Linking Yield, Baking Quality, and Rheological Properties to Guide Sustainable Improvement of Rwandan Wheat Varieties

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site and Sampling

2.2. Wheat Grain Yield and Quality Parameters Evaluation

2.2.1. Grain Yield

2.2.2. Wheat Flour Analysis: Protein Content, Gluten Composition, and Falling Number

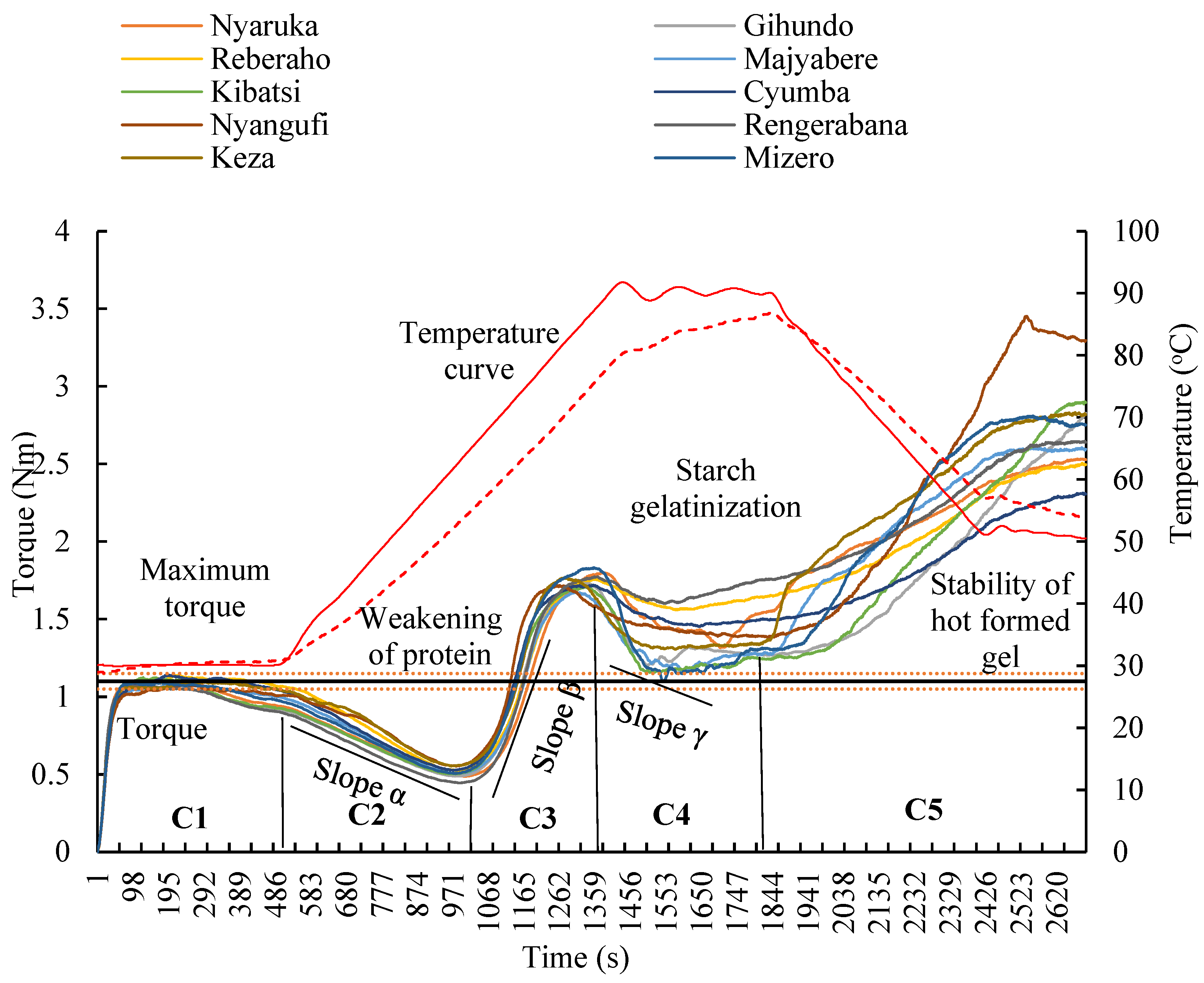

2.2.3. Mixolab Analyses

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

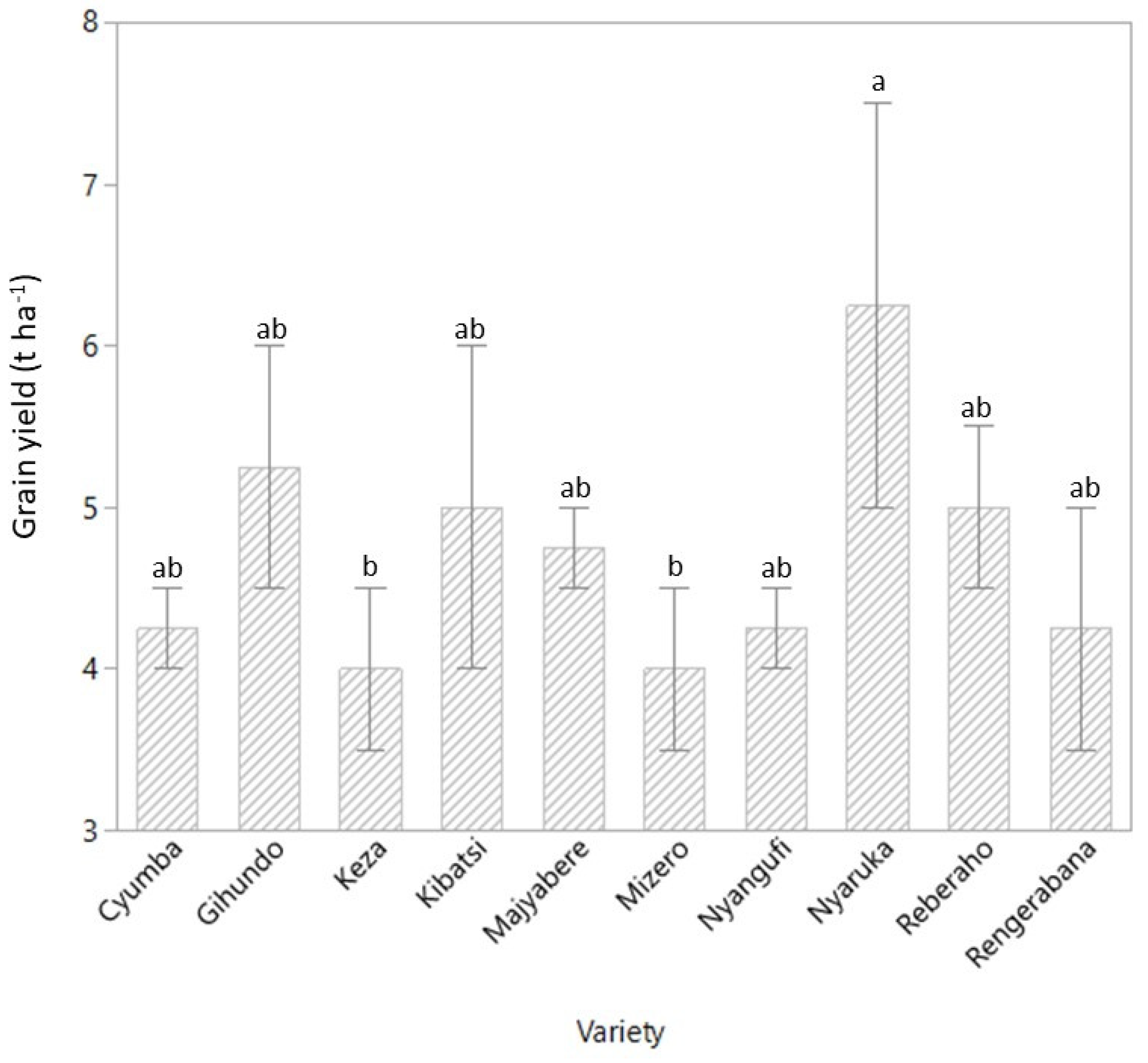

3.1. Grain Yield, Thousand Kernel Weight, and Hectoliter Weight

3.2. Wheat Flour Baking Quality Parameters

3.3. Dough Rheology

3.4. Regression Analysis Between Yield, Quality, and Rheological Parameters

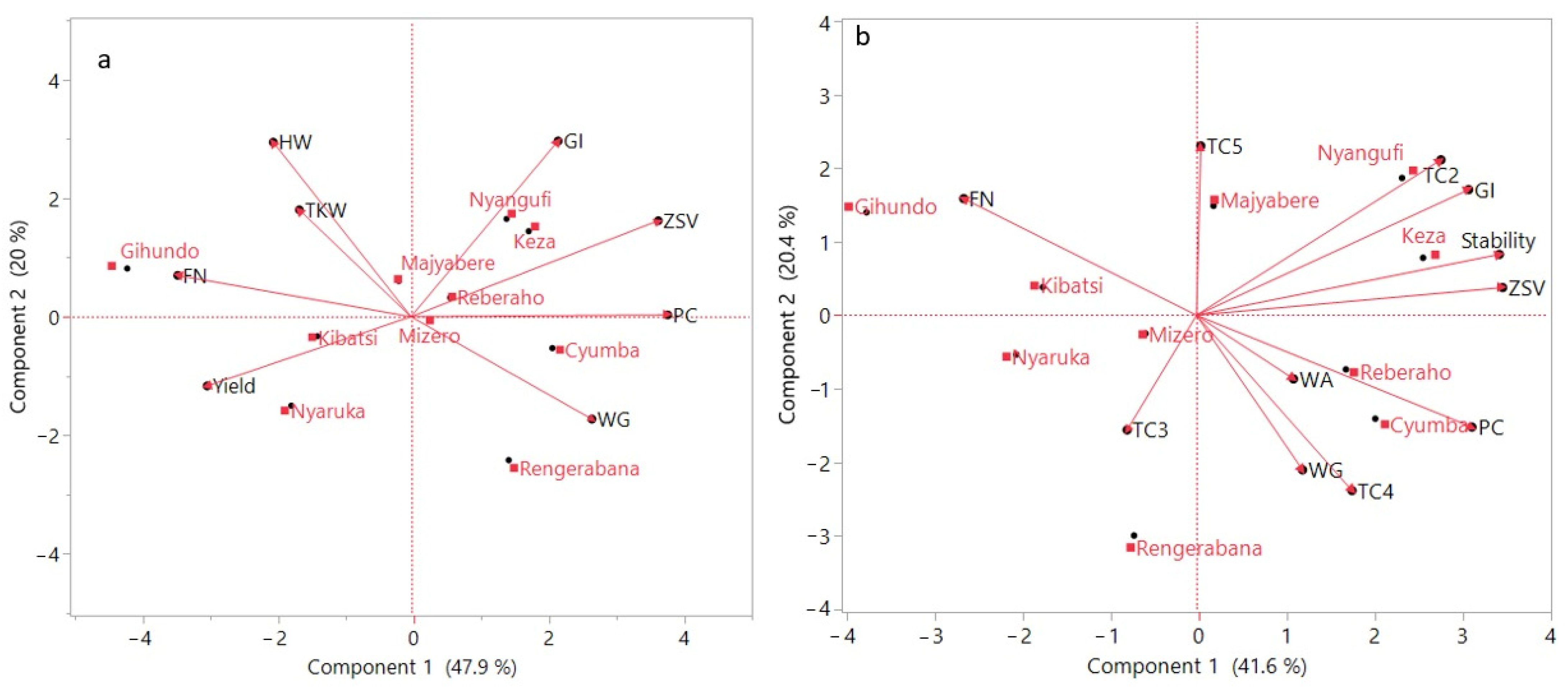

3.5. Principal Component Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Grain Yield and Yield Components

4.2. Baking Quality Parameters

4.3. Rheological Properties

4.4. Regression Analysis of Yield, Quality, and Rheological Parameters

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Levy, A.A.; Feldman, M. Evolution and Origin of Bread Wheat. Plant Cell 2022, 34, 2549–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, F.M.; Ahmad, I.; Butt, M.S.; Sheikh, M.A.; Pasha, I. Amino Acid Composition of Spring Wheats and Losses of Lysine during Chapati Baking. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2005, 18, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shewry, P.R.; Hey, S.J. The Contribution of Wheat to Human Diet and Health. Food Energy Secur. 2015, 4, 178–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiferaw, B.; Smale, M.; Braun, H.-J.; Duveiller, E.; Reynolds, M.; Muricho, G. Crops That Feed the World 10. Past Successes and Future Challenges to the Role Played by Wheat in Global Food Security. Food Sec. 2013, 5, 291–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqi, R.A.; Singh, T.P.; Rani, M.; Sogi, D.S.; Bhat, M.A. Diversity in Grain, Flour, Amino Acid Composition, Protein Profiling, and Proportion of Total Flour Proteins of Different Wheat Cultivars of North India. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, B.C.; Rajaram, S.; Gómez Macpherson, H. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (Eds.) Bread Wheat: Improvement and Production. In Plant Production and Protection Series; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2002; ISBN 978-92-5-104809-2. [Google Scholar]

- De Sousa, T.; Ribeiro, M.; Sabença, C.; Igrejas, G. The 10,000-Year Success Story of Wheat! Foods 2021, 10, 2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhang, P.; Yue, Y. Prediction of Global Wheat Cultivation Distribution under Climate Change and Socioeconomic Development. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 919, 170481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO. Crops and Livestock Products; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- USDA. USDA Wheat Outlook: Economic Research Service; WHS-25f 2025; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 2025.

- IGC International Grains Council. IGC International Grains Council Raises Global Wheat Production Forecast to 811 Mln Tons; IGC International Grains Council: London, UK, 2025.

- Awika, J.M. Major Cereal Grains Production and Use around the World. In ACS Symposium Series; Awika, J.M., Piironen, V., Bean, S., Eds.; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; Volume 1089, pp. 1–13. ISBN 978-0-8412-2636-4. [Google Scholar]

- Erenstein, O.; Jaleta, M.; Mottaleb, K.A.; Sonder, K.; Donovan, J.; Braun, H.-J. Global Trends in Wheat Production, Consumption and Trade. In Wheat Improvement; Reynolds, M.P., Braun, H.-J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 47–66. ISBN 978-3-030-90672-6. [Google Scholar]

- Ojha, S.; Karki, L.B. Forecasting Global Wheat Price in the Context of Changing Climate and Market Dynamics: An Application of SARIMA Modeling Technique. Am. J. Appl. Stat. Econ. 2025, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, P.A. Tripling Crop Yields in Tropical Africa. Nat. Geosci. 2010, 3, 299–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, D.K.; Mueller, N.D.; West, P.C.; Foley, J.A. Yield Trends Are Insufficient to Double Global Crop Production by 2050. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, N.M.; Jayne, T.S.; Shiferaw, B.A.; Mason, N.M.; Jayne, T.S.; Shiferaw, B.A. Wheat Consumption in Sub-Saharan Africa: Trends, Drivers, and Policy Implications; Department of Agricultural, Food, and Resource Economics, Department of Economics, Michigan State University: East Lansing, MI, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertassello, L.; Winters, P.; Müller, M.F. Access to Global Wheat Reserves Determines Country-Level Vulnerability to Conflict-Induced Ukrainian Wheat Supply Disruption. Nat. Food 2023, 4, 673–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Future Drivers of Growth in Rwanda: Innovation, Integration, Agglomeration, and Competition; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-1-4648-1280-4. [Google Scholar]

- Floride, M. Effect of Different Doses of Organic Fertilizers on Growth Characteristics and Yield of Wheat (Triticum aestivum). Diploma Thesis, Faculty of Agriculture, Busogo, Rwanda, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoema Corporation. Rwanda—Wheat Production Quantity. In The Wheat Production in Rwanda; Knoema Corporation: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Verhofstadt, E.; Maertens, M. Smallholder Cooperatives and Agricultural Performance in Rwanda: Do Organizational Differences Matter? Agric. Econ. 2014, 45, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyamweshi, A.R.; Nabahungu, N.L.; Mirali, J.C.; Kihara, J.; Oduor, G.; Rware, H.; Sileshi, G.W. Sustainable Intensification of Wheat Production under Smallholder Farming Systems in Burera, Musanze and Nyamagabe Districts of Rwanda. Ex. Agric. 2022, 58, e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MINAGRI. MINAGRI Annual Report 2023/2024; MINAGRI: Kigali, Rwanda, 2024.

- National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda. Rwanda Statistical Yearbook; National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda: Kigali, Rwanda, 2019.

- Baudron, F.; Ndoli, A.; Habarurema, I.; Silva, J.V. How to Increase the Productivity and Profitability of Smallholder Rainfed Wheat in the Eastern African Highlands? Northern Rwanda as a Case Study. Field Crops Res. 2019, 236, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndushabandi, E.N.S.; Rutayisire, C.; Mwangi, L.; Bizimana, V. Crop Intensification Program (CIP): Citizen’s Satisfaction Survey-2018; Institute of Research and Dialogue for Peace: Kigali, Rwanda, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Popkin, B.M. Urbanization, Lifestyle Changes and the Nutrition Transition. World Dev. 1999, 27, 1905–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, T.N.; Konvalina, P.; Kopecký, M.; Ghorbani, M.; Amirahmadi, E.; Bernas, J.; Ali, S.; Nguyen, T.G.; Murindangabo, Y.T.; Tran, D.K.; et al. Assessing Grain Yield and Achieving Enhanced Quality in Organic Farming: Efficiency of Winter Wheat Mixtures System. Agriculture 2023, 13, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazar, G. Wheat Flour Quality Assessment by Fundamental Non-Linear Rheological Methods: A Critical Review. Foods 2023, 12, 3353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koksel, H.; Kahraman, K.; Sanal, T.; Ozay, D.S.; Dubat, A. Potential Utilization of Mixolab for Quality Evaluation of Bread Wheat Genotypes. Cereal Chem. 2009, 86, 522–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torbica, A.; Drašković, M.; Tomić, J.; Dodig, D.; Bošković, J.; Zečević, V. Utilization of Mixolab for Assessment of Durum Wheat Quality Dependent on Climatic Factors. J. Cereal Sci. 2016, 69, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clay, D.C.; Dejaegher, Y.M.J. Agro-Ecological Zones: The Development of a Regional Classification. Tropicultura 1987, 5, 153–159. [Google Scholar]

- Rutebuka, J.; Kagabo, D.M.; Verdoodt, A. Farmers’ Diagnosis of Current Soil Erosion Status and Control within Two Contrasting Agro-Ecological Zones of Rwanda. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2019, 278, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, D.G. Developing Sustainable Wheat Production Systems: The Eighth Regional Wheat Workshop for Eastern, Central and Southern Africa; CIMMYT: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 1994; ISBN 978-92-9053-277-4. [Google Scholar]

- Van Ginkel, M.; Tanner, D.G. Canadian International Development Agency; International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (Eds.). In Proceedings of the Fifth Regional Wheat Workshop: For Eastern, Central, and Southern Africa and the Indian Ocean, Antsirabe, Madagascar, 5–10 October 1987; Centro Internacional de Mejoramiento de Maíz y Trigo: Texcoco, Mexico, 1988. ISBN 978-968-6127-03-4. [Google Scholar]

- Tanner, D.G. International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (Eds.). In Proceedings of the Sixth Regional Wheat Workshop for Eastern, Central and Southern Africa, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2–6 October 1989; International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT): Texcoco, Mexico, 1990. ISBN 978-968-6127-45-4. [Google Scholar]

- Lauro, A.O.; Paulo, H.C.; Man, M.K. New Microchondrometer to Measure Hectoliter Weight in Small Samples of Wheat. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2020, 15, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Fu, B.X. Inter-Relationships between Test Weight, Thousand Kernel Weight, Kernel Size Distribution and Their Effects on Durum Wheat Milling, Semolina Composition and Pasta Processing Quality. Foods 2020, 9, 1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhendi, A.; Ahmad, T.H.; Albayati, W.S.; Almukhtar, B.Q.; Ali, Z.K.; Al-Hayani, N.K. Comparisons between Flour Qualities Produced by Three Different Mills: Buhler, Quadrumat, and Industry Mills. Int. J. Food. Stud. 2022, 11, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, B.X.; Wang, K.; Dupuis, B.; Cuthbert, R.D. High Throughput Testing of Key Wheat Quality Traits in Hard Red Spring Wheat Breeding Programs. In Wheat Quality for Improving Processing and Human Health; Igrejas, G., Ikeda, T.M., Guzmán, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 309–321. ISBN 978-3-030-34162-6. [Google Scholar]

- ICC Standard No. 137/1; Mechanical Determination of the Wet Gluten Content of Wheat Flour (Glutomatic). International Association for Cereal Science and Technology: Vienna, Austria, 1994. Available online: https://icc.or.at/store/137-1-mechanical-determination-of-the-wet-gluten-content-of-wheat-flour-glutomatic-pdf (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- ICC Standard No. 107/1; Determination of the “Falling Number” According to Hagberg-Perten as a Measure of the Degree of Alpha-Amylase Activity in Grain and Flour. International Association for Cereal Science and Technology: Vienna, Austria, 1995. Available online: https://icc.or.at/store/107-1-determination-of-the-falling-number-according-to-hagberg-perten-as-a-measure-of-the-degree-of-alpha-amylase-activity-in-grain-and-flour-pdf (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- AACC International. Approved Methods of Analysis—Method 56-81.03—Determination of Falling Number, 11th ed.; AACC International: St. Paul, MN, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushuk, W.; Rasper, V.F. Wheat: Production, Properties and Quality; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1994; ISBN 978-1-4615-2672-8. [Google Scholar]

- Konvalina, P.; Grausgruber, H.; Dang, K.T.; Vlasek, O.; Capouchova, I.; Sterba, Z.; Suchy, K.; Stolickova, M.; Kyptova, M.; Bernas, J.; et al. Rheological and Technological Quality of Minor Wheat Species and Common Wheat. In Wheat Improvement, Management and Utilization; Wanyera, R., Owuoche, J., Eds.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2017; ISBN 978-953-51-3151-9. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, K.D.; Konvalina, P.; Capouchova, I.; Janovska, D.; Lacko-Bartosova, M.; Kopecky, M.; Tran, P.X.T. Comparative Study on Protein Quality and Rheological Behavior of Different Wheat Species. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICC Standard No. 116/1; Determination of Sedimentation Value (According to Zeleny) as an Approximate Measure of Baking Quality (Approved 1972; Revised 1994). International Association for Cereal Science and Technology: Vienna, Austria, 1994. Available online: https://icc.or.at/store/116-1-determination-of-sedimentation-value-according-to-zeleny-as-an-approximate-measure-of-baking-quality-pdf (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- ICC Standard No. 173; Whole Meal and Flour from T. Aestivum—Determination of Rheological Behavior as a Function of Mixing and Temperature Increase. International Association for Cereal Science and Technology: Vienna, Austria, 2011. Available online: https://icc.or.at/store/173-whole-meal-and-flour-from-t-aestivum-determination-of-rheological-behavior-as-a-function-of-mixing-and-temperature-increase-pdf (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Dubat. A New AACC International Approved Method to Measure Rheological Properties of a Dough Sample. Cereal Foods World 2010, 55, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanyera, R. Wheat Improvement, Management and Utilization; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2017; ISBN 978-953-51-3152-6. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Ambrona, C.G.H.; Maletta, E. Achieving Global Food Security through Sustainable Development of Agriculture and Food Systems with Regard to Nutrients, Soil, Land, and Waste Management. Curr. Sustain. Renew. Energy Rep. 2014, 1, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, T.; Byerlee, D.; Edmeades, G. Crop Yields and Global Food Security: Will Yield Increase Continue to Feed the World? ACIAR Monograph Series; ACIAR: Canberra, Australia, 2014; ISBN 978-1-925133-05-9. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.K.; Marshall, F.; Dawson, N.M. Revisiting Rwanda’s Agricultural Intensification Policy: Benefits of Embracing Farmer Heterogeneity and Crop-Livestock Integration Strategies. Food Sec. 2022, 14, 637–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsabimana, A.; Niyitanga, F.; Weatherspoon, D.D.; Naseem, A. Land Policy and Food Prices: Evidence from a Land Consolidation Program in Rwanda. J. Agric. Food Ind. Organ. 2021, 19, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hilfy, I.H.; Wahid, S.A.; Al-Abodi, H.M.K.; Al-Salmani, S.A.A.; Mahamud, M.R.; Hossain, M.B. Grain Yield and Quality of Wheat as Affected by Cultivars and Seeding Rates. Malays. J. Sustain. Agric. 2019, 3, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, T.N.; Kopecký, M.; Konvalina, P. Winter Wheat Mixtures Influence Grain Rheoogical and Mixolab Quality. J. Appl. Life Sci. Environ. 2022, 54, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konvalina, P.; Stehno, Z.; Capouchova, I.; Moudry, J. Wheat Growing and Quality in Organic Farming. In Research in Organic Farming; Nokkoul, R., Ed.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2011; ISBN 978-953-307-381-1. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Li, C.; Yang, J.; Li, Z.; Wang, X.; Guo, Z.; Tian, Y.; Liu, J.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, D. Integrating Crop and Soil Nutrient Management for Higher Wheat Grain Yield and Protein Concentration in Dryland Areas. Eur. J. Agron. 2023, 147, 126827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitura, K.; Cacak-Pietrzak, G.; Feledyn-Szewczyk, B.; Szablewski, T.; Studnicki, M. Yield and Grain Quality of Common Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Depending on the Different Farming Systems (Organic vs. Integrated vs. Conventional). Plants 2023, 12, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, M.; Bonnett, D.; Chapman, S.C.; Furbank, R.T.; Manès, Y.; Mather, D.E.; Parry, M.A.J. Raising Yield Potential of Wheat. I. Overview of a Consortium Approach and Breeding Strategies. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khazaei, F.; AghaAlikhani, M.; Mobasser, S.; Mokhtassi-Bidgoli, A.; Asharin, H.; Sadeghi, H. Evaluation of Wheat (Triticum Aestivum, L.) Seed Quality of Certified Seed and Farm-Saved Seed in Three Provinces of Iran. Plant Breed. Seed Sci. 2016, 73, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zheng, B.; He, Y. Improving Grain Yield via Promotion of Kernel Weight in High Yielding Winter Wheat Genotypes. Biology 2021, 11, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botwright, T.L.; Condon, A.G.; Rebetzke, G.J.; Richards, R.A. Field Evaluation of Early Vigour for Genetic Improvement of Grain Yield in Wheat. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 2002, 53, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Zhou, L.; Chen, J.; Qiu, Z.; He, Y. GainTKW: A Measurement System of Thousand Kernel Weight Based on the Android Platform. Agronomy 2018, 8, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, M.; Sagoo, A.; Khan, E.A.; Ghaffar, A.; Hussain, N.; Irshad, M.; Khaliq, M.; Abbas, M. Comparison of Yield and Yield Related Traits of Spring Wheat Varieties to Various Seed Rates. Int. J. Biosci. 2018, 12, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvnjak, J.; Katanic, Z.; Sarcevic, H.; Spanic, V. Analysis of the Photosynthetic Parameters, Grain Yield, and Quality of Different Winter Wheat Varieties over a Two-Year Period. Agronomy 2024, 14, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majidi, M. Evaluation of Yield and Yield Components of New Wheat Cultivars in Comparison with Sardari Wheat. Plant Prod. Genet. 2019, 1, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, W.; Gong, X.; Ibba, M.I.; Govindan, V.; Cao, S.; Liu, J.; He, Z. Variation of the Ferulic Acid Concentration and Kernel Weight in CIMMYT Bread Wheat Germplasm and Selection of Lines for Functional Food Production. LWT 2024, 195, 115829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manley, M.; Engelbrecht, M.L.; Williams, P.C.; Kidd, M. Assessment of Variance in the Measurement of Hectolitre Mass of Wheat, Using Equipment from Different Grain Producing and Exporting Countries. Biosyst. Eng. 2009, 103, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mut, Z.; Aydin, N.; Bayramoglu, H.O.; Ozcan, H. Stability of Some Quality Traits in Bread Wheat (Triticum aestivum) Genotypes. J. Env. Biol. 2010, 31, 489–495. [Google Scholar]

- Chewaka, N.; Estifanos, E.; Galeta, N. Genetic Variability in Bread Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Genotypes under Irrigated Condition. Curr. Agric. Res. J. 2024, 12, 658–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobocha, D.; Negasa, G.; Abera, G. Interactive Effects of Location and N- Fertilizer Rates on Grain Quality Traits of Bread Wheat Varieties at Arsi Zone, South-Eastern Ethiopia. J. Chem. Environ. Biol. Eng. 2024, 8, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Torres, E.; Argumedo-Macías, A.; Bernal-Muñoz, R.; Cepeda-Cornejo, V.; Taboada-Gaytán, O.R. Peso Hectolítrico y Peso de Semilla Predicen El Volumen de Reventado En Amaranto. Remexca 2023, 14, e3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüy, M.; Türk, F.; Argun, M.Ş.; Polat, T. Investigation of the Effect of Hectoliter and Thousand Grain Weight on Variety Identification in Wheat Using Deep Learning Method. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2023, 102, 102116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacko-Bartošová, M.; Lacko-Bartošová, L.; Konvalina, P. Wheat Rheological and Mixolab Quality in Relation to Cropping Systems and Plant Nutrition Sources. Czech J. Food Sci. 2021, 39, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wysocka, K.; Cacak-Pietrzak, G.; Feledyn-Szewczyk, B.; Studnicki, M. The Baking Quality of Wheat Flour (Triticum aestivum L.) Obtained from Wheat Grains Cultivated in Various Farming Systems (Organic vs. Integrated vs. Conventional). Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacko-Bartošová, M.; Konvalina, P.; Lacko-Bartošová, L. Baking Quality Prediction of Spelt Wheat Based on Rheological and Mixolab Parameters. Acta Aliment. 2019, 48, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoune Liliane, T.; Shelton Charles, M. Factors Affecting Yield of Crops. In Agronomy—Climate Change and Food Security; Amanullah, Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020; ISBN 978-1-83881-222-5. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, J.V.; Jaleta, M.; Tesfaye, K.; Abeyo, B.; Devkota, M.; Frija, A.; Habarurema, I.; Tembo, B.; Bahri, H.; Mosad, A.; et al. Pathways to Wheat Self-Sufficiency in Africa. Glob. Food Secur. 2023, 37, 100684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.; Shewry, P.R. (Eds.) Wheat: Chemistry and Technology, 4th ed.; AACC International: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-1-891127-55-7. [Google Scholar]

- Ortolan, F.; Steel, C.J. Protein Characteristics That Affect the Quality of Vital Wheat Gluten to Be Used in Baking: A Review. Comp. Rev. Food Sci. Food Safe 2017, 16, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tronsmo, K.M.; Færgestad, E.M.; Schofield, J.D.; Magnus, E.M. Wheat Protein Quality in Relation to Baking Performance Evaluated by the Chorleywood Bread Process and a Hearth Bread Baking Test. J. Cereal Sci. 2003, 38, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyeyinka, S.A.; Bassey, I.-A.V. Composition, Functionality, and Baking Quality of Flour from Four Brands of Wheat Flour. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2023, 23, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Garg, S.; Sheikh, I.; Vyas, P.; Dhaliwal, H.S. Effect of Wheat Grain Protein Composition on End-Use Quality. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, 2771–2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, C.; Ibba, M.I.; Álvarez, J.B.; Sissons, M.; Morris, C. Wheat Quality. In Wheat Improvement: Food Security in a Changing Climate; Reynolds, M.P., Braun, H.-J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 177–193. ISBN 978-3-030-90673-3. [Google Scholar]

- Oikonomou, N.A.; Bakalis, S.; Rahman, M.S.; Krokida, M.K. Gluten Index for Wheat Products: Main Variables in Affecting the Value and Nonlinear Regression Model. Int. J. Food Prop. 2015, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiefenbacher, K.F. The Technology of Wafers and Waffles; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-0-12-809438-9. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, N.M.; Gianibelli, M.C.; McCaig, T.N.; Clarke, J.M.; Ames, N.P.; Larroque, O.R.; Dexter, J.E. Relationships between Dough Strength, Polymeric Protein Quantity and Composition for Diverse Durum Wheat Genotypes. J. Cereal Sci. 2007, 45, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Kovacs, M.I.P. Swelling Index of Glutenin Test. II. Application in Prediction of Dough Properties and End-Use Quality. Cereal Chem. 2002, 79, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veraverbeke, W.S.; Delcour, J.A. Wheat Protein Composition and Properties of Wheat Glutenin in Relation to Breadmaking Functionality. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2002, 42, 179–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Violeta, I.; Georgeta, S.; Ina, V.; Aprodu, I.; Banu, I. Comparative Evaluation of Wet Gluten Quantity and Quality through Different Methods. Ann. Univ. Dunarea Jos Galati. Fascicle VI-Food Technol. 2010, 34, 49–53. [Google Scholar]

- Bodor, K.; Szilágyi, J.; Salamon, B.; Szakács, O.; Bodor, Z. Physical–Chemical Analysis of Different Types of Flours Available in the Romanian Market. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Džafić, A.; Mulić, J.; Akagić, A.; Oručević Žuljević, S. Effects of Wet Gluten Adjustment on Physico-Chemical and Rheological Characteristics of Three Types of Wheat Flour. In Proceedings of the 10th Central European Congress on Food, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 11–13 June 2020; Brka, M., Sarić, Z., Oručević Žuljević, S., Omanović-Mikličanin, E., Taljić, I., Biber, L., Mujčinović, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 211–222. ISBN 978-3-031-04796-1. [Google Scholar]

- Sulek, A.; Cacak-Pietrzak, G. The Influence of Production Technology on Yield and Selected Quality Parameters of Spring Wheat Cultivars. Res. Rural Dev. 2018, 2, 42–48. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, D.K. Research on the Agronomic and Quality Characteristics of Modern Wheat Cultivars in Organic Farming. Ph.D. Thesis, University of South Bohemia in Ceske Budejovice, České Budějovice, Czechia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi, H.; Mirseyed Hosseini, H.; Moshiri, F.; Alikhani, H.A.; Etesami, H. Impact of Varied Tillage Practices and Phosphorus Fertilization Regimes on Wheat Yield and Grain Quality Parameters in a Five-Year Corn-Wheat Rotation System. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 14717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsenov, N.; Gubatov, T.; Yanchev, I. Environment- and Genotype-Dependent Stability in the Common Wheat Grain Quality (Triticum aestivum L.). Int. J. Innov. Approaches Agric. Res. 2023, 7, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiszonas, A.M.; Engle, D.A.; Pierantoni, L.A.; Morris, C.F. Relationships between Falling Number, A-amylase Activity, Milling, Cookie, and Sponge Cake Quality of Soft White Wheat. Cereal Chem. 2018, 95, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jańczak-Pieniążek, M.; Buczek, J.; Kaszuba, J.; Szpunar-Krok, E.; Bobrecka-Jamro, D.; Jaworska, G. A Comparative Assessment of the Baking Quality of Hybrid and Population Wheat Cultivars. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ral, J.; Whan, A.; Larroque, O.; Leyne, E.; Pritchard, J.; Dielen, A.; Howitt, C.A.; Morell, M.K.; Newberry, M. Engineering High A-amylase Levels in Wheat Grain Lowers Falling Number but Improves Baking Properties. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2016, 14, 364–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jukić, M.; Šumanovac, F.; Nakov, G.; Šimić, G.; Komlenić, D.K.; Ivanova, N.; Lukinac, J. Application of the Falling Number Method in the Evaluation of the α-Amylase Activity of Malt Flour. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moot, D.J.; Every, D. A Comparison of Bread Baking, Falling Number, α-Amylase Assay and Visual Method for the Assessment of Pre-Harvest Sprouting in Wheat. J. Cereal Sci. 1990, 11, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zecevic, V.; Knezevic, D.; Boskovic, J.; Micanovic, D.; Dozet, G. Effect of Nitrogen Fertilization on Winter Wheat Quality. Cereal Res. Commun. 2010, 38, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaka, V.; Gulia, N.; Khatkar, B.S. Application of Mixolab to Assess the Bread Making Quality of Wheat Varieties. Open Access Sci. Rep. 2012, 183, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, B.; Amend, T.; Belitz, H.-D. The Course of the SDS and Zeleny Sedimentation Tests for Gluten Quality and Related Phenomena Studied Using the Light Microscope. Z. Leb. Unters. Forch 1993, 196, 122–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrušková, M.; Faměra, O. Prediction of Wheat and Flour Zeleny Sedimentation Value Using NIR Technique. Czech J. Food Sci. 2003, 21, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surma, M.; Adamski, T.; Banaszak, Z.; Kaczmarek, Z.; Kuczyńska, H.; Majcher, M.; Ługowska, B.; Obuchowskił, W.; Salmanowicz, B.; Krystkowiak, K. Effect of Genotype, Environment and Their Interaction on Quality Parameters of Wheat Breeding Lines of Diverse Grain Hardness. Plant Prod. Sci. 2012, 15, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigalli, G. Study of Zeleny’s sedimentation test as an index for classification of wheat and flour and its use in Ecuador. Rev. Ecuat. Hig. Med. Trop. 1958, 15, 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Colombo, A.; Pérez, G.T.; Ribotta, P.D.; León, A.E. A Comparative Study of Physicochemical Tests for Quality Prediction of Argentine Wheat Flours Used as Corrector Flours and for Cookie Production. J. Cereal Sci. 2008, 48, 775–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zecevic, V.; Boskovic, J.; Knezevic, D.; Micanovic, D. Effect of Seeding Rate on Grain Quality of Winter Wheat. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 2014, 74, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shewry, P.R.; Halford, N.G. Cereal Seed Storage Proteins: Structures, Properties and Role in Grain Utilization. J. Exp. Bot. 2002, 53, 947–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiszonas, A.M.; Morris, C.F. Wheat Breeding for Quality: A Historical Review. Cereal Chem. 2018, 95, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Würschum, T.; Leiser, W.L.; Kazman, E.; Longin, C.F.H. Genetic Control of Protein Content and Sedimentation Volume in European Winter Wheat Cultivars. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2016, 129, 1685–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rharrabti, Y.; Villegas, D.; Garcia Del Moral, L.F.; Aparicio, N.; Elhani, S.; Royo, C. Environmental and Genetic Determination of Protein Content and Grain Yield in Durum Wheat under Mediterranean Conditions. Plant Breed. 2001, 120, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muqaddasi, Q.H.; Muqaddasi, R.K.; Ebmeyer, E.; Korzun, V.; Argillier, O.; Mirdita, V.; Reif, J.C.; Ganal, M.W.; Röder, M.S. Genetic Control and Prospects of Predictive Breeding for European Winter Wheat’s Zeleny Sedimentation Values and Hagberg-Perten Falling Number. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2023, 136, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Della Valle, G.; Dufour, M.; Hugon, F.; Chiron, H.; Saulnier, L.; Kansou, K. Rheology of Wheat Flour Dough at Mixing. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2022, 47, 100873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attenburrow, G.; Barnes, D.J.; Davies, A.P.; Ingman, S.J. Rheological Properties of Wheat Gluten. J. Cereal Sci. 1990, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berland, S.; Relkin, P.; Launay, B. Calorimetric and Rheological Properties of Wheat Flour Suspensions and Doughs: Effects of Wheat Types and Milling Procedure. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2003, 71, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, A.; Miura, M.; Ikeda, T.M.; Kaneko, S.; Kobayashi, R. Factors Affecting Rheological Properties of Barley Flour-Derived Batter and Dough Examined from Particle Properties. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 129, 107645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, I.; Souza, M.A.D.; Cardoso, A.A.; Sediyama, C.S.; Moreira, M.A. Correlation between High Molecular Weight Gluten Subunits Composition and Bread-Making Quality in Brazilian Wheat. Braz. J. Genet. 1997, 20, 667–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shewry, P.R.; Halford, N.G.; Belton, P.S.; Tatham, A.S. The Structure and Properties of Gluten: An Elastic Protein from Wheat Grain. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 2002, 357, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, M.; Maruyama-Funatsuki, W.; Ikeda, T.M.; Nishio, Z.; Nagasawa, K.; Tabiki, T. Dough Properties and Bread-Making Quality-Related Characteristics of Yumechikara near-Isogenic Wheat Lines Carrying Different Glu-B3 Alleles. Breed. Sci. 2015, 65, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ozturk, S.; Kahraman, K.; Tiftik, B.; Koksel, H. Predicting the Cookie Quality of Flours by Using Mixolab®. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2008, 227, 1549–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacko-Bartošová, M.; Konvalina, P.; Lacko-Bartošová, L.; Štěrba, Z. Quality Evaluation of Emmer Wheat Genotypes Based on Rheological and Mixolab Parameters. Czech J. Food Sci. 2019, 37, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragaee, S.; Abdel-Aal, E.-S.M. Pasting Properties of Starch and Protein in Selected Cereals and Quality of Their Food Products. Food Chem. 2006, 95, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Gujral, H.S. Mixolab Thermo-Mechanical Behaviour of Millet Flours and Their Cookie Doughs, Flour Functionality and Baking Characteristics. J. Cereal Sci. 2024, 116, 103866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.; Gujral, H.S.; Solah, V. Effect of Incorporating Finger Millet in Wheat Flour on Mixolab Behavior, Chapatti Quality and Starch Digestibility. Food Chem. 2017, 231, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfil, D.J.; Posner, E.S. Can Bread Wheat Quality Be Determined by Gluten Index? J. Cereal Sci. 2012, 56, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jukić, M.; Komlenić, D.; Mastanjević, K.; Mastanjević, K.; Lučan, M.; Popovici, C.; Nakov, G.; Lukinac, J. Influence of Damaged Starch on the Quality Parameters of Wheat Dough and Bread. Ukr. Food J. 2019, 8, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, S.; Lee, S.M.; Shim, J.-H.; Yoo, S.-H.; Lee, S. Effect of Dry- and Wet-Milled Rice Flours on the Quality Attributes of Gluten-Free Dough and Noodles. J. Food Eng. 2013, 116, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masbernat, L.; Berland, S.; Almeida, G.; Michon, C. Stabilizing Highly Hydrated Wheat Flour Doughs by Adding Water in Two Steps. J. Cereal Sci. 2021, 98, 103179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Gujral, H.S.; Katyal, M.; Sharma, B. Relationship of Mixolab Characteristics with Protein, Pasting, Dynamic and Empirical Rheological Characteristics of Flours from Indian Wheat Varieties with Diverse Grain Hardness. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 2679–2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papoušková, L.; Capouchová, I.; Kostelanská, M.; Škeříková, A.; Prokinová, E.; Hajšlová, J.; Salava, J.; Faměra, O. Changes in Baking Quality of Winter Wheat with Different Intensity of Fusarium Spp. Contamination Detected by Means of New Rheological System. Czech J. Food Sci. 2011, 29, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banu, I.; Stoenescu, G.; Ionescu, V.; Aprodu, I. Estimation of the Baking Quality of Wheat Flours Based on Rheological Parameters of the Mixolab Curve. Czech J. Food Sci. 2011, 29, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawęda, D.; Haliniarz, M. Grain Yield and Quality of Winter Wheat Depending on Previous Crop and Tillage System. Agriculture 2021, 11, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, N.; Du, C.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, Z. Did Wheat Breeding Simultaneously Improve Grain Yield and Quality of Wheat Cultivars Releasing over the Past 20 Years in China? Agronomy 2022, 12, 2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppensteiner, L.J.; Kaul, H.-P.; Piepho, H.-P.; Barta, N.; Euteneuer, P.; Bernas, J.; Klimek-Kopyra, A.; Gronauer, A.; Neugschwandtner, R.W. Yield and Yield Components of Facultative Wheat Are Affected by Sowing Time, Nitrogen Fertilization and Environment. Eur. J. Agron. 2022, 140, 126591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slafer, G.A.; Kantolic, A.G.; Appendino, M.L.; Tranquilli, G.; Miralles, D.J.; Savin, R. Genetic and Environmental Effects on Crop Development Determining Adaptation and Yield. In Crop Physiology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 285–319. ISBN 978-0-12-417104-6. [Google Scholar]

- Studnicki, M.; Wijata, M.; Sobczyński, G.; Samborski, S.; Gozdowski, D.; Rozbicki, J. Effect of Genotype, Environment and Crop Management on Yield and Quality Traits in Spring Wheat. J. Cereal Sci. 2016, 72, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Li, L.; Peng, P.; Zhang, K.; Hu, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhao, G. Wheat Cultivar Mixtures Increase Grain Yield under Varied Climate Conditions. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2023, 69, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rwubatse, B.; Okoth, M.W.; Andago, A.A.; Ngala, S.; Kimonyo, A.; Bitwayiki, C. Effect of Selected Rwandan Wheat Varieties on the Physicochemical Characteristics of Whole Wheat Flour. Acta Agric. Slov. 2021, 117, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Zhang, Z.; Yin, Y.; Yan, S.; Ren, Y.; Sang, W.; Xu, H.; Han, X.; Cui, F.; Nie, Y.; et al. Quality Traits Analysis of 153 Wheat Lines Derived from CIMMYT and China. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1198835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, C.; Ammar, K.; Govindan, V.; Singh, R. Genetic Improvement of Wheat Grain Quality at CIMMYT. Front. Agr. Sci. Eng. 2019, 6, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatrice, N.T.; Pascal, P.O.O.; Daniel, O. Maurice Wheat Stem Rust Disease Incidence Severity Associated with Farming Practices in the Central Rift Valley of Kenya. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2016, 11, 2640–2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harisha, R.; Ahlawat, A.K.; Balakrishna, A.P.; Bhavya, B.; Singh, S.K.; Singhal, S.; Narwal, S.; Jaiswal, J.P.; Singh, J.B.; Kumar, R.R.; et al. Unraveling the Effects of Genotype, Environment and Their Interaction on Quality Attributes of Diverse Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Genotypes. Indian J. Genet. Plant Breed. 2024, 84, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedő, Z.; Láng, L.; Rakszegi, M. Breeding for Grain-Quality Traits. In Cereal Grains; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 425–452. ISBN 978-0-08-100719-8. [Google Scholar]

- Tadesse, W.; Bishaw, Z.; Assefa, S. Wheat Production and Breeding in Sub-Saharan Africa: Challenges and Opportunities in the Face of Climate Change. Int. J. Clim. Change Strateg. Manag. 2019, 11, 696–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, C.; Ibba, M.I. Wheat Quality Testing in a Breeding Program. In ICC Handbook of 21st Century Cereal Science and Technology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 207–213. ISBN 978-0-323-95295-8. [Google Scholar]

| Variety | TKW (g) | Hectoliter Weight (kg hL−1) | Protein Content (%) | Gluten Index (%) | Wet Gluten (%) | Falling Number (s) | ZSV (mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nyaruka | 33.50 ± 0.10 cd | 76.70 ± 0.34 de | 9.65 ± 0.02 de | 51.19 ± 19.22 b–d | 20.27 ± 0.91 d | 447.0 ± 4.00 cd | 24.7 ± 0.57 e |

| Gihundo | 36.49 ± 0.42 ab | 80.87 ± 0.32 a | 9.49 ± 0.17 e | 40.15 ± 2.96 cd | 18.64 ± 0.80 e | 506.0 ± 5.00 a | 15.7 ± 1.15 f |

| Reberaho | 29.91 ± 0.92 e | 79.30 ± 0.10 a–c | 10.55 ± 0.26 ab | 92.59 ± 0.07 a | 20.91 ± 0.03 cd | 458.0 ± 6.00 c | 31.0 ± 1.00 d |

| Majyambere | 33.36 ± 0.97 cd | 77.63 ± 0.41 b–e | 9.96 ± 0.09 c–e | 92.66 ± 0.55 a | 19.77 ± 0.13 de | 454.0 ± 1.00 c | 32.0 ± 1.00 d |

| Kibatsi | 35.04 ± 0.18 bc | 79.20 ± 0.20 a–c | 10.14 ± 0.15 b–d | 43.40 ± 4.03 cd | 21.59 ± 0.06 bc | 485.0 ± 13.00 b | 24.7 ± 0.57 e |

| Cyumba | 32.18 ± 0.31 d | 76.83 ± 0.32 c–e | 10.72 ± 0.09 a | 73.62 ± 8.40 ab | 21.60 ± 0.20 bc | 426.0 ± 1.00 ef | 36.3 ± 0.57 c |

| Nyangufi | 38.20 ± 0.14 a | 78.13 ± 2.55 b–d | 10.45 ± 0.07 a–c | 95.22 ± 0.14 a | 21.97 ± 0.02 a–c | 457.0 ± 1.00 c | 46.0 ± 1.00 a |

| Rengerabana | 32.98 ± 0.06 d | 75.60 ± 0.26 e | 10.44 ± 0.07 a–c | 30.88 ± 5.61 d | 22.82 ± 0.07 a | 431.3 ± 8.50 de | 30.3 ± 0.57 d |

| Keza | 32.68 ± 0.63 d | 79.40 ± 0.43 ab | 10.36 ± 0.42 a–c | 95.46 ± 0.05 a | 20.18 ± 0.22 d | 409.3 ± 10.50 f | 41.3 ± 0.57 b |

| Mizero | 33.43 ± 1.06 cd | 79.03 ± 0.15 a–d | 10.11 ± 0.08 b–d | 60.44 ± 11.45 bc | 22.52 ± 0.00 ab | 464.3 ± 0.57 c | 30.3 ± 0.57 d |

| p-Value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Variety | WA (%) | TC2 (Nm) | TC3 (Nm) | TC4 (Nm) | TC5 (Nm) | Amp. (Nm) | Stab. (min) | α | β | γ | TimeC1 (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nyaruka | 60.0 d | 0.48 a | 1.82 ab | 1.27 d–f | 2.53 fg | 0.08 ab | 6.3 e | −0.057 a | 0.55 b | −0.01 a | 2.74 d |

| Gihundo | 60.8 cd | 0.49 a | 1.75 b–d | 1.18 e–g | 2.83 bc | 0.07 a–c | 5.6 f | −0.070 a–c | 0.52 b | −0.30 d | 2.20 e |

| Reberaho | 64.0 a | 0.53 a | 1.76 a–c | 1.56 ab | 2.49 g | 0.07 bc | 9.3 b | −0.09 d | 0.43 cd | −0.07 a–c | 3.65 b |

| Majyabere | 61.5 bc | 0.51 a | 1.68 d | 1.164 fg | 2.59 ef | 0.09 a | 8.6 c | −0.082 cd | 0.41 d | −0.13 c | 3.25 c |

| Kibatsi | 62.5 b | 0.50 a | 1.71 cd | 1.16 fg | 2.90 b | 0.09 a | 5.4 f | −0.066 ab | 0.53 b | −0.30 d | 2.08 e |

| Cyumba | 64.0 a | 0.53 a | 1.72 cd | 1.45 bc | 2.31 h | 0.07 bc | 8.4 c | −0.084 cd | 0.50 bc | −0.06 ab | 3.18 c |

| Nyangufi | 58.5 e | 0.55 a | 1.72 cd | 1.38 cd | 3.30 a | 0.09 a | 9.5 b | −0.064 ab | 0.63 a | −0.006 a | 3.85 b |

| Rengerabana | 60.0 d | 0.45 a | 1.78 a–c | 1.60 a | 2.64 e | 0.09 a | 6.4 e | −0.07 a–c | 0.56 ab | −0.07 a–c | 1.58 f |

| Keza | 62.5 b | 0.55 a | 1.77 a–c | 1.31 de | 2.82 cd | 0.09 a | 9.9 a | −0.084 cd | 0.37 d | −0.11 bc | 4.77 a |

| Mizero | 61.5 bc | 0.51 a | 1.83 a | 1.10 g | 2.75 d | 0.06 c | 8.0 d | −0.076 b–d | 0.56 ab | −0.38 e | 2.90 d |

| p-Value | <0.001 | ns | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Murindangabo, Y.T.; Hoang, T.N.; Habarurema, I.; Konvalina, P.; Niyibituronsa, M.; Byukusenge, P.; Mbasabire, P.; Uwihanganye, J.; Bwimba, R.; Ntezimana, M.G.; et al. Linking Yield, Baking Quality, and Rheological Properties to Guide Sustainable Improvement of Rwandan Wheat Varieties. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2160. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15202160

Murindangabo YT, Hoang TN, Habarurema I, Konvalina P, Niyibituronsa M, Byukusenge P, Mbasabire P, Uwihanganye J, Bwimba R, Ntezimana MG, et al. Linking Yield, Baking Quality, and Rheological Properties to Guide Sustainable Improvement of Rwandan Wheat Varieties. Agriculture. 2025; 15(20):2160. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15202160

Chicago/Turabian StyleMurindangabo, Yves Theoneste, Trong Nghia Hoang, Innocent Habarurema, Petr Konvalina, Marguerite Niyibituronsa, Protegene Byukusenge, Protogene Mbasabire, Josine Uwihanganye, Roger Bwimba, Marie Grace Ntezimana, and et al. 2025. "Linking Yield, Baking Quality, and Rheological Properties to Guide Sustainable Improvement of Rwandan Wheat Varieties" Agriculture 15, no. 20: 2160. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15202160

APA StyleMurindangabo, Y. T., Hoang, T. N., Habarurema, I., Konvalina, P., Niyibituronsa, M., Byukusenge, P., Mbasabire, P., Uwihanganye, J., Bwimba, R., Ntezimana, M. G., & Tran, D. K. (2025). Linking Yield, Baking Quality, and Rheological Properties to Guide Sustainable Improvement of Rwandan Wheat Varieties. Agriculture, 15(20), 2160. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15202160