Abstract

The objective of this study was to assess the level of financial security of farms and identify its determinants based on factor analysis. The data used in this research were obtained from the European FADN (Farm Accountancy Data Network). Factor analysis (FA) was employed to reduce the number of variables that potentially determine the financial security of farms. The results indicate that the surveyed entities maintained financial security between 2014 and 2021. This study suggests that it is necessary to examine these factors separately for farms engaged in crop farming and animal production. The results obtained for all farms were less satisfactory than those that took into account the specifics of agricultural production. This study addresses a gap in the literature by including highly correlated variables in the analysis of the determinants of financial security. Factor analysis is used to reduce the number of variables without losing important information. Firstly, seventeen variables related to the financial security of all farms were assigned to six factors. These were income and self-financing of operations; area and subsidies; long-term investments and financial decisions consequences; economic size, taxes, and non-breeding livestocks; investment activity; and inputs, stock, short-term loans, and labor. Then, the determinants of the financial security of farms were examined, taking into account the specialization of activities. For crop-producing farms, six factors were identified, including three that were identical to those for all farms: income and self-financing of operations; long-term investment and financial decisions consequences; and investment activity. In addition, the following items were specified: area, subsidies, non-breeding livestocks, and taxes; economic size, inputs, and labor; and stock and short-term loans. The correlated variables in the case of livestock production combined into factors in a different way. In this case, four factors were distinguished: economic size, non-breeding livestocks, income, and self-financing of operations; operational activities of animal production; long-term investment and financial decisions consequences; and investment activity. Financial security is a complex matter that can be affected by a range of factors related to agricultural activities.

1. Introduction

Financial security can be understood as the state of financial resources that ensures the effective (profitable) operation of a given entity, secures its financial interests, provides its ability to maintain financial liquidity and solvency, and its financial capability in the face of various risks and threats []. The financial security of a farming enterprise refers to its ability to withstand events that disrupt or have the potential to disrupt its production activities and impede its growth []. In the literature, another approach equates financial security to a company’s capacity to maintain the ability to meet current obligations and operate efficiently []. Therefore, financial security is closely related to the level of financial liquidity and working (turnover) capital of a given entity [].

Financial security can be defined as the ongoing process of reducing and eliminating monetary risks to ensure capital adequacy according to the risk and preference profile of the subject []. The results of studies presented in the literature show that diversification of production, among other things, plays an important role in reducing the risk of agricultural activities and thus increasing the financial security of farms [,]. An essential concern within the discussed scope is the identification of factors affecting the financial security of farms, including those related to the financial resources of a particular entity. Accessing and mobilizing financial resources, i.e., access to capital, its cost, possibilities, and limitations in obtaining it, are vital parts of farm development at every stage []. Decisions made in this area inevitably influence the financial security of a given entity.

The study of Ryś-Jurek [] investigated the financial security of farms across four areas that were measured by five indicators. These areas included (1) property and capital relations, which were measured by the financial security indicator, (2) liquidity and debt, which were measured by the accelerated liquidity indicator and general debt ratio, (3) operational efficiency, which was measured by the asset coverage ratio with net working capital, and (4) financial efficiency, which was measured by the profitability ratio. The farms’ financial security ratio is presented in the following manner (Formula (1)) []:

where:

FS = GB + QR − DR + NWCTA + PEC

- FS—financial security ratio;

- GB—golden balance sheet rule (equity/fixed assets);

- QR—quick ratio (current assets − inventory − non-breeding livestock)/current liabilities);

- DR—total liabilities to total assets (total liabilities/total assets);

- NWCTA—coverage of assets by net working capital ((current assets − current liabilities)/total assets));

- PEC—profitability of equity capital (farm net income/equity).

A score < 0 indicates no financial security, [0.0–2.0) indicates a risk of losing financial security, [2.00–5.0) indicates financial security, [5.0–7.0] indicates high financial security, and a score >7.0 indicates above-threshold financial security.

The financial security level impacts the risk of bankruptcy for entities. Discriminatory models are commonly used to evaluate the financial condition of enterprises. E. Altman is a pioneer in this field and created widely used models for assessing the financial condition of enterprises, with a focus on the risk of collapse [,]. These models have been used for enterprises engaged in agricultural production []. However, there is a debate in the literature regarding the universality of the use of discriminatory models for enterprises with different business profiles, as well as those operating in different countries []. It is important to note that conducting research on agricultural farms has significant limitations due to data availability. Ryś-Jurek [] proposed a financial security index that considers both the areas frequently found in the literature affecting the financial security of farms and the financial categories created by the FADN system. The FADN system is the only system that collects data for EU farms according to uniform standards [].

Referring to the construction of the aforementioned indicators, financial security is linked to factors including the level and structure of assets, equity, and liabilities (including short-term ones), as well as the financial result (i.e., the level of farm net income).

The initial three factors specified pertain to the farm’s production capacity and funding sources. A characteristic feature of agricultural farms is their substantial self-financing and a comparatively minor proportion of debt in their financing source structure [,]. The research results affirm that farmers are characterized by a relatively high propensity to save, and they use the accumulated savings mainly to finance investments carried out on the farm []. On the one hand, a significant proportion of equity in the financing sources structure enhances the financial security of the entity, concerning aspects such as the golden rule of balancing, liquidity ratios, and profitability ratio. Therefore, it acts as the main source of financing to carry out all the processes related to agricultural activity []. On the other hand, debt can act as an additional source of financing, potentially impacting the investment behavior of farmers [,].

Regarding assets, these units mainly consist of fixed assets, with a particular emphasis on land that plays a significant role in agricultural activities []. Crop production and animal husbandry both require ownership of agricultural land, buildings, and structures for the storage and raising of produce and animals. In addition to land, farms’ production potential heavily relies on capital invested in other production assets, both fixed and current. The proper management of inventories, receivables, and liabilities is vital in increasing the financial security for a farm since it is interconnected with financial liquidity [].

In farming, where production is primarily supported by the work of household members and the assets of the farmer, determining the financial surplus—equivalent to net profit in enterprises—is challenging []. Farm net income serves as a measure of the financial outcome obtained from agricultural activity. The level of income, as demonstrated by the literature research findings, may be influenced by several factors. Important factors for a farm’s production potential (including land, machinery and equipment, and labor) and financing sources are crucial [,,,,]. The research results demonstrate that the impact of some factors can vary depending on the economic size of a farm [] and the direction of production [,]. Direct payments are a significant portion of farm income [,] and can shape the financial surplus from agricultural activities. Therefore, it is essential to consider the impact of direct support systems when studying farms located within the European Union. These systems represent a substantial source of funding for agricultural entities.

In studies of agricultural finance, a significant constraint is the strong correlation of potential variables []. Consequently, researchers often apply factor analysis, one of several methods used to analyze financial phenomena in farming []. This allows for the reduction in correlated variables without a significant loss of underlying information []. Taking into account the above, the aim of the study was to assess the level of financial security of farms and identify its determinants based on factor analysis. The study had three specific objectives assigned to it. (1) Assessing the financial security of an average EU farm from 2014 to 2021. (2) Identifying the determinants of financial security for all farms. (3) Identifying the determinants of financial security for farms, considering the specificity of their activities.

The implementation of specific research objectives contributes to the literature of financial security among EU farms. The first objective will analyze the level of financial security using Ryś-Jurek’s proposed indicator []. Objectives 2 and 3 provide an innovative approach and important research on the determinants of farms’ financial security. This study employs factor analysis to include variables that are highly correlated with each other. When assessing financial security, it is crucial to consider four key factors. Firstly, property and capital relations, which are measured by the financial security indicator. Secondly, liquidity and debt, which are measured by the accelerated liquidity indicator and general debt ratio. Thirdly, operational efficiency, which is measured by the asset coverage ratio with net working capital. Finally, financial efficiency, which is measured by the profitability ratio []. Factor analysis is used to reduce highly correlated variables without losing important values, which are crucial in assessing financial security.

The structure of this paper is as follows: Section 2 provides an outline of the research methodology and data sources. Section 3 presents the empirical research findings, which include an evaluation of the financial security of farms within the European Union (Section 3.1). The subsequent section examines the connections between the determinants of farms’ financial security using factor analysis (Section 3.2). The last two sections summarize the results and propose potential areas for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

The survey utilized information obtained from the FADN (Farm Accountancy Data Network) system to enable a comparison of agricultural operations in EU countries. The system covers farms that make an important contribution to the creation of added value in agriculture []. The data are collected and published according to consistent principles, with the sample selection process designed to ensure representativeness. The FADN system considers the selection of farms based on their economic size, agricultural type, and geographical location (individual EU countries and regions in member states). The provided data pertain to an average farm.

This study analyzed data extracted according to geographical location and agricultural type across the European Union and specific regions of EU countries. This study excluded data from Great Britain. The subjective scope is an average European Union farm and average farms separated in individual regions and according to individual agricultural types. To determine the agricultural type, the share of the value of Standard Production (SO) from different agricultural activity groups is calculated, and this value is divided by the total value of SO of the farm. This stratification into agricultural types enables the specificity of agricultural activity to be taken into account when assessing financial security. The FADN system recognizes the following agricultural types: Fieldcrops, Horticulture, Wine, Other permanent crops, Milk, Other grazing livestock, Granivores, and Mixed. The FADN system classifies farms by economic size. The research indicates that economic surpluses from farming activities depend on the economic size class achieved [,]. In future stages of this study, factor analysis will be applied to isolate the determinants of financial security of economically weak, medium, and strong farms. The current study includes the variable Size (SE005 Economic size; €’000), which reflects the economic size of farms (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Catalog of variables accepted for factor analysis with their description from the FADN system.

The period during which the financial security level of an average farm is evaluated spans from 2014 to 2021. To ascertain the factors that contribute to the financial security level of farms, information on regions and agricultural types identified during 2014, 2017, and 2020 was analyzed. The use of a three-year timeframe was intentional, as agriculture is known to be affected by high environmental risks that can lead to significant variations in prices and production values [].

This study consisted of three phases. Firstly, we assessed the level of financial stability of an average farm in the European Union, using the indicator proposed by Ryś-Jurek [] (Formula (1)).

The second stage of this study was to identify the links between the determinants of farms’ financial security. For this purpose, data on average farms of separate agricultural types in individual EU regions were obtained from the FADN system. A total of 2125 observations were considered. During this stage of the study, the variables potentially determining the financial security of the farms were reduced for all the surveyed units. In the third stage of this study, the specificity of the agricultural activity was taken into account in the assessment of financial security by grouping the types identified in the FADN system into two groups. The first is crop production (Fieldcrops, Horticulture, Wine, Other permanent crops). The second is animal production (Milk, Other grazing livestock, Granivores). The mixed type was not included in this study. The analysis included 990 observations for crop production and 835 for livestock production.

Factor analysis (FA) was used to reduce the number of variables potentially determining the financial security of farms. Factor analysis is a data reduction technique that entails creating a smaller number of new composite dimensions to represent the original variables instead of eliminating them []. The technique involves two main methods, principal component analysis (PCA) and factor analysis (FA) []. PCA replaces the original variables with an orthogonal set of their linear combinations (components) and arranges them based on their information content, from highest to lowest. The arrangement of components allows for preserving only a limited number of recently developed components while maintaining significant variation. FA suggests the existence of few latent variables, with each measured variable representing a portion of one or more of these factors.

The factor analysis model assumes that each of the observed variables Xi can be represented as a linear function of unobservable variables Fi (hypothetical variables obtained by analysis from a set of observed variables) and a single random factor Ui (specific factor) [,,]. The model can be written in scalar or matrix form, as shown in Formulas (2) [,] and (3) [].

where:

- k < p; Xi for i = 1, 2, …, p—real variables subject to observation;

- Fj for j = 1, 2, …, k—searched unobservable variables called common factors;

- aij for i = 1, 2, …., p and j = 1, 2, …, k—linear combination coefficients (factor loadings) of the j-th factor; Fj in the i-th observed variable Fj in the i-th observed variable Xi;

- Ui for i = 1, 2, …, p the i-th random factor, characteristic of the i-th variable.

The second way of writing the factor analysis model is shown in Formula (3) []:

where:

- X—vector of variables;

- A = (aij)—matrix of coefficients of linear combinations called factor loadings;

- F—vector of common factors;

- U—vector of specific factors;

- B—diagonal matrix of factor loadings of specific components.

The applicability of factor analysis is frequently assessed using Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity and/or the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure, which both rely on the correlation matrix [], while the results are considered robust to non-normality [,]. The results were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05. Analyses were performed using the statistical program R, ver. 4.3.0.

On the basis of the results presented in the literature and of the research carried out in previous periods [,,,,,,,], a catalog of variables shaping the financial security of farms in the European Union was indicated (Table 1). The variables were tested in the second and third stages of this study.

3. Empirical Results

3.1. Assessment of the Financial Security of Farms in the European Union

In the first stage of this study, the level of the financial security ratio of an average European Union farm in the years 2014–2021 was assessed. The Formula (1) proposed by Ryś-Jurek [] was used for the calculations. The obtained results, together with data characterizing an average farm in the European Union, are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Data required to calculate the financial security ratio, components of financial security ratio, and financial security ratio of an average farm in the European Union in 2014–2021.

According to the standards given in the literature [], the average EU farm was financially secure from 2014–2018. Since 2019, the indicator has increased and exceeded the level defined as high financial security. One of the reasons for this situation is the low tendency of farmers to take on debt []. This is due, among other things, to the characteristics of agriculture, which include, first and foremost, high capital intensity relative to the level of sales and guaranteed cash surplus; having mainly fixed assets in the asset structure, which are inflexible and closely tied to the unit; long production cycles; and limitations in raising capital in the securities market []. Throughout the period, equity capital accounted for approximately 83% of the sources of the financing structure. The share of current liabilities in total liabilities has remained relatively stable, ranging from 3.76% in 2014 to 4.20% in 2018, despite an increase in their overall value since 2019. At the same time, fixed assets dominate the structure of assets. However, their share of assets decreased from 81.43% at the beginning of the period to 74.96% at the end of the period. This was due to the fact that current assets grew faster than fixed assets, especially in times of economic uncertainty. This fact led to an increase in the quick ratio, which had the greatest impact from 2019–2021 on the increase in the value of the financial security ratio to the level known as high financial security.

3.2. Identifying Links between Factors That Determine the Financial Security of Farms

In the second stage of this study, the initially isolated variables shaping the financial security of farms (Table 1) were reduced for all the surveyed units by means of factor analysis. Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics of the variables for all farms, as well as for farms specializing in crop production and animal production.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of the variables.

According to the descriptive statistics, farms engaged in livestock production generate a higher economic surplus (income from the family farm). However, this requires them to invest in fixed assets of a higher value and incur higher capital expenditure. These farms exhibit a higher average value of short-term liabilities, which may negatively impact their financial security. However, they also demonstrate a higher average ability to self-finance their activities compared to farms engaged in crop production and all farms, without specialization. This is also linked to their larger average farm size, which affects the amount of operating subsidies received.

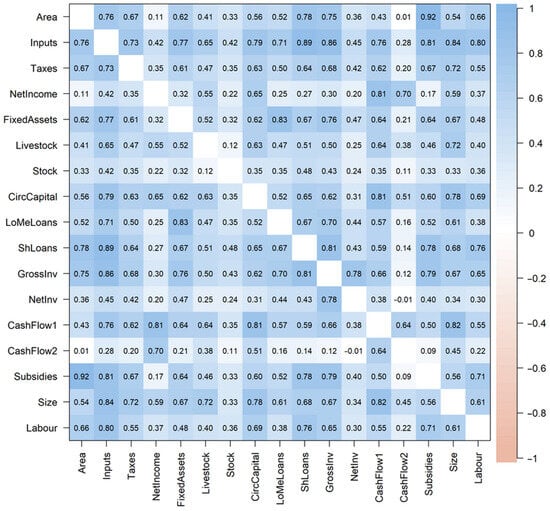

As might be expected, the variables that were selected for this study on the basis of substantive reasons are highly correlated with each other (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Correlation matrix. Source: own study based on EU FADN data [Agriculture–FADN: F. A. D. N.–FADN PUBLIC DATABASE (europa.eu), 1 April 2023].

The highest correlation coefficients were found between the variables Area and Subsidies (0.92), Inputs and ShLoans (0.89), and Inputs and GrossInv (0.86). The correlation between the selected variables results, among other things, from the specificity of agricultural production. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin test revealed that the sampling adequacy (SMA) to factorability is 0.88 for all types of farms, 0.83 for “Crops”, and 0.88 for “Livestock”; the individual SMAs are in Table 4. Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity also stated the applicability of factor analysis ( in all 3 cases).

Table 4.

The measure of sampling adequacy for each variable (Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin test).

This study used a non-orthogonal oblimin rotation [] because most of the variables considered are related in one way or another to the scale of farms in a given region, making the assumption of factor orthogonality unjustified.

In the further part of this study, factor analysis was used to reduce the correlated variables to a smaller number of factors without a significant loss of information on financial security for all EU farms. Parallel analysis suggested six factors. The loadings of variables with values above 0.1 in individual factors are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Factor loadings of variables, all types of farms.

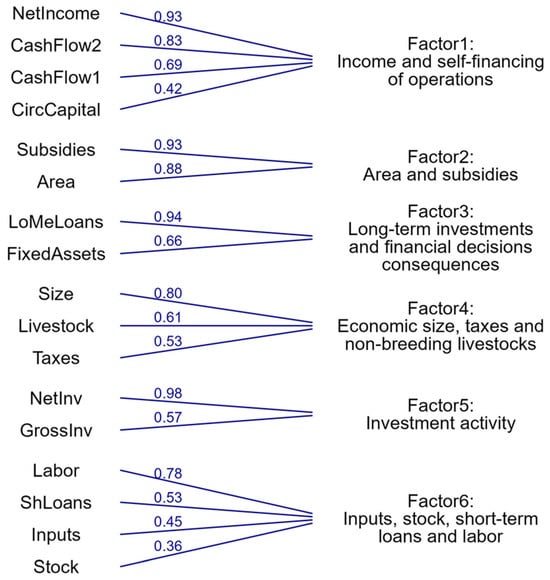

Factor 1 includes the variables NetIncome (highest loading in this factor), CircCapital, CashFlow1, and CashFlow2. Factor 2 includes the variables Area, Subsidies; Factor 3—FixedAssets and LoMeLoans. Factor 4 includes Taxes, Livestock, Size, while factor 5 includes GrossInv and NetInv. Factor 6 includes Inputs, Stock, ShLoans, and Labor. The factors obtained were given the names shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Assignment of variables to factors and appropriate loadings, all types of farms. Source: own study based on EU FADN data [Agriculture–FADN: F. A. D. N.–FADN PUBLIC DATABASE (europa.eu), 1 April 2023].

From seventeen isolated variables shaping the financial security of farms from regions of EU countries, six synthetic factors were obtained through factor analysis. Factor 1, which explains most of the phenomena studied, is income and self-financing of operations. This factor thus provides an inflow of financial resources. The level of financial security of farms depends on the high share of internal sources in the process of financing operations. The second factor is area and subsidies. On the one hand, land is the basic factor of production in agriculture, but on the other hand, due to legal regulations, it also largely determines the amount of subsidies that farms receive. The third factor reflects the long-term investments and financial decisions consequences. The financial resources acquired by the farm over a long period of time (long-term liabilities) are generally allocated to investment in fixed assets. The high share of fixed assets in the asset structure and the high involvement of constant capital (equity plus long-term liabilities) have a positive impact on the level of financial security. Investment activity is also reflected in the fifth factor, which reflects the value of investments. The remaining two factors reflect the operational activities of the farms. These are economic size, taxes, and non-breeding livestocks, and inputs, stock, short-term loans, and labor. On the one hand, short-term liabilities reduce financial liquidity, which is crucial for the level of financial security. On the other hand, factor analysis makes it possible to use the information contained in them in combination with other variables. It can be concluded that capital from short-term external financing sources leads to increased production, which in turn leads to increased costs, employment, and the value of stock. Therefore, the impact on financial security can be positive. The cumulative variance index for the extracted factors is 0.60, which is an acceptable level in the social sciences [].

In the final stage of this study, the specificity of agricultural activity was taken into account in the study of factors determining the financial security of farms in EU regions. Firstly, data on farms engaged in crop production were examined. A parallel analysis suggested six factors. The loadings of variables with values above 0.1 in individual factors are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Factor loadings of variables, crop production (Crops).

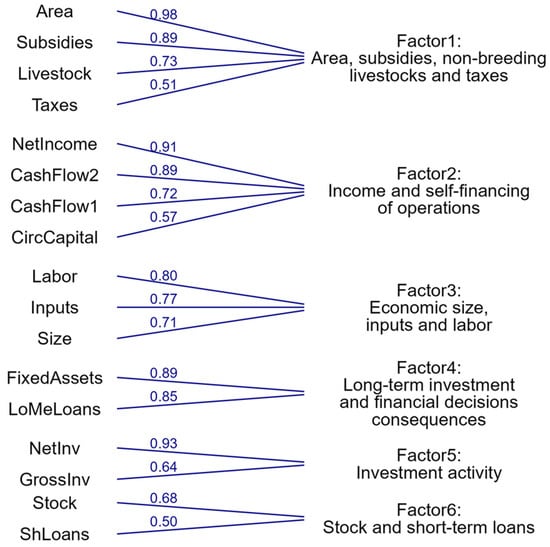

Factor 1 includes the variables Area, Taxes, Livestock, and Subsidies; factor 2—NetIncome, CircCapital, CashFlow1, and CashFlow2. Factor 3 includes Inputs, Size, and Labor. Factor 4 included FixedAssets and LoMeLoans; in factor 5—GrossInv and NetInv. In factor 6—Stock and ShLoans. The meaning of the factors is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Assignment of variables to factors and appropriate loadings, crop production (Crops). Source: own study based on EU FADN data [Agriculture–FADN: F. A. D. N.–FADN PUBLIC DATABASE (europa.eu), 1 April 2023].

In the case of farms specializing in crop production, the first factor is area, subsidies, non-breeding livestocks, and taxes. Sources of financing for large farms are among other subsidies for operating activities, including subsidies directly related to the number of hectares of land they own. This factor may also be crucial for maintaining financial security. It should also be noted that this factor includes a variable: Livestock. Despite their chosen specialization, farms very often diversify their activities in order to reduce the operational risk. It is likely that the liquidation of the non-breeding livestock provides an additional source of capital for farms specializing in crop production, which is used to improve current financial liquidity. Factors 2, 4, and 5 contain exactly the same variables as for all farms. Factor 3 is economic size, inputs, and labor, and factor 6 is stocks and short-term loans. Both factors are related to operating activities. The cumulative variance index of the results of the factor analysis carried out for the farms specializing in crop production is 0.67, which is higher than that obtained for all farms.

In the case of farms with animal production, the parallel analysis suggested four factors. This may indicate that the group of farms with animal production are more homogeneous, as the number of factors for all farms and for animal production was six. Loadings of variables with values above 0.1 in individual factors are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Factor loadings of variables, animal production (Livestock).

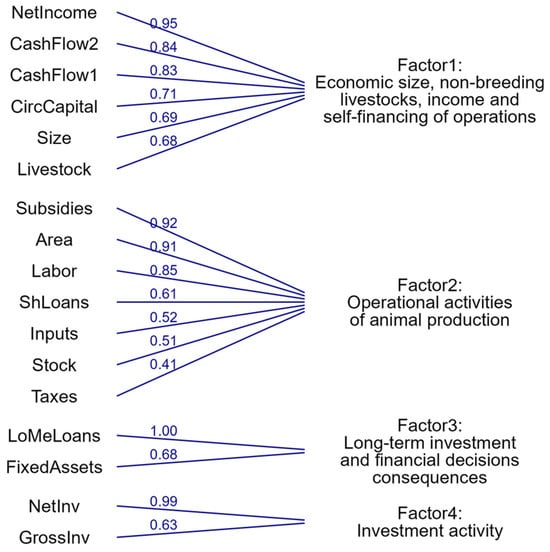

The following variables were qualified for factor 1: NetIncome, Livestock, CircCapital, CashFlow1, CashFlow2, and Size. Factor 2 includes Area, Inputs, Taxes, Stock, ShLoans, Subsidies, and Labor. Factor 3 includes FixedAssets and LoMeLoans; and in factor 4—GrossInv and NetInv. The factors obtained were given the names shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Assignment of variables to factors and appropriate loadings, animal production (Livestock). Source: own study based on EU FADN data [Agriculture–FADN: F. A. D. N.–FADN PUBLIC DATABASE (europa.eu), 1 April 2023].

The first factor is economic size, non-breeding livestocks, income, and self-financing of operations. This factor mainly includes variables that represent access to financial resources. The highest value of the load was obtained by the farm net income and cash flows, which shows the ability to self-finance. Therefore, as in the case of all farms, if a farm generates financial resources in the form of equity, it is financially secure. The second factor reflects the operational activities of animal production. The variables include Subsidies and ShLoans, which also generate financial resources, which should have a positive effect on the level of financial security, although short-term liabilities themselves reduce financial liquidity. As for all farms and farms specializing in crop production, the last two factors are the long-term investment and financial decisions consequences and investment activity. The cumulative variance index is 0.67. It is therefore at the same level as for animal production. The research carried out has therefore shown that it is justified to take account of the specific nature of agricultural activity when studying the financial security of these units.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to assess the level of financial security of farms and identify its determinants based on factor analysis. The research was carried out on European Union farms that participated in the FADN (Farm Accountancy Data Network) system. Initially, the financial security level of EU farms was evaluated. The obtained findings align with the previous literature [,,]. The research findings demonstrate that the entities under survey demonstrated financial security from 2014–2021. This was primarily due to the conditions of operation of farms. Our results indicate that these entities have a strong inclination for self-funding their activities [], financing both operational and investment activities primarily from equity capital, significantly limiting the inflow of financial resources in the form of external capital, especially short-term liabilities. Thus, maintaining high financial liquidity is a key aspect of financial security. Additionally, due to the crucial role of farms in the food supply chain and the need to ensure its sustainability, institutional support is provided in the form of subsidies for operating activities, which serve as a source of financing for these entities. Subsidies form a substantial portion of farm income [,] and have a significant impact on financial security. During the second and third stages of this study, factor analysis was employed to reduce the variables that could potentially impact the financial stability of farms in the European Union. As a result of this study, it was concluded that factor analysis can be effectively utilized to evaluate factors that contribute to farms’ financial security. It is important to acknowledge the high correlation among certain variables in research on farms’ finances, which serves as an important limitation []. Factor analysis is one of the methods used to analyze financial phenomena in agriculture [], which reduces the number of correlated variables without a significant information loss []. Firstly, seventeen variables related to the financial security of all farms were assigned to six factors. These were income and self-financing of operations; area and subsidies; long-term investments and financial decisions consequences; economic size, taxes, and non-breeding livestocks; investment activity; and inputs, stock, short-term loans, and labor. Then, the determinants of the financial security of farms were examined, taking into account the specialization of activities.

For crop-producing farms, six factors were identified, including three that were identical to those for all farms: income and self-financing of operations; long-term investment and financial decisions consequences; and investment activity. In addition, the following items were specified: area, subsidies, non-breeding livestocks, and taxes; economic size, inputs, and labor; and stock and short-term loans. The correlated variables in the case of livestock production combined into factors in a different way. In this case, four factors were distinguished: economic size, non-breeding livestocks, income, and self-financing of operations; operational activities of animal production; long-term investment and financial decisions consequences; and investment activity. Analyses carried out considering the orientation of farm activities were more satisfactory than those conducted for all farms. This finding confirms the need to consider the specificity of agricultural activity when conducting research on the financial security of farms.

In conclusion, it can be stated that studying the financial security of all farms is not crucial in determining the factors that influence it. The results obtained for all farms were less satisfactory than those that took into account the specifics of agricultural production. For farms that specialize in crop production, six factors were identified, with land and operating subsidies being key. Land is the foundation for crop production, and the value of subsidies received depends primarily on the farmland area. The inclusion of rotating stock in factor 1 may seem surprising, but it may be due to the unique nature of crop production. The land available to farms includes farmland that is used directly for the production of grains, vegetables, fruits, or other crops. However, farms often have meadows and pastures that can be used for grazing livestock. In addition, crop production is more seasonal than livestock production. Thus, vegetable farms diversify their production, which can affect their financial security. For farms specializing in livestock production, only four factors were identified as potentially determining financial security. This may indicate that this group of farms are more homogeneous. It is necessary to take into account the specificities of agricultural activities in the research on the determinants of agricultural holdings.

5. Conclusions

The research findings contribute to both the literature and practice. Regarding the first aspect, the results obtained constitute a thread in the discussion on factors affecting the financial security of farms. This underscores the importance of the careful consideration of financial factors for sustainable farming. The findings of this study indicate the need to investigate these factors separately for farms engaged in crop farming and animal production. It has been shown that financial resources play a significant role in determining the financial security of European Union farms. In particular, the advantages of using factor analysis to assess the financial security of farms should be emphasized. Previous studies lacked the application of this method, resulting in a reduction in variables in the modeling and a loss of relevant information []. Financial security is a complex phenomenon, as evidenced by the number of areas considered in its measurement. Factor analysis enables the inclusion of highly correlated variables in further modeling.

Thus, the results of our study can act as an informative source for institutions concerned with the financial safety of farms, which form a crucial element in the food supply chain, and the preservation of their financial security is vital to guarantee its continuity. Furthermore, given the tight linkages between the farm and the farmer’s household [], ensuring the financial security of these entities is of utmost significance.

The obtained results contribute to determining the direction of further research, which will include, among others, examining the strength and direction of the influence of isolated factors on the level of financial security of farms focused on plant and animal production. Due to the specific nature of the activities of agricultural entities, the variables describing financial security are correlated, which makes it difficult to test them in order to determine their impact on the level of financial security. Factor analysis allowed for the reduction in these variables into specific groups (factors) without a significant loss of the information contained in them. The next stage of research will therefore include assessing the strength and direction of their impact on financial security. Moreover, it is also planned to take into account economic size in research on the financial security of farms. Previous studies have shown that farms using external capital [,] have higher levels of investment activity. These farms generally achieve a higher economic size. In further stages of research, it is necessary to verify the importance of an increase in economic size for the level of financial security. However, the conducted research has a significant limitation due to the difficult access to individual data characterizing farms from individual countries. Additionally, the data collected in the FADN system are published with a delay, making it difficult to analyze the impact of the current economic situation on the financial security level of farms. Future research plans to use individual data obtained during a survey among farms participating in the FADN system, which will constitute the next stage of the research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.S.-S., A.S., R.A. and D.Z.; methodology, E.S.-S., A.S., R.A. and D.Z.; software, E.S.-S., A.S., R.A. and D.Z.; validation E.S.-S., A.S., R.A. and D.Z.; formal analysis, E.S.-S., A.S., R.A. and D.Z.; investigation, E.S.-S., A.S., R.A. and D.Z.; resources, E.S.-S., A.S., R.A. and D.Z.; data curation, E.S.-S., A.S., R.A. and D.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, E.S.-S., A.S., R.A. and D.Z.; writing—review and editing, E.S.-S., A.S., R.A. and D.Z.; visualization, E.S.-S., A.S., R.A. and D.Z.; supervision, E.S.-S., A.S., R.A. and D.Z.; project administration, E.S.-S., A.S., R.A. and D.Z.; funding acquisition, E.S.-S., A.S., R.A. and D.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was carried out as part of the research project entitled: Sustainable investing on agricultural markets in the context of a potential food crisis, financed as part of statutory research of the Koszalin University of Technology.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article. These data can be found here: [Agriculture–FADN: F. A. D. N.–FADN PUBLIC DATABASE (europa.eu); https://agridata.ec.europa.eu/extensions/FADNPublicDatabase/FADNPublicDatabase.html accessed on 1 April 2023].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Delas, V.; Nosova, E.; Yafinovych, O. Financial Security of Enterprises. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 27, 248–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ryś-Jurek, R. Bezpieczeństwo Finansowe i Stabilność Finansowa Gospodarstw Rolnych w Polsce po Akcesji do Unii Europejskiej; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego w Poznaniu: Poznań, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franc-Dąbrowska, J. The financial security versus effectiveness of equity involved (Bezpieczeństwo finansowe a efektywność zaangażowania kapitałów własnych). Rocz. Nauk Rol. SERIA G 2006, 93, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimon, G.; Tarighi, H.; Salehi, M.; Sadowski, A. Assessment of Financial Security of SMEs Operating in the Renewable Energy Industry during COVID-19 Pandemic. Energies 2022, 15, 9627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bereżnicka, J. Financial Security of Farms in Selected European Union Countries in The Context of Environmental Protection Requirements. Ann. Pol. Assoc. Agric. Econ. Agribus. 2020, 2, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurdyś-Kujawska, A. Significance of production diversification in ensuring financial security of farms in Poland. J. Agribus. Rural Dev. 2016, 2, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurdyś-Kujawska, A.; Strzelecka, A.; Zawadzka, D. The Impact of Crop Diversification on the Economic Efficiency of Small Farms in Poland. Agriculture 2021, 11, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawadzka, D.; Strzelecka, A.; Szafraniec-Siluta, E. Debt as a Source of Financial Energy of the Farm—What Causes the Use of External Capital in Financing Agricultural Activity? A Model Approach. Energies 2021, 14, 4124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, E.I. Financial ratios, discriminant analysis and the prediction of corporate bankruptcy. J. Financ. 1968, 23, 589–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, E.I.; Hotchkiss, E.; Wang, W. Corporate Financial Distress, Restructuring, and Bankruptcy: Analyze Leveraged Finance, Distressed Debt, and Bankruptcy; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kiaupaite-Grushniene, V. Altman Z-score model for bankruptcy forecasting of the listed Lithuanian agricultural companies. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Accounting, Auditing, and Taxation (ICAAT 2016), Tallinn, Estonia, 8–9 December 2016; pp. 222–234. [Google Scholar]

- Iwanowicz, T. Empiryczna weryfikacja hipotezy o przenośności modelu Altmana na warunki polskiej gospodarki oraz uniwersalności sektorowej modeli. Zesz. Teoretyczne Rachun. 2018, 96, 63–80. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission, Agriculture and Rural Development. Available online: https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/data-and-analysis/farm-structures-and-economics/fadn_en (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Vučković, B.; Veselinović, B.; Drobnjaković, M. Financing of permanent working capital in agriculture. Econ. Agric. 2017, 64, 1065–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokop, M.; Vrabelova, T.; Novakowa, M.; Simova, T. Evaluation of Managerial and Decision-Making Skills of Small-Scale Farmers. In Proceedings of the 28th International Scientific Conference Agrarian Perspectives XXVIII, Business Scale in Relation to Economics, Prague, Czech Republic, 18–19 September 2019; pp. 218–225. [Google Scholar]

- Strzelecka, A. Determinanty Oszczędności Rolniczych Gospodarstw Domowych (Determinants of Farm Households Savings); Wydawnictwo Uczelniane Politechniki Koszalińskiej: Koszalin, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Szafraniec-Siluta, E.; Zawadzka, D.; Strzelecka, A. Application of the logistic regression model to assess the likelihood of making tangible investments by agricultural enterprises. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 207, 3894–3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrick, M. Farm Investment, Credit Rationing, and Governmentally Promoted Credit Access in Poland: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Food Policy 2004, 29, 275–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echevarria, C. A Three-Factor Agricultural Production Function: The Case of Canada. Int. Econ. J. 1998, 12, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimon, G.; Sobolewski, M.; Lew, G. An Influence of Group Purchasing Organizations on Financial Security of SMEs Operating in the Renewable Energy Sector—Case for Poland. Energies 2020, 13, 2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawadzka, D.; Strzelecka, A. Efektywność finansowa ekologicznych gospodarstw rolnych—ujęcie porównawcze z uwzględnieniem kierunku produkcji. In Finansowanie i Standing Finansowy—Wybrane Zagadnienia; Bereżnicka., J., Wasilewski, M., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Szkoły Głównej Gospodarstwa Wiejskiego w Warszawie: Warszawa, Poland, 2020; pp. 159–172. [Google Scholar]

- Carls, E.; Ibendahl, G.; Griffin, T.; Yeager, E. Factors Affecting Net Farm Income for Row Crop Production in Kansas. Am. Soc. Farm Manag. Rural Apprais. 2019, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gummi, U.M.; Mu’azu, A. Effect of Monetary and Non-monetary Factors on Rural Farmers’ Income in Wamakko Lga, Sokoto-Nigeria. Asian J. Rural Dev. 2019, 9, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocsis, J.; Major, K.A. General Overview of Agriculture and Profitability in Agricultural Enterprises in Central Europe. In Managing Agricultural Enterprises; Bryła, P., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Średzińska, J. Determinants of the income of farms in EU countries. Stud. Oeconomica Posnaniensia 2018, 6, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckman, J.; Schimmelpfennig, D. Determinants of farm income. Agric. Financ. Rev. 2015, 75, 385–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strzelecka, A.; Zawadzka, D.; Kurdyś-Kujawska, A. Factors Affecting Incomes of Small Agricultural Holdings in Poland. In Proceedings of the 28th International Scientific Conference Agrarian Perspectives XXVIII, Business Scale in Relation to Economics, Prague, Czech Republic, 18–19 September 2019; pp. 289–295. [Google Scholar]

- Strzelecka, A.; Zawadzka, D. Does Production Specialization Have an Impact on the Financial Efficiency of Very Small Farms? In Proceedings of the 36th International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA), Granada, Spain, 4–5 November 2020; pp. 573–584, ISBN 978-0-9998551-5-7. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D.; Liu, Z. Does farmer economic organization and agricultural specialization improve rural income? Evidence from China. Econ. Model. 2012, 29, 990–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stępień, S.; Guth, M.; Smędzik-Ambroży, K. Rola wspólnej polityki rolnej w kreowaniu dochodów gospodarstw rolnych w Unii Europejskiej w kontekście zrównoważenia ekonomiczno-społecznego (The Role of the Common Agricultural Policy in Creating Agricultural Incomes in the European Union in the Context of Socio-Economic Sustainability). Zesz. Nauk. Szkoły Głównej Gospod. Wiej. W Warszawie. Probl. Rol. Swiat. (Probl. World Agric.) 2018, 18, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ściubeł, A. Produktywność czynników produkcji w rolnictwie Polski i w wybranych krajach Unii Europejskiej z uwzględnieniem płatności Wspólnej Polityki Rolnej (Productivity of production factors in Polish agriculture and in the selected European Union countries with regard to the Common Agricultural Policy payments). Zagadnienia Ekon. Rolnej (Probl. Agric. Econ.) 2021, 1, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szafraniec-Siluta, E.; Strzelecka, A.; Ardan, R.; Zawadzka, D. Application of factor analysis to reduce the dimensionality of the determinants of equity capital return on European Union farms. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2023, 225C, 4432–4441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rikkonen, P.; Makijarvi, E.; Ylatalo, M. Defining foresight activities and future strategies in farm management: Empirical results from Finnish FADN farms. Int. J. Agric. Manag. 2013, 3, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Stanisz, A. Przystępny kurs Statystyki z Zastosowaniem STATISTICA PL na Przykładach z Medycyny. Tom 3. Analizy Wielowymiarowe; Statsoft: Kraków, Poland, 2007; pp. 213–268. [Google Scholar]

- Ryś-Jurek, R. Family farm income and their production and economic determinants according to the economic size in the EU countries in 2004–2015. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference Economic Sciences for Agribusiness and Rural Economy, Warsaw, Poland, 7–8 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kusz, B.; Kusz, D.; Bąk, I.; Oesterreich, M.; Wicki, L.; Zimon, G. Selected Economic Determinants of Labor Profitability in Family Farms in Poland in Relation to Economic Size. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Średzińska, J.; Standar, A. Wykorzystanie analizy czynnikowej do badania determinant dochodów gospodarstw rolnych (na przykładzie krajów Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej) (The use of factor analysis to study the determinants of farms’ income (on the example of Central and Eastern Europe countries)). Zesz. Nauk. Szkoły Głównej Gospod. Wiej. W Warszawie Ekon. Organ. Gospod. Żywnościowej 2017, 118, 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Jiawei, H.; Kamber, M.; Pei, J. Data Mining. Concepts and Techniques, 3rd ed.; Morgan Kaufmann: Hawthorne, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Desiderio, S. Factor analysis with a single common factor. MPRA Pap. 2018, 90426. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/90426/ (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Czopek, A. Analiza porównawcza efektywności metod redukcji zmiennych—Analiza składowych głównych i analiza czynnikowa (Comparative Analysis of Effectiveness of The Methods for Reduction of Variables—Principal Component Analysis and Factor Analysis). Stud. Ekon. 2013, 132, 7–23. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha, N. Factor Analysis as a Tool for Survey Analysis. Am. J. Appl. Math. Stat. 2021, 9, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, P.J.; West, S.G.; Finch, J.F. The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in con-firmatory factor analysis. Psychol. Methods 1996, 1, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, A.B.; Osborne, J.W. Best Practices in Exploratory Factor Analysis: Four Recommendations for Getting the Most From Your Analysis. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2005, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Bereżnicka, J.; Franc-Dąbrowska, J. Sources and Determinants of Cash Holdings in The Agriculture of Central and Eastern Europe Countries and The Perspective of The Financial Security of Polish Farms. Zesz. Nauk. SGGW Polityki Eur. Finans. Mark. 2022, 28, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliwoda, M. Bezpieczeństwo finansowe gospodarstw rolniczych w Polsce z perspektywy Wspólnej Polityki Rolnej (The Financial Security of Farms in Poland From a Perspective of the Common Agricultural Policy). Wieś I Rol. 2014, 3, 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Szafraniec-Siluta, E. Bezpieczeństwo finansowe przedsiębiorstw rolniczych w Polsce—Ujęcie porównawcze (Financial Safety of Agricultural Companies in Poland—Comparable presentation). Zarz. Finans. 2013, 11, 405–416. [Google Scholar]

- Bierlen, R.; Barry, P.J.; Dixon, B.L.; Ahrendsen, B.L. Credit Constraints, Farm Characteristics and the Arm Economy: Differential Impacts on Feeder Cattle and Beef Cow Inventories. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1998, 80, 708–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J.E. Oblimin Rotation; Wiley online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.S.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Franc-Dąbrowska, J.; Mądra-Sawicka, M.; Bereżnicka, J. Cost of Agricultural Business Equity Capital—A Theoretical and Empirical Study for Poland. Economies 2018, 6, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strzelecka, A.; Zawadzka, D. Savings as a Source of Financial Energy on the Farm—What Determines the Accumulation of Savings by Agricultural Households? Model Approach. Energies 2023, 16, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinych, N.; Odening, M. Capital Market Imperfections in Economic Transition: Empirical Evidence From Ukrainian Agriculture. Agric. Econ. 2009, 40, 677–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).