.; Ruan, R.; Zhao, Q. Development and characterization of the PolyU-1 lunar regolith simulant based on Chang’e-5 returned samples. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2024, 34, 1317–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adal, Y. The impact of beneficial micro-organisms on soil vitality: A review. Front. Environ. Microbiol. 2024, 10, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehle, A.P.; Brumwell, S.L.; Seto, E.P.; Lynch, A.M.; Urbaniak, C. Microbial applications for sustainable space exploration beyond low Earth orbit. npj Microgravity 2023, 9, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, A.C.J.; Papic, A.; Nikolic, I.; Brazier, F. Stoichiometric model of a fully closed bioregenerative life support system for autonomous long-duration space missions. Front. Astron. Space Sci. 2023, 10, 1198689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschner, H. Marschner’s Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.Y.; Rahman, A.; Azam, H.; Kim, H.S.; Kwon, M.J. Characterizing nutrient uptake kinetics for efficient crop production during Solanum lycopersicum var. cerasiforme Alef. growth in a closed indoor hydroponic system. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenhar, I.; Harikumar, A.; Trujillo, M.R.P.; Zhao, Z.; Lin, Q.; Setyawati, M.I.; Tan, D.; He, J.; Herrmann, I.; Ng, K.W.; et al. Nitrogen ionome dynamics on leafy vegetables in tropical climate. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strayer, R.F.; Atkinson, C.F. An overview: Recycling nutrients from crop residues for space applications. Compost Sci. Util. 1997, 5, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeelen, T.; Leys, N.; Ganigué, R.; Mastroleo, F. Development of Nitrogen Recycling Strategies for Bioregenerative Life Support Systems in Space. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 700810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, C.; Parker, A.; Jefferson, B.; Cartmell, E. The characterization of feces and urine: A review of the literature to inform advanced treatment technology. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 45, 1827–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, H.C.; Cao, H.T.; Hoang, N.B.; Nghiem, L.D. Reverse osmosis treatment of condensate from ammonium nitrate production: Insights into membrane performance. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 106457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Li, C.; Chen, G. A comprehensive review on wastewater nitrogen removal and its recovery processes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, P.S.; Ahmad, N.A.; Lim, J.W.; Liang, Y.Y.; Kang, H.S.; Ismail, A.F.; Arthanareeswaran, G. Microalgae-enabled wastewater remediation and nutrient recovery through membrane photobioreactors: Recent achievements and future perspective. Membranes 2022, 12, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoehn, A.; Scovazzo, P.; Stodieck, L.S.; Clawson, J.; Kalinowski, W.; Rakow, A.; Simmons, D.; Heyenga, A.G.; Kliss, M.H. Microgravity Root Zone Hydration Systems; SAE Technical Paper; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komatsu, S.; Misaki, H.; Zhu, W.; Yamaguchi, H.; Hitachi, K.; Tsuchida, K.; Higashitani, A. The Growth of Soybean (Glycine max) Under Salt Stress Is Modulated in Simulated Microgravity Conditions. Cells 2025, 14, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Or, D.; Tuller, M.; Jones, S.B. Liquid behavior in partially saturated porous media under variable gravity. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2009, 73, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, P.; Hughes, J.; Gamage, T.V.; Knoerzer, K.; Ferlazzo, M.L.; Banati, R.B. Long term food stability for extended space missions: A review. Life Sci. Space Res. 2022, 32, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Rising, H.H.; Majji, M.; Brown, R.D. Long-term space nutrition: A scoping review. Nutrients 2021, 14, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M.; Douglas, G.; Perchonok, M. Developing the NASA food system for long-duration missions. J. Food Sci. 2011, 76, R40–R48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorhies, A.A.; Lorenzi, H.A. The challenge of maintaining a healthy microbiome during long-duration space missions. Front. Astron. Space Sci. 2016, 3, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Zheng, L.; Xie, B.; Ma, L.; Jia, M.; Xie, C.; Hu, C.; Ulbricht, M.; Wei, Y. Sustainable wastewater treatment and reuse in space. J. Environ. Sci. 2024, 146, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaczmarzyk, M.; Gawronski, M.; Piatkowski, G. Global database of direct solar radiation at the Moon’s surface for lunar engineering purposes. E3S Web Conf. 2018, 49, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuerger, A.C.; Moores, J.E.; Smith, D.J.; Reitz, G. A lunar microbial survival model for predicting the forward contamination of the Moon. Astrobiology 2019, 19, 730–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landis, G.A.; Appelbaum, J. Design considerations for Mars photovoltaic system. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Photovoltaic Specialists, Kissimmee, FL, USA, 21–25 May 1990; Volume 1, pp. 1263–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindra, B. Forecasting solar radiation during dust storms using deep learning. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1808.10854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopp, G.; Lean, J.L. A new, lower value of total solar irradiance: Evidence and climate significance. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2011, 38, L01706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelbaum, J.; Flood, D.J. Solar radiation on Mars. Sol. Energy 1990, 45, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, L.; Nguyen, T.-T.-A.; Brégard, A.; Pepin, S.; Dorais, M. Optimizing light use efficiency and quality of indoor organically grown leafy greens by using different lighting strategies. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, T.; Dunn, B. LED Grow Lights for Plant Production; Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Service: Oklahoma City, OK, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Murchie, E.H.; Niyogi, K.K. Manipulation of Photoprotection to Improve Plant Photosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 2011, 155, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCree, K.J. The action spectrum, absorptance and quantum yield of photosynthesis in crop plants. Agric. Meteorol. 1971, 9, 191–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugbee, B.; Monje, O. The optimization of crop productivity: Theory and validation. Bioscience 1992, 42, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petro, A. Surviving and Operating Through the Lunar Night. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Aerospace Conference, Big Sky, MT, USA, 7–14 March 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayatsu, K.; Hareyama, M.; Kobayashi, S.; Yamashita, N.; Miyajim, M.; Sakurai, K.; Hasebe, N. Radiation Doses for Human Exposed to Galactic Cosmic Rays and Their Secondary Products on the Lunar Surface. Biol. Sci. Space 2008, 22, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapp, D. Radiation Effects and Shielding Requirements in Human Missions to the Moon and Mars. Int. J. Mars Sci. Explor. 2006, 2, 46–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Califar, B.; Tucker, R.; Cromie, J.; Sng, N.; Schmitz, R.A.; Callaham, J.A.; Barbazuk, B.; Paul, A.-L.; Ferl, R.J. Approaches for Surveying Cosmic Radiation Damage in Large Populations of Arabidopsis thaliana Seeds—Antarctic Balloons and Particle Beams. Gravitational Space Res. 2020, 6, 54–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chancellor, J.C.; Scott, G.B.I.; Sutton, J.P. Space Radiation: The Number One Risk to Astronaut Health beyond Low Earth Orbit. Life 2014, 4, 491–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Richards, J.T.; Feiveson, A.H.; Richards, S.E.; Neelam, S.; Dreschel, T.W.; Plante, I.; Hada, M.; Wu, H.; Massa, G.D.; et al. Response of Arabidopsis thaliana and Mizuna Mustard Seeds to Simulated Space Radiation Exposures. Life 2022, 12, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J.T.; Spencer, L.E.; Torres, J.J.; Fischer, J.A.; Hada, M.; Plante, I.; Feiveson, A.H.; Wu, H.; Massa, G.D.; Levine, H.G.; et al. Impact of Space Radiation on Plants: From Arabidopsis thaliana to Crops. In Proceedings of the NASA 2021 HRP Investigators’ Workshop, Virtual, 1 February 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Vasavada, A.R.; Paige, D.A.; Wood, S.E. Near-surface temperatures on Mercury and the Moon and the stability of polar ice deposits. Icarus 1999, 141, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatla, S.C.; Lal, M.A. Plant Physiology, Development and Metabolism; Springer Nature: Durham, NC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteith, J.; Unsworth, M. Principles of Environmental Physics: Plants, Animals, and the Atmosphere; Acadamic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, S.J.; Blundell, K.M. ″Earth′s atmosphere. In Concepts in Thermal Physics; Oxford Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroz, V.I. Chemical composition of the atmosphere of Mars. Adv. Space Res. 1998, 22, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubrin, R.; Wagner, R.; McKay, C.P. The case for Mars: The plan to settle the red planet and why we must. Nature 1996, 383, 780. [Google Scholar]

- Viúdez-Moreiras, D.; Zorzano, M.-P.; Lemmon, M.T.; Fairén, A.G.; Saiz-Lopez, A.; Smith, M.D. Ultraviolet and biological effective dose observations at Gale Crater, Mars. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2426611122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosadegh, H.; Trivellini, A.; Ferrante, A.; Lucchesini, M.; Vernieri, P.; Mensuali, A. Applications of UV-B lighting to enhance phenolic accumulation of sweet basil. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 229, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Callaham, J.B.; Reyes, M.; Stasiak, M.; Riva, A.; Zupanska, A.K.; Dixon, M.A.; Paul, A.-L.; Ferl, R.J. Dissecting low atmospheric pressure stress: Transcriptome responses to the components of hypobaria in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busch, F.A.; Ainsworth, E.A.; Amtmann, A.; Cavanagh, A.P.; Driever, S.M.; Ferguson, J.N.; Kromdijk, J.; Lawson, T.; Leakey, A.D.B.; Matthews, J.S.A.; et al. A guide to photosynthetic gas exchange measurements: Fundamental principles, best practice and potential pitfalls. Plant. Cell Environ. 2024, 47, 3344–3364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, C.P.R.; Unnikrishnan, V. Stability of the Liquid Water Phase on Mars: A Thermodynamic Analysis Considering Martian Atmospheric Conditions and Perchlorate Brine Solutions. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 9391–9397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hibbitts, C.; Grieves, G.; Poston, M.; Dyar, M.D.; Alexandrov, A.; Johnson, M.; Orlando, T. Thermal stability of water and hydroxyl on the surface of the Moon from temperature-programmed desorption measurements of lunar analog materials. Icarus 2011, 213, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, N.X.; Dauphas, N.; Zhang, Z.J.; Hopp, T.; Sarantos, M. Lunar soil record of atmosphere loss over eons. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadm7074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corey, K.A.; Fowler, P.A.; Wheeler, R.M. Plant responses to rarified atmospheres. In Mars Greenhouses: Concepts and Challenges; Proceedings from a 1999 Workshop, NASA Kennedy Space Center: Cocoa Beach, FL, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lembo, S.; Niedrist, G.; El Omari, B.; Illmer, P.; Praeg, N.; Meul, A.; Dainese, M. Short-term impact of low air pressure on plants’ functional traits. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0317590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Hou, M. Acquired thermotolerance in plants. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2012, 111, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierson, D.L. Microbial Contamination in the Spacecraft. Gravit. Space Biol. Bull. 2001, 14, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Rygalov, V.Y.; Fowler, P.A.; Wheeler, R.M.; Bucklin, R.A. Water cycle and its management for plant habitats at reduced pressures. Habitation 2004, 10, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J.T.; Corey, K.A.; Paul, A.-L.; Ferl, R.J.; Wheeler, R.M.; Schuerger, A.C. Exposure of Arabidopsis thaliana to hypobaric environments: Implications for low-pressure bioregenerative life support systems for human exploration missions and terraforming on Mars. Astrobiology 2006, 6, 851–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, J.Z. Plant biology in reduced gravity on the Moon and Mars. Plant Biol. 2014, 16, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, E.M.; Hijazi, H.; Bennett, M.J.; Vissenberg, K.; Swarup, R. New insights into root gravitropic signalling. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 2155–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, A.-L.; E Amalfitano, C.; Ferl, R.J. Plant growth strategies are remodeled by spaceflight. BMC Plant Biol. 2012, 12, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janmaleki, M.; Pachenari, M.; Seyedpour, S.M.; Shahghadami, R.; Sanati-Nezhad, A. Impact of simulated microgravity on cytoskeleton and viscoelastic properties of endothelial cell. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Yang, X.; Tian, R.; Li, Y.; Wang, C.; Fan, Y.; Sun, L. Cells respond to space microgravity through cytoskeleton reorganization. FASEB J. 2022, 36, e22114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nijhuis, J.; Schmidt, S.; Tran, N.N.; Hessel, V. Microfluidics and macrofluidics in space: ISS-proven fluidic transport and handling concepts. Front. Space Technol. 2022, 2, 779696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, D.; Jian, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, G. Plant gravitropism and signal conversion under a stress environment of altered gravity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoson, T. Plant growth and morphogenesis under different gravity conditions: Relevance to plant life in space. Life 2014, 4, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronne, G.; Muthert, L.W.F.; Izzo, L.G.; Romano, L.E.; Iovane, M.; Capozzi, F.; Manzano, A.; Ciska, M.; Herranz, R.; Medina, F.; et al. A novel device to study altered gravity and light interactions in seedling tropisms. Life Sci. Space Res. 2022, 32, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacayurin, C.R.; De Chavez, J.C.; Lansangan, M.C.; Lucas, C.; Villanueva, J.J.; Relano, R.-J.; Romano, L.E.; Concepcion, R. Cloud-Enabled Multi-Axis Soilless Clinostat for Earth-Based Simulation of Partial Gravity and Light Interaction in Seedling Tropisms. Agriengineering 2025, 7, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clary, J.L.; France, C.S.; Lind, K.; Shi, R.; Alexander, J.; Richards, J.T.; Scott, R.S.; Wang, J.; Lu, X.-H.; Harrison, L. Development of an inexpensive 3D clinostat and comparison with other microgravity simulators using Mycobacterium marinum. Front. Space Technol. 2022, 3, 1032610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yingchutrakul, Y.; Tulyananda, T.; Krobthong, S. Comprehensive omics strategies for space agriculture development. Life Sci. Space Res. 2025, in press. [CrossRef]

- Hodges, R.R.; Hoffman, J.H.; Johnson, F.S. The lunar atmosphere. Icarus 1974, 21, 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, H.R. In-situ resource utilization–feasibility of the use of lunar soil to create structures on the moon via sintering based additive manufacturing technology. Aeronaut. Aerosp. Open Access J. 2018, 2, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forget, F. The present and past climates of planet Mars. EPJ Web Conf. 2009, 1, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, N.; Pauluhn, A. Exploring Earth’s magnetic field–Three make a Swarm. Spatium 2019, 2019, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, D.; Halekas, J.; Lin, R.; Frey, S.; Hood, L.; Acuña, M.; Binder, A. Global mapping of lunar crustal magnetic fields by Lunar Prospector. Icarus 2008, 194, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittelholz, A.; Johnson, C.L. The martian crustal magnetic field. Front. Astron. Space Sci. 2022, 9, 895362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramson, A.M.; Byrne, S.; Putzig, N.E.; Sutton, S.; Plaut, J.J.; Brothers, T.C.; Holt, J.W. Widespread excess ice in arcadia planitia, Mars. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2015, 42, 6566–6574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horányi, M.; Szalay, J.R.; Wang, X. The lunar dust environment: Concerns for Moon-based astronomy. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2024, 382, 20230075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilbao, J.; Miguel, A. Contribution to the study of UV-B solar radiation in Central Spain. Renew. Energy 2013, 53, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabel, P.; Bamsey, M.; Schubert, D.; Tajmar, M. Review and analysis of over 40 years of space plant growth systems. Life Sci. Space Res. 2016, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.T.P.; Knowling, M.; Tran, N.N.; Burgess, A.; Fisk, I.; Watt, M.; Escribà-Gelonch, M.; This, H.; Culton, J.; Hessel, V. Space farming: Horticulture systems on spacecraft and outlook to planetary space exploration. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 194, 708–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, R.M. NASA’ s contributions to vertical farming. In Proceedings of the XXXI International Horticultural Congress (IHC2022): International Symposium on Advances in Vertical Farming 1369, Angers, France, 14–20 August 2022; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boscheri, G.; Lobascio, C.; Lamantea, M.M.; Locantore, I.; Guarnieri, V.; Schubert, D. The EDEN ISS rack-like plant growth facility. In Proceedings of the 46th International Conference on Environmental Systems, Vienna, Austria, 10–14 July 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleisher, D.H.; Rodriguez, L.F.; Both, A.J.; Cavazzoni, J.; Ting, K.C. 5.11 Advanced Life Support Systems in Space. In CIGR Handbook of Agricultural Engineering Volume VI Information Technology; Chapter 5 Precision Agriculture; ASABE: St. Joseph, MI, USA, 2006; pp. 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantz, J.M.; Joly, R.J.; Mitchell, C.A. Intracanopy lighting reduces electrical energy utilization by closed cowpea stands. Life Support Biosph. Sci. 2001, 7, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Albright, L.D.; Both, A.J. Comparisons of Luminaires: Efficacies and System Design; Wisconsin University: Madison, WI, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, E.; Morales, A.; Harbinson, J.; Kromdijk, J.; Heuvelink, E.; Marcelis, L.F.M. Dynamic photosynthesis in different environmental conditions. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 2415–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pattison, P.M.; Tsao, J.Y.; Brainard, G.C.; Bugbee, B. LEDs for photons, physiology and food. Nature 2018, 563, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bula, R.J.; Ignatius, R.W. Providing controlled environments for plant growth in space. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Plant Production in Closed Ecosystems 440, Narita, Japan, 26–29 August 1996; pp. 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, M.; Ishikawa, Y.; Nagatomo, M.; Oshima, T.; Wada, H. Space agriculture for manned space exploration on mars. J. Space Technol. Sci. 2005, 21, 2_1–2_10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossati, L.; Ilstad, J. The future of embedded systems at ESA: Towards adaptability and reconfigurability. In Proceedings of the 2011 NASA/ESA Conference on Adaptive Hardware and Systems (AHS), San Diego, CA, USA, 6–9 June 2011; pp. 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metelli, G.; Lampazzi, E.; Pagliarello, R.; Garegnani, M.; Nardi, L.; Calvitti, M.; Gugliermetti, L.; Alessi, R.R.; Benvenuto, E.; Desiderio, A. Design of a modular controlled unit for the study of bioprocesses: Towards solutions for Bioregenerative Life Support Systems in space. Life Sci. Space Res. 2023, 36, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.M. Space Habitat Design Integration Issues; SAE Technical Paper; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabel, P.; Schubert, D.; Tajmar, M. Combination of Physico-Chemical Life Support Systems with Space Greenhouse Modules: A System Analysis. In Proceedings of the 43rd International Conference on Environmental Systems, Vail, Colorado, 14–18 July 2013; p. 3333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubek, D.J.; Whitmire, A.; Simon, M. Factors Impacting Habitable Volume Requirements for Long Duration Missions. In Proceedings of the Global Space Exploration Conference, GLEX-2012.05, Houston, TX, USA, 18–21 April 2012; Volume 3, p. x12276. [Google Scholar]

- Bayer, T. Planning for the un-plannable: Redundancy, fault protection, contingency planning and anomaly response for the mars reconnaissance oribiter mission. In Proceedings of the AIAA SPACE 2007 Conference & Exposition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 18–20 September 2007; p. 6109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirshorn, S.R.; Voss, L.D.; Bromley, L.K. Nasa Systems Engineering Handbook; NTRS—NASA Technical Reports Server: Cleveland, OH, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Blankenship, R.E.; Tiede, D.M.; Barber, J.; Brudvig, G.W.; Fleming, G.; Ghirardi, M.; Gunner, M.R.; Junge, W.; Kramer, D.M.; Melis, A.; et al. Comparing photosynthetic and photovoltaic efficiencies and recognizing the potential for improvement. Science 2011, 332, 805–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, R.K.M. Harvest index: A review of its use in plant breeding and crop physiology. Ann. Appl. Biol. 1995, 126, 197–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.-G.; Long, S.P.; Ort, D.R. Improving photosynthetic efficiency for greater yield. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2010, 61, 235–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Runkle, E.; Both, A.J. Greenhouse Energy Conservation Strategies; Michigan State University: East Lansing, MI, USA, 2011; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, J.T.; Malla, R.B. A Study of Layered Structural Configurations as Thermal and Impact Shielding of Lunar Habitats. In Proceedings of the Earth and Space 2021: Space Exploration, Utilization, Engineering, and Construction in Extreme Environments—Selected Papers from the 17th Biennial International Conference on Engineering, Science, Construction, and Operations in Challenging Environments, Online, 19–23 April 2021; pp. 1285–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, R.T.; Boudreau, M.-C.; van Iersel, M.W. Simulation of greenhouse energy use: An application of energy informatics. Energy Informatics 2018, 1, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babakhanova, S.; Baber, S.; Zazzera, F.B.; Hinterman, E.; Hoffman, J.; Kusters, J.; Lordos, G.C.; Lukic, J.; Maffia, F.; Maggiore, P.; et al. Mars garden an engineered greenhouse for a sustainable residence on mars. In Proceedings of the AIAA Propulsion and Energy 2019 Forum, Indianapolis, IN, USA, 19–22 August 2019; p. 4059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabel, P. Influence of crop cultivation conditions on space greenhouse equivalent system mass. CEAS Space J. 2021, 13, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahmoradi, J.; Maxwell, A.; Little, S.; Bradfield, Q.; Bakhtiyarov, S.; Roghanchi, P.; Hassanalian, M.; Gaier, J.R.; Ellis, S.; Hanks, N.; et al. The effects of Martian and lunar dust on solar panel efficiency and a proposed solution. In Proceedings of the AIAA Scitech 2020 Forum, Orlando, FL, USA, 6–10 January 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraskar, A.; Yoshimura, Y.; Nagasaki, S.; Hanada, T. Space solar power satellite for the Moon and Mars mission. J. Space Saf. Eng. 2022, 9, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefin, A.; Islam, M.T.; Rashid, F.; Mostakim, K.; Masuk, N.I.; Islam, H.I. A comprehensive review of nuclear-renewable hybrid energy systems: Status, operation, configuration, benefit, and feasibility. Front. Sustain. Cities 2021, 3, 723910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouroumova, L.; Witte, D.; Klootwijk, B.; Terwindt, E.; Van Marion, F.; Mordasov, D.; Vargas, F.C.; Heidweiller, S.; Géczi, M.; Kempers, M.; et al. Combined airborne wind and photovoltaic energy system for martian habitats. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.09506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, M.A.; Poston, D.I.; McClure, P.; Godfroy, T.; Sanzi, J.; Briggs, M.H. The Kilopower Reactor Using Stirling TechnologY (KRUSTY) nuclear ground test results and lessons learned. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Energy Conversion Engineering Conference, Cincinnati, Ohio, 9–11 July 2018; p. 4973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massa, G.D.; Wheeler, R.M.; Morrow, R.C.; Levine, H.G. Growth chambers on the International Space Station for large plants. In Proceedings of the VIII International Symposium on Light in Horticulture 1134, East Lansing, MI, USA, 22–26 May 2016; pp. 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbashov, N.N.; Barkova, A.A. Application of flywheel energy accumulators in agricultural robots. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 677, 32093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinokhodova, A.; Gushin, V.; Kuznetsova, P.; Yusupova, A. Crew Interaction in Extended Space Missions. Aerospace 2023, 10, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharad, R.A. Multitasking Agricultural Robot. Int. J. Sci. Res. Eng. Manag. 2025, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, S.S.; Khanal, A.; Sundaravadivel, P. Emerging technologies for automation in environmental sensing. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mount, F.; Woolford, B.J. Human Factors in Spaceflight. In International Encyclopedia of Ergonomics and Human Factors; CRC PRESS: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006; pp. 1956–1962. [Google Scholar]

- Fathallah, F.; Duraj, V. Small changes make big differences: The role of ergonomics in agriculture. Resour. Mag. 2017, 24, 12–13. Available online: https://elibrary.asabe.org/abstract.asp?aid=48600 (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- McDade, T.P. An Investigation of Adjustable Microgravity Workstation Anthropometrics Through Analyses of Neutral Body Posture and Lower Leg Muscular Fatigue Characteristics. Master’s Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1989. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:108550564 (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Zhu, M.; Sun, Z.; Lee, C. Soft modular glove with multimodal sensing and augmented haptic feedback enabled by materials’ multifunctionalities. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 14097–14110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, D.C. Gardening in Space: On the space shuttle Columbia, an experiment explores chemical growth without gravity—And the challenges of orbital science. Am. Sci. 2002, 90, 454–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinicke, C.; Poulet, L.; Dunn, J.; Meier, A. Crew self-organization and group-living habits during three autonomous, long-duration Mars analog missions. Acta Astronaut. 2021, 182, 160–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukumoto, H.; Shimoda, M.; Hoshino, S. The effects of different designs of indoor biophilic greening on psychological and physiological responses and cognitive performance of office workers. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0307934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angerer, M.; Pichler, G.; Angerer, B.; Scarpatetti, M.; Schabus, M.; Blume, C. From dawn to dusk—Mimicking natural daylight exposure improves circadian rhythm entrainment in patients with severe brain injury. Sleep 2022, 45, zsac065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landon, L.B.; Begerowski, S.R.; Roma, P.G.; Whiting, S.E.; Bell, S.T.; Massa, G.D. Sustaining the Merry Space farmer with pick-and-eat crop production. npj Microgravity 2025, 11, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, J.I.; Lisovsky, G.M. Man-Made Closed Ecological Systems; ESI B. Ser.; CRC Press: London, UK, 2002; Volume 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, A.M.; Li, W.; Calle, L.M.; Callahan, M.R. Investigation of biofilm formation and control for spacecraft-an early literature review. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Enviromental Systems, Boston, MA, USA, 7–11 July 2019. no. KSC-E-DAA-TN68829. [Google Scholar]

- Manuel, C.D.; Samardjieva, K. Culturable Bioaerosols Assessment in a Waste-Sorting Plant and UV-C Decontamination. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drews, F.A.; Wallace, J.; Benuzillo, J.; Markewitz, B.; Samore, M. Protocol adherence in the intensive care unit. Hum. Factors Ergon. Manuf. Serv. Ind. 2012, 22, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, S.F.; Podofillini, L.; Dang, V.N. Crew performance variability in human error probability quantification: A methodology based on behavioral patterns from simulator data. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part O J. Risk Reliab. 2021, 235, 637–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, D.L.; Barshi, I. Evidence Report: Risk of Performance Errors Due to Training Deficiencies; Report No. JSC-CN-35755; Johnson Space Center: Houston, TX, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, D.; Bandemegala, S.T.P.; Fountain, L.; Wright, H.C.; Moschopoulos, A.; Lantin, S.; Kainu, M.; Buchli, V. Sustainable crop cultivation in space analogs: A BRIDGES methodology perspective through SpaCEA cabinets. In Proceedings of the 53rd International Conference on Environmental Systems (ICES), Louisville, KY, USA, 21–25 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Soga, M.; Gaston, K.J.; Yamaura, Y. Gardening is beneficial for health: A meta-analysis. Prev. Med. Rep. 2017, 5, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botella, C.; Baños, R.M.; Etchemendy, E.; García-Palacios, A.; Alcañiz, M. Psychological countermeasures in manned space missions:‘EARTH’ system for the Mars-500 project. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 55, 898–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairburn, S.; Walker, S. ‘Sleeping with the Stars’—The Design of a Personal Crew Quarter for the International Space Station; SAE Technical Paper; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlacht, I.L.; Kolrep, H.; Daniel, S.; Musso, G. Impact of plants in isolation: The EDEN-ISS human factors investigation in Antarctica. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Applied Human Factors and Ergonomics, Washington, DC, USA, 24–28 July 2019; pp. 794–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauerer, M.; Schubert, D.; Zabel, P.; Bamsey, M.; Kohlberg, E.; Mengedoht, D. Initial survey on fresh fruit and vegetable preferences of Neumayer Station crew members: Input to crop selection and psychological benefits of space-based plant production. Open Agric. 2016, 1, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanta, T.K.; Mishra, A.K.; Mohanta, Y.K.; Al-Harrasi, A. Space breeding: The next-generation crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 771985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortimer, J.C.; Gilliham, M. SpaceHort: Redesigning plants to support space exploration and on-earth sustainability. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2022, 73, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupisella, M.L. Mitigating Adverse Effects of a Human Mission on Possible Martian Indigenous Ecosystems. In Proceedings of the Concepts and Approaches for Mars Exploration, Houston, TX, USA, 18–20 July 2000; p. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Affatato, V.; Conenna, M.; Roversi, D. The Ethics of Resource Extraction in Space: A Normative Essay. Preprints 2023, 2023110684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orasanu, J. Crew collaboration in space: A naturalistic decision-making perspective. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 2005, 76, B154–B163. [Google Scholar]

- Saint-Guillain, M.; Vanderdonckt, J.; Burny, N.; Pletser, V.; Vaquero, T.; Chien, S.; Karl, A.; Marquez, J.; Karasinski, J.; Wain, C.; et al. Enabling astronaut self-scheduling using a robust modelling and scheduling system (RAMS): A Mars analog use case. In Proceedings of the 16th Symposium on Advanced Space Technologies in Robotics and Automation, ASTRA 2022, ESAESTEC, Noordwijk, The Netherlands, 1–2 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, R.; Soma, T. To the farm, Mars, and beyond: Technologies for growing food in space, the future of long-duration space missions, and earth implications in English news media coverage. Front. Commun. 2022, 7, 1007567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Band, S.; Stechmann, F.; Unnikrishnan, M.; Attarha, S.; Heinicke, C.; Willig, A.; Foerster, A. Reliability Analysis of a Monitoring System for Extraterrestrial Habitats. In Proceedings of the 2024 20th International Conference on Wireless and Mobile Computing, Networking and Communications (WiMob), Paris, France, 21–23 October 2024; pp. 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-Y.; Li, X.; Feng, J.; Li, C.; Xiong, X.; Huang, H.-Z. Reliability analysis and optimization of multi-phased spaceflight with backup missions and mixed redundancy strategy. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2023, 237, 109373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, D.C.; Kurtz, S.R. Photovoltaic degradation rates—An analytical review. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 2013, 21, 12–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, D.C.; Kurtz, S.R.; VanSant, K.; Newmiller, J. Compendium of photovoltaic degradation rates. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 2016, 24, 978–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yedidi, K.; Tatapudi, S.; Mallineni, J.; Knisely, B.; Kutiche, J.; TamizhMani, G. Failure and degradation modes and rates of PV modules in a hot-dry climate: Results after 16 years of field exposure. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE 40th Photovoltaic Specialist Conference (PVSC), Denver, CO, USA, 8–13 June 2014; pp. 3245–3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köntges, M.; Kurtz, S.; Packard, C.; Jahn, U.; Berger, K.A.; Kato, K.; Friesen, T.; Liu, H.; Iseghem, M.K.; Wohlgemuth, J.; et al. Review of Failures of Photovoltaic Modules; IEA PVPS Task13 Performance and Reliability of Photovoltaic Systems Subtask 3.2; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2014; pp. 1–132. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, H.W. Diverse redundant systems for reliable space life support. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Environmental Systems, Bellevue, WA, USA, 12–16 July 2015. no. ICES-2015-047. [Google Scholar]

- Vílchez-Torres, M.K.; Oblitas-Cruz, J.F.; Castro-Silupu, W.M. Optimization of the replacement time for critical repairable components. Dyna 2020, 87, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, R.G. A systems approach to solder joint fatigue in spacecraft electronic packaging. J. Electron. Packag. 1991, 113, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poech, M.H. How materials behaviour affects power electronics reliability. In Proceedings of the 2010 6th International Conference on Integrated Power Electronics Systems, Nuremberg, Germany, 16–18 March 2010; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Dyke, S.J.; Marais, K.; Bilionis, I.; Werfel, J.; Malla, R. Strategies for the design and operation of resilient extraterrestrial habitats. In Proceedings of the Sensors and Smart Structures Technologies for Civil, Mechanical, and Aerospace Systems 2021, Online, 22–26 March 2021; Volume 11591, p. 1159105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monje, O.; Richards, J.T.; Carver, J.A.; Dimapilis, D.I.; Levine, H.G.; Dufour, N.F.; Onate, B.G. Hardware Validation of the Advanced Plant Habitat on ISS: Canopy Photosynthesis in Reduced Gravity. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aven, T. On how to deal with deep uncertainties in a risk assessment and management context. Risk Anal. 2013, 33, 2082–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulet, L.; Fontaine, J.-P.; Dussap, C.-G. Plants response to space environment: A comprehensive review including mechanistic modelling for future space gardeners. Bot. Lett. 2016, 163, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shortridge, J.; Aven, T.; Guikema, S. Risk assessment under deep uncertainty: A methodological comparison. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2017, 159, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cromwell, R.L.; Huff, J.L.; Simonsen, L.C.; Patel, Z.S. Earth-based research analogs to investigate space-based health risks. New Space 2021, 9, 204–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, D.A. Homo sapiens—A species not designed for space flight: Health risks in low earth orbit and beyond, including potential risks when traveling beyond the geomagnetic field of earth. Life 2023, 13, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chodas, M.; Masterson, R.; de Weck, O. Addressing Deep Uncertainty in Space System Development through Model-based Adaptive Design. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Aerospace Conference, Big Sky, MT, USA, 7–14 March 2020; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srimal, W.; Siraj, M.; Anjum, R.; Ahmed, M.R. Towards Sustainable Future: A Review of Emerging Technologies in Controlled Environment Agriculture. Mitteilungen Klosterneubg. 2024, 42, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Wang, L.; Li, F.; Liu, J. Model Embedded DRL for Intelligent Greenhouse Control. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.00020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.H. Controlled Environment agriculture in deserts, tropics and temperate regions-A World Review. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Design and Environmental Control of Tropical and Subtropical Greenhouses 578, Taichung, Taiwan, 15–18 April 2001; pp. 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomelli, G.; Furfaro, R.; Kacira, M.; Patterson, L.; Story, D.; Boscheri, G.; Lobascio, C.; Sadler, P.; Pirolli, M.; Remiddi, R.; et al. Bio-regenerative life support system development for Lunar/Mars habitats. In Proceedings of the 42nd International Conference on Environmental Systems, San Diego, CA, USA, 15–19 July 2012; p. 3463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, P.D.; Furfaro, R.; Patterson, R.L. Prototype BLSS lunar-Mars habitat design. In Proceedings of the 44th International Conference on Environmental Systems, Tuscon, AZ, USA, 13–17 July 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Stamford, J.D.; Stevens, J.; Mullineaux, P.M.; Lawson, T. LED lighting: A grower’s guide to light spectra. HortScience 2023, 58, 180–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paponov, I.A.; Paponov, M. Supplemental lighting in controlled environment agriculture: Enhancing photosynthesis, growth, and sink activity. CABI Rev. 2025, 20, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurga, A.; Pacak, A.; Pandelidis, D.; Kaźmierczak, B. Condensate as a water source in terrestrial and extra-terrestrial conditions. Water Resour. Ind. 2023, 29, 100196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreschel, T.W.; Brown, C.S.; Piastuch, W.C.; Hinkle, C.R.; Sager, J.C.; Wheeler, R.M.; Knott, W.M. A Summary of Porous Tube Plant Nutrient Delivery System Investigations from 1985 to 1991; NASA Technical Memorandum; The National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Kennedy Space Center: Cocoa Beach, FL, USA, 1992; p. 107546. [Google Scholar]

- Shamshiri, R.R.; Kalantari, F.; Ting, K.C.; Thorp, K.R.; Hameed, I.A.; Weltzien, C.; Ahmad, D.; Shad, Z.M. Advances in greenhouse automation and controlled environment agriculture: A transition to plant factories and urban agriculture. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2018, 11, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mungin, R.; Weislogel, M.M.; Hatch, T.R.; McQuillen, J.B. Omni-gravity hydroponics for space exploration. In Proceedings of the 49th International Conference on Environmental Systems, Boston, MA, USA, 7–11 July 2019. no. GRC-E-DAA-TN66314. [Google Scholar]

- Hangarter, R.P. Gravity, light and plant form. Plant. Cell Environ. 1997, 20, 796–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baluška, F.; Volkmann, D. Mechanical aspects of gravity-controlled growth, development and morphogenesis. In Mechanical Integration of Plant Cells and Plants; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 195–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasenstein, K.H.; Van Loon, J.; Beysens, D. Clinostats and other rotating systems—Design, function, and limitations. In Generation and Applications of Extra-Terrestrial Environments on Earth; River Publishers: Roma, Italy, 2015; Volume 14, pp. 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzi, G.; Perbal, G. Actin filaments responsible for the location of the nucleus in the lentil statocyte are sensitive to gravity. Biol. Cell 1990, 68, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hostetler, A.N.; Kennebeck, E.; Reneau, J.W.; Caldwell, D.L.; Iyer-Pascuzzi, A.S.; Sparks, E.E. Vascular anatomy changes in tomato stems grown under simulated microgravity. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.H.; Dahl, A.O.; Chapman, D.K. Morphology of Arabidopsis grown under chronic centrifugation and on the clinostat. Plant Physiol. 1976, 57, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.H. Centrifuges: Evolution of their uses in plant gravitational biology and new directions for research on the ground and in spaceflight. ASGSB Bull. 1992, 5, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Durante, M.; Cucinotta, F.A. Cosmic rays: Hurdles on the road to mars. Nucl. Phys. News 2014, 24, 32–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llamas, H.J.; Aplin, K.L.; Berthoud, L. Effectiveness of Martian regolith as a radiation shield. Planet. Space Sci. 2022, 218, 105517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaba, T.C.; Mertens, C.J.; Blattnig, S.R. Radiation Shielding Optimization on Mars; NASA/TP–2013-217983; NASA Langley Research Center: Hampton, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, T.T.; El-Genk, M.S. Dose estimates in a lunar shelter with regolith shielding. Acta Astronaut. 2009, 64, 697–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, L.; Adams, J.; Blattnig, S.; Clowdsley, M.; Fry, D.; Jun, I.; McLeod, C.; Minow, J.; Moore, D.; Norbury, J.; et al. Solar particle event storm shelter requirements for missions beyond low Earth orbit. Life Sci. Space Res. 2018, 17, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfandabadi, M.M.; Bannova, O. Pressurized Greenhouse: A Responsive Environment to Partial Gravity Conditions. In Proceedings of the Earth and Space 2021: Space Exploration, Utilization, Engineering, and Construction in Extreme Environments—Selected Papers from the 17th Biennial International Conference on Engineering, Science, Construction, and Operations in Challenging Environments, Virtual, 19–23 April 2021; pp. 832–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rygalov, V.Y.; Bucklin, R.A.; Drysdale, A.E.; Fowler, P.A.; Wheeler, R.M. Low Pressure Greenhouse Concepts for Mars: Atmospheric Composition; SAE Technical Paper; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corey, K.A.; Wheeler, R.M. Gas exchange in NASA’s biomass production chamber. Bioscience 1992, 42, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udert, K.M.; Buckley, C.A.; Wächter, M.; McArdell, C.S.; Kohn, T.; Strande, L.; Zöllig, H.; Fumasoli, A.; Oberson, A.; Etter, B. Technologies for the treatment of source-separated urine in the eThekwini Municipality. Water SA 2015, 41, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppens, J.; Lindeboom, R.; Muys, M.; Coessens, W.; Alloul, A.; Meerbergen, K.; Lievens, B.; Clauwaert, P.; Boon, N.; Vlaeminck, S.E. Nitrification and microalgae cultivation for two-stage biological nutrient valorization from source separated urine. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 211, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Güiza, M.S.; Mata-Alvarez, J.; Rivera, J.M.C.; Garcia, S.A. Nutrient recovery technologies for anaerobic digestion systems: An overview. Rev. Ion 2016, 29, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Løes, A.-K. Feeding the reactors: Potentials in re-cycled organic fertilisers. Org. Agric. 2021, 11, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]