Pros and Cons of Interactions Between Crops and Beneficial Microbes

Abstract

1. Introduction

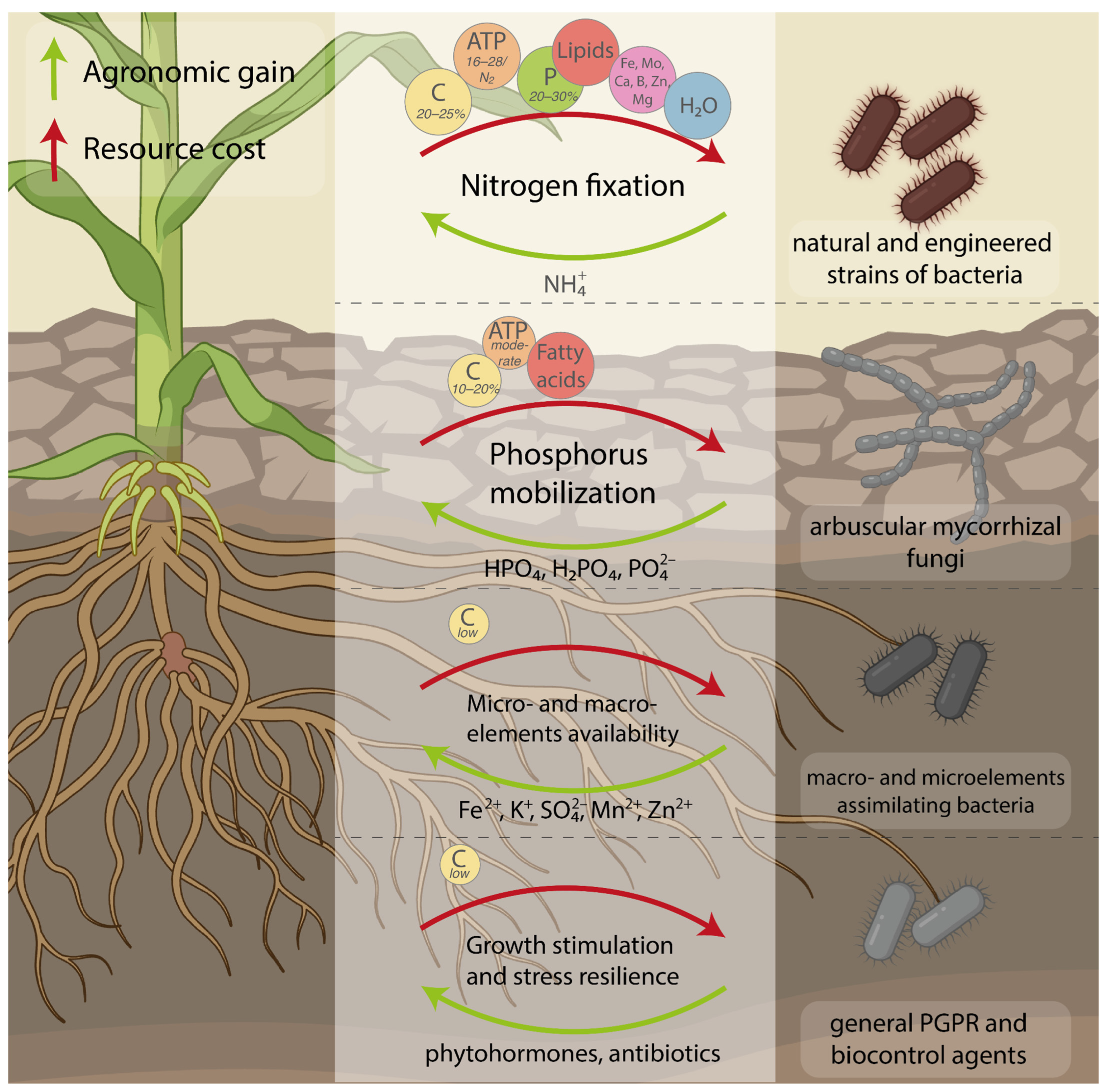

2. Nitrogen Fixation

2.1. Natural Strains of Nitrogen-Fixing Bacteria

| Nitrogen-Fixating Microbe | Estimated Yield Increase | Crop | Conditions | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rhizobium | ~10–40% | Legumes | Compared to farmers’ local practices | [18,19,20,21] |

| Azospirillum | ~5–15% | Cereals | Compared to untreated control | [25,26,27,28] |

| Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus | ~5–15% | Vegetables | Compared to untreated control and to 100% N and P treatment | [29,30,31] |

| Methylobacterium symbioticum | ~20–30% | Non-legumes | In nitrogen deficiency | [32] |

2.2. Engineered Nitrogen-Fixing Bacteria

2.3. How Expensive Are Nitrogen-Fixing Microbes for Plants?

| Microbial Partnership | Carbon Cost (% of Photosynthate) | ATP/Reducing Power | Macronutrients Invested | Micronutrients Invested | Water/Ion Fluxes | Specific Symbiotic Tissue/Organ Development | Signaling and Immune Modulation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen Fixation (rhizobial symbiosis or N2-fixing PGPR) | High: ~20–25% of plant photosynthate [63] | High: N2 fixation is energy-intensive—~16–28 ATP per N2 reduced [64] | Phosphorus—~20–30% [65]; Mg—required for bacterial nitrogenase, regulators of symbiotic efficiency [69,70] Lipids—substantial new membrane synthesis; some plant S and N invested in nodule proteins and enzymes [66] | Fe and Mo—required for bacterial nitrogenase [64]; B—essential for infection thread formation and nodule development. Ca—a second messenger in Nod factor signaling [67] Zn—regulate transcriptional factor Fixation Under Nitrate [68] | Moderate: Nodules require water and nutrients from the host [71] | Yes: Formation of root nodules [66] | Extensive signaling: plant roots secrete flavonoids to attract compatible rhizobia, bacteria produce Nod factors that trigger host signaling. The host actively suppresses immunity in infected root zones to accommodate rhizobia without mounting defense responses [64] |

| Phosphorus Mobilization (arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi) | Moderate: ~10–20% of photosynthate allocated to AM fungi [72] | Moderate: Some host ATP investment for symbiosis maintenance and active transport of nutrients [73] | Lipids: Host plant supplies fatty acids to AM fungus in addition to sugars [74,75] | Minimal | Low/beneficial: AM fungi improve the host’s water and mineral uptake, often enhancing drought tolerance [76] | Partial: No new organ, but arbuscules form inside root cortical cells as specialized exchange sites [77] | Signaling: Plant roots exude strigolactones that stimulate AM fungal spore germination and hyphal branching [78]. Immune modulation: The plant initially detects AM fungi, but this is quickly downregulated. The host suppresses strong immunity to allow fungal entry, achieving a balanced symbiosis [79] |

| Potassium Solubilization (K-releasing microbes) | Low: reliant on root exudates [80] | Minimal: No significant ATP cost to the plant [81] | Negligible | Nonspecific | None beyond normal | None | Little active signaling Immune response is not strongly invoked |

| General PGPR (nutrient uptake enhancers, phytohormone producers, etc.) | Low: <10% carbon investment via root exudates [80] | Minimal: No direct ATP expense dedicated to the microbe. | Minor leaks as cues/nutrients: Plant roots exude amino acids, sugars, and organic acids that inadvertently feed PGPR [82] | Nonspecial | No extra demand: PGPR help the plant use water more efficiently under stress | No new organ | Signaling: Plants do not typically have a dedicated invite signal for general PGPR, but overall root exudate composition can shape microbial communities. Immune modulation: PGPR can prime the plant’s immunity—inducing Induced Systemic Resistance (ISR) that fortifies the plant against pathogens [82] |

| Biocontrol Agents (microbial antagonists against pests and pathogens) | Minimal: beneficial microbes feed on plant exudates or target pathogens [80] | None | None | None | No direct cost: these agents improve plant health and thereby can indirectly improve the plant’s water/nutrient uptake efficiency | None | Signaling: Plants under attack can call for help by releasing specific exudates to recruit biocontrol allies. Immune modulation: can trigger ISR. The plant must integrate signals from the biocontrol agent which primes the immune system without causing disease |

3. Phosphate Mobilization

3.1. Phosphate-Mobilizing Microbes

3.2. What Is the Metabolic Cost to Plants of Phosphorus Mobilization?

4. Assimilation of Other Micro- and Macronutrients

4.1. Microbial-Associated Absorption of K, Fe, and S

4.2. How Costly Is Potassium Solubilization for Plants?

5. Plant Growth Stimulation and Stress Resistance

5.1. Plant-Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria and Biocontrol Organisms

5.2. The Costs of PGPR and Biocontrol Micro-Organisms for Plants

6. The Downside of Plant-Microbial Symbiosis

6.1. Negative Effects of Plant-Microbe Interactions

6.2. Limitations of Plant Growth-Promoting Microbes on Crop Productivity in the Field

7. Emerging Strategies for Optimizing Plant–Microbe Symbioses

7.1. Cell-Type-Specific Genome Editing

7.2. Metabolic Rerouting and Enhanced Nutrient Exchange

8. Cost and Benefit of Commercial Microbial Inoculants

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATP | Adenosine Triphosphate |

| AM | Arbuscular Mycorrhiza |

| GM | Genetically Modified |

| ISR | Induced Systemic Resistance |

| MAMP | Microbe-Associated Molecular Pattern |

| NAD(P)H | Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide (Phosphate), reduced form |

| PGPR | Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria |

References

- Ashitha, A.; Rakhimol, K.R.; Mathew, J. Fate of the Conventional Fertilizers in Environment. In Controlled Release Fertilizers for Sustainable Agriculture; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 25–39. ISBN 9780128195550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penuelas, J.; Coello, F.; Sardans, J. A Better Use of Fertilizers Is Needed for Global Food Security and Environmental Sustainability. Agric. Food Secur. 2023, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puginier, C.; Keller, J.; Delaux, P.-M. Plant-Microbe Interactions That Have Impacted Plant Terrestrializations. Plant Physiol. 2022, 190, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timofeeva, A.M.; Galyamova, M.R.; Sedykh, S.E. Plant Growth-Promoting Soil Bacteria: Nitrogen Fixation, Phosphate Solubilization, Siderophore Production, and Other Biological Activities. Plants 2023, 12, 4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woźniak, M.; Siebielec, S. Agriculturally Important Groups of Microorganisms–Microbial Enhancement of Nutrient Availability. Curr. Agron. 2025, 54, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharina, B.B.U.; Raj, N.; Baker, S.; Mathew, J. Importance and Application of Nitrogen Fixing Bacteria. Ph.D. Thesis, Karnataka State Open University, Mysore, India, 6 June 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Wei, Q.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, D.; Chen, S.; Qian, W.; He, M.; Chen, P.; Zhou, X.; et al. Nitrogen Losses from Soil as Affected by Water and Fertilizer Management under Drip Irrigation: Development, Hotspots and Future Perspectives. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 296, 108791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, E. Contribution, Utilization, and Improvement of Legumes-Driven Biological Nitrogen Fixation in Agricultural Systems. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 767998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jach, M.E.; Sajnaga, E.; Ziaja, M. Utilization of Legume-Nodule Bacterial Symbiosis in Phytoremediation of Heavy Metal-Contaminated Soils. Biology 2022, 11, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seshadri, R.; Reeve, W.G.; Ardley, J.K.; Tennessen, K.; Woyke, T.; Kyrpides, N.C.; Ivanova, N.N. Discovery of Novel Plant Interaction Determinants from the Genomes of 163 Root Nodule Bacteria. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 16825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wekesa, C.; Jalloh, A.A.; Muoma, J.O.; Korir, H.; Omenge, K.M.; Maingi, J.M.; Furch, A.C.U.; Oelmüller, R. Distribution, Characterization and the Commercialization of Elite Rhizobia Strains in Africa. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, E. Competency of Rhizobial Inoculation in Sustainable Agricultural Production and Biocontrol of Plant Diseases. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 728014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahran, H.H. Rhizobium-Legume Symbiosis and Nitrogen Fixation under Severe Conditions and in an Arid Climate. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1999, 63, 968–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simms, E.L.; Taylor, D.L. Partner Choice in Nitrogen-Fixation Mutualisms of Legumes and Rhizobia. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2002, 42, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stępkowski, T.; Banasiewicz, J.; Granada, C.E.; Andrews, M.; Passaglia, L.M.P. Phylogeny and Phylogeography of Rhizobial Symbionts Nodulating Legumes of the Tribe Genisteae. Genes 2018, 9, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hnini, M.; Aurag, J. Prevalence, Diversity and Applications Potential of Nodules Endophytic Bacteria: A Systematic Review. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1386742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etesami, H. Root Nodules of Legumes: A Suitable Ecological Niche for Isolating Non-Rhizobial Bacteria with Biotechnological Potential in Agriculture. Curr. Res. Biotechnol. 2022, 4, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razafintsalama, H.; Trap, J.; Rabary, B.; Razakatiana, A.T.E.; Ramanankierana, H.; Rabeharisoa, L.; Becquer, T. Effect of Rhizobium Inoculation on Growth of Common Bean in Low-Fertility Tropical Soil Amended with Phosphorus and Lime. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, I.; Sarim, K.M.; Sikka, V.K.; Dudeja, S.S.; Gahlot, D.K. Developed Rhizobium Strains Enhance Soil Fertility and Yield of Legume Crops in Haryana, India. J. Basic Microbiol. 2024, 64, e2400327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zerihun, G.; Girma, A.; Sheleme, B. Rhizobium Inoculation and Sulphur Fertilizer Improved Yield, Nutrients Uptake and Protein Quality of Soybean (Glysine max L.) Varieties on Nitisols of Assosa Area, Western Ethiopia. Afr. J. Plant Sci. 2017, 11, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sufar, E.K.; Hasanaliyeva, G.; Wang, J.; Bilsborrow, P.; Rempelos, L.; Volakakis, N.; Baranski, M.; Leifert, C. Effect of Rhizobium Seed Inoculation on Grain Legume Yield and Protein Content—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Agric. Sci. Agron. 2024, 9, 2275410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mmbaga, G.W.; Mtei, K.; Ndakidemi, P.A. Yield and Fiscal Benefits of Rhizobium Inoculation Supplemented with Phosphorus (P) and Potassium (K) in Climbing Beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Grown in Northern Tanzania. Agric. Sci. 2015, 6, 783–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buernor, A.B.; Kabiru, M.R.; Bechtaoui, N.; Jibrin, J.M.; Asante, M.; Bouraqqadi, A.; Dahhani, S.; Ouhdouch, Y.; Hafidi, M.; Jemo, M. Grain Legume Yield Responses to Rhizobia Inoculants and Phosphorus Supplementation under Ghana Soils: A Meta-Synthesis. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 877433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pudasaini, R.; Raizada, M.N. Nodule Crushing: A Novel Technique to Decentralize Rhizobia Inoculant Technology and Empower Small-Scale Farmers to Enhance Legume Production and Income. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1423997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelagio-Flores, R.; Ravelo-Ortega, G.; García-Pineda, E.; López-Bucio, J. A Century of Azospirillum: Plant Growth Promotion and Agricultural Promise. Plant Signal. Behav. 2025, 20, 2551609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassán, F.; Coniglio, A.; López, G.; Molina, R.; Nievas, S.; de Carlan, C.L.N.; Donadio, F.; Torres, D.; Rosas, S.; Pedrosa, F.O.; et al. Everything You Must Know about Azospirillum and Its Impact on Agriculture and beyond. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2020, 56, 461–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veresoglou, S.D.; Menexes, G. Impact of Inoculation with Azospirillum Spp. on Growth Properties and Seed Yield of Wheat: A Meta-Analysis of Studies in the ISI Web of Science from 1981 to 2008. Plant Soil 2010, 337, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, J.Z.; de Almeida Roberto, L.; Hungria, M.; Corrêa, R.S.; Magri, E.; Correia, T.D. Meta-Analysis of Maize Responses to Azospirillum brasilense Inoculation in Brazil: Benefits and Lessons to Improve Inoculation Efficiency. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2022, 170, 104276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceballos-Aguirre, N.; Cuellar, J.A.; Restrepo, G.M.; Sánchez, Ó.J. Effect of the Application of Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus and Its Interaction with Nitrogen and Phosphorus Fertilization on Carrot Yield in the Field. Int. J. Agron. 2023, 2023, 6899532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceballos-Aguirre, N.; Restrepo, G.M.; Patiño, S.; Cuéllar, J.A.; Sánchez, Ó.J. Utilization of Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus in Tomato Crop: Interaction with Nitrogen and Phosphorus Fertilization. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallucchini, M. An Investigation into the Mechanisms Underlying the Plant Growth Promoting Properties of G. diazotrophicus. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Torres Vera, R.; Bernabé García, A.J.; Carmona Álvarez, F.J.; Martínez Ruiz, J.; Fernández Martín, F. Application and Effectiveness of Methylobacterium symbioticum as a Biological Inoculant in Maize and Strawberry Crops. Folia Microbiol. 2024, 69, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo, F.S.; Teixeira Filho, M.C.M.; Buzetti, S.; Pagliari, P.H.; Santini, J.M.K.; Alves, C.J.; Megda, M.M.; Nogueira, T.A.R.; Andreotti, M.; Arf, O. Maize Yield Response to Nitrogen Rates and Sources Associated with Azospirillum brasilense. Agron. J. 2019, 111, 1985–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, T.L.G.; Rosman, A.C.; Grativol, C.; de M Nogueira, E.; Baldani, J.I.; Hemerly, A.S. Sugarcane Genotypes with Contrasting Biological Nitrogen Fixation Efficiencies Differentially Modulate Nitrogen Metabolism, Auxin Signaling, and Microorganism Perception Pathways. Plants 2022, 11, 1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhold-Hurek, B.; Hurek, T. Life in Grasses: Diazotrophic Endophytes. Trends Microbiol. 1998, 6, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, M.M. Relationships between Nitrogen Fixation and Auxins Production in Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus Strains from Different Crops. Colomb. J. Biotechnol. 2009, 11, 84–93. [Google Scholar]

- Madhaiyan, M.; Poonguzhali, S.; Senthilkumar, M.; Lee, J.-S.; Lee, K.-C. Methylobacterium gossipiicola Sp. Nov., a Pink-Pigmented, Facultatively Methylotrophic Bacterium Isolated from the Cotton Phyllosphere. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2012, 62, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sy, A.; Giraud, E.; Jourand, P.; Garcia, N.; Willems, A.; de Lajudie, P.; Prin, Y.; Neyra, M.; Gillis, M.; Boivin-Masson, C.; et al. Methylotrophic Methylobacterium Bacteria Nodulate and Fix Nitrogen in Symbiosis with Legumes. J. Bacteriol. 2001, 183, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreote, F.D.; Lacava, P.T.; Gai, C.S.; Araújo, W.L.; Maccheroni, W., Jr.; van Overbeek, L.S.; van Elsas, J.D.; Azevedo, J.L. Model Plants for Studying the Interaction between Methylobacterium mesophilicum and Xylella fastidiosa. Can. J. Microbiol. 2006, 52, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.corteva.co.uk/content/dam/dpagco/corteva/eu/gb/en/files/UtrishaN-tech-sheet-Cereals.pdf#:~:text=How (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Available online: https://symborg.com/us/news-us/first-usda-verification-for-biostimulant/#:~:text=Corteva%20Agriscience%20Receives%20First%20USDA,PVP (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Giller, K.E.; James, E.K.; Ardley, J.; Unkovich, M.J. Science Losing Its Way: Examples from the Realm of Microbial N2-Fixation in Cereals and Other Non-Legumes. Plant Soil 2024, 511, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naiman, A.D.; Latrónico, A.; García de Salamone, I.E. Inoculation of Wheat with Azospirillum brasilense and Pseudomonas fluorescens: Impact on the Production and Culturable Rhizosphere Microflora. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2009, 45, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aasfar, A.; Meftah Kadmiri, I.; Azaroual, S.E.; Lemriss, S.; Mernissi, N.E.; Bargaz, A.; Zeroual, Y.; Hilali, A. Agronomic Advantage of Bacterial Biological Nitrogen Fixation on Wheat Plant Growth under Contrasting Nitrogen and Phosphorus Regimes. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1388775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novello, G.; Bona, E.; Nasuelli, M.; Massa, N.; Sudiro, C.; Campana, D.C.; Gorrasi, S.; Hochart, M.L.; Altissimo, A.; Vuolo, F.; et al. The Impact of Nitrogen-Fixing Bacteria-Based Biostimulant Alone or in Combination with Commercial Inoculum on Tomato Native Rhizosphere Microbiota and Production: An Open-Field Trial. Biology 2024, 13, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.wusf.org/environment/2023-06-11/the-price-of-plenty-technology-help-find-better-fertilizer (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Kaur, T.; Devi, R.; Kumar, S.; Sheikh, I.; Kour, D.; Yadav, A.N. Microbial Consortium with Nitrogen Fixing and Mineral Solubilizing Attributes for Growth of Barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Heliyon 2022, 8, e09326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, P.S.O.; Lacerda-Junior, G.V.; Mascarin, G.M.; Guimarães, R.A.; Medeiros, F.H.V.; Arthurs, S.; Bettiol, W. Microbial Consortia of Biological Products: Do They Have a Future? Biol. Control 2024, 188, 105439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geerdes, N.; de Lorimier, P.; Howe, A.; Shade, A. Synthetic Microbial Communities: Bridging Research and Application in Second-Generation Bioenergy Feedstock Microbiomes. Plant Soil 2025, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, T.; Liu, Q.; Chen, M.; Tang, S.; Ou, L.; Li, D. Synthetic Microbial Communities Enhance Pepper Growth and Root Morphology by Regulating Rhizosphere Microbial Communities. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, G.; Han, Z.; Wang, X.; Malacrinò, A.; Kang, T.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, H. Synthetic Microbial Communities Rescues Strawberry from Soil-Borne Disease by Enhancing Soil Functional Microbial Abundance and Multifunctionality. J. Adv. Res. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, M.; Durán-Wendt, D.; Garrido-Sanz, D.; Carrera-Ruiz, L.; Vázquez-Arias, D.; Redondo-Nieto, M.; Martín, M.; Rivilla, R. Functional Characterization of a Synthetic Bacterial Community (SynCom) and Its Impact on Gene Expression and Growth Promotion in Tomato. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayanthan, A.; Ordoñez, P.A.C.; Oresnik, I.J. The Role of Synthetic Microbial Communities (SynCom) in Sustainable Agriculture. Front. Agron. 2022, 4, 896307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankievicz, V.C.S.; Irving, T.B.; Maia, L.G.S.; Ané, J.-M. Are We There yet? The Long Walk towards the Development of Efficient Symbiotic Associations between Nitrogen-Fixing Bacteria and Non-Leguminous Crops. BMC Biol. 2019, 17, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.boe.es/doue/2019/170/L00001-00114.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Santos, F.; Melkani, S.; Oliveira-Paiva, C.; Bini, D.; Pavuluri, K.; Gatiboni, L.; Mahmud, A.; Torres, M.; McLamore, E.; Bhadha, J.H. Biofertilizer Use in the United States: Definition, Regulation, and Prospects. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 108, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindasamy, R.; Gayathiri, E.; Sankar, S.; Venkidasamy, B.; Prakash, P.; Rekha, K.; Savaner, V.; Pari, A.; Thirumalaivasan, N.; Thiruvengadam, M. Emerging Trends of Nanotechnology and Genetic Engineering in Cyanobacteria to Optimize Production for Future Applications. Life 2022, 12, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temme, K.; Shah, N.; Eskiyenenturk, B.O.; Bloch, S.; Tamsir, A. Modified Bacterial Strains for Improved Fixation of Nitrogen. U.S. Patent Application No. 17/922,712, 17 August 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://www.pivotbio.com/press-releases/peer-reviewed-study-validates-pivot-bios-gene-edited-microbes-as-a-third-source-of-nitrogen-delivery#:~:text=Harnessing%20proprietary%20gene,in%20their%20nitrogen%20management%20programs (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Woodward, L.P.; Sible, C.N.; Seebauer, J.R.; Below, F.E. Soil Inoculation with Nitrogen-fixing Bacteria to Supplement Maize Fertilizer Need. Agron. J. 2025, 117, e21729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, M.-H.; Zhang, J.; Toth, T.; Khokhani, D.; Geddes, B.A.; Mus, F.; Garcia-Costas, A.; Peters, J.W.; Poole, P.S.; Ané, J.-M.; et al. Control of Nitrogen Fixation in Bacteria That Associate with Cereals. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 314–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blois, M. Can Microbes Replace Synthetic Fertilizer? Chem. Eng. News 2023, 101, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Chen, R. Nitrogen and Phosphorus Signaling and Transport During Legume–Rhizobium Symbiosis. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 683601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soumare, A.; Diedhiou, A.G.; Thuita, M.; Hafidi, M.; Ouhdouch, Y.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; Kouisni, L. Exploiting Biological Nitrogen Fixation: A Route Towards a Sustainable Agriculture. Plants 2020, 9, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isidra-Arellano, M.C.; Valdés-López, O. Understanding the Crucial Role of Phosphate and Iron Availability in Regulating Root Nodule Symbiosis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2024, 65, 1925–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brear, E.M.; Day, D.A.; Smith, P.M.C. Iron: An Essential Micronutrient for the Legume-Rhizobium Symbiosis. Front. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 56807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolanos, L.; Brewin, N.J.; Bonilla, I. Effects of Boron on Rhizobium-Legume Cell-Surface Interactions and Nodule Development. Plant Physiol. 1996, 110, 1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Bjørk, P.K.; Kolte, M.V.; Poulsen, E.; Dedic, E.; Drace, T.; Andersen, S.U.; Nadzieja, M.; Liu, H.; Castillo-Michel, H.; et al. Zinc Mediates Control of Nitrogen Fixation via Transcription Factor Filamentation. Nature 2024, 631, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seefeldt, L.C.; Hoffman, B.M.; Dean, D.R. Mechanism of Mo-Dependent Nitrogenase. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009, 78, 701–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.-R.; Peng, W.-T.; Nie, M.-M.; Bai, S.; Chen, C.-Q.; Liu, Q.; Guo, Z.-L.; Liao, H.; Chen, Z.-C. Carbon-Nitrogen Trading in Symbiotic Nodules Depends on Magnesium Import. Curr. Biol. 2022, 32, 4337–4349.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachiya, T.; Sakakibara, H. Interactions between Nitrate and Ammonium in Their Uptake, Allocation, Assimilation, and Signaling in Plants. EXBOTJ 2016, 68, erw449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, A.E.; Groten, K. The Costs and Benefits of Plant-Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungal Interactions. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2022, 73, 649–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del-Saz, N.F.; Romero-Munar, A.; Alonso, D.; Aroca, R.; Baraza, E.; Flexas, J.; Ribas-Carbo, M. Respiratory ATP Cost and Benefit of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Symbiosis with Nicotiana tabacum at Different Growth Stages and under Salinity. J. Plant Physiol. 2017, 218, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keymer, A.; Pimprikar, P.; Wewer, V.; Huber, C.; Brands, M.; Bucerius, S.L.; Delaux, P.-M.; Klingl, V.; von Röpenack-Lahaye, E.; Wang, T.L.; et al. Lipid Transfer from Plants to Arbuscular Mycorrhiza Fungi. Elife 2017, 6, e29107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luginbuehl, L.H.; Menard, G.N.; Kurup, S.; Van Erp, H.; Radhakrishnan, G.V.; Breakspear, A.; Oldroyd, G.E.D.; Eastmond, P.J. Fatty Acids in Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Are Synthesized by the Host Plant. Science 2017, 356, 1175–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://extension.okstate.edu/fact-sheets/mycorrhizal-fungi.html (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Luginbuehl, L.H.; Oldroyd, G.E.D. Understanding the Arbuscule at the Heart of Endomycorrhizal Symbioses in Plants. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, R952–R963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besserer, A.; Puech-Pagès, V.; Kiefer, P.; Gomez-Roldan, V.; Jauneau, A.; Roy, S.; Portais, J.C.; Roux, C.; Bécard, G.; Séjalon-Delmas, N. Strigolactones Stimulate Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi by Activating Mitochondria. PLoS Biol. 2006, 4, e226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Xie, W.; Chen, B. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Symbiosis Affects Plant Immunity to Viral Infection and Accumulation. Viruses 2019, 11, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargallo-Garriga, A.; Preece, C.; Sardans, J.; Oravec, M.; Urban, O.; Peñuelas, J. Root Exudate Metabolomes Change under Drought and Show Limited Capacity for Recovery. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maierhofer, T.; Scherzer, S.; Carpaneto, A.; Müller, T.D.; Pardo, J.M.; Hänelt, I.; Geiger, D.; Hedrich, R. Arabidopsis HAK5 under Low K+ Availability Operates as PMF Powered High-Affinity K+ Transporter. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacheron, J.; Desbrosses, G.; Bouffaud, M.-L.; Touraine, B.; Moënne-Loccoz, Y.; Muller, D.; Legendre, L.; Wisniewski-Dyé, F.; Prigent-Combaret, C. Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria and Root System Functioning. Front. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 57135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidaj, D.; Krysa, M.; Susniak, K.; Matys, J.; Komaniecka, I.; Sroka-Bartnicka, A. Biological Activity of Nod Factors. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2020, 67, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.B.; Sayyed, R.Z.; Trivedi, M.H.; Gobi, T.A. Phosphate Solubilizing Microbes: Sustainable Approach for Managing Phosphorus Deficiency in Agricultural Soils. Springerplus 2013, 2, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos Cabrera, E.V.; Delgado Espinosa, Z.Y.; Solis Pino, A.F. Use of Phosphorus-Solubilizing Microorganisms as a Biotechnological Alternative: A Review. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Cai, B. Phosphate-Solubilizing Bacteria: Advances in Their Physiology, Molecular Mechanisms and Microbial Community Effects. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figiel, S.; Rusek, P.; Ryszko, U.; Brodowska, M.S. Microbially Enhanced Biofertilizers: Technologies, Mechanisms of Action, and Agricultural Applications. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfante, P.; Genre, A. Mechanisms Underlying Beneficial Plant-Fungus Interactions in Mycorrhizal Symbiosis. Nat. Commun. 2010, 1, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfante, P.; Genre, A. Plants and Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi: An Evolutionary-Developmental Perspective. Trends Plant Sci. 2008, 13, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, H.-J.; Cargill, R.I.M.; Van Nuland, M.E.; Hagen, S.C.; Field, K.J.; Sheldrake, M.; Soudzilovskaia, N.A.; Kiers, E.T. Mycorrhizal Mycelium as a Global Carbon Pool. Curr. Biol. 2023, 33, R560–R573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://ag.fmc.com/ca/en/biologicals/jumpstart#:~:text=JumpStart%C2%AE%20,plant%20roots%2C%20releasing%20phosphate (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Available online: https://www.grainews.ca/news/if-you-plan-to-cut-back-on-phosphorus-fertilizer-this-year-you-could-try-jumpstart-to-see-if-it-helps-bridge-the-gap/ (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Available online: https://www.crop.bayer.com.au/-/media/bcs-inter/ws_australia/use-our-products/product-resources/tagteam/tagteam-product-guide.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Leggett, M.; Newlands, N.K.; Greenshields, D.; West, L.; Inman, S.; Koivunen, M.E. Maize Yield Response to a Phosphorus-Solubilizing Microbial Inoculant in Field Trials. J. Agric. Sci. 2015, 153, 1464–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, P.; Zhou, B.; Bi, Y.; Chen, X.; Yao, S. Study on the Microbial Mechanism of Bacillus subtilis in Improving Drought Tolerance and Cotton Yield in Arid Areas. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogugua, U.V.; Ogbuewu, I.P.; Mbajiorgu, C.A.; Adriaanse, P. Meta-Analysis of Biofertilizer Effects of Bacillus Species on Tomato Yield. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 34007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://agris.fao.org/search/en/providers/122419/records/6474a98a1a9cd02c1d8fdd63 (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Available online: https://revistacultivar.com/news/biomaphos-yielded-R105-million-to-the-country-in-2020-with-increased-soybean-and-corn-productivity (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Zhang, S.; Lehmann, A.; Zheng, W.; You, Z.; Rillig, M.C. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Increase Grain Yields: A Meta-Analysis. New Phytol. 2019, 222, 543–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Shi, Z.; Chen, X.; Gao, J.; Wang, X. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Increase Crop Yields by Improving Biomass under Rainfed Condition: A Meta-Analysis. PeerJ 2022, 10, e12861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijri, M. Analysis of a Large Dataset of Mycorrhiza Inoculation Field Trials on Potato Shows Highly Significant Increases in Yield. Mycorrhiza 2016, 26, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Affokpon, A.; Coyne, D.L.; Lawouin, L.; Tossou, C.; Dossou Agbèdè, R.; Coosemans, J. Effectiveness of Native West African Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi in Protecting Vegetable Crops against Root-Knot Nematodes. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2011, 47, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Barragán, A. The Use of Arbuscular Mycorrhizae to Control Onion White Rot (Sclerotium Cepivorum Berk.) under Field Conditions. Mycorrhiza 1996, 6, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.iffco.in/en/phosphate-solubalizing-bacteria#:~:text=Phosphorous%20Solution%20Bio%20Fertiliser%20contains,need%20for%20synthetic%20phosphate%20fertilizers (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Gao, X.; Guo, H.; Zhang, Q.; Guo, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, C.; Gou, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wei, J.; Chen, A.; et al. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi (AMF) Enhanced the Growth, Yield, Fiber Quality and Phosphorus Regulation in Upland Cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.). Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Reis, G.A.; Martínez-Burgos, W.J.; Pozzan, R.; Pastrana Puche, Y.; Ocán-Torres, D.; de Queiroz Fonseca Mota, P.; Rodrigues, C.; Lima Serra, J.; Scapini, T.; Karp, S.G.; et al. Comprehensive Review of Microbial Inoculants: Agricultural Applications, Technology Trends in Patents, and Regulatory Frameworks. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhanja, E.; Das, R.; Begum, Y.; Mondal, S.K. Study of Pyrroloquinoline Quinine from Phosphate-Solubilizing Microbes Responsible for Plant Growth: In Silico Approach. Front. Agron. 2021, 3, 667339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulse, C.N.; Chovatia, M.; Agosto, C.; Wang, G.; Hamilton, M.; Deutsch, S.; Yoshikuni, Y.; Blow, M.J. Engineered Root Bacteria Release Plant-Available Phosphate from Phytate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 85, e01210-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Wang, W.; Xie, Q.; Liu, N.; Liu, L.; Wang, D.; Zhang, X.; Yang, C.; Chen, X.; Tang, D.; et al. Plants Transfer Lipids to Sustain Colonization by Mutualistic Mycorrhizal and Parasitic Fungi. Science 2017, 356, 1172–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, V.S.; Bahadur, I.; Maurya, B.R.; Kumar, A.; Meena, R.K.; Meena, S.K.; Verma, J.P. Potassium-Solubilizing Microorganism in Evergreen Agriculture: An Overview. In Potassium Solubilizing Microorganisms for Sustainable Agriculture; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2016; pp. 1–20. ISBN 9788132227748. [Google Scholar]

- Etesami, H.; Emami, S.; Alikhani, H.A. Potassium Solubilizing Bacteria (KSB): Mechanisms, Promotion of Plant Growth, and Future Prospects—A Review. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2017, 17, 897–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattar, A.; Naveed, M.; Ali, M.; Zahir, Z.A.; Nadeem, S.M.; Yaseen, M.; Meena, V.S.; Farooq, M.; Singh, R.; Rahman, M.; et al. Perspectives of Potassium Solubilizing Microbes in Sustainable Food Production System: A Review. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2019, 133, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, V.S.; Maurya, B.R.; Meena, S.K.; Meena, R.K.; Kumar, A.; Verma, J.P.; Singh, N.P. Can Bacillus Species Enhance Nutrient Availability in Agricultural Soils? In Bacilli and Agrobiotechnology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 367–395. ISBN 9783319444086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basak, B.B.; Biswas, D.R. Influence of Potassium Solubilizing Microorganism (Bacillus mucilaginosus) and Waste Mica on Potassium Uptake Dynamics by Sudan Grass (Sorghum vulgare Pers.) Grown under Two Alfisols. Plant Soil 2009, 317, 235–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odoh, C.K.; Sam, K.; Zabbey, N.; Eze, C.N.; Nwankwegu, A.S.; Laku, C.; Dumpe, B.B. Microbial Consortium as Biofertilizers for Crops Growing under the Extreme Habitats. In Sustainable Development and Biodiversity; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 381–424. ISBN 9783030384524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karuppiah, V.; Murugan, S.; Panneerselvam, S.; Thangavel, K. Microbial Siderophores as Molecular Shuttles for Metal Cations: Sources, Sinks and Application Perspectives. Arch. Microbiol. 2023, 205, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartik, V.P.; Chandwani, S.; Amaresan, N. Augmenting the Bioavailability of Iron in Rice Grains from Field Soils through the Application of Iron-Solubilizing Bacteria. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2023, 76, ovac038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarpong, C.K.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Q.; Wang, W.; Jamali, Z.H.; Yong, T.; Chang, X.; Yang, W.; Wang, Y.; Song, C. Improvement of Plant Microbiome Using Inoculants for Agricultural Production: A Sustainable Approach for Reducing Fertilizer Application. Can. J. Soil Sci. 2021, 101, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, S.; Sindhu, S.S.; Dhanker, R.; Kumari, A. Microbes-Mediated Sulphur Cycling in Soil: Impact on Soil Fertility, Crop Production and Environmental Sustainability. Microbiol. Res. 2023, 271, 127340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.msaforganics.com/bio-fertilizers-1/sulphur-solubilizing-bacteria?srsltid=AfmBOor6l8vd_3C7hKd7RoDVMKaPsv3n2j1aR2wP8I23oBpEE6VkBRyT (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Available online: https://www.indogulfbioag.com/sulphur-solubilizing-bacteria (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Available online: https://peptechbio.com/products/sulphur-solubilizing-bacteria-ssb-pep/ (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Ijaz, A.; Mumtaz, M.Z.; Wang, X.; Ahmad, M.; Saqib, M.; Maqbool, H.; Zaheer, A.; Wang, W.; Mustafa, A. Insights into Manganese Solubilizing bacillus Spp. For Improving Plant Growth and Manganese Uptake in Maize. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 719504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srithaworn, M.; Jaroenthanyakorn, J.; Tangjitjaroenkun, J.; Suriyachadkun, C.; Chunhachart, O. Zinc Solubilizing Bacteria and Their Potential as Bioinoculant for Growth Promotion of Green Soybean (Glycine max L. Merr.). PeerJ 2023, 11, e15128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assunção, A.G.L.; Cakmak, I.; Clemens, S.; González-Guerrero, M.; Nawrocki, A.; Thomine, S. Micronutrient Homeostasis in Plants for More Sustainable Agriculture and Healthier Human Nutrition. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 1789–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesenbauer, J.; Gorka, S.; Jenab, K.; Schuster, R.; Kumar, N.; Rottensteiner, C.; König, A.; Kraemer, S.; Inselsbacher, E.; Kaiser, C. Preferential Use of Organic Acids over Sugars by Soil Microbes in Simulated Root Exudation. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2025, 203, 109738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breedt, G.; Korsten, L.; Gokul, J.K. Enhancing Multi-Season Wheat Yield through Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria Using Consortium and Individual Isolate Applications. Folia Microbiol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Jian, Q.; Yao, X.; Guan, L.; Li, L.; Liu, F.; Zhang, C.; Li, D.; Tang, H.; Lu, L. Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) Improve the Growth and Quality of Several Crops. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ipek, M.; Pirlak, L.; Esitken, A.; Figen Dönmez, M.; Turan, M.; Sahin, F. Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (pgpr) Increase Yield, Growth and Nutrition of Strawberry under High-Calcareous Soil Conditions. J. Plant Nutr. 2014, 37, 990–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütz, L.; Gattinger, A.; Meier, M.; Müller, A.; Boller, T.; Mäder, P.; Mathimaran, N. Improving Crop Yield and Nutrient Use Efficiency via Biofertilization-A Global Meta-Analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Macdonald, C.A.; Singh, B.K. Application of Microbial Inoculants Significantly Enhances Crop Productivity: A Meta-analysis of Studies from 2010 to 2020. J. Sustain. Agric. Environ. 2022, 1, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick, B.R. Bacteria with ACC Deaminase Can Promote Plant Growth and Help to Feed the World. Microbiol. Res. 2014, 169, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandra, D.; Srivastava, R.; Gupta, V.V.S.R.; Franco, C.M.M.; Sharma, A.K. Evaluation of ACC-Deaminase-Producing Rhizobacteria to Alleviate Water-Stress Impacts in Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Plants. Can. J. Microbiol. 2019, 65, 387–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.P.; Vidal, M.S.; Baldani, J.I. Exploring ACC Deaminase-Producing Bacteria for Drought Stress Mitigation in Brachiaria. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1607697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish, S.; Zafar-ul-Hye, M.; Fahad, S.; Saud, S.; Brtnicky, M.; Hammerschmiedt, T.; Datta, R. Drought Stress Alleviation by ACC Deaminase Producing Achromobacter Xylosoxidans and Enterobacter Cloacae, with and without Timber Waste Biochar in Maize. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockwell, V.O.; Davis, E.W., 2nd; Carey, A.; Shaffer, B.T.; Mavrodi, D.V.; Hassan, K.A.; Hockett, K.; Thomashow, L.S.; Paulsen, I.T.; Loper, J.E. pA506, a Conjugative Plasmid of the Plant Epiphyte Pseudomonas Fluorescens A506. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 5272–5282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Zhang, M.; Du, L.; Zhang, L.; Li, B. Effects of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens QST713 on Photosynthesis and Antioxidant Characteristics of Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) under Drought Stress. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Johnson, K.B.; Mukhtar, S.; Nason, S.; Huntley, R.; Millet, F.; Yang, C.-H.; Hassani, M.A.; Zuverza-Mena, N.; Sundin, G.W. From the Fire Blight Biocontrol Product, Blossom Protect, Induces Host Resistance in Apple Flowers. Phytopathology 2023, 113, 1192–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.isaaa.org/kc/cropbiotechupdate/article/default.asp?ID=3416 (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Johnson, N.C.; Graham, J.-H.; Smith, F.A. Functioning of Mycorrhizal Associations along the Mutualism–parasitism Continuum. New Phytol. 1997, 135, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drew, G.C.; Stevens, E.J.; King, K.C. Microbial Evolution and Transitions along the Parasite-Mutualist Continuum. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 623–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, S.C.; Cleveland, C.C.; Townsend, A.R. Functional Ecology of Free-Living Nitrogen Fixation: A Contemporary Perspective. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2011, 42, 489–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, T.T.; Pin, U.L.; Ghazali, A.H.A. Influence of External Nitrogen on Nitrogenase Enzyme Activity and Auxin Production in Herbaspirillum Seropedicae (Z78). Trop. Life Sci. Res. 2015, 26, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Oldroyd, G.E.D.; Leyser, O. A Plant’s Diet, Surviving in a Variable Nutrient Environment. Science 2020, 368, eaba0196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menge, D.N.L.; Levin, S.A.; Hedin, L.O. Facultative versus Obligate Nitrogen Fixation Strategies and Their Ecosystem Consequences. Am. Nat. 2009, 174, 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- diCenzo, G.C.; Checcucci, A.; Bazzicalupo, M.; Mengoni, A.; Viti, C.; Dziewit, L.; Finan, T.M.; Galardini, M.; Fondi, M. Metabolic Modelling Reveals the Specialization of Secondary Replicons for Niche Adaptation in Sinorhizobium Meliloti. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek, K.; Bell, C.A. Exploited Mutualism: The Reciprocal Effects of Plant Parasitic Nematodes on the Mechanisms Underpinning Plant-Mutualist Interactions. New Phytol. 2025, 246, 2435–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, B.; Gaşpar, S.; Camen, D.; Ciobanu, I.; Sumălan, R. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi in Terms of Symbiosis-Parasitism Continuum. Commun. Agric. Appl. Biol. Sci. 2011, 76, 653–659. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Porter, S.S.; Sachs, J.L. Agriculture and the Disruption of Plant-Microbial Symbiosis. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2020, 35, 426–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.H.; Abbott, L.K. Wheat Responses to Aggressive and Non-Aggressive Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi. Plant Soil 2000, 220, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, E.J.; Cotsaftis, O.; Tester, M.; Smith, F.A.; Smith, S.E. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Inhibition of Growth in Barley Cannot Be Attributed to Extent of Colonization, Fungal Phosphorus Uptake or Effects on Expression of Plant Phosphate Transporter Genes. New Phytol. 2009, 181, 938–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Wang, Z.; Guo, M.; Qu, L.; Biere, A. Effects of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi on Plant Growth and Herbivore Infestation Depend on Availability of Soil Water and Nutrients. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1101932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Bao, X.; Li, S. Effects of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi on Rice Growth under Different Flooding and Shading Regimes. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 756752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, P.; Shi, Z.; Diao, F.; Hao, L.; Zhang, J.; Xu, J.; Wang, L.; Dang, Z.; Guo, W. Effects of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi on Growth and Na+ Accumulation of Suaeda Glauca (Bunge) Grown in Salinized Wetland Soils. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2021, 166, 104065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thielicke, M.; Ahlborn, J.; Eichler-Löbermann, B.; Eulenstein, F. On the Negative Impact of Mycorrhiza Application on Maize Plants (Zea Mays) Amended with Mineral and Organic Fertilizer. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etesami, H. The Dual Nature of Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria: Benefits, Risks, and Pathways to Sustainable Deployment. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2025, 9, 100421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeAngelis, K.M.; Lindow, S.E.; Firestone, M.K. Bacterial Quorum Sensing and Nitrogen Cycling in Rhizosphere Soil. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2008, 66, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fray, R.G. Altering Plant-Microbe Interaction through Artificially Manipulating Bacterial Quorum Sensing. Ann. Bot. 2002, 89, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennon, J.T.; Aanderud, Z.T.; Lehmkuhl, B.K.; Schoolmaster, D.R., Jr. Mapping the Niche Space of Soil Microorganisms Using Taxonomy and Traits. Ecology 2012, 93, 1867–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://californiaagriculture.org/article/111373.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Akinrinlola, R.J.; Yuen, G.Y.; Drijber, R.A.; Adesemoye, A.O. Evaluation of Strains for Plant Growth Promotion and Predictability of Efficacy by Physiological Traits. Int. J. Microbiol. 2018, 2018, 5686874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santillano-Cázares, J.; Turmel, M.-S.; Cárdenas-Castañeda, M.E.; Mendoza-Pérez, S.; Limón-Ortega, A.; Paredes-Melesio, R.; Guerra-Zitlalapa, L.; Ortiz-Monasterio, I. Can Biofertilizers Reduce Synthetic Fertilizer Application Rates in Cereal Production in Mexico? Agronomy 2021, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.vegetables.bayer.com/ca/en-ca/resources/agronomic-spotlights/rhizobium-inoculation-garden-beans.html#:~:text=occurring,were%20lower%20than%20in%20the (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Kalozoumis, P.; Ntatsi, G.; Marakis, G.; Simou, E.; Tampakaki, A.; Savvas, D. Impact of Grafting and Different Strains of Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria on Tomato Plants Grown Hydroponically under Combined Drought and Nutrient Stress. Acta Hortic. 2020, 1273, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, B.; Liu, T.; Xue, Z.; Cao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, M.; Liu, E.; Xing, J.; Wang, F.; Ren, X.; et al. Effects of Biofertilizer on Yield and Quality of Crops and Properties of Soil under Field Conditions in China: A Meta-Analysis. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.; Nazari, M.; Antar, M.; Msimbira, L.A.; Naamala, J.; Lyu, D.; Rabileh, M.; Zajonc, J.; Smith, D.L. PGPR in Agriculture: A Sustainable Approach to Increasing Climate Change Resilience. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 667546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Shen, Y.; Chen, C.; Chen, X.; Yang, X.; Liu, H.; Chen, R.; Liu, S.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, M.; et al. A Large-Scale Integrated Transcriptomic Atlas for Soybean Organ Development. Mol. Plant 2025, 18, 669–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Luo, Z.; Marand, A.P.; Yan, H.; Jang, H.; Bang, S.; Mendieta, J.P.; Minow, M.A.A.; Schmitz, R.J. A Spatially Resolved Multi-Omic Single-Cell Atlas of Soybean Development. Cell 2025, 188, 550–567.e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.-P.; Su, Y.; Jiang, S.; Liang, W.; Lou, Z.; Frugier, F.; Xu, P.; Murray, J.D. Applying Conventional and Cell-Type-Specific CRISPR/Cas9 Genome Editing in Legume Plants. Abiotech 2025, 6, 346–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Wang, J.; Shi, X.; Bai, M.; Yuan, C.; Cai, C.; Wang, N.; Zhu, X.; Kuang, H.; Wang, X.; et al. Genetically Optimizing Soybean Nodulation Improves Yield and Protein Content. Nat. Plants 2024, 10, 736–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulzen, J.; Abaidoo, R.C.; Mensah, N.E.; Masso, C.; AbdelGadir, A.H. Inoculants Enhance Grain Yields of Soybean and Cowpea in Northern Ghana. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rechiatu, A. Response of Soybean (Glycine max L.) to Rhizobia Inoculation and Molybdenum Application in the Northern Savannah Zones of Ghana. J. Plant Sci. (Sci. Publ. Group) 2015, 3, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.n2africa.org/learning-farmer-managed-soyabean-trials-kenya#:~:text=management%20was%20established%20on%2045,12%20t%20per%20ha%2C%20but (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Available online: https://www.farmtrials.com.au/view_attachment.php?trial_attachment_id=4689#:~:text=the%20cost%20of%20the%20product,generally%20retail%20for%20around%20%245%2Fha (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Bounaffaa, M.; Florio, A.; Le Roux, X.; Jayet, P.-A. Economic and Environmental Analysis of Maize Inoculation by Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria in the French Rhône-Alpes Region. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 146, 334–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.n2africa.org/sites/default/files/N2Africa_Market%20Analysis%20of%20Inoculant%20Production%20and%20Use_0_0.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2025).

| Phosphorus-Solubilizing Microbes | Estimated Increase in Yield | Crops | Conditions | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Penicillium bilaiae | ~3–7% | Legumes | Compared to untreated control | [91,92,93,94] |

| Bacillus (not only P-fixation effect led to yield increase) | ~6–9% | Maize, cotton | Field trials, drought conditions | [95] |

| ~52% | Tomato | Meta-analysis | [96] | |

| Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi | ~10–20% | Cereals | Field trials, inoculation in rainfed agriculture | [97,98,99,100] |

| ~10–30% | Vegetables | Field trials, compared to untreated control | [101,102,103] |

| PGPR | Estimated Yield Increase | Crops | Conditions | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PGPR + Bacillus safensis | ~5–16% | Wheat | Field trials, compared to untreated control | [127] |

| PGPR | ~90% | Tea | Field trials | [128] |

| ~47% | Strawberry | High-calcareous soil conditions | [129] | |

| ~15–20% | Legumes | Meta-analysis | [130] | |

| ~10–15% | Cereals | |||

| ~10–20% | Vegetables |

| Product (Brand) | Microbial Composition | Target Crop(s) | Cost (USD/ha) | Reported Yield Increase |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biofix (IITA) | Bradyrhizobium japonicum (USDA 110 strain) [173] | Soybean | ≈USD 1–2 (per 100 g pack) [176] | +19% (soybean) [171] |

| Legumefix (LT) | Bradyrhizobium japonicum (strain 532C) [171] | Soybean | ~USD 10.5 [172] | +12% (soybean) [171] |

| TagTeam™ (Novozymes) | Penicillium bilaii + Rhizobium (legume inoculant) [174] | Field peas, lentils, chickpea | ~USD 9.50 [174] | ≈+6% (field peas) [174] |

| JumpStart™ (Novozymes) | Penicillium bilaii (phosphate-solubilizing fungus) [174] | Wheat, barley, canola, sorghum | ~USD 12.50 [174] | +5% (wheat) [174] |

| Azospirillum inoculant | Azospirillum brasilense (e.g., strains Ab-V5/Ab-V6) [28] | Maize and other cereals | €20 to €60 [175] | +5.4% (maize) [28] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Palkina, K.A.; Choob, V.V.; Yampolsky, I.V.; Mishin, A.S.; Balakireva, A.V. Pros and Cons of Interactions Between Crops and Beneficial Microbes. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2526. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242526

Palkina KA, Choob VV, Yampolsky IV, Mishin AS, Balakireva AV. Pros and Cons of Interactions Between Crops and Beneficial Microbes. Agriculture. 2025; 15(24):2526. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242526

Chicago/Turabian StylePalkina, Kseniia A., Vladimir V. Choob, Ilia V. Yampolsky, Alexander S. Mishin, and Anastasia V. Balakireva. 2025. "Pros and Cons of Interactions Between Crops and Beneficial Microbes" Agriculture 15, no. 24: 2526. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242526

APA StylePalkina, K. A., Choob, V. V., Yampolsky, I. V., Mishin, A. S., & Balakireva, A. V. (2025). Pros and Cons of Interactions Between Crops and Beneficial Microbes. Agriculture, 15(24), 2526. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242526