Abstract

To clarify the optimal water regulation strategy for spring wheat in arid areas, this study set up three irrigation methods [film-mulched drip irrigation (FD), non-mulched drip irrigation (ND), non-mulched subsurface drip irrigation (MD)] and five water treatments [CK: 80% field capacity; W1–W4: irrigation amounts were 90%, 80%, 70%, and 60% of CK, respectively] in the Shiyang River Basin during 2023–2024. The effects of these treatments on the phenotype, yield, and water use efficiency (WUE) of spring wheat were investigated. The results showed that under the same water treatment, the leaf area index (LAI), SPAD value, and stem diameter (SD) significantly decreased with the reduction in irrigation amount (p < 0.05), while plant height (HC) was less affected. FD performed optimally under the W1 treatment: its yield reached 11,868.93 kg·ha−1, which was 54.88% and 38.72% higher than that of ND and MD, respectively; and its WUE reached 4.36 kg/m3, which was 123.19% and 100.83% higher than that of ND and MD, respectively. ND performed better under the CK treatment: its yield was 10,044.33 kg·ha−1, which was 27.07% and 12.25% higher than that of FD and MD, respectively. Annual precipitation had a significant impact: when precipitation was 175 mm in 2023, ND showed an obvious advantage; when precipitation decreased to 110 mm in 2024, FD exhibited stronger stress resistance. The study concludes that FD is suitable for moderate to severe water stress, while ND is suitable for sufficient water conditions or mild stress. This can provide a basis for water-saving and the high-yield production of spring wheat in arid areas.

1. Introduction

Spring wheat is one of the core food crops in temperate arid and semi-arid regions worldwide, and it serves as a pillar crop for ensuring regional food security and the stability of the agricultural economy in the arid inland regions of northwestern China [1,2]. From an economic perspective, spring wheat has a short growth period (100–120 days), which is compatible with the limited irrigation season in arid regions. Its grains not only serve as a staple food source for local residents, but are also processed into derived products such as flour and germ oil, driving the development of the regional agricultural product processing industry [2,3,4]. In terms of nutritional value, spring wheat grains contain 12–15% high-quality protein, abundant B vitamins, and dietary fiber, which can effectively make up for the nutritional gap caused by an insufficient supply of vegetables and fruits in arid regions [5,6,7,8]. Especially in the arid and semi-arid regions of northwestern China, where cultivated land resources are limited and precipitation is scarce, the drought-tolerant characteristics of spring wheat make it easier to achieve stable cultivation compared with maize and cotton [9]. Its yield fluctuation directly affects the local grain self-sufficiency rate and farmers’ income; therefore, optimizing the water management of spring wheat holds irreplaceable significance for regional livelihoods and the sustainable development of agriculture [10].

The arid inland regions of northwestern China are among the areas with the most prominent contradiction between water supply and demand in China. Taking the Shiyang River Basin (the study area of this research) as an example, the basin covers an area of 41,600 km2, with a total water resource of only about 1.7 billion m3, an average annual precipitation of less than 200 mm (only 164 mm in some areas), and a surface evaporation as high as 2000 mm, making it a typical “water-deficient” agricultural ecosystem [11]. Agricultural water use in this region accounts for more than 70% of total water consumption [11], among which irrigation water for spring wheat accounts for 35–40% of the total irrigation water for crops [12]. However, traditional irrigation methods suffer from severe water waste: conventional flood irrigation wets the soil by flooding the field with large amounts of water, leading to more than 30% of water loss through deep percolation and surface evaporation, with a water use efficiency (WUE) of only 1.2–1.8 kg/m3 [13]. Even after the promotion of drip irrigation technology, the differences in the effects of different water regulation modes remain unclear, resulting in irrigation management mostly relying on experience, and making it difficult to balance the dual needs of “water conservation” and “high yield”. This practical contradiction makes optimizing the water regulation technology for spring wheat a key breakthrough to alleviate water scarcity and ensure food security in the Shiyang River Basin.

Currently, the mainstream water regulation methods for spring wheat can be divided into three categories, each with its own advantages and disadvantages and different applicable scenarios. The first category is conventional flood irrigation, which introduces water into the field through channels to infiltrate the soil via surface runoff. It features simple operation and low equipment cost but extremely low water use efficiency, and is only suitable for irrigation areas with relatively sufficient water resources. This has been gradually phased out in arid regions such as the Shiyang River Basin [14]. The second category is drip irrigation technology including film-mulched drip irrigation (FD) and non-mulched drip irrigation (ND). FD reduces soil evaporation by covering the soil surface with plastic film (which can decrease evaporative loss by 20–30%) while maintaining stable moisture in the root zone. It has been proven to improve WUE in crops such as cotton and maize, but its phenotypic response and yield adaptability in the late filling stage of spring wheat still need to be verified [10]. ND does not require film mulching, saving the cost of plastic film and the film recycling process; however, surface soil moisture is easily affected by evaporation, which may exacerbate crop water stress in dry years [15]. The third category is non-mulched shallow-buried drip irrigation (MD), an emerging water-saving technology that buries drip tapes at a depth of 10–15 cm to reduce surface evaporation while avoiding plastic film residue pollution. However, there are very few studies on MD for spring wheat at present, and systematic conclusions on the dynamic changes of its phenotypic indicators and the response patterns of yield and WUE to water have not yet been formed [16]. Existing studies have mostly focused on the comparison of water gradients under a single irrigation method, lacking direct comparisons of FD, ND, and MD under the same water conditions. This makes it impossible to clarify the optimal regulation mode under different degrees of water stress, and this research gap restricts the precise upgrading of spring wheat water management in arid regions [17].

Growth phenotypic indicators, such as leaf area index (LAI), chlorophyll content (SPAD), stem diameter (SD), and plant height (HC), are core tools for diagnosing the water response of spring wheat, and their dynamic changes are directly related to the yield formation process [18]. Specifically, LAI reflects the size of the crop’s photosynthetic area: when water is sufficient, LAI maintains a high level, capturing more light energy for dry matter accumulation; whereas water stress causes leaf curling and premature senescence, leading to a decrease in LAI and thus a reduction in photosynthates [19]. SPAD values represent the leaf chlorophyll content, directly determining photosynthetic efficiency; water deficit inhibits chlorophyll synthesis and accelerates its degradation, resulting in a decrease in SPAD and ultimately affecting grain filling. SD reflects the development status of stems: sufficient water promotes stem thickening, enhancing lodging resistance and nutrient transport efficiency, while water stress leads to thin and weak stems, increasing the risk of lodging. Although HC is less affected by water, it can serve as an auxiliary indicator for judging the overall growth status of crops. By monitoring the response of these phenotypic indicators to water regulation, the critical period of spring wheat water stress (e.g., the filling stage) can be accurately identified, providing a basis for formulating “on-demand irrigation” plans. Therefore, clarifying the dynamic patterns of phenotypic indicators under different water regulation methods is a prerequisite for achieving the coordination of “water conservation and high yield” for spring wheat.

Based on the above background and research gaps, this study took spring wheat in the Shiyang River Basin as the research object, and through a 2023–2024 field experiment, explored the effects of three irrigation methods (film-mulched drip irrigation (FD), non-mulched drip irrigation (ND), non-mulched shallow-buried drip irrigation (MD)) and five water treatments (CK: 80% field capacity; W1–W4: irrigation amounts were 90%, 80%, 70%, and 60% of CK in sequence) on the growth phenotypic indicators, yield, and WUE of spring wheat. The aim was to screen the optimal water regulation mode suitable for the arid regions of northwestern China [20]. This study puts forward the following hypotheses:

- Under the same water treatment, the phenotypic indicators (LAI, SPAD, SD) of FD are significantly better than those of ND and MD, especially in the late filling stage—film mulching can reduce soil evaporation, maintain stable root water supply, and delay leaf senescence and stem degradation;

- FD is more likely to balance high yield and high WUE under moderate to severe water stress (W1: 90% CK, W4: 60% CK), while ND performs better under full water supply or mild stress (CK, W2: 80% CK, W3: 70% CK)—ND has no film mulching barrier, so it can avoid root waterlogging when water is sufficient, while the water retention advantage of FD is more prominent under stress conditions;

- MD is sensitive to water, with the highest yield under full water supply (CK); however, due to the absence of film mulching and the shallow burial of drip tapes, its WUE is lower than that of FD, and the yield reduction under water stress is greater than that of FD and ND.

The results of this study can provide a theoretical basis and technical reference for the water-saving and high-yield irrigation management of spring wheat in the arid regions of northwestern China.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Study Area

2.1.1. Geographical and Climatic Characteristics

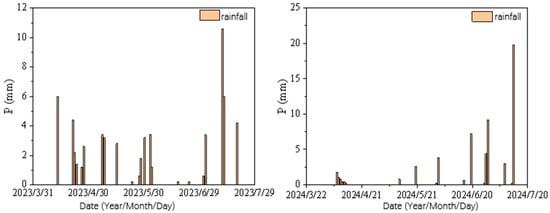

This study was conducted at the Shiyang River Experimental Station of China Agricultural University (geographic coordinates: 37°52′ N, 102°50′ E, altitude 1581 m) from 2023 to 2024. This region has a temperate arid continental climate with abundant light and heat resources, with the annual average sunshine hours exceeding 3000 h, multi-year average temperature of about 8 °C, frost-free period of 150 days, and large day–night temperature difference, all in favor of agricultural production [21]. However, this region is arid with scarce annual rainfall, with an annual average rainfall of 164 mm, a water surface evaporation of up to 2000 mm, scarce water resources, and a groundwater depth of 40–50 m. During the experimental period (spring wheat growth stage: 30 March–26 July 2023; 30 March–14 July 2024), the routine meteorological data of the experimental station were obtained through continuous monitoring by the station’s automatic weather station (Weather Hawk USA) including wind speed, rainfall, solar radiation, and other parameters. The instrument automatically recorded one set of data every 15 min. The average precipitation during the entire growth stage of spring wheat from 2023 to 2024 is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The average precipitation during the entire growth period of spring wheat from 2023 to 2024.

2.1.2. Soil Characteristics

The soil type of the experimental field was sandy loam (with the dominant texture in the 0–40 cm soil layer). The basic physical and chemical properties were determined via soil sampling, and the specific parameters were as follows: the average dry bulk density of the 1 m soil layer was 1.56 g/cm3, the field capacity (FC) was 0.09 g/g, the permanent wilting point was 0.03 g/g, the total porosity was 40%, and the saturated hydraulic conductivity was 1.5 × 10−4 m/s; the effective root depth was 40 cm. The basic soil fertility of the 0–40 cm soil layer is shown in Table 1, where the organic matter content was 8.96 g/kg in the 0–20 cm layer and 7.71 g/kg in the 20–40 cm layer. Therefore, the contents of nutrients such as total nitrogen, total phosphorus, and available potassium meet the basic fertility requirements for spring wheat cultivation in arid regions, with no nutrient stress risk.

Table 1.

Basic soil fertility of the 0–40 cm soil layer.

2.1.3. Irrigation Water Source Characteristics

The irrigation water source used in this experiment was groundwater from the experimental station (at a depth of 40–50 m), which was directly pumped through drilling wells and applied to the drip irrigation system. The physical and chemical properties of the water source were determined with reference to the Standards for Irrigation Water Quality (GB 5084-2021), and the results are as follows:

pH value: 7.5–8.0 (neutral to slightly alkaline, meeting the irrigation requirements);

Electrical conductivity (EC): 0.35–0.45 dS/m (low salinity);

Sodium adsorption ratio (SAR): 2.1–2.8 (<3, no alkalization risk);

Total hardness (calculated as CaCO3): 120–150 mg/L (medium hardness);

Contents of potentially toxic ions: Na+ 25–30 mg/L, Cl− 18–22 mg/L, and B (boron) 0.2–0.3 mg/L. All of these values were lower than the limits specified in the national standard (Na+ < 200 mg/L, Cl− < 300 mg/L, B < 1.0 mg/L).

The water source is free from heavy metal or toxic ion pollution and is suitable for spring wheat irrigation.

2.2. Experimental Design

2.2.1. Setting of Irrigation Methods and Water Treatments

The experiment set three irrigation methods, namely FD, ND, and MD. Under each irrigation method, five water treatments were assigned (i.e., the full irrigation treatment CK (80% FC, FC represents “field capacity”) as the control, and W1 (90% CK), W2 (80% CK), W3 (70% CK), and W4 (60% CK)). Each treatment was replicated three times, and the area of each plot was 5 m × 5.4 m = 27 m2.

A randomized complete block design (RCBD) was adopted in this experiment to eliminate systematic biases caused by soil heterogeneity and microclimate differences. The specific implementation steps are as follows:

Based on soil fertility indices (organic matter, total nitrogen, etc.) in the 0–40 cm layer, the experimental field was divided into three uniform blocks. Statistical tests showed that there was no significant difference in soil fertility among the blocks (p > 0.05), ensuring the homogeneity of soil and microenvironment within each block. Within each block, first, the three irrigation methods (FD, ND, MD) were randomly assigned as the main treatments. Then, under each irrigation method, the five water treatments (CK, W1–W4) were randomly assigned as sub-treatments. The aforementioned random assignment process was independently conducted in the three blocks. Finally, each combination of “irrigation method + water treatment” obtained three replications in different blocks (meeting the replication requirement for statistical tests). The field layout of spring wheat (as shown in Figure 2) is the actual presentation of the randomized design: each column corresponds to the main treatment (irrigation method) within the same block. Due to the control of pipeline costs, the water treatments under the same column (i.e., the same irrigation method) were arranged in the sequence of CK, W1, W2, W3, and W4. However, the core logic—“first randomly assign main and sub-treatments within blocks, then ensure the randomness and balance of treatment combinations through multi-block replication”—remained unchanged, which effectively eliminated systematic biases.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of spring wheat field layout.

2.2.2. Planting and Management Measures

The “Yongliang 4” spring wheat was planted. The FD treatment applied a hole seeder for sowing, and the ND and MD treatments used a drill seeder, with a row spacing of 15 cm. One drip tape was laid for every two rows, with a spacing of 30 cm, a dripper flow rate of 3 L·h−1, and a spacing of 150 mm. The growth period in 2023 was 119 days, from 30 March to 26 July, and in 2024, it was 107 days, from 30 March to 14 July. The sowing density was about 6 million grains·ha−2.

With reference to the FAO 56 Standard on Crop Water Requirements and by integrating meteorological data (including solar radiation, air temperature, etc.) from the experimental station, the Penman–Monteith equation was adopted to calculate the reference evapotranspiration (ET0) of spring wheat. Meanwhile, the crop coefficients (Kc) for each growth stage were determined as follows:

Seedling stage (30 March–20 April): Kc = 0.35;

Jointing stage (21 April–10 May): Kc = 0.75;

Heading stage (11 May–30 May): Kc = 0.95;

Grain filling stage (1 June–30 June): Kc = 0.85;

Maturity stage (1 July–harvest date): Kc = 0.45.

Based on the above parameters, the total crop water requirement of spring wheat was calculated: it reached 452 mm in 2023 and 418 mm in 2024. The irrigation amount was designed following the principle of meeting the water requirement deficit in each growth stage.

During the experiment, the fertilizer dosage was the same for each treatment. In 2023, 900 kg·hm−2 of urea was applied with the first irrigation on 8 May, and 600 kg·hm−2 of urea was applied with the first water treatment on 24 May. Field management measures such as weeding and pesticide application were carried out. Irrigation started from the jointing stage, and water regulation was carried out according to the lower limit of soil moisture content (75% FC at the jointing stage, 80% FC at the heading stage, 80% FC at the filling stage, and 65% FC at the maturity stage). When the average soil moisture content at 0–40 cm depth in the CK area was below the lower limit set for the corresponding growth stage, irrigation was carried out according to the designed irrigation amount for each treatment.

2.3. Determination Indicators and Methods

2.3.1. Determination of Spring Wheat Growth Phenotypic Indicators

Measurement was conducted at four key growth stages of spring wheat, namely the jointing stage, heading stage, grain filling stage, and maturity stage. For each plot, 10 plants with uniform growth were randomly selected, and the specific methods are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Determination methods for growth phenotypic indicators of spring wheat.

2.3.2. Determination of Yield and Water Use Efficiency

Yield: In the maturity stage, the “diagonal three-point sampling method” was used. Three 1 m × 1 m quadrats were selected in each plot, the number of spikes per unit area was counted, the 1000-grain weight and the number of grains per spike were measured, and the yield was calculated using the formula: Yield (kg·ha−1) = Number of spikes per unit area × Number of grains per spike × 1000-grain weight (g) × 10−6 × 10,000.

Actual water consumption (ET, mm): This was determined using the water balance method, with the formula: ET = I + P − R − D; where I is the irrigation amount (recorded by a flow meter), P is the rainfall (recorded by an automatic weather station), R is the surface runoff (there is no runoff under drip irrigation, so R = 0), and D is the deep percolation (no obvious percolation was monitored in the 0–100 cm soil layer, so D ≈ 0). The monitoring method for the deep percolation amount (D) is as follows: in each plot, three sets of TDR soil moisture sensors (model: TDR-300, measurement accuracy: ±0.01 g/g) were vertically installed in the 0–100 cm soil layer, with the sensors placed 15 cm on either side of the drip tape. The volumetric soil water content (θv) was measured once at 10:00 a.m. every 3 days. The calculation logic for deep percolation amount is as follows: when θv exceeds the volumetric water content corresponding to field capacity (θFC = 0.09 g/g ÷ 1.56 g/cm3 × 100% = 5.77%), the excess water percolates downward. The calculation formula is: D = (Measured θv − θFC) × Soil layer thickness (100 cm) × Bulk density (1.56 g/cm3) × Plot area (27 m2). Monitoring results during the experiment showed that the maximum θv in the 0–100 cm soil layer across all treatments from 2023 to 2024 was 5.52% (lower than θFC), and no deep percolation occurred; thus, D ≈ 0. Meanwhile, there was no surface runoff (R = 0) in the drip irrigation system. Therefore, the water balance equation was simplified to ET ≈ I + P.

Water use efficiency (WUE): This was calculated according to the formula WUE = Y/ET, where Y is the grain yield (kg·ha−1) and ET is the total water consumption during the whole growth period (mm). The unit conversion is as follows: 1 ha·mm = 10 m3.

2.4. Data Analysis Methods

Excel 2021 was used for data collation, and SPSS 26.0 for the analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Pearson correlation analysis. The significance level was set at p < 0.05. Origin 2021 was employed to draw charts to compare the differences in the spring wheat growth phenotypic indicators and water use efficiency under different irrigation methods and water treatments.

3. Results

3.1. Responses of Spring Wheat Growth Phenotypic Indicators to Water Regulation

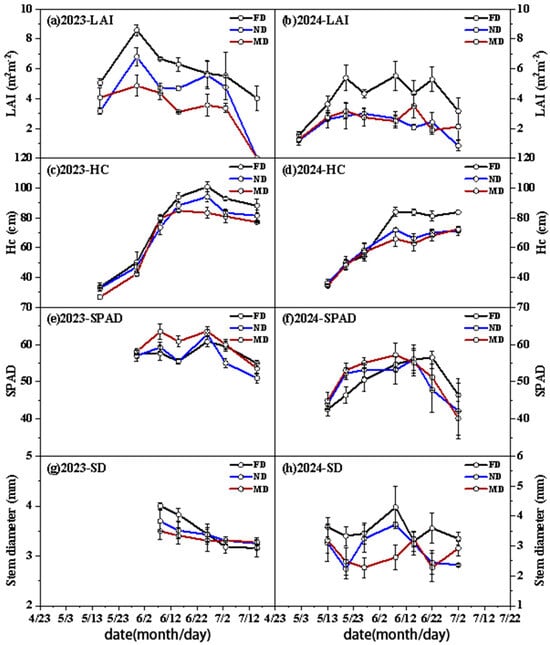

Under the same water treatment, the leaf area index (LAI), chlorophyll content (SPAD), and stem diameter (SD) of spring wheat all significantly decreased with the reduction in irrigation amount (p < 0.05), while plant height (HC) was not significantly affected by the irrigation amount (p > 0.05). Under the same irrigation method, the growth phenotypic indicators of film-mulched drip irrigation (FD) were significantly better than those of non-mulched drip irrigation (ND) and non-mulched shallow-buried drip irrigation (MD) in the late filling stage (p < 0.05).

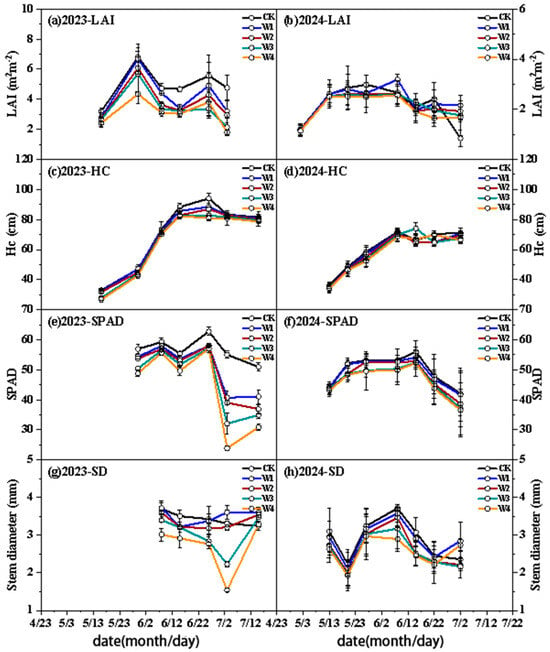

Under the full irrigation treatment (CK, 80% field capacity (FC)), the effects of the three irrigation methods on LAI, HC, SPAD, and SD of spring wheat are shown in Figure 3. The LAI under FD was consistently significantly higher than that under ND and MD (p < 0.05); specifically, the LAI under FD was 16.15–259.70% higher than that under ND and 64.65–274.52% higher than that under MD. HC reached the maximum value in the maturity stage, and the HC under FD was significantly better than that under ND and MD (p < 0.05), being 1.54–18.87% higher than that under ND and 8.87–24.41% higher than that under MD. SPAD first increased and then decreased during the whole growth period; in the late filling stage, the SPAD under FD surpassed that under the other two methods and became the highest. Before the filling stage, the SD under the three irrigation methods ranked as FD > ND > MD (p < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Changes in the physiological and growth indicators of spring wheat under three irrigation methods with CK water treatment.

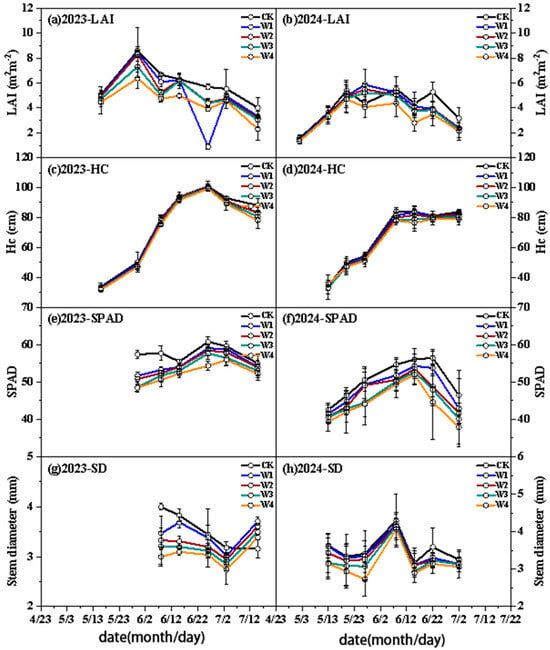

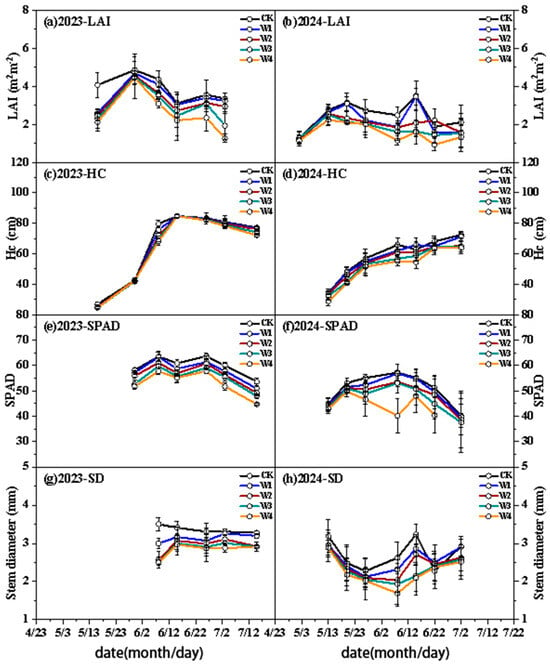

Under the FD treatment, the growth indicators of the five water treatments are shown in Figure 4. LAI first increased and then decreased during the whole growth period. The LAI under the CK treatment reached the peak in the heading stage, while the LAI under the W1 to W4 treatments peaked earlier in the jointing stage, and significantly decreased with the reduction in irrigation amount. HC began to increase rapidly from the jointing stage and reached the maximum in the maturity stage, with no significant differences among different water treatments (p > 0.05). SPAD showed a single-peak curve change, reaching the peak in the filling stage and significantly decreased with the reduction in irrigation amount (p < 0.05). SD reached the maximum in the middle and late heading stage and significantly decreased with the reduction in irrigation amount (p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Comparison of various indicators of spring wheat during the whole growth period under five water treatments with FD.

Under ND, the growth indicators of the five water treatments are shown in Figure 5. LAI dynamics showed a trend of “first increasing and then decreasing”, and was positively correlated with irrigation amount (p < 0.05). The LAI under the CK treatment reached the peak in the jointing stage, while the peak of LAI under the W1 to W4 treatments was delayed to the heading stage. The growth pattern of HC was consistent among all treatments, with no significant differences between treatments (p > 0.05). SPAD significantly decreased with the increase in water stress degree (p < 0.05) and reached the peak in the filling stage. The change in SD was positively correlated with the irrigation amount. In 2023, the SD under the CK and W1 treatments was significantly higher than that under W2–W4 (p < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Comparison of various indicators of spring wheat during the whole growth period under five water treatments with ND.

Under MD, the growth indicators of the five water treatments are shown in Figure 6. LAI dynamics showed a trend of “first increasing and then decreasing”, and the timing of its peak varied with water treatments. HC continued to grow until maturity, with no significant difference among different water treatments (p > 0.05). SPAD showed an overall single-peak curve and significantly decreased with the reduction in irrigation amount (p < 0.05). SD reached the maximum in the middle and late filling stage, and also significantly decreased with the reduction in irrigation amount (p < 0.05).

Figure 6.

Comparison of various indicators of spring wheat during the whole growth period under five water treatments with MD.

3.2. Responses of Spring Wheat Yield and Water Use Efficiency to Water Regulation

Interannual differences were found in the yield and water use efficiency (WUE), which were affected by precipitation (175 mm in 2023 and 110 mm in 2024).

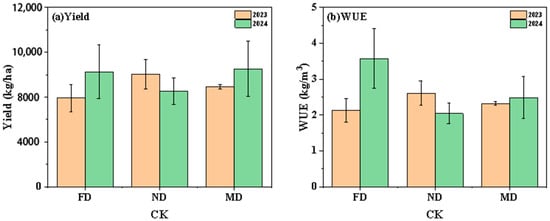

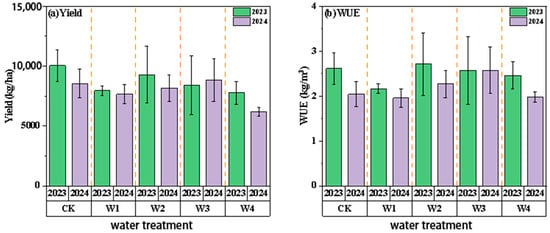

Under the full irrigation treatment (CK), the yield and WUE of the three irrigation methods are shown in Figure 7. In 2023, the yield under the ND treatment was the highest, 27.07% and 12.25% higher than that under FD and MD, respectively (p < 0.05); in 2024, the MD treatment produced the best yield, 2.58% and 23.22% higher than that under FD and ND, respectively. In terms of WUE, in 2023, the WUE under the ND treatment was the highest, 22.62% and 12.32% higher than that under FD and MD, respectively; in 2024, the WUE under the FD treatment was significantly the best, 74.78% and 43.42% higher than that under ND and MD, respectively (p < 0.05).

Figure 7.

Yield and WUE of spring wheat under three irrigation methods with CK treatment.

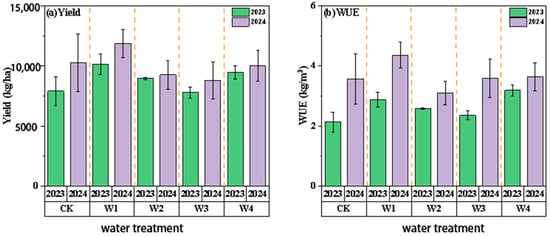

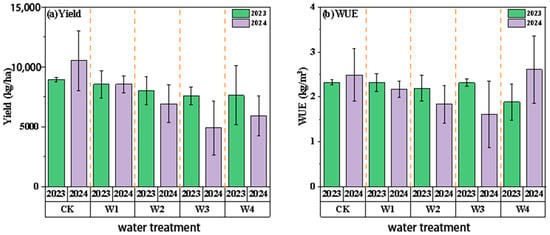

Under FD, the yield and WUE of the five water treatments are shown in Figure 8. The two-year data showed that the yield first increased and then decreased with the reduction in the irrigation amount. In 2023, the W1 treatment generated the highest yield, 22.03%, 11.71%, 23.26%, and 6.44% higher than CK, W2, W3, and W4, respectively (p < 0.05); in 2024, the W1 treatment still produced the highest yield. In terms of WUE, the WUE under water stress treatments was significantly higher than that under full irrigation (CK) in both years. In 2023, the W4 treatment had the highest WUE, 49.60% higher than CK, while in 2024, the W1 treatment had the highest WUE, 22.18% higher than CK.

Figure 8.

Comparison of yield and WUE of spring wheat under five water treatments with FD.

Under ND conditions, the yield and WUE of the five water treatments are shown in Figure 9. In 2023, the CK treatment (full irrigation) had the highest yield, 20.89%, 7.56%, 16.49%, and 22.58% lower than the W1, W2, W3, and W4 treatments, respectively (p < 0.05); in 2024, the W3 treatment had the highest yield. In terms of WUE, in 2023, the WUE under the CK treatment was 2.61 kg·m−3, and the W2 treatment was slightly higher (+3.95%); in 2024, the WUE under the W3 treatment was the highest.

Figure 9.

Comparison of the yield and WUE of spring wheat under five water treatments with ND.

Under MD, the yield and WUE of the five water treatments are shown in Figure 10. The two-year data showed that the yield significantly decreased with the reduction in irrigation amount (p < 0.05). In 2023, the CK treatment (full irrigation) had the highest yield, and the W1–W4 treatments were 4.50–15.19% lower than CK, respectively; in 2024, the CK treatment still had the highest yield, and the W1–W4 treatments were 18.75–53.35% lower than CK, respectively. In terms of WUE, in 2023, the WUE under the CK treatment was the highest; in 2024, the W4 treatment had the highest WUE, 4.47% higher than CK.

Figure 10.

Comparison of the yield and WUE of spring wheat under five water treatments with MD.

From Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9, it can be seen that different water regulation methods (irrigation methods and irrigation amounts) had significantly different effects on spring wheat yield and WUE. FD had stably high yield and high WUE under moderate deficit (W1). The optimal irrigation amount for ND fluctuated interannually. MD is more sensitive to water, and full irrigation is more conducive to high yield. Moderate water deficit (non-full irrigation) could improve the WUE, but it needs to be adjusted in combination with irrigation methods. To be detailed, FD should adopt W1 (90% CK) while ND should adopt W2–W3 (70–80% CK). MD needs to carefully control the deficit degree. The responses of yield and WUE to the irrigation amount are affected by annual climate (such as precipitation). Thus, dynamic adjustment should be made in combination with the meteorological conditions of the current year in practical application.

4. Discussion

4.1. Correlation Between the Effects of Water Regulation on Spring Wheat Growth Phenotypes and Phenological Stages

The results of this study showed that the growth phenotypic indicators of spring wheat (LAI, SPAD, SD) were sensitive to water regulation and closely related to phenological stages. The jointing to heading stage was the critical period for the rapid growth of LAI and HC, while the filling stage was the important stage for SPAD and SD to reach their peaks. Water deficit significantly inhibited the maintenance of LAI and SPAD; especially in the late filling stage, leaf senescence was prominent. This is consistent with the study by Yang et al. (2023), which stated that water stress accelerates chlorophyll degradation and reduces leaf area [22]. The FD treatment could still maintain relatively high LAI and SPAD in the late filling stage, indicating that mulching delays leaf senescence by reducing soil evaporation and stabilizing root water supply. This is consistent with the conclusion of Wang Jingwei (2017) that film-mulched drip irrigation improves the root zone microenvironment [23].

Different water levels had significant effects on growth indicators: with the reduction in irrigation amount, LAI, SPAD, and SD all significantly decreased, while HC was less affected. This indicates that HC has strong adaptability to water stress, which may be related to the fact that spring wheat mainly undergoes stem elongation and panicle development after the jointing stage. This result is similar to the study on winter wheat by Song Wenpin et al. (2016), which showed that the effect of water deficit on plant height is smaller than that on the leaf area and biomass [24].

4.2. Regulatory Mechanism of Assimilate Translocation and Grain Filling on Yield

Yield formation is closely related to the processes of assimilate translocation and grain filling. In this study, the FD treatment under W1 had the highest yield, with significantly improved WUE. This indicates that moderate water deficit can optimize the distribution of photosynthetic products to grains, reduce vegetative growth redundancy, and increase the harvest index. This is consistent with the conclusion of Wen et al. (2017) in their study on spring wheat in arid areas, which pointed out that limited irrigation can increase the grain weight by promoting the translocation of assimilates to panicles during the filling stage [25]. On the contrary, severe water stress (W3, W4) led to insufficient grain filling and decreased 1000-grain weight, resulting in a significant reduction in yield. This phenomenon was more prominent under the MD treatment, indicating that shallow-buried drip irrigation has an unstable water supply in dry years, which affects grain plumpness.

4.3. Indicators of Water Use Efficiency and the Potential Role of Root Development

In this study, the WUE was calculated as the ratio of grain yield to total water consumption during the whole growth period, with specific indicators including the WUE values of each treatment (unit: kg·m−3). The results showed that moderate water deficit (such as W1 for FD, W2–W3 for ND) could significantly improve the WUE, which is consistent with the physiological mechanism that “water stress reduces luxurious transpiration”. In addition, the FD treatment (mulching treatment) showed obvious advantages in WUE in dry years (2024), indicating that water conservation measures are more effective in water-scarce environments.

The potential role of water regulation in root development and nutrient uptake should not be ignored. The FD treatment maintains soil water and temperature stability through mulching, which may promote root penetration and nutrient uptake, thereby improving water and nutrient use efficiency. This echoes the study on soil water distribution in the Shiyang River Basin by Li Wangcheng et al. (2007) [26]. Future studies can combine root sampling and nutrient determination to further reveal the interaction mechanism among water, roots, and yield.

4.4. Screening of Optimal Water Regulation Methods

Considering productivity and water use efficiency comprehensively, the film-mulched drip irrigation (FD) under W1 treatment (90% CK) achieved the optimal balance between yield and WUE, and showed a stable performance, especially in dry years or under moderate to severe water stress conditions. Non-mulched drip irrigation (ND) had more advantages under full irrigation (CK) or mild stress (W2–W3) in years with sufficient precipitation. However, non-mulched shallow-buried drip irrigation (MD) was sensitive to water, so the degree of water deficit needs to be carefully controlled. In practical applications, we recommend dynamically adjusting irrigation strategies according to the annual precipitation dynamics to achieve the goal of water conservation and high yield.

5. Conclusions

This study systematically evaluated the effects of three irrigation methods (film-mulched drip irrigation (FD), non-mulched drip irrigation (ND), and non-mulched shallow-buried drip irrigation (MD)) and five water treatments on the growth phenotypes, yield, and water use efficiency (WUE) of spring wheat through a two-year field experiment. The main conclusions are as follows:

The leaf area index (LAI), chlorophyll content (SPAD), and stem diameter (SD) of spring wheat all significantly decreased with the reduction in irrigation amount, while plant height (HC) was less affected by water regulation. In the late filling stage, film-mulched drip irrigation (FD) was significantly superior to non-mulched treatments in maintaining leaf function and stem development, with its advantages being more prominent especially under water stress conditions.

Yield and WUE were jointly affected by irrigation methods and interannual precipitation. Under moderate water deficit (W1, 90% CK), film-mulched drip irrigation (FD) could achieve the synergistic improvement of high yield and high WUE with strong stability; non-mulched drip irrigation (ND) performed better under full water supply or mild stress, but the interannual fluctuation of its optimal water threshold was relatively large; non-mulched shallow-buried drip irrigation (MD) was sensitive to water, with a significant yield decrease under severe water deficit.

Based on the above results, we recommend prioritizing the irrigation strategy of combining film-mulched drip irrigation (FD) with mild water deficit (W1 treatment) in spring wheat cultivation in arid regions of northwestern China to achieve the balance between water conservation and high yield. In practical applications, we suggest dynamically adjusting the irrigation frequency and amount according to the precipitation of the current year, with the jointing to filling stage as the key regulation period.

Future studies can further explore the mechanisms of different water regulation methods on the root development, nutrient uptake, and assimilate translocation of spring wheat and verify the applicability of this study in different ecological regions to promote the precise and regionalized application of water-saving irrigation technologies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.L. and P.Z.; Methodology, N.L., P.Z. and J.Z.; Data curation, P.Z.; Writing—review & editing, N.L.; Project administration, S.L.; Funding acquisition, S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFD1900801 and 2022YFC3002802) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52379052).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article. The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WUE | Water use efficiency |

| FD | Film-mulched drip irrigation |

| ND | Non-mulched drip irrigation |

| MD | Non-mulched shallow-buried drip irrigation |

| HC | Plant height |

| SD | Stem diameter |

| LAI | Leaf area index |

| SPAD | Chlorophyll content |

| LWC | Leaf water content |

References

- Zhang, K.; Wang, R.; Wang, H.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, F.; Yang, F.; Chen, F.; Qi, Y.; Lei, J. Influence of climate warming and rainfall reduction on semi-arid wheat production. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2019, 27, 413–421. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.L.; Liu, G.H.; Mai, X.F.; Xue, Y.X.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, S.Q. Comprehensive benefits evaluation of spring wheat multiple cropping forage grass in Ningxia Yellow River irrigation area. Agric. Res. Arid Areas 2022, 40, 50–60+103. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, D.; Sun, Y. Research and Development Status and Prospect of Wheat Germ Oil. Triticeae Crops 1999, 19, 58–60. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solovyov, O.; Shvidchenko, V.; Zaika, V.; Capo-Chichi, L.; Kadyrov, B. Spring Wheat Productivity and Profitability Under Various Crop Rotations in Northern Kazakhstan’s Chernozem. Int. J. Des. Nat. Ecodynamics 2024, 19, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K. Wheat: Chemistry and Technology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Chang, X.; Wang, D.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lv, B.; Ma, R.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, G.; et al. Effects of Black Soil and Alluvial Soil on Nutritional Quality of Different Spring Wheat. Crops 2017, 33, 84–90. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leklem, J.E.; Miller, L.T.; Perera, A.D.; Peffers, D.E. Bioavailability of vitamin B-6 from wheat bread in humans. J. Nutr. 1980, 110, 1819–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, Z.-H.; Li, F.-C.; Li, K.-Y.; Yang, N.; Yang, Y.-E. Contents of Protein and Amino Acids of Wheat Grain in Different Wheat Pro-duction Regions and Their Evaluation. Acta Agron. Sin. 2016, 42, 768–777. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Yan, S.; Wang, H.; Zhang, K.; Zhao, F.; Huang, X. Study on Gas Exchange Parameters and Water Use Efficiency of Spring Wheat Leaves Under Different Water Stress Levels. Arid Land Res. Manag. 2021, 38, 821–832. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, R.; Huang, X.; Wang, H. Effects of water and nitrogen deficit on yield and water use efficiency of spring wheat. Agric. Eng. 2024, 14, 115–120. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiyang River Basin Water Resources Bureau of Gansu Province. Shiyang River Basin: Comprehensive Management to Reconstruct the Order of Harmonious Coexistence between Humans and Water. China Water Resour. 2019, 66. (In Chinese) [CrossRef]

- Li, T. Pilot Study on Water Production Functions and Optimal Irrigation Schedule of Main Crops in Shinyang River Basin. Master’s Thesis, Northwest A&F University, Xianyang, China, 2005. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Zhang, E.; Wang, Q.; Wang, T.; Liu, C.; Yin, H.; Yu, H. Effect of irrigation and nitrogen supply levels on water consumption, grain yield and water use efficiency of spring wheat on notillage with stubble standing farmland. Acta Prataculturae Sin. 2012, 21, 169–177. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, Y.; Xu, C.; Yang, B.; Ha, R.; Xia, X.; Yang, G.; Ji, W.; Wang, H.; Yang, H.; et al. Comprehensive comparison experiment on different irrigation modes of spring wheat in the Yellow River Irrigation District of Ningxia. Agric. Technol. 2023, 43, 66–70. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, X.; Wei, G.; Xue, X.; Hao, W.; Wang, C.; Tan, J. Effects of nitrogen reduction and water saving on water consumption characteristics and water use efficiency of spring wheat in Ningxia Yellow River irrigation area. Agric. Res. Arid Areas 2024, 42, 150–160. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T. Study on Water and Nitrogen Use Characteristics of Spring Wheat and Their Interrelation. Master’s Thesis, Gansu Agricultural University, Lanzhou, China, 2009. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. Effects of Water Regulation in Growth Season on Growth and Water-Nitrogen Utilization of Spring Wheat in the Hexi Region. Master’s Thesis, Northwest A&F University, Xianyang, China, 2017. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Lv, Y.; Shao, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, R.; Gao, Q.; Han, H.; Liu, L. The Variations in Leaf-Level Photosynthesis and Intrinsic Water Use Efficiency of Different Spike Types Winter Wheat in North China. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2025, 211, e70091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, Z.; Bie, S.; Wang, R.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, Y.; He, F.; Jiang, G. Mild deficit irrigation delays flag leaf senescence and increases yield in drip-irrigated spring wheat by regulating endogenous hormones. J. Integr. Agric. 2025, 24, 2954–2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Gao, H.; Hu, B. The Research Progress of Farmland Water Ecological Process and Control. Anhui Agric. Sci. Bull. 2014, 20, 12–15. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, D.; Niu, J.; Du, T.; Kang, S. Improving subsurface soil moisture estimation using a 2-dimensional data assimilation framework incorporated with a dual state-parameter scheme. Water Resour. Res. 2024, 60, e2023WR035771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Li, S.; Wu, M.; Yang, H.; Zhang, W.; Chen, J.; Wang, C.; Huang, S.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, Y. Drip irrigation improves spring wheat water productivity by reducing leaf area while increasing yield. Eur. J. Agron. 2023, 143, 126710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. Effect of Mulched Drip Irrigation on Crop Root-Zone Soil Microenvironment and Crop Growth in Plastic Greenhouse. Doctoral Dissertation, Northwest A&F University, Xianyang, China, 2017. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Song, W.; Huang, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, L.; SUN, W.; Wang, Z.; Xue, X.; Guo, W.; Li, Y.; Chen, F. Effects of plastic film mulching and conventional irrigation on water consumption characteristics and yield of winter wheat. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2016, 24, 1445–1455. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Shang, S.; Yang, J. Optimization of irrigation scheduling for spring wheat with mulching and limited irrigation water in an arid climate. Agric. Water Manag. 2017, 192, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Feng, S.; Kang, S.; Du, T.; Chen, S. Distribution characteristics of soil water in desert oasis region in middle reaches of Shiyang River. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2007, 3, 138–143+157. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).