1. Introduction

While winemaking is a defining feature of certain regions in Czechia, it is not widespread throughout the country. Few other industries exhibit such a strong territorial association with specific areas—a pattern that holds true throughout Europe.

The primary wine-growing regions in Czechia are Bohemia and Moravia, which have been sub-divided into six sub-regions since 2004. The Moravian wine region includes designated areas for vine cultivation within the historical territory of Moravia and dominates national production, covering more than 17,000 hectares of vineyards. It comprises four wine sub-regions—Mikulov, Velké Pavlovice, Slovácko and Znojmo—and includes 308 officially recognized wine villages. Located near the 49th parallel, these vineyards share a latitude with France’s Champagne wine region and Germany’s top wine regions. According to Chládková [

1], the region is inherently suited for the production of high-quality white wines due to its favorable conditions. Nonetheless, the Moravian region also offers suitable conditions for cultivating red grape varieties. The typical flavor of Moravian wine reflects an earthy authenticity, while preserving its fruity character. With the introduction of advanced winemaking technologies, the properties of these wines are evolving—primarily gaining in finesse and complexity [

1].

The Czech wine-growing region ranks among the northernmost in Europe. The vineyard territory in this region is fragmented, consisting of individual sites situated on sheltered southern slopes at lower elevations. These are primarily distributed along the valleys of the Vltava, Elbe, Berounka, and Ohře rivers, or nestled among the igneous formations of the Bohemian Central Highlands. The fragmented distribution of vineyard sites contributes to significant variability in soil conditions, which affect the extractive qualities and overall character of Czech wines. This is further compounded by considerable year-to-year weather fluctuations, resulting in vintages that alternate between optimal grape ripeness—suitable for appellation-level wines—and less favorable conditions, where wine quality depends largely on the skills and expertise of the winemakers. As Dimitry et al. [

2] emphasizes, “the agricultural sector, especially viticulture, is highly sensitive to changes in the environment, crop conditions, and operational factors”.

The rising standard of living in developed countries, including those within the EU, has led consumers to increasingly prioritize wine quality. A winery’s reputation for quality is closely tied to its winemaking expertise. Wine regions vary significantly in terms of climatic conditions and regulatory frameworks for quality designation [

3]. “Producer brands increasingly dominate global wine markets, while generic advertising promotes regionality and exports” [

4].

Bohemian and Moravian wines are distinguished by their distinct lightness, fruitiness, minerality, and fresh acidity compared to heavier foreign wines. The cultivation and yield of grapevines grown in vineyards is significantly affected by a number of environmental factors [

5]. Individual grape cultivars respond to environmental factors differently in terms of the resulting wine quality [

6], which is reflected in the specific and regionally unique characteristics of the wines [

7]. The specific influence of environmental factors on wine quality is referred to as “terroir” [

8], a concept widely recognized across major wine regions, including France [

9]. The terroir effect refers to the interactions between the grapevines and their natural surroundings and has been recognized as a key determinant of wine quality [

10]. According to Rezende et al. [

11], “environmental factors and the soil microbiome (bacteria and fungi) heavily influence grape quality, shaping the crucial ‘terroir’ for wines”. Today, quality luxury wines are increasingly defined by their terroir, the regional conditions expressed in the wine’s character. Terroir is one of two primary factors influencing consumers’ perception of authenticity and their willingness to pay for it [

12].

Lancaster [

13] posits that consumer utility is derived from the specific quality attributes or characteristics of a product. Consequently, in a differentiated market, products are viewed as a set of quality attributes, with consumers evaluating each characteristic individually, rather than the product as a whole at the point of purchase. Moreover, manufacturers may also consider adopting price competition strategies, as Bertazzoli [

14] identifies high pricing as one of the main limits to further market expansion. As Schätzel et al. [

15] suggest, the profitability of grape production is also important in determining wine pricing. Wine also possesses several unique characteristics that distinguish it from other agricultural commodities, making it a compelling subject of study for economists in general [

16].

The wine industry is currently confronting new challenges, primarily driven by climate change. Ongoing climate shifts and mounting environmental pressures underscore the need to adapt global wine production systems to new climatic realities, while minimizing their environmental footprint [

17]. This phenomenon is reshaping viticulture, as rising temperatures, water scarcity, and changing radiation patterns exert direct impacts on grape quality. To address these challenges, the industry is adopting sustainable practices, including the selection of climate-resilient grape varieties, the implementation of efficient water management, and the adaptation of canopy and soil management techniques [

18,

19]. Prus [

20] further adds that sustainable agricultural development entails programming farming systems to ensure the rational use of natural resources and environment stewardship, while delivering sufficient quantities of high-quality food. The major forces driving the wine market are economic growth and intensified competition, with climate change emerging as a disruptive force [

21].

The identified research gap lies in the potential to develop predictive models for the future of viticulture and grapevine cultivation in Czechia based on current qualitative trends in wine production and consumption.

The aim of this article is to identify and articulate the key qualitative factors that support the future sustainable development of viticulture within the framework of the Czech economy, with particular emphasis on the role and benefits of wine tourism.

3. Results

3.1. Economic Performance in Sustainable Development of Czech Viticulture

3.1.1. Models for the Projected Development of Wine-Growing Indicators in Czechia

Wine production and consumption are closely tied to the tradition of viticulture. In Czechia, numerous relatively small wine-growing regions trace their origins to the Middle Ages.

Table 1 is based on long-term time series data spanning 1993–2023 and presents descriptive statistics of key yield-generating components.

As shown in

Table 1, winegrowing in Czechia represents a sector of primary agricultural production, typically conducted on small plots of land with historical ownership ties. Nearly 86% of growers cultivate plots of land no larger than 0.5 ha. Despite the small scale, the intensive labor, strong family stewardship, and growing consumer interest in regional products have, over time, reinforced connections to the land, the region, and regional food. Since joining the EU in 2004, Czechia experienced a consolidation of large-scale vineyards among a limited number of major growers. By 2023, 79% of vineyards listed in the state register exceeded 5 hectares in size. As shown in

Table 1, individual indicators exhibit limited variability over the long-term time series. However, the long-term perspective and statistical models have revealed breaks in their development, which influence the forecasting of yield-generating components.

3.1.2. Overview of the Basic Model Selection Criteria

All calculations related to the forecasting of indicator development were performed using the methodological framework described above, implemented in the Gretl and SPSS software environments. The calculations were based on long-term time series data spanning 1993–2023. No structural breaks were identified in the time series for total harvest, yield per hectare, or wine production. However, a break was detected in vineyard area in 2006, attributed to the implementation of the EU Common Agricultural Policy. Wine consumption per capita exhibited a structural break in 2014, following its peak in 2012. From that point onward, total wine consumption remained stable throughout the remainder of the observed period.

Table 2 presents the optimal model parameters for forecasting the relevant indicators.

High variability in time series data leads to increased relative deviations from forecasts, raising MAPE values—especially in irregular or volatile series, where small errors can have large proportional impacts.

3.1.3. Cultivated Vineyard Area in Czechia

In 2023, the cultivated vineyard area in Czechia reached approximately 17,750 hectares, while the total production potential stood at nearly 18,100 hectares. As of 31 December 2023, nearly 13,300 grapevine growers were registered in Czechia. The most commonly cultivated white varieties included Green Veltliner, Riesling, Müller Thurgau, and Welschriesling, while the leading red varieties were Blaufränkisch, St. Laurent, Pinot Noir, and Zweigelt.

In 2023, almost 230 hectares of new vineyards were established. The most frequently planted white grape varieties included Pálava (43.37 ha), Gewürztraminer (26.45 ha), and Riesling (26.36 ha). Among the red varieties, Merlot led with 14.49 ha, while Donauriesling was the most planted PIWI variety, covering 11.42 ha.

According to the Central Institute for Supervising and Testing in Agriculture [

33], winemakers will fail to meet the quota for permitted vineyard planting for the fifth consecutive year in 2024. Although the quota allowed for up to 178.3 hectares of new plantings this year, only 84 applications were submitted, totaling 40.5 hectares as of 28 February 2024.

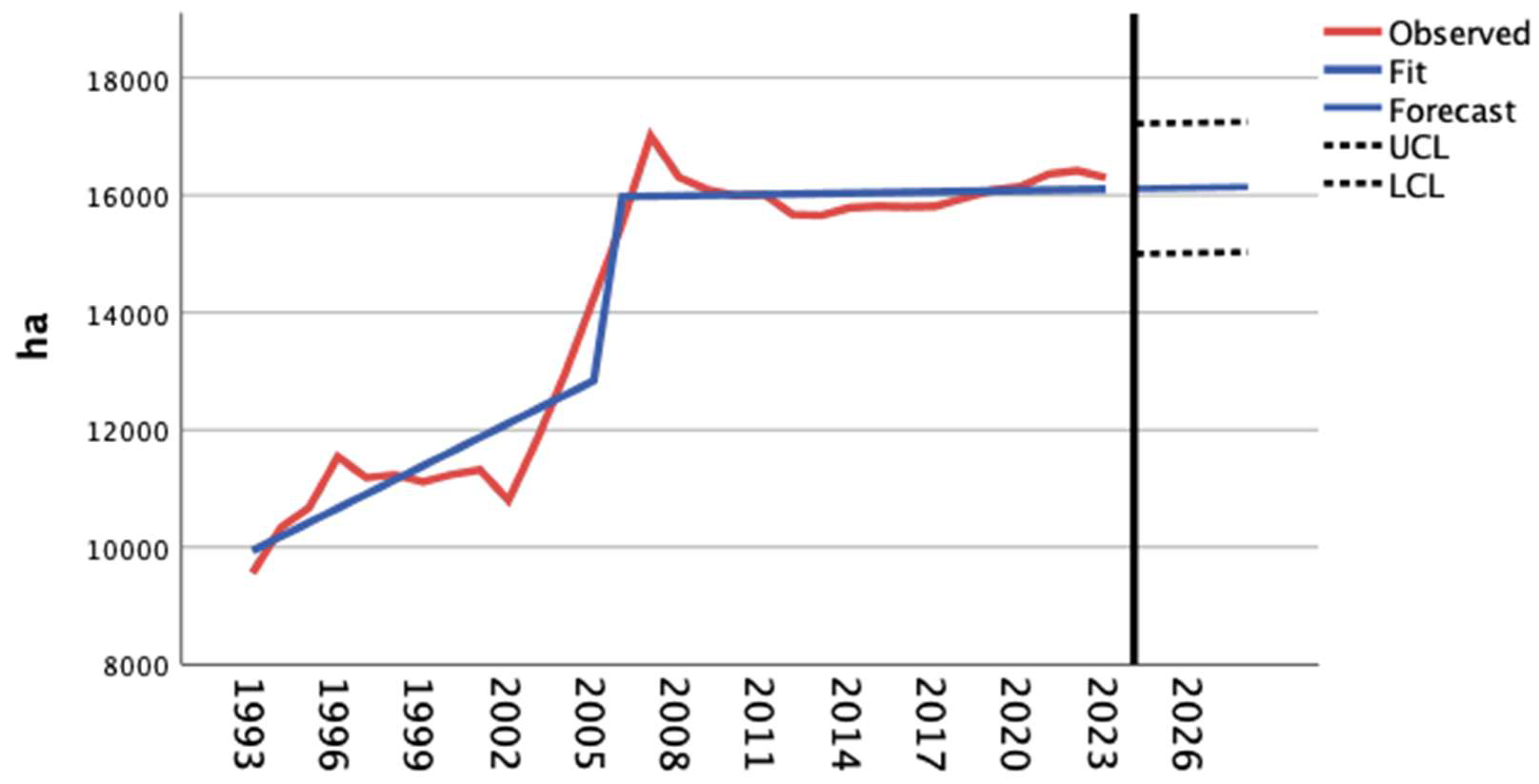

The growing uncertainty among domestic wine organizations is further supported by a 2024 survey conducted by the Wine Union. The findings indicate that the prevailing economic conditions discourage most winemakers from expanding vineyards and renewing vineyard areas, contributing to a gradual decline in vineyard acreage across Czechia. A statistical forecasting model, which identifies a significant structural break in 2004 (see

Figure 1), projects stagnation in the area of vineyards in Czechia.

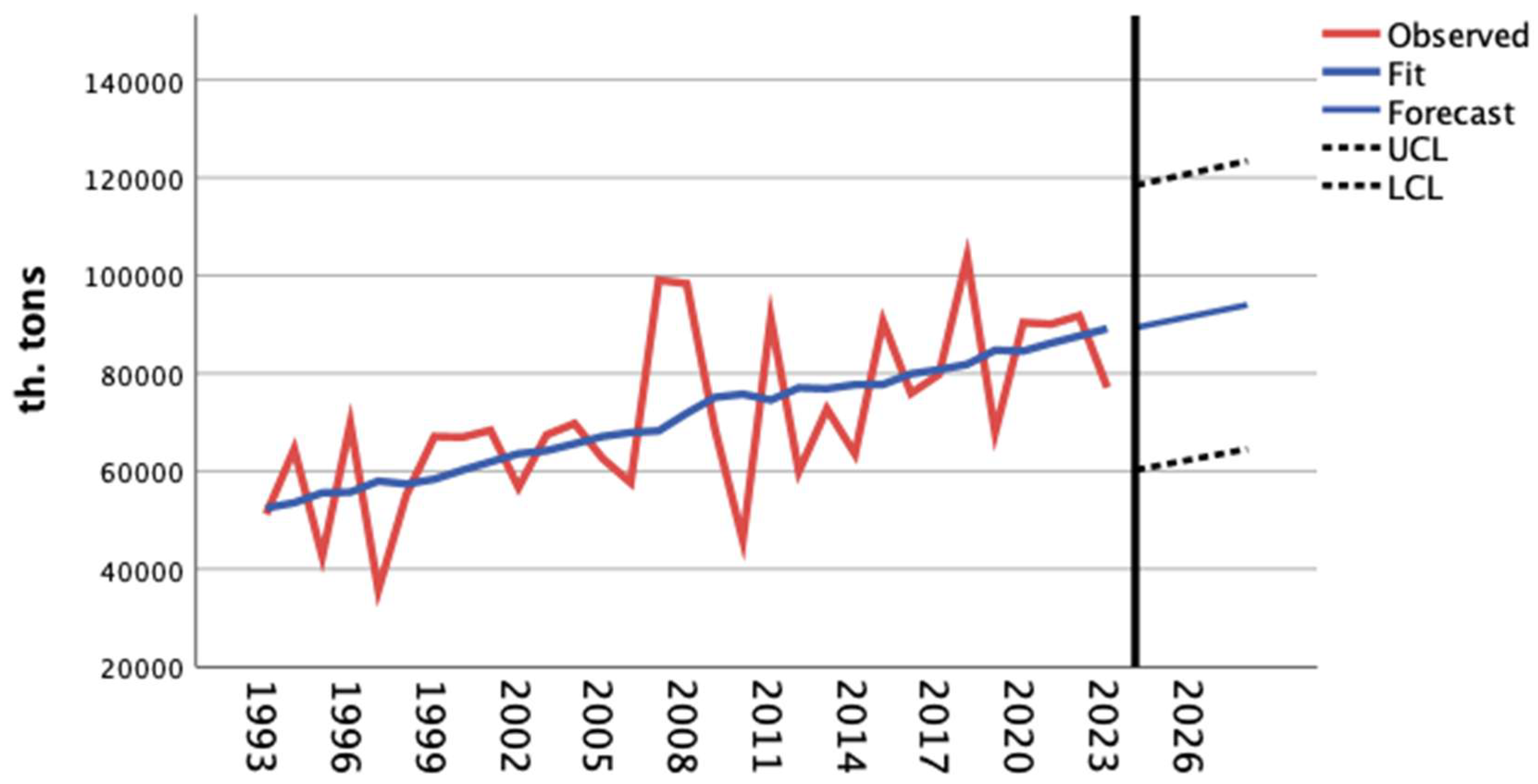

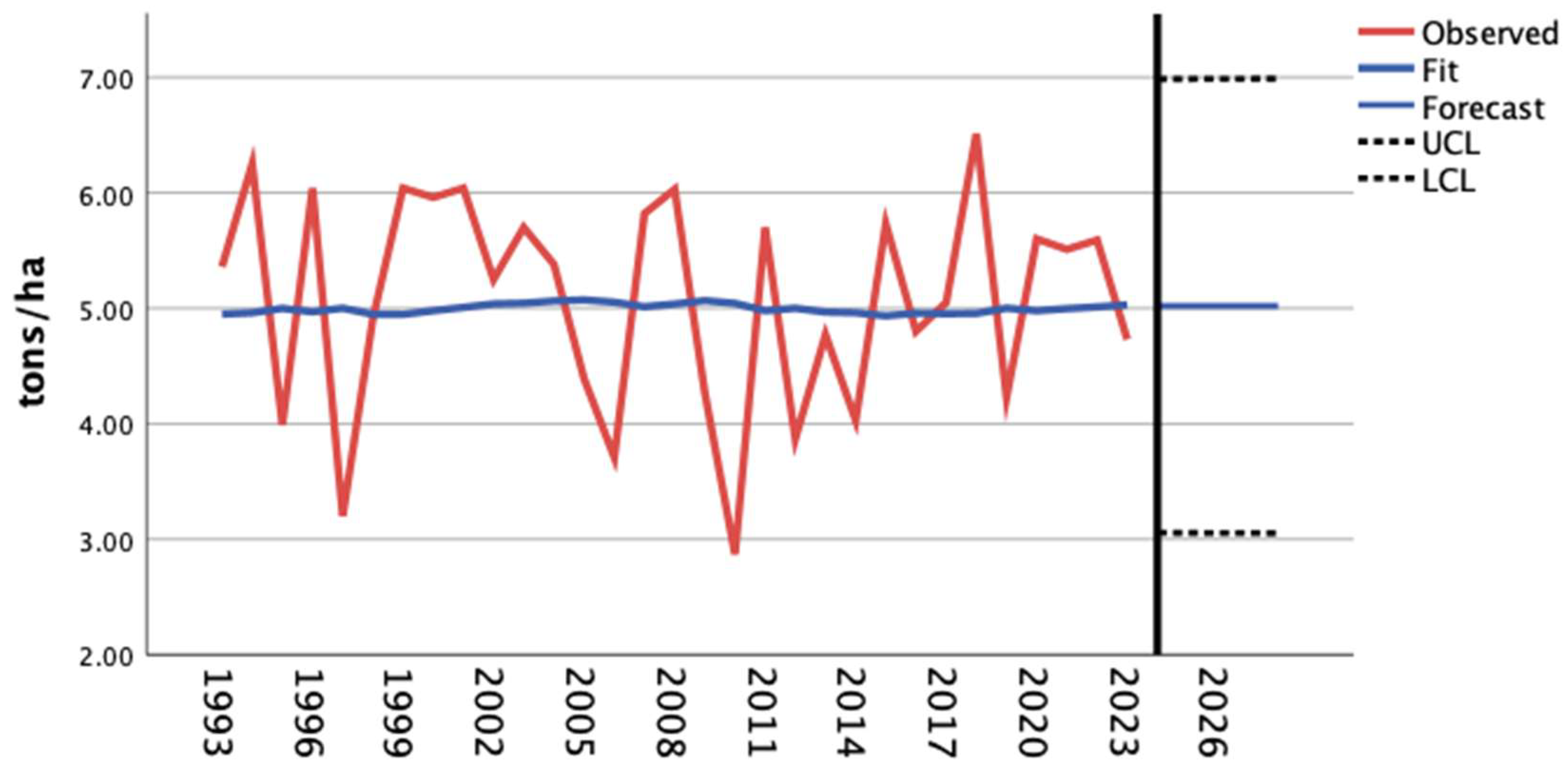

3.1.4. Grape Harvest and Grapevine Yield in Czechia

In 2023, a total of 76,976 tons of grapes were harvested in 2023 in Czechia, representing a 16% decline compared to the previous year. The average grape yield reached 4.73 t/ha, making a 15% year-on-year decrease. The long-term trends in total harvest volume and grape yield are illustrated in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3.

In 2024, grape production in Czechia was significantly impacted by weather conditions, including April frosts, summer drought, and September rainfall. As a result, the volume of harvested grapes declined by a third compared to 2023, with only 1.9 million bottles reaching the market.

“Warm weather at the end of winter and in early spring accelerated the development by up to a month. As a result, April frosts struck during a critical phenological phase”, noted bioclimatologist Martin Možný. This was followed by a prolonged dry summer with extreme temperatures, leading to an exceptionally early harvest in many regions—in some cases as early August, the earliest date on record.

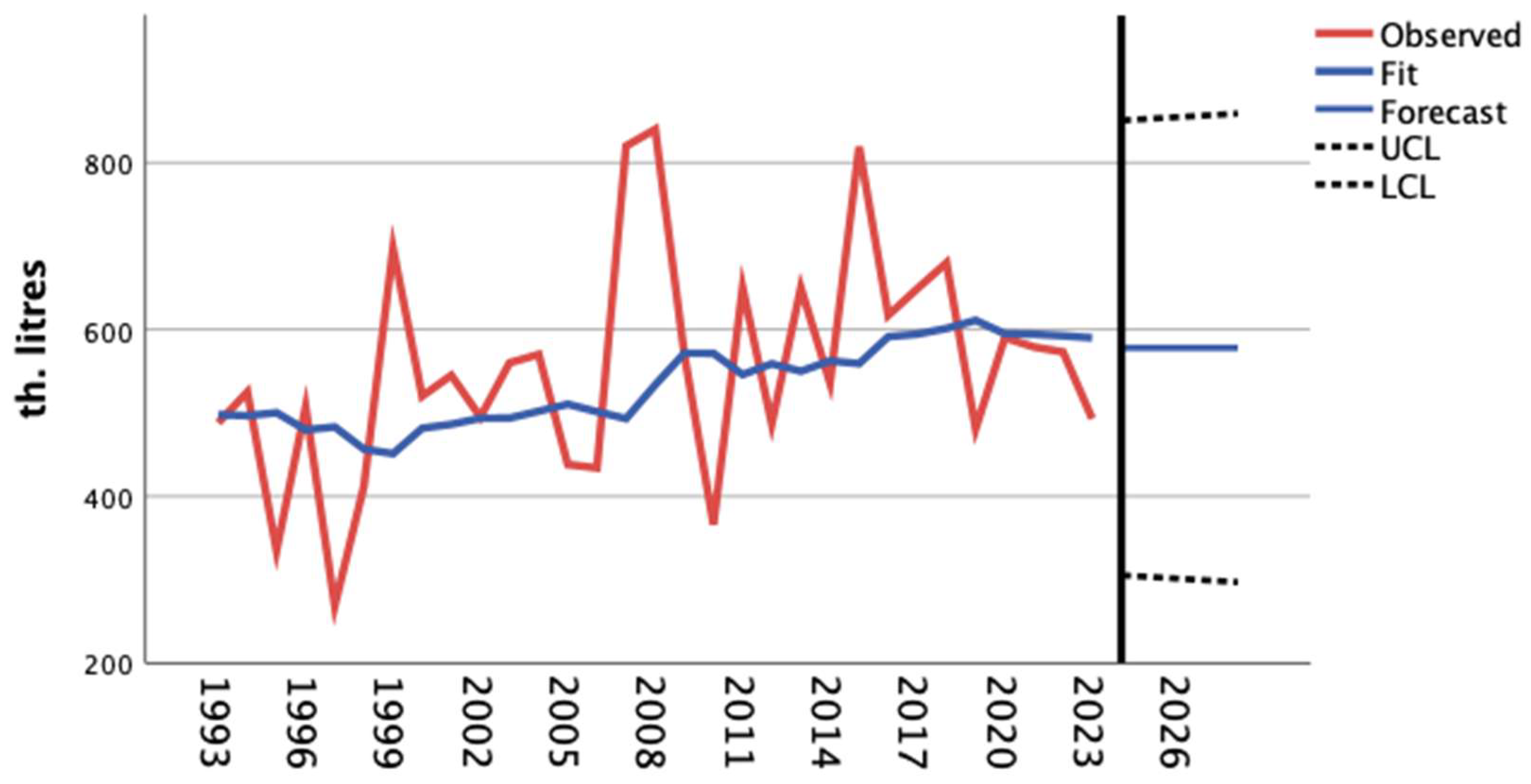

3.1.5. Wine Production in Czechia

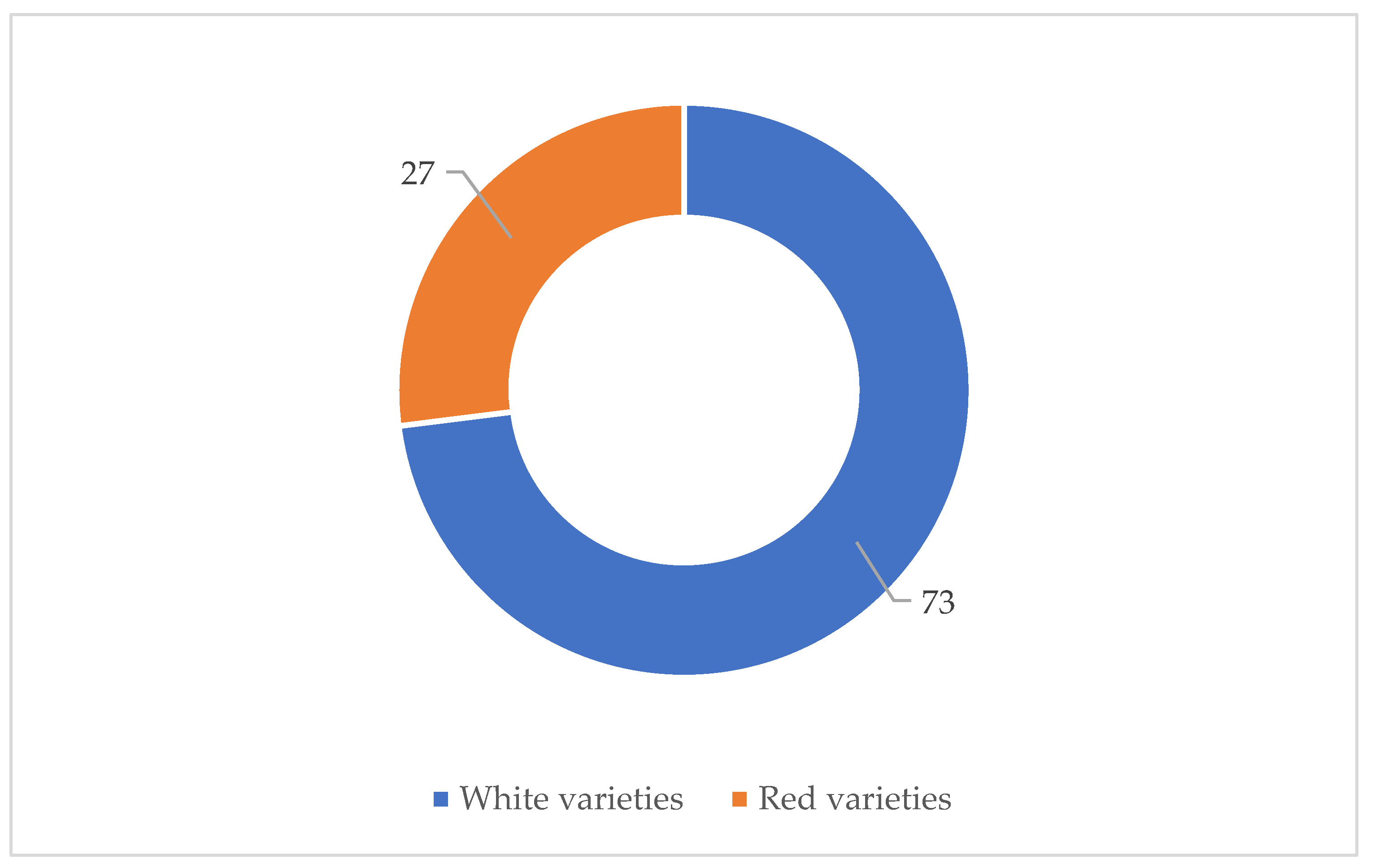

Wine production in Czechia has averaged around 548,000 hL over the past three years (monitored for the wine year, i.e., from 1 August of the calendar year to 31 July of the following calendar year) In the 2023/2024 wine year, total production declined to 493,000 hL. Of the total wine production in Czechia, approximately three-quarters consist of white wine and one-quarter of red wine. Domestic production exhibits considerable long-term volatility, and the mathematical model (

Figure 4) indicates a trend toward stagnation.

On a global scale, wine production consistently exceeds wine consumption, which explains why the wine market is highly demanding, competitive, and increasingly international in scope [

34]. Due to its specific soil and climate conditions, as well as its limited geographical size, Czechia ranks among the smaller-scale wine-growing countries in Europe and, consequently, among the smaller wine producers. While Czechia cannot be compared to countries such as France, Italy, and Spain in terms of vineyard acreage and total wine production (see

Table 3), Bohemian and Moravian winemaking have nonetheless earned numerous prestigious awards at international and global wine competitions.

In 2023, wine production in the European Union totaled approximately 150 million hL, reflecting a year-on-year decline of 11.2 million hL. This volume was 7% lower than in 2022 and 8% below the five-year average. Italy and Spain experienced year-on-year declines of 12 and 14%, respectively, in 2023 [

36].

According to the International Organization of Vine and Wine, global wine production in 2023 fell to its lowest level in sixty years. In Czechia, expected production was 80,000 hL lower than in 2022—a decline of 14%, and 9% below the five-year average.

3.1.6. Total Wine Consumption in Czechia

In 2023, consumption of still wines (i.e., not sparkling or semi-sparkling wines) in Czechia declined by 8.4% [

37]. This downward trend in sales and consumption only confirms the negative forecasts projected in recent months. At the same time, the decline in wine consumption is expected to intensify in 2024, aligning with broader pan-European and global trends. This development has direct implications for the economic sustainability of winemaking enterprises in Czechia.

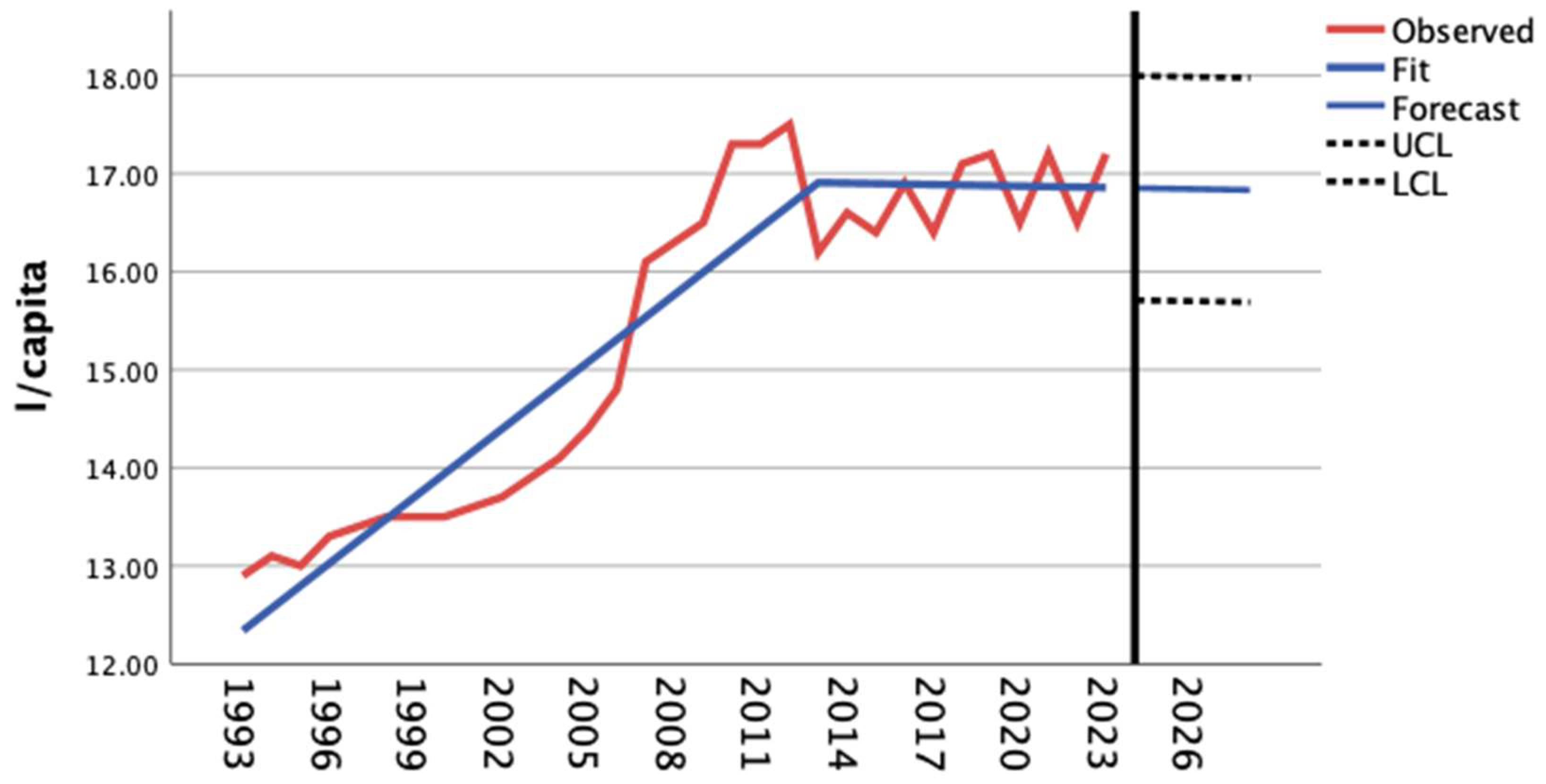

The long-term time series of wine consumption per capita in Czechia (

Figure 5) reveals a significant structural break in 2012. Prior to this point, consumption had increased rapidly; however, since 2012, the trend has shifted to a linear and largely stagnant trajectory. Over the period of 1993–2023, average annual wine consumption in Czechia was approximately 15.35 L per capita (see

Table 1).

The average price per liter of wine rose by just 1% in 2023, positioning still wines among the category with the lowest price increases.

Shifts in consumer behavior and declining interest in wine consumption, especially among younger generations, are evident across EU member states. In Czechia, the cancelation of tax deductibility for still wine as a corporate gift, which came into effect in January 2024, is expected to further contribute to reduced sales in the domestic market.

According to the European Commission’s 2023 market report, wine consumption declined significantly across several major EU countries: by 7% in Italy, 10% in Spain, 15% in France, 22% in Germany, and 34% in Portugal. The International Wine and Spirits Report [

35] reveals that global consumption in the first half of 2023 dropped by nearly one-sixth compared to the same period in 2019.

3.1.7. Forecasting Key Indicators of the Czech Viticulture Sector

Long-term development trends have reshaped the current landscape of the Czech viticulture sector. The sharp expansion of vineyard acreage up to 2006 (

Figure 1) led to a corresponding increase in total grape harvest (

Figure 2). However, year-to-year variability in climatic conditions has significantly affected yield per hectare (

Figure 3), thereby influencing overall domestic wine production (

Figure 4). The forecasts presented in

Table 4 are highly responsive to long-term trends and suggest a stagnation of the entire sector in the coming years.

According to the selected models (

Table 2), projections for the next three years indicate growth only in vineyard area and total harvest. In contrast, yield per hectare, per capita wine consumption, and overall wine production in Czechia are expected to remain stagnant.

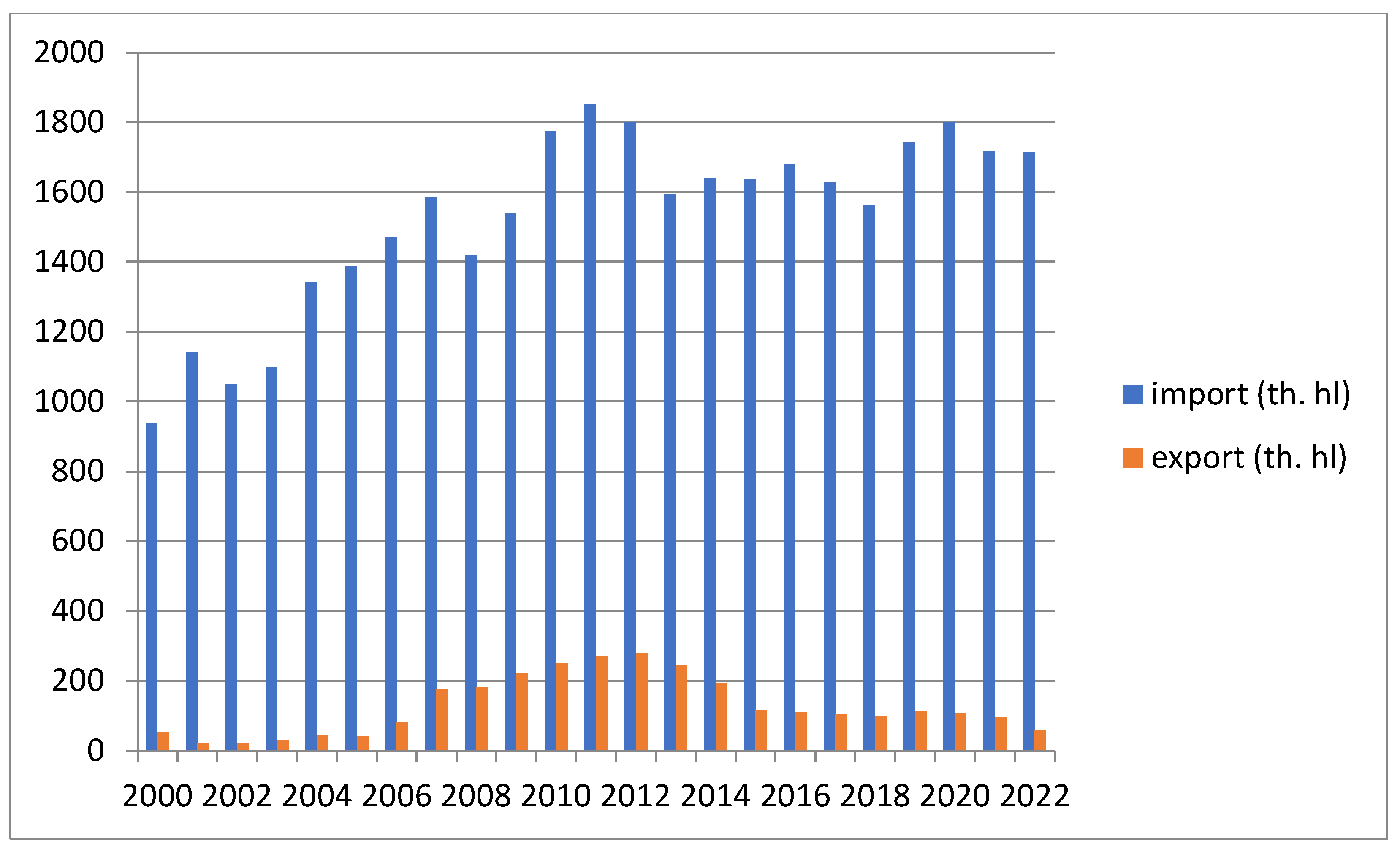

3.2. Czech Foreign Trade in Wine

In 2012, Czechia imported 1.8 million hL of wine products and exported a record 280,000 hL. By contrast, in 2022, imports totaled 1.714 million hL, while exports fell sharply to just 59,000 hL (

Figure 6). Imports in 2022 approximately matched the volume recorded in 2011. However, the significant decline in exports was primarily attributable to adverse climatic conditions during the growing season.

Prior to Czechia’s accession to the EU, wine exports were minimal due to restrictive trade quotas and tariffs imposed by neighboring countries. Following EU membership, these barriers were eliminated, leading to a surge of inexpensive wines from Spain or Italy. In response, Czech winemakers sought success in foreign markets [

38].

In 2022, Czechia imported the largest volumes of wine from Italy, Spain, and Hungary. Among non-EU countries, Moldova, Chile, and South Africa accounted for the most significant shares. Wine exports from Czechia totaled only 59,000 hL, with Moravian and Bohemian producers primarily targeting Slovakia and Poland as their main export destinations.

3.3. Qualitative Aspects of Sustainable Viticulture Development

3.3.1. The Popularity of Dry Wines and Their Culinary Applications

Historically, Czechia has exhibited a distinct preference for wines with residual sugar, setting it apart from global consumption patterns. However, in recent years, this trend has shifted markedly, with Czech consumers increasingly opting for drier and more complex wines. This is also reflected in the culinary use of wine [

39].

Offering optimum wine and food pairing is no longer the exclusive domain of luxury restaurants. Increasingly, establishments in the mid-price segment are embracing this practice, reflecting one of the most prominent trends in contemporary Czech gastronomy. Many restaurants now curate special tasting or seasonal menus, carefully matching selected wines with individual courses to achieve the most harmonious combinations. Seasonality plays a vital role in Czech gastronomy, particularly during periods such as asparagus season or venison feasts. As sommeliers note, “these are menus where dishes can be paired very well with different types of wine” [

40].

Over the past decade, Czechia has made substantial progress in the fields of gastronomy and related professional disciplines. The emergence of highly skilled experts in these areas has significantly elevated the quality and reputation of local culinary culture [

40].

3.3.2. Representation of Czech Winemakers in Retail Chains

In recent years, the Czech retail sector has undergone consolidation, resulting in a market dominated by several large commercial corporations. These entities, operating in an oligopolistic environment, exert downward pressure on wine prices and impose demanding delivery conditions on domestic producers. In addition, as all major retail chains are foreign owned, they tend to prioritize wines from their countries of origin.

Despite these challenges, Moravian and Bohemian winemakers continue to supply their products to domestic retail chains. Although navigating these partnerships is demanding, retail chains remain an indispensable distribution channel for Czech winemakers. The share of local wines in retail offerings ranges from 40% to 70%, and the number of wineries participating is steadily increasing—with approximately 13 producers currently supplying wine to Kaufland. Overall, total wine sales are on the rise. According to estimates by the Czech Winegrowers Association, retail wine sales are growing at approximately 8% annually. This trend is not limited to the largest producers; in recent years, several smaller winemakers—such as Patria Kobylí and Oldřich Drápal—have entered retail chains. However, due to their limited production volumes, these smaller suppliers face weaker bargaining positions compared to larger suppliers.

Unlike many other consumer goods, wine benefits from strong origin-based preferences. While customers may not distinguish between apples from Czechia and those imported from Hungary, wine is increasingly purchased based on provenance. Moravian wine, in particular, enjoys high demand due to its perceived quality, prompting retail chains to prioritize its presence on store shelves.

Given that approximately 65–75% of all wine consumed in Czechia is sold through retail chains, it is evident that winemakers remain committed to this distribution channel despite lower profit margins. Notably, in 2004, several producers openly opposed retail partnerships; however, today, many of them have successfully placed their wines on store shelves.

Vinselekt Michlovský—Winery of the Year 2010—also supplies its products to retail chains. Negotiations regarding its entry into one such chain reportedly lasted seven years before mutually acceptable terms were reached. However, for winemakers, it is virtually impossible to sell more than 150–200 thousand liters of wine profitably without engaging with retail chains; at lower delivery volumes, the sales price fails to cover production costs [

41].

In 2016, Znovín Znojmo achieved one of the highest profits in its history, despite significantly reducing its wine sales through large retail chains. This strategic shift proved highly successful, with the company earning a net profit of 49 million CZK.

While Znovín’s higher quality wines remain available in supermarkets, the company is increasingly shifting toward its own distribution channels—including direct sales, an on-line store, and delivery services. This strategy has proven effective, as the share of individual consumers purchasing directly from Znovín continues to grow. Moravian wines are best positioned in the mid- and upper-tier segments; in the lower price categories, they struggle to compete with cheaper foreign imports [

42].

3.3.3. Expansion of Wine Shops in Czechia and Improvement in Wine Market Quality

The number of wine shops in Czechia surpassed 6000 in 2018, up from nearly 5200 in 2016. According to data from the Czech Agriculture and Food Inspection Authority (CAFIA) [

43], this upward trend has continued, despite the amendment to the Wine Act—a legislative change that faced considerable opposition from winemakers.

The amendment, which came into effect on 1 April 2017, aimed to curb malpractice among cask wine sellers in particular—including practices such as dilution with water, artificial sweetening, and misrepresentation of origin. It introduced a mandatory reporting requirement to the Vineyard Register maintained by the Central Institute for Supervising and Testing, thereby establishing clear accountability for the quality and safety of bulk wines. Additional obligations were implemented under CAFIA oversight [

43].

The Ministry of Agriculture [

23] has expressed satisfaction with the legislative amendment, with spokesman Vojtěch Bílý stating that “the amendment contributed to the improvement of the wine market”. This view is echoed by Bohemia Sekt, a leading producer of sparkling and still wines, whose director, Ondřej Beránek, affirmed: “It is a step in the right direction; the amendment significantly contributed to the improvement of the market environment”.

The positive impact of the legislative amendment is supported by CAFIA data [

43], which indicate a significant decline in regulatory violations. Between 2013 and 2016, the proportion of non-compliant wine samples ranged between 35% and 43%; following the amendment, this figure decreased by approximately half (CAFIA). Nonetheless, wine remains among the most problematic commodities in terms of compliance, ranking just behind honey and meat products [

44].

3.3.4. Supporting the Success of Czech Wines Abroad

In 2020, winemakers from Moravia and Bohemia saw record-breaking performance at international competitions, securing 1100 medals and 28 champion titles—the latter awarded to wines of exceptional quality. According to the Wine Fund [

45], which financially supports Czech participation in these events, this marked an 11.1% increase compared to 2019, when Czech producers earned 990 medals.

Czech winemakers earned 29 large gold medals and 20 platinum medals, despite pandemic-related rescheduling.

Among the international competitions in which it participated, B/V winery from Ratíškovice achieved exceptional success in 2020. At the Concours Mondial de Bruxelles in Brno, it was awarded the title for the best white wine of the competition. At Le Mondial des Vins Blancs Strasbourg, it won the title for the best dry white wine. The winery also secured 27 medals at the Mundus Vini competition in Germany, 30 medals at the Hong Kong international competition, and earned a champion title at Terravino in Israel [

46].

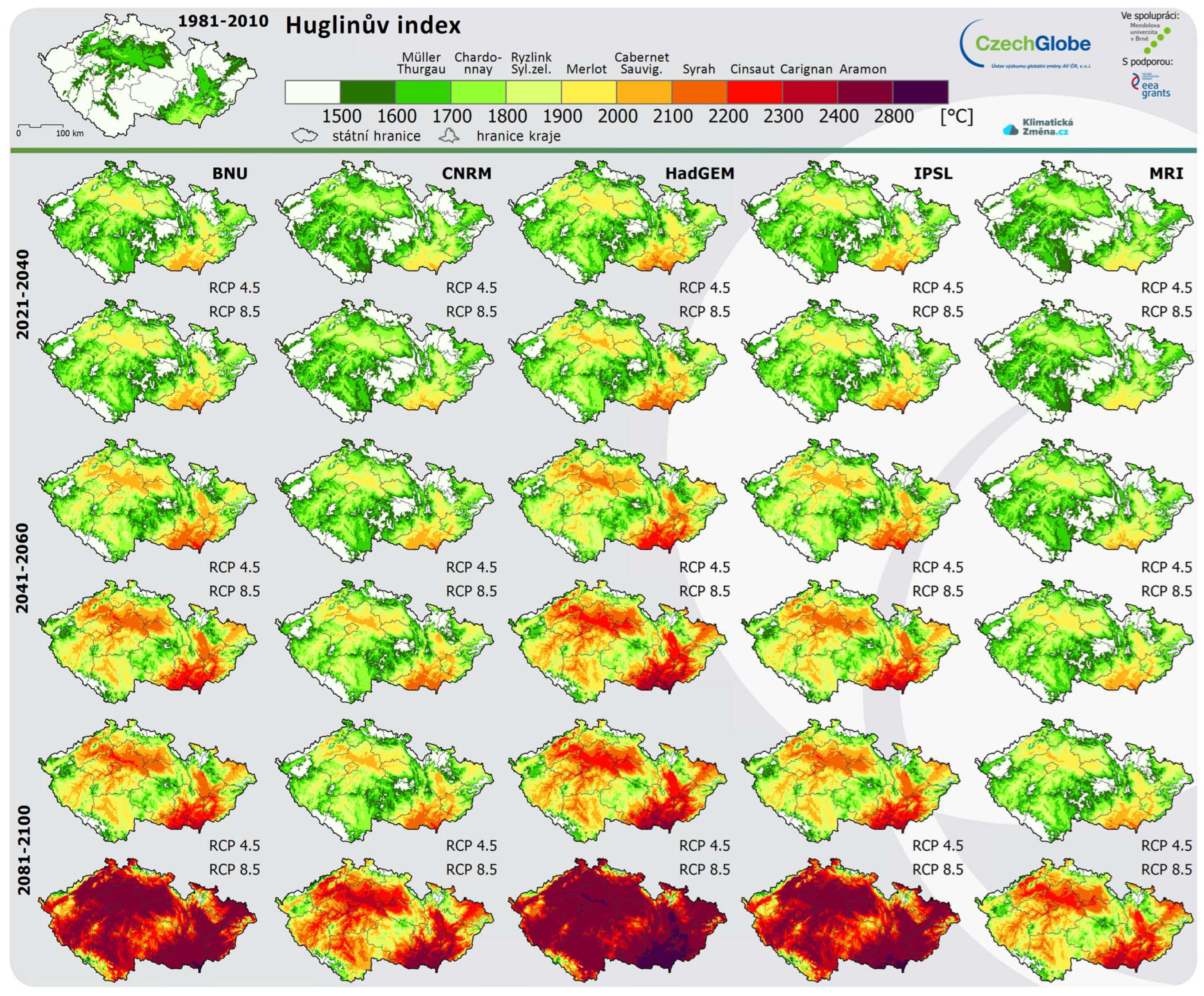

3.3.5. Adaptation to Climate Change

Climate change is increasingly influencing grape yield, composition, and overall wine quality, prompting a shift in the geographical distribution of wine production [

47].

Figure 7 illustrates this transformation, with the top left panel depicting Czechia under its historically prevailing climatic conditions. To the right of the map of Czechia, a color scale displays the names of individual vine varieties, indicating their cultivation suitability based on specific Huglin Index values. The rows below present long-term projections generated using major climatological models—BNU, CNRM, HadGEM, IPSL, and MRI—covering the entire 21st century. Each time period and model include two scenario variants [

39].

Over the past 60 years, the average temperature in the South Moravian Region—Czechia’s primary wine-growing area—has risen by approximately 1.5 °C. Climatologists project that this warming trend will persist in the coming decades, with notable impacts including prolonged heat waves and reduced precipitation.

The forecast presents unfavorable conditions for consumers of South Moravian white wine. Insufficient rainfall during the summer growth phase leads to nitrogen deficiency in the soil, which in turn impairs fermentation and aroma development. Moreover, when precipitation occurs as torrential downpours amid prolonged dry spells and extreme temperatures, the risk of mold formation in white grape varieties increases significantly.

Winemakers are actively adapting to climate change and employing all available strategies to protect traditional grape varieties in South Moravia. “We are gradually including PIWI varieties in our plantings that are characterized by higher resistance to diseases and extreme weather fluctuations”, stated Petr Chaloupecký, director of the Lahofer Winery in the Znojmo region.

In response to climate challenges, Thaya Winery in the Znojmo region ensures that newly established vineyards feature noble grape varieties grafted onto rootstocks with enhanced resistance to elevated temperatures and drought. This adaptive measure is also employed by Miloš Michlovský, a leading expert in grapevine breeding and owner of Vinselekt in Rakvice, located in the Břeclav region.

However, experts caution that these measures will remain effective only as long as climate change exerts limited influence. As the warming trend intensifies, they warn that white wine production may become increasingly difficult—potentially to the extent that future demand can no longer be met under traditional viticultural conditions.

Other experts suggest that rising temperatures may enable viticulture in colder regions previously considered unsuitable. According to several climate models, Central Moravia could develop ideal conditions in the coming decades for the cultivation of at least five grape varieties, particularly white ones such as Müller Thurgau, Chardonnay, and Riesling. According to several climate models, a 2 °C temperature increase could create suitable conditions for cultivating the Merlot variety even in the Bohemian Central Highlands in the northwest of Czechia.

According to the aforementioned researchers, South Moravia, which is one of the warmest regions in Czechia, is projected to become increasingly suitable for red wine production as temperatures continue to rise. This marks a shift from its present focus on white wine cultivation [

39]. Projections indicate that if the current trend of rising temperatures continues, adjustments in viticultural practices will be necessary to maintain grape cultivation suitability in the studied area [

49].

According to winemakers, current consumer preferences strongly favor white wine, with an estimated ratio of 80% white to 20% red (for comparison with production data see

Figure 8). Winemaker Miloš Michlovský asserts that Moravia is fully capable of producing high-quality red wines, stating: “And whoever says no, does not know how to do it and does not want to admit it”. Michlovský emphasizes the need to plant grape varieties in locations that offer optimal conditions for producing high-quality wines, as Czechia cannot compete with foreign producers in the segment of low-cost red wines. Favorable vintages for red wine occur only occasionally; 2005 and 2006 were considered successful, while 2009 and 2018 were regarded as exceptional.

3.3.6. Wine Tourism

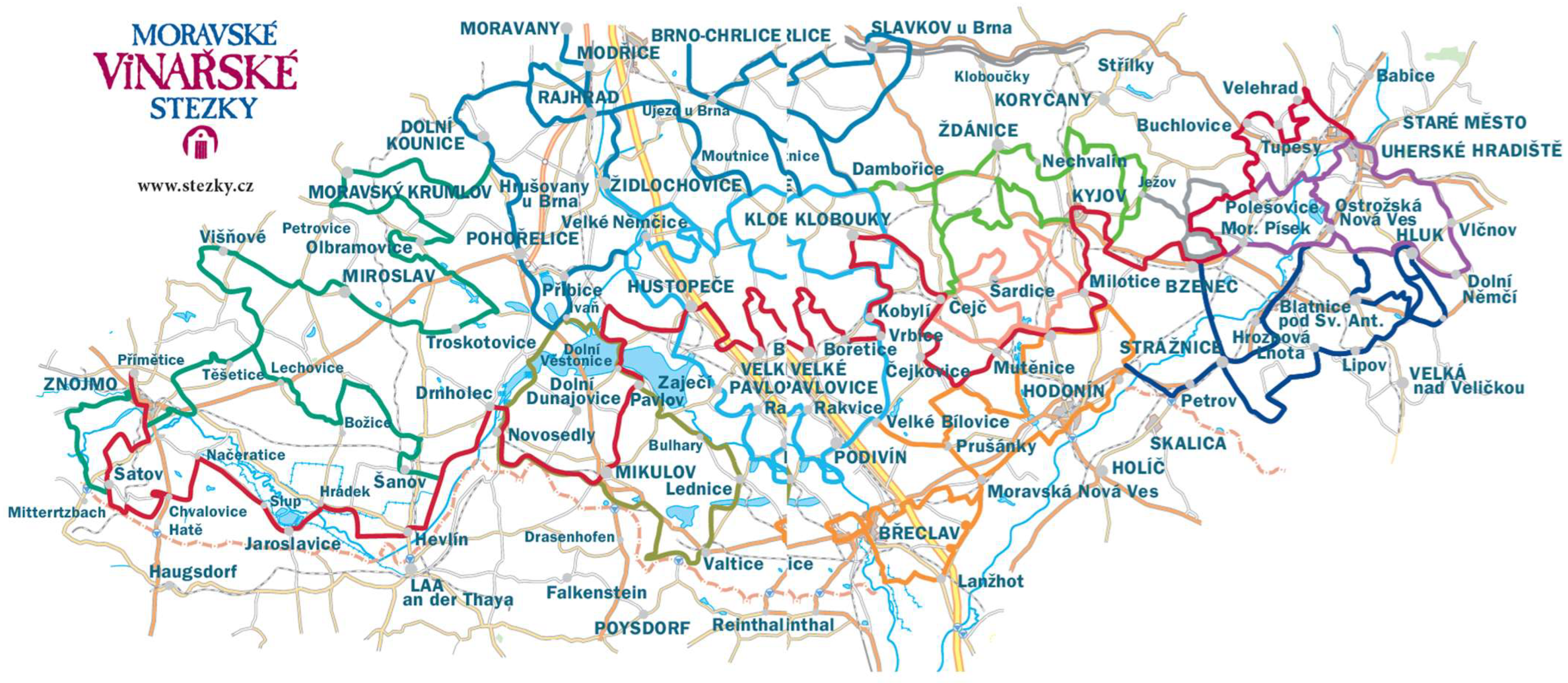

Czechia comprises two official wine regions—Moravia and Bohemia—sub-divided into six sub-regions. These encompass 383 wine-growing municipalities and 17,764 hectares of vineyards across 1309 vineyard tracks, cultivated by over 18,000 growers. Approximately 96% of vineyards are located in Moravia, with the remaining 4% in Bohemia. White grape varieties account for 69% of the total planted area. The sector includes around 850 registered wineries—ranging from large enterprises to small family-run businesses—and thousands of private growers. The Moravian wine region (308 municipalities, 17,091 ha) consists of four sub-regions as follows: Znojmo (90 municipalities, 3083 ha), Velké Pavlovice (70 municipalities, 4814 ha), Mikulov (30 municipalities, 4841 ha), and Slovácko (118 municipalities, 4353 ha). The Bohemian wine region (75 municipalities, 673 ha) includes the Mělník sub-region (40 municipalities, 360 ha) and the Litoměřice sub-region (35 municipalities, 313 ha) (see

Figure 9) [

50].

Viticulture in Czechia

Wine consumption is on the rise in Czechia, accompanied by the growing popularity of wine tourism. Visitors can choose from a wide range of wine-related establishments. A guaranteed standard of service—including foreign language proficiency—is offered by wineries, wine cellars, wine shops, restaurants, and accommodations certified under the national wine tourism program. Many of these certified wine tourism venues can be encountered while exploring the dense network of wine trails in the region. Numerous educational wine trails lead directly through vineyards or focus on specific grape varieties. Visitors are also encouraged to explore Moravian cellar lanes, which can be navigated with the help of a dedicated mobile app. The scenic wine-growing landscape can even be admired from above—thanks to a series of recently constructed lookout towers, one of which is uniquely shaped like a wine glass. If one takes a deeper interest in the history of winemaking, the interactive exhibition on Czech and global viticulture at Mikulov Castle is not to be missed. Visitors should also take the opportunity to sample local grape varieties, such as Pálava, Moravian Muscat, André, and Cabernet Moravia [

50].

Certification of Wine Tourism Services

Wine-growing regions in Czechia, with their mosaic of vineyards, cycling trails, cellar lanes, wine cellars, and wine shops, attract thousands of visitors each year. But how can one navigate the range of available services? Where are wines offered for tasting, which wineries welcome guests warmly, and where is the best place to stay? The advice is simple: look for certified venues.

77 Certified Wineries

A certified winery must offer a portfolio consisting of at least 90% domestic wines from a minimum of six grape varieties, including those typical of the region. At least part of the selection is classified by the State Agricultural and Food Inspection Authority (SZPI), which carries the VOC designation or has received awards from selected national competitions. Visitors are also offered tours of the vineyards or cellar facilities. Wine and packaging materials are readily available for purchase.

84 Certified Wine Cellars

The wine selection offered by a certified cellar follows the same rules as those for certified wineries, with the exception of competition awards. Guests can enjoy guided tastings and additional programs. Wines are served in appropriate glassware and accompanied by a choice of hot or cold refreshments. Certified cellars feature simple, clean furnishings and provide standard sanitary facilities.

40 Certified Lodging Facilities

Certified accommodations differ from standard hotels and guesthouses through their clear connection to winemaking and wine culture. These establishments are located either directly within a winery or adjacent to a wine cellar, wine shop, or wine-focused restaurant, and their capacity does not exceed 50 beds. Staff are able to provide information about regional viticulture as well as an overview of key tourism and wine-related services and events. Cleanliness and buffet-style breakfast are standard features.

Moravian Wine Trails

A unique 1200 km network of marked cycling trails spans all sub-regions of South Moravia’s wine country. The project, coordinated by the Partnership Foundation, involves 250 wine-producing municipalities. Routes for individual circuits as well as the central Moravian Wine Trail are mapped with details on length, elevation profile, and surface conditions. Points of interest and services along the way are indicated by information panels and directional signs with pictograms.

The Moravian Wine Trail

The red-marked backbone route of the Moravian Wine Trails connects the historic town of Znojmo with the Slovácko capital, Uherské Hradiště. This 292 km-long corridor passes through all Moravian wine sub-regions and intersects seven of the ten local wine trail circuits. Along its path lie 70 wine-producing municipalities and ten protected natural sites (see

Figure 10).

The Importance of Wine Tourism in Czechia

In South Moravia, where wine is woven into the cultural fabric, places like Mikulov and its surroundings saw up to 27% of domestic and 42–43% of international visitors enhance their stay in 2024 through culinary experiences and wine tasting. To put things in perspective, in the previous year, less than 12% of Czech visitors and 24.5% of foreign tourists explored the region through food and wine. Back in 2019, the numbers were notably higher—over 29% and 41%, respectively [

51].

According to a 2012 survey by the Wine Fund [

45], 15% of Czechs—and 19% of wine enthusiasts—traveled to South Moravia with wine tourism as their main purpose.

3.4. Research on Wine Consumption in Czechia

A recent survey conducted by the Wine Union of the Czech Republic [

52], which represents nearly thirty domestic wineries, found that current conditions are discouraging most producers from expanding vineyard acreage or restoring existing plots. This trend is contributing to a gradual decline in cultivated vineyard area.

According to Ondřej Beránek, President of the Wine Union of the Czech Republic, “the wine industry is highly sensitive to changes and requires long-term strategic planning. For example, when establishing a new vineyard, the first harvest typically occurs only after four years. Given the current level of uncertainty, the associated risks are so significant that most winemakers are unable to commit. Many are resorting to grubbing and deferring the renewal of existing vineyards as they are unsure whether the grapes will even be needed”, he stated, adding that one of the most pressing challenges facing domestic viticulture is the ongoing decline in available labor.

Our current findings align with the results of the Wine Union’s survey. Employment in viticulture is not in high demand, and the number of available positions exceeds the pool of job seekers. The most significant challenge lies in seasonal vineyard work, prompting winemakers to rely heavily on specialized viticulture machinery. However, a persistent issue remains: the shortage of qualified personnel to operate this equipment.

This situation placed all companies engaged in wine production under considerable strain. “These are companies specialized in the wine industry, which is highly specific. As a result, it is difficult for most of them to reorient toward another sector”, stated Pavel Buchta of Vinařský ráj, one of the leading suppliers of winemaking technologies in the Czechia and Slovakia.

In March 2024, the Grapevine Breeders’ Association officially ceased its operations. The primary reasons cited were the advanced age of its members and declining interest in grapevine breeding among younger generations. “Over the years, we have witnessed the decline of floriculture, vegetable cultivation, and fruit growing. Now, it appears that viticulture is facing the same fate. All around us, vineyards are being grubbed up. In such an unstable environment, long-term planning is impossible”, stated Alois Tománek, grapevine breeder and former chairman of the Grapevine Breeders’ Association. Due to the uncertain outlook for the industry, Vinofrukt—the largest domestic producer of grapevine seedlings—has also ceased operations. “In recent months, winemakers have shown no interest in new plantings, and as a result, we were forced to discontinue seedling production after seventy years”, stated Marek Šťastný of Vinofrukt.

Certainty remains the foremost demand among winemakers. “We do not seek benefits, exemptions, or special subsidies. What we require are stable and equitable business conditions—comparable to those enjoyed by neighboring wine-producing countries and derived from harmonized EU legislation”, stated Martin Chlad, President of the Winegrowers Association of the Czech Republic.

4. Discussion

The following topics are considered fundamental to the discourse on the sustainable development of viticulture and grapevine cultivation in Czechia.

4.1. Qualitative Shifts in the Winemaking Business

The viticulture landscape of Czechia also includes successful modern wineries led by dynamic entrepreneurs. Despite recent years being marked by external challenges largely beyond their control, they continue to thrive.

“We encounter numerous challenges in wineries on a daily basis, much like other agricultural entrepreneurs. However, as Young Winemakers, we do not subscribe to the narrative of complaint but focus on seeking solutions. We operate in a country where, unlike our neighbors, there is no state support for domestic production—and that is the greatest disappointment we, as Young Winemakers, face”, stated the association of twelve winemakers, all of whom are under the age of 40.

“In 2024, spring frost impacted production for the first time since the company’s founding in 2017. Notably, the vineyard at the Baťa Canal experienced frost damage for the first time since it was planted in 2019. The damage was extensive—estimated at approximately 90%. Our other vineyards in Blatnice pod sv. Antonínkem suffered average losses of 20%”, stated Tomáš Zbořil, Executive Director of the Dog in Dock winery. Established as a project of the Trigema Travel development company, the winery continues to pursue innovative approaches despite these setbacks. “We are committed to finding new solutions. That is why we launched the first phase of the Dog in Dock complex this year, offering accommodation in stylish apartments and a bistro featuring regional specialties”, he added [

36].

The challenges faced by certain Czech wineries stem not only from sub-optimal strategic decisions but also from the burden of excessive legislation. In viticulture, the legal framework comprises approximately 700 pages of standards, in stark contrast to the brewing industry, for example, which is governed by just 15 pages of legislation.

4.2. Decline of Wineries in Czechia

Wineries in Moravia are experiencing a marked decline. Some have ceased operations entirely, while others are being offered for sale due to economic pressures or family-related circumstances. Many old winemakers lack successors within their families and are unable to secure external investors. At present, finding a buyer for an existing winery is virtually impossible.

Currently, approximately a dozen wineries are listed with real estate agencies. “Many others—particularly smaller producers and independent tradesmen—are contemplating the cessation of operations”, stated Martin Chlad, President of the Winegrowers Association of the Czech Republic.

“It previously took six to nine months to sell a winery, and I typically completed two sales per year. However, over the past three years, I have not succeeded in selling a single one. There are no investors or interested parties”, explained Robert Schmidt, owner of Schmidt Reality, a company specializing in winery sales. “Sales are now conducted privately, as winemakers fear that public listings could undermine consumer confidence and destabilize their sales teams. Prices range from tens to hundreds of millions”, he added [

36].

4.3. Family Wineries and New Sales Opportunities

“Family-run wineries that are gradually passed down to the next generation tend to perform best. Those who lack such continuity often face no alternative but to sell”, stated Jan Jordán, real estate broker and owner of ERA for Live. He further noted that most successful wineries are diversifying their operations. “They host winery events, develop their guest accommodations, and produce low-alcohol wines or related products to maintain activity and sales during periods of stagnation”.

Chateau Valtice is actively seeking new sales avenues. In recent years, the proportion of direct-to-consumer wine sales has increased notably, prompting the winery to focus on its investment strategy accordingly. In 2016, it constructed a new wine shop—the Wine Barn—in Valtice at a cost of approximately 60 million CZK, designed to attract hundreds of visitors annually. The winery has also expanded its e-commerce presence. While wholesale remains a relevant channel, it is increasingly dominated by low-cost imported wines [

53].

4.4. Withdrawal from Retail Chain Partnerships

Economic considerations are a key factor discouraging wineries from partnering with retail chains. “They pressure us into pricing structures that do not reflect the value we place on our wines”, confirmed Daniel Smola, Marketing Director of the Lahofer winery in Znojmo. Consequently, the winery has opted not to collaborate with chains such as Kaufland or Tesco.

The Lahofer winery positions itself as a producer of high-quality wines and maintains elevated standards for its distribution partners. Sellers are expected to meet stringent criteria regarding sales practices, storage conditions, and overall presentation. Such standards cannot be maintained in supermarket environments. Moreover, according to Smola, supermarkets pose a reputational risk to wineries. “If we started selling in supermarkets, many of our business partners from wine shops or the gastronomy sector would stop buying from us—precisely because we would be available everywhere” he explained [

54].

The shift away from retail chains reflects broader international trends. In Czechia, approximately 17,000 hectares of vineyards are currently in production, yielding a volume of wines that satisfies around 40% of domestic demand. As a result, local winemakers are not compelled to accommodate the pricing pressures imposed by retail chains. This is particularly relevant for small and medium-sized wineries, which have enjoyed a notable rise in popularity and consumer interest in recent years. Nevertheless, large-scale producers will continue to rely on retail partnerships to maintain distribution volumes.

4.5. Summary of Research Findings

A welcome sign for the future of Czech winemaking and viticulture comes from recent research into performance indicators, along with statistical forecasts pointing to continued stable growth in the sector.

To assess the qualitative factors shaping winemaking and viticulture, the following SWOT analysis outlines the sector’s strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (see

Table 5).

The findings outlined in individual chapters confirm that the claims made by cited experts in winemaking and viticulture accurately reflect the current state of the sector.

4.6. Verification of the Validity of the Proposed Research Question

Based on the analysis of data obtained from the Czech Statistical Office and the Wine Fund, alongside professional publications and reports from the Czech Winegrowers Association on the state of Czech viticulture, as well as findings on wine production and consumption trends, the validity of the proposed research question has been confirmed.

The sustainable development of viticulture in Czechia depends primarily on the following:

The preservation—and potential expansion—of existing vineyard areas;

The promotion of wine tourism;

Targeted support for family-run wineries;

The sale of high-quality barrel wines through specialized wine shops;

The successful representation of Czech wines at international competitions.

The sustainable development of viticulture in Czechia may also be significantly influenced by the effects of ongoing climate change, primarily through a shift in vineyard composition favoring red grape varieties.

To support this transition, the following recommendations are proposed:

4.6.1. State-Level Recommendations

In Czechia, foreign wines dominate consumption, accounting for over 70% of total wine intake—largely due to their exemption from excise tax. To support domestic producers, particularly small-scale winemakers unable to compete with low-cost imports, it is advisable to consider introducing a tax on foreign wines. If taxed at the same rate currently applied to sparkling wine, the state budget could gain approximately two billion CZK annually;

Continue supporting the participation of Czech winemakers in prestigious international wine competitions through the Wine Fund and SZIF;

Promote the international success of Czech wines by co-financing advertising campaigns in foreign media. This initiative would underscore the rising quality of domestic production;

Enhance the international competitiveness of Czech wine and foster generational renewal in the sector by leveraging the Support Program in Viticulture;

One avenue for preserving and developing viticulture beyond Czechia’s two principal wine regions involves state support for historic urban vineyards.

4.6.2. Recommendations for Gastronomy Businesses

The art of pairing wine and food should no longer be confined to luxury dining establishments. It is increasingly essential for mid-range gastronomy businesses to master this skill;

In light of rising living standards, Czech consumers are placing greater emphasis on wine quality within gastronomy and demonstrating a willingness to pay premium prices. It is therefore essential for businesses to proactively adapt to this trend.

4.6.3. Recommendations for Winemakers and Winegrowers

For small and medium-sized winemakers, it is strategically advantageous to reduce reliance on low-margin retail chain sales and instead prioritize their own distribution channels—including direct-to-consumer sales, online shops, and delivery services;

For wineries focused on high-quality “terroir”-driven production, distribution through specialized wine shops is particularly advantageous. These outlets provide expert advice to consumers, enhancing the appreciation and informed selection of wines;

Support the placement of high-quality local wines—which appeal to Czech consumers and are competitively priced compared to foreign equivalents—on supermarket shelves. Moreover, these wines do not compete with low-cost imports. Moravian wines should be positioned within the middle and premium range, as Czech producers are unable to match the pricing of foreign wines in the lowest category.

4.6.4. Recommendations for Winemakers and Distributors

4.6.5. Recommendations for Consumers

Leverage wine tourism to boost domestic wine consumption;

Although the consumption of wines with higher residual sugar is relatively well-established in Czechia, current trends indicate a significant rise in the popularity of drier wines, which are generally more suitable for regular consumption due to their lower sugar content.

4.7. Limitations of the Research

This research article draws primarily on insights into the development of indicators measuring the economic performance of viticulture and wine production in Czechia, with the aim of evaluating their relevance to the sustainable development of the sector. It would be highly beneficial to examine the development of identical indicators in countries with comparable soil and climatic conditions—notably Germany and France, which share similar geographic characteristics with Czechia. This would allow for meaningful comparison and statistical validation of Czech viticulture’s standing.

5. Conclusions

Viticulture represents not only a cultural and social phenomenon, but also a sector of considerable economic significance. As such, it merits focused attention from the broader professional community. As demonstrated by the research in the analytical section, the claims made by cited experts in winemaking and viticulture accurately reflect the current state of the industry and are well founded.

The statistical analysis of Czech winemaking and viticulture data suggests that the sector is poised for steady and sustained growth in the coming years.

Grape growing and winemaking are among the key agricultural domains in Czechia and have undergone notable qualitative improvements in recent years. Wine producers from Moravia and Bohemia are fully competitive with leading European and global wines. A distinguishing feature of wines from these regions is their natural acidity [

39].

In Czechia, consumers frequently opt for imported wines—in two out of three cases, whether in specialty shops, retail chains, or restaurants. This preference is largely shaped by strong marketing, subsidized pricing, and deep-rooted perceptions of quality tied to traditional wine-producing countries. While premium foreign wines often justify their reputation, many lower-tier imports rely on branding and attributes that may reinforce misleading stereotypes about their superiority over domestic alternatives.

Wines from Czechia are distinguished by their high quality, varietal diversity, and strong reflection of local climatic and soil conditions. Each winemaker contributes a unique stylistic imprint. The above-average quality of Czech wines is consistently validated through regular successes at prestigious international competitions, where they often outperform products from traditionally dominant wine-producing countries.

The current economic and regulatory environment discourages many Czech winemakers from expanding or renewing vineyard areas, resulting in a gradual but undesirable decline in total vineyard acreage. In 2024, Czech winemakers failed to meet the permitted vineyard planting quota for the fifth year. Although the national quota allowed for the establishment of up to 178.3 hectares, only 84 applications were submitted, totaling a mere 40.5 hectares.