Abstract

Soil erosion is a significant challenge to the environment, ecology, and economy, and areas that undergo fast land use change and climate change are the most affected. This research evaluates the effects that climate change and Land-Use/Land-Cover (LULC) change have, separately and together, on soil loss and sediment retention in the Lam Phra Phloeng (LPP) watershed, Thailand. The InVEST Sediment Delivery Ratio (SDR) model was applied under the Shared from Socioeconomic Pathways (SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5), using projected LULC for 2050 and 2100. The Cellular Automata–Markov (CA–Markov) model has been utilized to generate future land use/land cover (LULC) scenarios demonstrating how land changes over spatial and temporal scale. Results show a marked decline in sediment retention and a rise in soil loss, especially under high-emission scenarios and cropland expansion. By 2100, cropland soil loss increased by 57.35%, while forest cover—a key determinant of sediment retention—declined from 45.41% in 2020 to 22.19%. When climate and land-use changes are considered together, they have a much greater effect on sediment loss, especially in cropland and built-up areas. These results highlight the vital role that forest conservation and adaptive land management, e.g., afforestation and sustainable agriculture, play in ensuring the continued availability of clean water in watersheds and in erosion control. The research provides policy-makers with real-life scenarios to draw on when sketching integrated watershed management plans aimed at reducing the negative effects of land use and climate change on soil stability and water resources in the LPP watershed.

1. Introduction

Global problems concerning the environment, ecology, and economic infirmity are caused by soil erosion and have become more challenging in recent decades [1]. Past studies have shown that climate change and anthropogenic activities contribute to dramatic changes in sediment yield [2]. Soil and water loss from the watershed bring many problems, with extensive sediment deposition, increased environmental pollution, and decreased soil fertility. Soil erosion alters landscape quality and productivity and also has a significant effect on the natural ecosystems. Recent studies also emphasize that the scale of analysis, rainfall distribution, and lithological variability significantly influence landscape evolution, catchment morphology, and soil erosion patterns, particularly in regions like the western ghats [3]. Many researchers have observed that more than one-sixth of the global land cover is affected by soil erosion [4]. To develop a plan and policy regarding soil erosion and land management systems, policymakers need to quantify sediment yield at regional and catchment levels and evaluate the relative contribution from different land use/land cover types.

Identifying the factors responsible for soil loss is essential in sediment modeling to preserve soil at the catchment or regional level [5]. Models are the best tools for predicting the quantity of sediment yield and its transportation from land surface to water bodies, addressing the erosion issue, and suggesting the best management options for coping with it [6]. Different models are available for quantifying and modeling sediment yield and soil erosion mapping such as the agricultural non-point source model, Revised Universal Soil Loss Equation (RUSLE) [7]. Sediment River Network model (SedNet) [8]. The Natural Capital Project established the Integrated Valuation of Environmental Services and Tradeoffs (InVEST) model [9], which has been extensively adopted to model soil loss and sediment retention due to its flexibility, spatial explicitness, and accessibility. Compared to more complex models like SWAT and WEPP, In-VEST offers a more accessible yet robust framework for linking biophysical processes to land use/land cover decision-making. It is suitable for regional-scale assessments, particularly where data availability may be limited [9,10,11].

Quantifying future sediment yield and its governing factors is crucial for under-standing the biochemical cycle, soil erosion, soil fertility, water quality, and agricultural sustainability. Seasonal sediment load variations by both climatic shifts and anthropogenic activities have been observed in Indian basins, emphasizing the importance of trend and abrupt change analysis in sediment studies. Refs. [12,13] studied the trend of sediment yield in major rivers worldwide, observing a decline of more than 50% in river sediment yield. Human activities, sediment control structures, soil and water conservation, and reservoir building are the main reasons behind this trend. Ref. [14] found that global sediment flux decreases due to retention in the reservoir. Ref. [15] found that soil erosion threatened agricultural productivity and environmental sustainability, directly influencing people’s livelihood. Ref. [16] studied the check dams in the Rogativa catchment in Spain, identifying a significant decrease in sediment yield of 77%. Ref. [17] used remote sensing and census data to show long-term alterations in hydrology, while [18] quantified how agricultural expansion affects sediment and water budgets in the delta’s floodplain ecosystems.

While these global trends underscore the need for sustainable watershed management, the issue becomes even more critical in rapidly developing tropical countries like Thailand, where population growth, agricultural intensification, urbanization, and climate variability are placing increased pressure on water resources and land systems. Thailand’s watersheds, especially those in the north-eastern and central regions, are experiencing notable land use/land cover changes, driven by the expansion of cash crops like cassava and sugarcane, alongside rising water demands and intensified rainfall patterns. These dynamics make watershed-scale planning imperative for ensuring long-term agricultural productivity and ecosystem services. The Lam Phra Phloeng (LPP) watershed faces several environmental and hydrological challenges that require urgent scientific attention. One of the primary research problems in the LPP watershed is soil erosion, particularly in the upstream sections where deforestation and agricultural expansion have altered the natural landscape [19]. The conversion of forested areas into agricultural land for cash crops such as sugarcane and cassava has increased surface runoff, leading to sheet erosion and loss of topsoil [20]. This process negatively impacts soil fertility and contributes to sediment deposition in the LPP [21,22]. The steep slopes in the watershed exacerbate erosion, further threatening agricultural productivity and water quality. Although several studies in Thailand have explored either Land Use/Land Cover Change (LULC) or climate impacts on sediment yield, very few have examined their combined effects on both soil loss and sediment retention in an integrated framework. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in Thailand to apply the InVEST SDR model by integrating Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP) climate scenarios with a CA-Markov model for LULC projections in the LPP watershed. This novel integration allows for a more dynamic and realistic forecast of sediment dynamics under future socio-environmental scenarios, which has been largely lacking in previous Thai watershed studies.

Assessing the effects of climate and LULC changes on sediment yield is important in developing a strategic plan and policy for water resource management. Many studies have been executed to evaluate climate and LULC changes and impacts on sediment yield [23]. This study focuses on the combined impact of climate and LULC changes on both soil loss and sediment retention in the LPP watershed using the InVEST model. The integrated model was applied to future climatic scenarios (from 2021 to 2100) in a GIS platform and contrasted with a base scenario (1985–2020). This manuscript aims to quantify the extent of these changes in sediment retention and identify the areas of the region that are most affected. The findings of this study can provide meaningful insights for water resource planning and soil conservation, focusing on areas that require special attention.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

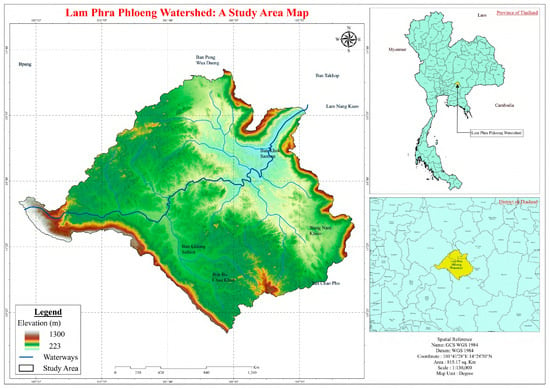

The LPP watershed is located in the northeast part of Thailand, as depicted in Figure 1. It encompasses a catchment area of approximately 820 km2. A key hydrological observation point is Station M.145, located at the outlet of the reservoir and managed by the Royal Irrigation Department (RID). This station plays a critical role in monitoring streamflow and water resource dynamics within the watershed. It records an average annual runoff of 241.93 million m3 yr−1 (241.93 × 106 m3 yr−1), which is the same as a mean discharge of around 7.67 m3 s−1 and a runoff depth of approximately 295 mm yr−1. The climate of the study area is typically tropical savannah affected by the monsoon. The annual rainfall is approximately 1140 mm/year, with a range of 925 to 1491 mm/year from 1990 to 2000. Most of the rainfall (80%) occurs from May to September [19]. The soil texture is predominantly silty loam with gently undulating loam soil. Some forested areas are protected, but the gradual encroachment of upland agriculture into the forested areas is evident. The reservoir has a storage capacity of approximately 106.30 million m3. It is vital to provide water assistance for agricultural cultivation within the project area, covering 75,524 ha during the rainy season. Additionally, it supplies water for the municipal water supply in Pak Thongchai district, Chok Chai district, and numerous rural communities, as well as for agricultural purposes outside the irrigation project area through natural water channels on an intermittent basis [22].

Figure 1.

Lam Phra Phloeng watershed Study Area Map.

The LPP watershed features steep, hilly terrain in its northern and eastern sections, which gradually flattens out into floodplains in the south, where the Lam Phra Phloeng Reservoir (LPPR) is situated. The elevation ranges from 220 m to 780 m above sea level, with upper catchment slopes over 25%. Additionally, intense monsoonal rainfall concentrated over a few months significantly increases surface runoff and sediment transport. These physical and climatic characteristics underscore the importance of assessing sediment dynamics in this region. Moreover, the growing pressure on LULC due to agricultural expansion into forested areas directly threatens the watershed’s ability to retain sediment, affecting both soil fertility and water quality downstream. Hence, this study area provides a representative and critical case for modeling soil loss and sediment retention under current and future climate and LULC scenarios.

2.2. Methodology

2.2.1. Study Workflow

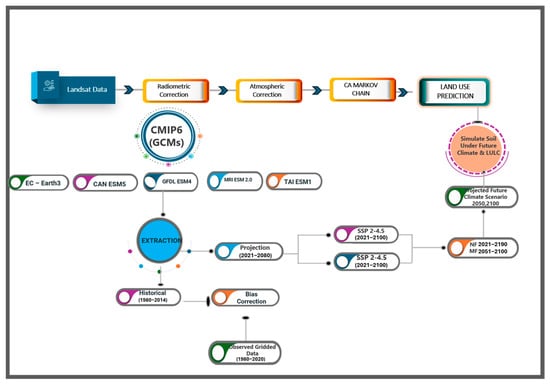

The main goal of this study is to examine the influence of individual and combined effects of climate and LULC changes on soil loss and retention in current and future scenarios, as illustrated in Figure 2. All five General Circulation Models used in this study are listed in Table 1. We first developed a baseline InVEST Sediment Delivery Ratio (SDR) model for the year 2020 using input datasets described in Table 2, then incorporated future LULC changes from the Cellular Automata (CA) Markov Chain model in the Land Change Modular (LCM). Additionally, we prepared future rainfall erosivity estimates by ensemble modeling of the five General Circulation Models (GCMs) listed in Table 1. These five bias-corrected GCMs provided predictions for future climate scenarios based on SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5, representing medium- and high-emission pathways, respectively.

Figure 2.

The study workflow.

InVEST (Integrated Valuation of Ecosystem Services and Tradeoffs) is a spatially explicit tool designed by the Natural Capital Project at Stanford University, in collaboration with partners such as the World Wildlife Fund, The Nature Conservancy, and others, for modeling ecosystem services. According to approach [3]. The InVEST model has been widely used for water yield and sediment retention, indicating a trend towards ecosystem-based adaptation strategies. Its Sediment Delivery Ratio (SDR) model estimates sediment export and retention based on LULC, topography, rainfall, and soil characteristics. CA–Markov modeling is a combination of CA, which simulates spatial changes using neighborhood rules, and Markov Chain models, which predict temporal transitions in state of LULC. This hybrid method is well-suited for projecting future LULC dynamics.

The InVEST SDR model estimates annual soil loss using the RUSLE and computes sediment export with a connectivity-based sediment delivery ratio. Sediment retention is calculated as the difference between soil loss and exported sediment.

The InVEST Sediment Delivery Ratio (SDR) model quantifies potential soil loss, sediment export, and retention using the “Revised Universal Soil Loss Equation” (RUSLE) framework and a sediment connectivity approach [24,25].

Here A, is the mean annual soil loss (t ha−1 yr−1), R is rainfall erosivity factor (megajoules millimeter per hectare per hour per year ha−1 h−1 yr−1), K is soil erodibility factor (t ha h ha−1 MJ−1 mm−1), LS represents slope length and steepness factor (dimensionless), C is the cover-management factor (dimensionless), and P is the support-practice factor (dimensionless).

The sediment export from each grid cell is calculated as follows:

represents the sediment delivery ratio of pixel x, calculated based on topographic connectivity.

where means maximum sediment delivery ratio (0.8–1.0); is the connectivity threshold; k represents the calibration parameter; and is the connectivity index of pixel x, determined by upslope area and downslope distance to the stream.

Sediment retention (SR) is precisely defined as:

This formulation links topography, vegetation cover, and land management to spatially explicit estimates of soil erosion and sediment retention across the watershed.

While the InVEST SDR model was applied rigorously to simulate soil loss dynamics in the LPP watershed, model calibration and validation were not conducted due to a lack of long-term sediment yield and flow data. This limitation, common in data-scarce regions, prohibited formal validation. Nevertheless, modeled trends were cross-validated quantitatively against previous sediment studies in the watershed, and parameterization followed peer review practices from similar tropical watersheds, ref. [26] applied the InVEST SDR model to assess ecosystem services under LULC and climate change in Kentucky, USA, without field sediment calibration, while [11] studied using the InVEST model in China, also without sediment field data for validation. Both [27] and [28] applied the InVEST sediment delivery model in the Mekong Delta without traditional model validation but used proxy indicators and expert judgements to interpret model outputs.

To evaluate the reliability of the model, both quantification and spatial validations were performed. The soil-loss rates predicted by the model were in line with the SDR and RUSLE estimates published for similar tropical basins (5–35 t yr−1) [11,26,27]; and therefore were within the credible ranges. A sensitivity analysis on SDR, comprising varied different major SDR parameters with distinct ranges (k = 0.25–0.50, IC0 = 0.10–0.60, SDRmax = 0.80–1.00) was performed with the values recommended in the InVEST User Guide Both [27]. Also, previous studies [11,26,27] identified that SDRmax was the most influential parameter, followed by IC0.

2.2.2. Data Used

To explore the range of impacts on LPP watersheds, we consider two, SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5, representing distinct future scenarios developed by the [29]. SSP2-4.5 assumes a ‘middle-of-the-road’ socio-economic development pathway with moderate mitigation efforts and stabilization of radiative forcing at 4.5 W/m2 by 2100. In contrast, SSP5-8.5 assumes rapid economic growth and high fossil fuel use, leading to radiative forcing of 8.5 W/m2, representing a high-emission, worst-case scenario. We used five General Circulation Models (GCMs), as listed in Table 1. The GCM data were statistically downscaled using the bias correction and quantile mapping method, which adjusts the modeled climate data to better match observed historical records, thereby reducing biases. Each GCM was selected based on strong regional performance in Southeast Asia.

For this analysis, we used two sets of climatic data: historical gridded ERA 5 (European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts [ECMWF]) data for daily precipitation from 1981 to 2020 and projected future precipitation from the bias-corrected results of GCMs from 2021 to 2100. We then summarized our results based on the baseline period (1981 to 2020) and two future time periods (2021–2050 and 2051–2100). The level of uncertainty has been reduced using various techniques, such as by ensembling five GCMs, to decrease the climate projection model.

Table 1.

Brief information on General Circulation Models data used.

Table 1.

Brief information on General Circulation Models data used.

| SN | GCM | Institute | Resolution (°) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | CanESM5 | Canadian Centre for Climate Modelling and Analysis, Victoria | 2.81 × 2.81 | [30] |

| 2. | EC-Earth3 | EC-Earth-Consortium, Europe | 0.70 × 0.70 | [31] |

| 3. | GFDL-ESM4 | NOAA-Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory (GFDL), USA | 1.25 × 1.00 | [32] |

| 4. | MRI-ESM2-0 | Meteorological Research Institute (MRI), Japan. | 1.13 × 1.12 | [33] |

| 5. | TaiESM1 | Research Center for Environmental Changes, Taiwan, China | 1.25 × 0.94 | [34] |

Table 2.

Input data and their sources.

Table 2.

Input data and their sources.

| Required Data | Data Source | URL |

|---|---|---|

| DEM | SRTM, USGS | https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/, accessed on 13 November 2025 |

| Study area mask | Hydrosheds | https://hydrosheds.org/, accessed on 13 November 2025 |

| Land use/Land cover (LULC) | ESRI | https://livingatlas.arcgis.com/landcover/, accessed on 13 November 2025 |

| Rainfall erosivity | ESDAC | https://esdac.jrc.ec.europa.eu/content/global-rainfall-erosivity, accessed on 13 November 2025 |

| Soil map | FAO | https://www.fao.org/soils-portal/data-hub/soil-maps-and-databases/faounesco-soil-map-of-the-world/en/, accessed on 13 November 2025 |

| Precipitation | ERA 5 gridded dataset | https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets (accessed on 13 November 2025) |

For future LULC prediction, a Cellular Automata-Markov Chain (CA-Markov) model was used in the TerrSet software (TerrSet liberaGIS v20.04). The classified LULC maps from 2003 and 2023 were employed to generate transition probability matrices, which quantify the likelihood of land cover type changes over time. The Markov Chain component captures temporal transitions, while CA component simulates spatial allocation by incorporating neighborhood effects. A suitability map was generated based on terrain and spatial contiguity to improve spatial realism in projected LULC patterns. The 2023 classification map was compared against the CA-Markov predicted map to validate the model’s accuracy. The change analysis and cubic trend were also performed to observe the transition of one class to another. Once validated, the model was used to project LULC for 2050 and 2100 as shown in Figure 2, capturing long-term landscape transformation trends under continued anthropogenic pressure.

To address uncertainties in climate projections, this study employed an ensemble approach using five GCMs representing a range of plausible future conditions under SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5. Bias correction through quantile mapping was applied to downscale and align model outputs with observed regional precipitation data. This ensemble method minimizes model-specific biases and captures inter-model variability, thereby increasing the robustness of rainfall erosivity estimates. The CA-Markov model was calibrated with two decades of observed LULC transitions for LULC projections and validated using accuracy assessment (overall accuracy = 89.3%, kappa 0.89). Although long-term ground-truth LULC data were limited, integrating machine learning classification (Random Forest) with trend-informed transition probability matrices helped constrain project uncertainties. The Random Forest method was chosen for its high classification accuracy and robustness to nonlinear, high-dimensional data [35]. RF can handle complex interactions among spectral, topographic, and ancillary variables, making it particularly suitable for the heterogeneous tropical landscape of the LPP watershed. It reduces overfitting by averaging the results of multiple decision trees, providing stable, reliable LULC classification performance compared with single-tree classifiers or parametric approaches. Combining ensemble modeling, historical trend calibration across eleven scenarios provides a structured treatment of uncertainty, supporting more reliable sediment retention forecasts under future conditions.

The precision of the CA–Markov LULC prediction has been assessed through the Kappa (κ) coefficient which measures the agreement between the simulated and observed Land-Use/Land-Cover (LULC) maps while also adjusting for the agreement that occurs by chance [36]. The Kappa (κ) coefficient measures agreement between classified and reference LULC maps while correcting for chance agreement. The Kappa statistic is expressed as:

where is the proportion of observed agreement and is the expected agreement occurring by chance. values range between 0 (no agreement) and 1 (perfect agreement). Values greater than 0.80 indicate excellent agreement, confirming that the CA–Markov model accurately reproduced historical LULC patterns in the LPP watershed.

To enhance model transparency, the CA–Markov configuration and validation results are summarized here. A 5 × 5 Moore neighborhood was applied, and slope, distance to roads, rivers, and population density were selected as suitability factors, each weighted using the Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP). The transition probability matrix was (from the 2000–2010–2020 LULC series) to project 2050 and 2100 scenarios. Model validation included Kappa (κ = 0.89) and the quantity/allocation disagreement indices [36], with Q = 0.031 and A = 0.045, indicating very little spatial misallocation. Class-wise User’s and Producer’s accuracies ranged from 85% to 94% (Table S1), and the complete confusion matrix is included in the Supplementary Materials.

2.2.3. Scenario Development

In this research, eleven scenarios were considered for analyzing sediment export and retention in the LPP watershed using the InVEST model, as mentioned in Table 3. All other physiographic parameters, such as soil erodibility (K), remain unchanged. These eleven scenarios combine climate and land use/land cover variables across three time periods and two emissions pathways (SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5) to capture a wide range of future possibilities.

Table 3.

Development of scenarios used for this study.

- A1 serves as the baseline (2020 climate and 2020 LULC).

- A2–A5 simulate future climate (2050 and 2100) under both SSPs, with static 2020 land use to isolate climate effects.

- A6–A9 combine future climate and projected land use/land cover (2050 and 2100) to assess interactive effects.

- A10 and A11 isolate the impact of land use/land cover change by holding climate constant (2020) and modifying LULC.

These scenarios help to observe the relative contribution of anthropogenic LULC change versus climatic forcing, particularly useful in contexts where land use pressures may outweigh direct climate impacts. The main differences lie in whether the model isolates single drivers (climate only or LULC only) versus combined scenarios, and how future years (2050 vs. 2100) and pathways (SSP 2-4.5 vs. SSP5-8.5) are contrasted to reveal both temporal and intensity-based divergence. These combinations enable a systematic assessment of the relative and combined influence of climate and LULC on soil erosion and sediment retention.

While the InVEST SDR and CA–Markov models were applied rigorously to simulate soil loss and LULC change dynamics in the LPP watershed, this study faced several limitations related to model validation and calibration. Specifically, the absence of long-term ground-based sediment yield and runoff data precluded formal quantitative validation of the InVEST model outputs. As a result, sediment estimates could not be directly calibrated against observed field measurements. To address this, parameter settings were adopted from established literature and comparable watershed studies within tropical Southeast Asia, ensuring methodological consistency.

Similarly, validation of the CA–Markov LULC projections was constrained by the lack of historical georeferenced land change datasets. Although an accuracy assessment was performed for the 2023 land cover classification, yielding an overall accuracy of 89.3% and a Kappa coefficient of 0.89, further temporal validation was not possible due to data limitations. These constraints are acknowledged as a limitation of the current study.

Despite these challenges, qualitative consistency between model outputs and documented trends in sedimentation and LULC change reported in previous studies such as [19,37] provides a degree of validation. Additionally, the use of ensemble climate projections, bias correction techniques, and scenario-based analysis helps mitigate uncertainty and improve the reliability of the results within a planning and policy context.

2.2.4. Model Limitations

Several limitations should be noted for this study. First, the absence of long-term sediment yield and runoff data prevented formal calibration of the InVEST SDR model. Second, uncertainties in GCM projections may persist despite bias correction, particularly regarding the representation of rainfall intensity. Third, potential classification errors in land use/land cover maps and inaccuracies in transition probabilities derived from remote sensing could reduce accuracy for minor land cover classes. The model is also sensitive to key parameters, such as SDRmax and IC0, which may introduce variability in soil loss estimates. Finally, discrepancies in spatial resolution between climate data (0.05°) and LULC data (30 m) may affect the reliability of local-scale erosion assessments.

3. Results

3.1. Climate Change Scenario

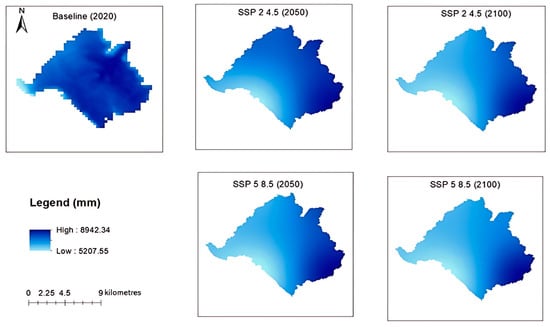

Climate change significantly influences sediment dynamics by altering precipitation patterns, runoff, and soil erosion rates. The analysis of future climate scenarios, SSP 2-4.5 and SSP 5-8.5, indicates a decrease in annual precipitation variability, directly impacting soil loss and sediment retention in the LPP watershed. While several studies across Southeast Asia show stronger precipitation extremes under the SSP 5-8.5 scenario [38], the bias-corrected ensemble indicates a modest decrease in basin-mean rainfall erosivity (R), with mixed behavior in extreme-rainfall indicators (P99 intensity and storm frequency differ among models) [39]. A comparison with Thai Meteorological Department (TMD) station data shows that baseline annual precipitation and high-percentile intensity are reproduced within about 10–15%, although variability among models remains considerable. Accordingly, this study interprets the projected decline in R cautiously—mean erosivity decreases slightly, whereas extreme-rain indicators do not uniformly decline—highlighting uncertainty in future erosivity responses.

Figure 3 illustrates the spatial distribution of rainfall erosivity (R) across the LPP watershed. The spatial distribution of R in the LPP watershed was analyzed for the mid-century (2050) and end-century (2100) periods under SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 scenarios. The data is presented in MJ mm ha−1 h−1 yr−1 and averaged over 30-year periods (2021–2050, 2071–2100). The analysis used a bias-corrected and downscaled GCM ensemble at a resolution of 0.05° (~5 km). Water bodies and non-vegetated areas were excluded from the analysis.

Figure 3.

Spatial distribution of rainfall erosivity (MJ mm ha−1 h−1 yr−1) across the LPP watershed for the baseline (2020), SSP 2 4.5 (2050), SSP 2 4.5 (2100), SSP 5 8.5 (2050), and SSP 5 8.5 (2100).

A key observation from all scenarios is that rainfall erosivity is consistently higher in the eastern part of the watershed. This can be attributed to orographic effects due to the higher elevations and slope gradients in that region, which amplify rainfall impact energy. In contrast, the western region shows relatively lower R values due to flatter terrain and forest cover that buffers rainfall impact. These spatial patterns emphasize the importance of localized topography in controlling erosivity. The consistency of these spatial trends across five ensemble GCMs also enhances confidence in the model outputs. This is justified based on a study by [28] who emphasized that LULC and rainfall are key drivers of sediment yield variability and demonstrated the use of sensitivity analysis to inform model inputs for more reliable assessment.

Model reliability was ensured through ensemble averaging of five GCMs, bias correction using quantile mapping, and spatial validation of baseline rainfall erosivity with observed data from Thai Meteorological Department (TMD) stations. The InVEST SDR model was calibrated by comparing modeled 2020 soil loss with reported sedimentation trends in the LPP reservoir from [19,37]. The alignment of spatial patterns and magnitude provided validation confidence.

Under the baseline (A1), crop areas exhibit the highest soil loss (1.45 million tons yr−1), followed by built-up (0.58 million tons yr−1). Forests and water bodies contribute considerably less (0.07 and 0.08 million tons yr−1, respectively), reflecting their stronger protective functions. In terms of sediment retention, forests dominate with over 84.7 million tons yr−1, nearly four times higher than any other class, highlighting their critical role in regulating sediment dynamics.

Future climate scenarios show a consistent decline in both soil loss and sediment retention. By 2050 under SSP2-4.5 (A2), soil loss decreases by ~4–5% across all classes, while sediment retention drops by 2.7–5.9%. By 2100 (A3), these reductions deepen, reaching 9–10% for soil loss and 7–10% for retention. Under SSP5-8.5 (A4), which represents a high-emission pathway, reductions are even sharper: soil loss decreases by 12–13% and sediment retention by 11–14%. Interestingly, the far-future SSP5-8.5 scenario (A5, 2100) exhibits a slightly lower reduction compared to A4, with declines of ~8–11% for soil loss and 9–12% for sediment retention. This suggests potential nonlinear responses of soil-erosion processes under extreme climatic forcing.

Overall, the results emphasize three key insights as climate change reduces both soil loss and retention capacity, though the magnitude varies by scenario and land cover; forests are the most effective in retaining sediments, but they too face significant declines under climate stress; and high-emission scenarios amplify reductions, with built-up and crop areas particularly vulnerable. These findings from Table 4 underline the importance of conserving forested landscapes and adopting sustainable land management to buffer against erosion risks in future climates.

Table 4.

Total soil loss and sediment retention in different scenarios of climate change and % change from A1.

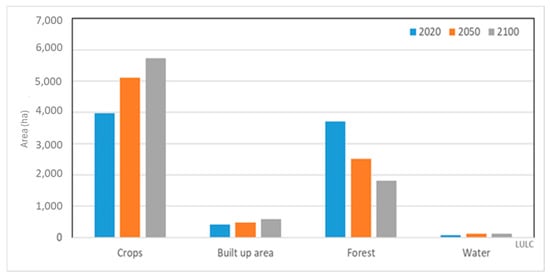

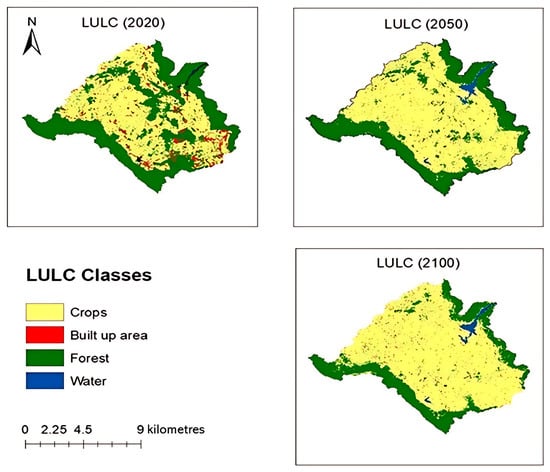

3.2. Simulation of Land Use/Land Cover Change

LULC changes are significant anthropogenic stressors influencing sediment transport and retention in the LPP watershed. Figure 4 depicts that area covered by cropland has increased from 3900 ha (39 km2) in 2020 to 5700 ha (57 km2) by 2100, which is representing about 46% of the ~820 sq.km watershed. Built-up areas also expanded slightly as per the projected reflecting the continuation of urbanization in future. Conversely, forest cover declines from about 3700 ha in 2020 to roughly 1800 ha by 2100, indicating substantial deforestation. Water bodies show only a minor change, remaining below 200 ha throughout the projection period. These trends show that agricultural expansion and urban growth are the dominant land-use transition factors, which poses potential risks to sediment regulation, water quality, and ecosystem sustainability across the basin.

Figure 4.

The predicted land-use/land-cover (LULC) composition is shown for SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5. The years shown are the baseline year (2020), mid-century (2050), and end-century (2100). The units are in area (ha). The data resolution is 30 m, which comes from Landsat classification. Each scenario year is based on averages for each decade.

These projections were derived using the CA–Markov model in the TerrSet platform. The 2023 LULC map was classified using the Random Forest (RF) classifier with 500 trees, selected for its high accuracy and robustness in heterogeneous tropical landscapes. Accuracy assessment was performed using confusion matrix and Kappa coefficient (κ = 0.89), with ground-truth samples from 2023 Landsat OLI imagery validated against Google Earth. The transition probability matrix for future years was derived from 2003–2023 data.

Figure 5 illustrates the spatial distribution of LULC changes between 2020 and 2100, highlighting significant cropland expansion and a corresponding reduction in forest cover. The drivers of this transition include rising cassava and sugarcane demand (linked to biofuel policy), urban growth in Chok Chai and Pak Thong Chai districts, and limited enforcement of forest protection zones. Government incentives promoting cash crops and fragmented land tenure further exacerbate LULC transitions. The anticipated decline in forested areas is expected to significantly reduce sediment retention capacity, leading to elevated erosion rates in agricultural zones. This trend is consistent with findings by [40] who reported that the conversion of forests to plantations in Thailand increased sediment transport and diminished watershed services.

Figure 5.

Spatial distribution of LULC change that is observed for the period baseline 2020, 2050, and 2051 crops, built-up area, forest and water.

Table 5 shows that under the baseline (A1), crop areas again dominate soil loss (1.45 million tons yr−1), followed by built-up areas (0.58 million tons yr−1), with forests and water contributing marginally. Forests remain the most effective sink for sediment retention (84.7 million tons yr−1).

Table 5.

Total soil loss and sediment retention under different scenarios of LULC change and % change from A1.

By 2050 (A10), LULC changes substantially alter erosion dynamics. Soil loss from crops and built-up areas rises sharply, by ~31% and ~122%, respectively, indicating the expansion of agricultural and urban land. Forest and water areas exhibit mixed responses: soil loss increases modestly (26% in forests) but decreases by ~48% in water zones, likely due to reduced extent of water bodies. Sediment retention patterns are similarly contrasting: retention decreases significantly in crops (−32%) and built-up (−35%), while forests show a small increase (+11%), and water retention declines (−38%). These results highlight the uneven trade-offs of land conversion, where increased cropland and urbanization drive higher erosion, while forest stability offers partial buffering.

By 2100 (A11), the effects intensify. Soil loss from croplands nearly doubles (−57% relative change), and built-up areas rise by ~56%, reflecting long-term expansion pressures. Forest and water zones show continued increases in soil loss (~31% and ~26%, respectively). Sediment retention responses diverge: croplands drop by ~28%, built-up areas retain slightly more (+7%), forests decrease by ~17%, and water declines by ~21%.

Overall, these findings demonstrate that LULC change exerts stronger impacts than climate alone. Croplands and built-up areas are particularly vulnerable hotspots of erosion, while forests, despite their buffering role, lose retention capacity under extensive conversion. The results underscore the need for sustainable land use/land cover planning to mitigate erosion and preserve sediment regulation services in future landscapes.

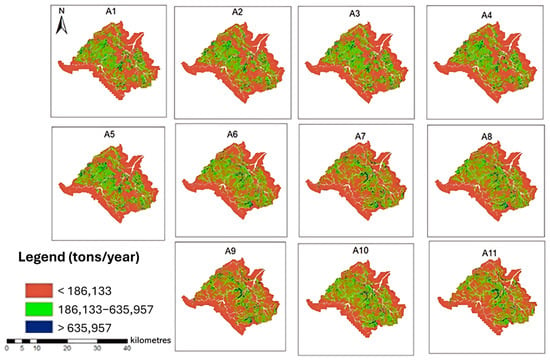

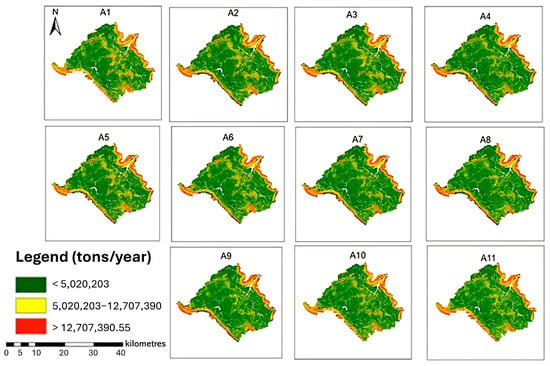

3.3. Combined Impact of Climate and LULC Change on Soil Loss and Sediment Retention

Figure 4 and Figure 5 present the spatial distribution of soil loss and sediment retention under combined scenario simulations. Figure 6 represents A1–A11 soil loss simulations with changing climate and LULC inputs. Figure 7 represents sediment retention under both climate and LULC changes. The key difference lies in the input assumptions A6–A9 simulate actual projected LULC transitions, hence show higher soil loss intensities due to forest-to-crop conversion. The soil loss values are up to 20× higher in Figure 6 due to compounded effects.

Figure 6.

Spatial distribution of modeled soil loss (A1–A11) in the LPP watershed under SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 scenarios for 2020, 2050, and 2100. Units: t ha−1 yr−1; 30-year mean (2021–2050, 2071–2100); Model resolution: 30 m grid; Masked areas: urban zones and open water excluded.

Figure 7.

Sediment retention capacity for scenarios (A1–A11): (A1) (Baseline 2020), (A2) (SSP2-4.5 2050), (A3) (SSP2-4.5 2100), (A4) (SSP5-8.5 2050), (A5) (SSP5-8.5 2100), (A6) (SSP2-4.5 2050 LULC), (A7) (SSP2-4.5 2100 LULC), (A8) (SSP5-8.5 2050 LULC), (A9) (SSP5-8.5 2100 LULC), (A10) (LULC 2050), (A11) (LULC 2100). Units: t yr−1; 30-year mean; 30 m resolution; non-productive areas masked.

These results align with the findings by [10], who demonstrated that LULC changes, particularly deforestation, can lead to considerable reductions in soil conservation services in arid regions. Additionally, ref. [26] emphasized that LULC changes exert a more pronounced influence on sediment retention than climate change alone, underscoring the importance of maintaining vegetative cover to mitigate soil erosion. Scenario A11 reflects even more severe outcomes, with sediment retention declining further and soil loss escalating across all LULC categories, particularly within croplands. These trends align with research by [11], which highlighted that the synergistic interaction between extreme climatic conditions and landscape modifications intensifies soil degradation and deteriorates water quality.

The combined impact of climate change and LULC modifications presents the most severe scenario for the LPP watershed [19]. When both drivers are considered together, the study shows drastic increases in soil loss across all LULC types, with croplands and built-up areas experiencing the highest surge [41]. Concurrently, sediment retention significantly diminishes, particularly in forested areas, highlighting the compounded effects of climatic and anthropogenic stressors on soil erosion processes [10]. These results suggest that without effective intervention, the cumulative impact of climate and LULC changes could substantially degrade soil conservation services, posing risks to water quality, agricultural productivity, and overall ecosystem resilience [15].

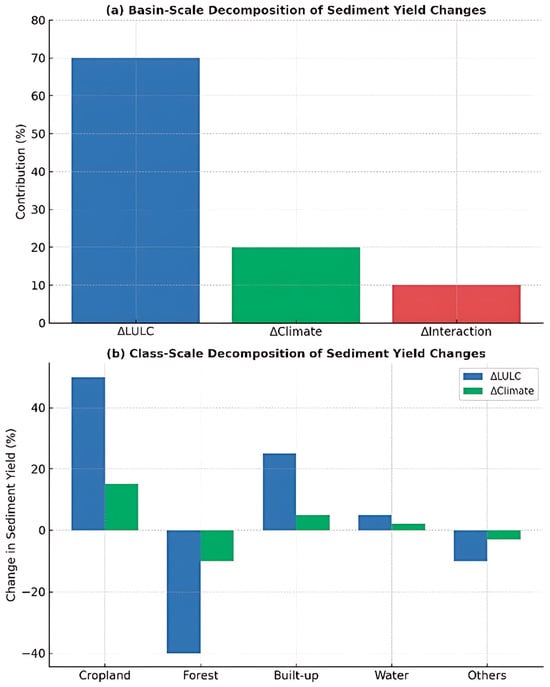

3.4. Attribution of Sediment Change Drivers

To quantitatively distinguish the relative effects of Land-Use/Land-Cover (LULC) change and climate variability on sediment yield, a simple factorial decomposition was applied. Based on the simulation results, four scenarios were evaluated: a baseline (A1), changes to climate only (A2: climate from 2030 with LULC from 2020), changes to land use/land cover only (A3: future LULC with baseline climate), and a combination of both (A4: future LULC and climate). Sediment yield differences were calculated as changes relative to A1, and the total variation was divided as follows [36]:

ΔTotal = ΔLULC + ΔClimate + ΔInteraction

At the basin scale, LULC change explained about 70% of total sediment variation, climate change 20%, and interaction 10% (Figure 8a). This confirms that LULC dynamics—especially cropland expansion and forest loss—are the main drivers of increased sediment yield, while climate-driven changes in rainfall erosivity act as secondary modifiers.

Figure 8.

Factorial decomposition of sediment yield changes in the LPP watershed. (a) Basin-scale attribution showing the relative contributions of LULC, climate, and interaction effects. (b) Class-scale changes in sediment yield (%) by LULC category, distinguishing LULC- and climate-driven components under SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 scenario.

At the class scale (Figure 8b), cropland and built-up areas exhibit the largest sediment increases (ΔLULC ≈ +50% and +25%), whereas forested areas show a strong decline (ΔLULC ≈ −40%). Climate change has a limited (under ±15%) impact on all categories. The data supports the idea that LULC change is the main factor in sediment yield under SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 scenarios.

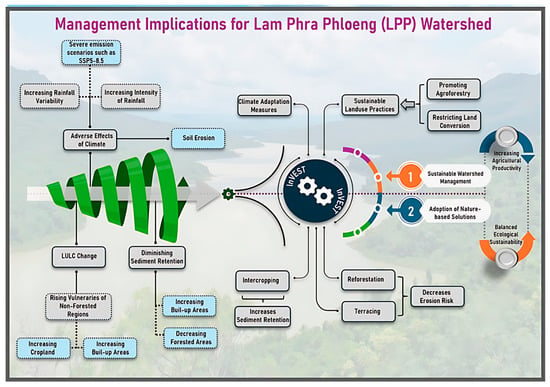

3.5. Management Implications

The findings from this study highlight the pressing need for sustainable watershed management strategies in the LPP watershed. Figure 9 summarizes the interlinkages between climate drivers, LULC change, sediment dynamics, and intervention strategies, offering a systemic view of pressures and solutions for improving watershed health.

Figure 9.

Management implications for Lam Phra Phloeng Watershed.

As shown in Figure 9, severe climate emission pathways (e.g., SSP5-8.5) result in increased rainfall variability and intensity, two key factors that intensify soil erosion processes across the landscape [29,42]. These climatic stressors, combined with anthropogenic LULC changes, especially the expansion of croplands and built-up areas are found to significantly reduce sediment retention capacity and elevate erosion risk, particularly in non-forested regions [15,26].

The diagram emphasizes the cascading nature of these changes: climate stressors exacerbate adverse environmental effects (e.g., runoff and soil detachment), while LULC transitions (e.g., deforestation) reduce landscape resilience, further diminishing sediment retention [8,9]. This synergistic degradation calls for a two-pronged management strategy grounded in both climate adaptation and sustainable land use/land cover practices [10,11].

On the adaptation front, nature-based solutions (NbS) such as reforestation, intercropping, and terracing are highlighted in Figure 7 for their ability to enhance sediment retention and stabilize hillslopes [40]; refs. [4,43] demonstrated how NbS like urban parks can enhance hydrological ecosystem services, linking green infrastructure to co benefits such as water retention and microclimate regulation in Vietnam. These interventions can directly reduce erosion risks by improving vegetative cover and increasing infiltration capacity, thus buffering the effects of extreme precipitation.

Simultaneously, sustainable land use/land cover practices must be institutionalized to ensure long-term resilience. These include promoting agroforestry, restricting land conversion in erosion-prone areas, and enforcing zoning laws to protect remaining forested landscapes [7,19]. These strategies support not only ecological stability but also agricultural productivity, creating co-benefits for food security and local livelihoods [14,16]. Studies from [44,45,46] explored how household-level adaptation, including adoption of ecological shrimp aquaculture or diversified cropping system, can modulate the benefits derived from ecosystem services and reduce vulnerability. The management framework presented is also aligned with national initiatives such as Thailand’s Forest Landscape Restoration Strategy (FLR 2560) and emerging Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES) programs, which promote incentive-based conservation [47]. Contextualizing such measures within local governance systems, tenure arrangements, and community capacities is crucial for implementation success.

In summary, Figure 9 advocates a dual-pathway response: Sustainable Watershed Management, focusing on policy-driven land use/land cover planning, and Adoption of Nature-based Solutions, emphasizing low-cost, ecologically adaptive measures. Together, these strategies aim to balance ecological sustainability with socio-economic development, strengthening the long-term resilience of the LPP watershed to both climatic and anthropogenic pressures.

4. Conclusions

The findings from this study emphasize the profound influence of climate change and LULC changes on soil loss and sediment retention within the LPP watershed. While the study applied InVEST SDR and CA–Markov models rigorously, a more objective discussion of limitations is necessary to strengthen credibility. Beyond the lack of long-term sediment and runoff data for calibration, uncertainties arise from parameter transferability across watersheds, spatial resolution of input datasets, and assumptions of static socio-economic drivers in LULC projections. These factors may influence the precision of soil loss and retention estimates. Acknowledging these constraints emphasizes that results should be interpreted as indicative trends rather than absolute values, thereby underscoring the importance of integrating field monitoring and multi-model comparisons in future research. The application of the InVEST model, combined with future climate projections and LULC scenarios, provides valuable insights into the dynamic interplay between anthropogenic activities and environmental factors influencing sediment dynamics. The results reveal that climate change alone (A2–A5), particularly under severe emission scenarios such as SSP5-8.5, significantly exacerbates soil erosion due to increased rainfall intensity and variability. Cropland and built-up areas, in particular, exhibited pronounced increases in soil loss, with forested areas offering some resistance due to their inherent sediment retention capacity. The rising vulnerability of non-forested regions emphasizes the need for targeted land management interventions to mitigate soil degradation. The LULC projections indicate that by 2100, croplands are expected to cover over 70% of the watershed, while forested areas are projected to decline to just 22.19%. This transition significantly diminishes the watershed’s natural capacity to retain sediment, leading to an alarming increase in soil loss, particularly in urban and agricultural zones. Such findings enhance the critical role that forest conservation and sustainable land management practices play in maintaining soil stability and ecosystem health.

Recent research in Thailand demonstrates that the dual imperatives increasingly inform watershed management efforts in terms of climate adaptation and sustainable land use. The Songkhram River Basin highlights the value of integrating assessments of land-use and climate change impacts on sediment yield, revealing that conservation scenarios can significantly reduce sediment yield compared to economic alternatives. In the Hui Ta Poe watershed, ecosystem-based adaptation measures, such as reforestation and filter strips, have reduced sediment yield by up to 88%, demonstrating their effectiveness in maintaining ecosystem stability. Moreover, findings from the Mun River Basin emphasize that combining mechanical and soil-water conservation practices is crucial to counteract increased erosion resulting from rapid land cover changes and extreme weather events. Collectively, these studies highlight the need for comprehensive management frameworks that safeguard both ecological health and climate resilience in Thailand’s watersheds.

Future initiatives should also focus on community-level engagement, pilot-scale interventions, and participatory planning frameworks to test the feasibility and acceptance of conservation practices. Encouraging local stakeholders to co-develop land-use solutions can bridge the gap between scientific recommendations and on-ground action. Furthermore, integrating socio-economic dimensions such as land tenure systems, market access, and farmer incentives into hydrological and land-use models will foster more holistic, inclusive, and adaptive watershed governance strategies.

Ultimately, this study’s findings hold strong policy relevance. It provides scientific evidence for decision-makers to prioritize climate-resilient land management, allocate resources for ecological restoration, and design regulatory frameworks that balance environmental protection with agricultural development. As climate and land pressures intensify, informed and locally adapted watershed policies will safeguard the LPP watershed and ensure long-term water security, soil health, and socio-ecological resilience. Long-term sediment yield and transport data collection for quantitative validation of the InVEST SDR model should be the main focus of future research, coupled with the use of high-resolution remote sensing datasets for better LULC change projections, and the investigation of socioeconomic and policy drivers that are affecting land-use transitions in the LPP watershed.

5. Recommendations

Future research should focus on collecting long-term sediment yield and runoff data to validate the InVEST SDR model. Employ high-resolution remote sensing or field measurements to enhance LULC change projections. Explore the socio-economic factors driving land use change (e.g., crop demand, urbanization) to improve scenario analyses.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agriculture15232511/s1, Table S1. Confusion Matrix and Accuracy Assessment for the Hindcast 2020 LULC Simulation Using the CA–Markov model.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: U.S., R.M., A.K. and S.V.S.A.B.G.; Methodology: U.S., R.M., A.L.G. and S.V.S.A.B.G.; Software: R.M.; Validation, R.M. and A.L.G.; Formal analysis: R.M. and P.T.; Data curation: U.S. and R.M.; Writing—original draft: R.M. and P.T.; Writing—review and editing: U.S., R.M., A.L.G., A.K. and S.V.S.A.B.G.; Visualization: R.M., P.T. and S.V.S.A.B.G.; Supervision: U.S.; Project administration: U.S.; Funding acquisition: U.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available satellite and climate datasets were used in this study. These data can be accessed from the following sources: SRTM DEM from USGS (https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/, accessed on 13 November 2025), ERA5 climate data from ECMWF (https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets, accessed on 13 November 2025), and land use/land cover data from ESRI Living Atlas (https://livingatlas.arcgis.com/landcover/, accessed on 13 November 2025).

Acknowledgments

Thanks to colleagues and staff from AIT and KMITL and others that slightly contribute to the research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Briak, H.; Moussadek, R.; Aboumaria, K.; Mrabet, R. Assessing sediment yield in Kalaya gauged watershed (Northern Morocco) using GIS and SWAT model. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2016, 4, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Fan, W.; Li, Y.; Yi, Y. The influence of changes in land use and landscape patterns on soil erosion in a watershed. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 574, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Loc, H.H.; Pal, I.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; Huynh, T.V.P.; Pham, D.T.; Thi, H.C.N. Assessing the sensitivity of physiographical parameters in modeling hydrological ecosystem services that support food security: The case of Vietnamese Mekong Delta. Model Earth Syst. Environ. 2025, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İlay, R.; Kavdir, Y. Impact of land cover types on soil aggregate stability and erodibility. Environ. Monit Assess. 2018, 190, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yesuf, H.M.; Assen, M.; Alamirew, T.; Melesse, A.M. Modeling of sediment yield in Maybar gauged watershed using SWAT, northeast Ethiopia. Catena 2015, 127, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, D.; Harvey, C.; Resosudarmo, P.; Sinclair, K.; Kurz, D.; McNair, M.; Crist, S.; Shpritz, L.; Fitton, L.; Saffouri, R.; et al. Environmental and economic costs of soil erosion and conservation benefits. Science 1995, 267, 1117–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watene, G.; Yu, L.; Nie, Y.; Zhu, J.; Ngigi, T.; Nambajimana, J.d.D.; Kenduiywo, B. Water Erosion Risk Assessment in the Kenya Great Rift Valley Region. Sustainability 2021, 13, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Joseph, S.; Thrivikramji, K.P. Assessment of soil erosion in a monsoon-dominated mountain river basin in India using RUSLE-SDR and AHP. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2018, 63, 542–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, X.; Wang, X.; Yan, H.; Zhang, Q.; Jin, G. Land Use/Land Cover Change Induced Impacts on Water Supply Service in the Upper Reach of Heihe River Basin. Sustainability 2015, 7, 366–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Li, B.; Hou, Y.; Bi, X.; Zhang, X. Effects of land use and climate change on ecosystem services in Central Asia’s arid regions: A case study in Altay Prefecture, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 607, 633–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, R.; Yu, D.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Qiao, J.; Wang, X.; Du, J. Impacts of changes in climate and landscape pattern on ecosystem services. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 579, 718–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Banerjee, S. Investigation of changes in seasonal streamflow and sediment load in the Subarnarekha-Burhabalang basins using Mann-Kendall and Pettitt tests. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walling, D.E.; Fang, D. Recent trends in the suspended sediment loads of the world’s rivers. Glob. Planet. Change 2003, 39, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syvitski, J.P.M.; Vörösmarty, C.J.; Kettner, A.J.; Green, P. Impact of humans on the flux of terrestrial sediment to the global coastal ocean. Science 2005, 308, 376–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Klik, A.; Mu, X.; Wang, F.; Gao, P.; Sun, W. Sediment yield estimation in a small watershed on the northern Loess Plateau, China. Geomorphology 2015, 241, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boix-Fayos, C.; De Vente, J.; Martínez-Mena, M.; Barberá, G.G.; Castillo, V. The impact of land use change and check-dams on catchment sediment yield. Hydrol. Process. Int. J. 2008, 22, 4922–4935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, T.R.; Park, E.; Loc, H.H.; Tien, P.D. Long-term hydrological alterations and the agricultural landscapes in the Mekong Delta: Insights from remote sensing and national statistics. Environ. Chall. 2022, 7, 100454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Ho, H.L.; Van Binh, D.; Kantoush, S.; Poh, D.; Alcantara, E.; Try, S.; Lin, Y.N. Impacts of agricultural expansion on floodplain water and sediment budgets in the Mekong River. J. Hydrol. 2022, 605, 127296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirikaew, U.; Seeboonruang, U.; Tanachaichoksirikun, P.; Wattanasetpong, J.; Chulkaivalsucharit, V.; Chen, W. Impact of Climate Change on Soil Erosion in the Lam Phra Phloeng Watershed. Water 2020, 12, 3527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oduor, B.O.; Mutua, B.M.; Gathagu, J.N.; Wambua, R.M. Evaluation of the Streamflow Response to Agricultural Land Expansion in the Thiba River Watershed in Kenya. Agric. Rural. Stud. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Song, Z.; Yu, B.; Fan, Y.; Tony, V.; Guo, L.; Li, Q.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; et al. Land use changes and edaphic properties control contents and isotopic compositions of soil organic carbon and nitrogen in wetlands. Catena 2024, 241, 108031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wattanasetpong, J.; Seeboonruang, U.; Sirikaew, U.; Chen, W. Assessment of land cover on soil erosion in Lam Phra Phloeng watershed by USLE model. MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 192, 02017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Collins, D.B.G.; Bras, R.L. Climatic control of sediment yield in dry lands following climate and land cover change. Water Resour. Res. 2008, 44, 10405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, R.; Chaplin-Kramer, R.; Wood, S.A.; Guerry, A. InVEST 3.2.0 User’s Guide. Available online: https://storage.googleapis.com/releases.naturalcapitalproject.org/invest-userguide/latest/en/index.html (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Borselli, L.; Cassi, P.; Torri, D. Prolegomena to sediment and flow connectivity in the landscape: A GIS and field numerical assessment. Catena 2008, 75, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Ochuodho, T.O.; Yang, J. Impact of land use and climate change on water-related ecosystem services in Kentucky, USA. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 102, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, N.A.; Benavidez, R.; Tomscha, S.A.; Nguyen, H.; Tran, D.D.; Nguyen, D.T.H.; Loc, H.H.; Jackson, B.M. Ecosystem Service Modelling to Support Nature-Based Flood Water Management in the Vietnamese Mekong River Delta. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Pal, I.; Loc, H.H. Modeling the impacts of climate and land use changes on nutrient export using the INVEST model in Tra Vinh Province of the Vietnamese Mekong Delta. In The Mekong Delta Environmental Research Guidebook; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 349–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC AR6, Climate Change Synthesis Report. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/ (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Swart, N.C.; Cole, J.N.S.; Kharin, V.V.; Lazare, M.; Scinocca, J.F.; Gillett, N.P.; Anstey, J.; Arora, V.; Christian, J.R.; Hanna, S.; et al. The Canadian Earth System Model version 5 (CanESM5.0.3). Geosci. Model Dev. 2019, 12, 4823–4873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döscher, R.; Acosta, M.; Alessandri, A.; Anthoni, P.; Arsouze, T.; Bergman, T.; Bernardello, R.; Boussetta, S.; Caron, L.-P.; Carver, G.; et al. The EC-Earth3 Earth system model for the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project 6. Geosci. Model Dev. 2022, 15, 2973–3020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunne, J.P.; Horowitz, L.W.; Adcroft, A.J.; Ginoux, P.; Held, I.M.; John, J.G.; Krasting, J.P.; Malyshev, S.; Naik, V.; Paulot, F.; et al. The GFDL Earth System Model Version 4.1 (GFDL-ESM 4.1): Overall Coupled Model Description and Simulation Characteristics. J. Adv. Model Earth Syst. 2020, 12, e2019MS002015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukimoto, S.; Kawai, H.; Koshiro, T.; Oshima, N.; Yoshida, K.; Urakawa, S.; Tsujino, H.; Deushi, M.; Tanaka, T.; Hosaka, M.; et al. The Meteorological Research Institute Earth System Model Version 2.0, MRI-ESM2.0: Description and Basic Evaluation of the Physical Component. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. Ser. II 2019, 97, 931–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.-L.; Wang, Y.-C.; Shiu, C.-J.; Tsai, I.-C.; Tu, C.-Y.; Lan, Y.-Y.; Chen, J.-P.; Pan, H.-L.; Hsu, H.-H. Taiwan Earth System Model Version 1: Description and evaluation of mean state. Geosci. Model Dev. 2020, 13, 3887–3904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontius, R.G.; Millones, M. Death to Kappa: Birth of quantity disagreement and allocation disagreement for accuracy assessment. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2011, 32, 4407–4429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorsirirat, K. Effect of Forest Cover Change on Sedimentation in Lam Phra Phloeng Reservoir, Northeastern Thailand. In Forest Environments in the Mekong River Basin; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supharatid, S.; Aribarg, T.; Nafung, J. Bias-corrected CMIP6 climate model projection over Southeast Asia. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2022, 147, 669–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plangoen, P.; Udmale, P. Impacts of climate change on rainfall erosivity in the Huai Luang watershed, Thailand. Atmosphere 2017, 8, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trisurat, Y.; Eawpanich, P.; Kalliola, R. Integrating land use and climate change scenarios and models into assessment of forested watershed services in Southern Thailand. Environ. Res. 2016, 147, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Xu, Y.J.; Xiao, W.; Wang, J.; Huang, Y.; Yang, H. Climate Change Impacts on Flow and Suspended Sediment Yield in Headwaters of High-Latitude Regions—A Case Study in China’s Far Northeast. Water 2017, 9, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanapathi, T.; Thatikonda, S. Investigating the impact of climate and land-use land cover changes on hydrological predictions over the Krishna river basin under present and future scenarios. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 721, 137736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.; Phuong, T.T.B.; Duong, D.V.; Banerjee, S.; Ho, L.H. Linking Ecosystem Services through Nature-Based Solutions: A Case Study of Gia Dinh and Tao Dan Parks in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2024, 150, 05024016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.Q.; Korbee, D.; Ho, H.L.; Weger, J.; Hoa, P.T.T.; Duyen, N.T.T.; Luan, P.D.M.H.; Luu, T.T.; Thao, D.H.P.; Trang, N.T.T.; et al. Farmer adoptability for livelihood transformations in the Mekong Delta: A case in Ben Tre province. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2019, 62, 1603–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.D.; Huu, L.H.; Hoang, L.P.; Pham, T.D.; Nguyen, A.H. Sustainability of rice-based livelihoods in the upper floodplains of Vietnamese Mekong Delta: Prospects and challenges. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 243, 106495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trang, N.T.T.; Loc, H.H. Livelihood sustainability of rural households in adapting to environmental changes: An empirical analysis of ecological shrimp aquaculture model in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta. Environ. Dev. 2021, 39, 100653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosa, P.; Sukwimolseree, T. Simulation of flood protection using Hec Ras modeling: A case study of the Lam Phra Phloeng river basin. J. Appl. Res. Sci. Technol. (JARST) 2024, 23, 254752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).