Fertility-Based Nitrogen Management Strategies Combined with Straw Return Enhance Rice Yield and Soil Quality in Albic Soils

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Sampling and Determinations

2.3.1. Soil Sample Collection and Chemical Analysis

2.3.2. In-Situ Soil Sampling and Physical Property Analysis

2.3.3. Rice Yield

2.3.4. Partial Factor Productivity of Nitrogen (PFPN)

2.3.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

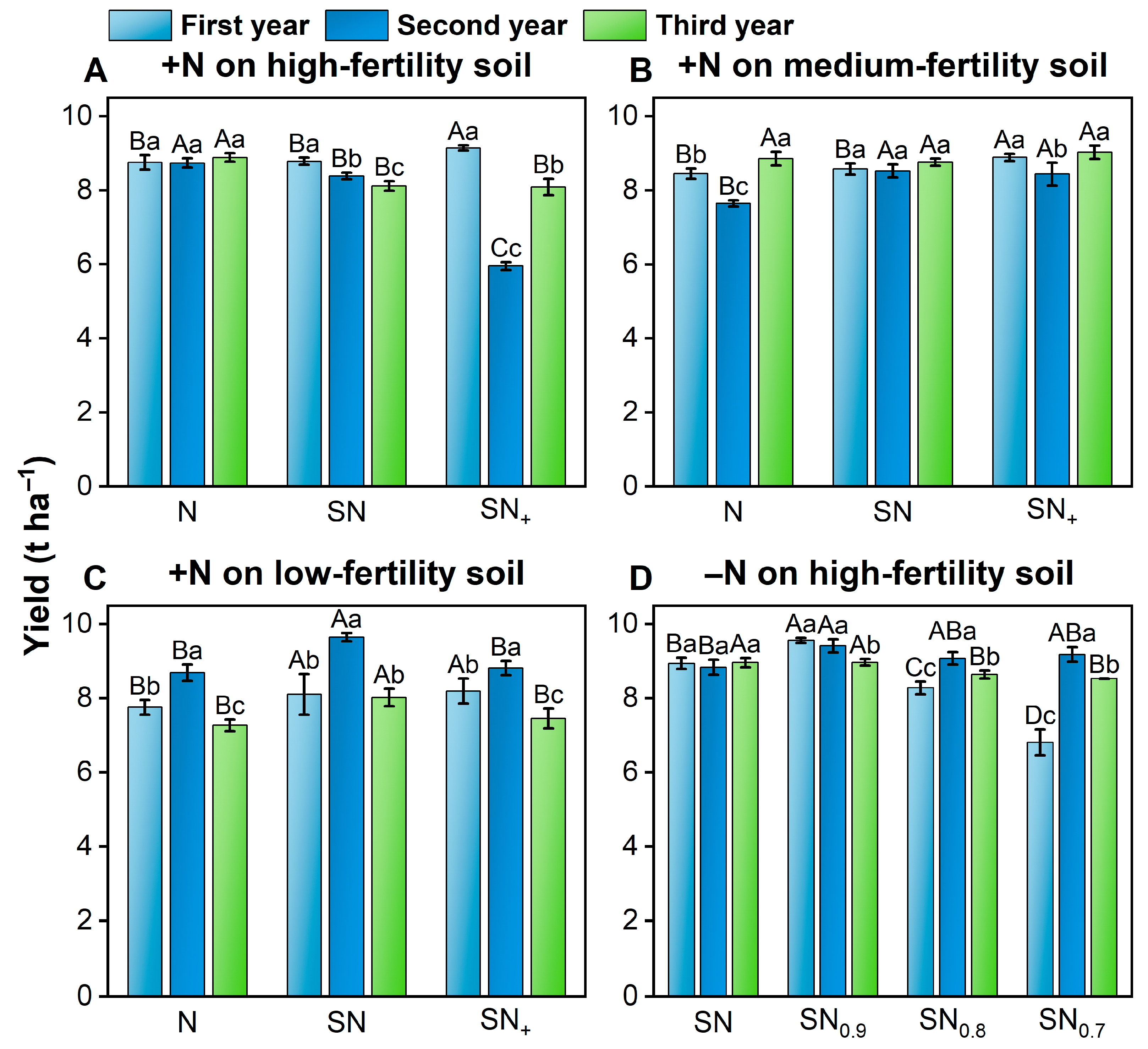

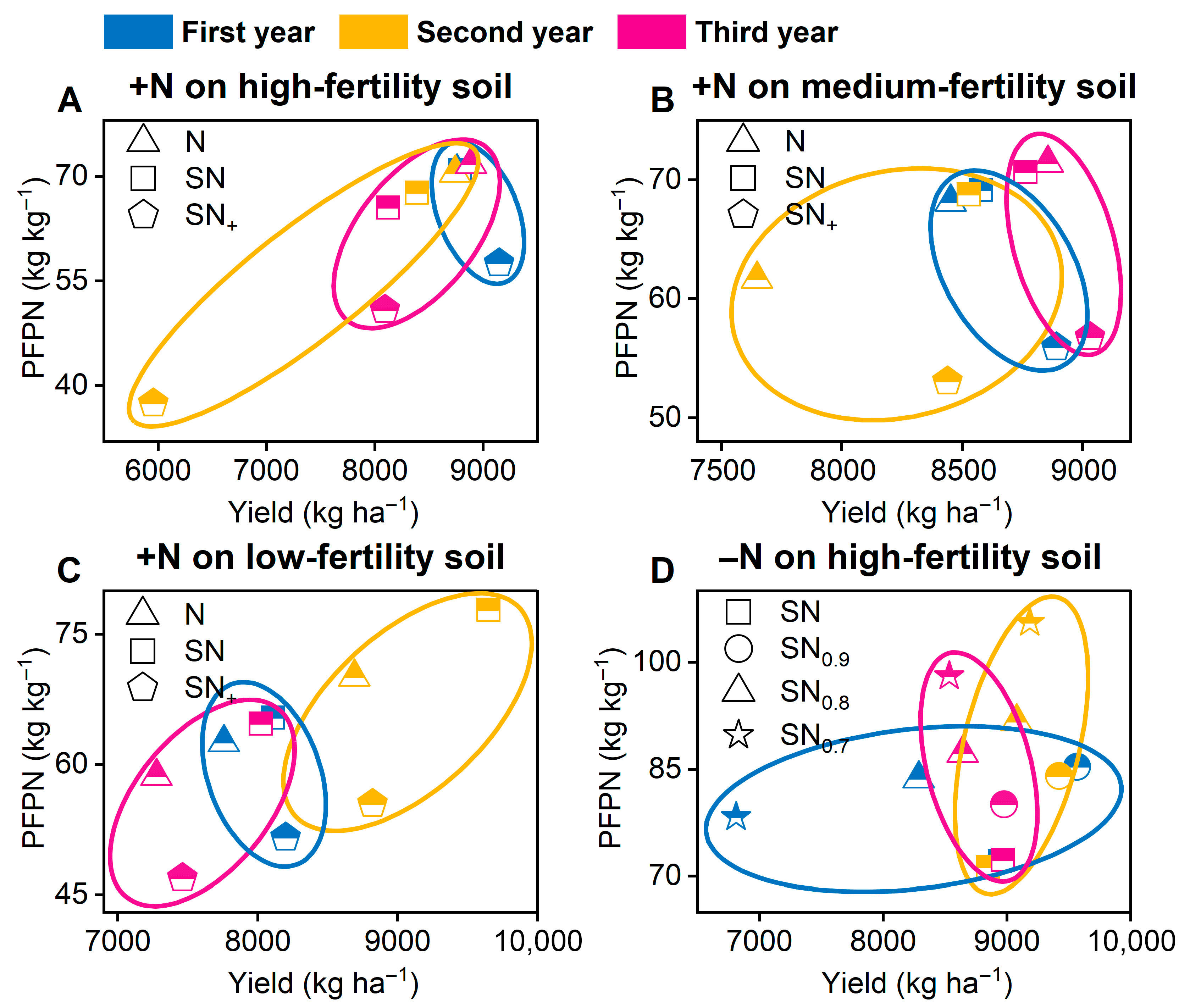

3.1. Rice Yield and PFPN

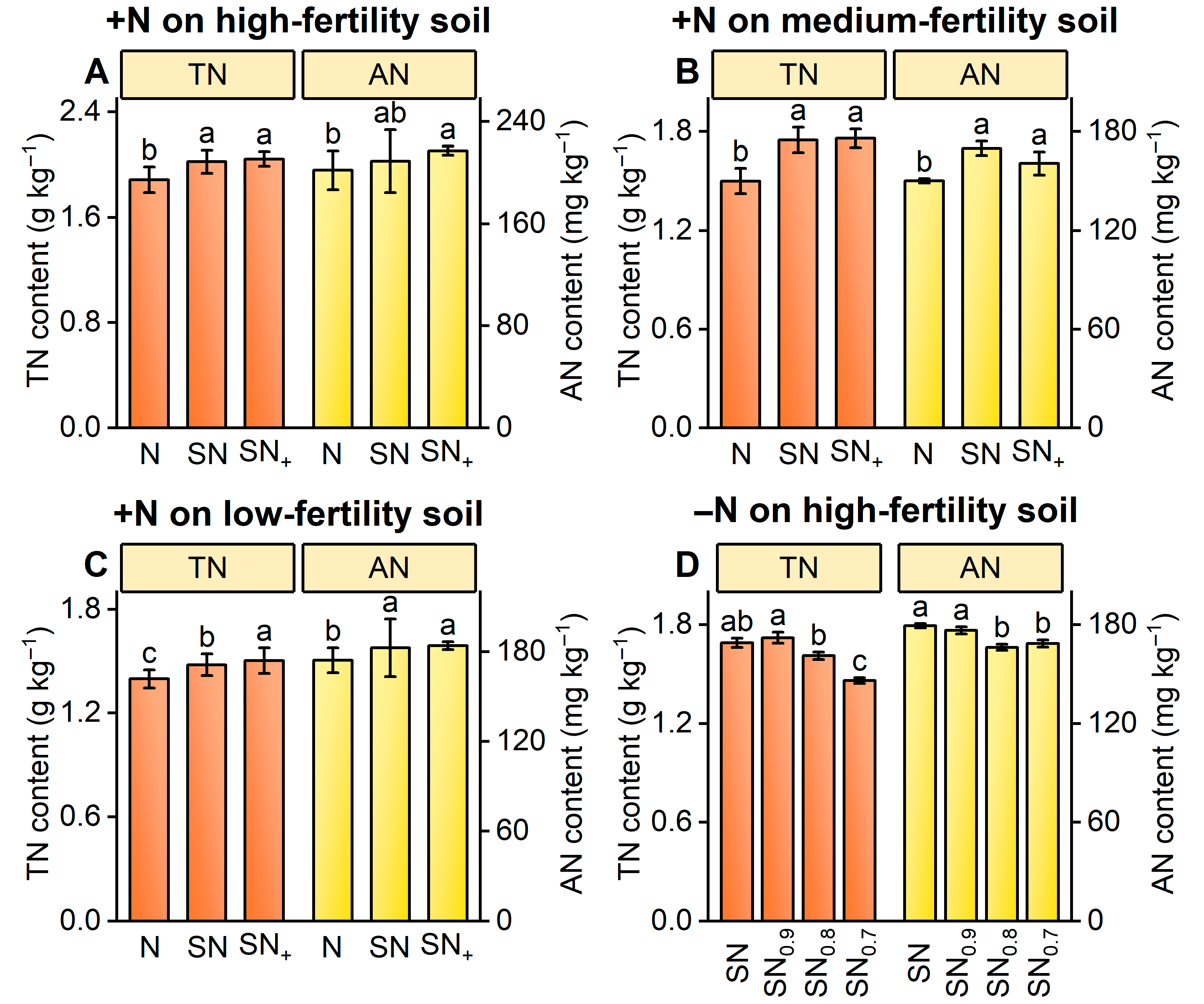

3.2. Soil Nutrient Contents

3.2.1. Soil Nitrogen

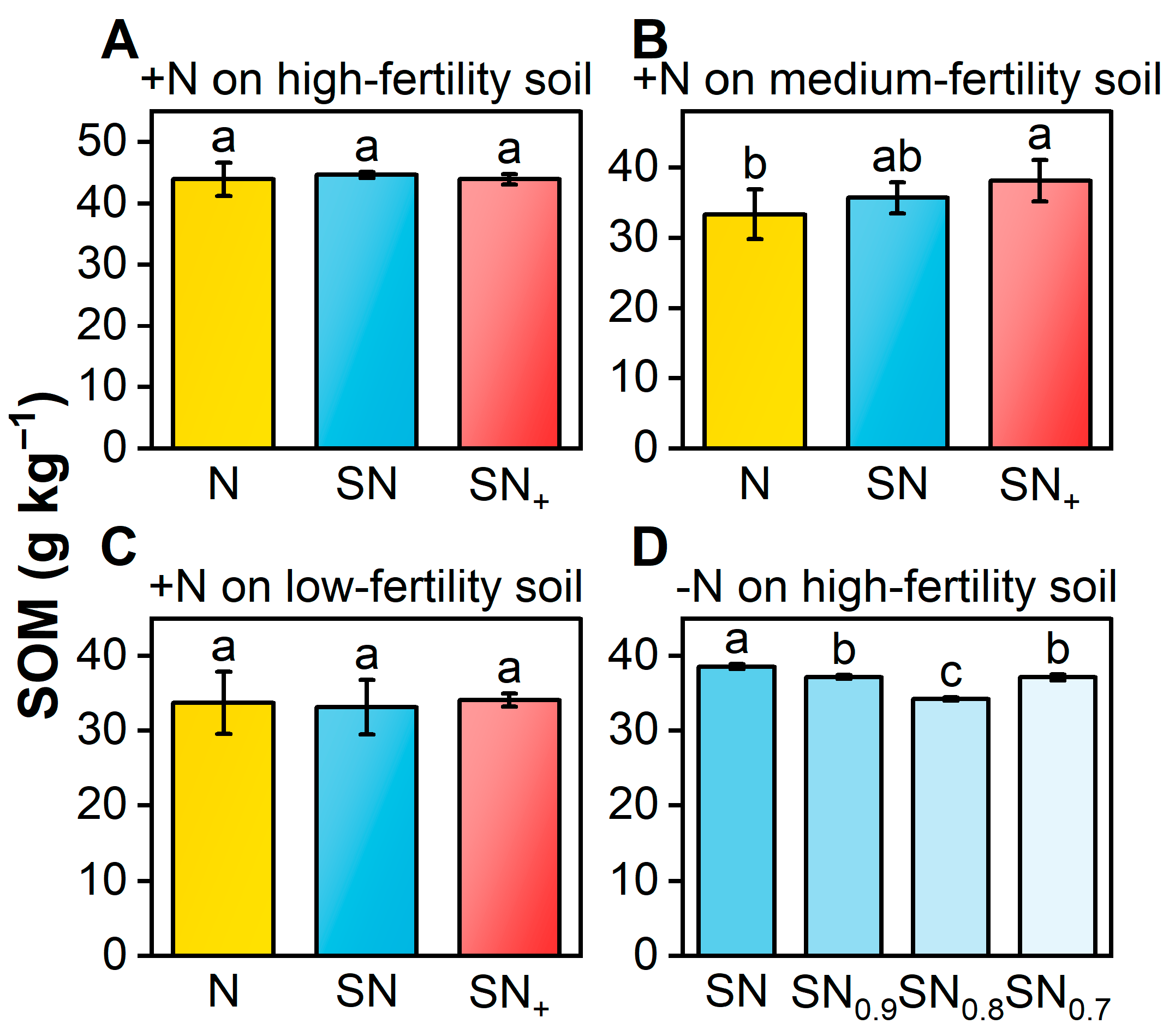

3.2.2. Soil Organic Matter (SOM)

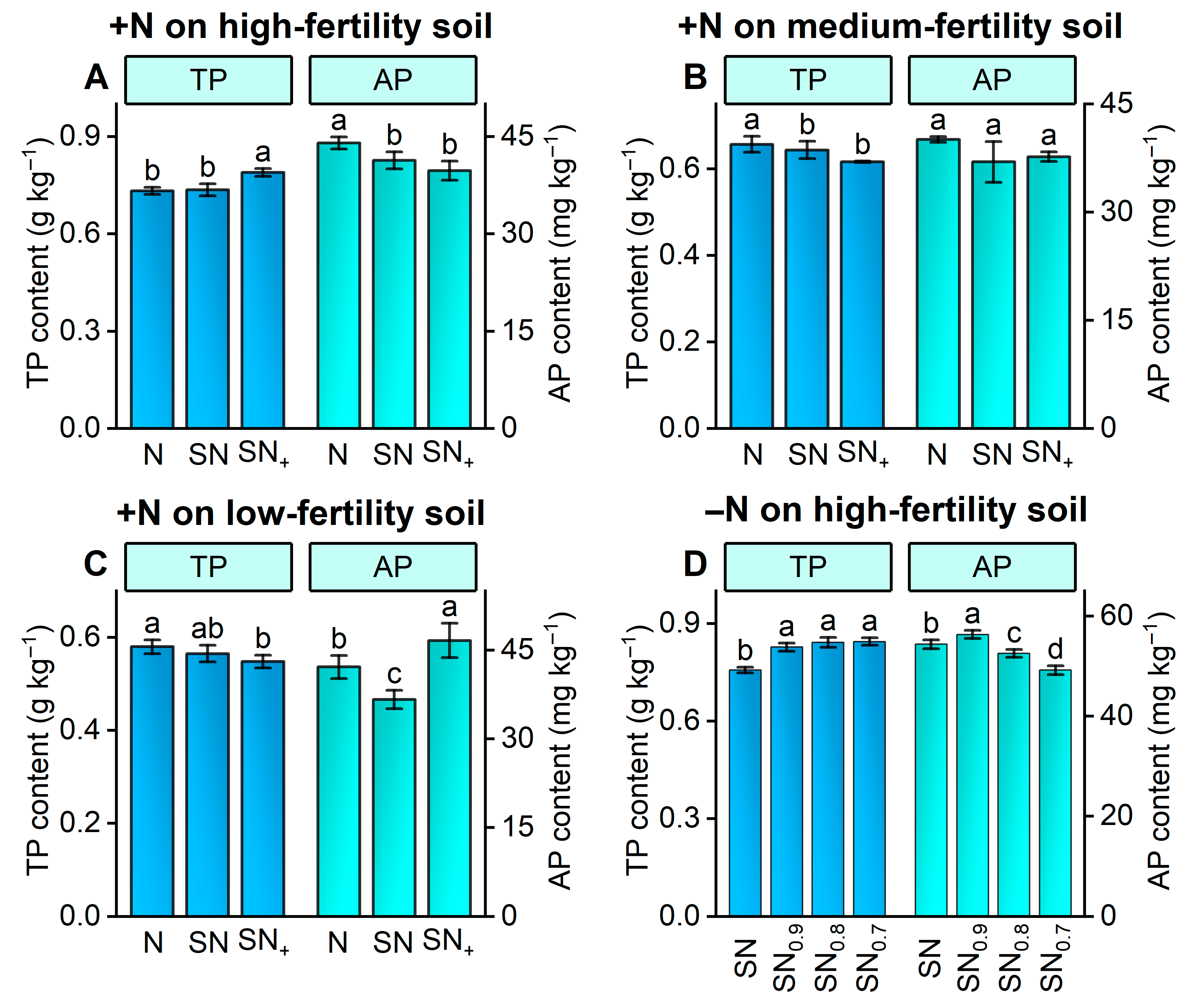

3.2.3. Soil Phosphorus

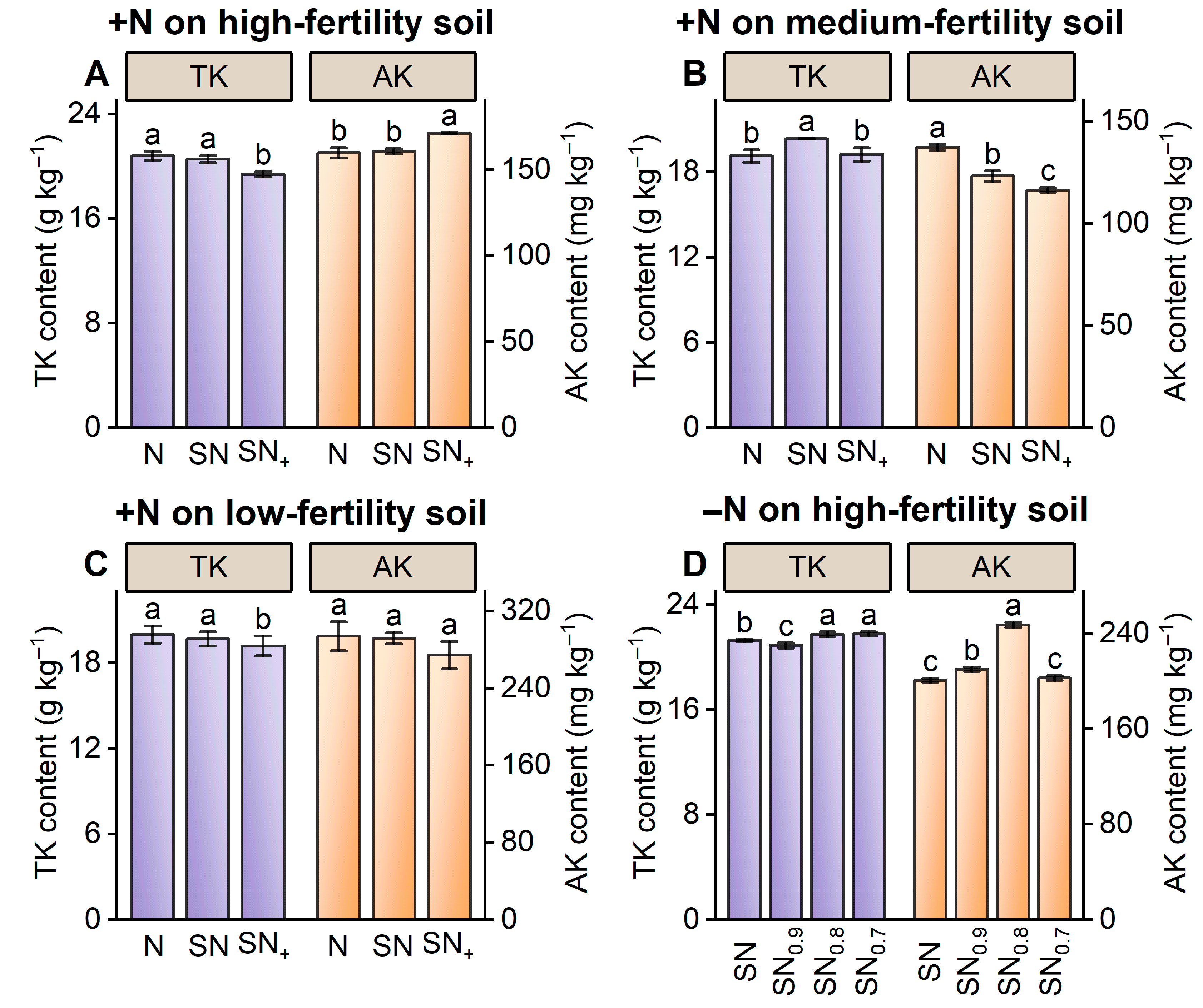

3.2.4. Soil Potassium

3.3. Soil Physical Properties

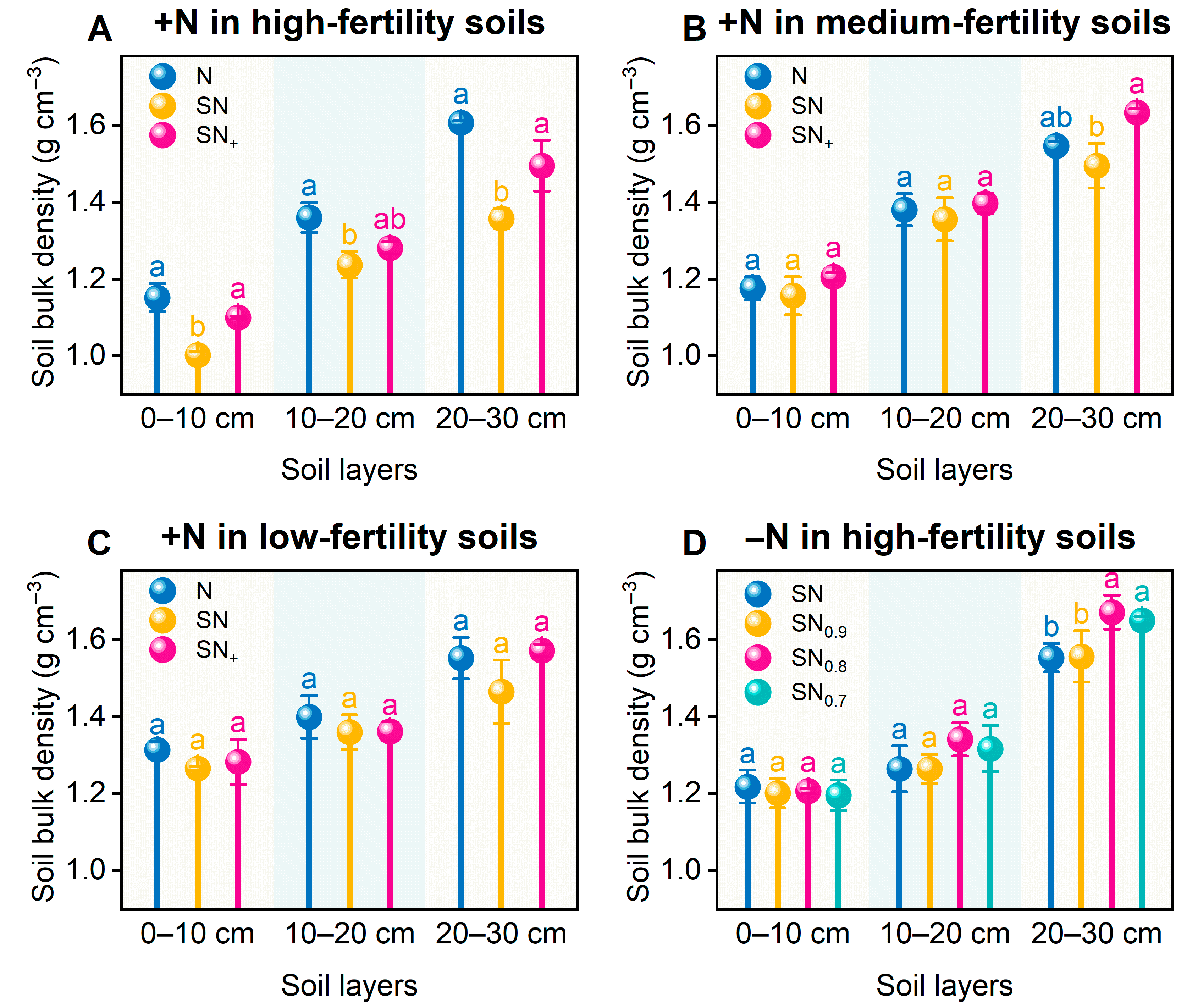

3.3.1. Soil Bulk Density

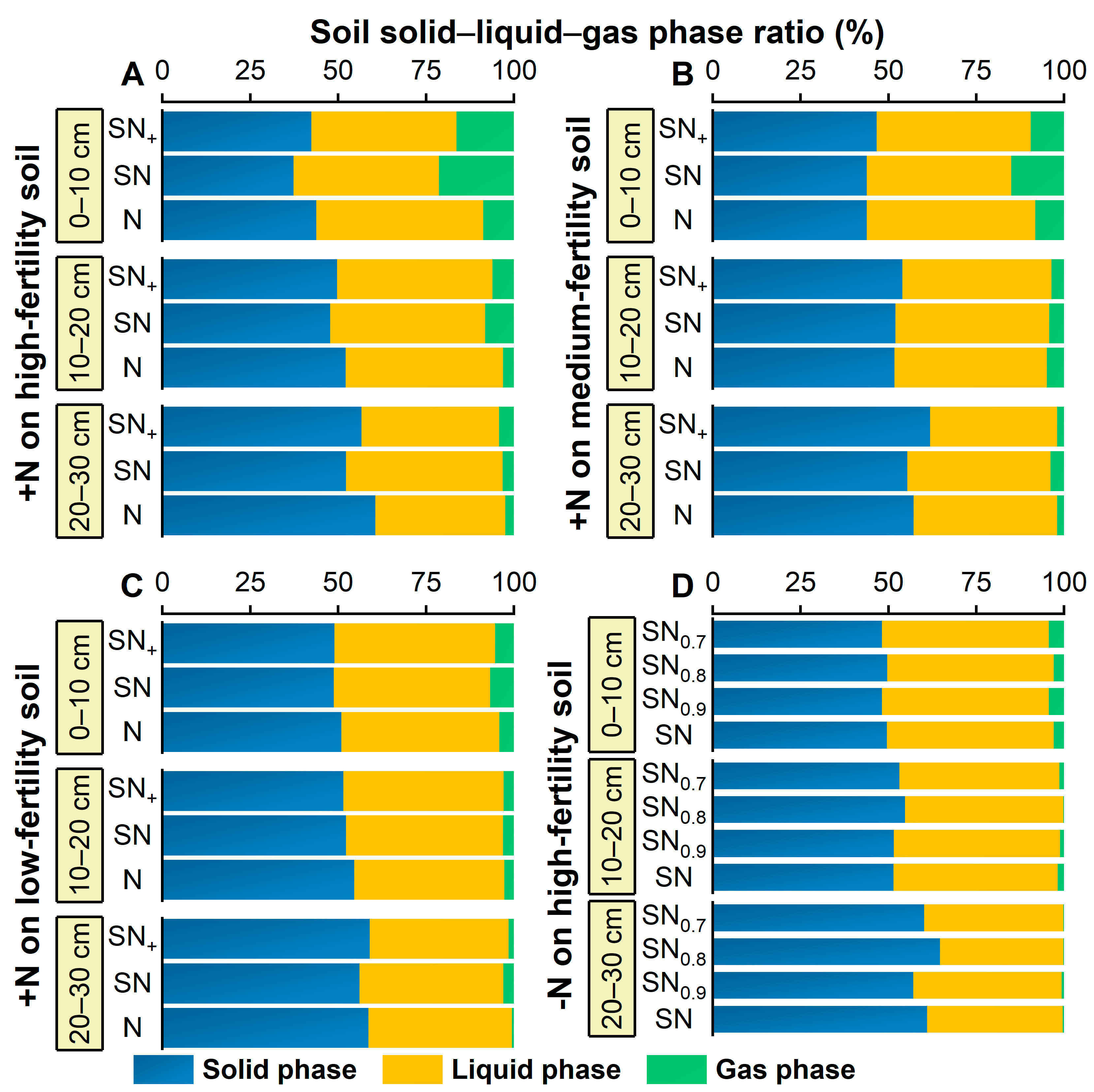

3.3.2. Three Phases of Soil

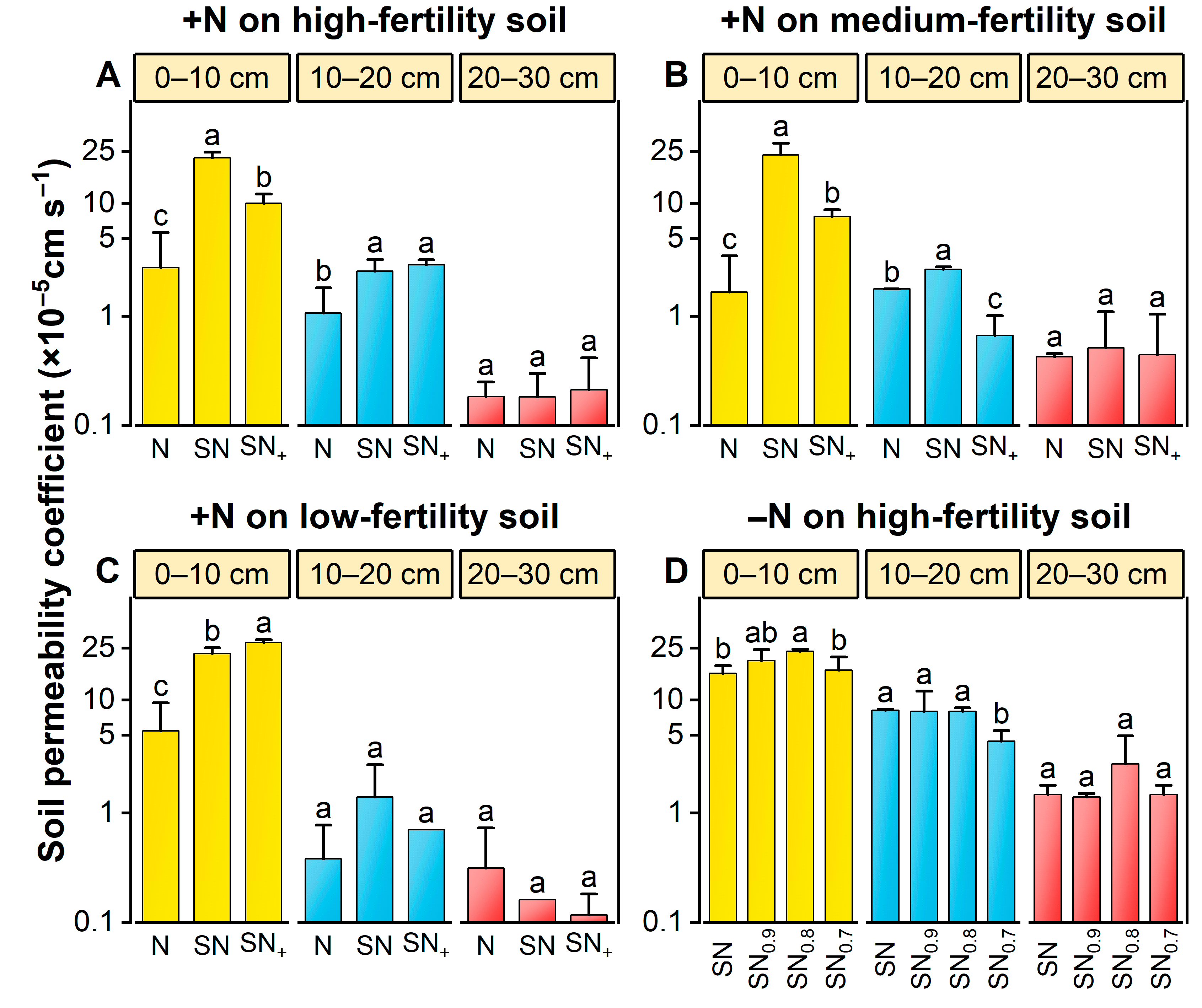

3.3.3. Soil Permeability

3.3.4. Soil Aeration

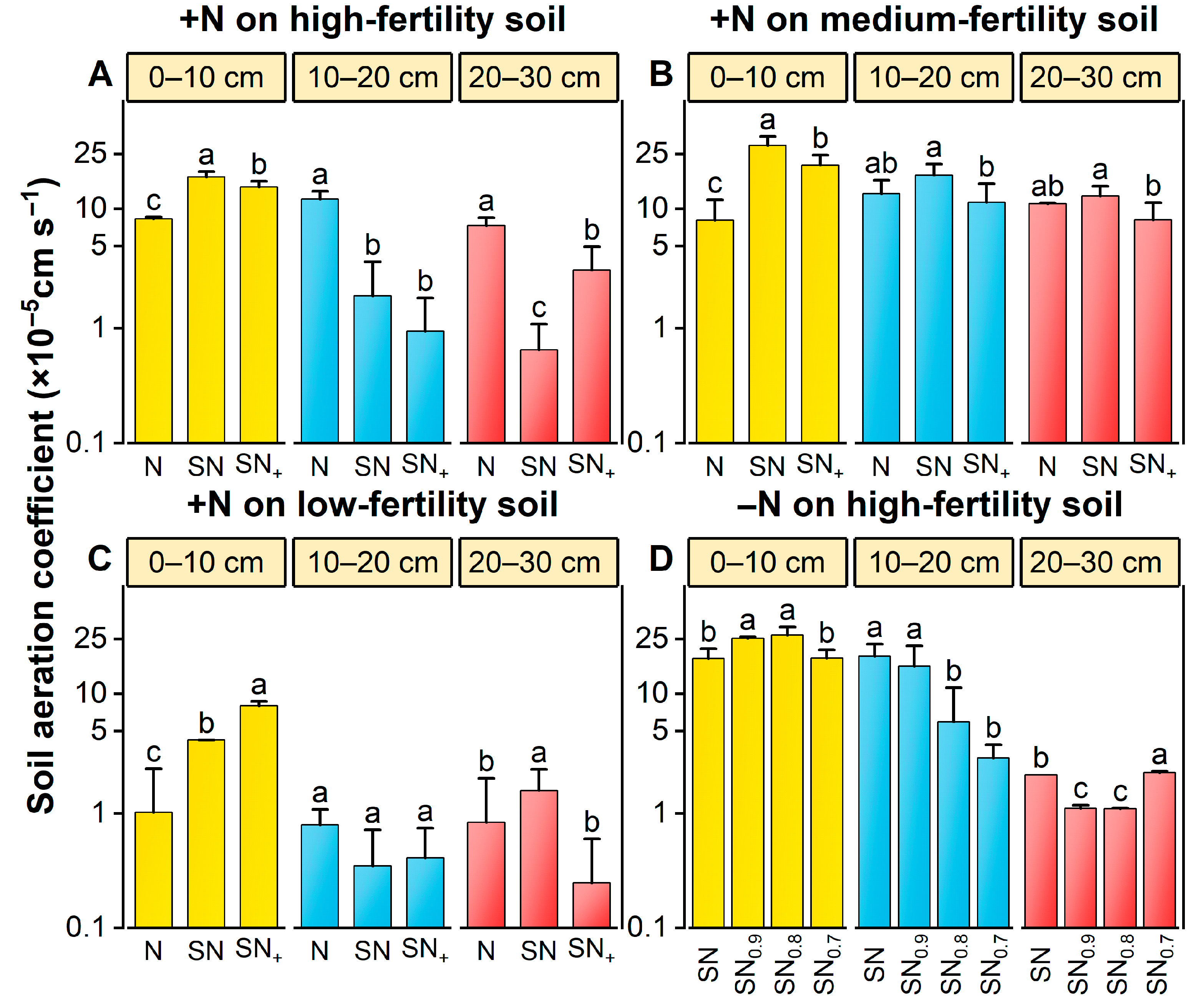

3.3.5. Soil Saturated Water Content (SWC) and Field Water-Holding Capacity (WHC)

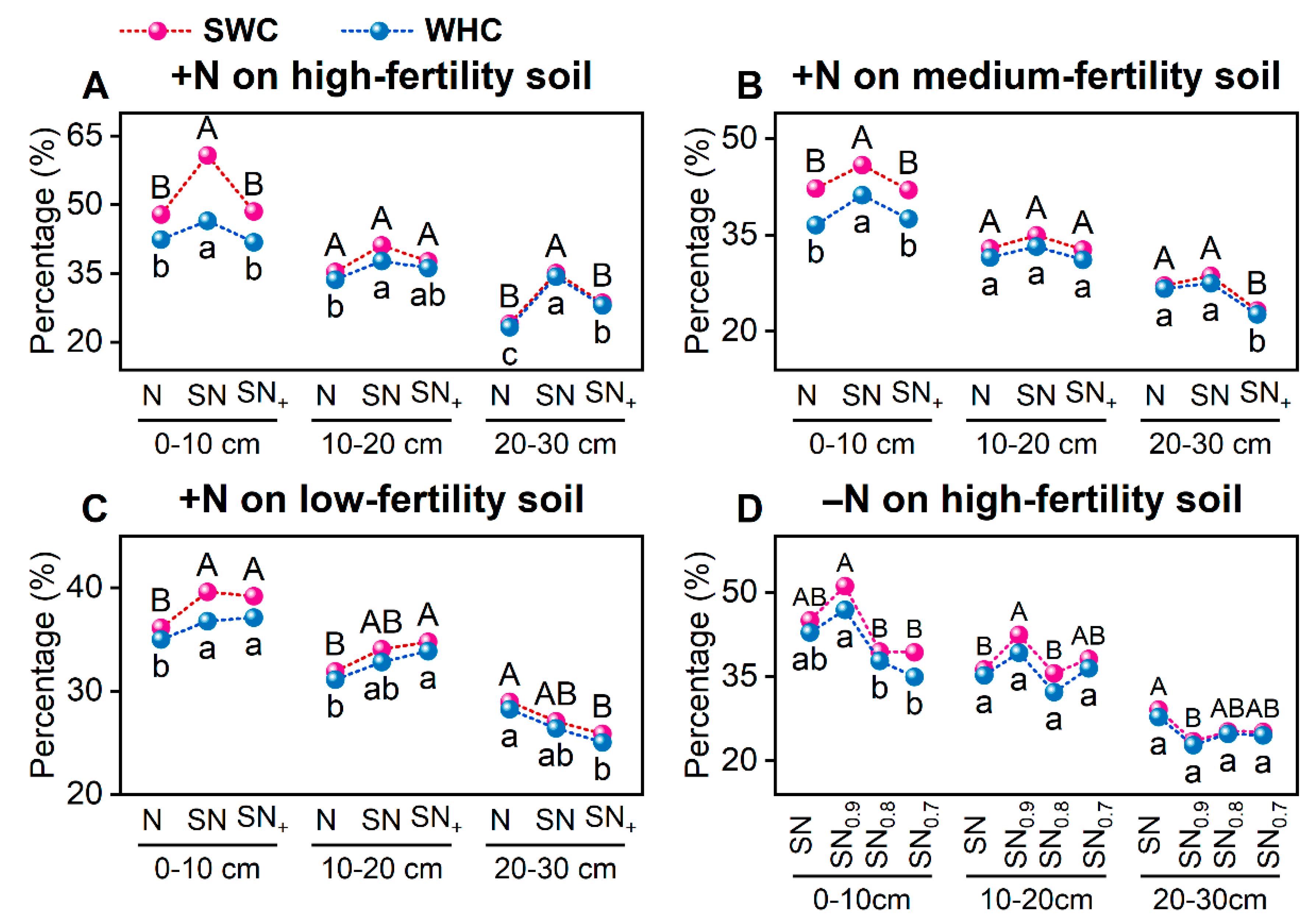

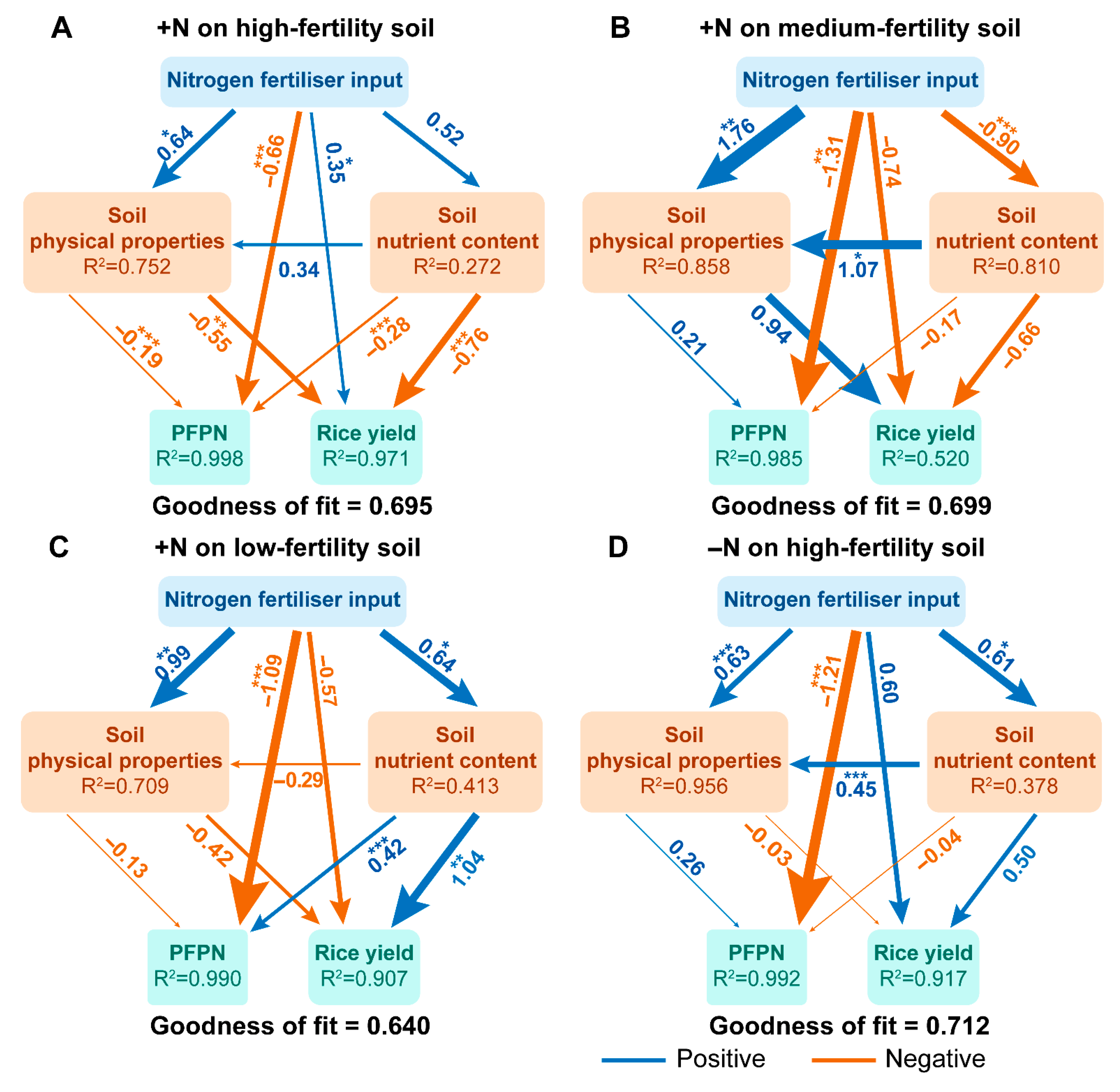

3.4. Correlation Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Erisman, J.W.; Sutton, M.A.; Galloway, J.; Klimont, Z.; Winiwarter, W. How a century of ammonia synthesis changed the world. Nat. Geosci. 2008, 1, 636–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfray, H.C.J.; Beddington, J.R.; Crute, I.R.; Haddad, L.; Lawrence, D.; Muir, J.F.; Pretty, J.; Robinson, S.; Thomas, S.M.; Toulmin, C. Food Security: The Challenge of Feeding 9 Billion People. Science 2010, 327, 812–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Keitel, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wangeci, A.N.; Dijkstra, F.A. Global meta-analysis of nitrogen fertilizer use efficiency in rice, wheat and maize. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2022, 338, 108089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.H.; Liu, X.J.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, J.L.; Han, W.X.; Zhang, W.F.; Christie, P.; Goulding, K.W.T.; Vitousek, P.M.; Zhang, F.S. Significant Acidification in Major Chinese Croplands. Science 2010, 327, 1008–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adalibieke, W.; Cui, X.; Cai, H.; You, L.; Zhou, F. Global crop-specific nitrogen fertilization dataset in 1961–2020. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xu, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, D.; Li, L.; Li, W.; Sheng, L. Effects of long-term application of organic fertilizer on improving organic matter content and retarding acidity in red soil from China. Soil Tillage Res. 2019, 195, 104382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sun, J.; Zhao, T.; Wang, L.; Zhao, C.; Fu, J.; Li, D.; Yu, H. Effects of Fe/Mg-modified lignocellulosic biochar on in vitro ruminal microorganism fermentation of corn stover. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 421, 132172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Tremblay, J.; Bainard, L.D.; Cade-Menun, B.; Hamel, C. Long-term effects of nitrogen and phosphorus fertilization on soil microbial community structure and function under continuous wheat production. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 22, 1066–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckley, C.; Carney, P. The potential to reduce the risk of diffuse pollution from agriculture while improving economic performance at farm level. Environ. Sci. Policy 2013, 25, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Davidson, E.A.; Mauzerall, D.L.; Searchinger, T.D.; Dumas, P.; Shen, Y. Managing nitrogen for sustainable development. Nature 2015, 528, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z. Forest Soil Management in Cold Regions; China Forestry Publishing House: Beijing, China, 1992; pp. 45–68. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Soil Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Soils of China; Science Press: Beijing, China, 1978; pp. 128–134. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Z.; Zhang, H.; Chen, X.; Zhang, C.; Ma, W.; Huang, C.; Zhang, W.; Mi, G.; Miao, Y.; Li, X.; et al. Pursuing sustainable productivity with millions of smallholder farmers. Nature 2018, 555, 363–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, G.; Wang, D.; Liu, Q.; Xu, M. Investigation into runoff nitrogen loss variations due to different crop residue retention modes and nitrogen fertilizer rates in rice-wheat cropping systems. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 247, 106729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Chen, X.; Vitousek, P. An experiment for the world. Nature 2013, 497, 33–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-J.; Wei, R.; Tang, H.; Zhao, J.; Lin, C. An integrated scheduling framework for synchronizing harvesting and straw returning. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 189, 106360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaliwal, S.S.; Naresh, R.K.; Gupta, R.K.; Panwar, A.S.; Mahajan, N.C.; Singh, R.; Mandal, A. Effect of tillage and straw return on carbon footprints, soil organic carbon fractions and soil microbial community in different textured soils under rice-wheat rotation: A review. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio-Technol. 2020, 19, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Cheng, M.; Yang, L.; Gu, X.; Jin, J.; Fu, M. Regulation of straw decomposition and its effect on soil function by the amount of returned straw in a cool zone rice crop system. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 15673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Song, J.; Xu, W.; Gao, G.; Bai, J.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, Q.; Hao, J.; Yang, G.; Ren, G.; et al. Straw return with fertilizer improves soil CO2 emissions by mitigating microbial nitrogen limitation during the winter wheat season. Catena 2024, 241, 108050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Jiao, Y.; Fan, L.; Jiang, Y.; Qu, C.; Filimonenko, E.; Jiang, Y.; Tian, X.; et al. Nitrogen fertilizer builds soil organic carbon under straw return mainly via microbial necromass formation. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2024, 188, 109223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-f.; Zhong, F.-f. Nitrogen release and re-adsorption dynamics on crop straw residue during straw decomposition in an Alfisol. J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Liu, D.; Liao, X.; Miao, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Yuan, J.; Chen, Z.; Ding, W. Field-aged biochar enhances soil organic carbon by increasing recalcitrant organic carbon fractions and making microbial communities more conducive to carbon sequestration. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2022, 340, 108177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Guan, X.; Liang, X.; Wang, B.; Chen, X.; He, X.; Xie, J.; Deng, G.; Chen, J.; Li, X.; et al. Optimizing the Nitrogen Fertilizer Management to Maximize the Benefit of Straw Returning on Early Rice Yield by Modulating Soil N Availability. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.; Liu, M.; Qi, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, B.; Yin, Z.; Xu, J.; Sun, J. Straw returning and reducing nitrogen application rates maintain maize yields and reduce gaseous nitrogen emissions from black soil maize fields. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 203, 105637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Li, Y.; Wei, J.L.; Li, Z.S.; Zhou, X.L.; Zheng, F.L.; Wu, X.B.; Wang, L.; Liu, Z.H.; Tan, D.S. Effects of Long-term Straw Returning on Fungal Community, Enzyme Activity and Wheat Yield in Fluvo-aquic Soil. Huan Jing Ke Xue 2022, 43, 4755–4764. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Qin, M.; Zhan, M.; Liu, T.; Yuan, J. Straw return-enhanced soil carbon and nitrogen fractions and nitrogen use efficiency in a maize–rice rotation system. Exp. Agric. 2024, 60, e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Wu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Liu, J.; Lin, L.; Xia, F.; Su, X.; Sun, Q.; Meng, J. Differential effects of biochar and straw incorporation on soil organic carbon: A case study on paddy cultivation in Northeast China. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 390, 126284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, G.; Wang, C. How does straw-incorporation rate reduce runoff and erosion on sloping cropland of black soil region? Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 357, 108676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Luo, G.; Zhu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Liao, C. Straw Returning Amount and Duration Influence Paddy Soil Organic Carbon Sequestration by Regulating Plant- and Microbe-Derived Carbon Accumulation. Land Degrad. Dev. 2025, 36, 3729–3741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, J.; Zhou, J.; Wu, G.; Zhao, D.-Q.; Wang, Z.-T.; Wen, Y.; Zhou, S.-L. Deep-injected straw incorporation enhances subsoil quality and wheat productivity. Plant Soil 2024, 499, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerasimova, M.I. Chinese soil taxonomy: Between the American and the international classification systems. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2010, 43, 945–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, H.; Vasava, H.B.; Chen, S.; Saurette, D.; Beri, A.; Gillespie, A.; Biswas, A. Evaluating the Soil Quality Index Using Three Methods to Assess Soil Fertility. Sensors 2024, 24, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO. Soil Quality—Pretreatment of Samples for Physico-Chemical Analysis; International Organization for Standardization: London, UK, 2006; p. 11464. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, S. Chemical Analysis for Agricultural Soil. In Chapter Three: Determination of Soil Organic Matter; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2000; pp. 68–70. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, R. Soil agro-chemical analyses. In Chapter 13: Soil Nitrogen Analysis; Agricultural Technical Press of China: Beijing, China, 2000; pp. 136–140. [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari, S.; Timms, W.; Mahmud, M.A.P. Optimising water holding capacity and hydrophobicity of biochar for soil amendment—A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 851, 158043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Meng, F.; Zhang, X.; Gao, Q.; Yan, L. Optimum management strategy for improving maize water productivity and partial factor productivity for nitrogen in China: A meta-analysis. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 303, 109043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St. Montgomery, D.C. Design and Analysis of Experiments, 9th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 33–65. [Google Scholar]

- Berhane, M.; Xu, M.; Liang, Z.; Shi, J.; Wei, G.; Tian, X. Effects of long-term straw return on soil organic carbon storage and sequestration rate in North China upland crops: A meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 2686–2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, U.E.; Toluwase, A.O.; Kehinde, E.O.; Omasan, E.E.; Tolulope, A.Y.; George, O.O.; Zhao, C.; Hongyan, W. Effect of biochar on soil structure and storage of soil organic carbon and nitrogen in the aggregate fractions of an Albic soil. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2020, 66, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Fan, L.; Zou, Y. Contrasting responses of grain yield to reducing nitrogen application rate in double- and single-season rice. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.-P.; Cui, Z.-L.; Vitousek, P.M.; Cassman, K.G.; Matson, P.A.; Bai, J.-S.; Meng, Q.-F.; Hou, P.; Yue, S.-C.; Römheld, V.; et al. Integrated soil–crop system management for food security. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 6399–6404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninkuu, V.; Liu, Z.; Qin, A.; Xie, Y.; Song, X.; Sun, X. Impact of straw returning on soil ecology and crop yield: A review. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Han, X.; Zhuge, Y.; Xiao, G.; Ni, B.; Xu, X.; Meng, F. Crop straw incorporation alleviates overall fertilizer-N losses and mitigates N2O emissions per unit applied N from intensively farmed soils: An in situ 15N tracing study. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 764, 142884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Dai, S.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, W.; Chen, S.; Meng, L.; Dan, X.; Huang, X.; Cai, Z.; Zhang, J.; et al. Understanding the stimulation of microbial oxidation of organic N to nitrate in plant soil systems. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2024, 190, 109312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, H.; Singh, R.; Bhatia, A.; Jain, N. Recycling of rice straw to improve wheat yield and soil fertility and reduce atmospheric pollution. Paddy Water Environ. 2006, 4, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, S.; Zhu, X.; Cao, G. Effects of Years of Rice Straw Return on Soil Nitrogen Components from Rice–Wheat Cropped Fields. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Zheng, J.; Zhou, M.; Xu, P.; Lan, T.; Kuang, F.; Li, Z.; Yao, Z.; Zhu, B. Crop straw incorporation increases the soil carbon stock by improving the soil aggregate structure without stimulating soil heterotrophic respiration. J. Integr. Agric. 2025, 24, 1542–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Wang, J.; Fang, K.; Cao, L.; Sha, Z.; Cao, L. Wheat Straw Incorporation Affecting Soil Carbon and Nitrogen Fractions in Chinese Paddy Soil. Agriculture 2021, 11, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Li, P.; Wu, W.; Yu, S.; Naseer, M.R.; Liu, Z.; Yu, C.; Peng, X. Integrated Straw Return with Less Power Puddling Improves Soil Fertility and Rice Yield in China’s Cold Regions. Agronomy 2024, 14, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chivenge, P.; Rubianes, F.; Van Chin, D.; Van Thach, T.; Khang, V.T.; Romasanta, R.R.; Van Hung, N.; Van Trinh, M. Rice Straw Incorporation Influences Nutrient Cycling and Soil Organic Matter. In Sustainable Rice Straw Management; Gummert, M., Hung, N.V., Chivenge, P., Douthwaite, B., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 131–144. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, D.; Wu, M.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, F.; Fan, X. Long-term straw returning improve soil K balance and potassium supplying ability under rice and wheat cultivation. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 22260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Experimental Sites | Soil Fertility Grade | Organic Matter (g kg−1) | Total Nitrogen (g kg−1) | Black Soil Layer Thickness (cm) | Soil Fertility Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qianjin Area | High | 46.14 | 1.85 | 29.5 | 13.61 |

| Qianjin Three Area | Medium | 37.17 | 1.43 | 25.1 | 9.33 |

| Qinglongshan Area | Low | 36.8 | 1.40 | 22.3 | 8.21 |

| Experiment | Treatment | Rate of Straw Application (kg ha−1) | Rate of Nitrogen Fertiliser Application (kg ha−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen fertiliser reduction | SN | 8250 | 124 |

| SN0.9 | 8250 | 112 | |

| SN0.8 | 8250 | 99 | |

| SN0.7 | 8250 | 87 | |

| Nitrogen fertiliser addition | N | 0 | 124 |

| SN | 8250 | 124 | |

| SN+ | 8250 | 159 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Q.; Gao, X.; Wu, B.; Li, J.; Liu, X.; Zou, J.; Meng, Q. Fertility-Based Nitrogen Management Strategies Combined with Straw Return Enhance Rice Yield and Soil Quality in Albic Soils. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1964. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15181964

Wang Q, Gao X, Wu B, Li J, Liu X, Zou J, Meng Q. Fertility-Based Nitrogen Management Strategies Combined with Straw Return Enhance Rice Yield and Soil Quality in Albic Soils. Agriculture. 2025; 15(18):1964. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15181964

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Qiuju, Xuanxuan Gao, Baoguang Wu, Jingyang Li, Xin Liu, Jiahe Zou, and Qingying Meng. 2025. "Fertility-Based Nitrogen Management Strategies Combined with Straw Return Enhance Rice Yield and Soil Quality in Albic Soils" Agriculture 15, no. 18: 1964. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15181964

APA StyleWang, Q., Gao, X., Wu, B., Li, J., Liu, X., Zou, J., & Meng, Q. (2025). Fertility-Based Nitrogen Management Strategies Combined with Straw Return Enhance Rice Yield and Soil Quality in Albic Soils. Agriculture, 15(18), 1964. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15181964