Enhancing the Marketization and Globalization Response Capacity of Policies: Evolution of China’s Seed Industry Policies Since the 21st Century

Abstract

1. Introduction

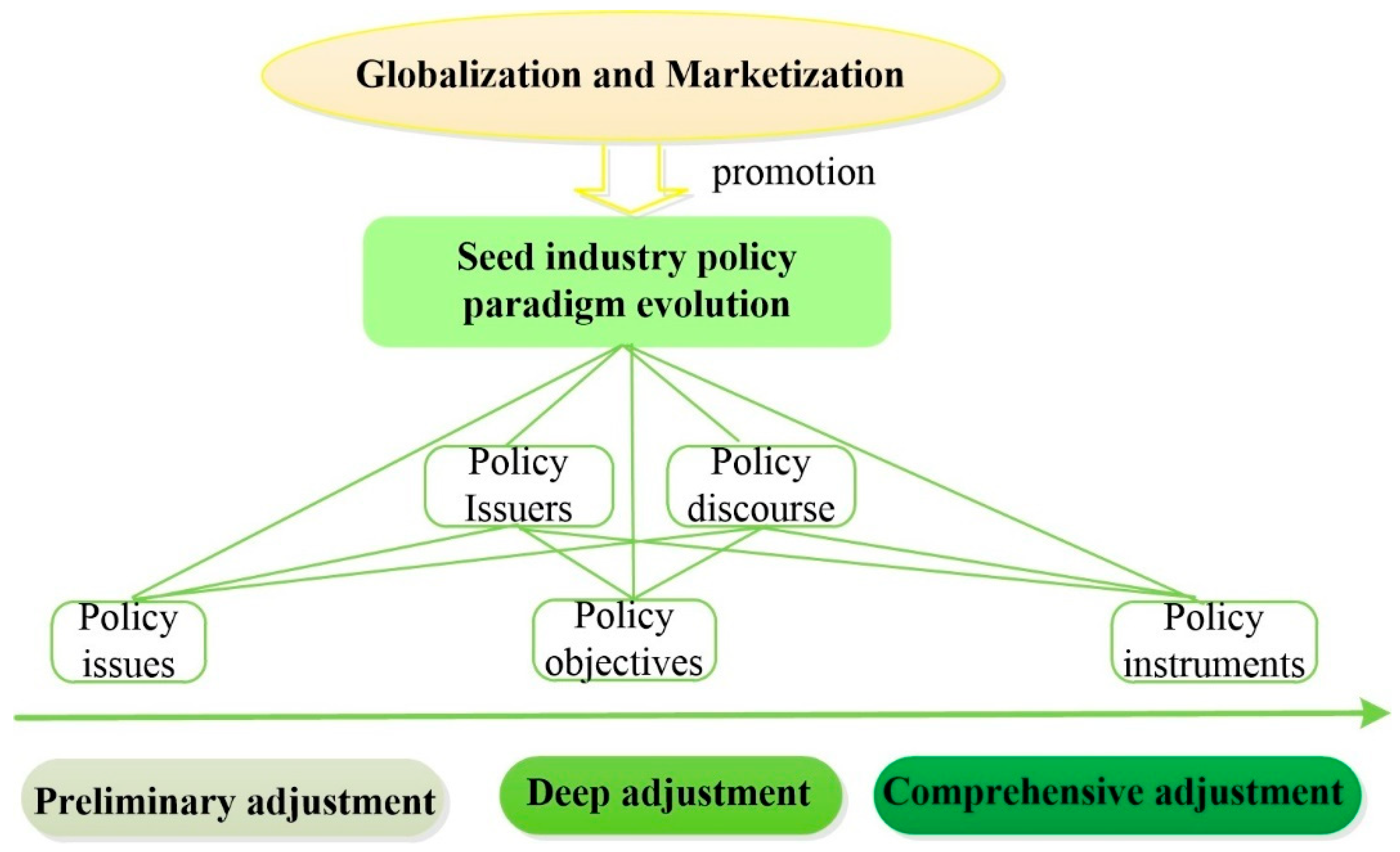

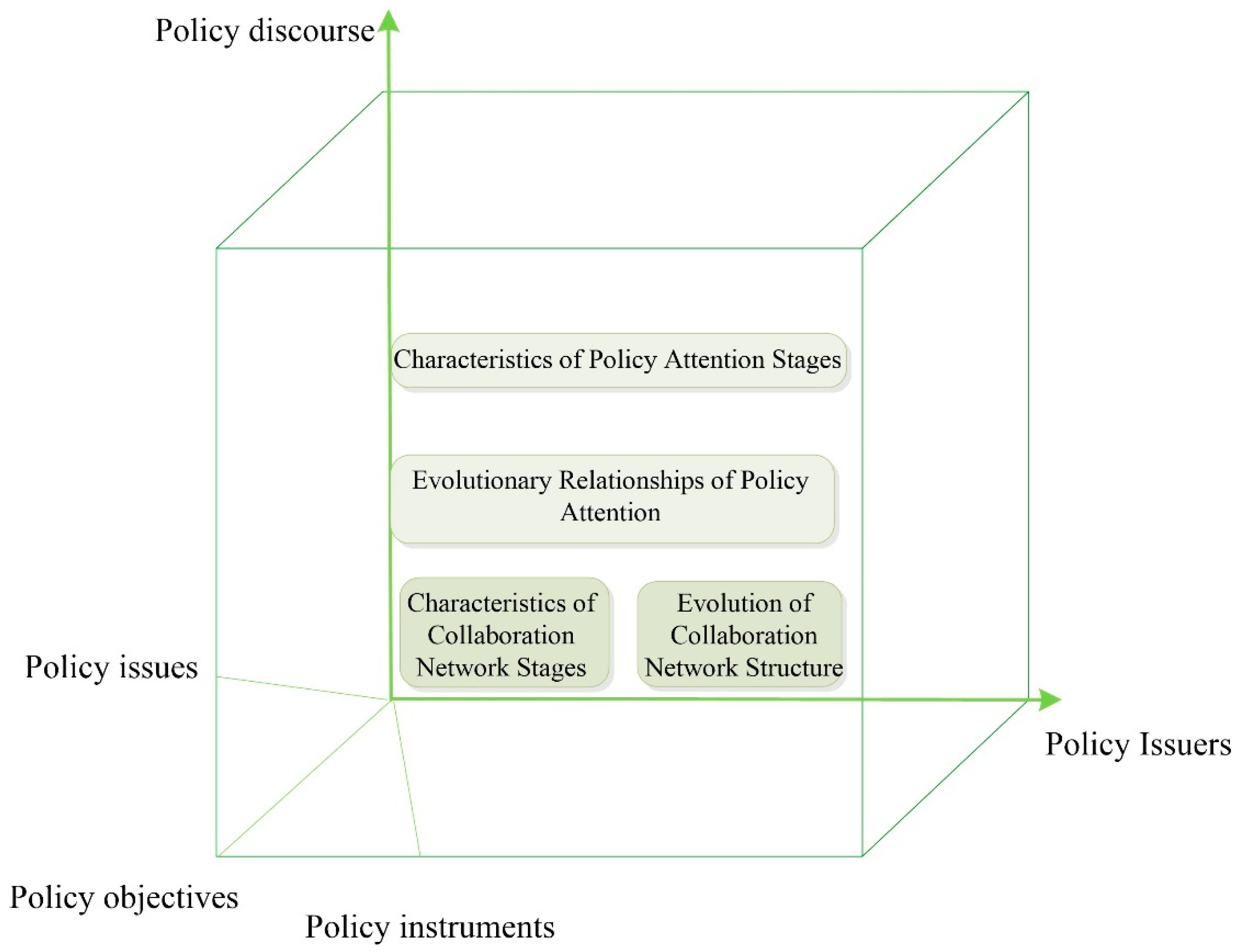

2. Theoretical Framework and Overview of the Development of Seed Industry Policies

2.1. Theoretical Framework

2.2. Overview of the Development of Seed Industry Policies

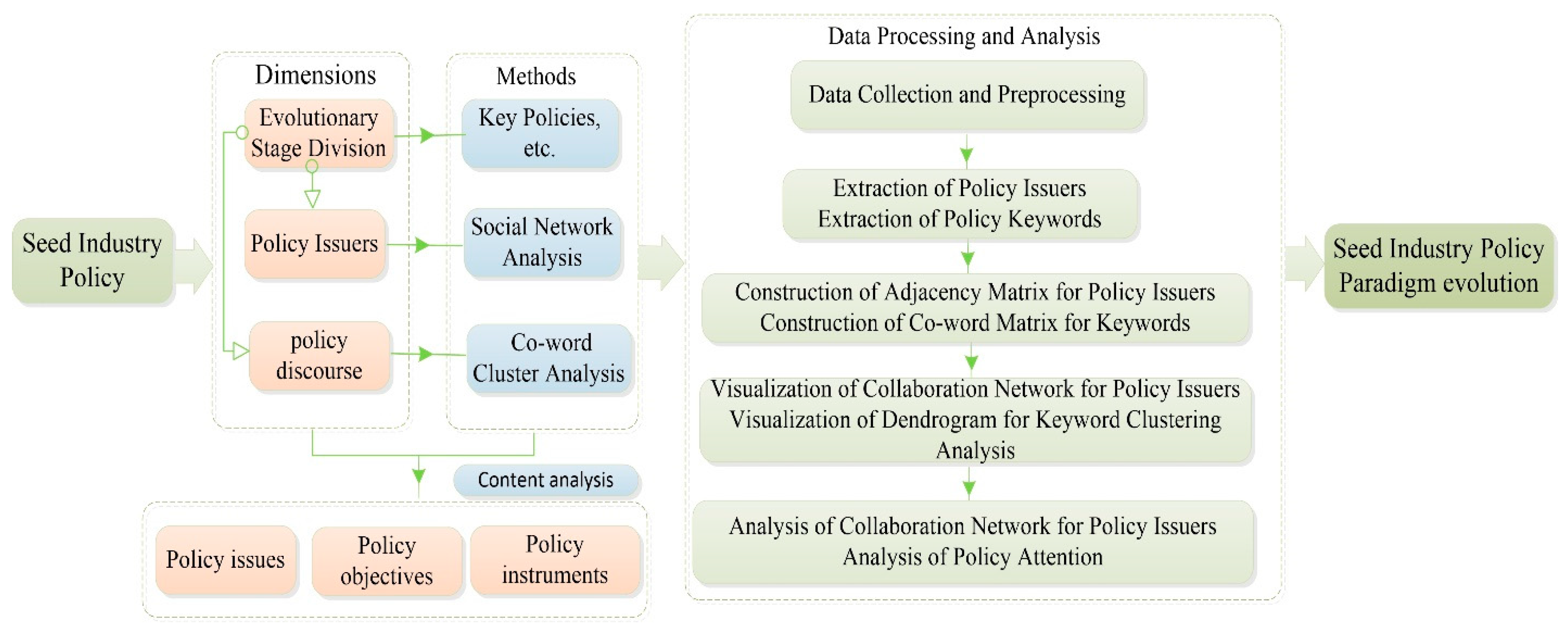

3. Data Sources and Research Methods

3.1. Data Source and Processing

3.2. Research Method

4. Result

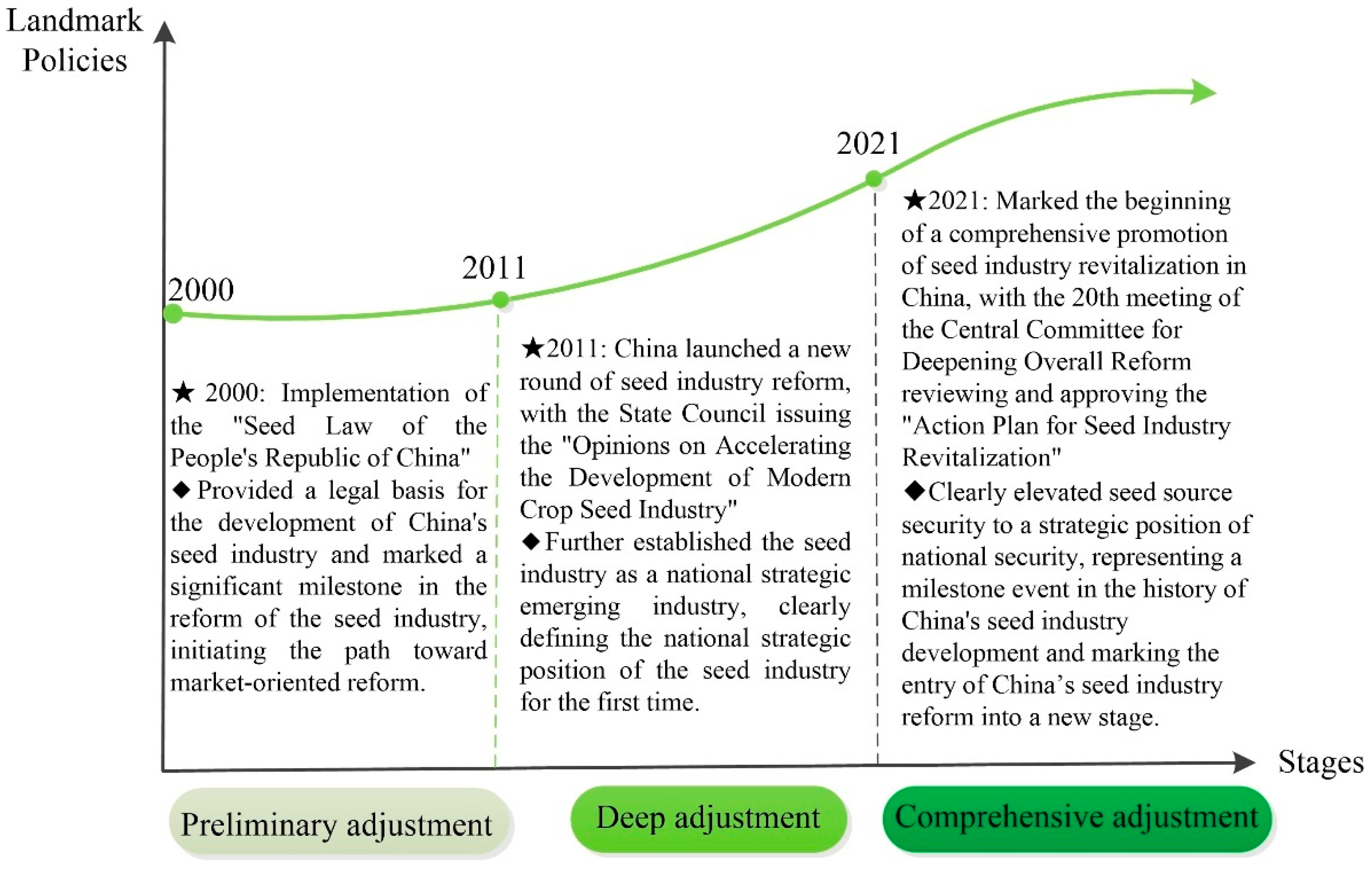

4.1. Stages of Policy Evolution

4.2. Evolution of the Cooperative Network Among Policy Issuers

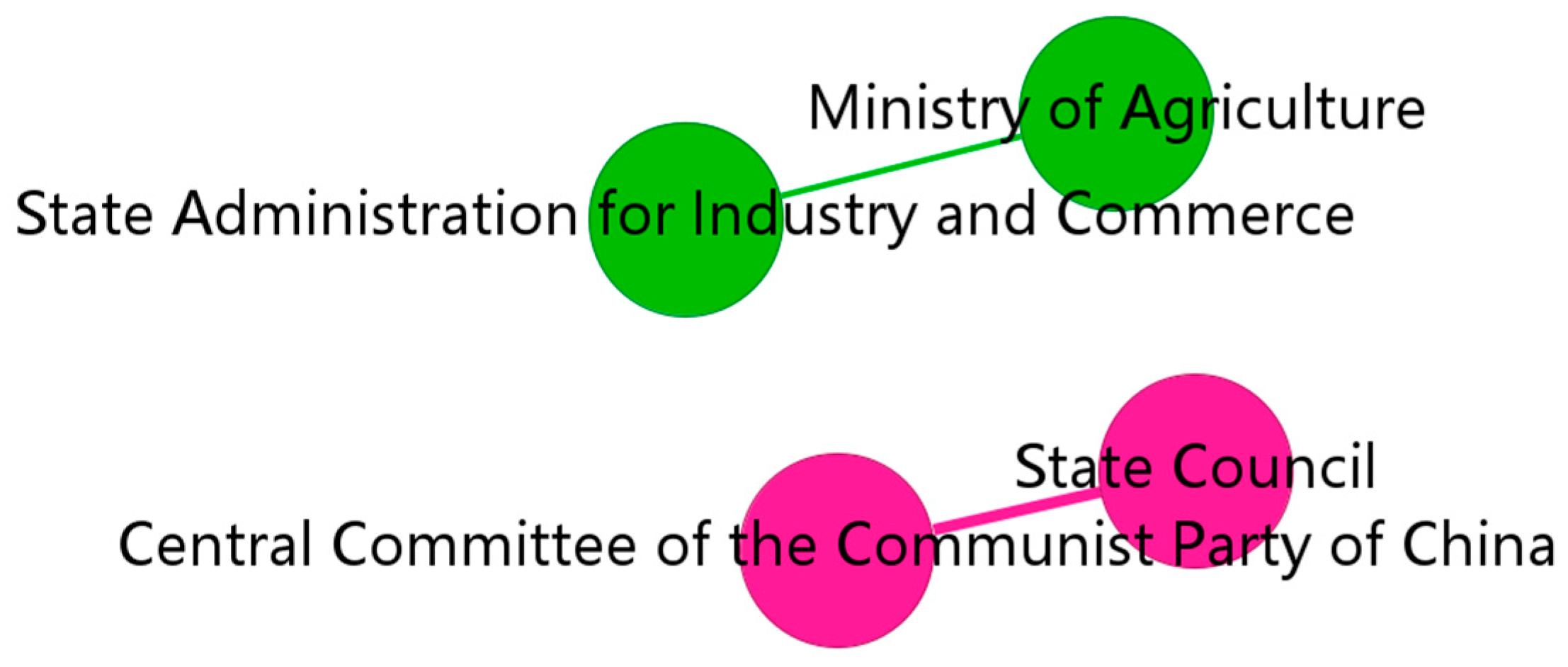

- (1)

- Cooperative Networks during the Preliminary Adjustment Period (2000–2010)

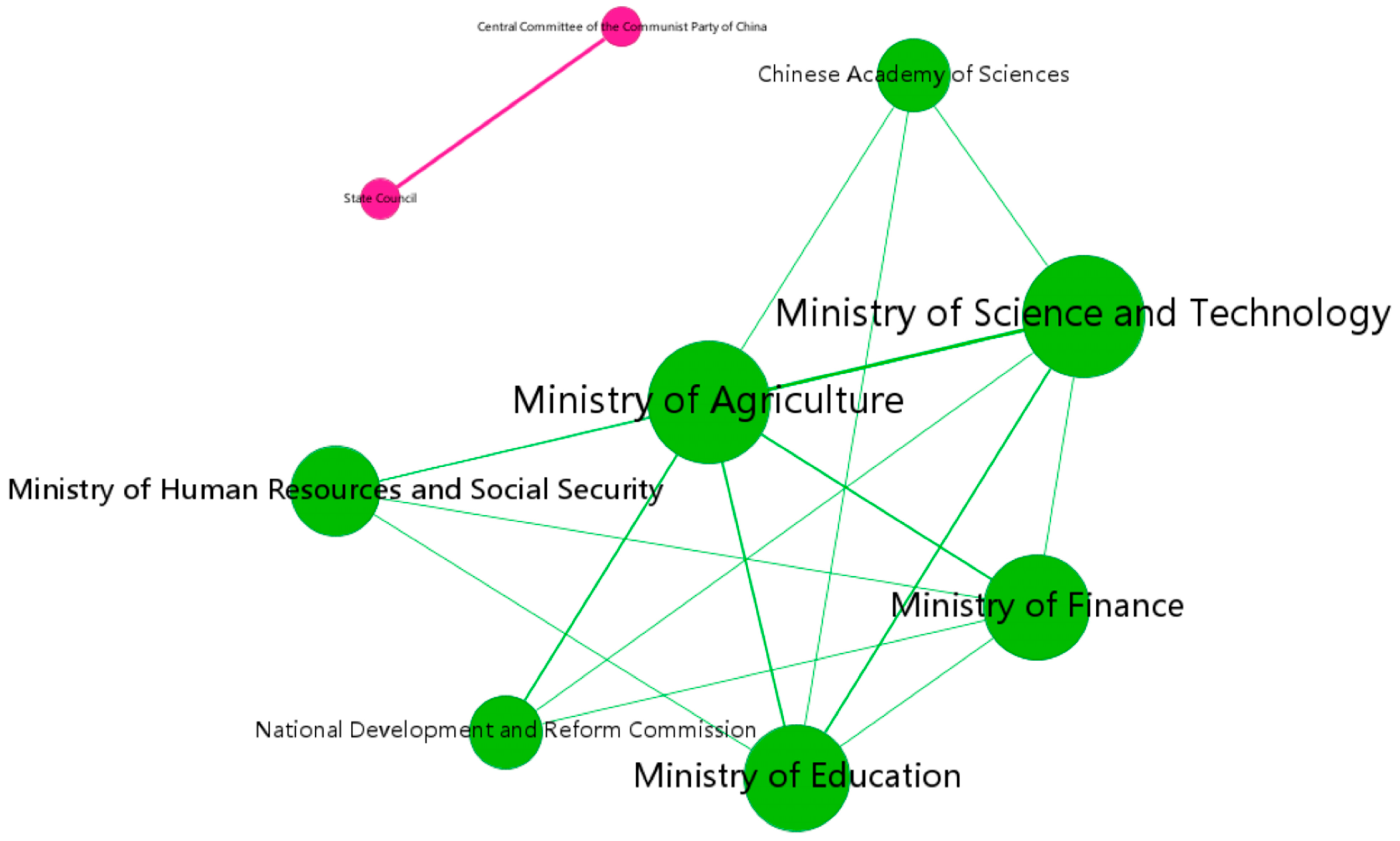

- (2)

- Cooperative Networks during the Deepening Adjustment Period (2011–2020)

- (3)

- Cooperative Networks during the Comprehensive Adjustment Period (2021–2024)

4.3. Evolution of Policy Discourse

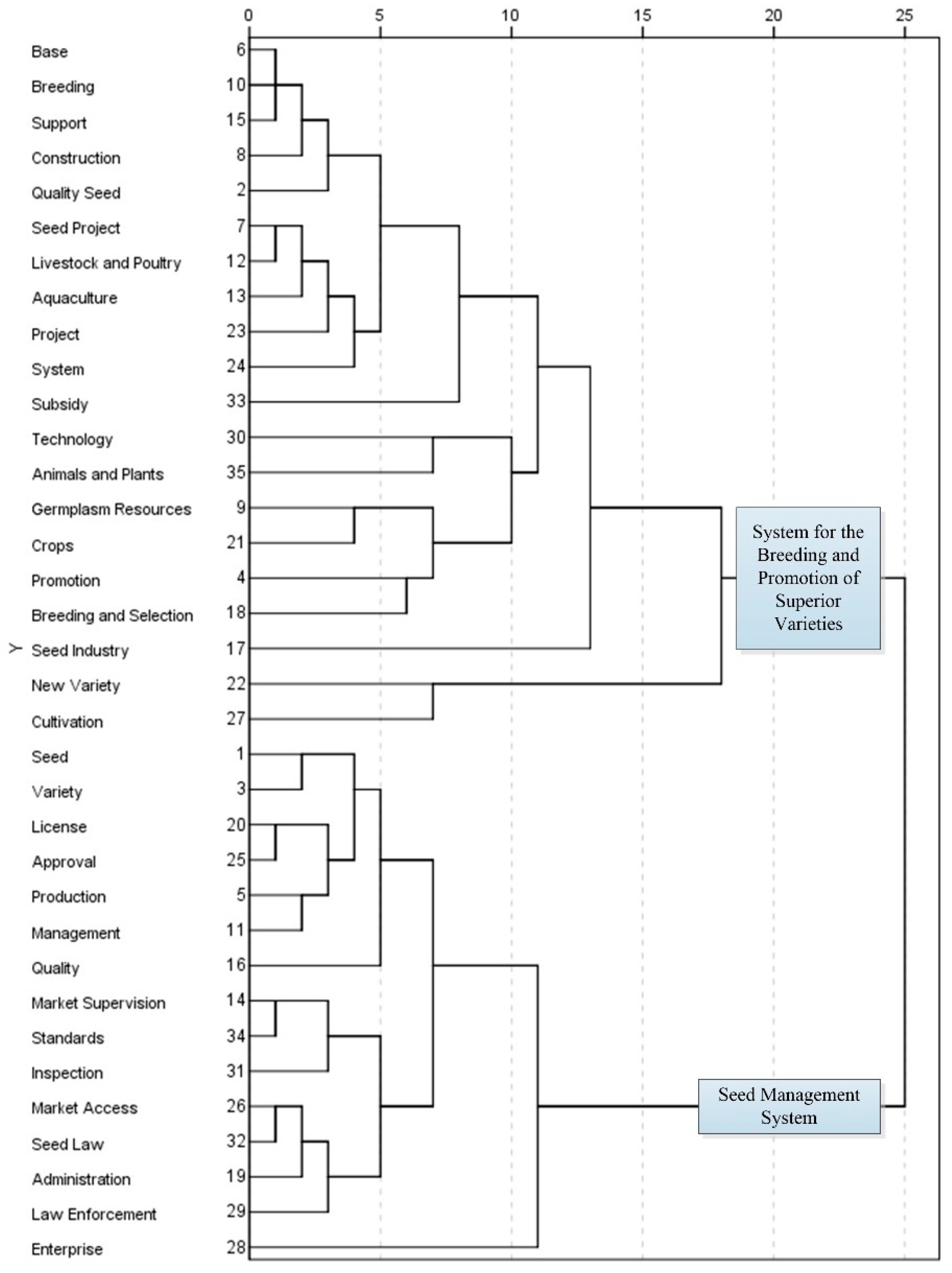

- (1)

- Policy Discourse during the Preliminary Adjustment Period (2000–2010)

- (2)

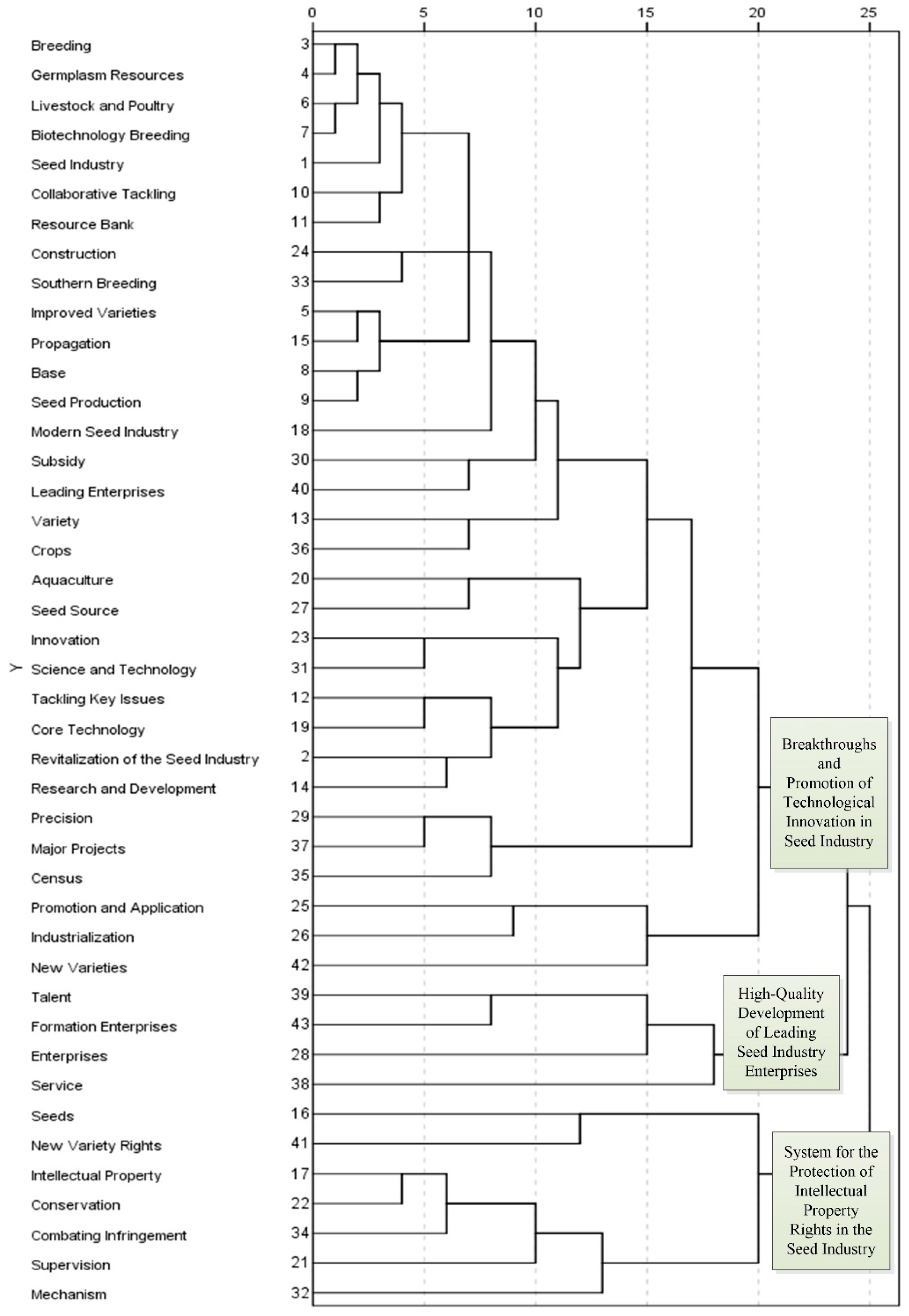

- Policy Discourse during the Deepening Adjustment Period (2011–2020)

- (3)

- Policy Discourse during the Comprehensive Adjustment Period (2021–2024)

4.4. Evolution of Policy Paradigms

- (1)

- Recognition of Policy Issues

- (2)

- Positioning of Policy Objectives

- (3)

- Selection of Policy Tools

5. Policy Evolution Logic

5.1. Management Philosophy: From Regulation to Service

5.2. Support for Technological Innovation: From Single to Diverse Innovation

5.3. Breeding and Promotion of Quality Seeds: Progressing from Low to High Levels

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

- (1)

- Since the beginning of the 21st century, China’s seed industry policies have largely aligned with broader trends of marketization and globalization. The evolution process has encompassed three stages: the market-oriented transformation of the seed industry, responses to global challenges, and the modernization and self-strengthening of the sector. A comprehensive and distinctive seed industry policy system has thus been established. During this period, policies have advanced progressively, with an increasing number of policy documents and growing influence. The evolution of China’s seed industry policies exhibits a progressive characteristic. In response to intensifying international market competition and the advent of the fourth technological revolution, China has responded promptly and effectively to regulate seed industry development. The pace of policy evolution has accelerated, and the capacity of seed industry policies to address marketization and globalization challenges has continually improved, ensuring the security of China’s seed industry and food supply.

- (2)

- In the context of marketization and globalization, the cooperative network of policy issuers has gradually expanded and become more complex. An increasing number of entities are participating in the formulation of seed policies, reflecting a trend toward diversification among policy issuers. From the perspective of network density, as the cooperative network expands, the degree of interaction among policy issuers has decreased, showing a trend of initial increase followed by a decline, indicating a relatively loose interaction among policy issuers. The centrality index has gradually risen, suggesting a decreasing level of balance within the network, with the power dynamics among departments shifting from “balanced” to “relatively concentrated” and then to “concentrated.” The cooperative network is evolving toward a loose-centralized structure, demonstrating trends of diversification and centralization, with inter-departmental collaboration becoming an important mechanism for formulating seed policies.

- (3)

- Under the context of marketization and globalization, the evolution of policy discourse exhibits clear stage-specific characteristics. During the initial adjustment period, policies primarily focused on the cultivation and promotion of excellent seed varieties and seed management systems. In the deepening adjustment phase, attention shifted to reform and innovation within the seed industry system, capacity building in biological breeding, and the protection of genetic resources. By the comprehensive adjustment period, policies emphasized technological innovation and research in seed science and technology, high-quality development of leading seed enterprises, and the establishment of an intellectual property protection system for the seed industry. Overall, policy priorities demonstrate an evolution from creating a market-oriented environment to fostering an environment conducive to seed industry innovation and development, and finally to enhancing foundational research and development capabilities, tackling key technological challenges in seed innovation, and promoting industrialization.

- (4)

- With changes in the policy environment driven by marketization and globalization, policy issues, objectives, and instruments have continuously evolved. This ongoing process has driven the transition of seed policies from initial adjustment and deepening adjustment stages to a comprehensive adjustment phase, with the paradigm shifting from the early-stage market-oriented transformation to the modern, self-reliant development model of the seed industry. Policy issues have shifted from problems such as imperfect market mechanisms and inadequate regulation to bottlenecks in seed sources (‘bottleneck’ issues). Policy objectives have moved from reforming and improving seed management and strengthening market regulation to achieving technological independence, self-sufficiency in seed sources, and control over seed supply. The policy tools have transitioned from predominantly market regulation to a diversified set of instruments supporting technological innovation through coordinated efforts.

- (5)

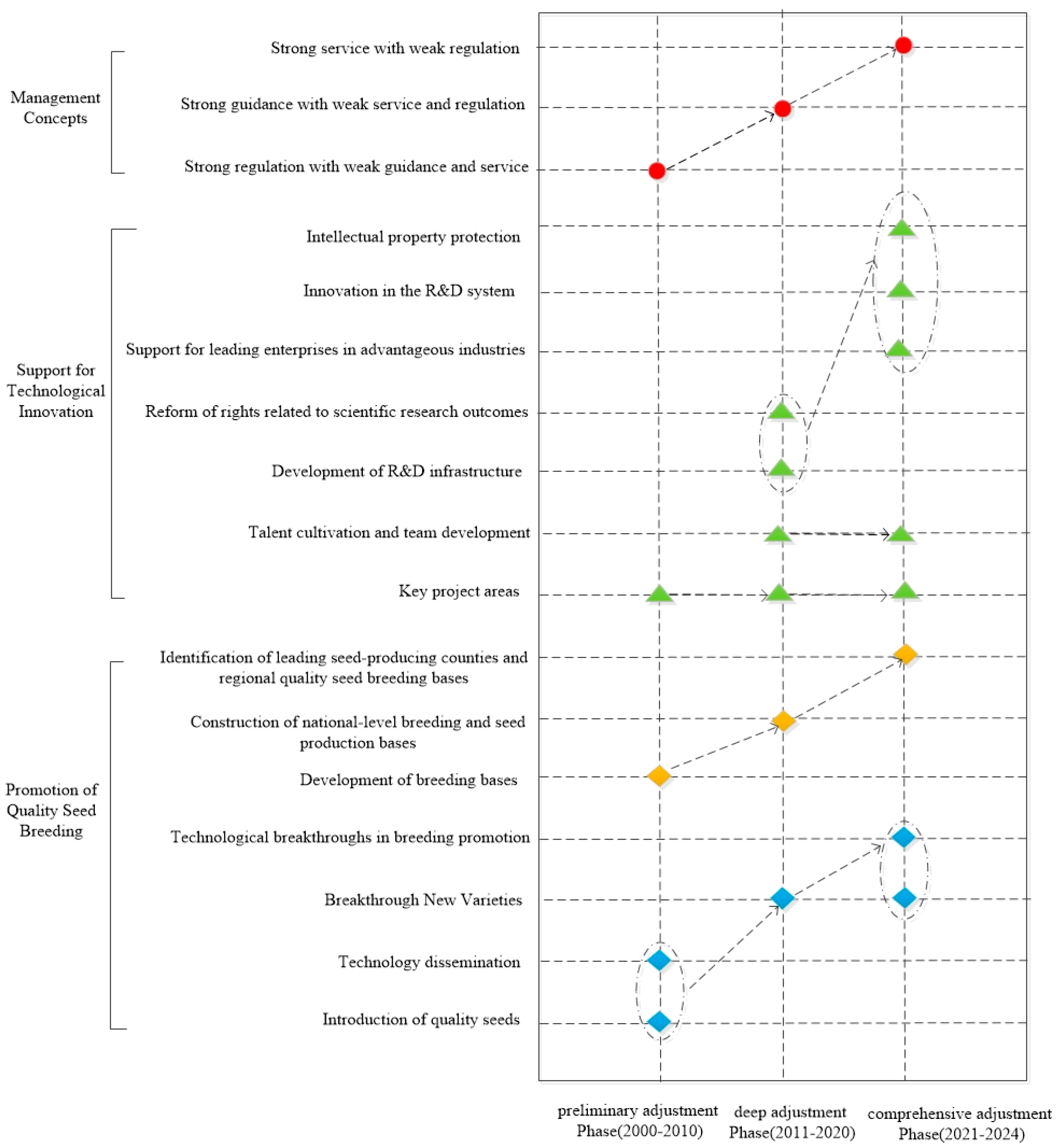

- The logic of policy evolution shows distinct differences in management philosophy, support for technological innovation, and emphasis on seed breeding and promotion. Firstly, in terms of management philosophy, seed policies have evolved from predominantly regulation-based policies, complemented by guiding and service-oriented policies, to a mode dominated by guiding and regulatory policies, supported by service-oriented ones, and finally toward policies characterized by service-oriented and guiding functions with regulation serving as support. Secondly, concerning support for scientific and technological innovation, awareness has steadily increased, shifting from reliance on good varieties and technology importation and absorption towards self-reliance, independent innovation, and reliance on domestic technological strength. The focus has shifted from protecting germplasm resources and ensuring seed source security to creative breeding materials, with the leading role of enterprises in technological innovation gradually strengthening. Policy tools have progressed from single support mechanisms to diversified and innovative support instruments. Third, in seed breeding and promotion, the construction of breeding bases has transitioned from centralized national key projects to more open regional identification, resulting in the widespread dissemination of seed breeding bases across the country to secure seed supply and food security. Breeding and promotion technologies have shifted from early-stage technology introduction and propaganda to independent breakthroughs of key core technologies.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, J.; Chen, L. Chinese-Style Modernization of Agricultural Product Circulation: Evolutionary Pathways and Development Prospects. Soc. Sci. J. 2025, 3, 116–125. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lasswell, H.D. Power and Society: A Framework for Political Inquiry; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, S.; Wu, X.; Cang, Y. Exploring business environment policy changes in china using quantitative text analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Zhou, Y. Potential food security risks and countermeasures under the background of seed industry innovation based on industry 4.0. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2022, 2022, 9905894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Sun, Z.; Wang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Yang, W. Seeds of cross-sector collaboration: A multi-agent evolutionary game theoretical framework illustrated by the breeding of salt-tolerant rice. Agriculture 2024, 14, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielman, D.J.; Kennedy, A. Towards better metrics and policy making for seed system development: Insights from asia’s seed industry. Agric. Syst. 2016, 147, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spielman, D.J.; Kolady, D.E.; Cavalieri, A.; Rao, N.C. The seed and agricultural biotechnology industries in india: An analysis of industry structure, competition, and policy options. Food Policy 2014, 45, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, A.; Stubrin, L.; van Zwanenberg, P. Technological lock-in in action: Appraisal and policy commitment in argentina’s seed sector. Res. Policy 2023, 52, 104678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutra-Silva, R.; Overbeck, G.E.; Müller, S.C. How can brazilian legislation on native seeds advance based on good practices of restoration in other countries? Perspect. Ecol. Conserv. 2024, 22, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ningbo, C.; Shiyu, S. Strategic significance, realistic challenge and path remolding of high quality development of modern seed industry. Mod. Econ. Res. 2022, 2, 94–102. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jikun, H.; Ruifa, H. Seed industry in China: Achievements, challenge and future development. J. South China Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 22, 1–8. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ruixue, J. Research on the change of personal information governance policy themes and cross-departmental synergies in China. EGovernment 2022, 9, 73–87. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Wang, C.; Chen, J.; Liu, X.; Zhao, X. Policy evolution and analysis of characteristics and values of china’s marine seed industry development under the food security strategy. Mar. Policy 2023, 155, 105681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanjun, L.; Xinkai, Z.; Yanjun, L. The evolution of the scitech innovation provisions in the seed law: Motivation, characteristics and revelations. Forum Sci. Technol. China 2019, 12, 23–30. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, P.A. Policy paradigms, social learning, and the state: The case of economic policymaking in britain. Comp. Politics 1993, 25, 275–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, F.; Kuzemko, C.; Mitchell, C. Measuring and explaining policy paradigm change: The case of UK energy policy. Policy Politics 2014, 42, 513–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, C.; Zhaohan, C. Paradigm shift and new tendency of health policy in china—Based on content analysis of policy discourse. Chin. Public Adm. 2018, 9, 86–91. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y. Paradigm shifts in china’s housing policy: Tug-of-war between marketization and state intervention. Land Use Policy 2022, 122, 106387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Tao, R.; Jian, Z. Quantitative study of policy literature: A new direction of public policy research. J. Public Manag. 2015, 12, 129–137. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Yuanhao, L.; Cui, H.; Jun, S. Remolding the policy text data through documents quantitative research:the formation, transformation and method innovation of policy documents quantitative research. J. Public Manag. 2015, 12, 138–144. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, Z.A.; Jones, B.D. Reconceptualizing the policy subsystem: Integration with complexity theory and social network analysis. Policy Stud. J. 2019, 47, S138–S158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barabási, A.L.; Watts, D.J.; Newman, M. The Structure and Dynamics of Networks; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jun, L. A Practical Guide to UCINET Software; Gezhi Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Santillán-Fernández, A.; Salinas-Moreno, Y.; Valdez-Lazalde, J.R.; PereiraLorenzo, S. Spatial-temporal evolution of scientific production about genetically modified maize. Agriculture 2021, 11, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Chen, H.; Long, R.; Hou, C. Overview, evolution and thematic analysis of china’s green consumption policies: A quantitative analysis based on policy texts. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.; Li, H.; Ali, R.; Rehman, R.U. Knowledge mapping of corporate financial performance research: A visual analysis using citespace and ucinet. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurong, Z.; Kuan, J.; Qingshi, M. A research on china’s 5g policy characteristics and evolution trends based on multi-dimensional quantitative analysis of policy documents. Forum Sci. Technol. China 2022, 3, 125–137. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherven, K. Network Graph Analysis and Visualization with Gephi; Packt Publishing: Birmingham, UK, 2013; Volume 24. [Google Scholar]

- Gang, L.; Zhichao, B. Co-word analysis: Limitations and solutions. J. Libr. Sci. China 2017, 43, 93–113. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Mei, S. Visualizing the gvc research: A co-occurrence network based bibliometric analysis. Scientometrics 2016, 109, 953–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Zhang, H. Improving the co-word analysis method based on semantic distance. Scientometrics 2017, 111, 1521–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraji, O.; Asiaei, K.; Rezaee, Z.; Bontis, N.; Dolatzarei, E. Mapping the conceptual structure of intellectual capital research: A co-word analysis. J. Innov. Knowl. 2022, 7, 100202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; He, R.; Liu, J.; Li, C.; Xiong, J. Quantitative evaluation of china’s pork industry policy: A pmc index model approach. Agriculture 2021, 11, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.; Yao, N. Big data analytics, text mining and modern english language. J. Grid Comput. 2019, 17, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haibo, Q.; Wenhan, L.; Luling, S.; Lili, L.; Jie, L. Research on the focus change and evolution of china’s digital economy policy. Forum Sci. Technol. China 2024, 3, 83–94. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Cao, C. Historical transitions of seed breeding in china: From socialist cooperation to joint research. J. Rural Stud. 2025, 115, 103592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yi, Z.; Shang, H.; Liu, Z. Foreign bank entry and the outward foreign direct investment of companies: Evidence from china. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2024, 55, 896–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiaojiao, S.; Fang, X.; Wei, M. Changes and evolutions of science and technology evaluation policies in china: Characteristics, subjects and collaborative networks. Sci. Res. Manag. 2021, 42, 11. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Cao, C. The evolving relations between government agencies of innovation policymaking in emerging economies: A policy network approach and its application to the chinese case. Res. Policy 2018, 47, 592–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Jiang, L.; Cao, C. Multiple proximities and inter-agency collaboration within a policy network: The case of innovation policymaking in china. Technovation 2025, 141, 103169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raum, S.; Potter, C. Forestry paradigms and policy change: The evolution of forestry policy in britain in relation to the ecosystem approach. Land Use Policy 2015, 49, 462–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data Source | Nature | Link |

|---|---|---|

| PKULAW (Peking University Law Database) | Professional commercial legal database | https://www.pkulaw.com/law/?keyword= (accessed on 10 July 2024) |

| Official website of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs (MARA) | Portal of the leading governmental department for agricultural affairs | https://www.moa.gov.cn/ |

| Policy Document Database of the State Council | Official platform for central government policy releases | https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengcewenjianku/index.htm (accessed on 10 July 2024) |

| Official website of the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) | Portal of the relevant governmental authority for science and technology | https://www.most.gov.cn/index.html (accessed on 10 July 2024) |

| Variable | 2000–2010 | 2011–2020 | 2021–2024 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Co-authored Papers | 9 | 8 | 13 |

| Co-authored Papers/Total Policies | 39% | 19% | 43% |

| Number of Nodes | 4 | 9 | 20 |

| Average Degree | 1 | 3.78 | 4.6 |

| Average Weighted Degree | 4.5 | 5.78 | 8.7 |

| Network Density | 0.167 | 0.278 | 0.124 |

| Centrality Index | 0 | 0.357 | 0.608 |

| Keyword | Frequency | Centrality | Keyword | Frequency | Centrality | Keyword | Frequency | Centrality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seed | 18 | 33 | Breeding | 21 | 21 | Subsidy | 3 | 18 |

| Variety | 10 | 33 | Breeding and Selection | 21 | 21 | System | 4 | 17 |

| Promotion | 9 | 33 | Management | 21 | 21 | Project | 4 | 17 |

| Quality Seed | 13 | 30 | Construction | 21 | 21 | Inspection | 3 | 17 |

| Production | 8 | 29 | Support | 20 | 20 | Seed Industry | 5 | 16 |

| Quality | 5 | 29 | Aquaculture | 20 | 20 | Administration | 5 | 16 |

| Germplasm Resources | 7 | 25 | Plants and Animals | 20 | 20 | Enterprise | 3 | 15 |

| Crops | 5 | 25 | New Varieties | 19 | 19 | Seed Law | 3 | 15 |

| Technology | 3 | 24 | Standards | 18 | 18 | Cultivation | 3 | 15 |

| Base | 8 | 23 | Licenses | 18 | 18 | Market Access | 4 | 15 |

| Seed Projects | 8 | 23 | Approval | 18 | 18 | Law Enforcement | 3 | 13 |

| Livestock | 6 | 22 | Market Regulation | 18 | 18 |

| Keywords | Frequency | Centrality | Keywords | Frequency | Centrality | Keywords | Frequency | Centrality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seed Industry | 34 | 37 | Superior Varieties | 16 | 37 | Management | 7 | 24 |

| Modern Seed Industry | 24 | 37 | Seed Production | 15 | 36 | Public Welfare | 6 | 29 |

| Bases | 23 | 37 | Integration of Breeding, Propagation, and Promotion (IBPP) | 13 | 34 | Propagation | 6 | 27 |

| Germplasm Resources | 23 | 37 | Production | 12 | 29 | Seed Law | 6 | 26 |

| Varieties | 23 | 36 | Cultivation | 11 | 34 | Mechanism | 5 | 30 |

| Breeding | 23 | 36 | Protection | 11 | 28 | Technology | 5 | 29 |

| Seeds | 22 | 36 | System | 11 | 34 | Higher Education Institutions | 5 | 27 |

| Enterprises | 20 | 37 | Research Institutes | 10 | 34 | Talent | 4 | 27 |

| New Varieties | 19 | 37 | Collaborative Research | 9 | 31 | Scientific Research | 4 | 26 |

| Crops | 18 | 37 | Research Outcomes | 9 | 30 | Biological Breeding | 4 | 26 |

| Livestock and Poultry | 17 | 36 | Resources | 8 | 27 | Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs) | 4 | 26 |

| Innovation | 16 | 36 | Equity Distribution | 7 | 28 | Rule of Law in Seed Management | 4 | 22 |

| Development | 16 | 37 | Genetics | 7 | 26 |

| Keywords | Frequency | Centrality | Keywords | Frequency | Centrality | Keywords | Frequency | Centrality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seed Industry | 22 | 42 | Variety | 8 | 35 | Modern Seed Industry | 7 | 29 |

| Seed Industry Revitalization | 19 | 42 | Aquaculture | 6 | 35 | Conservation | 6 | 29 |

| Breeding | 17 | 42 | Core Technology | 6 | 34 | Science and Technology | 5 | 29 |

| Germplasm Resources | 16 | 41 | Construction | 6 | 34 | Combating Infringement | 5 | 29 |

| Livestock and Poultry | 13 | 41 | Crops | 5 | 34 | Leading Enterprises | 3 | 29 |

| Improved Varieties | 13 | 40 | Seeds | 7 | 33 | Precision | 5 | 27 |

| Base | 12 | 40 | Innovation | 6 | 33 | Mechanism | 5 | 26 |

| R&D | 7 | 40 | Promotion and Application | 6 | 33 | Service | 4 | 26 |

| Biological Breeding | 12 | 39 | Seed Sources | 6 | 33 | Major Projects | 4 | 25 |

| Tackling Key Issues | 9 | 39 | Supervision | 6 | 33 | New Varieties | 3 | 23 |

| Seed Production | 10 | 38 | Industrialization | 6 | 33 | Formation Enterprises | 3 | 22 |

| Propagation | 7 | 38 | Census | 5 | 32 | Talent | 3 | 21 |

| Resource Bank | 9 | 37 | Subsidy | 5 | 32 | New Variety Rights | 3 | 18 |

| Intellectual Property | 7 | 37 | Enterprises | 5 | 32 | |||

| Joint Tackling | 9 | 35 | Southern Breeding | 5 | 30 |

| Historical Stage | Policy Issues | Policy Objectives | Policy Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Adjustment Period (2000–2010) | Underdeveloped market mechanisms, inadequate seed market regulation, insufficient seed supply capacity | Reform and improve seed management systems, strengthen seed market regulation, enhance seed supply capacity | Market access, market regulation, legal frameworks, financial support including subsidies for elite varieties and major projects such as seed industry projects, infrastructure construction such as breeding bases and seed processing facilities |

| Deepening Adjustment Period (2011–2020) | Insufficient protection and utilization of germplasm resources, lagging biological breeding technologies domestically, underlying systemic issues within the seed industry | Deepen seed industry reform, strengthen germplasm resource protection and utilization, improve breeding innovation capabilities | Building research environment through R&D platforms, increased funding for biological breeding capacity development and industrialization projects, talent cultivation, infrastructure development including national germplasm resource bank, germplasm big data platforms, seed production bases; enhancing information services; offering tax incentives; protecting intellectual property; regulating through legal measures; developing markets |

| Comprehensive Adjustment Period (2021–2024) | Bottlenecks in seed sources, limited international competitiveness of seed enterprises, low level of intellectual property protection for breeding innovations | Achieve technological independence and self-reliance in the seed industry, maintain control and self-sufficiency over seed sources | Constructing innovation environment with platforms; increasing funding for major biological breeding projects, variety research, and promotion subsidies; supporting national seed industry large enterprises; infrastructure development including seed industry innovation bases and core breeding bases; talent cultivation; information services; tax incentives; strengthening intellectual property protections including establishing substantive derivative variety systems; financial services; regulatory measures; market regulation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hu, S.; Xiong, C.; Jiang, D. Enhancing the Marketization and Globalization Response Capacity of Policies: Evolution of China’s Seed Industry Policies Since the 21st Century. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2383. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15222383

Hu S, Xiong C, Jiang D. Enhancing the Marketization and Globalization Response Capacity of Policies: Evolution of China’s Seed Industry Policies Since the 21st Century. Agriculture. 2025; 15(22):2383. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15222383

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Siqi, Chunlin Xiong, and Duo Jiang. 2025. "Enhancing the Marketization and Globalization Response Capacity of Policies: Evolution of China’s Seed Industry Policies Since the 21st Century" Agriculture 15, no. 22: 2383. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15222383

APA StyleHu, S., Xiong, C., & Jiang, D. (2025). Enhancing the Marketization and Globalization Response Capacity of Policies: Evolution of China’s Seed Industry Policies Since the 21st Century. Agriculture, 15(22), 2383. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15222383