Research on Driving Forces of Spatiotemporal Patterns in Cotton Cultivation Considering Spatial Heterogeneity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Source

2.2.1. Satellite Data

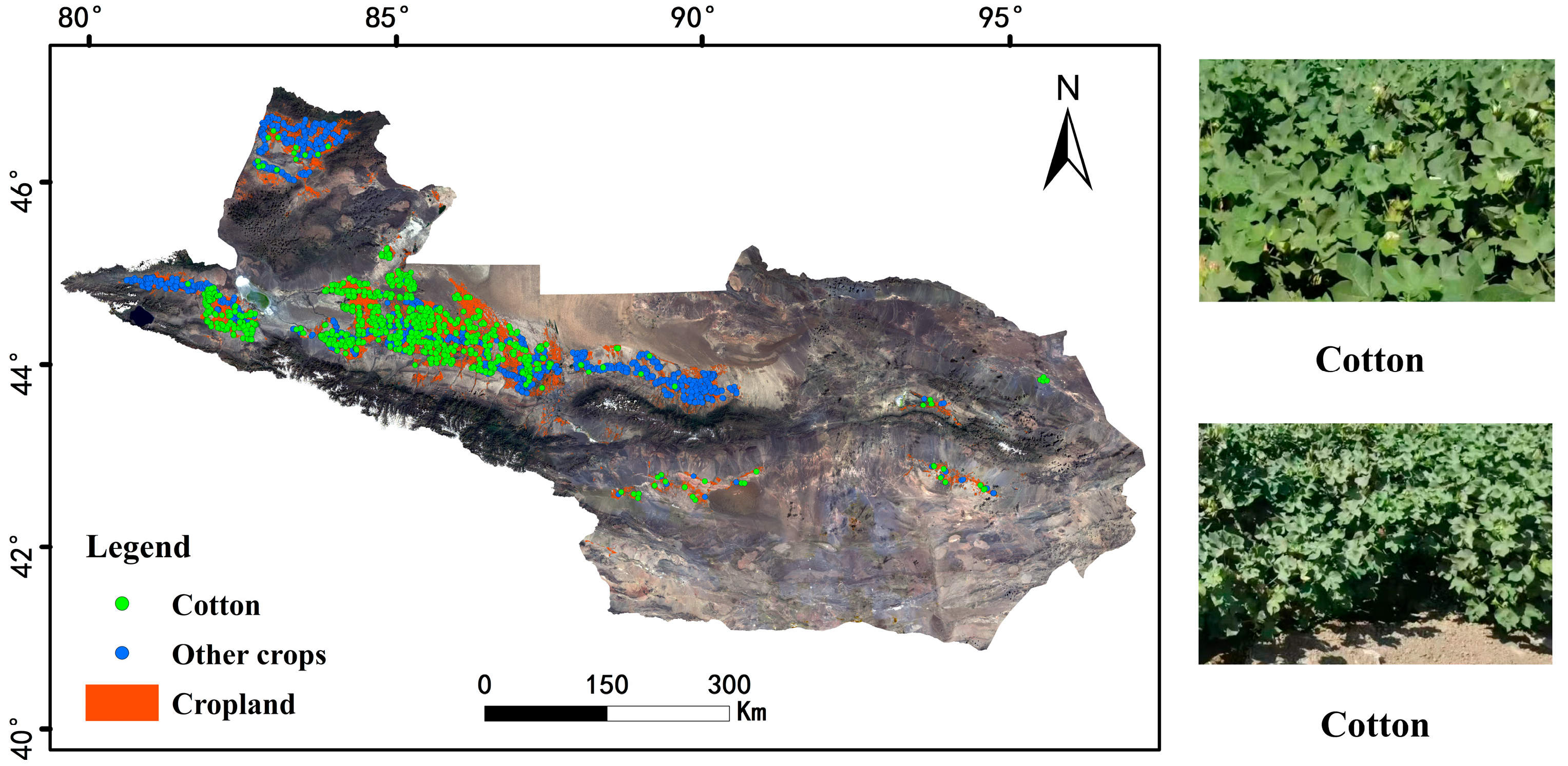

2.2.2. Sample Data

2.2.3. Factors Selected

2.2.4. Other Data

2.3. Methods

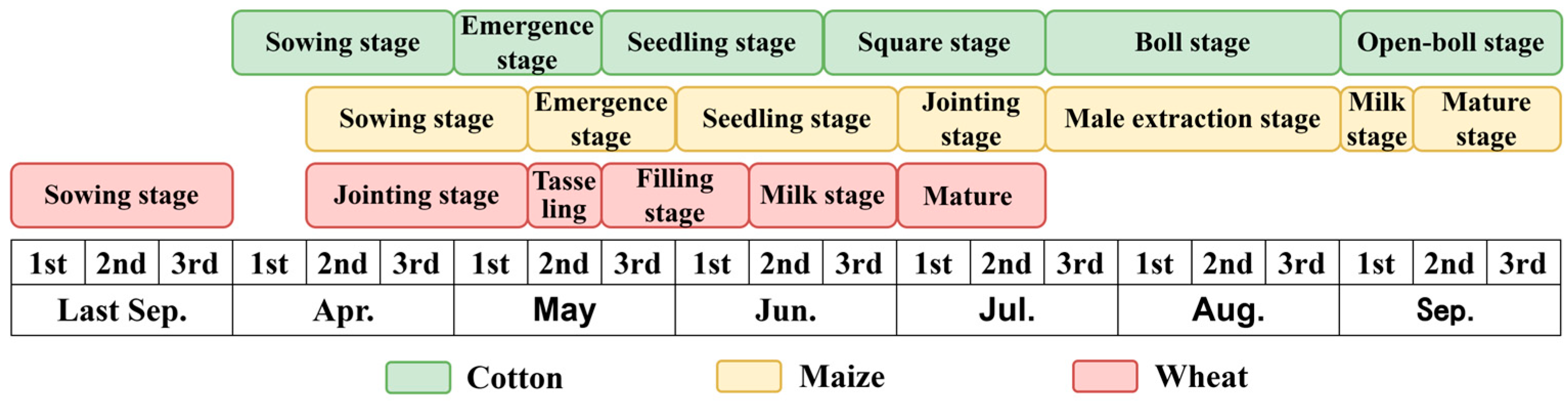

2.3.1. Remote Sensing Extraction of Cotton

2.3.2. Analytical Methods of Spatiotemporal Changes on Cotton Cultivation

2.3.3. Methods to Reveal Drivers of the Spatiotemporal Heterogeneity of Cotton Cultivation

3. Results

3.1. Accuracy of Remote Sensing Extraction for Cotton from 2000 to 2020

3.2. Spatiotemporal Variation Characteristics of Cotton Cultivation

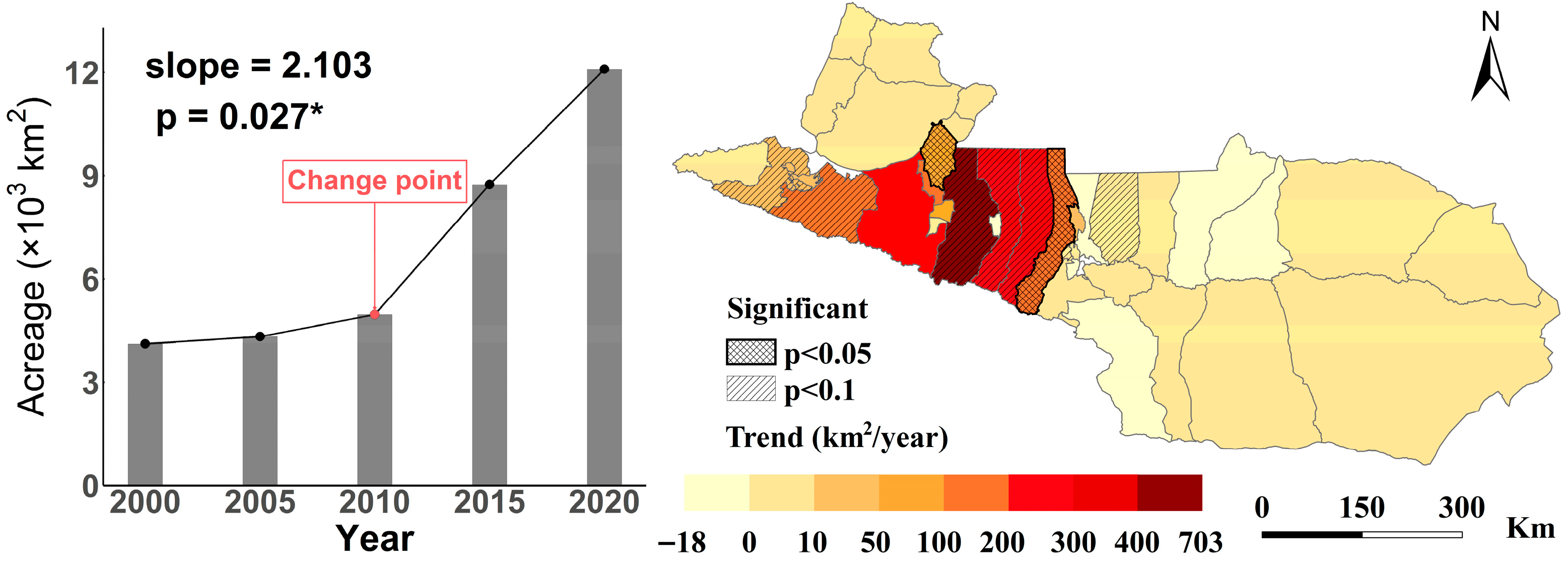

3.2.1. The Temporal Changes in Cotton

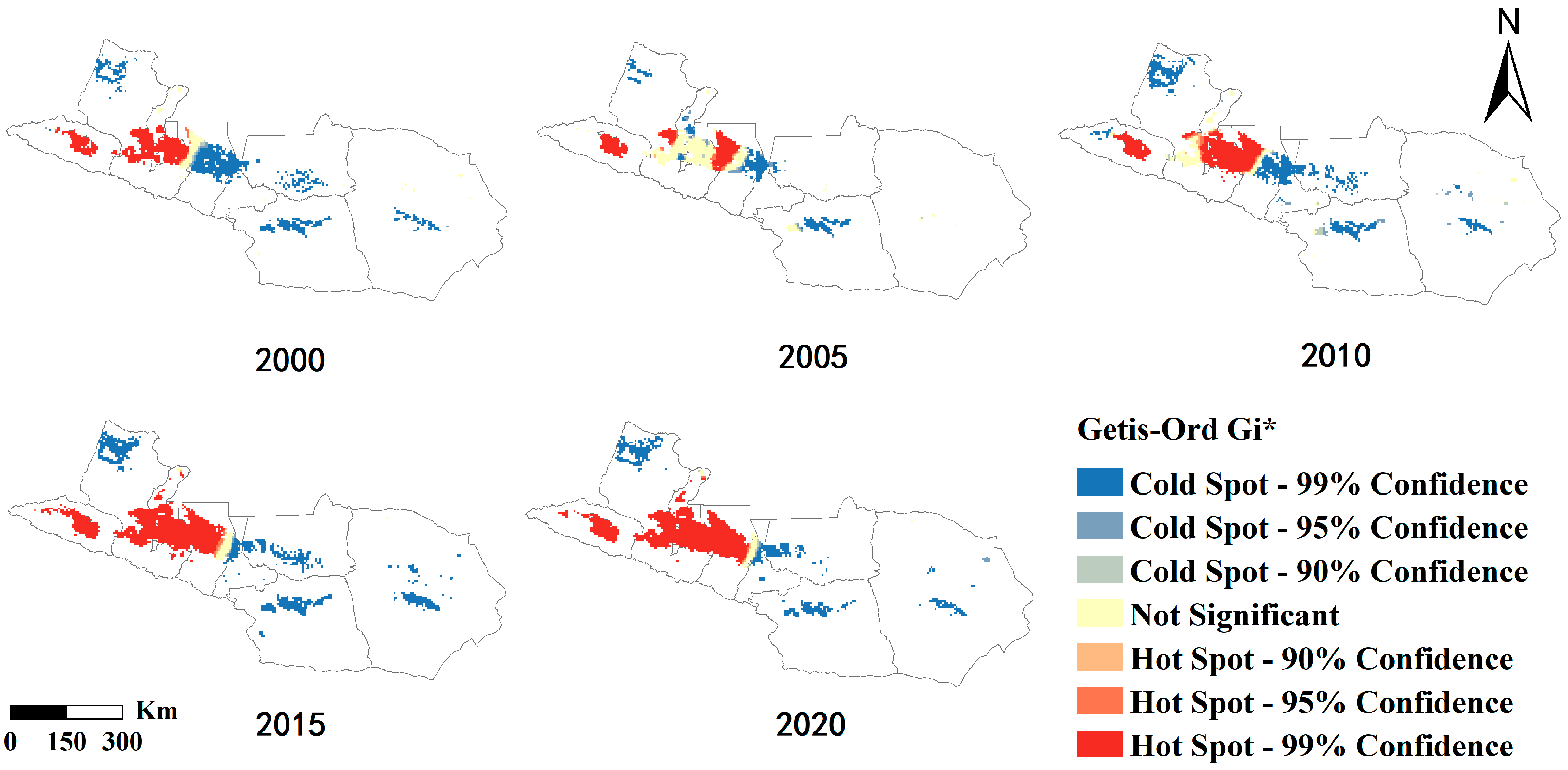

3.2.2. Spatial Variations in Cotton Cultivation

3.3. Drivers of Spatiotemporal Patterns for Cotton and Contributions of Relevant Factors

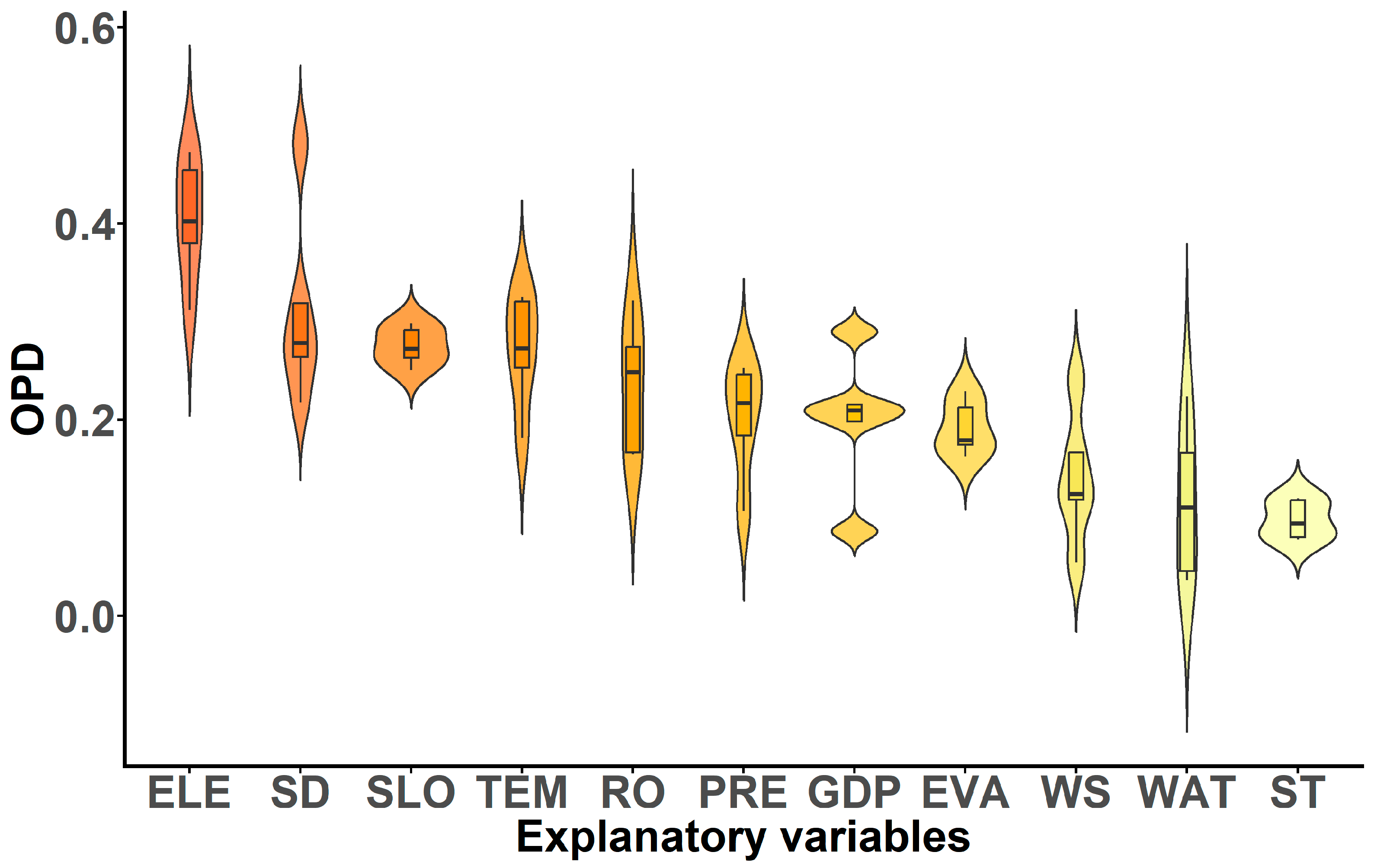

3.3.1. Impacts of Factors on Cotton Cultivation at the Global Scale

3.3.2. Impacts of the Interactions Between Pairwise Factors

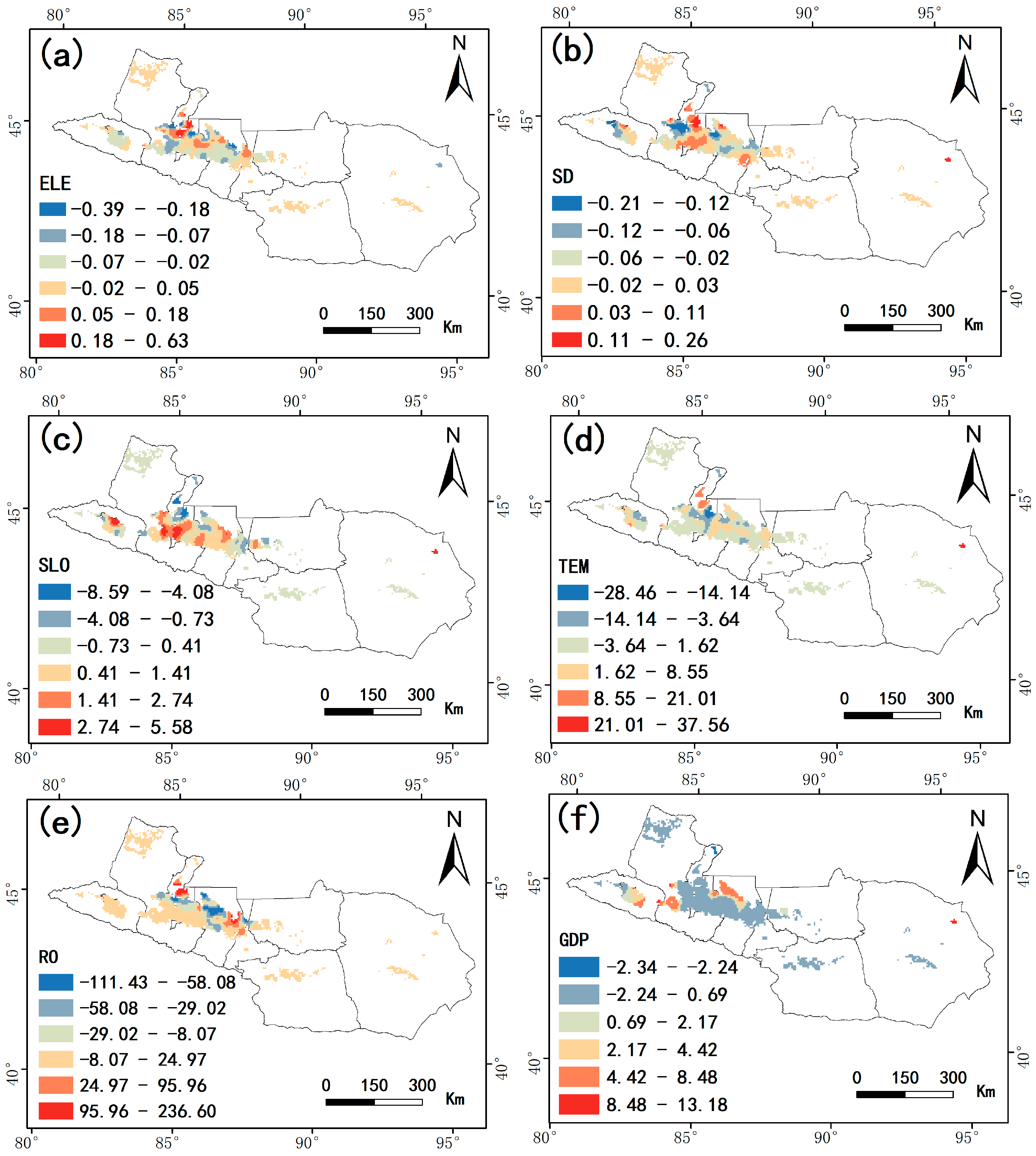

3.3.3. Key Factors Dominating Local Spatial Heterogeneity

4. Discussion

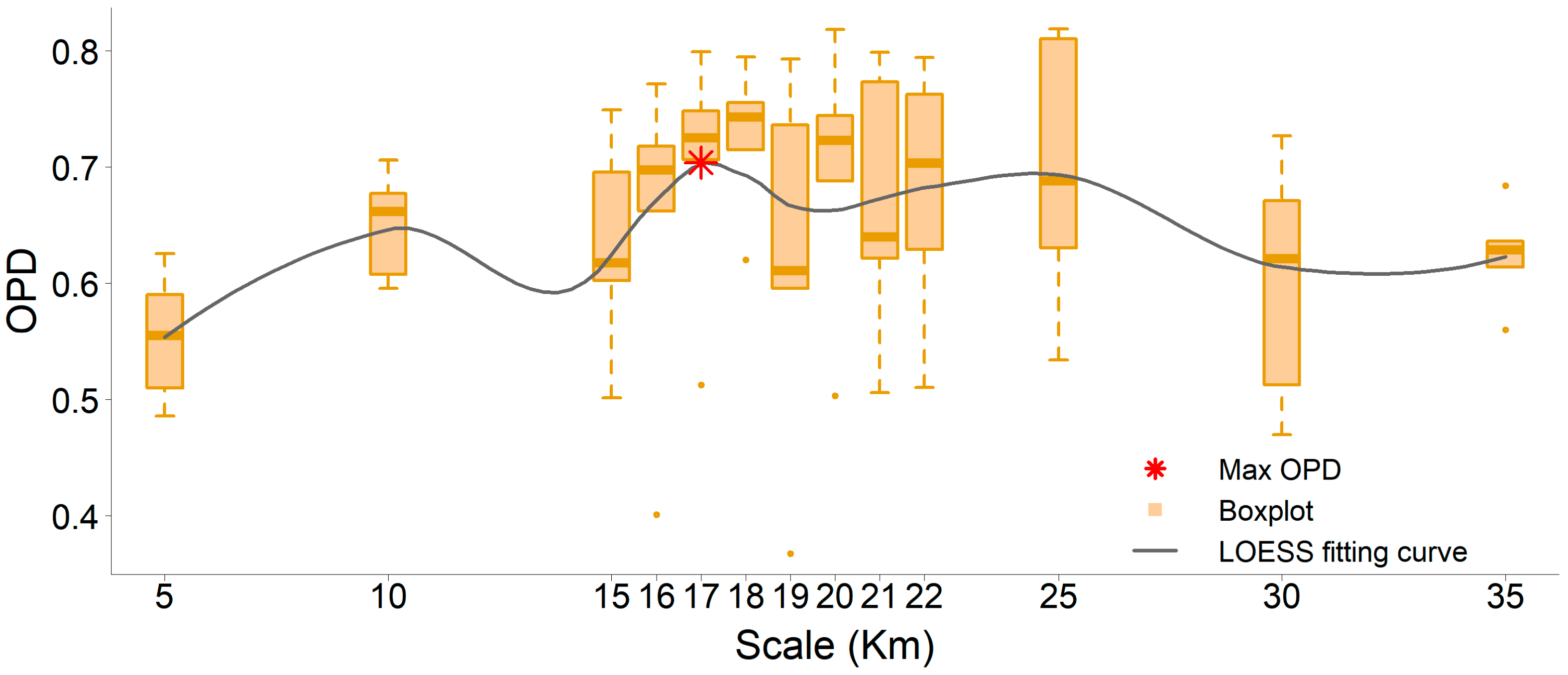

4.1. Spatial Scale Effects on Exploring for Drivers of Cotton Spatiotemporal Patterns

4.2. Interpretations of Driving Forces of Cotton Spatiotemporal Variability

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GWR | Geographically Weighted Regression method |

| SSH | Spatially stratified heterogeneity |

| PD | Power of determinants |

| OPD | Optimal power of determinants |

| GOZH | Geographically optimal zones-based heterogeneity |

| SHAP | Shapley Additive Explanations |

| LESH | Locally explained stratified heterogeneity model |

| SPD | SHAP power of determinants |

| NSTM | Northern slope of the Tianshan Mountains |

| TM | Thematic mapper |

| OLI | Operational land imager |

| RF | Random forest |

| GEE | Google Earth Engine |

| OA | Overall Accuracy |

| PA | Producer’s accuracy |

| UA | User’s Accuracy |

| MK | Mann–Kendall |

References

- USDA. Available online: https://apps.fas.usda.gov/psdonline/circulars/cotton.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Wang, Y.; Peng, S.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, L.; Zhao, W.; Qi, H.; Zhou, G.; Deng, N. Prospects for Cotton Self-Sufficiency in China by Closing Yield Gaps. Eur. J. Agron. 2022, 133, 126437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, X.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Wei, S. The Impact of Factor Price Change on China’s Cotton Production Pattern Evolution: Mediation and Spillover Effects. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Yu, J.; Li, S.; Liu, J.; Yang, G.; Wang, G.; Wang, J.; Song, N. Evolution of Crop Planting Structure in Traditional Agricultural Areas and Its Influence Factors: A Case Study in Alar Reclamation. Agronomy 2024, 14, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; He, Z.; He, D.; Xue, D.; Wang, Y.; Cao, S. Fractional Vegetation Coverage Response to Climatic Factors Based on Grey Relational Analysis during the 2000–2017 Growing Season in Sichuan Province, China. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2020, 41, 1170–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Li, J.; Li, Y. Spatiotemporal Characteristics and Driving Mechanisms of Arable Land in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region during 1990–2015. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2020, 70, 100720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Erion, G.; Chen, H.; DeGrave, A.; Prutkin, J.M.; Nair, B.; Katz, R.; Himmelfarb, J.; Bansal, N.; Lee, S.-I. From Local Explanations to Global Understanding with Explainable AI for Trees. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2020, 2, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhorst, J.P. Matlab Software for Spatial Panels. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 2014, 37, 389–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunsdon, C.; Fotheringham, A.S.; Charlton, M.E. Geographically Weighted Regression: A Method for Exploring Spatial Nonstationarity. Geogr. Anal. 1996, 28, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Wang, J.; Ge, Y.; Xu, C. An Optimal Parameters-Based Geographical Detector Model Enhances Geographic Characteristics of Explanatory Variables for Spatial Heterogeneity Analysis: Cases with Different Types of Spatial Data. GISci. Remote Sens. 2020, 57, 593–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, P.; Song, Y.; Huang, X.; Ma, H.; Liu, J.; Yao, Y.; Meng, L. Identifying Determinants of Spatio-Temporal Disparities in Soil Moisture of the Northern Hemisphere Using a Geographically Optimal Zones-Based Heterogeneity Model. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2022, 185, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapley, L.S. A Value for N-Person Games; RAND Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 1952; p. 295. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Luo, P.; Song, Y.; Zhang, L.; Qu, Y.; Hou, Z. A Locally Explained Heterogeneity Model for Examining Wetland Disparity. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2023, 16, 4533–4552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Wang, Y.; Mamtimin, A.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Gao, J.; Aihaiti, A.; Wen, C.; Song, M.; Yang, F.; et al. Simulation and Attribution Analysis of Spatial–Temporal Variation in Carbon Storage in the Northern Slope Economic Belt of Tianshan Mountains, China. Land 2024, 13, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Ma, H.; Fang, C. The Relationship Evolution between Urbanization and Urban Ecological Resilience in the Northern Slope Economic Belt of Tianshan Mountains, China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 97, 104783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, B.; Yang, G.; Du, Y.; Huang, H.; Wang, T.; Wang, J. Analysis of Spatiotemporal Evolution Patterns and Driving Forces of Reservoirs on the Northern Slope of the Tianshan Mountains in Xinjiang. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Fang, C.; Zhang, L. Analysis of the Coupling Coordinated Development of the Population–Water–Ecology–Economy System in Urban Agglomerations and Obstacle Factors Discrimination: A Case Study of the Tianshan North Slope Urban Agglomeration, China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 90, 104359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Lei, J.; Zhang, X.; Tong, Y.; Duan, Z.; Fan, L. Evolution of Economic Linkage Network of the Cities and Counties on the Northern Slope of the Tianshan Mountains, China. Reg. Sustain. 2023, 4, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xinjiang Scientific Expedition Data Sharing Service Platform. Available online: https://cstr.cn/CSTR:33110.11.XIEG.xjsedata.2022.00000095 (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Geospatial Data Cloud. Available online: http://www.gscloud.cn (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Copernicus Climate Data Store. Available online: https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Sun, W.; Shao, Q.; Liu, J.; Zhai, J. Assessing the Effects of Land Use and Topography on Soil Erosion on the Loess Plateau in China. CATENA 2014, 121, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Song, X.; Mu, X.; Gao, P.; Wang, F.; Zhao, G. Spatiotemporal Vegetation Cover Variations Associated with Climate Change and Ecological Restoration in the Loess Plateau. Agr. For. Meteorol. 2015, 209–210, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Mu, X.; Song, X.; Wu, D.; Cheng, A.; Qiu, B. Changes in Extreme Temperature and Precipitation Events in the Loess Plateau (China) during 1960–2013 under Global Warming. Atmos. Res. 2016, 168, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Fang, S.; Han, J. A Daily Sunshine Duration (SD) Dataset in China from Himawari AHI Imagery (2016–2023). Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2025, 17, 1427–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resource and Environmental Science Data Platform. Available online: https://www.resdc.cn/ (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Data Sharing and Service Portal. Available online: https://data.casearth.cn/ (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Agarwal, S.C. Gross Domestic Product & it’s Various Approaches. Int. J. Tax Econ. Manag. 2018, 1, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Platform for Common Geospatial Information Services. Available online: https://xinjiang.tianditu.gov.cn/ (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Xinjiang Scientific Expedition Data Sharing Service Platform. Available online: https://cstr.cn/CSTR:33110.11.XIEG.xjsedata.2022.00009105 (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Ok, A.O.; Akar, O.; Gungor, O. Evaluation of Random Forest Method for Agricultural Crop Classification. Eur. J. Remote Sens. 2012, 45, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NASA Shuttle Radar Topography Mission Global 1 arc Second V003 | NASA Earthdata. Available online: https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/data/catalog/lpcloud-srtmgl1-003 (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Metternicht, G. Vegetation Indices Derived from High-Resolution Airborne Videography for Precision Crop Management. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2003, 24, 2855–2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broge, N.H.; Leblanc, E. Comparing Prediction Power and Stability of Broadband and Hyperspectral Vegetation Indices for Estimation of Green Leaf Area Index and Canopy Chlorophyll Density. Remote Sens. Environ. 2001, 76, 156–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huete, A.; Justice, C.; Liu, H. Development of Vegetation and Soil Indices for MODIS-EOS. Remote Sens. Environ. 1994, 49, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roujean, J.-L.; Breon, F.-M. Estimating PAR Absorbed by Vegetation from Bidirectional Reflectance Measurements. Remote Sens. Environ. 1995, 51, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steven, M.D. The Sensitivity of the OSAVI Vegetation Index to Observational Parameters. Remote Sens. Environ. 1998, 63, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, B.; Yu, R.; Gao, A.; Bai, Y.; Yu, G. Interannual Dynamics and Driving Mechanisms of the Shrinkage for Lake Groups in the Jiziwan Region of Yellow River from 1986 to 2024. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 61, 102752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, P.K. Estimates of the Regression Coefficient Based on Kendall’s Tau. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1968, 63, 1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Ju, X.; Ding, J.; Wang, Y.; Shen, N.; Zhang, X.; Li, M. Understanding Water Yield Dynamics and Drivers in the Yellow River Basin Past Trends, Mechanisms, and Future Projections. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 505, 145441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Chen, Y.; Li, J.; Zhao, Y. Spatiotemporal Evolution and Driving Force Analysis of Drought Characteristics in the Yellow River Basin. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 170, 113007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Shu, B.; Amani-Beni, M.; Wei, D. Spatial Distribution Patterns of Rural Settlements in the Multi-Ethnic Gathering Areas, Southwest China: Ethnic Inter-Embeddedness Perspective. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 23, 372–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerri, G.; Crisci, A.; Congedo, L.; Munafò, M.; Morabito, M. A Functional Seasonal Thermal Hot-Spot Classification: Focus on Industrial Sites. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 151383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, P.; Xie, G.; Wang, W. Spatial Distribution Pattern of Aromia Bungii Within China and Its Potential Distribution Under Climate Change and Human Activity. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 14, e70520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, X.; Christakos, G.; Liao, Y.; Zhang, T.; Gu, X.; Zheng, X. Geographical Detectors-Based Health Risk Assessment and Its Application in the Neural Tube Defects Study of the Heshun Region, China. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2010, 24, 107–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Tang, Y.; Guo, J. Spatial Heterogeneity of Traditional Villages in Southern Sichuan, China: Insights from GWR and K-Means Clustering. Land 2025, 14, 1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Di, Q. Modifiable Areal Unit Problem and Environmental Factors of COVID-19 Outbreak. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 740, 139984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Xu, X.; Tan, Y.; Chen, M. Multi-Scalar Assessment of Ecosystem-Services Supply and Demand for Establishing Ecological Management Zoning. Appl. Geogr. 2024, 172, 103435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhu, Y.; Ma, Z.; He, J.; Guo, C.; Zhou, Q.; Song, L. Simulating the Impact of Climate Change on the Suitable Area for Cotton in Xinjiang Based on SDMs Model. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 227, 120750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Lin, H.; Wang, T.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, X.; Hu, X. Impact of Climate Change on Cotton Growth and Yields in Xinjiang, China. Field Crops Res. 2020, 247, 107590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zheng, B.; Luo, Q.; Jiao, W.; Yang, Y. Uncovering the Drivers and Regional Variability of Cotton Yield in China. Agriculture 2023, 13, 2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Sun, L.; Luo, Q.; Chen, H.; Yang, Y. Spatial Optimization of Cotton Cultivation in Xinjiang: A Climate Change Perspective. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2023, 124, 103523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, S.; He, X.; Wang, D.; Wu, D.; Tian, Z. Spatio-Temporal Changes and Its Driving Forces of Irrigation Water Requirements for Cotton in Xinjiang, China. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 280, 108218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number | Satellite | Time Phase | Range | Spatial Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Landsat-5 | September 2000, 2005, and 2010 | Study area | 30 m |

| 2 | Landsat-8 | September 2015 and 2020 | ||

| 3 | GF-1 | 2 September 2015, 10 September 2015 | Changji and Urumqi | 2/8 m |

| 4 | GF-2 | 9 May 2020, 2 August 2020, 16 August 2020 | Qitai County, Wenquan County and Shihezi City | 1/4 m |

| 5 | GeoEye-1 | 16 July 2010 | Shuanghe City | 0.41/1.64 m |

| 6 | QuickBird | 28 August 2002 17 May 2006 | Wujiaqu City and Hami City | 0.61/2.44 m |

| Category | Variable | Abbr. |

|---|---|---|

| Topography | Elevation | ELE |

| Slope | SLO | |

| Climate | Temperature | TEM |

| Precipitation | PRE | |

| Wind speed | WS | |

| Sunshine duration | SD | |

| Soil | Soil type | ST |

| Water resources | River network | WAT |

| Evaporation | EVA | |

| Runoff | RO | |

| Socio-economy | Gross domestic product | GDP |

| Year | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OA (%) | 92.75 | 94.01 | 91.30 | 92.54 | 92.93 |

| Kappa | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.86 | 0.89 | 0.89 |

| PA (%) | 96.00 | 97.08 | 94.76 | 98.72 | 94.81 |

| UA (%) | 87.80 | 91.71 | 90.79 | 97.48 | 92.80 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Du, M.; Shen, D.; Yang, X.; Lin, F.; Wu, C.; Zhang, D. Research on Driving Forces of Spatiotemporal Patterns in Cotton Cultivation Considering Spatial Heterogeneity. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2163. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15202163

Du M, Shen D, Yang X, Lin F, Wu C, Zhang D. Research on Driving Forces of Spatiotemporal Patterns in Cotton Cultivation Considering Spatial Heterogeneity. Agriculture. 2025; 15(20):2163. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15202163

Chicago/Turabian StyleDu, Meng, Deyu Shen, Xun Yang, Fenfang Lin, Chunfa Wu, and Dongyan Zhang. 2025. "Research on Driving Forces of Spatiotemporal Patterns in Cotton Cultivation Considering Spatial Heterogeneity" Agriculture 15, no. 20: 2163. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15202163

APA StyleDu, M., Shen, D., Yang, X., Lin, F., Wu, C., & Zhang, D. (2025). Research on Driving Forces of Spatiotemporal Patterns in Cotton Cultivation Considering Spatial Heterogeneity. Agriculture, 15(20), 2163. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15202163