UAV-Based Multimodal Monitoring of Tea Anthracnose with Temporal Standardization

Abstract

1. Introduction

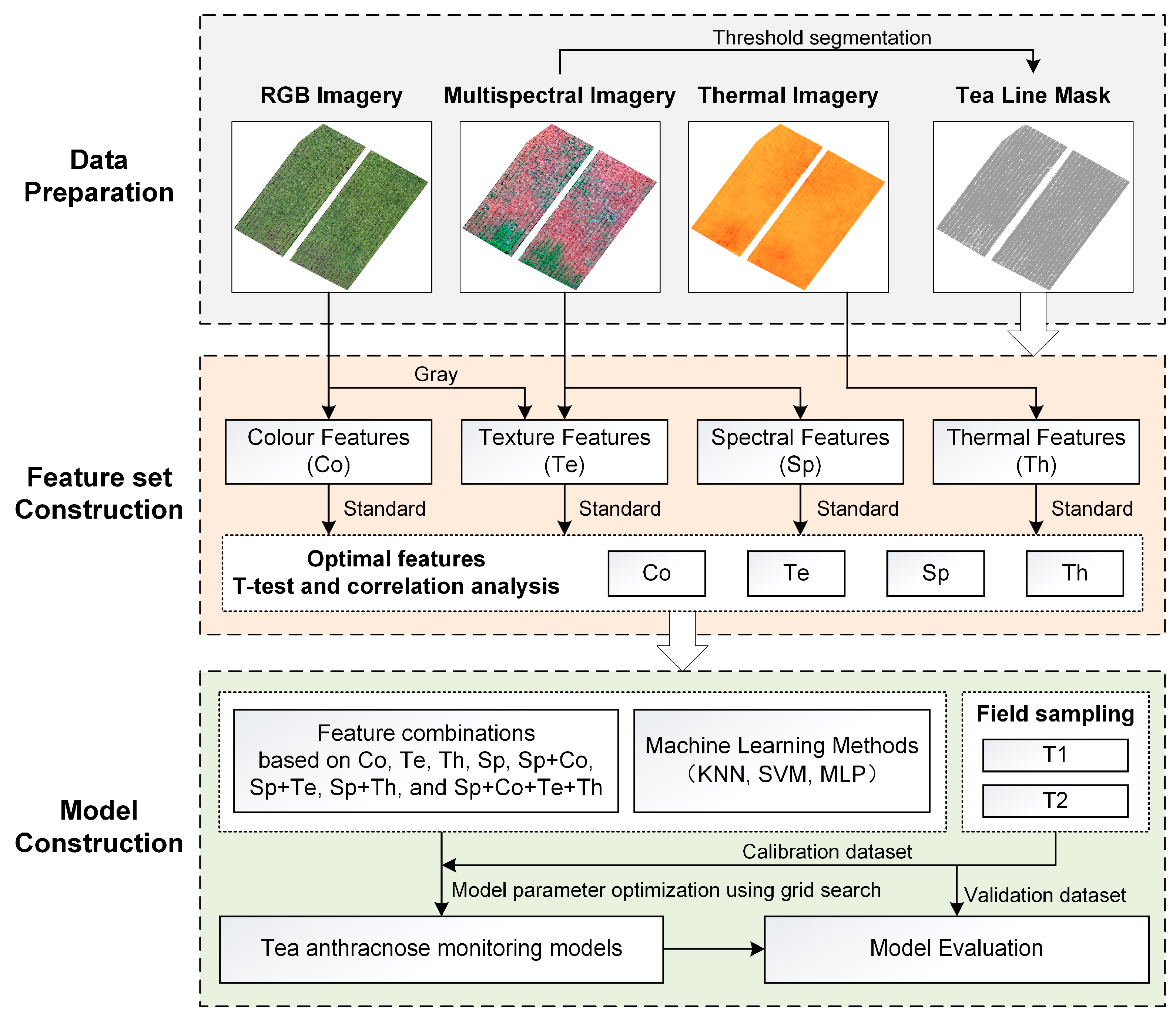

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Ground Data Acquisition

2.3. UAV Multi-Source Image Acquisition and Preprocessing

2.4. Data Analysis

2.4.1. Spectral, Color, Texture, and Thermal Feature Extraction for Tea Plantations

| Kind | Features | Formulation | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sp | Green(G), Red(R), Red Edge(RE), Near Infrared(NIR) | Original reflectance of each band | / |

| Wide dynamic range vegetation index (WDRVI) | (0.1 × NIR − R)/(0.1 × NIR + R) | [30] | |

| Visible Atmospherically Resistant Index for green band (VARIG) | (G − R)/(G + R) | [31] | |

| Simple Ratio (SR) | NIR/R | [32] | |

| Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Index (SAVI) | 1.5 × [(NIR − R)/(NIR + R + 0.5) | [33] | |

| Two-Band Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI2) | 2.5 × (NIR − R)/(NIR + 2.4 × R + 1) | [34] | |

| Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) | (NIR − R)/(NIR + R) | [35] | |

| Normalized Difference Red Edge (NDRE) | (NIR − RE)/(NIR + RE) | [36] | |

| Chlorophyll Index Green (CIG) | NIR/G − 1 | [37] | |

| Carotenoid Index (CARI) | RE/G − 1 | [38] | |

| Anthocyanin Reflectance Index (ARI) | 1/G − 1/RE | [39] | |

| Difference Vegetation Index (DVI) | NIR − R | [40] | |

| Green Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (GNDVI) | (NIR − G)/(NIR + G) | [41] | |

| Modified Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Index (MSAVI) | 1/2 × [(2NIR + 1) − ((2NIR + 1)2 – 8 × (NIR − R))1/2] | [42] | |

| Modified Simple Ratio (MSR) | (NIR/R − 1)/((NIR/R + 1)1/2) | [43] | |

| Optimized Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index (OSAVI) | (NIR − R)/(NIR + R + 0.16) | [44] | |

| Normalized Red-RE (NormRRE) | RE/(NIR + RE + G) | [45] | |

| Difference Vegetation Index-Rededge (DVIRE) | NIR − RE | [45] | |

| Co | r, g, b | Normalized Values of Each RGB Channel | / |

| Color Index of Vegetation (CIVE) | 0.441 × r − 0.811 × g + 0.385 × b + 18.78745 | [46] | |

| Excess green index (ExG) | 2 × g – r − b | [47] | |

| Excess red index (ExR) | 1.4 × r − g | [48] | |

| Excess green minus excess red index (ExGR) | (2 × g − r − b) − (1.4 × r − g) | [48] | |

| Green leaf index (GLI) | (2 × g − r − b)/(2 × g + r + b) | [49] | |

| Modified green-red vegetation index (MGRVI) | (g2 − r2)/(g2 + r2) | [50] | |

| Normalized green minus red difference index (NGRDI) | (g − r)/(g + r) | [51] | |

| Red-green-blue vegetation index (RGBVI) | (g2 – b × r)/(g2 + b × r) | [50] | |

| Normalized green minus blue difference index (NGBDI) | (g − b)/(g + b) | [52] | |

| Te | NDTI | (TP1 − TP2)/(TP1 + TP2) | / |

| DTI | TP1 − TP2 | / | |

| RTI | TP1/TP2 | / | |

| Th | Normalized relative canopy temperature (NRCT) | (T − Tmin)/(Tmax − Tmin) | [29] |

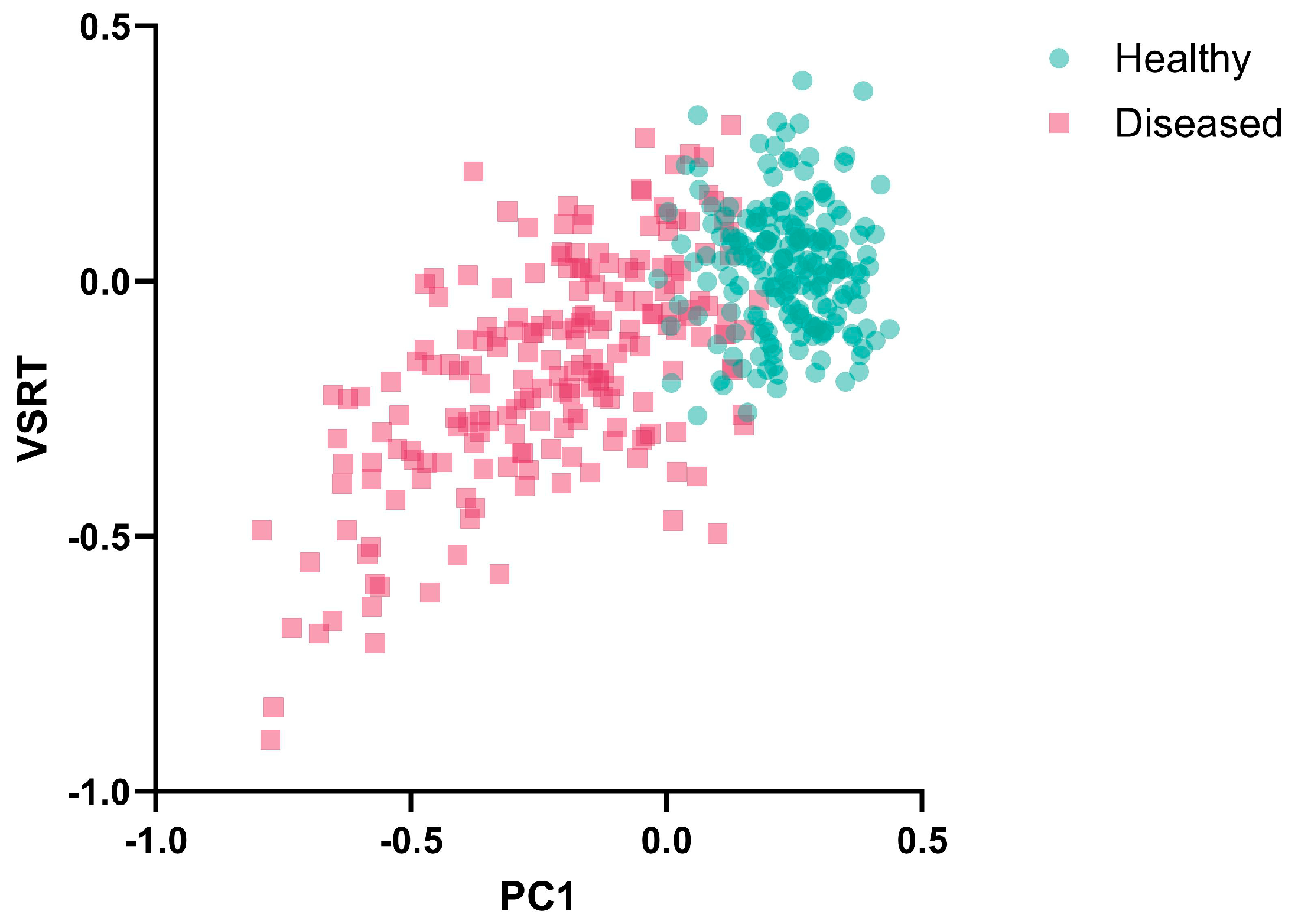

| Vegetation soil relative temperature (VSRT) | (Tc − Ts)/Ts | This Paper |

| Sensors | Bands | Texture Parameters | Texture Indices |

|---|---|---|---|

| MS | Green, Red, RedEdge, NIR | ME, VAR, HOM, CON, DIS, ENT, SEC, COR | NDTI, DTI, RTI |

| RGB | Gray | ME, VAR, HOM, CON, DIS, ENT, SEC, COR | NDTI, DTI, RTI |

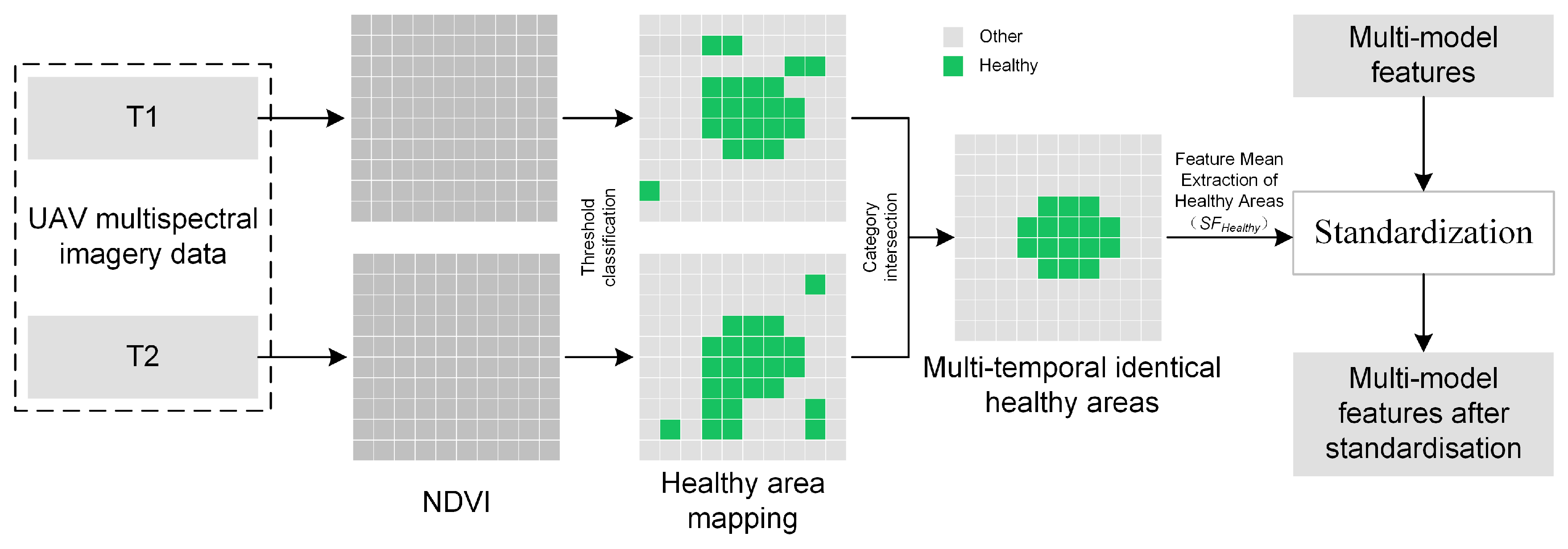

2.4.2. Relative-Difference Standardization of UAV Multimodal Data

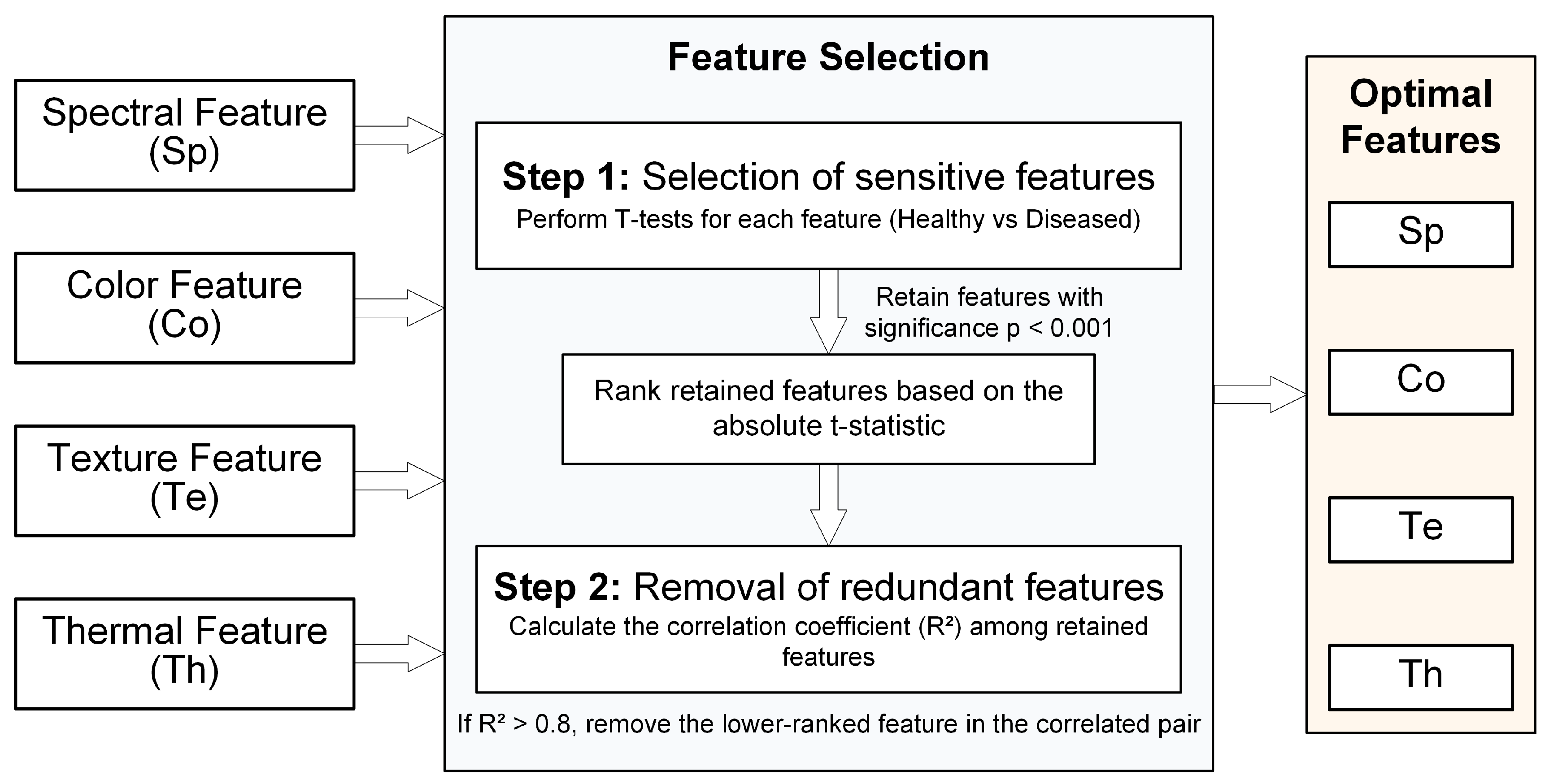

2.4.3. Optimal Selection of UAV Multi-Source Features

2.4.4. Construction of a Cross-Temporal General Monitoring Model for Tea Anthracnose

3. Results

3.1. Temporal Consistency Analysis of Multi-Source Features

3.2. Optimal Selection of a Multi-Source Sensitive Feature Set for Tea Anthracnose

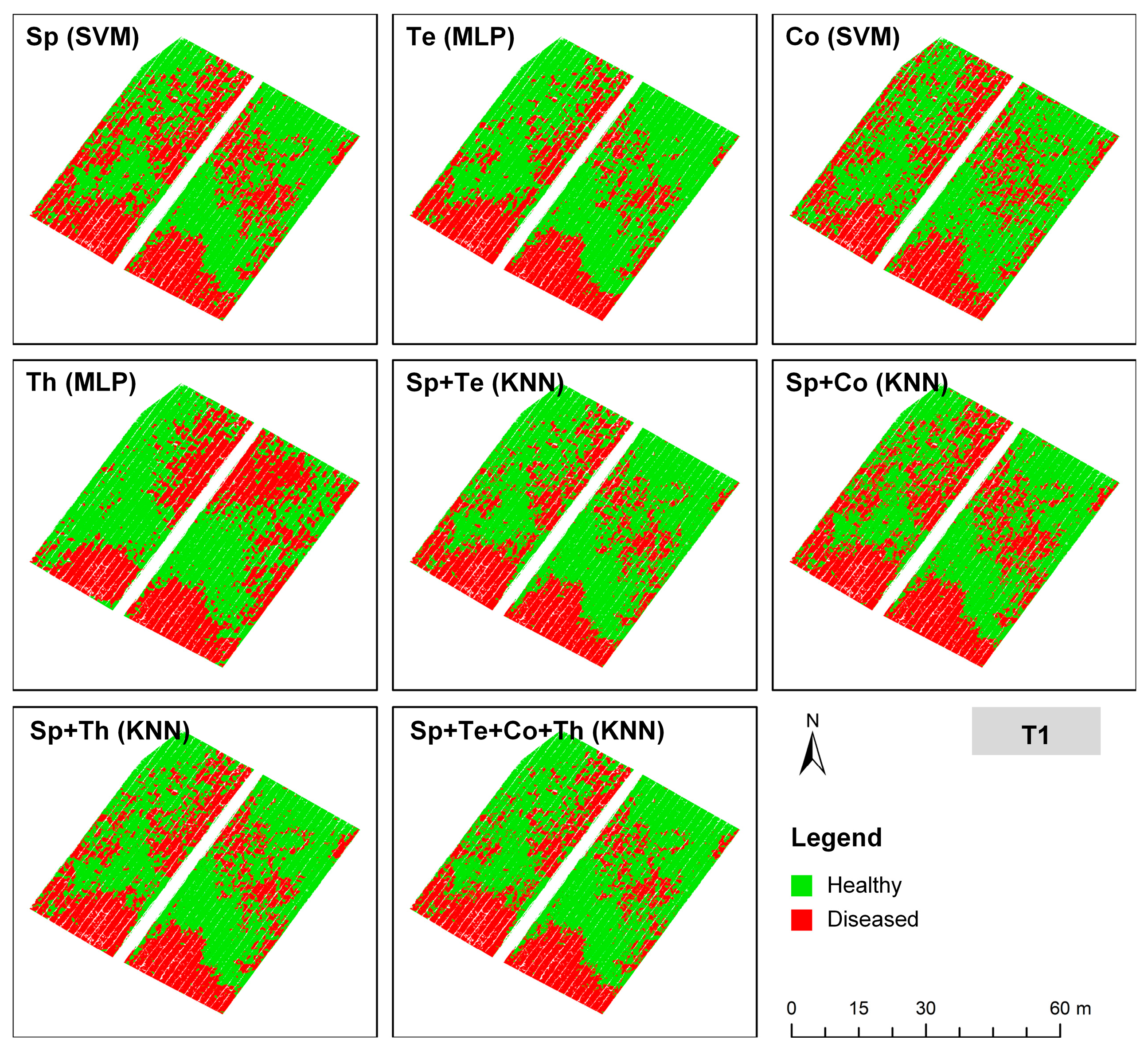

3.3. Comparison of Models That Combine Multi-Source Features with Different Algorithms

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- A relative-difference standardization strategy that uses NDVI identified healthy regions as the reference was proposed and validated, which effectively addressed feature inconsistencies among remote sensing data acquired at different times. Meanwhile, we constructed the innovative VSRT index, which exhibited higher temporal consistency and robustness compared to the Normalized Relative Canopy Temperature (NRCT).

- (2)

- A multimodal feature set was constructed using seven spectral features (SR, NIR, NormRRE, VARI_Green, Red, RedEdge, ARI), six texture features (NIR_D[MEA,HOM], NIR_R[SEC,MEA], RedEdge_N[MEA,SEC], Gray_R[MEA,DIS], Gray_D[MEA,DIS], Gray_N[VAR,DIS]), four color features (ExR, R, ExG, B), and one thermal feature (VSRT).

- (3)

- Among all model configurations, the multimodal combination of spectral and thermal features (‘Sp + Th’) integrated with the K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN) algorithm achieved the highest classification accuracy of 95.51%, confirming its superior capability for tea anthracnose detection and generalization.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Orrock, J.M.; Rathinasabapathi, B.; Spakes Richter, B. Anthracnose in U.S. Tea: Pathogen Characterization and Susceptibility Among Six Tea Accessions. Plant Dis. 2020, 104, 1055–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhong, L.; Zhang, Z.; Peng, C.; Ke, D.; Gan, P.; Wang, Z.; Wei, R.; Liu, W.; Yang, J. Isolation and Identification of Colletotrichum as Fungal Pathogen from Tea and Preliminary Fungicide Screening. Qual. Assur. Saf. Crops Foods 2022, 14, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Chen, H.; Wei, Y.; An, T.; Liu, S. Development of a DNA-Based Real-Time PCR Assay for the Quantification of Colletotrichum Camelliae Growth in Tea (Camellia sinensis). Plant Methods 2020, 16, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, A.K.; Sinniah, G.D.; Babu, A.; Tanti, A. How the Global Tea Industry Copes with Fungal Diseases—Challenges and Opportunities. Plant Dis. 2021, 105, 1868–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, W.; Zhu, Z.; Hu, G.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, D.; Yang, X. UAV Remote Sensing Detection of Tea Leaf Blight Based on DDMA-YOLO. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 205, 107637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phang, S.K.; Chiang, T.H.A.; Happonen, A.; Chang, M.M.L. From Satellite to UAV-Based Remote Sensing: A Review on Precision Agriculture. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 127057–127076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Vanhard, E.; Corpetti, T.; Houet, T. UAV & Satellite Synergies for Optical Remote Sensing Applications: A Literature Review. Sci. Remote Sens. 2021, 3, 100019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; He, J.; Yu, M.; Su, X.; Wang, X.; Zheng, H.; Yao, X.; Cheng, T.; Zhu, Y.; Cao, W.; et al. Multisource Remote Sensing Data-Driven Estimation of Rice Grain Starch Accumulation: Leveraging Matter Accumulation and Translocation Characteristics. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 4416818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakhvashvili, E.; Machwitz, M.; Antala, M.; Rozenstein, O.; Prikaziuk, E.; Schlerf, M.; Naethe, P.; Wan, Q.; Komárek, J.; Klouek, T.; et al. Crop Stress Detection from UAVs: Best Practices and Lessons Learned for Exploiting Sensor Synergies. Precis. Agric. 2024, 25, 2614–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, M.; Ibrahim, A.M.H.; Xue, Q.; Jung, J.; Chang, A.; Rudd, J.C.; Maeda, M.; Rajan, N.; Neely, H.; Landivar, J. Assessing Winter Wheat Foliage Disease Severity Using Aerial Imagery Acquired from Small Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV). Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 176, 105665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Liu, C.; Coombes, M.; Hu, X.; Wang, C.; Xu, X.; Li, Q.; Guo, L.; Chen, W. Wheat Yellow Rust Monitoring by Learning from Multispectral UAV Aerial Imagery. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 155, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulridha, J.; Ampatzidis, Y.; Kakarla, S.C.; Roberts, P. Detection of Target Spot and Bacterial Spot Diseases in Tomato Using UAV-Based and Benchtop-Based Hyperspectral Imaging Techniques. Precis. Agric. 2020, 21, 955–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Lu, Y.; Liang, H.; Lu, Z.; Yu, L.; Liu, Q. Areca Yellow Leaf Disease Severity Monitoring Using UAV-Based Multispectral and Thermal Infrared Imagery. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Ji, H.; Zhou, G.; Pan, R.; Zhao, L.; Duan, Z.; Liu, X.; Yin, J.; Duan, Y.; Ma, Y.; et al. Non-Destructive Monitoring of Tea Plant Growth through UAV Spectral Imagery and Meteorological Data Using Machine Learning and Parameter Optimization Algorithms. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 229, 109795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, M.M.; Tarshish, R.; Tubul, Y.; Sabag, I.; Gadri, Y.; Morota, G.; Peleg, Z.; Alchanatis, V.; Herrmann, I. Multimodal Ensemble of UAV-Borne Hyperspectral, Thermal, and RGB Imagery to Identify Combined Nitrogen and Water Deficiencies in Field-Grown Sesame. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2025, 222, 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Liu, X.; Wu, Q.; Liu, M.; Hu, X.; Deng, H.; Zhang, Y.; Qu, Y.; Wang, B.; Gou, X.; et al. Utilizing UAV-Based High-Throughput Phenotyping and Machine Learning to Evaluate Drought Resistance in Wheat Germplasm. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 237, 110602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, X.; Bai, T.; Yuan, X.; Bao, H.; He, D.; Sun, W.; He, Y. Cotton Verticillium Wilt Monitoring Based on UAV Multispectral-Visible Multi-Source Feature Fusion. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 217, 108628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, G.; Sun, H.; An, L.; Zhao, R.; Liu, M.; Tang, W.; Li, M.; Yan, X.; Ma, Y.; et al. Exploring Multi-Features in UAV Based Optical and Thermal Infrared Images to Estimate Disease Severity of Wheat Powdery Mildew. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 225, 109285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Qi, Y.; Yang, F.; Yi, X.; Guo, S.; Wu, P.; Yuan, Q.; Xu, T. Early Detection of Rice Blast Using UAV Hyperspectral Imagery and Multi-Scale Integrator Selection Attention Transformer Network (MS-STNet). Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 231, 110007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Khan, H.A.; Kootstra, G. Improving Radiometric Block Adjustment for UAV Multispectral Imagery under Variable Illumination Conditions. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhou, J.; Ma, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Ding, L.; Tang, W.; Pakezhamu, N.; Meng, L. Removing Temperature Drift and Temporal Variation in Thermal Infrared Images of a UAV Uncooled Thermal Infrared Imager. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2023, 203, 392–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messina, G.; Modica, G. Applications of UAV Thermal Imagery in Precision Agriculture: State of the Art and Future Research Outlook. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, S.; Lu, H. Dataset Meta-Level and Statistical Features Affect Machine Learning Performance. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schott, J.R.; Salvaggio, C.; Volchok, W.J. Radiometric Scene Normalization Using Pseudoinvariant Features. Remote Sens. Environ. 1988, 26, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Lin, C.; Liu, G.; Wang, D.; Qin, S.; Li, A.; Xu, J.-L.; He, Y. Intelligent Agriculture: Deep Learning in UAV-Based Remote Sensing Imagery for Crop Diseases and Pests Detection. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1435016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochiai, S.; Kamada, E.; Sugiura, R. Comparative Analysis of RGB and Multispectral UAV Image Data for Leaf Area Index Estimation of Sweet Potato. Smart Agric. Technol. 2024, 9, 100579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yan, S.; Wang, W.; Yin, L.; Li, M.; Yu, Z.; Chang, S.; Hou, F. Monitoring Leaf Area Index of the Sown Mixture Pasture through UAV Multispectral Image and Texture Characteristics. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 214, 108333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Song, X.; Guo, W.; Guo, M.; Mao, Y.; Yang, G.; Feng, H.; Zhang, J.; Feng, Z.; Wang, J.; et al. Potato Late Blight Severity Monitoring Based on the Relief-mRmR Algorithm with Dual-Drone Cooperation. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 215, 108438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, S.; Rischbeck, P.; Schmidhalter, U. Comparing the Performance of Active and Passive Reflectance Sensors to Assess the Normalized Relative Canopy Temperature and Grain Yield of Drought-Stressed Barley Cultivars. Field Crops Res. 2015, 177, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.A. Wide Dynamic Range Vegetation Index for Remote Quantification of Biophysical Characteristics of Vegetation. J. Plant Physiol. 2004, 161, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Kaufman, Y.J.; Stark, R.; Rundquist, D. Novel Algorithms for Remote Estimation of Vegetation Fraction. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 80, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, C.F. Derivation of Leaf-Area Index from Quality of Light on the Forest Floor. Ecology 1969, 50, 663–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huete, A.R. A Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Index (SAVI). Remote Sens. Environ. 1988, 25, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Huete, A.R.; Didan, K.; Miura, T. Development of a Two-Band Enhanced Vegetation Index without a Blue Band. Remote Sens. Environ. 2008, 112, 3833–3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouse, J.W., Jr.; Haas, R.H.; Schell, J.A.; Deering, D.W. Monitoring Vegetation Systems in the Great Plains with Erts. NASA Spec. Publ. 1974, 351, 309. [Google Scholar]

- Gitelson, A.; Merzlyak, M.N. Quantitative Estimation of Chlorophyll-a Using Reflectance Spectra: Experiments with Autumn Chestnut and Maple Leaves. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 1994, 22, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Viña, A.; Arkebauer, T.J.; Rundquist, D.C.; Keydan, G.; Leavitt, B. Remote Estimation of Leaf Area Index and Green Leaf Biomass in Maize Canopies. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2003, 30, 1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S.; Daughtry, C.S.T.; Chappelle, E.W.; Mcmurtrey, J.E.; Walthall, C.L. The Use of High Spectral Resolution Bands for Estimating Absorbed Photosynthetically Active Radiation (A Par). In Proceedings of the 6th International Symposium on Physical Measurements and Signatures in Remote Sensing, CNES, Val D’Isere, France, 17–21 January 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Merzlyak, M.N.; Chivkunova, O.B. Optical Properties and Nondestructive Estimation of Anthocyanin Content in Plant Leaves. Photochem. Photobiol. 2001, 74, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roujean, J.-L.; Breon, F.-M. Estimating PAR Absorbed by Vegetation from Bidirectional Reflectance Measurements. Remote Sens. Environ. 1995, 51, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Kaufman, Y.J.; Merzlyak, M.N. Use of a Green Channel in Remote Sensing of Global Vegetation from EOS-MODIS. Remote Sens. Environ. 1996, 58, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Chehbouni, A.; Huete, A.R.; Kerr, Y.H.; Sorooshian, S. A Modified Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index. Remote Sens. Environ. 1994, 48, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.M. Evaluation of Vegetation Indices and a Modified Simple Ratio for Boreal Applications. Can. J. Remote Sens. 1996, 22, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondeaux, G.; Steven, M.; Baret, F. Optimization of Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Indices. Remote Sens. Environ. 1996, 55, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, A.; Pelham, S.; Culbreath, A.; Holbrook, C.C.; De Godoy, I.J.; Li, C. High Throughput Phenotyping of Tomato Spot Wilt Disease in Peanuts Using Unmanned Aerial Systems and Multispectral Imaging. IEEE Instrum. Meas. Mag. 2017, 20, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataoka, T.; Kaneko, T.; Okamoto, H.; Hata, S. Crop Growth Estimation System Using Machine Vision. In Proceedings of the 2003 IEEE/ASME International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Mechatronics (AIM 2003), Online, 20–24 July 2003; Volume 2, pp. b1079–b1083. [Google Scholar]

- Woebbecke, D.M.; Meyer, G.E.; Von Bargen, K.; Mortensen, D.A. Color Indices for Weed Identification Under Various Soil, Residue, and Lighting Conditions. Trans. ASAE 1995, 38, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, G.E.; Neto, J.C. Verification of Color Vegetation Indices for Automated Crop Imaging Applications. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2008, 63, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louhaichi, M.; Borman, M.M.; Johnson, D.E. Spatially Located Platform and Aerial Photography for Documentation of Grazing Impacts on Wheat. Geocarto Int. 2001, 16, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendig, J.; Yu, K.; Aasen, H.; Bolten, A.; Bennertz, S.; Broscheit, J.; Gnyp, M.L.; Bareth, G. Combining UAV-Based Plant Height from Crop Surface Models, Visible, and near Infrared Vegetation Indices for Biomass Monitoring in Barley. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinform. 2015, 39, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, E.R.; Cavigelli, M.; Daughtry, C.S.T.; Mcmurtrey, J.E.; Walthall, C.L. Evaluation of Digital Photography from Model Aircraft for Remote Sensing of Crop Biomass and Nitrogen Status. Precis. Agric. 2005, 6, 359–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, D.; Zhao, J.; Lan, Y.; Yan, C.; Yang, D.; Wen, Y. SPAD Inversion Model of Corn Canopy Based on UAV Visible Light Image. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. 2020, 51, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Tang, L.; Hupy, J.P.; Wang, Y.; Shao, G. A Commentary Review on the Use of Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) in the Era of Popular Remote Sensing. J. For. Res. 2021, 32, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, T.; LeDrew, E. The Determination of Optimal Threshold Levels for Change Detection Using Various Accuracy Indices. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 1988, 54, 1449–1454. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, J.; Tian, Y.; Cao, Y.; Wan, W.; Liu, K. Research on Rice Fields Extraction by NDVI Difference Method Based on Sentinel Data. Sensors 2023, 23, 5876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, L.J.; Ferrando, C.A.; Biurrun, F.N. Remote Sensing of Spatial and Temporal Vegetation Patterns in Two Grazing Systems. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 2009, 62, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syriopoulos, P.K.; Kalampalikis, N.G.; Kotsiantis, S.B.; Vrahatis, M.N. kNN Classification: A Review. Ann. Math. Artif. Intell. 2023, 93, 43–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanzieri, E.; Melgani, F. Nearest Neighbor Classification of Remote Sensing Images with the Maximal Margin Principle. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2008, 46, 1804–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Choo, K.K.R.; Wang, L.; Huang, F. SVM or Deep Learning? A Comparative Study on Remote Sensing Image Classification. Soft Comput. 2017, 21, 7053–7065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas, J.F.; Flores, J.J. The Application of Artificial Neural Networks to the Analysis of Remotely Sensed Data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2008, 29, 617–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewan, S.Y.Y.; Pagay, V.; Billa, L.; Tyerman, S.D.; Gautam, D.; Sparkes, D.; Chai, H.H.; Singh, A. The Feasibility of Using a Low-Cost near-Infrared, Sensitive, Consumer-Grade Digital Camera Mounted on a Commercial UAV to Assess Bambara Groundnut Yield. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2022, 43, 393–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, E.R.; Daughtry, C.S.T.; Eitel, J.U.H.; Long, D.S. Remote Sensing Leaf Chlorophyll Content Using a Visible Band Index. Agron. J. 2011, 103, 1090–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahir, S.A.D.M.; Omar, A.F.; Jamlos, M.F.; Azmi, M.A.M.; Muncan, J. A Review of Visible and Near-Infrared (Vis-NIR) Spectroscopy Application in Plant Stress Detection. Sens. Actuators Phys. 2022, 338, 113468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, A.M.; Chapman, W.K.; Prescott, C.E.; Nijland, W. Using Excess Greenness and Green Chromatic Coordinate Colour Indices from Aerial Images to Assess Lodgepole Pine Vigour, Mortality and Disease Occurrence. For. Ecol. Manag. 2016, 374, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Tao, H.; Li, Z.; Yang, G.; Zhao, C. Comparison of UAV RGB Imagery and Hyperspectral Remote-Sensing Data for Monitoring Winter Wheat Growth. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolin, Y.; Popova, A.; Yudina, L.; Grebneva, K.; Abasheva, K.; Sukhov, V.; Sukhova, E. RGB Indices Can Be Used to Estimate NDVI, PRI, and Fv/Fm in Wheat and Pea Plants Under Soil Drought and Salinization. Plants 2025, 14, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hlatshwayo, S.T.; Mutanga, O.; Lottering, R.T.; Kiala, Z.; Ismail, R. Mapping Forest Aboveground Biomass in the Reforested Buffelsdraai Landfill Site Using Texture Combinations Computed from SPOT-6 Pan-Sharpened Imagery. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinform. 2019, 74, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, N.; Coops, N.C.; Obrknezev, N. Normalization Method for Multi-Sensor High Spatial and Temporal Resolution Satellite Imagery with Radiometric Inconsistencies. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 164, 104893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghimi, A.; Sadeghi, V.; Mohsenifar, A.; Celik, T.; Mohammadzadeh, A. LIRRN: Location-Independent Relative Radiometric Normalization of Bitemporal Remote-Sensing Images. Sensors 2024, 24, 2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, J.; Li, S.; Bai, X.; Gan, W.; Wu, J.; Li, X. RS-NormGAN: Enhancing Change Detection of Multi-Temporal Optical Remote Sensing Images through Effective Radiometric Normalization. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2025, 221, 324–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourazar, H.; Samadzadegan, F.; Javan, F.D. Aerial Multispectral Imagery for Plant Disease Detection: Radiometric Calibration Necessity Assessment. Eur. J. Remote Sens. 2019, 52, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.R.; Parida, B.R.; Venus, V.; Saha, S.K.; Dadhwal, V.K. Analysis of Agricultural Drought Using Vegetation Temperature Condition Index (VTCI) from Terra/MODIS Satellite Data. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2012, 184, 7153–7163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, N.; Sousa, J.J.; Couto, P.; Bento, A.; Pádua, L. Combining UAV-Based Multispectral and Thermal Infrared Data with Regression Modeling and SHAP Analysis for Predicting Stomatal Conductance in Almond Orchards. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheruy, F.; Dufresne, J.L.; Aït Mesbah, S.; Grandpeix, J.Y.; Wang, F. Role of Soil Thermal Inertia in Surface Temperature and Soil Moisture-Temperature Feedback. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 2017, 9, 2906–2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zhang, D.; Li, L.; Zhang, Z.; Liang, X.; Wen, Q.; Chen, G.; Wu, Q.; Zhai, Y. Effect of Planting Density on Canopy Structure, Microenvironment, and Yields of Uniformly Sown Winter Wheat. Agronomy 2023, 13, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, R.K.; Uddin, M.N.; Uddin, M.A.; Aryal, S.; Khraisat, A. Enhancing K-Nearest Neighbor Algorithm: A Comprehensive Review and Performance Analysis of Modifications. J. Big Data 2024, 11, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shdefat, A.Y.; Mostafa, N.; Al-Arnaout, Z.; Kotb, Y.; Alabed, S. Optimizing HAR Systems: Comparative Analysis of Enhanced SVM and k-NN Classifiers. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2024, 17, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Qu, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, X.; Hu, B. Feature-Level Fusion Approaches Based on Multimodal EEG Data for Depression Recognition. Inf. Fusion 2020, 59, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujatha, R.; Krishnan, S.; Chatterjee, J.M.; Gandomi, A.H. Advancing Plant Leaf Disease Detection Integrating Machine Learning and Deep Learning. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, C.A.; Crawford, M.M.; Tuinstra, M.R. Integrating Multi-Modal Remote Sensing, Deep Learning, and Attention Mechanisms for Yield Prediction in Plant Breeding Experiments. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1408047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pande, S.; Banerjee, B. Self-Supervision Assisted Multimodal Remote Sensing Image Classification with Coupled Self-Looping Convolution Networks. Neural Netw. 2023, 164, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carisse, O.; Levasseur, A.; Provost, C. Influence of Leaf Wetness Duration and Temperature on Infection of Grape Leaves by Elsinoë Ampelina under Controlled and Vineyard Conditions. Plant Dis. 2020, 104, 2817–2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morkeliūnė, A.; Rasiukevičiūtė, N.; Valiuškaitė, A. Meteorological Conditions in a Temperate Climate for Colletotrichum Acutatum, Strawberry Pathogen Distribution and Susceptibility of Different Cultivars to Anthracnose. Agriculture 2021, 11, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, D. Intelligent Pest Forecasting with Meteorological Data: An Explainable Deep Learning Approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 252, 124137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data | Healthy | Disease | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temporal Phase 1 (T1) | 12 October 2024 | 104 | 80 | 184 |

| Temporal Phase 2 (T2) | 23 October 2024 | 84 | 120 | 204 |

| Temporal Phase 3 (T3) | 10 October 2025 | 96 | 88 | 184 |

| 284 | 288 | 572 |

| Sensors | Spectral Region (μm) | Image Resolution (Pixels) | Equivalent Focal Length (mm) | Diagonal Field of View (D°) | RTK Accuracy | Weight (g) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M3M | RGB | / | 5280 × 3956 | 24 | 84° | Horizontal: 1 cm + 1 ppm; Vertical: 1.5 cm + 1 ppm | 951 (Propeller + RTK module) |

| MS | Green: 0.560 ± 0.016 | 2592 × 1944 | 25 | 73.91° | |||

| Red: 0.650 ± 0.016 | |||||||

| RedEdge: 0.730 ± 0.016 | |||||||

| NIR: 0.860 ± 0.026 | |||||||

| M3T | RGB-Tele | / | 4000 × 3000 | 162 | 15° | ||

| TIR | 8.0–14.0 | 640 × 512 | 40 | 61° | 920 (Propeller) |

| Feature Type | Feature Name |

|---|---|

| Sp | SR, NIR, NormRRE, VARIG, Red, RedEdge, ARI |

| Te | NIR_D[MEA,HOM], NIR_R[SEC,MEA], RedEdge_N[MEA,SEC], Gray_R[MEA,DIS], Gray_D[MEA,DIS], Gray_N[VAR,DIS] |

| Co | ExR, R, ExG, B |

| Th | VSRT |

| Feature Type | Metrics | KNN | SVM | MLP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sp | Accuracy | 89.10% | 93.59% | 90.38% |

| Precision | 89.30% | 93.64% | 90.40% | |

| Recall | 89.01% | 93.55% | 90.36% | |

| F1-Score | 89.07% | 93.58% | 90.37% | |

| Te | Accuracy | 89.74% | 90.38% | 93.59% |

| Precision | 89.74% | 90.41% | 93.59% | |

| Recall | 89.77% | 90.43% | 93.59% | |

| F1-Score | 89.74% | 90.38% | 93.59% | |

| Co | Accuracy | 85.90% | 85.90% | 85.26% |

| Precision | 85.90% | 85.90% | 85.32% | |

| Recall | 85.92% | 85.92% | 85.20% | |

| F1-Score | 85.90% | 85.90% | 85.23% | |

| Th | Accuracy | 64.10% | 67.95% | 68.59% |

| Precision | 64.21% | 71.64% | 69.56% | |

| Recall | 64.18% | 68.45% | 68.85% | |

| F1-Score | 64.10% | 66.88% | 68.37% | |

| Sp + Te | Accuracy | 93.59% | 91.67% | 85.90% |

| Precision | 93.59% | 91.68% | 85.95% | |

| Recall | 93.59% | 91.64% | 85.95% | |

| F1-Score | 93.59% | 91.66% | 85.90% | |

| Sp + Co | Accuracy | 94.23% | 92.95% | 89.74% |

| Precision | 94.33% | 92.96% | 89.80% | |

| Recall | 94.18% | 92.93% | 89.80% | |

| F1-Score | 94.22% | 92.94% | 89.74% | |

| Sp + Th | Accuracy | 95.51% | 94.23% | 92.95% |

| Precision | 95.53% | 94.33% | 92.97% | |

| Recall | 95.49% | 94.18% | 92.99% | |

| F1-Score | 95.51% | 94.22% | 92.95% | |

| Sp + Te + Co + Th | Accuracy | 92.95% | 90.38% | 92.95% |

| Precision | 93.04% | 90.41% | 92.96% | |

| Recall | 92.89% | 90.43% | 92.93% | |

| F1-Score | 92.93% | 90.38% | 92.94% |

| Model | TN | FP | FN | TP | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KNN | 72 | 4 | 3 | 77 | 95.51% | 95.53% | 95.49% | 95.51% |

| SVM | 70 | 6 | 3 | 77 | 94.23% | 94.33% | 94.18% | 94.22% |

| MLP | 72 | 4 | 7 | 73 | 92.95% | 92.97% | 92.99% | 92.95% |

| Feature Type | T1 Val. Acc. | T2 Val. Acc. | Mean Val. Acc. (T1, T2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sp | 100.00% | 98.04% | 99.02% |

| Te | 100.00% | 96.08% | 98.04% |

| Co | 89.13% | 86.27% | 87.70% |

| Th | 89.13% | 58.82% | 73.98% |

| Sp + Te | 97.83% | 96.08% | 96.96% |

| Sp + Co | 97.83% | 100.00% | 98.92% |

| Sp + Th | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

| Sp + Te + Co + Th | 97.83% | 100.00% | 98.92% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Yuan, L.; Li, X.; Zeng, F.; Xu, K.; Huang, W.; Shen, Z. UAV-Based Multimodal Monitoring of Tea Anthracnose with Temporal Standardization. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2270. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15212270

Yu Q, Zhang J, Yuan L, Li X, Zeng F, Xu K, Huang W, Shen Z. UAV-Based Multimodal Monitoring of Tea Anthracnose with Temporal Standardization. Agriculture. 2025; 15(21):2270. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15212270

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Qimeng, Jingcheng Zhang, Lin Yuan, Xin Li, Fanguo Zeng, Ke Xu, Wenjiang Huang, and Zhongting Shen. 2025. "UAV-Based Multimodal Monitoring of Tea Anthracnose with Temporal Standardization" Agriculture 15, no. 21: 2270. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15212270

APA StyleYu, Q., Zhang, J., Yuan, L., Li, X., Zeng, F., Xu, K., Huang, W., & Shen, Z. (2025). UAV-Based Multimodal Monitoring of Tea Anthracnose with Temporal Standardization. Agriculture, 15(21), 2270. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15212270