Mechanistic Insights into the Differential Effects of Biochar and Organic Fertilizer on Nitrogen Loss Pathways in Vegetable Soils: Linking Soil Carbon, Aggregate Stability, and Denitrifying Microbes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site

2.2. Test Materials

2.3. Experimental Design

2.4. Sample Collection

2.5. Sample Determination

2.6. Soil DNA Extraction and Real Time PCR Analysis

2.7. High-Throughput Sequencing of Bacterial 16 S rRNA Gene and Bioinformatic Analysis

2.8. Calculation Parameters

2.9. Data and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Biochar and Organic Fertilizer Application on the Proportion of Nitrogen Fate

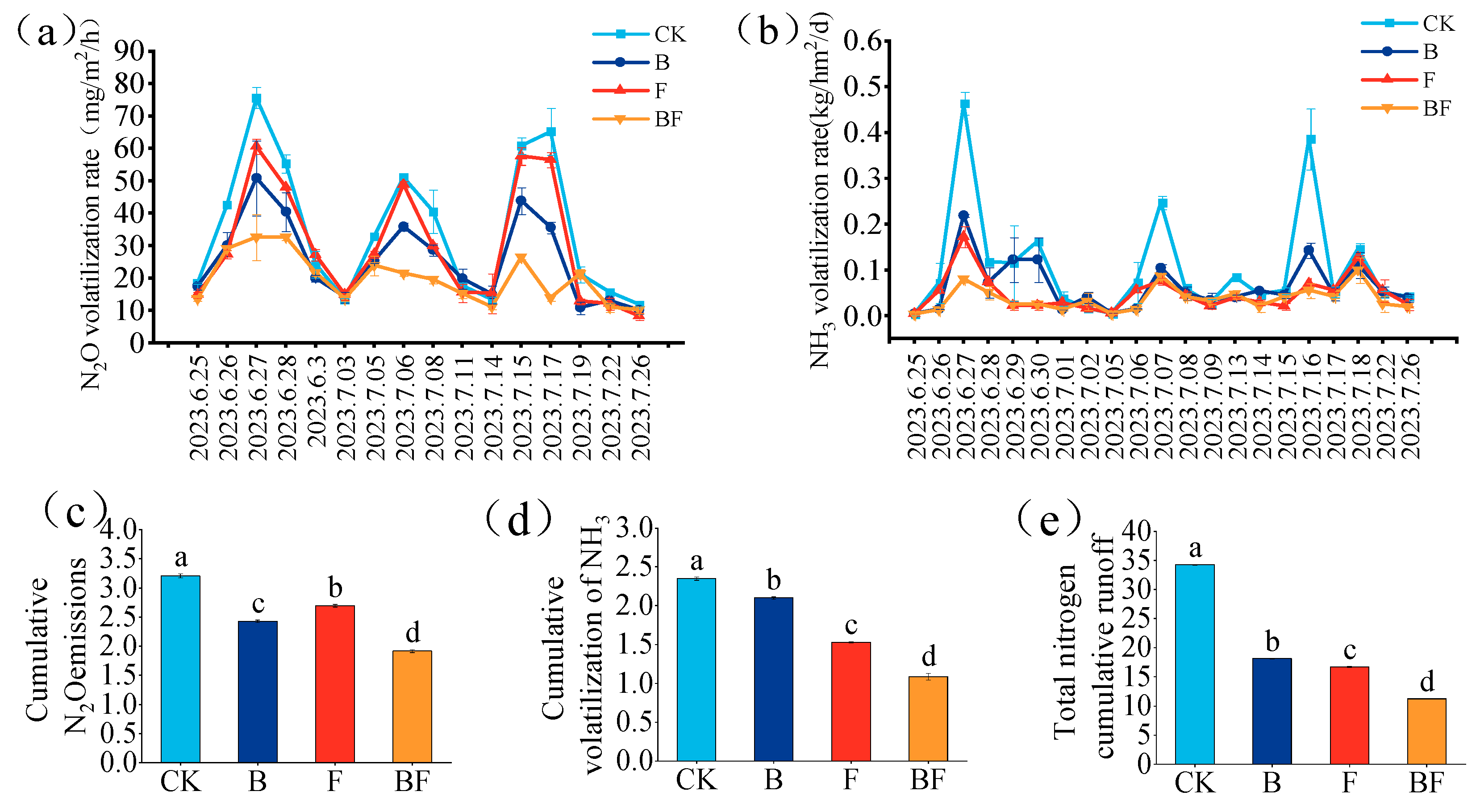

3.2. Effects of Biochar and Organic Fertilizer on N Loss Characteristics

3.3. Effects of Biochar and Organic Fertilizer on Soil Organic Carbon Fractions

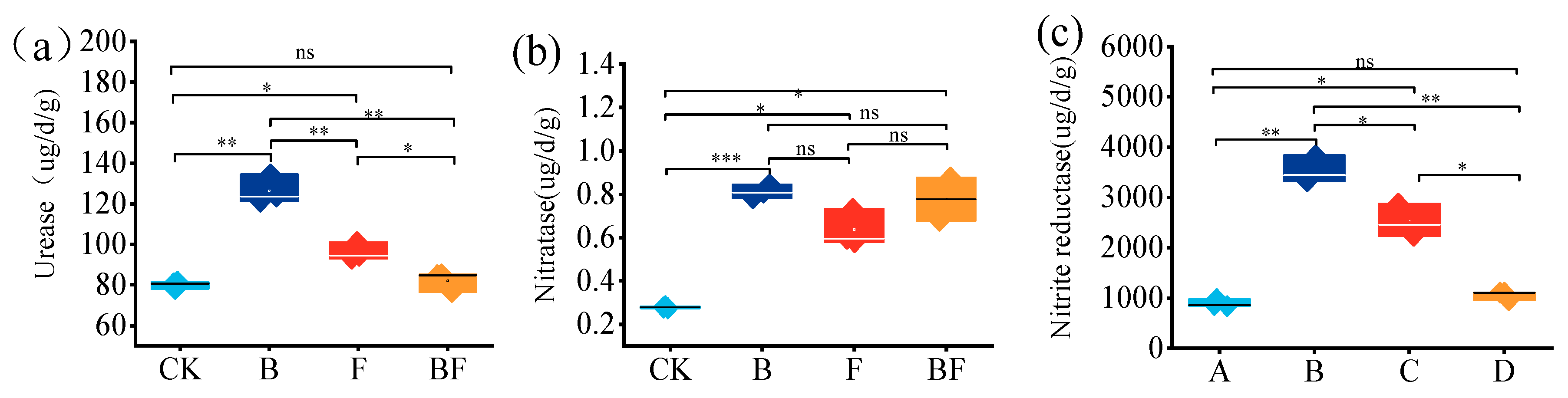

3.4. Effects of Biochar and Organic Fertilizer on Soil Enzyme Activities

3.5. Effects of Biochar and Organic Fertilizer on Soil Physical and Chemical Properties

3.6. Effects of Biochar and Organic Fertilizer Application on Soil Nitrogen Forms

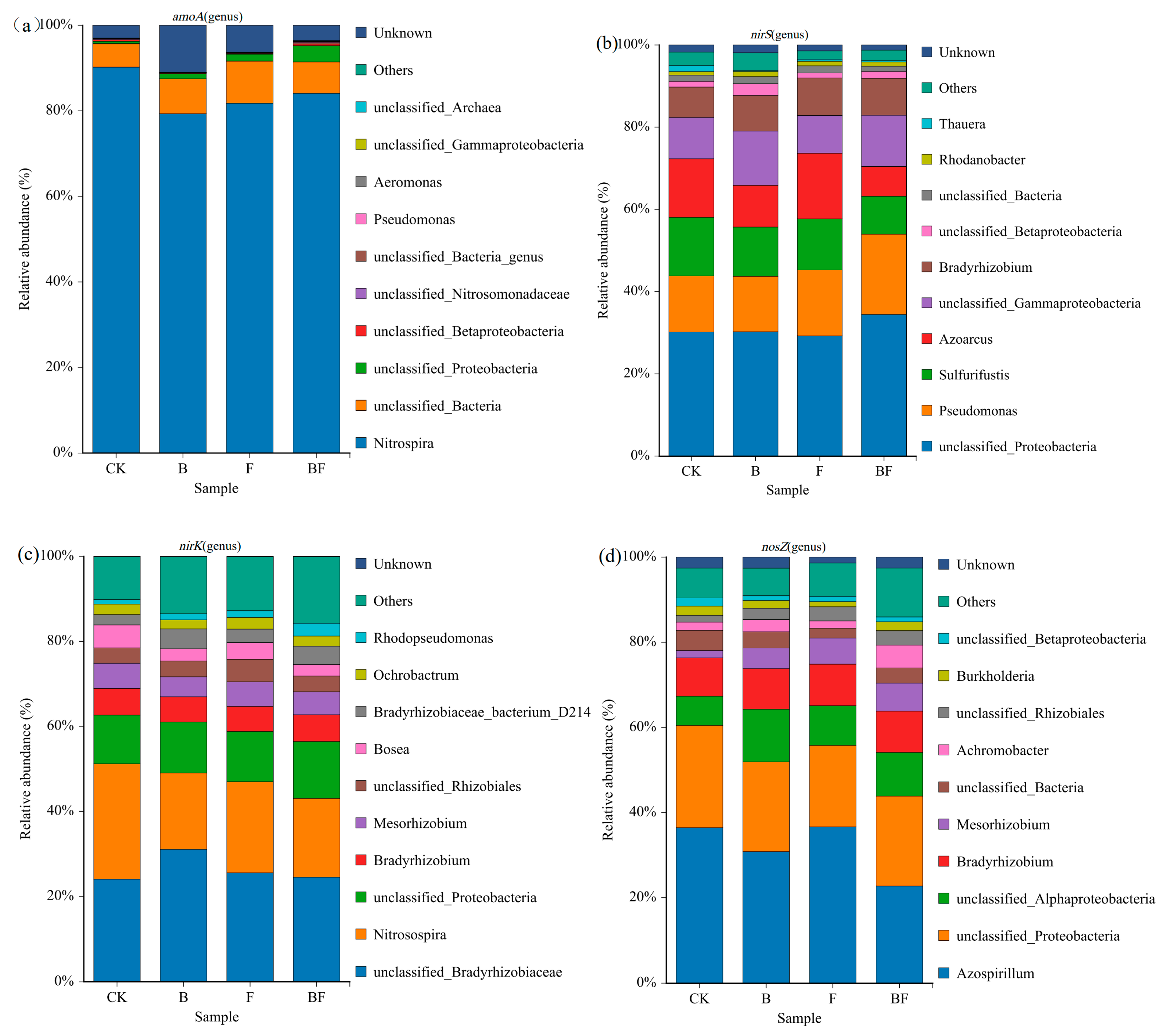

3.7. Effects of Biochar and Organic Fertilizer Application on Key Microbial Communities of Soil Nitrogen Transformation

3.8. Correlation Analysis and Structural Equation Model of Nitrogen Runoff Loss and NH3 Volatilization Under Biochar and Organic Fertilizer Application

3.9. Analysis of Soil Nitrogen-Transforming Microbial COMMUNITIES and Key Predictors of N2O Emissions

4. Discussion

4.1. The Influence of Applying Biochar and Organic Fertilizer on the Destination of Nitrogen

4.2. Effects of Biochar and Organic Fertilizer on Soil Organic Carbon Fractions

4.3. Effects of Biochar and Organic Fertilizer Application on Soil Physical and Chemical Properties

4.4. Effects of Biochar and Organic Fertilizer Application on Microbial Community

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fan, C.; Leng, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Fu, Y.; Huang, X.; Gao, W.; Zhang, W.; Liu, H.; Ning, Z.; et al. Enhanced mitigation of N2O and NO emissions through co-application of biochar with nitrapyrin in an intensive tropical vegetable field. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 365, 108910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, S.; Nayak, A.K.; Swain, C.K.; Dhal, B.R.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, U.; Tripathi, R.; Shahid, M.; Behera, K.K. Impact of integrated nutrient management options on GHG emission, N loss and N use efficiency of low land rice. Soil Tillage Res. 2020, 200, 104616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Gao, X.; Wang, F.; Xu, G.; Long, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, Z.; Gao, M. Effects of biochar incorporation and fertilizations on nitrogen and phosphorus losses through surface and subsurface flows in a sloping farmland of Entisol. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 300, 106988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Zhang, G.; Xie, H.; Chang, N.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, G.; Li, H. Balancing high yields and low N2O emissions from greenhouse vegetable fields with large water and fertilizer input: A case study of multiple-year irrigation and nitrogen fertilizer regimes. Plant Soil 2023, 483, 131–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Kang, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Cardenas, L.M.; Chen, Q. Is sorghum a promising summer catch crop for reducing nitrate accumulation and enhancing eggplant yield in intensive greenhouse vegetable systems? Plant Soil 2024, 499, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beillouin, D.; Corbeels, M.; Demenois, J.; Berre, D.; Boyer, A.; Fallot, A.; Feder, F.; Cardinael, R. A global meta-analysis of soil organic carbon in the Anthropocene. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.Y.; Jing, Y.M.; Chen, C.R.; Xiang, Y.Z.; Rashti, M.R.; Li, Y.T.; Deng, Q.; Zhang, R.D. Effects of biochar application on soil nitrogen transformation, microbial functional genes, enzyme activity, and plant nitrogen uptake: A meta-analysis of field studies. Gcb Bioenergy 2021, 13, 1859–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, P.; Chen, Z.; Wang, H.; Lv, R.; Hu, T.; Zhou, R.; Zhang, J.; Lin, X.; Liu, Q.; Xie, Z. 12-year continuous biochar application: Mitigating reactive nitrogen loss in paddy fields but without rice yield enhancement. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 375, 109223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Cui, J.; Zhang, M.; Liu, J.; Wang, L.; Zhao, J.; Bao, Z. Diversity of active anaerobic ammonium oxidation (ANAMMOX) and nirK-type denitrifying bacteria in macrophyte roots in a eutrophic wetland. J. Soils Sediments 2021, 21, 2465–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Jiang, M.H.; Ding, K.R.; Zhou, S.G. Iron oxides affect denitrifying bacterial communities with the nirS and nirK genes and potential N2O emission rates from paddy soil. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2019, 93, 103093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.G.; Rasmann, S.; Yue, L.; Lian, F.; Zou, H.; Wang, Z.Y. The effect of biochar amendment on N-cycling genes in soils: A meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 696, 133984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, D.C.; Su, X.Y.; Xie, H.T.; Bao, X.L.; Zhang, X.D.; Wang, L.F. Effects of tillage patterns and stover mulching on N2O production, nitrogen cycling genes and microbial dynamics in black soil. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hei, Z.W.; Peng, Y.T.; Hao, S.L.; Li, Y.M.; Yang, X.; Zhu, T.B.; Müller, C.; Zhang, H.Y.; Hu, H.W.; Chen, Y.L. Full substitution of chemical fertilizer by organic manure decreases soil N2O emissions driven by ammonia oxidizers and gross nitrogen transformations. Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 29, 7117–7130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.L.; Wen, X.L.; Yang, H.M.; Lu, H.; Wang, A.; Liu, S.P.; Li, Q.L. Incorporating microbial inoculants to reduce nitrogen loss during sludge composting by suppressing denitrification and promoting ammonia assimilation. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 915, 170000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Jiang, Z.Q.; Ou, J.M.; Liu, F.D.; Cai, G.Y.; Tan, K.M.; Wang, X.L. Nitrogen substitution practice improves soil quality of red soil (Ultisols) in South China by affecting soil properties and microbial community composition. Soil Tillage Res. 2024, 240, 106089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Götze, H.; Buchen-Tschiskale, C.; Eder, L.; Pacholski, A. Effects of inhibitors and slit incorporation on NH3 and N2O emission processes after urea application. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, 378, 109307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.L.; Zhao, Q.; Lin, G.G.; Hong, X.; Zeng, D.H. Nitrogen addition impacts on soil phosphorus transformations depending upon its influences on soil organic carbon and microbial biomass in temperate larch forests across northern China. Catena 2023, 230, 107252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.X.; Peng, Y.Y.; Li, M.Y.; Li, X.; Li, H.Y.; Dabu, X.; Yang, Y. Different active exogenous carbons improve the yield and quality of roses by shaping different bacterial communities. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1558322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, C.R.; Peng, Y.; Zeng, M.; Dabu, X. Effects of biochar and organic fertilizer application on physical and chemical properties of red soil and nitrogen losses by runoff. Soil Fertil. Sci. China 2023, 4, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.L.; Zhang, Y.; Ji, C.F.; Luo, X.S.; Li, T.K.; Xiao, Q.; Dong, W.X. Influence of the combination of wheat straw to straw biochar on N2Ogas emissions from calcareous fluvo-aquic soil. J. Agric. Resour. Environ. 2025, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, P.; Zhang, J.; Shen, J.L.; Zhu, X.; Wang, W.; Wang, J.; Wu, J.S. Effects of combined application of organic and chemical fertilizers on N2O emission and NH3 volatilization in protected vegetable soils. Res. Agric. Mod. 2023, 44, 701–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhao, X.Y.; Yi, G.R.; Zhang, W.Q.; Gao, R.Y.; Tang, D.K.H.; Xiao, R.; Zhang, Z.Q.; Yao, Y.Q.; Li, R.H. Promoting nitrogen conversion in aerobic biotransformation of swine slurry with the co-application of manganese sulfate and biochar. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 356, 120604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Dabu, X.; Yang, Y.; Li, C.; Huang, J.L. Effect of Biochar and Organic FertilizerApplication on Nitrogen Loss in Gaseous State in Newly Reclaimed Red Soil. Chin. J. Soil Sci. 2024, 55, 1366–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herlemann, D.P.; Labrenz, M.; Jürgens, K.; Bertilsson, S.; Waniek, J.J.; Andersson, A.F. Transitions in bacterial communities along the 2000 km salinity gradient of the Baltic Sea. ISME J. 2011, 5, 1571–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caporaso, J.G.; Kuczynski, J.; Stombaugh, J.; Bittinger, K.; Bushman, F.D.; Costello, E.K.; Fierer, N.; Peña, A.G.; Goodrich, J.K.; Gordon, J.I.; et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods 2010, 7, 335–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Nei, M.; Dudley, J.; Tamura, K. MEGA: A biologist-centric software for evolutionary analysis of DNA and protein sequences. Brief. Bioinform. 2008, 9, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.Y.; Feng, Y.F.; Liu, Q.; Chen, S.; Hou, P.F.; Poinern, G.; Jiang, Z.T.; Fawcett, D.; Xue, L.H.; Lam, S.S.; et al. How does biochar aging affect NH3 volatilization and GHGs emissions from agricultural soils? Environ. Pollut. 2022, 294, 118598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Liang, F.; Wu, Q.; Feng, X.G.; Shang, W.D.; Li, H.W.; Li, X.X.; Che, Z.; Dong, Z.R.; Song, H. Soil pH differently affects N2O emissions from soils amended with chemical fertilizer and manure by modifying nitrification and denitrification in wheat-maize rotation system. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2024, 60, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davys, D.; Rayns, F.; Charlesworth, S.; Lillywhite, R. The effect of different biochar characteristics on soil nitrogen transformation processes: A review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.H.; El-Sawah, A.M.; Ali, D.F.I.; Hamoud, Y.A.; Shaghaleh, H.; Sheteiwy, M.S. The integration of bio and organic fertilizers improve plant growth, grain yield, quality and metabolism of hybrid maize (Zea mays L.). Agronomy 2020, 10, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.L.; Liu, X.R.; Zhang, Q.W. Effects of combined biochar and organic fertilizer on nitrous oxide fluxes and the related nitrifier and denitrifier communities in a saline-alkali soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 686, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagas, J.K.M.; Nardoto, G.B.; Madari, B.E.; de Figueiredo, C.C. Seven-year effects of sewage sludge biochar on soil organic carbon pools and yield: Understanding the role of biochar on carbon sequestration and productivity. Soil Use Manag. 2024, 40, e70001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, M.; Choudhary, P.; Choudhary, M.; Srinivasan, R.; Kumar, A.; Mahawer, S.K.; Kumar, A.; Palsaniya, D.R.; Kumar, S. Application of Invasive Weed Biochar as Soil Amendment Improves Soil Organic Carbon Fractions and Yield of Fodder Oat in a Semi-Arid Region. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 24, 2111–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Lu, J.; Feng, H.; Chen, J.; Yang, Q.; Zhou, L.; Li, N.; Siddique, K.H.; Liang, J. Soil extracellular enzymes, soil carbon and nitrogen storage under straw return: A data synthesis. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 228, 120884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, R.; Cai, Y.; Li, J.; Kong, Y.; Jiang, T.; Chang, J.; Yao, S.; Yuan, J.; Li, G.; Wang, G. Biochar reduces gaseous emissions during poultry manure composting: Evidence from the evolution of associated functional genes. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 452, 142060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tian, Z.; Li, X.; Zhang, M.; Fang, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, E.; Jia, Z.; Siddique, K.H.; et al. Straw-derived biochar regulates soil enzyme activities, reduces greenhouse gas emissions, and enhances carbon accumulation in farmland under mulching. Field Crops Res. 2024, 317, 109547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokol, N.W.; Slessarev, E.; Marschmann, G.L.; Nicolas, A.; Blazewicz, S.J.; Brodie, E.L.; Firestone, M.K.; Foley, M.M.; Hestrin, R.; Hungate, B.A.; et al. Life and death in the soil microbiome: How ecological processes influence biogeochemistry. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 20, 415–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Su, X.; Wen, T.; McBratney, A.B.; Zhou, S.; Huang, F.; Zhu, Y.G. Soil properties shape the heterogeneity of denitrification and N2O emissions across large-scale flooded paddy soils. Glob. Change Biol. 2024, 30, e17176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Wang, J.; Riaz, M.; Babar, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Xia, X.; Liu, B.; Jiang, C. Co-application of biochar and potassium fertilizer improves soil potassium availability and microbial utilization of organic carbon: A four-year study. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 469, 143211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippon, T.; Tian, J.; Bureau, C.; Chaumont, C.; Midoux, C.; Tournebize, J.; Bouchez, T.; Barrière, F. Denitrifying bio-cathodes developed from constructed wetland sediments exhibit electroactive nitrate reducing biofilms dominated by the genera Azoarcus and Pontibacter. Bioelectrochemistry 2021, 140, 107819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Z.; Sun, R.; Wu, Y.; Hu, S.; Liu, X.; Chan, J.; Mi, X. Characteristics and metabolic pathway of the bacteria for heterotrophic nitrification and aerobic denitrification in aquatic ecosystems. Environ. Res. 2020, 191, 110069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | Gaseous Loss Rate | Runoff Loss Rate | Plant Absorption Rate | Soil Residual Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | 2.32–5.57 | 13.92–28.96 | 26.20–45.43 | 36.88–46.15 |

| B | 1.72–4.28 | 8.06–24.25 | 42.02–69.95 | 19.98–33.99 |

| F | 1.65–4.13 | 6.72–29.16 | 34.01–50.26 | 32.70–40.43 |

| BF | 1.33–3.81 | 4.60–29.38 | 42.66–72.00 | 21.67–34.558 |

| Treatment | SOC (g/kg) | ROC (g/kg) | IOCS (g/kg) | DOC (mg/kg) | MBC (mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | 3.07 ± 0.08 c | 1.79 ± 0.03 c | 1.63 ± 0.65 b | 27.59 ± 1.87 c | 88.98 ± 1.68 c |

| B | 7.47 ± 0.22 a | 2.35 ± 0.07 b | 4.92 ± 0.75 a | 34.14 ± 0.94 c | 108.93 ± 4.94 b |

| F | 6.39 ± 0.03 b | 2.53 ± 0.01 ab | 3.83 ± 0.34 a | 61.73 ± 2.43 a | 135.56 ± 3.56 a |

| BF | 6.10 ± 0.01 b | 2.85 ± 0.27 a | 5.03 ± 0.74 a | 49.11 ± 2.81 b | 114.58 ± 8.08 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, S.; Hu, L.; Ma, C.; Li, M.; Peng, Y.; Peng, Y.; Dabu, X.; Huang, J. Mechanistic Insights into the Differential Effects of Biochar and Organic Fertilizer on Nitrogen Loss Pathways in Vegetable Soils: Linking Soil Carbon, Aggregate Stability, and Denitrifying Microbes. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2326. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15222326

Li S, Hu L, Ma C, Li M, Peng Y, Peng Y, Dabu X, Huang J. Mechanistic Insights into the Differential Effects of Biochar and Organic Fertilizer on Nitrogen Loss Pathways in Vegetable Soils: Linking Soil Carbon, Aggregate Stability, and Denitrifying Microbes. Agriculture. 2025; 15(22):2326. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15222326

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Shixiong, Linsong Hu, Chun Ma, Manying Li, Yuanyang Peng, Yin Peng, Xilatu Dabu, and Jiangling Huang. 2025. "Mechanistic Insights into the Differential Effects of Biochar and Organic Fertilizer on Nitrogen Loss Pathways in Vegetable Soils: Linking Soil Carbon, Aggregate Stability, and Denitrifying Microbes" Agriculture 15, no. 22: 2326. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15222326

APA StyleLi, S., Hu, L., Ma, C., Li, M., Peng, Y., Peng, Y., Dabu, X., & Huang, J. (2025). Mechanistic Insights into the Differential Effects of Biochar and Organic Fertilizer on Nitrogen Loss Pathways in Vegetable Soils: Linking Soil Carbon, Aggregate Stability, and Denitrifying Microbes. Agriculture, 15(22), 2326. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15222326