Beyond Conventional Fertilizer: Tannin–Chlorella vulgaris Blends as Biostimulants for Growth and Yield Enhancement of Strawberry (Fragaria x ananassa Duch)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Production and Test of the Alternative Fertilizers (Tannins and C. vulgaris Extracts)

2.1.1. Tannin Water Extract and Phytotoxicity Test

2.1.2. Chlorella vulgaris Growth and Extract Preparation

2.2. Plant Material and Setup of Experiment 1 and 2

2.2.1. Experimental Setup of Experiment 1: Tannin Concentration Determination

2.2.2. Experimental Setup of Experiment 2: Effects of Tannin and C. vulgaris Microalgae on Plant Performance and Growth

- CNT = Control (irrigation with water);

- T = tannin water extract irrigation treatment [54% T.E.];

- C1 = C. vulgaris algae spray treatment [50× dilution];

- C2 = C. vulgaris algae spray treatment [100× dilution];

- T+C1 = tannin water extract [54% T.E.] irrigation + C. vulgaris algae [50× dilution] spray treatment.

2.3. Biometric Parameters: Plant Growth

2.4. Leaf Gas Exchange and Leaf Pigments Measurements

2.5. Chlorophyll a Fluorescence Measurement

2.6. Mineral Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Phytotoxicity Test on the Tannin Water Extract Produced via Hydrodynamic Cavitation

3.2. Experiment 1: Tannin Treatments at Three Different Concentrations on Strawberry Plants

3.3. Experiment 2: Effect of Tannin and Chlorella Treatments on Strawberry Plants

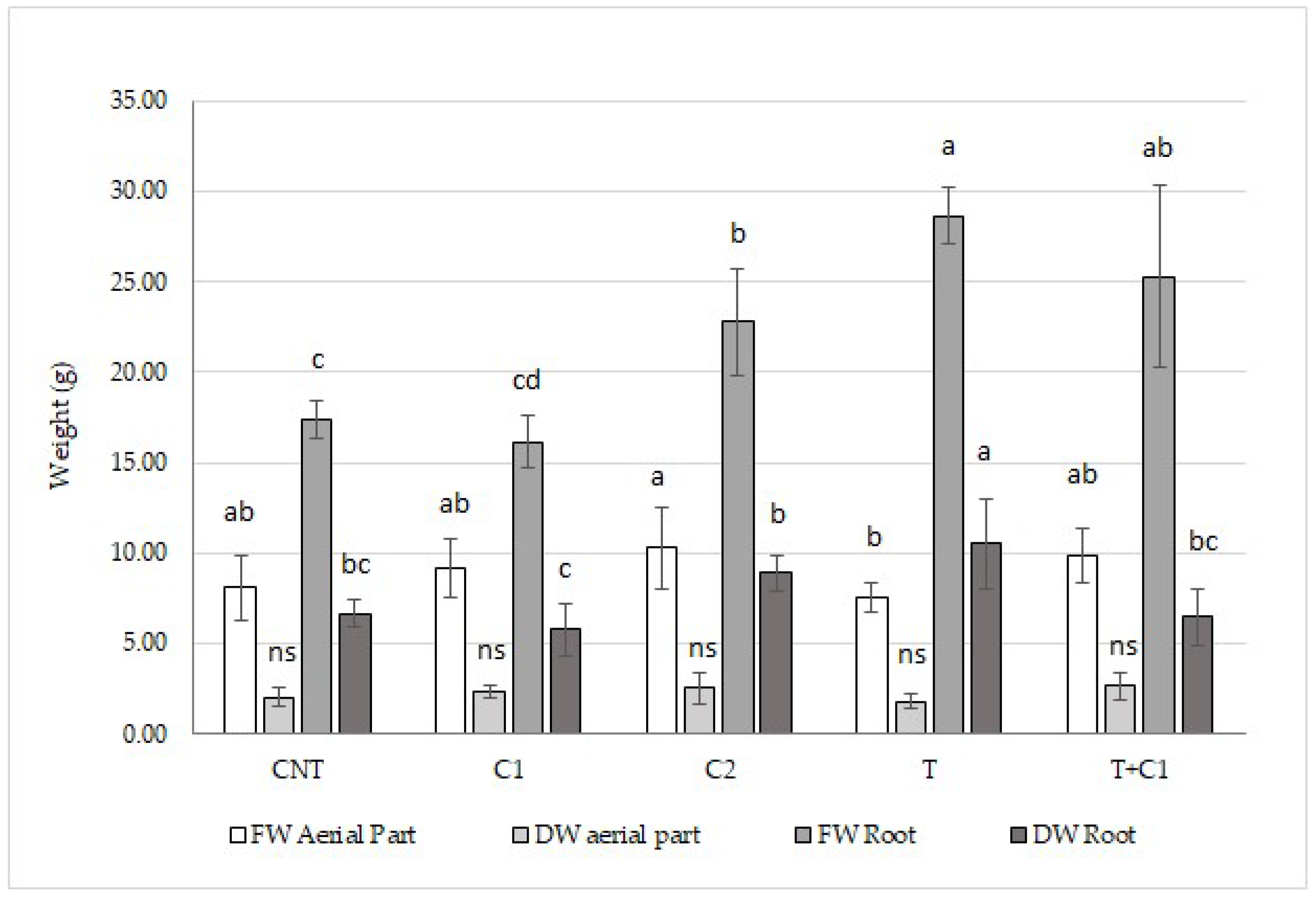

3.3.1. Biomass

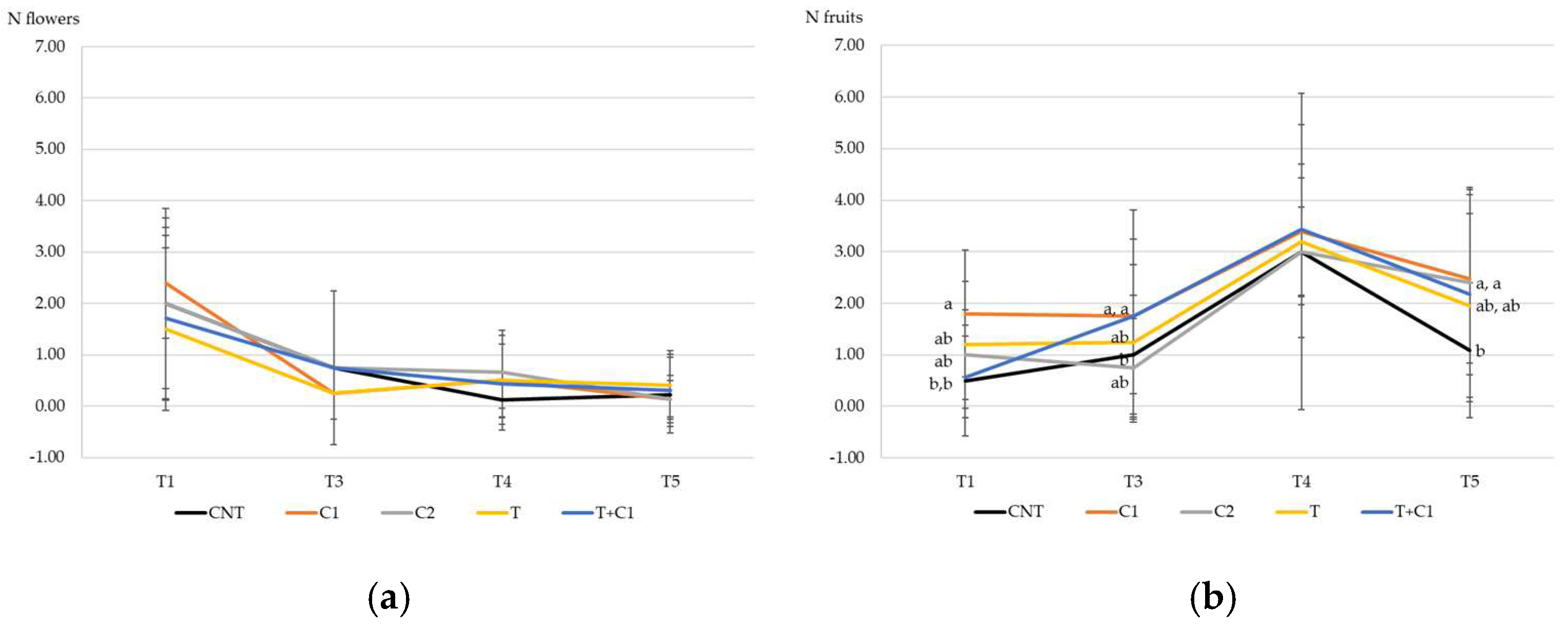

3.3.2. Production of Flowers and Fruits

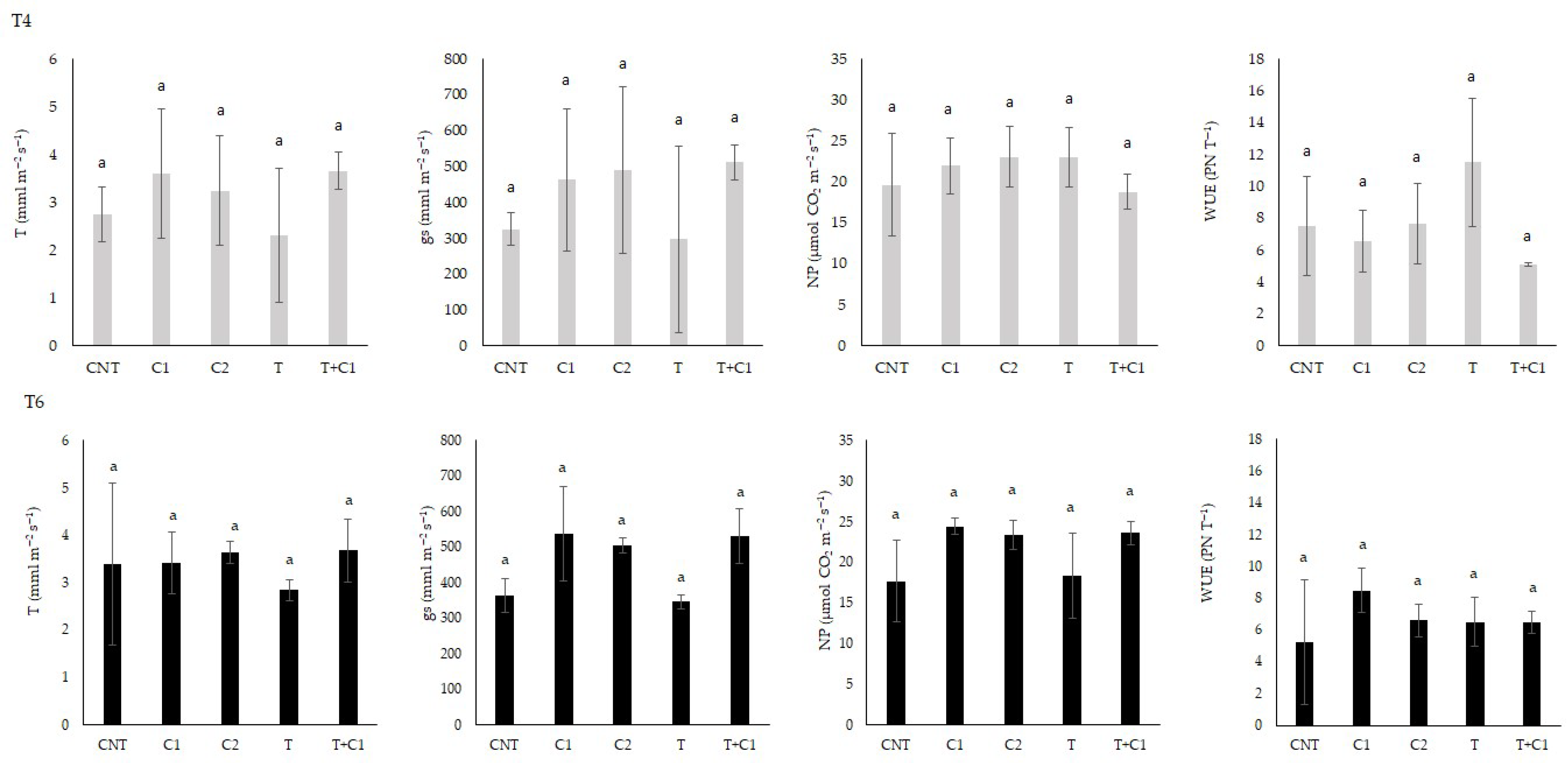

3.3.3. Leaf Gas Exchange and Leaf Pigments

3.3.4. Chlorophyll Fluorescence Measurements

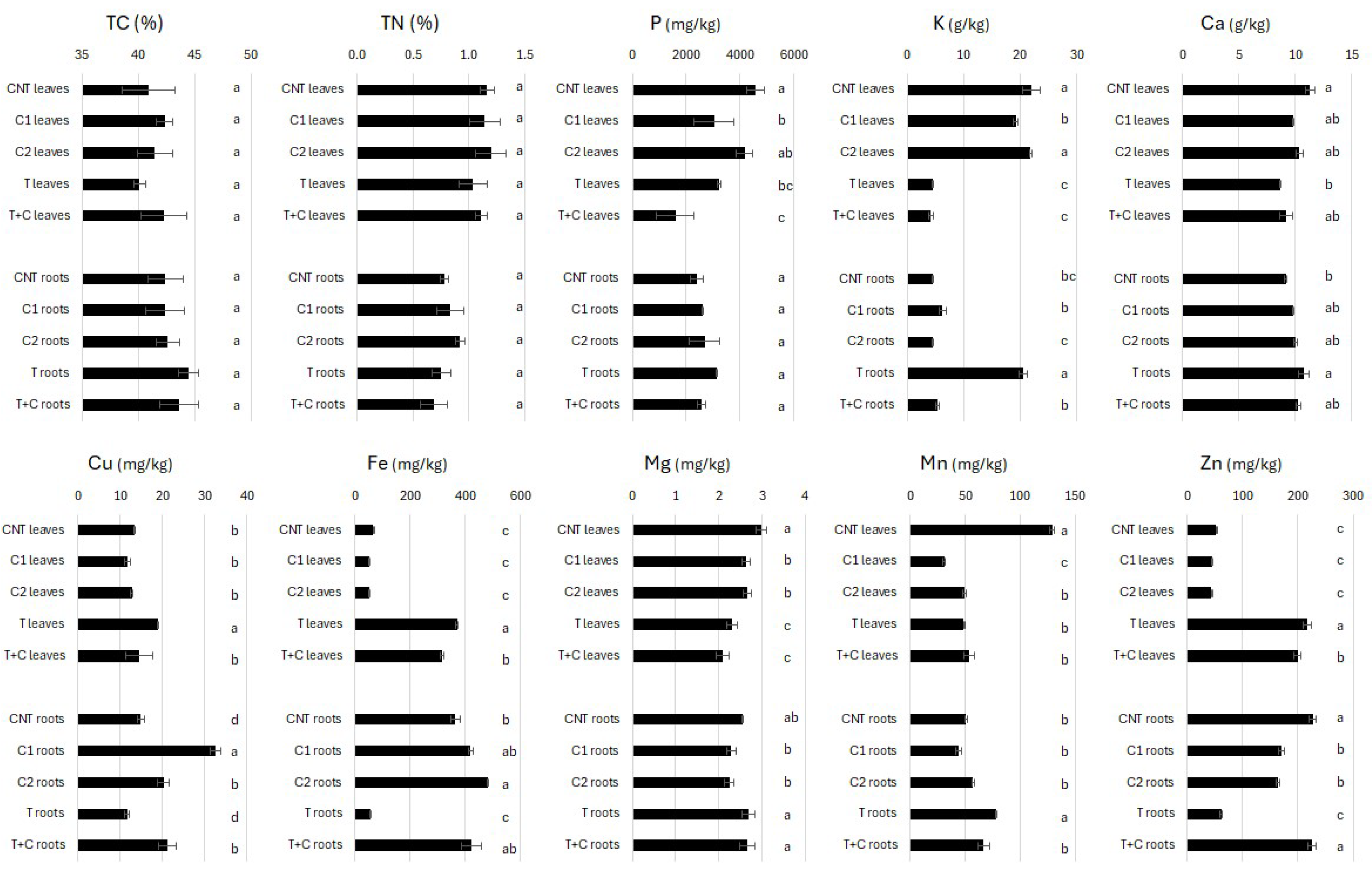

3.3.5. Mineral Composition

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tulipani, S.; Romandini, S.; Suarez, J.M.A.; Capocasa, F.; Mezzetti, B.; Battino, M.; Busco, F.; Bamonti, F.; Novembrino, C. Folate Content in Different Strawberry Genotypes and Folate Status in Healthy Subjects after Strawberry Consumption. Biofactors 2008, 34, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newerli-Guz, J.; Śmiechowska, M.; Drzewiecka, A.; Tylingo, R. Bioactive Ingredients with Health-Promoting Properties of Strawberry Fruit (Fragaria x ananassa Duchesne). Molecules 2023, 28, 2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Statistical Database. Available online: https://www.fao.org/statistics/en (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Maas, J. Strawberry Diseases and Pests-Progress and Problems. In Proceedings of the VII International Strawberry Symposium, Beijing, China, 18 February 2012; pp. 133–142. [Google Scholar]

- Trejo-Téllez, L.I.; Gómez-Merino, F.C. Nutrient Management in Strawberry: Effects on Yield, Quality and Plant Health. In Strawberries: Cultivation, Antioxidant Properties and Health Benefits; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 239–267. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, J.P.T. Plant Growth Regulators in Horticulture: Practices and Perspectives. Biotecnol. Veg. 2019, 19, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur, Y.; Chandel, J.; Verma, P. Effect of Plant Growth Regulators on Growth, Yield and Fruit Quality of Strawberry (Fragaria x ananassa Duch.) under Protected Conditions. J. Appl. Nat. Sci. 2017, 9, 1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarpuz-Bozdogan, N.; Atakan, E.; Bozdogan, A.M.; Yilmaz, H.; Daglioglu, N.; Erdem, T.; Kafkas, E. Effect of Different Pesticide Application Methods on Spray Deposits, Residues and Biological Efficacy on Strawberries. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2011, 6, 660–670. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, P.K.; Sachan, R.; Dwivedi, D.K. Ecological Consequences: Understanding the Effects of Agricultural Pollution on Ecosystem, Wildlife, and Biodiversity. In A Comprehensive Exploration of Soil, Water, and Air Pollution in Agriculture; BFC Publications: Uttar Pradesh, India, 2024; Volume 139. [Google Scholar]

- Yanardağ, A.B. Damage to Soil and Environment Caused by Excessive Fertilizer Use. In Agriculture, Forestry and Aquaculture Sciences; Serüven Publishing: Ankara, Turkey, 2024; pp. 203–213. [Google Scholar]

- Baldi, E.; Nestby, R.; Raynal-Lacroix, C.; Lieten, P.; Salo, T.; Pivot, D.; Lucchi, P.; Baruzzi, G.; Faedi, W.; Tagliavini, M. Uptake and Partitioning of Major Nutrients by Strawberry Plants. In Euro Berry Symposium-COST-Action 836 Final Workshop; ISHS: Ancona, Italy, 2003; pp. 197–200. [Google Scholar]

- Du Jardin, P. Plant Biostimulants: Definition, Concept, Main Categories and Regulation. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 196, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2019/1009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 June 2019 Laying down Rules on the Making Available on the Market of EU Fertilising Products and Amending Regulations (EC) No 1069/2009 and (EC) No 1107/2009 and Repealing Regulation (EC) No 2003/2003. 2019. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2019/1009/oj (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Sellami, M.H.; Di Mola, I.; Mori, M. Evaluating Wheat Response to Biostimulants: A 25-Year Review of Field-Based Research (2000–2024). Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1543981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campobenedetto, C.; Mannino, G.; Beekwilder, J.; Contartese, V.; Karlova, R.; Bertea, C.M. The Application of a Biostimulant Based on Tannins Affects Root Architecture and Improves Tolerance to Salinity in Tomato Plants. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubkina, N. Microalgae in Agricultural Crop Production. Italus Hortus 2022, 29, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.K.; Islam, M.N.; Faruk, M.O.; Ashaduzzaman, M.; Dungani, R. Review on Tannins: Extraction Processes, Applications and Possibilities. South Afr. J. Bot. 2020, 135, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisciotta, A.; Ciriminna, R.; Planeta, D.; Miccichè, D.; Barone, E.; Di Lorenzo, R.; Puccio, S.; Turano, L.; Scurria, A.; Albanese, L.; et al. HyTan Chestnut Tannin: An Effective Biostimulant for the Nursery Production of High-Quality Grapevine Planting Material. Front. Agron. 2025, 7, 1545015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, N.; Poór, P. Plant Protection by Tannins Depends on Defence-Related Phytohormones. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2025, 44, 22–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zaynab, M.; Sharif, Y.; Khan, J.; Al-Yahyai, R.; Sadder, M.; Ali, M.; Alarab, S.R.; Li, S. Tannins as Antimicrobial Agents: Understanding Toxic Effects on Pathogens. Toxicon 2024, 247, 107812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargiacchi, E.; Miele, S.; Romani, A.; Campo, M. Biostimulant Activity of Hydrolyzable Tannins from Sweet Chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.). In Proceedings of the I World Congress on the Use of Biostimulants in Agriculture, Strasbourg, France, 26–29 November 2012; pp. 111–116. [Google Scholar]

- Ru, I.T.K.; Sung, Y.Y.; Jusoh, M.; Wahid, M.E.A.; Nagappan, T. Chlorella vulgaris: A Perspective on Its Potential for Combining High Biomass with High Value Bioproducts. Appl. Phycol. 2020, 1, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronga, D.; Biazzi, E.; Parati, K.; Carminati, D.; Carminati, E.; Tava, A. Microalgal Biostimulants and Biofertilisers in Crop Productions. Agronomy 2019, 9, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-M.; Kim, S.-K.; Lee, N.; Ahn, C.-Y.; Ryu, C.-M. D-Lactic Acid Secreted by Chlorella Fusca Primes Pattern-Triggered Immunity against Pseudomonas Syringae in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2020, 102, 761–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Morais, M.G.; Vaz, B.D.S.; de Morais, E.G.; Costa, J.A.V. Biologically Active Metabolites Synthesized by Microalgae. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 835761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atia, A.M.; Heikal, Y.M.; Eltanahy, E. Isolation, Cultivation of Freshwater Chlorophyta and Screening of the Synthesized Bioactive Compounds and Phytohormone. Mansoura J. Biol. 2024, 71, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, C.; Genevace, M.; Gama, F.; Coelho, L.; Pereira, H.; Varela, J.; Reis, M. Chlorella vulgaris and Tetradesmus obliquus Protect Spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.) against Fusarium oxysporum. Plants 2024, 13, 1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khojiakhmatov, S.; Turdiyev, B.; Eliboyeva, S.; Khodjayeva, N. The Application of Chlorella in Agriculture. Int. J. Divers. Multicult. 2025, 2, 88–91. [Google Scholar]

- Meneguzzo, F.; Brunetti, C.; Fidalgo, A.; Ciriminna, R.; Delisi, R.; Albanese, L.; Zabini, F.; Gori, A.; dos Santos Nascimento, L.B.; De Carlo, A.; et al. Real-Scale Integral Valorization of Waste Orange Peel via Hydrodynamic Cavitation. Processes 2019, 7, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scurria, A.; Sciortino, M.; Presentato, A.; Lino, C.; Piacenza, E.; Albanese, L.; Zabini, F.; Meneguzzo, F.; Nuzzo, D.; Pagliaro, M.; et al. Volatile Compounds of Lemon and Grapefruit IntegroPectin. Molecules 2020, 26, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meneguzzo, F.; Albanese, L.; Faraloni, C.; Meneguzzo, C.; Tagliavento, L.; Zabini, F. Pilot Scale Tannin Extraction from Chestnut Wood Waste Using Hydrodynamic Cavitation. In Towards a Smart, Resilient and Sustainable Industry; Borgianni, Y., Matt, D.T., Molinaro, M., Orzes, G., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 745, pp. 437–447. ISBN 978-3-031-38273-4. [Google Scholar]

- APAT. Metodi Microbiologici Di Analisi Del Compost. In Manuali e Linee Guida 20/2003; APAT: Roma, Italy, 2003; ISBN 88-448-0090-X. [Google Scholar]

- Rippka, R.; Deruelles, J.; Waterbury, J.B.; Herdman, M.; Stanier, R.Y. Generic Assignments, Strain Histories and Properties of Pure Cultures of Cyanobacteria. Microbiology 1979, 111, 1–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Jian, W. Growth Conditions and Growth Kinetics of Chlorella vulgaris Cultured in Domestic Sewage. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillard, R.R.; Sieracki, M.S. Counting Cells in Cultures with the Light Microscope. In Algal Culturing Techniques; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 239–252. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Y.J.; Park, J.-E.; Truong, T.Q.; Koo, S.Y.; Choi, J.-H.; Kim, S.M. Effect of Chlorella vulgaris on the Growth and Phytochemical Contents of “Red Russian” Kale (Brassica napus var. Pabularia). Agronomy 2022, 12, 2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasser, B.J.; Strasser, R.J. Measuring Fast Fluorescence Transients to Address Environmental Questions: The JIP-Test. In Photosynthesis: From Light to Biosphere; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Appenroth, K.-J.; Stöckel, J.; Srivastava, A.; Strasser, R. Multiple Effects of Chromate on the Photosynthetic Apparatus of Spirodela Polyrhiza as Probed by OJIP Chlorophyll a Fluorescence Measurements. Environ. Pollut. 2001, 115, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.; Riley, J.P. A Modified Single Solution Method for the Determination of Phosphate in Natural Waters. Anal. Chim. Acta 1962, 27, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miele, S.; Tegli, S.; Izquierdo, C.G.; Cerboneschi, M.; Bargiacchi, E. Hydrolysable Tannins in Agriculture. In Tannins-Structural Properties, Biological Properties and Current Knowledge; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Refaay, D.A.; El-Marzoki, E.M.; Abdel-Hamid, M.I.; Haroun, S.A. Effect of Foliar Application with Chlorella vulgaris, Tetradesmus dimorphus, and Arthrospira platensis as Biostimulants for Common Bean. J. Appl. Phycol. 2021, 33, 3807–3815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Bella, E.; Baglieri, A.; Rovetto, E.I.; Stevanato, P.; Puglisi, I. Foliar Spray Application of Chlorella vulgaris Extract: Effect on the Growth of Lettuce Seedlings. Agronomy 2021, 11, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haroun, S.; Hussein, M. The Promotive Effect of Algal Biofertilizers on Growth, Protein Pattern and Some Metabolic Activities of Lupinus Termis Plants Grown in Siliceous Soil. Asian J Plant Sci 2003, 2, 944–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaiese, P.; Corrado, G.; Colla, G.; Kyriacou, M.C.; Rouphael, Y. Renewable Sources of Plant Biostimulation: Microalgae as a Sustainable Means to Improve Crop Performance. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žunić, V.; Hajnal-Jafari, T.; Stamenov, D.; Djurić, S.; Tomić, J.; Pešaković, M.; Grohar, M.C.; Stampar, F.; Veberic, R.; Hudina, M.; et al. Application of Microalgae-Based Biostimulants in Sustainable Strawberry Production. J. Appl. Phycol. 2024, 36, 1219–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brain, K.; Chalopin, M.; Turner, T.; Blunden, G.; Wildgoose, P. Cytokinin Activity of Commercial Aqueous Seaweed Extract. Plant Sci. Lett. 1973, 1, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshghi, S.; Jamali, B. Leaf and Fruit Mineral Composition and Quality in Relation to Production of Malformed Strawberry Fruits. Hort. Env. Biotech 2009, 50, 397–400. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.-N.; Choi, J.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Yoon, Y.-E.; Choe, H.; Lee, K.-A.; Kantharaj, V.; Kim, M.-J.; Lee, Y.B. Biostimulatory Effects of Chlorella Fusca CHK0059 on Plant Growth and Fruit Quality of Strawberry. Plants 2023, 12, 4132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Date | T | Experiment Activity | Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| 28 April | Fertilization with nutrient solution | ||

| 13 June | Fertilization with nutrient solution | ||

| 27 June | T0 | Start of C.v and tannin treatments | C.f. |

| 4 July | C.v and tannin treatment | ||

| 11 July | C.v and tannin treatment | ||

| 18 July | C.v and tannin treatment | ||

| 19 July | T1 | Performance and production evaluation | FFP; C.f. |

| 26 July | T2 | C.v and tannin treatment | |

| 1 August | T3 | Production evaluation | FFP |

| 2 August | C.v and tannin treatment | ||

| 10 August | C.v and tannin treatment | ||

| 22 August | T4 | Performance and production evaluation | FFP; C.f.; LGE; Pigm |

| 29 August | C.v and tannin treatment | ||

| 12 September | T5 | End of C.v and tannin treatments | Bio; C.f.; FFP; M.E. |

| 31 October | T6 | End of experiment | Bio; C.f.; LGE; Pigm |

| G (%) | Radicle Length (mm) | Ig (%) | Gfin (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTRL | 92% ± 18% | 5.00 ± 1.58 | 100% ± 0% | |

| 50% T | 76% ± 21% | 2.92 ± 0.91 | 48% | 96% ± 9% |

| 75% T | 88% ± 13% | 3.44 ± 1.28 | 66% | 98% ± 4% |

| 100% T | 90% ± 12% | 3.65 ± 0.95 | 71% | 96% ± 5% |

| CNT | COM | 13% T.E. | 27% T.E. | 54% T.E. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaves FW (g) | 0.62 ± 0.19 bc | 0.68 ± 0.05 b | 0.55 ± 0.04 c | 0.69 ± 0.24 bc | 0.86 ± 0.07 a |

| Stem FW (g) | 0.64 ± 0.11 ns | 0.72 ± 0.13 ns | 0.64 ± 0.19 ns | 0.63 ± 0.18 ns | 0.81 ± 0.35 ns |

| Root FW (g) | 5.01 ± 0.65 ns | 5.7 ± 0.62 ns | 4.84 ± 1.20 ns | 4.89 ± 1.53 ns | 4.22 ± 0.33 ns |

| Total FW (g) | 6.26 ± 0.70 ns | 6.35 ± 0.15 ns | 6.03 ± 1.30 ns | 6.22 ± 1.8 ns | 5.80 ± 0.81 ns |

| Leaves DW (g) | 0.12 ± 0.04 b | 0.14 ± 0.00 b | 0.11 ± 0.04 b | 0.15 ± 0.07 b | 0.21 ± 0.05 a |

| Stem DW (g) | 0.09 ± 0.04 ns | 0.07 ± 0.03 ns | 0.08 ± 0.03 ns | 0.08 ± 0.04 ns | 0.10 ± 0,03 ns |

| Root DW (g) | 1.11 ± 0.21 ns | 1.26 ± 0.24 ns | 1.00 ± 0.30 ns | 1.15 ± 0.50 ns | 1.13 ± 0.12 ns |

| Total DW (g) | 1.19 ± 0.20 ns | 1.32 ± 0.5 ns | 1.07 ± 0.30 ns | 1.23 ± 0.50 ns | 1.23 ± 0.10 ns |

| Aerial part/root (FW) | 0.25 ± 0.05 ab | 0.22 ± 0.05 b | 0.26 ± 0.07 ab | 0.28 ± 0.07 ab | 0.40 ± 0.09 a |

| Aerial part/root (DW) | 0.19 ± 0.09 ns | 0.17 ± 0.06 ns | 0.20 ± 0.08 ns | 0.21 ± 0.05 ns | 0.28 ± 0.09 ns |

| N main roots/plant | 48.8 ± 9.2 b | 128.8 ± 57.5 a | 94.2 ± 50 a | 121.5 ± 59.3 a | 117.2 ± 55 a |

| N sec roots/plant | 34.8 ± 25.3 ab | 27.5 ± 7.7 ab | 13.6 ± 18 b | 43 ± 27 a | 49.8 ± 16.5 a |

| Main root L (mm) | 125.1 ± 48.7 ns | 103.9 ± 24.8 ns | 102.1 ± 27.3 ns | 100.6 ± 22.8 ns | 119.2 ± 12 ns |

| Sec root L (mm) | 40.5 ± 11 ns | 48.1 ± 8.3 ns | 35.2 ± 11.4 ns | 43.1 ± 10.5 ns | 64.1 ± 25.1 ns |

| Chlorophyll (µg cm−2) | 30.96 ± 1.95 a | 29.56 ± 2.23 bc | 28.85 ± 2.56 c | 31.25 ± 1.55 a | 30.62 ± 2.45 ab |

| Flavonols | 0.03 ± 0.02 ns | 0.08 ± 0.08 ns | 0.07 ± 0.06 ns | 0.02 ± 0.02 ns | 0.11 ± 0.01 ns |

| Anthocyanins | 0.02 ± 0.014 ns | 0.01 ± 0.01 ns | 0.01 ± 0.01 ns | -- | 0.01 ± 0.01 ns |

| CNT | C1 | C2 | T | T+C1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FW Leaf (g) | 13.82 ± 1.96 ab | 15.72 ± 0.05 a | 12.51 ± 1.69 ab | 11.16 ± 0.08 b | 10.15 ± 2.77 b |

| DW Leaf (g) | 3.10 ± 0.45 ns | 3.34 ± 0.63 ns | 2.89 ± 0.27 ns | 3.08 ± 0.97 ns | 2.37 ± 0.53 ns |

| FW Root (g) | 30.12 ± 3.89 bc | 36.22 ± 3.1 ab | 31.04 ± 1.94 abc | 24.55 ± 4.76 c | 39.75 ± 5.67 a |

| DW Root (g) | 5.12 ± 0.07 b | 5.88 ± 0.03 b | 4.90 ± 0.1 b | 5.11 ± 0.07 b | 7.22 ± 0.03 a |

| FW Stem (g) | 3.18 ± 1.17 ns | 1.53 ± 0.20 ns | 2.25 ± 0.68 ns | 2.12 ± 0.69 ns | 1.25 ± 0.41 ns |

| DW Stem (g) | 0.40 ± 0.17 ns | 0.26 ± 0.05 ns | 0.38 ± 0.15 ns | 0.24 ± 0.02 ns | 0.22 ± 0.09 ns |

| FW Aerial Part (g) | 16.45 ± 3.03 a | 16.57 ± 2.12 a | 14.20 ± 0.09 ab | 13.40 ± 1.59 ab | 11.69 ± 2.58 b |

| DW Aerial part (g) | 3.4 ± 0.64 ns | 3.28 ± 0.42 ns | 2.59 ± 0.61 ns | 3.26 ± 0.91 ns | 3.6 ± 0.61 ns |

| Aerial Part/Root (FW) | 0.58 ± 0.16 ns | 0.48 ± 0.04 ns | 0.48 ± 0.10 ns | 0.55 ± 0.07 ns | 0.29 ± 0.09 ns |

| Aerial Part/Root (DW) | 0.70 ± 0.26 ns | 0.61 ± 0.19 ns | 0.67 ± 0.14 ns | 0.64 ± 0.32 ns | 0.35 ± 0.13 ns |

| Chlorophyll | Flavonols | Anthocyanins | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T4 | T6 | T4 vs. T6 | T4 | T6 | T4 vs. T6 | T4 | T6 | T4 vs. T6 | |

| CNT | 25.1 ± 2.5 ns | 32.7 ± 2.6 ns | ** | 1.2 ± 0.1 ns | 1.1 ± 0.4 ns | ns | 0.03 ± 0.01 ns | 0.013 ± 0.00 ns | n.a. |

| C1 | 26.4 ± 1 ns | 29.8 ± 1.8 ns | * | 1.2 ± 0.1 ns | 1.3 ± 0.1 ns | ns | 0.022 ± 0.00 ns | 0.013 ± 0.01 ns | n.a. |

| C2 | 27.3 ± 3.5 ns | 29.2 ± 2 ns | ns | 1.2 ± 0.2 ns | 1.2 ± 0.1 ns | ns | 0.033 ± 0.01 ns | 0.015 ± 0.01 ns | n.a. |

| T | 26.2 ± 2.1 ns | 27.9 ± 4.2 ns | ns | 1.2 ± 0.2 ns | 1.1 ± 0.5 ns | ns | 0.026 ± 0.01 ns | 0.02 ± 0.01 ns | n.a. |

| T+C1 | 25.6 ± 1.3 ns | 28.4 ± 2.4 ns | ns | 1.4 ± 0 ns | 1.2 ± 0.1 ns | ns | 0.036 ± 0.01 ns | 0.014 ± 0.00 ns | n.a. |

| Time | Treatment | VJ | Fv/Fm | φEo |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | 0.468 ± 0.059 | 0.721 ± 0.041 | 0.385 ± 0.061 | |

| T1 | CNT | 0426 ± 0.038 | 0.768 ± 0.020 AB | 0.441 ± 0.029 |

| C1 | 0.435 ± 0.044 | 0.764 ± 0.024 AB | 0.431 ± 0.035 | |

| C2 | 0.465 ± 0.080 | 0.746 ± 0.054 | 0.402 ± 0.080 | |

| T | 0.464 ± 0.045 | 0.782 ± 0.005 | 0.419 ± 0.034 | |

| T+C1 | 0.426 ± 0.065 | 0.758 ± 0.035 AB | 0.435 ± 0.049 | |

| T4 | CNT | 0.424 ± 0.001 | 0.781 ± 0.003 AB | 0.439 ± 0.008 |

| C1 | 0.441 ± 0.001 | 0.781 ± 0.003 AB | 0.440 ± 0.004 | |

| C2 | 0.453 ± 0.002 | 0.774 ± 0.007 | 0.429 ± 0.008 | |

| T | 0.454 ± 0.002 | 0.782 ± 0.005 | 0.431 ± 0.002 | |

| T+C1 | 0.436 ± 0.001 | 0.775 ± 0.006 A | 0.434 ± 0.001 | |

| T5 | CNT | 0.423 ± 0.025 | 0.800 ± 0.022 A | 0.462 ± 0.031 |

| C1 | 0.446 ± 0.029 | 0.797 ± 0.026 A | 0.441 ± 0.029 | |

| C2 | 0.441 ± 0.048 | 0.782 ± 0.024 | 0.437 ± 0.036 | |

| T | 0.446 ± 0.031 | 0.797 ± 0.018 | 0.441 ± 0.033 | |

| T+C1 | 0.445 ± 0.057 | 0.786 ± 0.023 A | 0.436 ± 0.044 | |

| T6 | CNT | 0.681 ± 0.062 | 0.622 ± 0.043 B | 0.203 ± 0.017 |

| C1 | 0.336 ± 0.056 | 0.648 ± 0.011 B | 0.432 ± 0.205 | |

| C2 | 0.448 ± 0.030 | 0.667 ± 0.096 | 0.339 ± 0.003 | |

| T | 0.421 ± 0.019 | 0.687 ± 0.013 | 0.350 ± 0.002 | |

| T+C1 | 0.451 ± 0.064 | 0.658 ± 0.083 B | 0.337 ± 0.022 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Giordano, C.; Ugolini, F.; Faraloni, C.; Dal Prà, A.; Sabatini, F.; Meneguzzo, F.; Petruccelli, R. Beyond Conventional Fertilizer: Tannin–Chlorella vulgaris Blends as Biostimulants for Growth and Yield Enhancement of Strawberry (Fragaria x ananassa Duch). Agriculture 2025, 15, 2459. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232459

Giordano C, Ugolini F, Faraloni C, Dal Prà A, Sabatini F, Meneguzzo F, Petruccelli R. Beyond Conventional Fertilizer: Tannin–Chlorella vulgaris Blends as Biostimulants for Growth and Yield Enhancement of Strawberry (Fragaria x ananassa Duch). Agriculture. 2025; 15(23):2459. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232459

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiordano, Cristiana, Francesca Ugolini, Cecilia Faraloni, Aldo Dal Prà, Francesco Sabatini, Francesco Meneguzzo, and Raffaella Petruccelli. 2025. "Beyond Conventional Fertilizer: Tannin–Chlorella vulgaris Blends as Biostimulants for Growth and Yield Enhancement of Strawberry (Fragaria x ananassa Duch)" Agriculture 15, no. 23: 2459. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232459

APA StyleGiordano, C., Ugolini, F., Faraloni, C., Dal Prà, A., Sabatini, F., Meneguzzo, F., & Petruccelli, R. (2025). Beyond Conventional Fertilizer: Tannin–Chlorella vulgaris Blends as Biostimulants for Growth and Yield Enhancement of Strawberry (Fragaria x ananassa Duch). Agriculture, 15(23), 2459. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232459