Grape Quality Zoning and Selective Harvesting in Small Vineyards—To Adopt or Not to Adopt

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Information costs, related to the necessary investments in the technology, including rental fees for specific hardware or machinery;

- Costs involving data processing, specific licence fees, software and hardware products for data analysis;

- Learning costs, mainly due to the additional time required for the farmer to develop management schemes, calibration of the machinery, as well as “lost” opportunity costs due to inefficient use of the precision agriculture technology.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Characterisation of the Study Area

2.2. Sampling and Measurement of Vegetative, Yield, and Grape Components

2.3. UAV-Based Image Acquisition and Vegetation Index Analyses

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Data Collection and Analysis on the Economic Efficiency of Grape Quality Zoning and Selective Harvesting

3. Results

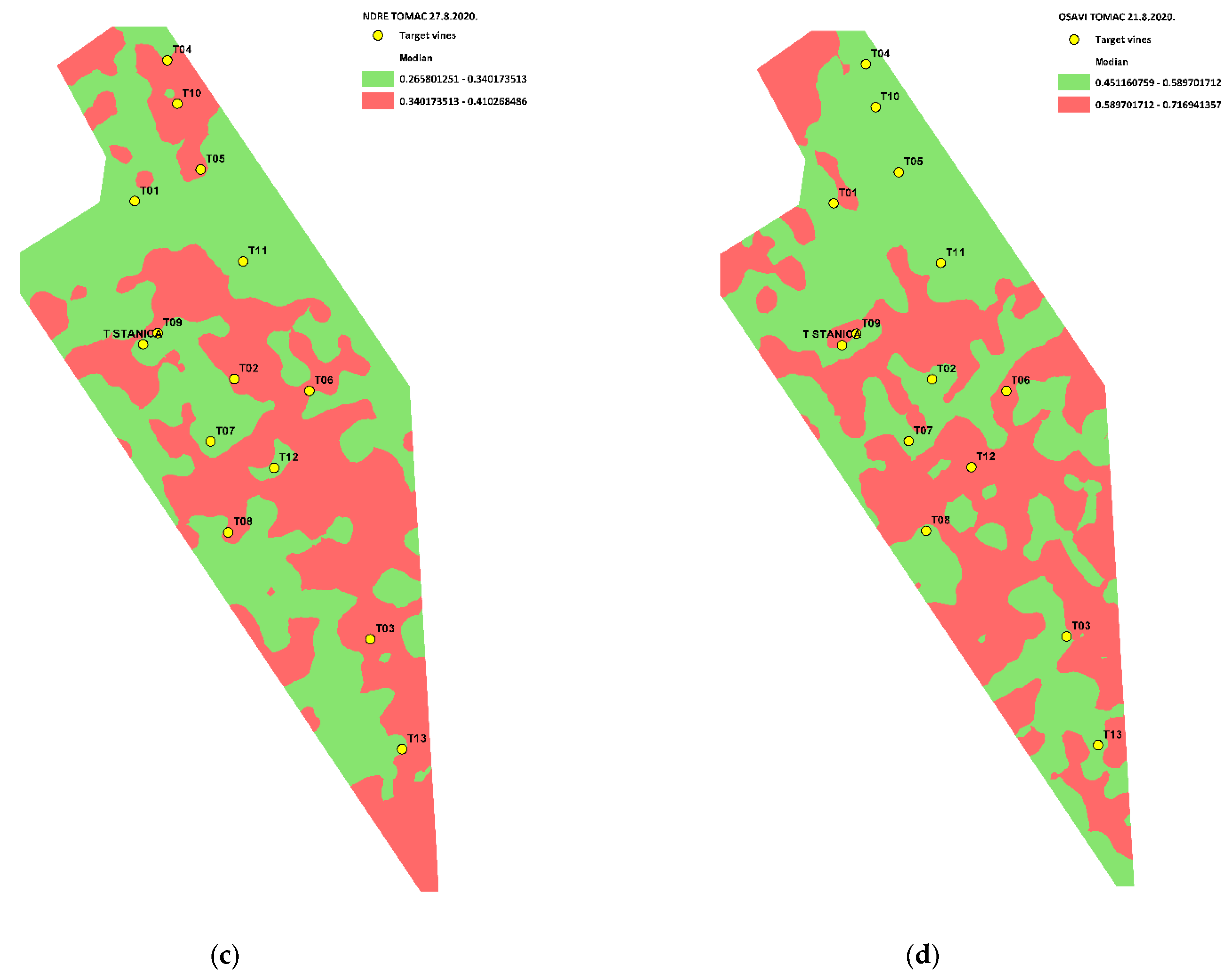

3.1. The Most Predictive Vegetation Index in 2019 and 2020–TOMAC Site

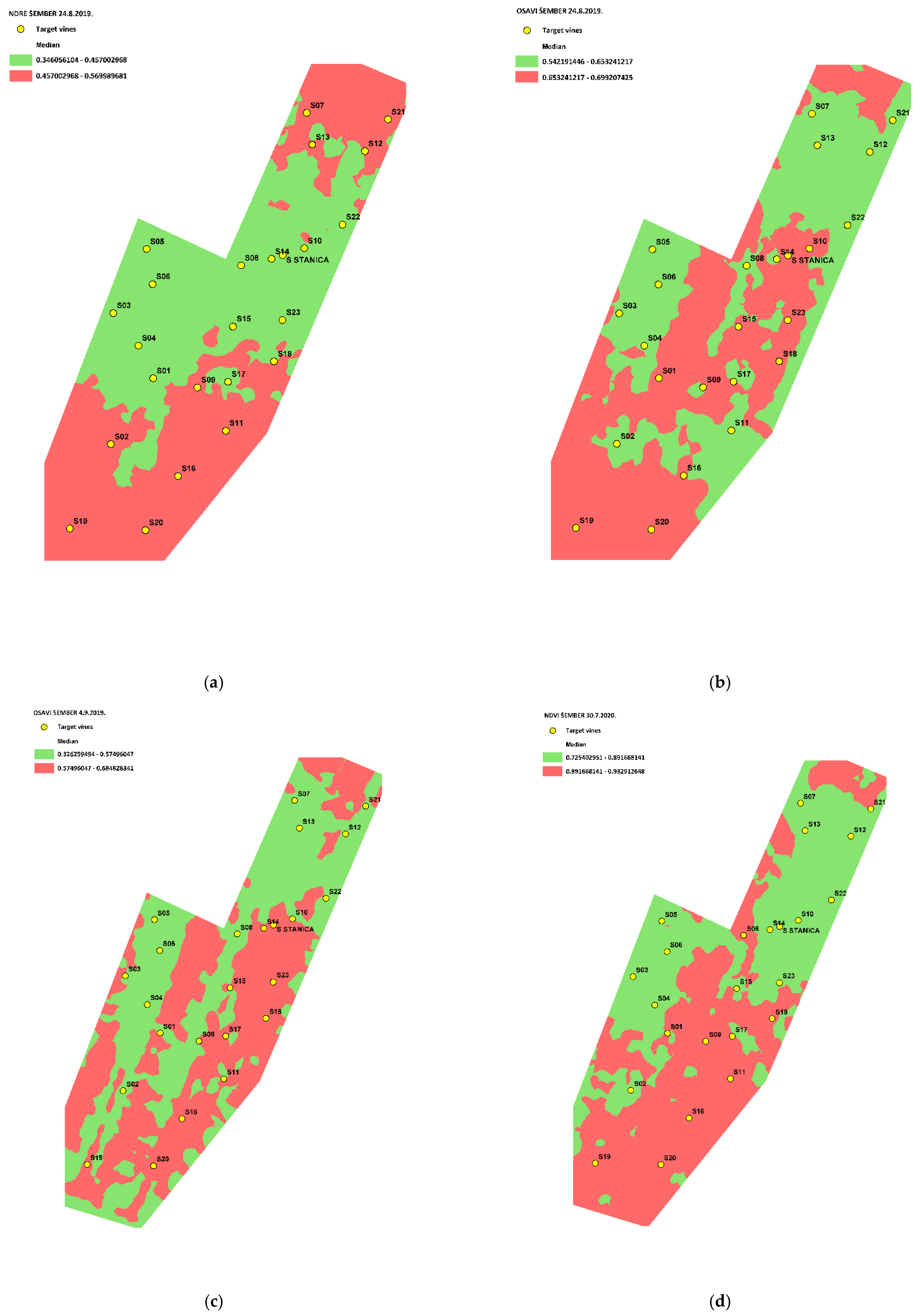

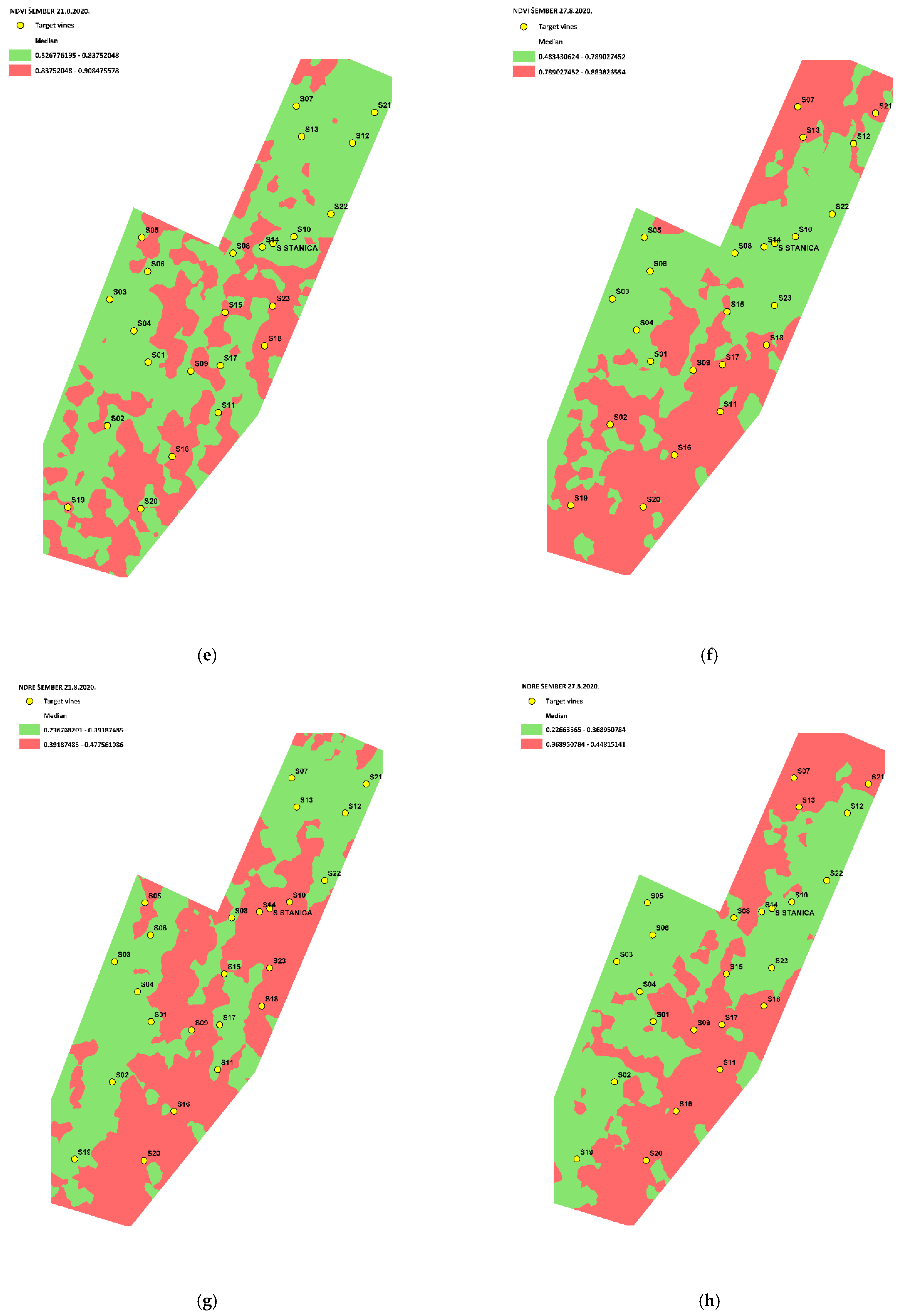

3.2. The Most Predictive Vegetation Index in 2019 and 2020–ŠEMBER Site

3.3. Economic Efficiency of Grape Quality Zoning and Selective Harvesting

3.3.1. Fixed and Variable Costs of Grape Quality Zoning and Selective Harvesting

3.3.2. Pinot Noir Wine Prices in the Plešivica Subregion

3.3.3. Potential Revenues after Grape Quality Zoning and Selective Harvesting

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bramley, R.G.V. 12—Precision Viticulture: Managing vineyard variability for improved quality outcomes. In Managing Wine Quality; Reynolds, A.G., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2010; pp. 445–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, H.D. An Economic Analysis of Precision Viticulture, Fruit, and Pre Release Wine Pricing across Three Western Australian Cabernet Sauvignon Vineyards. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Environment and Agriculture, Curtin University, Perth, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Steyn, J.; Aleixandre-Tudo, J.L.; Aleixandre, J.L. Grapevine Vigour and Within-Vineyard Variability: A Review. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 2016, 7, 1056–1065. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, L.F.; Bosch, D.F.; Williams, D.C.; Lobitz, B.M. Remote sensing of vineyard management zones: Implications for wine quality. Appl. Eng. Agric. 2001, 17, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Casasnovas, J.A.; Agelet-Fernandez, J.; Arnó, J.; Ramos, C. Analysis of vineyard differential management zones and relation to vine development, grape maturity and quality. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2012, 10, 326–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fiorillo, E.; Crisci, A.; De Filippis, T.; Di Gennaro, S.F.; Di Blasi, S.; Matese, A.; Primicerio, J.; Vaccari, F.P.; Genesio, L. Airborne high-resolution images for grape classification: Changes in correlation between technological and late maturity in Sangiovece vineyard in Central Italy. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2012, 18, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippetti, I.; Allegro, G.; Valentini, G.; Pastore, C.; Colucci, E.; Intrieri, C. Influence of vigour on vine performance and berry composition of cv. Sangiovese (Vitis vinifera L.). J. Int. Des Sci. De La Vigne Et Du Vin 2013, 47, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Santesteban, L.G.; Guillaume, S.; Royo, J.B.; Tisseyre, B. Are precision agriculture tools and methods relevant at the whole-vineyard scale? Precis. Agric. 2013, 14, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Urretavizcaya, I.; Santesteban, L.G.; Tisseyre, B.; Guillaume, S. Oenological significance of vineyard management zones delineated using early grape sampling. Precis. Agric. 2014, 15, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bonilla, I.; Martinez de Toda, F.; Martinez-Casanovas, J.A. Vine vigour, yield and grape quality assessment by airborne remote sensing over three years: Analysis of unexpected relationships in cv. Tempranillo. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2015, 13, e0903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Blu, R.; Molina, M. Evaluation of vegetation indices and apparent soil electrical conductivity for site-specific vineyard management in Chile. Precis. Agric. 2016, 17, 434–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledderhof, D.; Brown, R.; Reynolds, A.; Jollineau, M. Using remote sensing to understand Pinot noir vineyard variability in Ontario. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2016, 96, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, M.; Garavani, A.; Vercesi, A.; Poni, S. Ground-truthing of remotely sensed within-field variability in a cv. Barbera plot for improving vineyard management. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2017, 23, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matese, A.; Di Gennaro, S.; Miranda, C.; Berton, A.; Santesteban, L. Evaluation of spectral-based and canopy-based vegetation indices from UAV and Sentinel 2 images to assess spatial variability and ground vine parameters. Adv. Anim. Biosci. 2017, 8, 817–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastonchi, L.; Di Gennaro, S.F.; Toscano, P.; Matese, A. Comparison between satellite and ground data with UAV-based information to analyse vineyard spatio-temporal variability. OENO One 2020, 54, 919–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, M.; Echeverria, G.; Pereyra, G.; Gonzales-Neves, G.; Pan, D.; Miras-Avalos, J.M. Mapping vineyard vigour using airborne remote sensing: Relations with yield, berry composition and sanitary status under humid conditions. Precis. Agric. 2020, 21, 178–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldoni, H.; Costa, B.R.S.; Bognola, I.A.; de Souza, C.R.; Bassoi, L.H. Homogeneous zones of vegetation index for characterizing variability and site-specific management in vineyards. Sci. Agric. 2021, 78, e20190243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, A.G.; Brown, R.; Jollineau, M.; Shemrock, A.; Lee, H.; Dorin, B.; Shabanian, M.; Meng, B. Viticultural Mapping by UAVs, Part 2 Applying Unmanned Aerial Vehicles in Viticulture. The Free Library. Wines Vines. 2018. Available online: https://www.thefreelibrary.com/Viticultural+Mapping+by+UAVs%2c+Part+2%3a+Applying+unmanned+aerial…-a0546959785 (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Poni, S.; Gatti, M.; Palliotti, A.; Dai, Z.; Duchêne, E.; Truong, T.T.; Ferrara, G.; Matarrese, A.; Gallotta, A.; Bellincontro, A.; et al. Grapevine quality: A multiple choice issue. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 234, 445–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lambert, D.M.; Lowenberg-DeBoer, J.; Griffin, T.W.; Peone, J.; Payne, T.; Daberkow, S.G. Adoption, Profitability, and Making Better Use of Precision Farming Data; Staff Papers 28615; Purdue University, Department of Agricultural Economics: West Lafayette, Indiana, 2004; Available online: https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/28615 (accessed on 13 February 2021).

- Tisseyre, B.; Taylor, J.A. An overview of methodologies and technologies for implementing precision agriculture in viticulture. In Proceedings of the XII Congresso Brasileiro de Vitivinicultura e Enologia, Bento Goncavles, RS, Brasil, 22–24 September 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Matese, A.; Di Gennaro, S.F. Practical Applications of a Multisensor UAV Platform Based on Multispectral, Thermal and RGB High Resolution Images in Precision Viticulture. Agriculture 2018, 8, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andújar, D.; Moreno, H.; Bengochea-Guevara, J.; De Castro, A.; Ribeiro, A. Aerial imagery or on-ground detection? An economic analysis for vineyard crops. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 157, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramley, R.G.V.; Pearse, B.; Chamberlain, P. Being profitable precisely—A case study of precision viticulture from Margaret River. Aust. New Zealand Grapegrow. Winemak. 2003, 84–87. [Google Scholar]

- Proffit, T.; Malcom, A. Zonal vineyard management through airborne remote sensing. Aust. New Zealand Grapegrow. Winemak. 2005, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Joint Research Centre (JRC) of the European Commission; Monitoring Agriculture ResourceS (MARS) Unit H04; Pablo, J.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J.; Hubbard, N.; Loudjani, P. Precision Agriculture: An Opportunity for EU Farmers—Potential Support with the CAP 2014-2020. European Parliamnet, Directorate-General for Internal Policies, 2014. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/note/join/2014/529049/IPOL-AGRI_NT%282014%29529049_EN.pdf (accessed on 13 February 2021).

- Grgić, Z.; Očić, V.; Šakić Bobić, B. Troškovi i Kalkulacije u Agrobiznisu; Internal Students Book; Faculty of Agriculture: Zagreb, Croatia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bramley, R.G.V.; Proffitt, A.P.B.; Hinze, C.J.; Pearse, B.; Hamilton, R.P. Generating benefits from precision viticulture through selective harvesting. In Proceedings of the 5th European Conference on Precision Agriculture-Precision agriculture ’05, Uppsala, Sweden, 9–12 June 2005; pp. 891–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramley, R.G.V.; Ouzman, J.; Thornton, C. Selective harvesting is a feasible and profitabile strategy even when grape and wine production is geared towards large fermentation volumes. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2011, 17, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, J.; Lefevre, V.; Douche, H.; Poilve, H.; Habimana, T. Oenoview®: Remote Sensing in Support of Vineyard Profitability and Wine Quality. Acta Hortic. 2013, 978, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maletić, E.; Karoglan Kontić, J.; Pejić, I. Vinova Loza Ampelografija, Ekologija, Oplemenjivanje; Školska Knjiga: Zagreb, Croatia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mirošević, N.; Alpeza, I.; Bolić, J.; Brkan, B.; Hruškar, M.; Husnjak, S.; Jelaska, V.; Karoglan Kontić, J.; Maletić, E.; Mihaljević, B.; et al. Atlas Hrvatskog Vinogradarstva i Vinarstva; Golden Marketing—Tehnička Knjiga: Zagreb, Croatia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Coombe, B.G. Adoption of a system for identifying grapevine growth stages. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 1995, 1, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delenne, C.; Durrieu, S.; Rabatel, G.; Deshayes, M. From pixel to vine parcel: A complete methodology for vineyard delineation and characterization using remote-sensing data. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2010, 70, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Comba, L.; Gay, P.; Primicerio, J.; Ricauda Aimonino, D. Vineyard detection from unmanned aerial systems images. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2015, 114, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, A.P.; Park, S.; O’Connell, M.; Fuentes, S.; Ryu, D.; Chung, H. Automated detection and segmentation of vine rows using high resolution UAS imagery in a commercial vineyard. In Proceedings of the 21st International Congress on Modelling and Simulation, MODSIM 2015, Broadbeach, Queensland, Australia, 29 November–4 December 2015; pp. 1406–1412. [Google Scholar]

- Primicerio, J.; Gay, P.; Ricauda Aimonino, D.; Comba, L.; Matese, A.; Di Gennaro, S. NDVI-based vigour maps production using automatic detection of vine rows in ultra-high resolution aerial images. In Precision Agriculture ’15, Proceedings of 10th European Conference on Precision Agriculture, Israel, 12–16 July 2015; Stafford, J.V., Ed.; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 465–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Castro, A.I.; Jiménez-Brenes, F.M.; Torres-Sánchez, J.; Peña, J.M.; Borra-Serrano, I.; López-Granados, F. 3-D Characterization of Vineyards Using a Novel UAV Imagery-Based OBIA Procedure for Precision Viticulture Applications. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pádua, L.; Marques, P.; Adão, T.; Guimarães, N.; Sousa, A.; Peres, E.; Sousa, J. Vineyard Variability Analysis through UAV-Based Vigour Maps to Assess Climate Change Impacts. Agronomy 2019, 9, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Campos, J.; García-Ruíz, F.; Gil, E. Assessment of Vineyard Canopy Characteristics from Vigour Maps Obtained Using UAV and Satellite Imagery. Sensors 2021, 21, 2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouse, J.W.; Haas, R.H.; Schell, J.A.; Deering, D.W. Monitoring vegetation systems in the Great Plains with ERTS. In Proceedings of the 3rd ERTS Symposium, Washington, DC, USA, 10–14 December 1973; NASA: Washington, DC, USA NASA SP-351. ; pp. 309–317. [Google Scholar]

- Buschmann, C.; Nagel, E. In Vivo Spectroscopy and Internal Optics of Leaves as Basis for Remote Sensing of Vegetation. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1993, 14, 711–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondeaux, G.; Steven, M.; Baret, F. Optimization of Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Indices. Remote Sens. Environ. 1996, 55, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinton, S.M.; Ahmad, M. Returns to Farmer Investments in Precision Agriculture Equipment and Services. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Precision Agriculture, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 23–26 June 1996; American Society of Agronomy, Crop Science Society of America, Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1996; pp. 1009–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidman, C.; Pagay, V.; Jenkins, A. Optimizing Water Use Efficiency for Improved Wine Quality in Coonawarra Vineyards Using Remote Sensing Technologies—Season 2. Final Report. 2017. Available online: https://coonawarra.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/CWGI-Final-report-310517.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2021).

- Xue, J.; Su, B. Significant Remote Sensing Vegetation Indices: A Review of Developments and Application. J. Sens. 2017, 2017, 1353691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fern, R.; Foxley, E.; Bruno, A.; Morrison, M. Suitability of NDVI and OSAVI as estimators of green biomass and coverage in a semi-arid rangeland. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 94, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soubry, I.; Patias, P.; Tsioukas, V. Monitoring vineyards with UAV and multi-sensors for the assessment of water stress and grape maturity. J. Unmanned Veh. Syst. 2016, 5, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Candiago, S.; Remondino, F.; De Giglio, M.; Dubbini, M.; Gattelli, M. Evaluating Multispectral Images and Vegetation Indices for Precision Farming Applications from UAV Images. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 4026–4047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lamb, D.W.; Weedon, M.M.; Bramley, R.G.V. Using remote sensing to map grape phenolics and colour in a cabernet sauvignon vineyard—The impact of image resolution and vine phenology. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2004, 10, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bonilla, I.; Martínez de Toda, F.; Martínez-Casasnovas, J.A. Vineyard zonal management for grape quality assessment by combining airborne remote sensed imagery and soil sensors. In Remote Sensing for Agriculture, Ecosystems, and Hydrology XVI, Proceedings of SPIE Remote Sensing, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 11 November 2014; SPIE Digital Library: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kazmierski, M.; Glémas, P.; Rousseau, J.; Tisseyre, B. Temporal stability of within-field patterns of NDVI in non irrigated Mediterranean vineyards. OENO One 2011, 45, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D‘Urso, M.G.; Rotondi, A.; Gagliardini, M. UAV low-cost system for evaluating and monitoring the growth parameters of crops. In ISPRS Annals of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences 2018, IV-5, Proceedings of ISPRS TC V Mid-term Symposium “Geospatial Technology—Pixel to People”, Dehradun, India, 20–23 November 2018; Kumar, A.S., Saran, S., Padalia, H., Eds.; ISPRS: Hannover, Germany, 2018; pp. 405–413. [Google Scholar]

- Sozzi, M.; Cantalamessa, S.; Cogato, A.; Kayad, A.; Marinello, F. Grape yield spatial variability assessment using YOLOv4 object detection algorithm. In Proceedings of the 13th European Conference on Precision Agriculture, Budapest, Hungary, 19–22 July 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sozzi, M.; Cogato, A.; Boscaro, D.; Kayad, A.; Tomasi, D.; Marinello, F. Validation of a commercial optoelectronics device for grape quality analysis. In Proceedings of the 13th European Conference on Precision Agriculture, Budapest, Hungary, 19–22 July 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shockley, J.; Mark, T.; Dillon, C. Educating producers on the profitability of precision agriculture technologies. Adv. Anim. Biosci. 2017, 8, 724–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Grape Quality Components | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 (n = 9) | F (1,7) | Sig. | First Cluster (n = 2) | Second Cluster (n = 7) |

| M ± SD | M ± SD | |||

| Sugar concentration (°Oe) | 8.365 | 0.023 | 91.00 ± 4.24 | 84.71 ± 2.36 |

| Total titratable acidity (g/L) | 10.647 | 0.014 | 5.56 ± 0.55 | 6.83 ± 0.47 |

| pH | 7.402 | 0.030 | 3.15 ± 0.02 | 3.09 ± 0.03 |

| 2020 (n = 13) | F (1,11) | Sig. | First cluster (n = 5) | Second cluster (n = 8) |

| M ± SD | M ± SD | |||

| Sugar concentration (°Oe) | 13.162 | 0.004 | 88.00 ± 3.39 | 81.00 ± 3.38 |

| Total titratable acidity (g/L) | 3.703 | 0.081 | 6.86 ± 0.85 | 7.66 ± 0.65 |

| pH | 1.776 | 0.210 | 3.09 ± 0.08 | 3.01 ± 0.11 |

| Vegetation Index | NDRE | NDVI | OSAVI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UAV image acquisition | GS 34 | GS 36 | GS 38 | GS 34 | GS 36 | GS 38 | GS 34 | GS 36 | GS 38 |

| 2019 (n = 9) | |||||||||

| Number of equally classified vines | 4 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Percentage of equally classified vines | 44% | 78% | 78% | 78% | 67% | 89% | 67% | 67% | 67% |

| 2020 (n = 13) | |||||||||

| Number of equally classified vines | 8 | 7 | 11 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 8 |

| Percentage of equally classified vines | 62% | 54% | 85% | 62% | 62% | 54% | 62% | 46% | 62% |

| Analysed Variables | High-Vigour Target Vines (n = 6) | Low-Vigour Target Vines (n = 3) | SS of Differences (Average) Results/Ranks | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M ± SD (CV) | Shapiro–Wilk | M ± SD (CV) | Shapiro–Wilk | F | t (7) | Mann–Whitney U | |

| Sugar concentration (°Oe) | 84.33 ± 2.34 (2.77) | 0.836 | 89.67 ± 3.79 (4.22) | 0.855 | 1.514 | −2.667 * | |

| Total titratable acidity (g/L) | 6.90 ± 0.49 (7.04) | 0.898 | 5.86 ± 0.65 (11.01) | 0.984 | 0.146 | 2.739 * | |

| Yield (kg) | 2.71 ± 0.61 (22.56) | 0.860 | 1.56 ± 0.77 (49.32) | 0.896 | 0.184 | 2.448 * | |

| Analysed Variables | High-Vigour Target Vines (n = 8) | Low-Vigour Target Vines (n = 5) | SS of Differences (Average) Results/Ranks | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M ± SD (CV) | Shapiro–Wilk | M ± SD (CV) | Shapiro–Wilk | F | t (11) | Mann–Whitney U | |

| Sugar concentration (°Oe) | 81.13 ± 3.52 (4.34) | 0.901 | 87.80 ± 3.63 (4.14) | 0.914 | 0.015 | −3.286 ** | |

| Total titratable acidity (g/L) | 7.75 ± 0.62 (8.01) | 0.924 | 6.73 ± 0.70 (10.40) | 0.973 | 0.063 | 2.749 * | |

| Grape Quality Components | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 (n = 12) | F (1,10) | Sig. | First Cluster (n = 4) | Second Cluster (n = 8) |

| M ± SD | M ± SD | |||

| Sugar concentration (°Oe) | 32.502 | 0.000 | 75.75 ± 2.22 | 84.63 ± 2.67 |

| Total titratable acidity (g/L) | 10.146 | 0.010 | 9.84 ± 1.08 | 8.02 ± 0.86 |

| pH | 26.378 | 0.000 | 2.93 ± 0.02 | 3.07 ± 0.05 |

| 2020 (n = 22) | F (1,20) | Sig. | First cluster (n = 13) | Second cluster (n = 9) |

| M ± SD | M ± SD | |||

| Sugar concentration (°Oe) | 40.046 | 0.000 | 84.15 ± 3.02 | 94.22 ± 4.47 |

| Total titratable acidity (g/L) | 4.063 | 0.057 | 7.69 ± 1.84 | 6.27 ± 1.23 |

| pH | 8.492 | 0.009 | 3.07 ± 0.11 | 3.21 ± 0.11 |

| Vegetation Index | NDRE | NDVI | OSAVI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UAV image acquisition | GS 34 | GS 36 | GS 38 | GS 34 | GS 36 | GS 38 | GS 34 | GS 36 | GS 38 |

| 2019 (n = 12) | |||||||||

| Number of equally classified vines | 7 | 9 | 6 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 8 | 5 | 5 |

| Percentage of equally classified vines | 58% | 75% | 50% | 67% | 58% | 50% | 67% | 42% | 42% |

| 2020 (n = 22) | |||||||||

| Number of equally classified vines | 16 | 15 | 15 | 19 | 15 | 15 | 17 | 16 | 16 |

| Percentage of equally classified vines | 73% | 68% | 68% | 86% | 68% | 68% | 77% | 73% | 73% |

| Analysed Variables | High-Vigour Target Vines (n = 7) | Low-Vigour Target Vines (n = 5) | SS of Differences (Average) Results/Ranks | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M ± SD (CV) | Shapiro–Wilk | M ± SD (CV) | Shapiro–Wilk | F | t (10) | Mann–Whitney U | |

| Sugar concentration (°Oe) | 78.29 ± 3.55 (4.53) | 0.729 ** | 86.40 ± 1.34 (1.55) | 0.552 *** | 0.000 ** | ||

| Total titratable acidity (g/L) | 9.32 ± 1.07 (11.49) | 0.934 | 7.66 ± 0.83 (10.89) | 0.914 | 0.115 | 2.872 * | |

| pH | 2.98 ± 0.07 (2.20) | 0.805 * | 3.08 ± 0.06 (2.07) | 0.818 | 3.000 * | ||

| Leaf N content (% on a dry matter basis) | 2.21 ± 0.12 (5.28) | 0.926 | 2.01 ± 0.10 (4.94) | 0.843 | 0.278 | 3.009 * | |

| Analysed Variables | High-Vigour Target Vines (n = 10) | Low-Vigour Target Vines (n = 12) | SS of Differences (Average) Results/Ranks | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M ± SD (CV) | Shapiro–Wilk | M ± SD (CV) | Shapiro–Wilk | F | t (20) | Mann–Whitney U | |

| Sugar concentration (°Oe) | 83.40 ± 3.06 (3.67) | 0.974 | 92.33 ± 5.12 (5.55) | 0.925 | 2.532 | −4.831 *** | |

| Total titratable acidity (g/L) | 8.05 ± 1.93 (23.93) | 0.768 ** | 6.33 ± 1.12 (17.78) | 0.840 * | 19.000 ** | ||

| pH | 3.05 ± 0.11 (3.54) | 0.921 | 3.19 ± 0.11 (3.31) | 0.957 | 0.034 | −3.136 ** | |

| Leaf N content (% on a dry matter basis) | 1.98 ± 0.10 (4.99) | 0.978 | 1.86 ± 0.10 (5.14) | 0.903 | 0.053 | 2.914 ** | |

| Fixed Costs–Equipment Purchase Costs | PRICE (EUR) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DJI Phantom 4 Multispectral UAV | 5600.00 | |||

| Additional battery | 160.00 | |||

| Computer for data processing | 1300.00 | |||

| Software Pix4D | 2600.00 | |||

| DPO crew mandatory training for drone pilot | 530.00 | |||

| Training for the UAV image analysis and data processing (Pix4D fields) | 1000.00 | |||

| Insurance and registration of UAV | 1000.00 | |||

| TOTAL | 12,190.00 | |||

| Variable Human Labour Costs (1 ha) | Time required | EUR/h | Quantity | PRICE (EUR) |

| Manual sampling on target vines | 4 | 6.70 | 3 | 80.40 |

| Education on the use of UAV | 30 | 6.70 | 1 | 201.00 |

| Education on the data processing | 40 | 6.70 | 1 | 268.00 |

| UAV data acquisition | 3 | 6.70 | 3 | 60.30 |

| Data processing and creation of quality zones | 3 | 6.70 | 3 | 60.30 |

| Selective harvesting | 220 | 3.30 | 1 | 726.00 |

| Extra costs of selective harvesting | 50 | 3.30 | 1 | 165.00 |

| TOTAL | 1561.00 | |||

| Variable Service Costs | Area (ha) | EUR/ha | PRICE (EUR) | |

| COMMERCIAL SERVICE–UAV image acquisition | 1 | 400.00 | 3 | 1200.00 |

| COMMERCIAL SERVICE–data processing | 1 | 400.00 | 3 | 1200.00 |

| TOTAL | 2400.00 |

| Wine | Market (Retail) Price (EUR/Bottle 0.75 l) |

|---|---|

| Pinot noir Šember Vučjak * | 20.00 |

| Sparkling wine Šember Rose * | 16.00 |

| Pinot noir Tomac * | 19.33 |

| Sparkling wine Tomac Rose * | 16.67 |

| Pinot Noir Wine From the Plešivica Subregion | |

| Pinot noir Ledić * | 4.66 |

| Pinot noir Filipec * | 10.66 |

| Pinot noir Braje * | 11.33 |

| Pinot noir Šoškić * | 13.60 |

| Average Market Price | 10.07 |

| TOMAC Site | ŠEMBER Site | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 2019 | 2020 | 2019 | 2020 |

| Vineyard area (ha) | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.65 | 0.65 |

| Quantity of grapes harvested (kg) | 1800 | 0.900 | 6570 | 4815 |

| Amount of produced wine (l) | 1260 | 1330 | 599 | 3371 |

| Number of produced bottles (0.75 l) (pcs) | 1680 | 1773 | 6132 | 4494 |

| Average bottle price (EUR/bottle 0.75 l) | 10.07 | 10.07 | 10.07 | 10.07 |

| Sales revenue without selective harvesting (EUR) | 16,917.60 | 17,854.11 | 61,749.24 | 45,254.58 |

| Percentage of low-vigour zone (%) | 61.97 | 54.33 | 49.47 | 47 |

| Percentage of high-vigour zone (%) | 38.03 | 45.67 | 50.53 | 53 |

| Number of produced bottles from low-vigour zone (pcs) | 1041 | 963 | 3034 | 2112 |

| Number of produced bottles from high-vigour zone (pcs) | 639 | 810 | 3098 | 2382 |

| Wine price from low-vigour zone (EUR/bottle 0.75 l) | 19.33 | 19.33 | 20 | 20 |

| Wine price from high-vigour zone (EUR/bottle 0.75 l) | 16.67 | 16.67 | 16 | 16 |

| Total revenue from low-vigour zone (EUR) | 20,122.53 | 18,614.79 | 60,680.00 | 42,240.00 |

| Total revenue from high-vigour zone (EUR) | 10,652.13 | 13,502.70 | 49,568.00 | 38,112.00 |

| Potential sales revenue after selective harvesting (EUR) | 30,774.66 | 32,117.49 | 110,248.00 | 80,352.00 |

| Potential revenue increase after selective harvesting (EUR) | 13,857.06 | 14,263.38 | 48,498.76 | 35,097.42 |

| Potential revenue increase after selective harvesting (%) | 45.03 | 44.41 | 43.99 | 43.68 |

| TOMAC Site | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | S2 | |||||||

| A1 | A2 | Differential Amount | A2 Is: | A1 | A2 | Differential Amount | A2 Is: | |

| Sales revenue (EUR) | 16,917.60 | 30,774.66 | 13,857.06 | higher | 16,917.60 | 30,774.66 | 13,857.06 | higher |

| Variable costs (EUR) | 0.00 | 829.36 | 829.36 | higher | 0.00 | 2694.03 | 2694.03 | higher |

| Fixed costs (EUR) | 0.00 | 12,190.00 | 12,190.00 | higher | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | equal |

| Profit (EUR) | 16,917.60 | 17,755.30 | 837.70 | higher | 16,917.60 | 28,080.63 | 11,163.03 | higher |

| ŠEMBER Site | ||||||||

| S1 | S2 | |||||||

| A1 | A2 | Differential Amount | A2 Is: | A1 | A2 | Differential Amount | A2 Is: | |

| Sales revenue (EUR) | 61,749.24 | 110,248.00 | 48,498.76 | higher | 61,749.24 | 110,248.00 | 48,498.76 | higher |

| Variable costs (EUR) | 0.00 | 1178.80 | 1178.80 | higher | 0.00 | 2979.15 | 2979.15 | higher |

| Fixed costs (EUR) | 0.00 | 12,190.00 | 12,190.00 | higher | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | equal |

| Profit (EUR) | 61,749.24 | 96,879.20 | 35,129.96 | higher | 61,749.24 | 107,268.85 | 45,519.61 | higher |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rendulić Jelušić, I.; Šakić Bobić, B.; Grgić, Z.; Žiković, S.; Osrečak, M.; Puhelek, I.; Anić, M.; Karoglan, M. Grape Quality Zoning and Selective Harvesting in Small Vineyards—To Adopt or Not to Adopt. Agriculture 2022, 12, 852. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12060852

Rendulić Jelušić I, Šakić Bobić B, Grgić Z, Žiković S, Osrečak M, Puhelek I, Anić M, Karoglan M. Grape Quality Zoning and Selective Harvesting in Small Vineyards—To Adopt or Not to Adopt. Agriculture. 2022; 12(6):852. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12060852

Chicago/Turabian StyleRendulić Jelušić, Ivana, Branka Šakić Bobić, Zoran Grgić, Saša Žiković, Mirela Osrečak, Ivana Puhelek, Marina Anić, and Marko Karoglan. 2022. "Grape Quality Zoning and Selective Harvesting in Small Vineyards—To Adopt or Not to Adopt" Agriculture 12, no. 6: 852. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12060852

APA StyleRendulić Jelušić, I., Šakić Bobić, B., Grgić, Z., Žiković, S., Osrečak, M., Puhelek, I., Anić, M., & Karoglan, M. (2022). Grape Quality Zoning and Selective Harvesting in Small Vineyards—To Adopt or Not to Adopt. Agriculture, 12(6), 852. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12060852