3.1. Effects of Earthworm Inoculation on Plant Biomass

3.1.1. Effects of Earthworm Size on Plant Biomass

After the pot experiment, data were grouped according to earthworm size. The statistical results of plant biomass under different earthworm size treatments are presented in

Table 6. The results indicated that the Big Earthworm (BE) group exhibited higher biomass values than the Small Earthworm (SE) group. Specifically, leaf fresh weight increased by 24.7%, root fresh weight by 26.9%, root diameter by 11.8%, and root length by 22.4%.

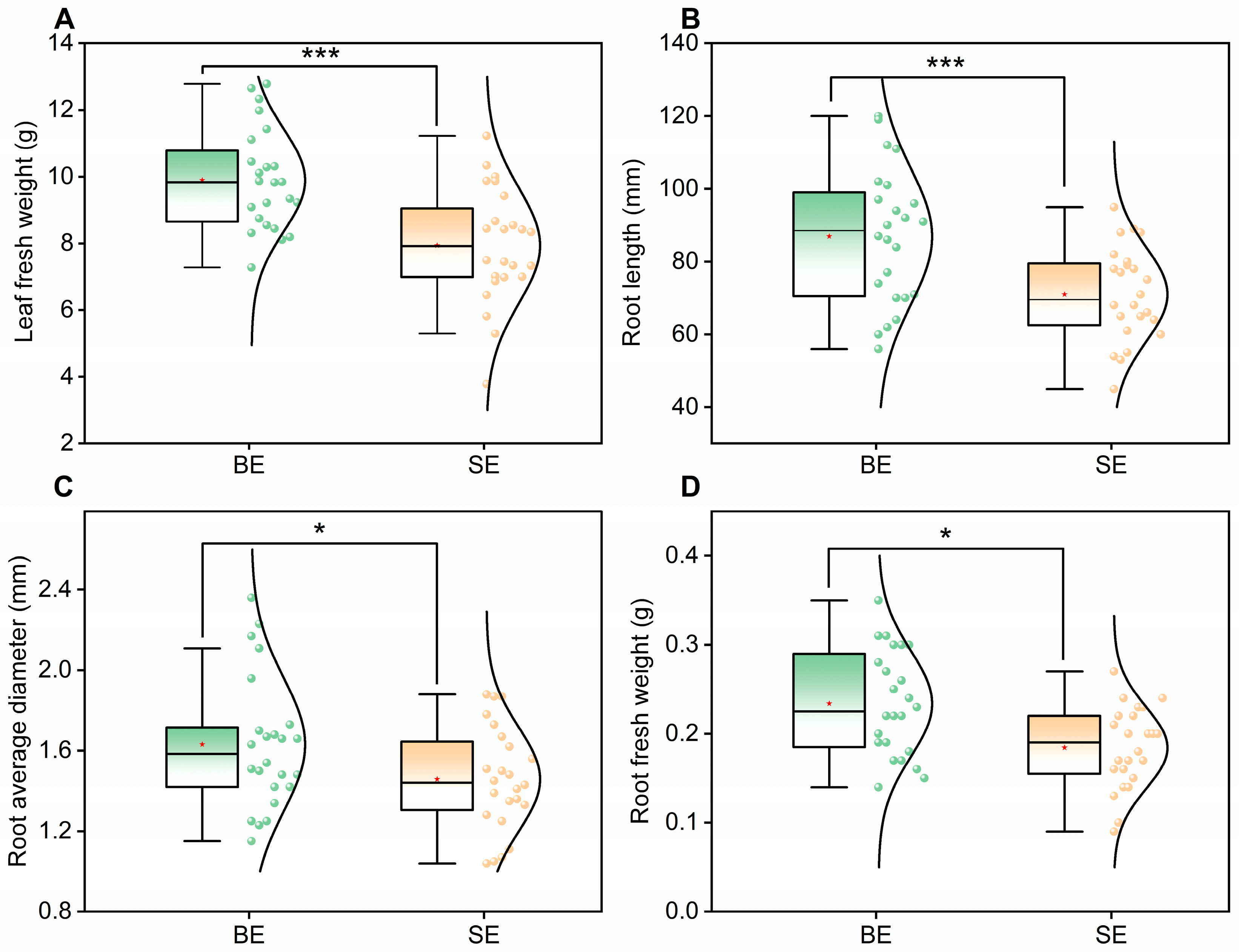

The boxplot statistical results of plant leaf fresh weight, root length, average root diameter, and root fresh weight after treatments with big earthworms (BE group) and small earthworms (SE group) are shown in

Figure 1.

For leaf fresh weight (

Figure 1A), the BE group had a significantly higher median value than the SE group (F(1,46) = 17.448,

p < 0.001). Data from the BE group were concentrated within a narrower interquartile range (IQR), with most values clustering at higher levels, whereas the SE group displayed a wider distribution toward lower values. The non-overlapping confidence intervals and highly significant differences indicate that large earthworms have a consistent positive effect on leaf biomass accumulation.

A similar trend was observed for root length (

Figure 1B): the BE group exhibited a significantly greater median than the SE group (F(1,46) = 11.588,

p < 0.001), with more uniform root growth and lower variability. For average root diameter (

Figure 1C), the BE group also outperformed the SE group (F(1,46) = 4.111, 0.001 <

p < 0.05), showing higher central tendency and less data dispersion. Likewise, root fresh weight (

Figure 1D) was significantly higher in the BE group (F(1,46) = 10.574,

p < 0.05).

Overall, the BE group consistently exhibited superior plant performance in all measured traits, suggesting that larger earthworms promote both aboveground (leaf) and belowground (root) biomass accumulation. The BE group also showed more concentrated data distributions, reflecting not only higher productivity but also greater growth stability. This can be attributed to the ability of large earthworms to construct deeper and wider burrows, improving soil aeration and accelerating organic matter decomposition, thereby enhancing nutrient availability for plant uptake. In contrast, the SE group displayed greater variability and lower biomass accumulation, likely because smaller earthworms have a limited capacity to modify soil physical and chemical properties. Consequently, large earthworms exert stronger and more stable effects on crop yield and growth uniformity.

These findings are consistent with the long-standing view of earthworms as “ecosystem engineers”, originally emphasized by Darwin and later formalized in ecological classifications of functional groups [

17]. Larger endogeic or epigeic individuals typically construct wider and deeper burrows, generate greater bioturbation, and produce more casts per unit time, thereby exerting stronger effects on soil physical structure than smaller individuals [

25]. Previous studies in temperate arable soils have shown that earthworm activity can reduce bulk density, increase macroporosity and saturated hydraulic conductivity, and facilitate root penetration along biogenic channels, ultimately enhancing shoot and root biomass of crops such as wheat and maize [

20]. Our results for

Brassica rapa L. ssp.

chinensis are in line with these observations, suggesting that the size-dependent modification of the pore network was a major driver of the improved biomass in the BE treatment.

The more concentrated data distribution in the BE group also suggests that large earthworms provided a relatively homogeneous soil environment within the pots, reducing small-scale heterogeneity in aeration and water availability. In contrast, the SE group showed greater variability and a higher frequency of low biomass values, which is likely related to the limited capacity of small earthworms to restructure soil aggregates and create persistent macropores. Although this study did not directly quantify changes in soil hydraulic properties or nutrient availability, earlier work in the same black soil region has demonstrated that Eisenia fetida can form reticulated macropore networks and improve pore connectivity under similar straw-amended conditions [

3,

40]. Taken together, these results reinforce the idea that, under black soil conditions, earthworm body size is a key determinant of their engineering effects on soil structure and, consequently, crop performance.

3.1.2. Effects of Earthworm Application Timing on Plant Biomass

To further clarify the effects of earthworm release timing on the growth performance of

Brassica rapa L. ssp.

chinensis.

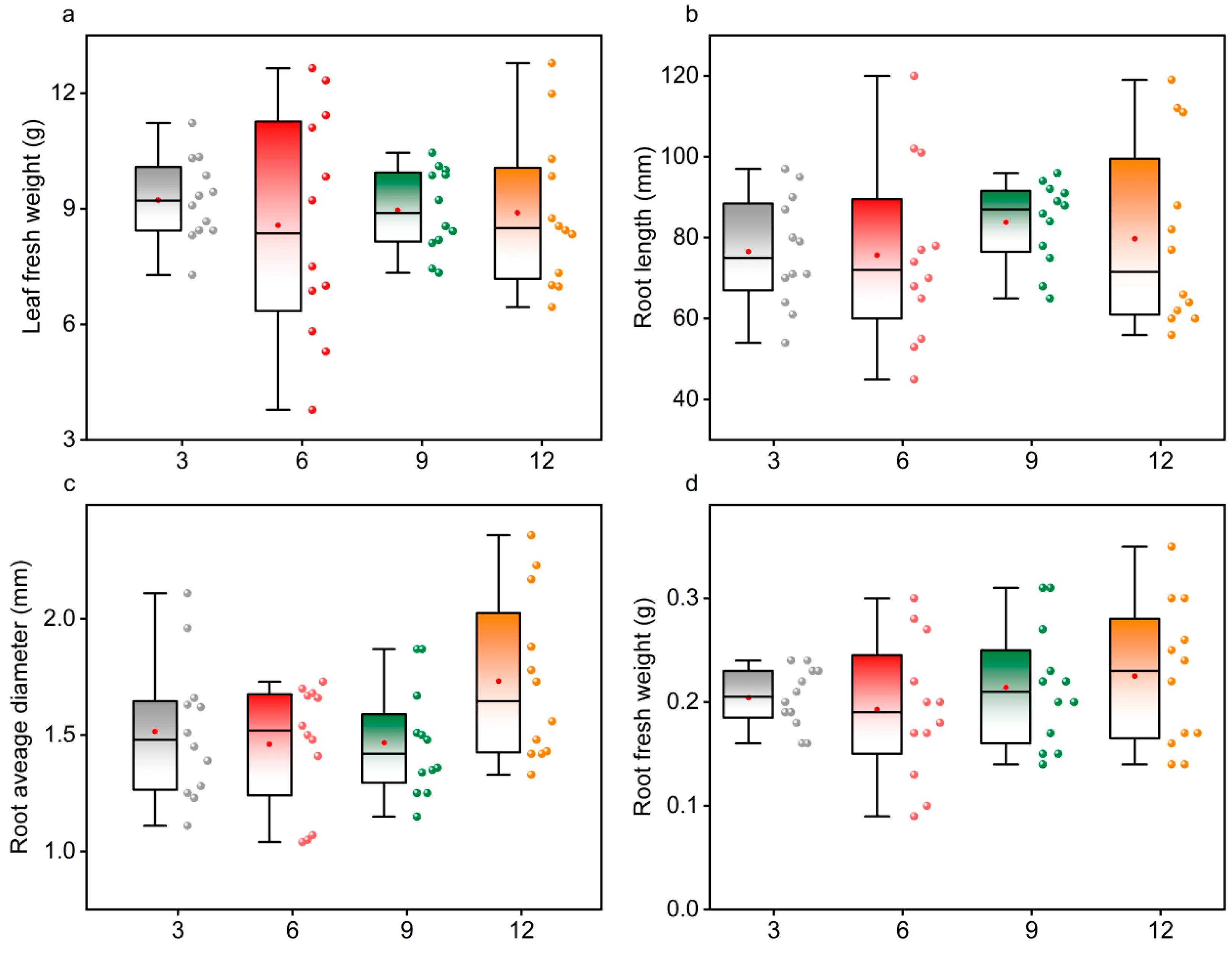

Figure 2 presents the box-and-whisker plots of leaf fresh weight, root length, average root diameter, and root fresh weight across the different treatments. These visual comparisons provide an intuitive understanding of how the timing of earthworm introduction influences above-ground and below-ground biomass accumulation, thereby revealing the optimal intervention period for maximizing plant growth promotion.

Significant differences in plant biomass were observed among treatments with different earthworm application timings. For leaf fresh weight (

Figure 2A), the differences among groups were highly significant (F(3,44) = 9.254,

p < 0.001). The sowing-stage treatment (S group) exhibited the highest leaf fresh weight, which was 36.76% higher than that of the pre-sowing treatment (PS group), 17.93% higher than that of the post-germination treatment (AG group), and 34.87% higher than that of the growth-stage treatment (GP group). Pairwise comparisons indicated that the leaf fresh weight of the S group was significantly greater than that of the PS group (

p < 0.001), GP group (

p < 0.001), and AG group (

p = 0.015).

Root length showed a similar trend (

Figure 2B). The S group exhibited the best performance among all treatments (F(3,44) = 18.28,

p < 0.001), with mean root length values 15.78%, 48.04%, and 45.12% higher than those of the AG, GP, and PS groups, respectively.

For average root diameter (

Figure 2C), the S group also outperformed the PS and AG groups (F(3,44)= 4.443,

p < 0.001), with increases of 26.60% and 22.26%, respectively. Although the mean root diameter in the S group was 9.56% higher than in the GP group, this difference was not statistically significant.

Root fresh weight followed the same pattern (

Figure 2D). The S group had significantly higher root fresh weight than all other treatments (F(3,44) = 6.755,

p < 0.001), with increases of 42.99%, 30.04%, and 41.70% compared with the PS, AG, and GP groups, respectively.

These results clearly demonstrate that earthworm application timing exerts a significant influence on plant biomass accumulation, particularly affecting both leaf and root traits. Among all treatments, sowing-stage earthworm application (S group) consistently achieved the highest values for leaf fresh weight, root length, average root diameter, and root fresh weight. This finding indicates that the sowing period represents the optimal window for maximizing the growth-promoting effects of earthworms.

Previous studies have emphasized that earthworm activity during crop establishment and early growth improves soil structure, nutrient mineralization, and rhizosphere conditions, thereby promoting root proliferation and aboveground biomass accumulation [

41]. As roots progressively occupy available pore space, structural changes occurring later in the season are generally considered to have weaker impacts on plant growth, because the potential for root system reconfiguration is reduced.

The superior performance of the S group may be attributed to the immediate improvement in soil structure following earthworm introduction at the sowing stage. Earthworm activity at this time enhances soil aeration and water-holding capacity, providing favorable conditions for root establishment and early nutrient uptake [

42,

43]. In contrast, applying earthworms after germination (AG group) or during the growth stage (GP group) was less effective. At these later stages, the already developed root system may occupy available ecological niches within the soil, thereby limiting the extent to which earthworm activity can improve soil structure or nutrient availability [

44].

Although pre-sowing application (PS group) also enhanced plant growth relative to the control, its effects were weaker than those of the S group. This may be due to the partial decline of soil improvement effects during the interval between earthworm introduction and seed germination.

In summary, earthworm application timing plays a crucial role in influencing plant growth, especially in terms of leaf and root biomass. Applying earthworms before or during sowing is most beneficial, likely because earthworm activity during these stages improves soil porosity, aeration, and moisture retention, thereby facilitating root development and nutrient absorption [

19]. In contrast, applications after germination or during later growth stages yield relatively limited effects, possibly due to competition between existing roots and earthworms for space and resources within the soil.

3.1.3. Effects of Earthworm Earthworm Inoculation Rates on Plant Biomass

To further evaluate the influence of earthworm inoculation rates on plant growth performance,

Brassica rapa L. ssp.

chinensis was cultivated under four different earthworm densities.

Figure 3 presents the box-and-whisker plots illustrating the variations in key plant biomass traits, including leaf fresh weight, root length, root average diameter, and root fresh weight. These results provide a visual comparison of how increasing earthworm density affects both above-ground and below-ground biomass accumulation.

For leaf fresh weight (

Figure 3a), slight differences were observed among treatments, with the group receiving six earthworms per pot showing marginally higher median values. However, none of these differences reached statistical significance. Root length exhibited a similar pattern (

Figure 3b): substantial overlap was observed among all treatments, and no consistent increasing or decreasing trend was detected with increasing earthworm density. For average root diameter (

Figure 3c), data variability was relatively high, and no clear separation between treatments was found. Root fresh weight followed the same trend (

Figure 3d): the interquartile ranges overlapped substantially, and data distributions were scattered across all treatments.

In summary, variations in earthworm inoculation density did not result in significant or systematic changes in aboveground or belowground biomass accumulation. The absence of significant differences among groups suggests that, within the range tested in this experiment, increasing earthworm density did not measurably promote plant growth.

Several factors may explain these results. First, the experiment was conducted in pots with a soil surface area of 256 cm

2. The applied earthworm densities—equivalent to 117, 234, 351, and 468 individuals per square meter—were considerably higher than those typically found under field conditions [

44]. Previous studies have reported that under conventional tillage systems, the average earthworm density is approximately 51 individuals per square meter, whereas under crop rotation systems, the density can reach about 124 individuals per square meter [

45]. Moreover, even during the less active autumn season, the earthworm density in the 0–10 cm surface soil layer was observed to be around 57.41 individuals per square meter [

46]. Evidently, the densities used in this experiment were several times higher than those occurring naturally in agricultural soils. It is important to recognize that while moderate earthworm densities can enhance soil aeration, water retention, and nutrient cycling, excessively high densities may negatively impact plant growth by causing excessive soil disturbance, root damage, and nutrient imbalance [

47]. Intensive burrowing and casting in a limited space may lead to excessive fragmentation of aggregates, localized compaction around burrow walls, or rapid turnover of macropores, all of which can destabilize the pore network and disturb root–soil contact. The results observed in this study may, therefore, reflect the potential detrimental effects of very high earthworm densities, which are uncommon in natural or agricultural settings. These factors highlight the importance of balancing earthworm density for optimizing their ecological benefits without compromising plant growth. Future studies should consider exploring more ecologically relevant density levels to fully understand the thresholds beyond which earthworm populations may begin to have a negative effect on plant performance. At such high densities, excessive earthworm activity in all treatments may have caused similar degrees of soil disturbance, thereby minimizing relative differences in soil structure improvement and nutrient dynamics among treatments. Second, the limited volume of the pots restricted earthworm movement and burrow formation, preventing full expression of their ecological functions. Under natural field conditions, earthworm activity enhances soil aeration, water retention, and nutrient mineralization efficiency. However, under potted conditions, reduced spatial heterogeneity likely constrained these beneficial effects. Consequently, even at the highest density, plant biomass accumulation did not show measurable advantages compared with lower-density treatments.

Overall, under pot conditions, earthworm inoculation density was not a primary determinant of plant biomass accumulation. The confined experimental environment may have masked potential density-dependent effects that are more likely to emerge under field conditions. Future studies should employ larger-scale soil systems with ecologically relevant density gradients to more accurately capture the potential influence of earthworm abundance on plant growth.

3.2. Gray Correlation Analysis Results

To further quantify the relative importance of each factor affecting the growth performance of

Brassica rapa L. ssp.

chinensis, grey relational analysis (GRA) was conducted to evaluate the associations between earthworm-related variables and plant biomass traits. The resulting average grey relational grade (GRG) values for each factor and treatment level are illustrated in

Figure 4. This analysis provides an integrative perspective on how earthworm size, release period, and number of releases influence key plant growth indicators, including leaf fresh weight, root length, root average diameter, and root fresh weight.

Based on the GRG values presented in

Figure 4, the degree of influence of different levels of the three major factors—earthworm size (ES), earthworm release period (ERP), and number of releases (NR)—on the biomass traits of

Brassica rapa L. ssp.

chinensis was determined. The GRG values across different factor levels exhibited a broadly consistent trend, suggesting that the effects of each variable were uniform in direction and magnitude.

Among the three factors, earthworm size showed a stable and relatively high correlation with all biomass indices, with GRG values of approximately 0.7 for both large and small earthworms. This indicates that earthworm size exerts a strong and consistent effect on plant growth, influencing both aboveground (leaf fresh weight) and belowground (root length, root diameter, and root fresh weight) parameters in a similar manner.

In contrast, the GRG values associated with the earthworm release period varied considerably across treatments, demonstrating its greater influence on plant growth dynamics. As shown by the yellow line in

Figure 4a, the GRG values for leaf fresh weight were 0.51 (PS), 0.55 (S), 0.76 (AG), and 0.40 (GP). The after-germination (AG) group exhibited the highest GRG, followed by the pre-sowing (PS) and sowing (S) groups, while the growing period (GP) group had the lowest correlation. When combined with the results from

Figure 2A, it can be inferred that the AG treatment had the strongest negative impact on leaf biomass, while the S treatment—with a moderately high GRG—was positively correlated with enhanced leaf growth, confirming its promoting effect.

A similar trend was observed for root length (

Figure 4b). The GRG values for the AG and S groups were 0.58 and 0.55, respectively, while those for the GP and PS groups were 0.40 and 0.42. The AG group again showed the strongest correlation but negatively influenced root elongation, whereas the S group demonstrated a strong and positive association, leading to significantly longer roots. This suggests that synchronization between earthworm activity and root establishment is crucial: when earthworms are present during sowing, the burrow network formed in parallel with root exploration offers low-resistance pathways and improved aeration for root penetration. In contrast, when earthworms are introduced after germination, the newly formed burrows may partially replace rather than complement the root exploration front, resulting in shorter and less extensively distributed roots.

For root average diameter (

Figure 4c), the AG and S groups also exhibited relatively high GRG values (0.65 and 0.60, respectively), indicating strong correlations with root morphology. The AG group’s high GRG was associated with a reduction in root thickness, while the S group displayed a positive relationship, significantly promoting root expansion. In contrast, the PS (0.48) and GP (0.43) groups showed weak associations with this trait. These results imply that earthworm activity during the early establishment phase not only affects root length but also modifies root architectural traits, including radial growth. Increased root diameter in the S group is likely related to improved nutrient availability and more stable water supply in earthworm burrows, which favors the development of thicker, transport-efficient roots. Conversely, the thinner roots observed in the AG group may reflect a stress response to unstable soil physical conditions and competition for limited pore space.

A comparable pattern was observed in root fresh weight (

Figure 4d). The AG group exhibited the highest correlation (GRG = 0.70), followed by PS (0.55) and S (0.53). However, when combined with

Figure 2D, it becomes evident that the AG group’s high GRG corresponded to a negative effect—reducing root biomass—whereas the S group promoted root development with a moderate-to-high GRG value. Together with the other root traits, this indicates that earthworm introduction after germination can strongly reshape root growth, but in an unfavorable direction under the present experimental conditions.

Overall, the GRA results demonstrate that earthworm size and release period are the dominant factors influencing the biomass traits of Brassica rapa L. ssp. chinensis, while the number of releases exerts a minimal effect. More importantly, the impact of the release period can be either positive or negative depending on timing. The sowing (S) treatment showed a strong positive correlation with biomass accumulation in both leaves and roots, whereas the after-germination (AG) treatment, despite its high GRG value, negatively affected plant growth. This highlights the necessity of jointly interpreting GRG values with actual trait responses: high GRG indicates that a factor level strongly “controls” the outcome, but agronomic benefit depends on whether that control enhances or suppresses growth. The consistency of multi-trait results confirms that introducing earthworms during the sowing period is the optimal strategy for maximizing biomass accumulation and improving plant growth performance. From an application perspective, these findings suggest that earthworm-based soil management should prioritize aligning earthworm activity with the crop establishment stage, rather than simply increasing inoculation frequency or density at later growth stages.

3.3. Analysis of Leaf Growth Rate

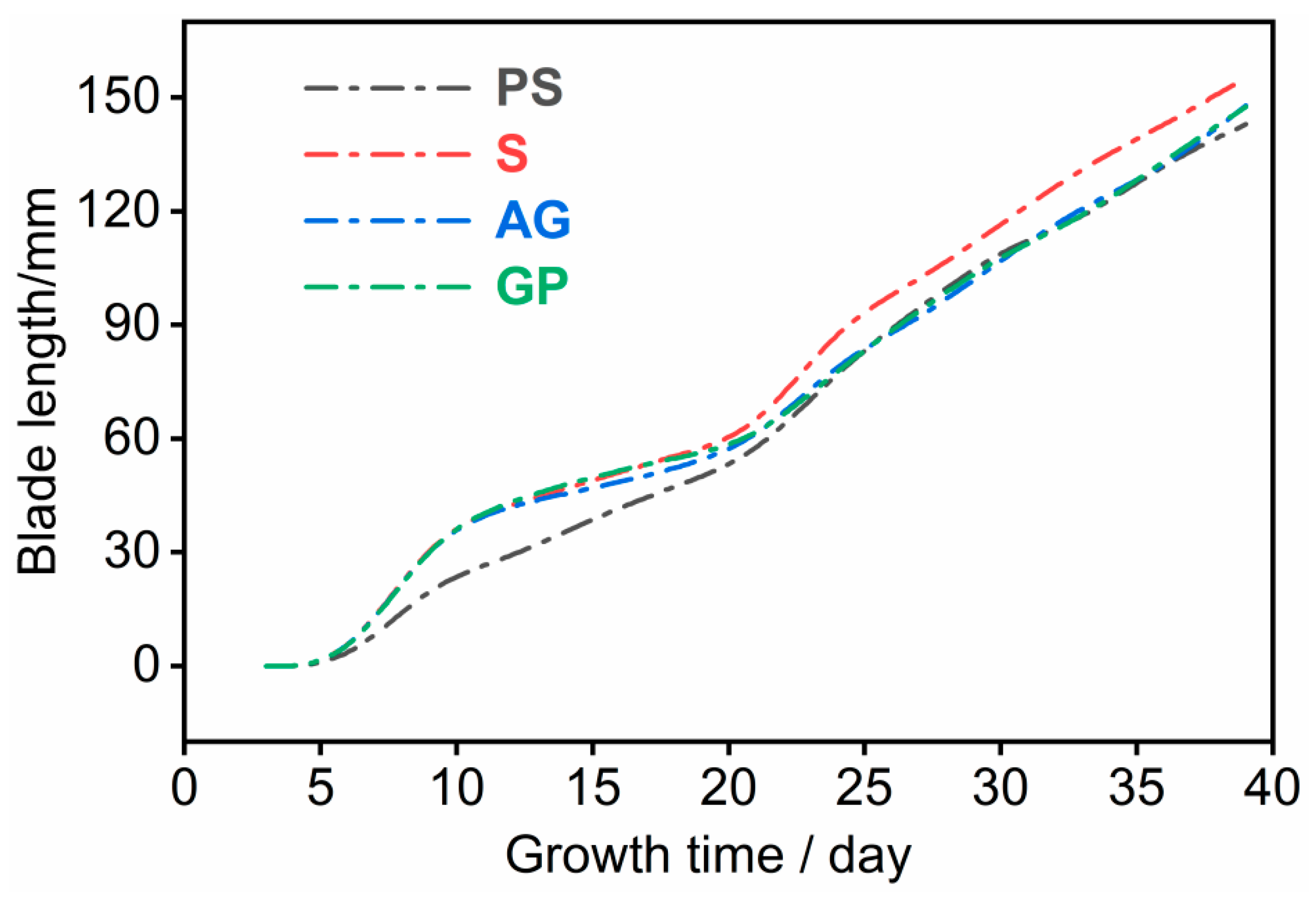

To further investigate the temporal dynamics of plant growth under different earthworm release periods, the leaf length growth curves of

Brassica rapa L. ssp.

Chinensis were analyzed over the 40-day cultivation period. The growth trajectories under the four treatments—pre-sowing (PS), sowing (S), after-germination (AG), and growing period (GP)—are presented in

Figure 5. This analysis aimed to clarify how the timing of earthworm introduction influences the continuous growth process of

Brassica rapa L. ssp.

chinensis from early establishment to maturity.

As shown in

Figure 5, the leaf growth rates of

Brassica rapa L. ssp.

chinensis exhibited similar overall trends across the four treatments, though their magnitudes varied considerably. During the early growth stage (0–10 days), the PS group, in which earthworms were introduced before sowing, displayed a markedly lower leaf length growth rate than the other three groups. This suggests that early earthworm introduction may have disrupted the initial soil–seed interaction, delaying seedling establishment. A likely explanation is that pre-sowing earthworm activity generated excessive macropores in the topsoil, which enhanced water infiltration but reduced surface water retention. As a result, the young roots of

Brassica rapa L. ssp.

chinensis, which remain shallow during the early stage, were unable to access sufficient soil moisture, thus slowing early growth.

Between 10 and 20 days of growth, the leaf elongation rate of all treatments slowed down. This period corresponds to the vegetative expansion phase of

Brassica rapa L. ssp.

chinensis, during which photosynthetic resources are mainly allocated to leaf broadening and canopy expansion rather than longitudinal growth, thereby ensuring optimal light interception for subsequent development [

48].

During the 20–25 days period, both the S and PS groups showed a noticeable rebound in leaf elongation rate compared with their earlier stages and with the AG and GP groups. This increase is likely attributable to the progressive development of root systems that had by then reached deeper soil layers. In these groups, earthworms had already formed interconnected macropore networks that enhanced soil aeration, drainage, and nutrient mobility. Such favorable soil physical conditions promoted root proliferation and nutrient absorption, thereby accelerating leaf elongation during this growth phase [

49].

From 25 to 40 days, the leaf growth rate stabilized, maintaining the level observed during the previous phase. Notably, the leaf length of plants in the S group remained consistently higher—by approximately 10 cm—than that of plants in the other three treatments. This result demonstrates that introducing earthworms at the sowing stage provides a continuous advantage throughout the plant’s later growth stages, facilitating sustained leaf elongation and greater plant height.

The S group maintained its growth advantage throughout the late growth stage, indicating that earthworm activity during this period created optimal soil aeration and moisture conditions for root respiration and nutrient uptake. These favorable conditions further enhanced metabolic efficiency and sustained vegetative growth. In contrast, overly early (PS) or delayed (AG and GP) earthworm introduction failed to synchronize with root establishment, leading to suboptimal soil–plant interactions and restricted growth performance.

Overall, the growth curve analysis confirms that the timing of earthworm introduction plays a decisive role in regulating the growth dynamics of Brassica rapa L. ssp. chinensis. Introducing earthworms during the sowing period represents the optimal strategy, as it synchronizes soil structural improvement with the critical root establishment phase, thereby maximizing water and nutrient availability and promoting continuous plant development.

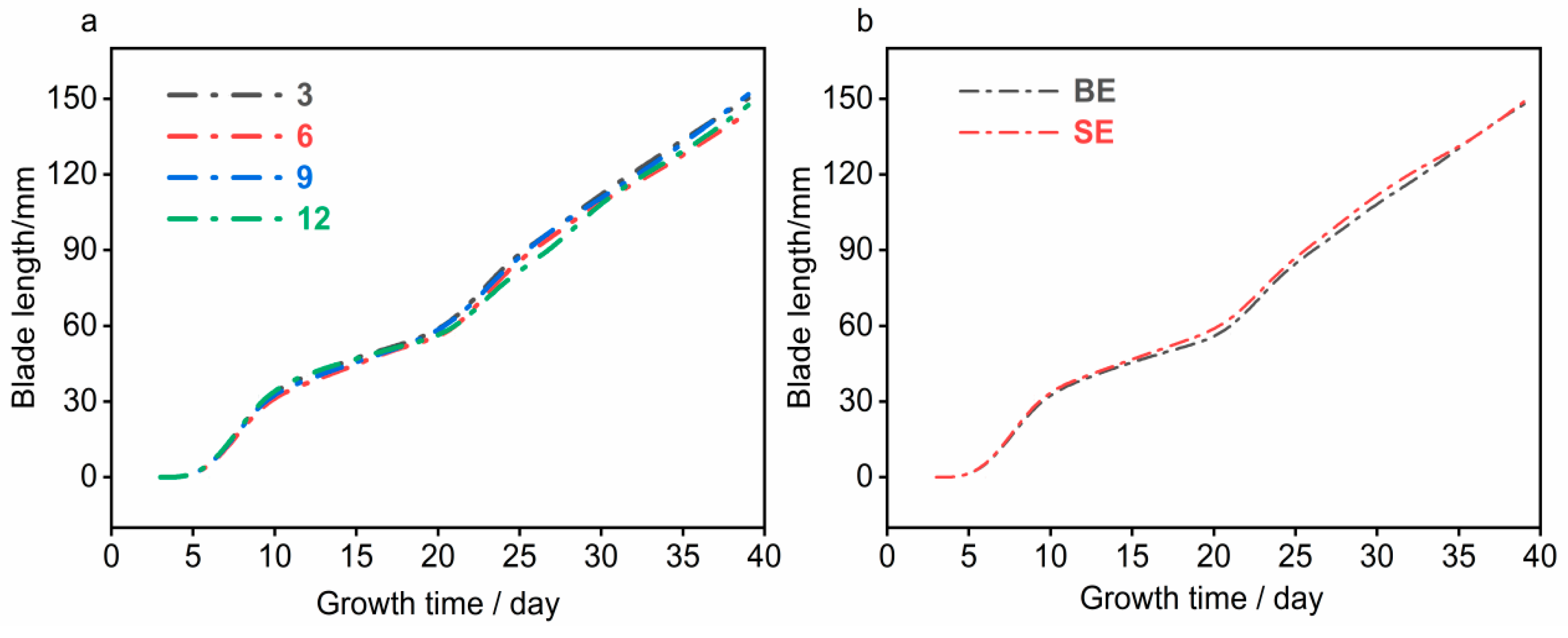

By comparing the leaf length growth rates of

Brassica rapa L. ssp.

chinensis under different earthworm introduction densities (as shown in

Figure 6), it was observed that the growth curves of all groups were nearly identical with a high degree of overlap, showing similar changes in growth rate. Several plausible reasons for this phenomenon are proposed:

First, this experiment adopted a pot culture system with a cross-sectional area of 256 cm2, and the selected earthworm density gradients were 117 ind./m2, 234 ind./m2, 351 ind./m2, and 468 ind./m2. This density gradient may have been excessively high, resulting in minimal differences in soil structure modifications caused by earthworm activity. Additionally, the variations in soil structure may have had little differential impact on improving crop growth rates, making it impossible to significantly distinguish the leaf growth rates of Brassica rapa L. ssp. chinensis among different density treatments.

Second, under high-density conditions, the disturbance of soil structure by earthworms tends to reach saturation. As a result, the differences in soil structure improvement among different treatments were negligible, failing to produce distinguishable differences in growth performance.

Third, the pot environment restricted the activity area and space of earthworms, preventing them from fully moving and interacting within the soil. Even in groups with higher earthworm densities, the modification of soil structure did not reach the level observed under natural conditions. This further contributed to the lack of significant differences in leaf growth rates of Brassica rapa L. ssp. chinensis among different density groups.

Overall, under the limited conditions of pot culture, the effects of earthworm introduction density and timing on the leaf growth rate of Brassica rapa L. ssp. chinensis were limited. However, this does not imply that differences in earthworm density would not affect crop growth in natural field-like environments. This aspect requires further verification through larger-scale and longer-duration experiments.

3.4. CT Image Analysis

Based on the results of previous significance analysis, four samples (T

3, T

4, T

15, and T

16) were selected for CT three-dimensional (3D) scanning. These four groups exhibited significant differences and representativeness in the orthogonal design: T

3 and T

4 were the treatment groups with 6 and 12 large earthworms introduced at the sowing stage, respectively, representing the optimal combinations of earthworm introduction time and size; T

15 and T

16 were the treatment groups with 6 and 12 small earthworms introduced at the growth period, respectively, representing the combinations with relatively poor growth performance. By comparing these two types of typical treatments, the differences in the effects of earthworm size and introduction time on soil structure could be highlighted under the same introduction number, thereby revealing the mechanism of earthworms in improving soil pore structure more intuitively [

50].

Figure 7 presents the 3D visualization results of soil pore structures under different treatments, including (a) the Pore Network Model (PNM), (b) the Ball-and-Stick Model, and (c) the Pore Skeleton Diagram. As shown in

Figure 7a, the number of pores and their connectivity in T

3 and T

4 were markedly superior to those in T

15 and T

16. The pore networks in T

3 and T

4 were well developed and uniformly distributed, indicating that the introduction of large earthworms at the sowing stage effectively improved the soil structure. The Ball-and-Stick Model (

Figure 7b) further revealed the relationships between pore nodes and throats: T

3 and T

4 displayed a higher density of interconnected pore spheres, whereas T

15 and T

16 exhibited fewer pores with weaker linkages. The Pore Skeleton Diagram (

Figure 7c) confirmed these observations, showing that T

3 and T

4 possessed more complex topological frameworks and higher degrees of connectivity. Together, these results demonstrate that introducing large earthworms at the sowing stage significantly enhances soil porosity and structural complexity.

Quantitative 3D porosity results are summarized in

Table 7. Overall, the pore distribution characteristics of T

3 and T

4 were significantly superior to those of T

15 and T

16. Among all treatments, T

3 exhibited the highest 3D porosity (0.1174), nearly 98 times greater than that of T

16. Both the number of marked voxels and mask voxels in T

3 were substantially higher than in T

15 and T

16, indicating a well-developed pore system. Although the pore volume fraction of T

4 was slightly lower than that of T

3, its mask volume was the highest among all groups, suggesting that this treatment promoted enhanced pore connectivity and spatial continuity. These findings confirm that the T

3 and T

4 treatments not only increased the number of soil pores but also optimized their spatial configuration, thereby improving pathways for water and air transmission [

41]. Conversely, T

15 and T

16 exhibited significantly lower pore volume fractions and fewer marked voxels, indicating that their respective treatments had limited effects on soil pore development.

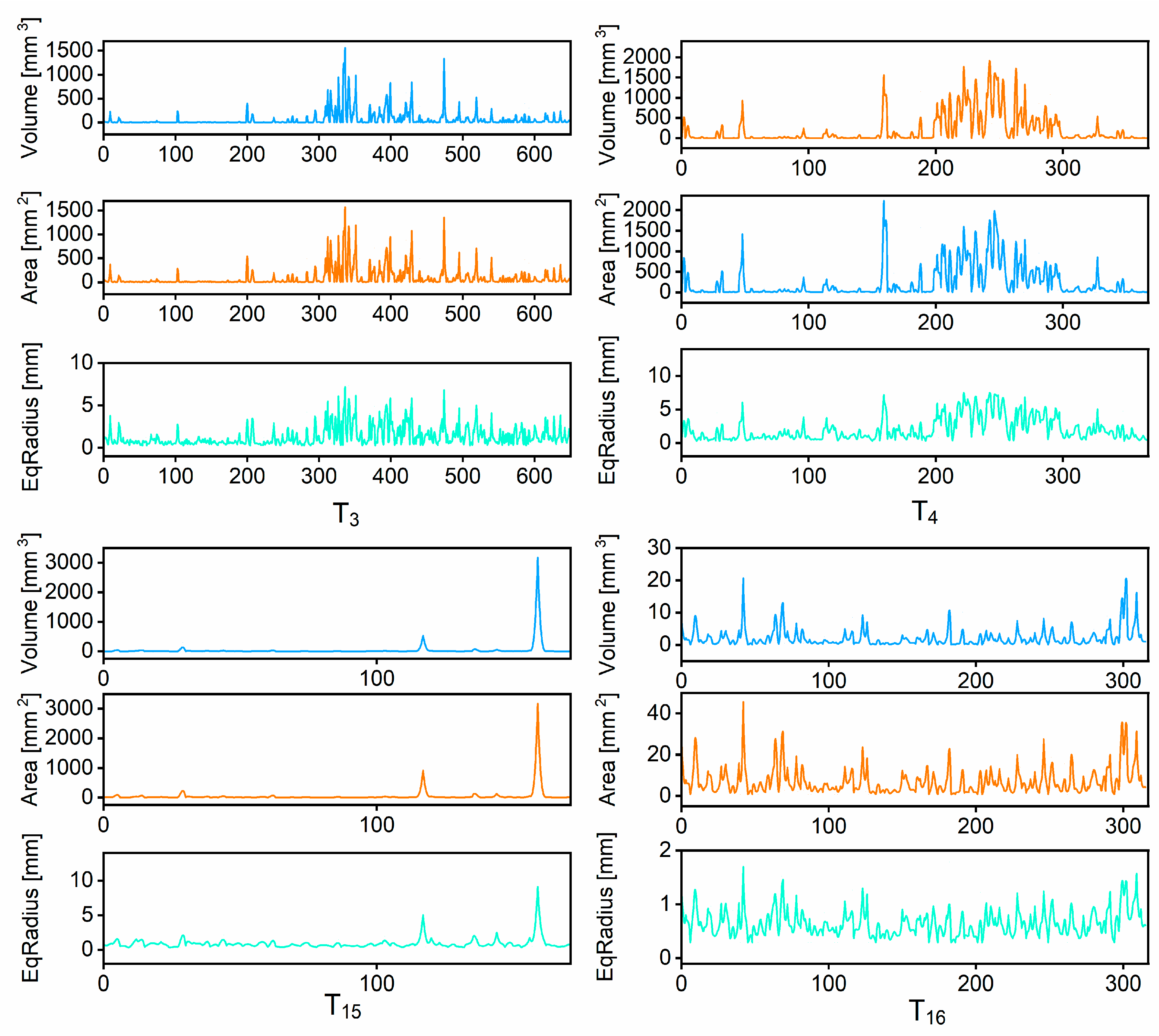

Figure 8 further illustrates the distributions of pore volume, pore surface area, and equivalent radius across the four treatments. As shown in

Figure 8, the pore volume and surface area curves for T

3 and T

4 displayed greater fluctuations and wider distribution ranges, reflecting the existence of numerous large and morphologically complex pores within the soil matrix [

51]. In particular, the maximum pore volume in T

3 reached approximately 1500 mm

3, while the corresponding peak pore surface area exceeded 1500 mm

2. In contrast, the curves of T

15 and T

16 were relatively flat, with low and narrowly distributed peaks, indicating limited pore formation and underdeveloped pore networks. The equivalent radius distribution further supported these findings: T

3 and T

4 exhibited broader and more continuous pore size spectra, whereas T

15 and T

16 were confined to small-radius pores. This pattern confirms that the latter treatments did not substantially modify the soil pore architecture [

52].

In summary, the CT 3D reconstruction results revealed pronounced differences in the effects of earthworm size and release timing on soil pore structure improvement. The introduction of large earthworms at the sowing stage (T3 and T4) markedly enhanced soil porosity and pore network complexity, characterized by abundant, well-connected, and evenly distributed macropores with wide ranges of pore volumes and surface areas. Such structural optimization improves soil aeration, enhances water retention, and creates a more favorable environment for root growth and nutrient exchange. In contrast, introducing small earthworms during the growing period (T15 and T16) had limited influence on soil structure, resulting in lower porosity, reduced connectivity, and a pore size distribution dominated by small pores. These findings highlight that both earthworm size and release timing are critical factors in optimizing the soil physical environment for sustainable crop production.

3.5. Limitations and Outlook

Although the present study provides clear evidence that earthworm size and introduction timing significantly influence both the biomass accumulation of Brassica rapa L. ssp. chinensis and the improvement of black soil structure, several limitations related to the pot experiment design should be acknowledged.

First, the confined pot environment inherently restricts the natural burrowing and dispersal behaviors of earthworms, limiting the formation of large and continuous biopores that typically occur in field soils. This spatial constraint may have reduced the expression of earthworm ecological functions such as vertical mixing, deep soil ventilation, and nutrient redistribution. Consequently, the soil structure improvement and plant growth effects observed under pot conditions might underestimate the potential impact under actual field environments.

Second, the relatively high earthworm densities used in this study, although suitable for small-scale controlled experiments, may not fully reflect the population dynamics or equilibrium densities found in natural agroecosystems. Overcrowding in a limited soil volume could lead to overlapping activity zones and competition among individuals, thereby weakening the gradient effects of introduction density and potentially masking density-dependent responses.

Third, environmental parameters such as temperature, moisture dynamics, and microbial community interactions are relatively homogeneous in a greenhouse pot system compared with open-field conditions. These controlled factors, while ensuring experimental repeatability, may reduce ecological realism. In the field, variations in microclimate, soil compaction, and organic matter distribution can significantly alter earthworm behavior and consequently affect soil structural outcomes.

Therefore, although the findings of this study provide important mechanistic insights and quantitative evidence for optimizing earthworm introduction strategies, caution should be exercised when extrapolating these results to large-scale field conditions. Future studies should include long-term field trials across multiple soil types and crop species to validate the applicability of the identified optimal strategy—introducing large earthworms during the sowing stage—under diverse agricultural settings. Combining in-situ monitoring of earthworm activity with high-resolution imaging and soil physical measurements will be essential for developing a more comprehensive understanding of earthworm–soil–plant interactions in natural environments.