Abstract

Although the literature concerning poverty is rich in theory and policy suggestion, the implementation of poverty alleviation is still poorly studied. This study aims to answer the question of what could be considered a good framework for poverty alleviation and how to implement it in rural areas. Based on China’s experience, we here conceptualize an implementation framework and process by using a systemic approach. A five-year case study of over fourteen thousand poor households is used to demonstrate the effectiveness of the framework and process. The case study results show that poverty alleviation measures have been successfully implemented following the framework and process, and the absolute poverty is eliminated. Key characteristics of China’s poverty alleviation program, such as people-centered philosophy, pro-poor development, functional institution, systematic anti-poverty measures, and social mobilization may be useful for other poverty alleviation implementation approaches. The novel implementation framework and process, and pro-poor development strategy in this study can provide valuable experience for other poverty alleviation programs, and more similar poverty alleviation programs would make a significant contribution to the shared Sustainable Development Goals.

1. Introduction

In 2015, the United Nations adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and established 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including the first and second goal to eradicate extreme poverty and hunger for all people [1]. However, as of today, we are far from reaching the SDGs as global poverty and hunger prevail [2]. The World Bank reports that there were 689 million people living in extreme poverty in 2017, and the COVID-19 pandemic may have further pushed about 150 million people into extreme poverty between 2020 and 2021 [3]. Therefore, alleviating extreme poverty is an urgent and necessary task for the world.

The reasons behind poverty vary: physical geography, fiscal traps, governance failures, cultural barriers, geopolitics, demographic traps, and lack of innovation. All of these reasons can cause poverty [4]. As for some developed countries, inequality has been widening sharply due to a disproportionate share of economic gains for the rich; an ill tax system that favors the rich; the failure of governance, such as deregulation and the “too-big-to-fall” problem; and other structural failings of society [5,6]; thus, many people are trapped in poverty. Moreover, many developing countries face political instability, lack of investment, harsh living conditions, high unemployment, cultural populism, unequal asset distribution, and truncated agrarian transition [7,8,9,10]. Therefore, chronic poverty is always present in these developing countries, as is in some parts of China.

To counter extreme poverty, economic development is the predominate approach [11], while other policies, such as improving education and healthcare, are unvarying [12]. However, transforming theory into real-world action is not easy. Due to the complexity of poverty, some researchers explore concepts such as “resilience thinking” to help empower the poor and bring them out of poverty [13,14,15]; others conducted social experiments to fully understand how the poor live their lives, what they think, what they really need, and where interventions can be implemented [16]; and others improve assessment methods—from monetary poverty line or poverty gap to multidimensional poverty index—to better evaluate the poor’s conditions [17]. In terms of poverty interventions for the “Global South”, Sachs (2005) [4] calls for more international aids to invest in education, health care, and infrastructure. Other interventions, such as micro-finance [18], cash transfer and social safety nets [19,20], education system improvements [12,21], the integration of agriculture and industry [10], land consolidation [22], agro-ecological development [23], and green energy development [24] are also promoted.

Since the foundation of the People’s Republic of China, poverty alleviation has been an important issue, as China was one of the poorest countries in the world due to destruction from long periods of war. From 1949 to 1986, poverty alleviation programs mainly worked through government relief and structural reform, i.e., the distribution of agricultural land to each household [25,26]. In 1986, a new institutionalized system—the Leading Group Offices of Poverty Alleviation and Development (LGOP) or fupinban—was created at central, provincial, prefectural, and county government levels to oversee poverty issues. Poverty alleviation policies were shifted from an assistance-oriented to a development-oriented approach [27]. Under the theory of development-oriented poverty alleviation, a new strategy called “Targeted Poverty Alleviation” was introduced in 2013 to accurately identify poor individuals and households, create anti-poverty measures, manage resources, and evaluate impact [25]. Some detailed anti-poverty measurements are demonstrated by previous studies. For example, land consolidation has supported rural development by increasing cultivated land area, improving rural production conditions, and alleviating ecological risks [22]; resettlement is used as a tool for poverty alleviation in China, especially for those who live in dispersed and remote villages [28]; health projects (medical insurance/aid/subsidy) have reduced patient payments and decreased the likelihood of trapping in poverty [29]. A case study of Fuping County in China has also provided practice details of “Targeted Poverty Alleviation” [25]. China had tremendous success in poverty alleviation by reducing the population in extreme poverty from 165.7 million in 2010 down to 5.5 million in 2019, contributing to about 35% of the world’s poor population reduction in these years [30,31]. However, impoverished counties still persist and are unequally distributed: most are in western China, while some are in central China due to the “island-effect” [32]. Similar to islands in oceans, these impoverished counties are isolated in mountainous areas. Moreover, systemic frameworks that holistically aggregate all aspects and help tackle poverty implementation are lacking.

To successfully implement a development-oriented poverty alleviation program, two questions need to be answered: Firstly, what is a systemic framework for implementing a poverty alleviation program and secondly, how to implement it involving all actors? Although poverty literature is rich in theories, policy suggestions, and assessment methods, actionable implementation experience is still rare, especially within a systematic framework. Therefore, this study aims to provide an implementation framework and a process generated from China’s poverty alleviation experience to help others implement their own poverty alleviation programs. We first conceptualize the poverty implementation framework and describes the implementation process through systematic method. Official datasets from Jinggu County (a county in Yunnan Province, Southwest China) of over fourteen thousand poor households (over fifty thousand individuals) was then used to demonstrate the process of how to conduct poverty alleviation using this framework. Finally, this paper discusses the characteristics of China’s poverty alleviation experience, such as people-centered philosophy and pro-poor development and provides suggestions for other poverty alleviation programs. Although different countries may have different poverty alleviation strategies, the implementation framework, process, and pro-poor development strategy in this study can provide valuable experience for other poverty programs and consequently achieve the shared SDGs.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Poverty Implementation Framework

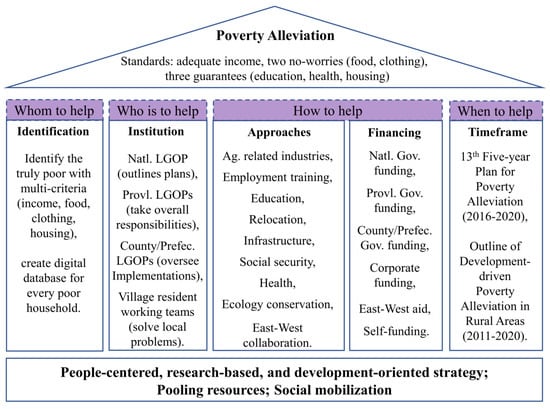

To eradicate extreme poverty effectively, several questions needed to be answered: whom to help, who should help, how to help, and when to help? Thus, we used a systemic approach, which holistically analyzed all participants and actors in the poverty alleviation program to gain a better understanding of poverty situations and the alternatives [33,34]. Figure 1 presents our framework for the implementation in China’s poverty alleviation program. Besides the conventional income standard, down-to-earth standards were set as the “two no-worries” and the “three guarantees”, which translate into no worries about food and clothing with a guarantee of education, health, and housing. Poor households were identified by their income and other basic needs, such as food (whether they stored enough food or their income could afford to buy enough food), clothing (whether they had adequate clothes already or their income could afford to buy clothes), education (whether nine-year compulsory education was guaranteed), health (whether health insurance covered all family members and whether any member was in serious illness), and housing (whether houses were safe). The identification of poor households involved a mixed top-down and bottom-up process; officials set up criteria and verified applications through a top-down process, while households filed application and discussed who were qualified through a bottom-up process (see details in Section 3.1). At the same time, information about their assets and the cause of their poverty was collected for further analysis and to find appropriate poverty alleviation measures. A unique file was created for each poor household and its members and then uploaded to an online information system for analysis and tracking throughout the whole anti-poverty process [35]. Together with local villagers, the identification process was conducted by village resident working teams, who were professionals dispatched by county-level or higher-level governments directly. County or prefecture LGOPs were overseeing the implementations of poverty eradication, provincial LGOPs took full responsibility to localize the plan in their governing areas, and the national LGOP was responsible for overall planning. Generally, there were nine approaches to reducing poverty: developing agriculture and related industries; employment training; providing free universal basic education and subsidizing higher education; relocating villagers from arduous and vulnerable areas; upgrading infrastructure, such as roads and telecommunication; providing universal social security and welfare; providing basic health care; compensating for ecological conservation services; and encouraging collaboration between eastern and western provinces. Different financial sources were raised to support poverty alleviation, including government funding, corporate funding, eastern provinces’ aid, and farmer or local entity self-funding. Moreover, the timeframe of poverty alleviation was clearly defined by two plans: “the 13th five-year plan for poverty alleviation (2016–2020)” and the “outline of development-driven poverty alleviation in rural areas (2011–2020)” [36,37]. Overall, poverty alleviation programs were people-centered, research-based, and development-oriented.

Figure 1.

The framework of China’s poverty alleviation implementation. LGOP = Leading Group Offices of Poverty Alleviation and Development; Natl. = national; Provl. = provincial; Prefec. = prefecture; Ag. = agriculture; and Gov. = government.

2.2. The Case Study Area and Data

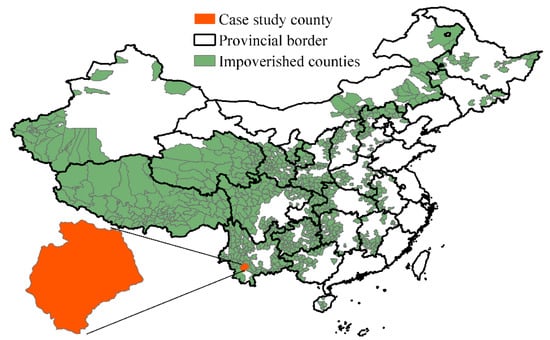

Located in Yunnan Province in southwest China, Jinggu County is one of the poorest of the 832 counties in China (Figure 2). In 2020, about 320,000 people, belonging to 26 different ethnic groups, were living in Jinggu County. Most of its 7777 km2 land area is mountainous, which makes it hard to access and develop agriculture. Villages are scattered in the valleys between high mountains and small towns and provide only basic services for nearby residents. The Gross Domestic Production per capita was 38,285 RMB (USD 5548 at the 2020 exchange rate) and the annual per capita disposable income of rural household was 13,143 RMB (USD 1905) in 2020 [38]. In 2013, the poverty incidence was 17.64% [39]. Jinggu is a typical poor Chinese county with a geographic disadvantage and a large percentage of ethnic minorities in the population. Its poverty alleviation strategy consists of major anti-poverty measures. Therefore, Jinggu County was chosen for a better understanding of China’s poverty alleviation implementation framework.

Figure 2.

Distribution of 832 impoverished counties (polygons in green color) in China and the case study county (Jinggu County, a polygon in red color).

Data on poor households and individuals used in this study were provided by Jinggu LGOP who was overseeing the poverty alleviation implementation (Table 1). This data on monitoring poor households and individuals covered the households that earned less than 1.5 times the monetary extreme poverty standard or had other difficulties, such as housing (whether they had safe houses) and health problems (whether any family member was seriously ill). In this case study, this paper first demonstrated the approaches towards poverty alleviation and their fundings under the implementation framework, and then analyzed the poor households’ income structure over time; all income data were converted to the constant price of 2020 to remove inflation influences. Finally, to attribute the increased income due to poverty alleviation interventions, this study compared the income of the poor group with the incomes of the whole Jinggu County and all rural China. The monitored poor household data was dynamic: new poor households and individuals were added, and non-poor households and individuals were removed from the dataset. However, the complete annual datasets reflecting the extreme poverty situation were comparable between years. For example, there was only a 3% difference between the average household income (48,302 RMB) containing all samples of 2020 and the average household income (49,835 RMB) that dropped the samples which did not appear in previous years. Thus, it was reasonable to keep the dataset with a larger sample size. The planned anti-poverty projects and their corresponding financial data were obtained from the Jinggu County Government official website [40], and the income of the Jinggu County and rural China were collected from statistic yearbooks [31,41].

Table 1.

Basic information of monitored poor households in Jinggu County.

2.3. Evaluations of Poverty Alleviation Effectiveness

This study compared the poor group in Jinggu County with the whole of rural China as a control group to investigate whether it was really the poverty alleviation campaign that caused the poor group’s income increase. Although the control group is not ideal as for example, as about 10% (56.3 million/590.2 million) of the population of the rural China group had also received poverty alleviation treatment, the comparisons could still provide an intuitive illustration of poverty alleviation results. A simple difference-in-difference analysis was conducted [42]. The difference-in-difference (D) was estimated by the equation:

where YT,2020 and YT,2015 are the incomes of treatment group in 2020 and 2015, respectively; likewise, YC,2020 and YC,2015 are the incomes of control group in 2020 and 2015, respectively.

An output to input ratio was also calculated to assess the effectiveness of poverty alleviation projects. The total annual income of the monitored poor households were set as output while the costs of poverty alleviation projects were treated as input. Since infrastructure, such as roads and bridges, can be used for decades, we depreciated those infrastructure projects by 15 years [43].

3. Results

3.1. Poverty Implementation Details in Rural China

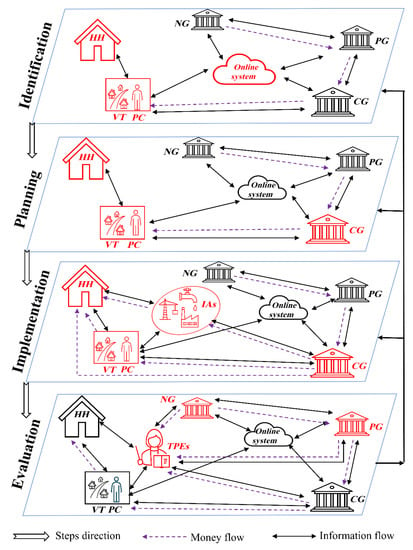

The implementation process consisted of four steps: identifying the poor, planning anti-poverty measures, implementing anti-poverty measures, and evaluating the results in terms of poverty alleviation (Figure 3). Many people and institutions were involved in the poverty alleviation campaign, including poor households and individuals, village resident working teams (experienced officials dispatched to villages to help the poor, members were called “poverty commissioners”), governments at different levels, companies, and educational and research institutions. Each institution or individual might play a different role at different steps, but they cooperated to achieve the common goal: poverty alleviation and rural development.

Figure 3.

Implementation process in China’s poverty alleviation. NG = national government, PG = provincial government, CG = county government, VT = village resident working team, PC = poverty commissioner, HH = household and individuals, IAs = implementation agents, TPEs = third party evaluators. The red color highlights the most important components in each step. Source: Authors’ deliberation.

The first step of poverty alleviation was to systemically identify the poor at the household level. At this step, two questions needed to be answered: who are the poor and why are they poor? A top-down preparation. which included setting principles and standards, publicizing information, and training staff, was held before carrying out poor household identification. In a bottom-up process, every villager could file an application. Village resident working teams and the representatives of villagers then discussed and verified the candidates and made the information public. Township government and county/prefecture LGOP further verified and finally confirmed who was qualified. The lists of poor households were reported to provincial and central governments. Simultaneously, the information of each household’s financial, educational, and health conditions were uploaded to an online system for further analysis. The identification was dynamic: each year the information was updated once to capture the newly identified poor households.

Once the identification step was finished, the next step was anti-poverty measure planning. The central and provincial LGOPs generated nine approaches and their corresponding supportive policies, as described in Section 2.1. Based on the conditions of each poor household and government policies, village resident working teams and the identified poor households worked together to develop poverty relief measures (e.g., farming, activity planning, and employment training) not only for the poor households but also for the whole village. The planned measures were then reported to higher government departments for approval. County/prefecture LGOPs developed poverty relief projects (e.g., infrastructure and industry projects) that covered several townships or even the whole county/prefecture, based on local conditions, together with the Development and Reform Commissions, which were responsible for developing the five-year plan.

In the implementation step, the fundamental task was to coordinate all stakeholders and manage budgets. Besides poor villagers being the main target participants, external implementation agents, such as construction companies, labor-intensive factories, training teachers, and agricultural technicians were also included. Therefore, poverty commissioners and county/prefecture LGOPs had to coordinate with all the participants to implement poverty alleviation projects smoothly. In regard to improving agricultural income, new crop varieties and sustainable farming practices were introduced or adopted, supported by professional technicians. In terms of creating new jobs, food processing factories and other labor-intensive companies were established, and jobs as forest rangers in ecological conservation areas were created for the poor. Infrastructure—such as paved roads and telecommunication—was built, connecting every village. Other poverty alleviation measures, such as free basic education, health insurance, government cash transfers, and relocation were also provided. Open tender was used to choose related contractors during project implementation. Another important issue was managing budgets. Several funding sources were used to finance poverty alleviation projects: government funds, industry funds, loans, and self-funds. Budgeted money was distributed along with projects and spent strictly on corresponding projects only. If money was left over after project completion, county/prefecture LGOPs merged the remaining money and allocated it to other projects. Details about this re-allocation were published.

Evaluation was the fourth step in the framework. Higher level government departments hired independent agencies (usually universities from other provinces) to evaluate the implementation process and results. Evaluation agencies designed a standard inspecting scheme, organized information collectors gathered required information from poor households and individuals, and analyzed the results. During the process, evaluation agencies also provided feedback to local stakeholders to improve the previous work (poor households and individual identification, anti-poverty measure planning, and project implementation). Alleged cases of corruption or misconduct were reported to the responsible prosecution office for further investigation. Moreover, the national audit office carried out annual special audits in 832 poor counties to correct any misuse of funds. Based on the poverty standards—adequate income, “two no-worries”, and “three guarantees”—evaluations provided judgment on who was out of poverty. Besides the evaluation of independent agencies, provincial governments also conducted cross investigations which meant provincial government A investigated counties in province B and provincial government B investigated counties in province C.

3.2. The Case Study of Jinggu County

To further demonstrate the framework and process of poverty alleviation implementation in China, this study chose one county—Jinggu County—to elaborate the details of the framework process and analyzed implementation results to show that the poverty alleviation in Jinggu County, guided by the framework and process, was effective and efficient. The reason this study chose one county was because county or prefecture governments were responsible for overseeing the implementation of poverty alleviation in China.

3.2.1. Jinggu’s Approach towards Poverty Alleviation

Since 2013, the Jinggu County Government held 46 meetings to emphasize the importance of poverty alleviation, mobilize staff dedicated to this campaign, and discuss the identification process. Precisely identifying real poor households was fundamental and quite a challenge as it was the basic approach leading to the question: who should be helped? As discussed in Section 3.1, the identification was a mixed top-down and bottom-up process. All of the rural population in Jinggu County were visited by village resident working teams who were assigned by county or higher government departments to collect poor households’ basic information, such as education, health, and assets. Based on the standards that included adequate income, “two no-worries”, and “three guarantees”, rural households were separated into poor and non-poor households. The participatory identification process was transparent to prevent any possible corruption, as it was not only supervised by higher government offices but also watched by all rural households. Additionally, village resident working teams visited poor households at least once a month to make sure all information was updated.

To solve the question of who would help the poor, 137 resident working teams consisting of 721 poverty commissioners were dispatched to different villages. They worked with local teams to identify poor households and help with the planning of anti-poverty measures, project implementation, and other related issues. Since 2015, the Huangpu District in Shanghai City, a wealthy eastern city, had assigned three officers and provided 124 million RMB (USD 18 million) of aid to help Jinggu County to eliminate extreme poverty.

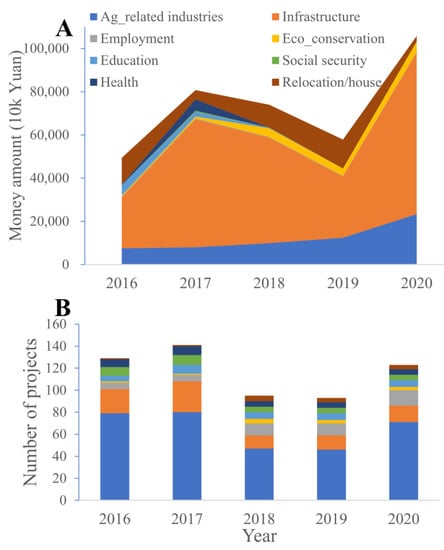

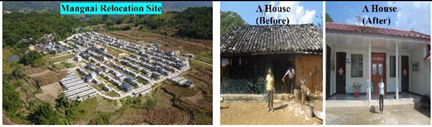

In terms of how to help the poor, Jinggu County developed many anti-poverty projects, which can be categorized into eight classes: (1) agricultural related industry development, (2) infrastructure development, (3) employment enhancement, (4) compensation of ecological conservation services, (5) education improvement, (6) social security or welfare programs, (7) health care improvement, and (8) relocation or house renovation (Figure 4, Appendix A Table A1). In the past five years of project implementation, infrastructure costed the most, at 2.4 billion RMB (USD 348 million), followed by agricultural industry development and relocation or house renovation which were 613 and 432 million RMB (USD 89 and 63 million), respectively (Figure 4A). Infrastructure development in rural villages focused on road paving, power grid upgrades, drinking water installation, telecommunication network installation, and living environment remediation (such as solid waste collection and waste water treatment). Over 300 agricultural industry development projects were implemented over the five years (Figure 4B). Projects included the introduction of cash crops, such as tea, sugarcane, fruit, and vegetables; setting up forest product companies, such as paper producing companies; introducing integrated crop and animal-keeping practices; setting up farmer cooperatives to help each other; and setting up food processing companies. A number of 3721 households (14,292 individuals) were relocated from their original vulnerable areas and 32,913 households’ homes were renovated (this data includes non-extreme poor households; if their houses were classified as unsafe, government subsidized the upgrade). More than 130,000 people received occupational training in order to find jobs locally or in other coastal provinces. Low-skilled positions (e.g., road cleaner and forest ranger) were created and provided for the poor. Free basic education was provided. Students from poor households received a monthly living allowance to avoid dropout during the compulsory education period. For poor university students, the central government provided tuition fee subsidies, living allowances, and low-interest loans. Other anti-poverty measures, like providing basic health care for all, micro-finance, subsistence allowance, and compensation for ecological conservation services, were also implemented during the five years of the program (Appendix A Table A1).

Figure 4.

Poverty alleviation projects and their financial support in Jinggu County. (A,B) share the same legend.

3.2.2. The Results of Jinggu’s Poverty Alleviation

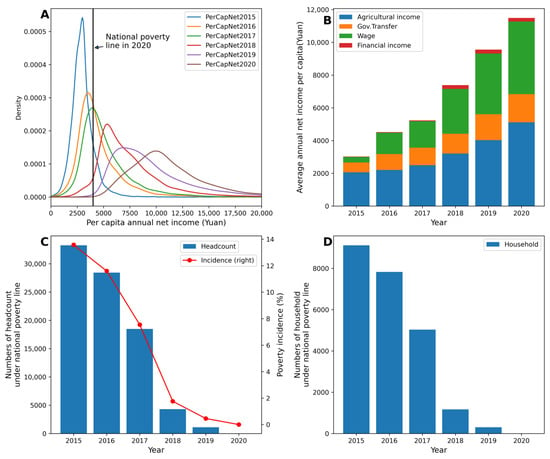

After more than five years of anti-poverty project implementation, the income of poor households had increased sharply (Figure 5). From 2015 to 2020, the income distribution shifted towards higher incomes, reaching a higher share of the population (Figure 5A). In 2015, many of the monitored households were under the national extreme poverty line (2300 RMB/year/capita in 2010 purchasing power parity which was similar to USD 1.9/day/capita in 2011 purchasing power parity) but none remained at that level in 2020. In terms of income structure, agricultural income still dominated the poor households with an average annual net income, followed by wages and government transfer payments (Figure 5B). The average annual agricultural income per capita increased from 2059 RMB (USD 298) in 2015 to 5114 RMB (USD 741) in 2020. However, wage income increased the fastest, from 338 RMB (USD 49) in 2015 to 4433 RMB (USD 642) in 2020. Financial income (e.g., dividends from collective owned companies) and government transfer payments were also increased steadily. As a result, the extreme poverty population decreased from over 30,000 individuals (incidence: 13.6%) in 2015 to 0 in 2020 (Figure 5C). Similarly, over 9000 extreme poverty households in 2015 were eliminated in 2020 (Figure 5D).

Figure 5.

The results of poverty alleviation in Jinggu County: (A) per capita net income distribution among the monitored poor population. (B) The structure of average per capita annual net income. (C) Individuals under the national poverty line (2300 RMB/year/capita, 2010 PPP). (D) Number of households under the national poverty line.

To fairly evaluate the poverty alleviation results, third parties from other provinces were invited to conduct on-site evaluations. At the household level, evaluation teams visited poor households to investigate whether they had: (1) adequate income to cover food, clothes, and safe housing, (2) clean drinking water, (3) health care and pension funds coverage, and (4) their children received at least basic education. At the village and county level, evaluation teams checked whether paved roads, electricity, broadcasting, and telecommunication had reached all villages. They also investigated whether the real poor were identified as the classified poor group and whether people positively appraised the poverty alleviation campaign. After the third party’s evaluation, Jinggu County was officially declared a non-poor county by the provincial government in 2019.

The poverty alleviation programs provided comprehensive changes for local population, based on a field visit in September 2021. Firstly, the living conditions had been improved: access to transport, electricity, communication, and drinking water were upgraded; public services, such as education, health, and social security, were guaranteed. Secondly, inequality within the local society had been reduced as income had increased through the poverty alleviation program. Thirdly, people’s mindset was enriched: the poor had more aspiration and confidence during the participation of poverty alleviation implementation. Fourthly, grass root governance was improved: better relationships between villagers and local officials, enhanced skills of officials, and a harmonized local social network provided solid governance ability. With the improved living conditions, the capacity of local people, and the social structure through the poverty alleviation campaign, Jinggu will be able to sustain the development in the future.

3.2.3. Evaluations of Poverty Alleviation Effectiveness

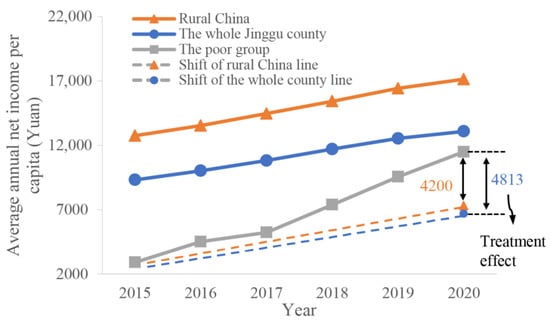

A different-in-different analysis was conducted to investigate whether poverty alleviation projects really contributed to income increases for poor households. As Figure 6 shows, from 2015 to 2020, the average annual income of the poor group in Jinggu County was growing faster than the control groups, and the difference-in-differences were 4813 and 4200 RMB (USD 698 and 609) when compared with the whole of Jinggu County and rural China, respectively. The results show that the poverty alleviation projects did favor the poor.

Figure 6.

The comparison of average annual net income of the poor group, the whole Jinggu County, and rural China. Rural China and the whole Jinggu County are set as control groups, and dash lines are their shifts.

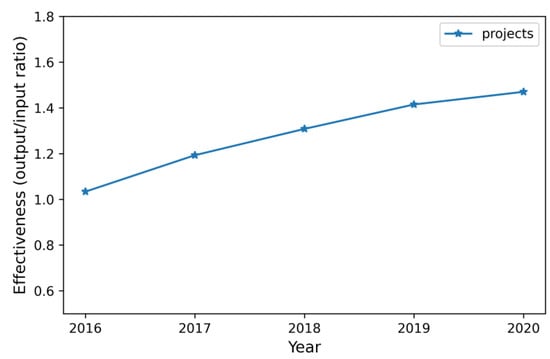

The overall effectiveness of poverty alleviation projects in Jinggu County was evaluated by calculating the output (the total annual income of poor households) to input (the cost of projects) ratio. The output to input ratios were from 1.03 To 1.47 in the past five year and the trend was increasing (Figure 7). The result revealed that the poverty alleviation projects were effective overall, as outputs were higher than inputs. The ratio was lower in short term but higher in long term, which was largely because much of the investment flew to infrastructure projects (Figure 4A) and it took a longer time to reap reward.

Figure 7.

The effectiveness of poverty alleviation projects in Jinggu County.

4. Discussion

Eliminating extreme poverty is a worldwide challenge, especially for low- and middle-income countries. Being able to live a better life is a fundamental human right and achieving this is a shared task of the world. This study presents China’s poverty alleviation campaign, conceptualization, and implementation framework and process and used one case to demonstrate the system in practice. China’s development-oriented poverty alleviation can provide experience and suggestions for other poverty alleviation programs and can contribute to the 2030 agenda of reaching the SDGs. The characteristics of China’s poverty alleviation program are further discussed and the limitations and suggestions are also given below.

4.1. The Characteristics of China’s Poverty Alleviation

The first characteristic is to set the national focus on the “normal people”. This people-centered philosophy makes the country willing to invest in economically inefficient programs that could improve the poor’s livelihood in remote areas and sometimes sacrifice economic growth [26]. Poverty alleviation has become a priority task of the Chinese government, especially since the year 2013. With this spirit in mind, three million poverty commissioners are willing to stay in villages to understand and to assist in the implementation of poverty alleviation programs. A people-centered philosophy also means that normal people play a dominating role in developing their lives. In China, poor people participate in the poverty alleviation program throughout the whole processes. Once the poor have external support and guidelines, they can overcome their difficulties and achieve endogenous development. This has also been reported in other developing countries’ poverty alleviation experiments [18]. To encourage poor people to participate in the poverty alleviation campaign, overcoming the negative stereotype of the poor and the stigma that is unfairly put onto the poor is necessary, as previous studies have highlighted [44,45]. Therefore, dignity and respect must be permeated throughout the poverty alleviation process.

Another clear characteristic is that a specialized institution—comparable to LGOP in China—is set up at different governmental levels to deal and coordinate poverty issues. This institution is not only responsible for making proper pro-poor policies but is also, more importantly, responsible for implementing these policies. Policies are ultimately transformed into different projects to reach poor households and individuals. The distinctive part of China’s poverty alleviation institution is the village resident working team. The grassroot team members contact the real poor and make sure that all policies are “down to earth”. Moreover, any corruption must be punished in the process of poverty alleviation through two supervision systems: the party discipline system and public prosecution systems.

The third characteristic is a development-oriented poverty alleviation strategy. Sustainable economic development is the critical driver in alleviating poverty [11]. Unlike developed countries whose poverty policies may focus on building a better welfare system to help the very poor, a developing country needs to “enlarge the cake” first and make a pro-poor distribution during the developing process as redistributing the “old cake” is much harder. Beyond normal public policies, such as providing free basic education and health care, China’s poverty alleviation program also implemented many economic development projects, such as improving agricultural productivity, introducing labor-friendly factories, and building infrastructure to every remote village. Usually, these pro-poor projects need government support as they are not profitable and the private sector is reluctant to step in.

In the development-oriented poverty alleviation strategy, agricultural development plays a major role in rural areas as agricultural income is still the main income resource for the poor. Many rural residents lack advanced skills and farming is their only economic activity. Thus, agricultural management is crucial for them. The best practices management, such as the prevention of soil erosion and water deprivation, pest and weed controls, nutrient management, the selection of suitable cultivar, the diversification of agricultural activities, and the adoption of new technologies, should be promoted continually [46,47,48]. Moreover, bringing external talents to rural areas and building a sustainable social–economic–ecological system is also important for rural development [49].

The fourth characteristic is that of anti-poverty measures are scientific and systemic and target the real poor. In the past, anti-poverty resources were allocated broadly to the impoverished regions in China. However, since 2013, the poor have been precisely targeted and the reasons why they are poor have been systemically identified and analyzed. Additionally, anti-poverty measures have been tailor-made case-by-case to make sure that they reflected reality and are implementable. Evaluations were conducted by academic researchers and all suggestions were used as feedback to improve the work of the local poverty alleviation teams.

The fifth characteristic is social mobilization. Since eliminating extreme poverty is a huge task, all social sectors must be mobilized to contribute to this campaign, such as government institutions, state-owned companies, private companies, local cooperatives, the poor, and non-government organizations. Coordinated by LGOP, different resources were pooled together to create synergies during the poverty alleviation period in China. Moreover, the eastern richer provinces sent staff and provided monetary aid to the western poorer provinces to help the fight against poverty. Encouraging the poor’s participation is also a key factor to successfully implementing poverty alleviation projects.

4.2. The Limitations and Suggestions

Due to the complexity of poverty, poverty alleviation programs are often linked with other social, economic, and ecological aspects, such as population changes, urbanization, economic structure changes, employment structure changes, agricultural land shrinking or abandonment, and environmental degradation [4,9,50,51]. Considering that these aspects are different from place to place, the framework presented in this study may not capture all aspects; therefore, policy makers may need to develop a place-based approach to capture local conditions [52,53]. However, China’s poverty alleviation implementation may provide some experience: each county or prefecture develops their specific implementation plan based on local conditions [25,54].

The occurrence of poverty may be of different reasons and features for different countries. Therefore, some of the poverty alleviation measures in this study may not suitable for other poverty alleviation programs. However, the framework presented in this study may help to answer whom to help, who will help, how to help, and when to help? The detailed implementation process described in this study can also provide an example for the developing world. Due to the heterogeneous of national priority, framework assumption, social and cultural legacy, institutional structure, and other local conditions, different countries may need to develop different approaches to eradicate extreme poverty.

The elimination of extreme poverty is not the end but the start of living a better life for the poor. Next, development policies and actions should tackle the relative poverty issues to pursue a common prosperity for society in the future. Subsequently, in 2020, China has launched the “rural revitalization” initiative to consolidate the achievements of extreme poverty alleviation. All existing policies and subsidies that fight against poverty will continue for at least five years; poor households and individuals are under monitoring and interventions are prepared in case they fall into extreme poverty again; sustainable expansions of local industries and investments in rural areas are encouraged [55]. Given the current achievements, such as improved living conditions and increased income, future development may need to focus on tackling social and spatial inequalities, increasing the resilience of livelihood from crises, and building a sustainable social-environmental system in the region [50,56,57].

Poverty interventions are reported in Indonesia, Ethiopia, Ghana, Honduras, India, Pakistan, Peru, and other places as well; the common interventions are cash or assets transfer [18,58], training and education system improvement [12,18,21], land system innovation [22], and ecological and agricultural support [19,23]. Comparing with previous experiences, this study combines many interventions together to address poverty issue. Poverty issue cannot be solved by cash or asset transfer alone [58], nor by the education system alone [21]. Therefore, it is advisable to develop a long-term strategy that integrates all interventions, such as agricultural development, employment expansion, social security net, and education and health guarantee. The criteria of poverty household identification in this study (income, “two no-worries”, and “three guarantees”) are different from other studies. While it adds costs and difficulties in practice, it can accurately identify the real poor and allow interventions to target them precisely.

5. Conclusions

Poverty alleviation is a worldwide challenge, particularly in terms of how to implement it successfully. This study describes an implementation framework which is based on a system approach, integrating a top-down preparation with a bottom-up implementation process, aiming to help establish poverty alleviation activities. The case study of Jinggu County reveals that the implementation of poverty alleviation action, guided by the framework and process, was effective and efficient. Employment expansion and agricultural development are effective ways to increase the poor’s income quickly. Investment in infrastructure is necessary to bring the poor out of poverty, although it may not be economically efficient in the short term. It is necessary to have functional and responsible institutions to implement anti-poverty policies. Other measures, such as providing basic education and health care, are also important to eliminate poverty in the long run. If possible, mobilizing the whole society to join the anti-poverty campaign can shorten the alleviation period. Moreover, poverty alleviation actions must be scientific and systematic, and put the common people, not the elites, first. The key characteristics of China’s poverty alleviation program, such as people-centered philosophy, pro-poor development, functional institution, systematic anti-poverty measures, and social mobilization, may be useful for other poverty alleviation implementation approaches. Due to the complexity of poverty, the framework in this study may not capture all aspects and the anti-poverty measures may also not suitable for other countries, but the novel implementation framework and process and pro-poor development strategy can provide valuable experience for other poverty alleviation programs. Future studies need to continue to track current projects to assess their long-term performance and make them sustainable and promote more similar poverty alleviation projects to eradicate extreme poverty and hunger worldwide.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.F., X.F. and A.J.; validation, J.F.; resources, J.F. and S.L.; data curation, S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.F.; writing—review and editing, J.F., A.J., S.L., X.F. and R.G.; visualization, J.F.; supervision, X.F.; project administration, R.G.; funding acquisition, X.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Yunnan Provincial Science and Technology Department under the program “High-end Foreign Experts” and the Provincial Academician (Expert) Workstation Project of Yunnan (grant number: 202205AF150028).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author or the first author.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate Jinggu LGOP for providing poor household data. We would also thank the editors and anonymous reviewers for their insightful suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

The details of anti-poverty measures in Jinggu County in the past five years.

Table A1.

The details of anti-poverty measures in Jinggu County in the past five years.

| Measures | Details | Examples (Photos) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture-related industry |

|  | |

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| Infrastructure |

|  | |

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| Employment |

|  | |

| |||

| |||

| |||

| Ecological compensation |

|  | |

| |||

| Education |

|  | |

| |||

| |||

| Health |

|  | |

| |||

| |||

| |||

| Social security |

| ||

| |||

| Relocation or house renovation |

|  | |

| |||

References

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf (accessed on 13 July 2021).

- Hickel, J. The True Extent of Global Poverty and Hunger: Questioning the Good News Narrative of the Millennium Development Goals. Third World Q. 2016, 37, 749–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2020. 2021. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/poverty-and-shared-prosperity (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Sachs, J. The End of Poverty: Economic Possibilities for Our Time; Penguin Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-1-59420-045-9. [Google Scholar]

- Stiglitz, J.E. The Great Divide: Unequal Societies and What We Can Do about Them; W.W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rank, M.R.; Yoon, H.-S.; Hirschl, T.A. American Poverty as a Structural Failing: Evidence and Arguments. J. Sociol. Soc. Welf. 2003, 30, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Mansi, E.; Hysa, E.; Panait, M.; Voica, M.C. Poverty—A Challenge for Economic Development? Evidences from Western Balkan Countries and the European Union. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J.F. The Paradox of Progressing Sideways: Food Poverty and Livelihood Change in the Rice Lands of Outer Island Indonesia. J. Peasant. Stud. 2020, 47, 1077–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, R. Rural Poverty and Impoverished Theory: Cultural Populism, Ecofeminism, and Global Justice. J. Peasant. Stud. 2007, 34, 167–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, C. Development Strategies and Rural Development: Exploring Synergies, Eradicating Poverty. J. Peasant. Stud. 2009, 36, 103–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nallari, R.; Griffith, B. Understanding Growth and Poverty: Theory, Policy, and Empirics; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0-8213-6953-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.P. Knowledge Transfer Models and Poverty Alleviation in Developing Countries: Critical Approaches and Foresight. Third World Q. 2019, 40, 1209–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lade, S.J.; Haider, L.J.; Engström, G.; Schlüter, M. Resilience Offers Escape from Trapped Thinking on Poverty Alleviation. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1603043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, C.; Carter, M. The Economics of Poverty Traps and Persistent Poverty: Empirical and Policy Implications. J. Dev. Stud. 2013, 49, 976–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, L.J.; Boonstra, W.J.; Peterson, G.D.; Schlüter, M. Traps and Sustainable Development in Rural Areas: A Review. World Dev. 2018, 101, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Banerjee, A.V.; Duflo, E. Poor Economics: A Radical Rethinking of the Way to Fight Global Poverty, 1st ed.; PublicAffairs: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1-58648-798-0. [Google Scholar]

- Alkire, S.; Santos, M.E. Measuring Acute Poverty in the Developing World: Robustness and Scope of the Multidimensional Poverty Index. World Dev. 2014, 59, 251–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Duflo, E.; Goldberg, N.; Karlan, D.; Osei, R.; Pariente, W.; Shapiro, J.; Thuysbaert, B.; Udry, C. A Multifaceted Program Causes Lasting Progress for the Very Poor: Evidence from Six Countries. Science 2015, 348, 1260799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraro, P.J.; Simorangkir, R. Conditional Cash Transfers to Alleviate Poverty Also Reduced Deforestation in Indonesia. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaaz1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumarto, S.; Suryahadi, A.; Widyanti, W. Designs and Implementation of Indonesian Social Safety Net Programs. Dev. Econ. 2002, 40, 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.; James, D. Educational Expansion, Poverty Reduction and Social Mobility: Reframing the Debate. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 100, 101537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Guo, L.; Liu, Y. Land Consolidation Boosting Poverty Alleviation in China: Theory and Practice. Land Use Policy 2019, 82, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Fan, X.; Jintrawet, A.; Weyerhaeuser, H. Sustainability intervention on Agro-Ecosystems: An Experience from Yunnan Province, China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Fei, D.; Huang, Q.; Jiang, L.; Shi, P. Targeted Poverty Alleviation through Photovoltaic-Based Intervention: Rhetoric and Reality in Qinghai, China. World Dev. 2021, 137, 105117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y. Targeted Poverty Alleviation and Its Practices in Rural China: A Case Study of Fuping County, Hebei Province. J. Rural. Stud. 2022, 93, 430–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Poverty Alleviation: China’s Experience and Contribution; Foreign Languages Press: Beijing, China, 2021.

- United Nations Development Program China. Report on Sustainable Financing for Poverty Alleviation in China. 2016. Available online: https://www.cn.undp.org/content/china/en/home/library/poverty/sustainable-financing-for-poverty-alleviation-in-china.html (accessed on 13 July 2021).

- Rogers, S.; Li, J.; Lo, K.; Guo, H.; Li, C. China’s Rapidly Evolving Practice of Poverty Resettlement: Moving Millions to Eliminate Poverty. Dev. Policy Rev. 2020, 38, 541–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, C.; Pan, J. The Effect of the Health Poverty Alleviation Project on Financial Risk Protection for Rural Residents: Evidence from Chishui City, China. Int. J. Equity Health 2019, 18, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Bank Open Data. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/topic/poverty (accessed on 25 August 2021).

- National Bureau of Statistic of China. China Statistic Yearbook 2020; China Statistic Press: Beijing, China, 2020.

- Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Y. Spatio-Temporal Patterns of Rural Poverty in China and Targeted Poverty Alleviation Strategies. J. Rural. Stud. 2017, 52, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.; Hitchins, D.; Eisner, H. What Is the Systems Approach? Insight 2010, 13, 41–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Kustiwan, I. Understanding Poverty in the Development Context and Poverty Reduction Policy Using System Dynamics Approach. In Proceedings of the Achieving and Sustaining SDGs 2018 Conference: Harnessing the Power of Frontier Technology to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (ASSDG 2018), Bandung, Indonesia, 18 October 2018; Atlantis Press: Bandung, Indonesia, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, T.; Jiang, Z.; Zhao, W.; Guo, Z.; Liu, B.; Mu, L.; Lv, J.; Xiao, L.; Wang, C.; et al. Precision Poverty-Alleviation Big Data Platform. 2016. Patent No. CN105260978A, 2016. filed 26 October 2015, and issued 20 January 2016. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/CN105260978A/en (accessed on 3 June 2021).

- The State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Outline of Development-Driven Poverty Alleviation in Rural Areas (2011–2020). 2011. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2011/content_2020905.htm (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- The State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Notice of the State Council on the 13th Five-Year Plan for Poverty Alleviation. 2016. Available online: http://www.cpad.gov.cn/art/2016/12/3/art_46_56101.html (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Jinggu County Government. Introduction of Jinggu County. 2020. Available online: http://jinggu.gov.cn/jggk/jgjj.htm (accessed on 3 June 2021).

- Yunnan Net. Jinggu County Will Not Stop Fighting Until Winning the Poverty Alleviation Battle. 2020. Available online: https://puer.yunnan.cn/system/2020/08/21/030904071.shtml (accessed on 3 June 2021).

- Jinggu County Government. Government Information for Public. 2020. Available online: http://jinggu.gov.cn/xxgk/list.jsp?urltype=tree.TreeTempUrl&wbtreeid=1800 (accessed on 3 June 2021).

- Yunnan Statistic Bureau. Yunnan Statistic Yearbook 2015–2020; China Statistic Press: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bharadwaj, P. Quasi Experimental Methods: Difference in Differences. 2010. Available online: http://cega.berkeley.edu/assets/cega_learning_materials/78/DnD_Quasi_Experimental_Methods_PBharadwaj_100324.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2021).

- Internal Revenue Service. How to Depreciate Property. 2021. Available online: https://www.irs.gov/publications/p946 (accessed on 26 August 2022).

- Meij, E.; Haartsen, T.; Meijering, L. Enduring Rural Poverty: Stigma, Class Practices and Social Networks in a Town in the Groninger Veenkoloniën. J. Rural. Stud. 2020, 79, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, C.M. Understanding Persistent Poverty: Social Class Context in Rural Communities1. Rural. Sociol. 1996, 61, 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkari, C.; Robin Bryant, C. Toward Improved Adoption of Best Management Practices (BMPs) in the Lake Erie Basin: Perspectives from Resilience and Agricultural Innovation Literature. Agriculture 2017, 7, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huttunen, S. Revisiting Agricultural Modernisation: Interconnected Farming Practices Driving Rural Development at the Farm Level. J. Rural. Stud. 2019, 71, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, B.; Corsi, S.; Gbehounou, G.; Kienzle, J.; Taguchi, M.; Friedrich, T. Sustainable Weed Management for Conservation Agriculture: Options for Smallholder Farmers. Agriculture 2018, 8, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Ma, L.; Zhang, Y.; Qu, L. Multifunctional Rural Development in China: Pattern, Process and Mechanism. Habitat Int. 2022, 121, 102530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsoulakos, N.M.; Misthos, L.-M.N.; Doulos, I.G.; Kotsios, V.S. Chapter 8—Environment and Development. In Environment and Development; Poulopoulos, S.G., Inglezakis, V.J., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; ISBN 978-0-444-62733-9. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, X.; Fu, Z.; Deng, X.; Xu, D. The Impact of Livelihood Risk on Farmers of Different Poverty Types: Based on the Study of Typical Areas in Sichuan Province. Agriculture 2021, 11, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchens, C.; Wallace, C.T. The Impact of Place-Based Poverty Relief: Evidence from the Federal Promise Zone Program. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2021, 95, 103735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zheng, J.; Hite, D. The Neighborhood Effects of a Place-Based Policy—Causal Evidence from Atlanta’s Economic Development Priority Areas. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Su, B.; Liu, Y. Realizing Targeted Poverty Alleviation in China: People’s Voices, Implementation Challenges and Policy Implications. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2016, 8, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Opinions on the Smooth Transition from Consolidation of Poverty Alleviation Achievement to Rural Revitalization. 2020. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2021/content_5598113.htm (accessed on 4 August 2021).

- Su, F.; Song, N.; Ma, N.; Sultanaliev, A.; Ma, J.; Xue, B.; Fahad, S. An Assessment of Poverty Alleviation Measures and Sustainable Livelihood Capability of Farm Households in Rural China: A Sustainable Livelihood Approach. Agriculture 2021, 11, 1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glazebrook, T.; Noll, S.; Opoku, E. Gender Matters: Climate Change, Gender Bias, and Women’s Farming in the Global South and North. Agriculture 2020, 10, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arham, M.A.; Hatu, R. Does Village Fund Transfer Address the Issue of Inequality and Poverty? A Lesson from Indonesia. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).