1. Introduction

Wine tourism, development, and the marketing of wine tourism represent a relatively recent phenomenon [

1], even in those countries not traditionally considered wine countries [

2,

3]. Additionally, well known as enotourism, oenotourism, or vinitourism [

4], wine tourism has many definitions, dimensions, and significances and it is a relatively new form of tourism that has developed in wine-producing countries and/or regions and found under the shape of the “wine road” for the first time [

5]. The definition of wine tourism is not uniform because it can be analyzed from different perspectives, such as marketing or the motivation of travelers [

6].

The European Charter on Oenotourism [

7] defines enotourism as “the development of all tourists and “spare time” activities, dedicated to the discovery and to the cultural and wine knowledge pleasure of the vine, the wine and its soil” [

7]. Getz [

8] defined wine tourism as travel related to the appeal of wineries and wine country [

8], and Hall and Sharples [

9,

10] and Hall and Macionis [

11] defined it as “visitation to vineyards, wineries, wine festivals and wine shows for which grape wine tasting and/or experiencing the attributes of a grape wine region are the prime motivating factors for visitors” [

11]. Charters and Ali-Knight [

12] mentioned that the main aim of wine tourism is “to offer the opportunity of experiences wineries and wine regions, including the lifestyles of its people” [

12]. Anastasiadis & Alebaki [

13] defined wine tourism as an emerging form of tourism that incorporates a wide set of activities and infrastructure.

In Europe, wine tourism was often associated with official wine routes and wine roads [

9]. Olaru [

1] mentioned three main components for wine tourism: (1) visit of wine connoisseurs and buyers, (2) visit to vineyards, and (3) wine routes. However, most importantly, the research on wine tourism suggests and promotes the idea that food and wine can be, and often are, the primary reason to travel to a certain region and not necessarily a secondary activity of the trip [

6].

Wine tourism is a rapidly growing field of industry [

14,

15,

16] worldwide [

15], with more than 40 million tourists visiting wineries each year [

17]. A growing area of special interest tourism is in “New World” wine countries [

18]. Academic interest has focused on the changes in the consumer markets in recent years, showing an enormous interest in

experiential travel [

10] but also recognizing niche tourism [

14,

19]. Wine is often associated with relaxation, communication with friends, and hospitality [

1,

20]. Visiting wineries and attending a wine route is a product of wine tourism [

21]. Nowadays, tourists wish to enjoy diverse rather than mono-cultural environments [

22], and good gastronomy has turned into a need for modern society [

22] together with wine tasting to improve visitors’ experience [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27].

Regarding the producers of wine, there are two important types [

28,

29]: (1) Old World producers, including the majority of European countries, such as France, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Romania, and Hungary; (2) New World wine regions such as Australia, Argentina, Chile, United States, the Czech Republic, or South Africa [

30,

31]. At the international level, there are internet pages dedicated to promoting wine regions recognized as wine capitals [

32] as follows: Bilbao, Bordeaux, Cape Town, Firenze, Porto, San Francisco, etc.

Wine tourism is a complex activity and an important way to learn about people, culture, and heritage [

22], as it is deeply integrated into the local culture [

33] at different levels, including luxury private wine tours [

34,

35], such as in Spain, for example, which ranks second in the world for UNESCO heritage sites, between Italy (rank 1) and France (rank 3), all of these countries are the top wine producers [

36] and attract the most wine tourism. More, France, for example, created a national label to promote wine tourism, “Vignobles & Découvertes” [

37], to find all the wine tourism activities offered along the wine routes easily. Australia recommends luxury culinary tourism opportunities as tourism experiences, [

6,

27,

35] mentioned the 4E strategies, including education [

12], wine tasting and seminars, home wine-making seminars, or even wine-making tourism, such as in Poland’s rural areas [

2]. Due to the activities linked to wine tourism, the motivation for travel are diverse due to several different factors, and some of these vary by country [

12,

14,

38]:

For health benefits of wine consumption in moderation for tourists who visit parts of Europe and Asia [

15];

For social, fun activities with friends for tourists in the US and Australia [

25,

39];

Festivals [

22] and food and drink events [

26,

38];

For the architecture or art in the wineries [

38];

To see nature and participate in ecotourism [

39];

For food and wine matching [

38];

For cultural or romantic reasons [

39].

For all of these activities related to wine tourism, there are examples in the international literature of the best practices used worldwide for good wine tourism, both for locals and tourists [

38]: wine roads, wine community/unique partnerships, special food and wine events and festivals, experiential wine programs, wine and regional tourism/ecotourism/green tourism, wine villages, wine, and art and architecture.

In line with all these particularities and many connections of wine tourism with other leisure activities, it is important to mention the six pillars of European Enotourism [

5,

14,

40]: (1) wine culture, (2) tourism, (3) territory, (4) sustainability, (5) authenticity, and (6) competitiveness. More, the importance of wine tourism was marked by the UNWTO Global Conference on Wine Tourism [

41], which declared it a crucial component of gastronomic tourism [

41]. In 2018 at the 3rd UNWTO Global Conference on Wine Tourism in Moldova, [

42] the stakeholders focused on wine tourism as a tool for rural development [

42].

At the same time, there are smaller segments of wine consumers who are motivated to visit wine regions because of the architecture or art in the wineries, to see nature and participate in ecotourism, for food and wine matching, or for cultural or romantic reasons [

39]. Motivations that research shows are common to most wine tourists, however, are the desire to taste new wines, learn about them, and see how the wine is made.

In the international scientific literature, there are two attempts to frame wine tourism [

8,

43]: macroeconomics and microeconomics. Poitras & Getz [

44] mentioned the strategic problems of wine tourism research: (1) at the national level when we speak about marketing and branding and (2) at the regional level when we speak about regional identity, image, and branding [

23].

As a product, wine tourism implies two dimensions: the wineries and the regions where the wineries are located. Basically, the tourism and wine industries are based on the branding of the area [

1]. To resume the infrastructure of Romania and the Republic of Moldova for wine tourism, we take two important references into consideration that describe the development process of wine tourism: (i) the marketing and branding of the wine industry and (ii) the infrastructure and activities to attract the potential tourists for wine tourism (wine roots, food and/or wine festivals, visiting of the winery and/or wine cellars, participating at wine production, etc.).

In Romania and Moldova, there are wines with Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) and wines with Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) [

1,

6], which are presented in the next section. Each wine route tries to highlight a set of regional features, which provide brand identity and a distinctive note [

1].

The base for the development of wine tourism is cultural and historic heritage [

39]. A wine destination’s potential is expressed by [

45]: the country’s and/or region’s history, folklore, the national drink, and folk crafts. Wine tourism can be developed through [

46]: expanding content by including intangible goods and expanding the territorial domain (cities, vineyard landscapes, cultural roots).

There are many international studies regarding wine tourism [

4] for countries such as [

6] the United States, France, New Zealand, Australia, South Africa, Spain, Chile, Canada, and Italy, but we identified in the literature that there are no comparative studies between two countries (from Old World or New World), especially between countries from top 20 worldwide wine producers and/or exporters.

Therefore, our research fills a gap in the international literature through a cross-cultural comparison [

47] between two important countries from the Old World of wine producers. The aim of this paper is to analyze—qualitatively and quantitatively [

48]—if there are statistically significant differences between Romanian and Moldavian tourists in regards to wine tourism, to discover their motivations, and to model their motivations by using, as independent variables, the socio-demographic characteristic [

22] and specific variables for travel and tourism activities. We want to find out how much wine tourism is considered by the Romanian and Moldavian tourists as a leisure activity or an experiential one. The main motivation to choose these countries for comparison is based on the common cultural elements of these countries, the common history, and the spiritual strengths of the countries, including the gastronomic and wine culture. Additionally, we take into consideration the cultural—touristic route “Voievod Ștefan cel Mare și Sfânt” (Voivode Stephen the Great and Saint) as a common effort to promote common historical elements of these countries with a number of 24 touristic objectives from Romania and 30 from the Republic of Moldova. This paper offers the first comparative profile of wine tourists from Romania and Moldova in the international literature being a small number of papers dedicated to Moldova [

49,

50,

51] and Romania [

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58].

Brief Description of Romania and Republic of Moldova in Wine Tourism Context

The comparative statistical data for wine and tourism industries from Romania and the Republic of Moldova are presented in

Table 1. The evolution of wine indicators during the period 1995–2019, according to OIV—the International Organization of Vine and Wine— is presented in

Figure 1 [

36]. Additionally, the period 2020–2022 is an atypical one for tourism; we will retain only the statistical data for tourism for 2019.

According to the OIV Report [

36], Moldova has continued its downward trend that started in 2018, reaching a vineyard surface area of 140 kha, explained by the ongoing process of the restructuring and transformation of its vineyards [

36]. Romania has also decreased by 190 kha, which is a decrease of 0.4% compared with 2019 [

36]. Romania has 2.6% of the total world vineyard surface area, and the Republic of Moldova has 1.9% [

36]. In 2018, Romania occupied 10th place at the world level for main vineyards and Moldova placed 13th worldwide for major wine producers, Moldova placed 20th. Romania was in 13th place for major wine consumption in 2018, but Moldova placed 12th worldwide among main wine exporters in 2018 as quantitative but not in billion euros [

61].

Figure 1.

The premium wine, PGI and PDO vineyards map for Romania. Source: [

36,

62]. (Legend: grey color is for PGI and PDO areas; green color is for DOC APVR—Association for Promoting the Romanian Wine; red color is for wine region; icon symbol for wine press indicates the Romanian premium wine).

Figure 1.

The premium wine, PGI and PDO vineyards map for Romania. Source: [

36,

62]. (Legend: grey color is for PGI and PDO areas; green color is for DOC APVR—Association for Promoting the Romanian Wine; red color is for wine region; icon symbol for wine press indicates the Romanian premium wine).

To create a quality product related to wine, it is necessary to have not only Protected designation of origin (PDOs) and Protected designation of origin (PGIs) but also routes associated with those products [

6]. The wine regions for Romania are presented in

Figure 1 with the Protected geographical indication (PGI) and Protected designation of origin (PDO) marked on the map. Romania has [

1]:

Seven wine regions are as follows: Podisul Transilvaniei, Dealurile Moldovei, Dealurile Munteniei and Olteniei, Dealurile Banatului, Dealurile Crisanei and Maramuresului, Dealurile Dobrogei, Terasele Dunării

Nine famous vineyards offering wine tasting itineraries: Murfatlar, Urlățeanu Cellar, Seciu, Ștefănești, Minis, Jidvei, Panciu, Bucium, Recaș.

There are also museums of wine: Murfatlar, Drăgășani, Ștefănești (Golești Argeș), Huși, Odobești, Minis, Hârlău.

Romania [

36], as of 2019, produces 3808 thousand hectoliters, exports 236 thousand hectoliters, has 230 varieties, 45 geographical indication (IG)/appellation of origin (AO), and provides 17 training courses with 191,181 ha of vineyard (

Figure 2).

For the Republic of Moldova, a country with a long-standing tradition of wine production [

51], the PGI map is presented in

Figure 3. Additionally, Moldova has 18 wine roots with dedicated internet pages in English, Romanian and Russian [

63]:

https://wineofmoldova.com/en (accesed on 11 July 2022)/. According to this site, the Republic of Moldova has four wine regions PGI-Codru wine region, Ștefan Vodă wine region, Valul lui Traian wine region, and the Divine wine region—and two PDO regions—Ciumai and Românești.

As of 2019 [

36], the Republic of Moldova produced 1460 thousand hectoliters, exported 1509 thousand hectoliters, had 105 varieties, and six IG/AO with 142,800 ha of vineyard (

Figure 4).

To promote Romanian wine, there are some dedicated internet pages (in Romanian and English languages) that are as follows:

www.crameromania.ro [

64] and

www.crameromania.ro/en/regions (for wineries) [

65],

www.revino.ro (including all the wineries and wine stores, restaurants, and cellars), Revino Salon [

66]. All of these activities are completed by numerous gastronomic and wine festivals such as Revino Bucharest, RO–Wine Bucharest, WineUp Fair–Cluj Napoca, and Vinvest–Timișoara. Additionally, by using the mobile application Winebook Romania [

67] (

https://play.google.com), consumers can score wine products based on the ROVINTIS Research Project [

53].

For the Republic of Moldova, tourism agencies present yearly wine routes and tourist guides due to the positive evolution of this type of tourism activity in recent years. The most visited wine cellars and wineries in the Republic of Moldova are The Mileștii Mici, Purcari, and Cricova.

In Romania, the most visited wine cellars and wineries are Vila Vinea, Rotemberg, and Rasova; Romania is an important European wine producer country [

1] from the “Old World”.

2. Materials and Methods

According to the aim and the objectives of the research, we applied an online self-administrated questionnaire [

22,

52,

55,

57,

68,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73,

74]. The data were collected from 5 March to 1 June 2021. The questionnaires were distributed in Romania and the Republic of Moldova in the native language of the respondents through convenience sampling [

13,

22,

43,

47,

75], with a filter question regarding the practicing or not of wine tourism and the possibility to continue only for positive answers. The questionnaire has 14 questions structured in two sections according to the research objectives: section A with 8 questions regarding wine tourism and section B with 8 questions referring to the socio-demographic data describing the wine tourists’ profile.

The research sample had 359 respondents—171 from Romania and 188 from the Republic of Moldova. The comparative structure of the samples’ socio-demographic characteristics is presented in

Table 2. The average age of the Romanian and Moldavian respondents was the same, 31 years old. The average income per person for Romanian tourists was 1700 lei, and for Moldavian tourists, it was 1425 lei. Moreover, the distribution of the samples according to age was approximately the same for the Romanian and Moldavian participants, age being one of the determinant variables of the wine tourists’ profiles.

For the horizontal analysis, absolute and relative frequencies were used. A Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient [

22] was applied to test the internal consistency of the items. The results highlighted an acceptable index to reinforce the validity of the research work conducted, with an acceptance value close to 0.700.

The normal distribution was assessed for the socio-demographic characteristics of the samples, and one sample of the Lilliefors-corrected Kolmogorov–Smirnov test indicated non-normal distributions (p = 0.000). Therefore, non-parametric statistical tests were used.

To analyze if there were statistically significant differences between the Moldavian and Romanian tourists, we applied non-parametrical statistical methods due to the categorical data of the research, respectively, the chi-square bivariate test, Mann–Whitney U test, and Kruskal–Wallis, with p < 0.05.

To model the wine tourists’ profiles for Moldova and Romania, we applied linear regression analysis in two situations: (1) with motivation as a dependent variable (effect) and the socio-demographic characteristics as independent variables, and (2) with motivation as a dependent variable (effect) and the specific variables for travel (accommodation, frequencies of visits, average stay) as independent variables, inside of each group, respectively, for Romania and the Republic of Moldova.

For the qualitative analysis [

15,

24,

76,

77] of the co-occurrence link between terms from Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus scientific articles, the VOSviewer software version 1.6.18 (retrieved from

https://www.vosviewer.com/) [

78] was used to create the map of the keywords from title and abstracts of the scientific indexed articles [

79,

80,

81] selected base on “wine tourism” search. Several (880) articles from WoS and 698 articles from Scopus were found. For Romania, 25 articles from WoS and 26 articles from Scopus were found, and for Moldova, only 3 articles from Wos and 8 were found from the Scopus database. The results of the analysis are presented in the next section of the paper. The motivation for this analysis is to demonstrate the lack of scientific research for Romania and the Republic of Moldova for wine tourism and to justify the necessity of our study.

For the quantitative analysis based on statistical methods of the collected data through questionnaire, the SPSS 23.0 (licensed) software was used, and Microsoft Excel for graphical representations. In the Results section of the article, all the research results are presented comparatively, not separately, for Romania and the Republic of Moldova.

3. Results

3.1. Results for Qualitative Analysis (Co-Occurrence Link between Terms with VOSviewer)

For the analysis based on the co-occurrence link between the terms linked to “wine tourism”, we decided only to use the Web of Science (Clarivate Analytics) and Scopus database. For this analysis, the VOSviewer software was used to create a map for each scientific database based on network data. As inputs, the bibliographic database files from WoS and Scopus were used as inputs to VOSviewer. The items were created starting with the keywords/term “wine tourism” in the topic field of the publication from these databases. We opted to retain the main fields of the results, that is, the title and the abstracts, respectively, due to the full text of the articles not being freely available. We followed all recommendations of the VOSviewer software’s authors [

79,

80,

81], which are described in the software manual.

Figure 5 shows the results for the WoS articles. Several (880) articles were identified. The terms were grouped into three clusters as follows:

Cluster 1 (red color) that includes terms such as vineyard, resources, tourism development, culinary tourism, rural area, rural tourism, hotel identity, history, and long tradition; these terms define, in fact, all of the complementary activities and specific products and services related to wine tourism;

Cluster 2 (green color), including terms such as visitors, wine tourist, satisfaction, motivation, behavior, intention, wine tasting, wine festivals, and authenticity. These terms practically define the wine tourists;

Cluster 3 (blue color) includes terms that refer to the methodology used for this research, most of them by using the interview with representative firms/companies.

Figure 6 shows the results for the Scopus abstracts of the articles, and, this time, the terms were grouped into four clusters, as follows. Several (698) articles were identified.

Cluster 1 (red color) includes terms such as industry (refer to wine industry), economy, producer, tourism development, resources, territory, rural area, wine route, attraction, gastronomic tourism, cultural heritage, and tradition; these terms define in fact all the complementary activities and specific products and services related to wine tourism and to the wine producers directly linked to the wine routes;

Cluster 2 (green color) includes terms such as visitors, group, motivation, segmentation, behavior, tasting, visit, attitude, emotion, loyalty, inside;

Cluster 3 (blue color) includes terms that refer to sustainability, hospitality, and sustainable practice;

Cluster 4 (yellow color) includes terms such as visitors, wine tourist, satisfaction, motivation, behavior, intention, wine tasting, wine festivals, and authenticity. These terms practically define wine tourists.

After this stage, we filter the articles by country, respectively, for Romania and Moldova. For Romania, 25 articles from WoS and 26 articles from Scopus were found, and for Moldova, only three articles from Wos and eight from the Scopus database. We also proceeded with the VOSviewer for articles that refer to Romania and Moldova, but the software does not return a significant map.

3.2. Results for Quantitative Analysis Based on Questionnaire (The Horizontal Analysis)

Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient for reliability analysis of items and scales indicates a satisfactory level of overall reliability (0.677) for most items, according to the results from

Table 3.

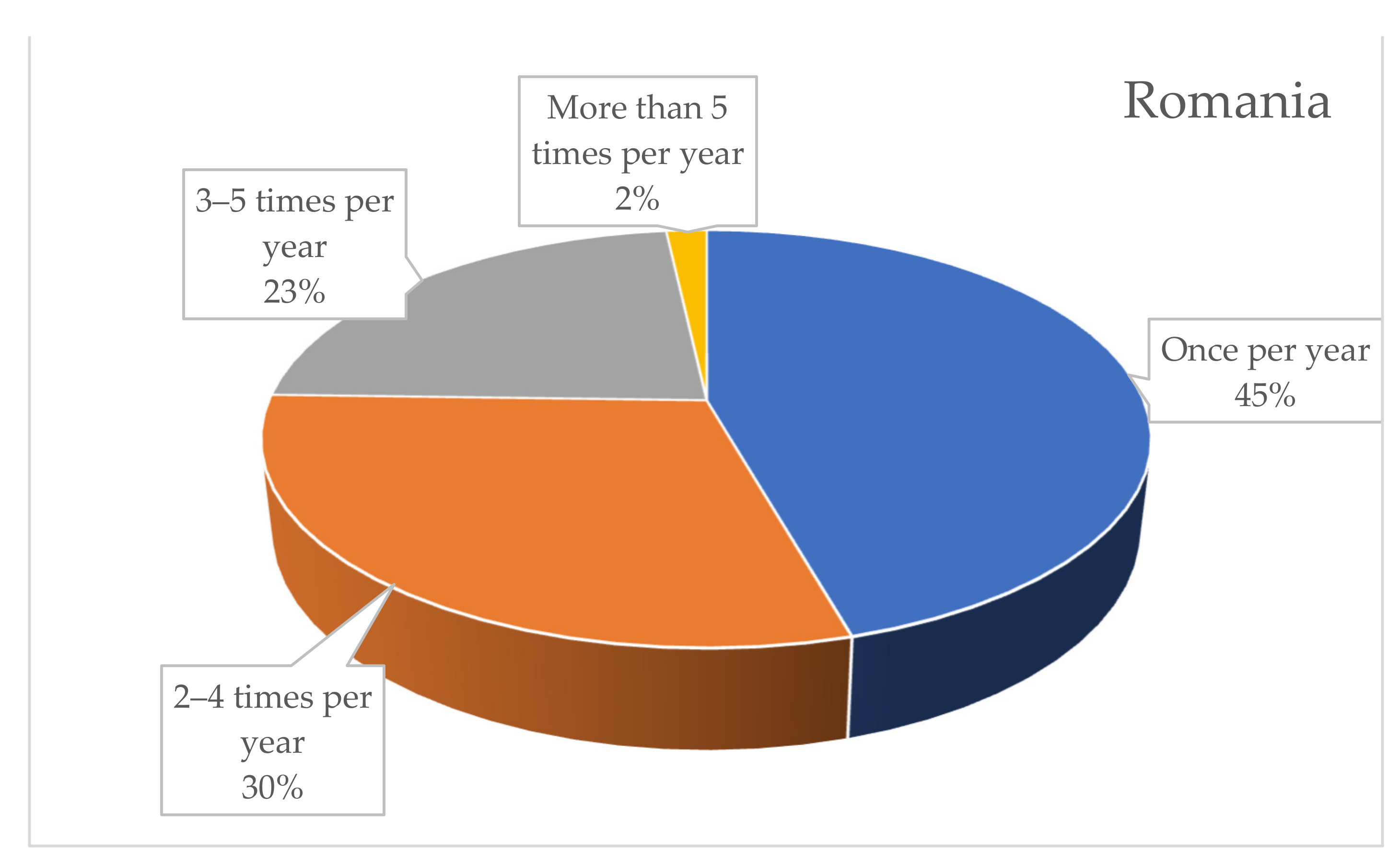

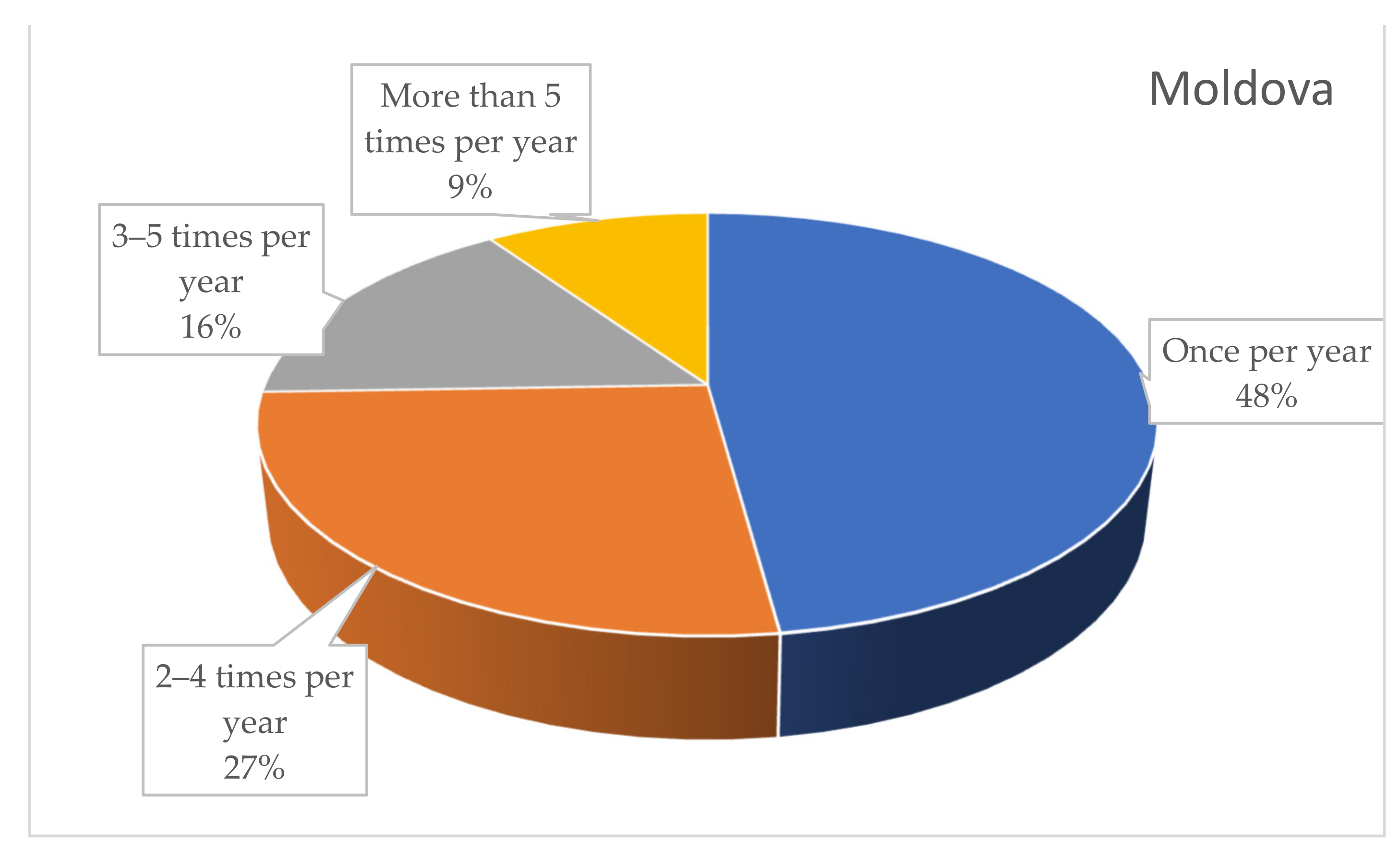

For the frequency with which they travel to the wine regions per year, the distributions are presented in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8. The structure is symmetrical with the exception of more than five times per year; 9% of Moldavian tourists travel more than five times per year, while for Romanian tourists, only 2% travel to wine regions more than five times per year.

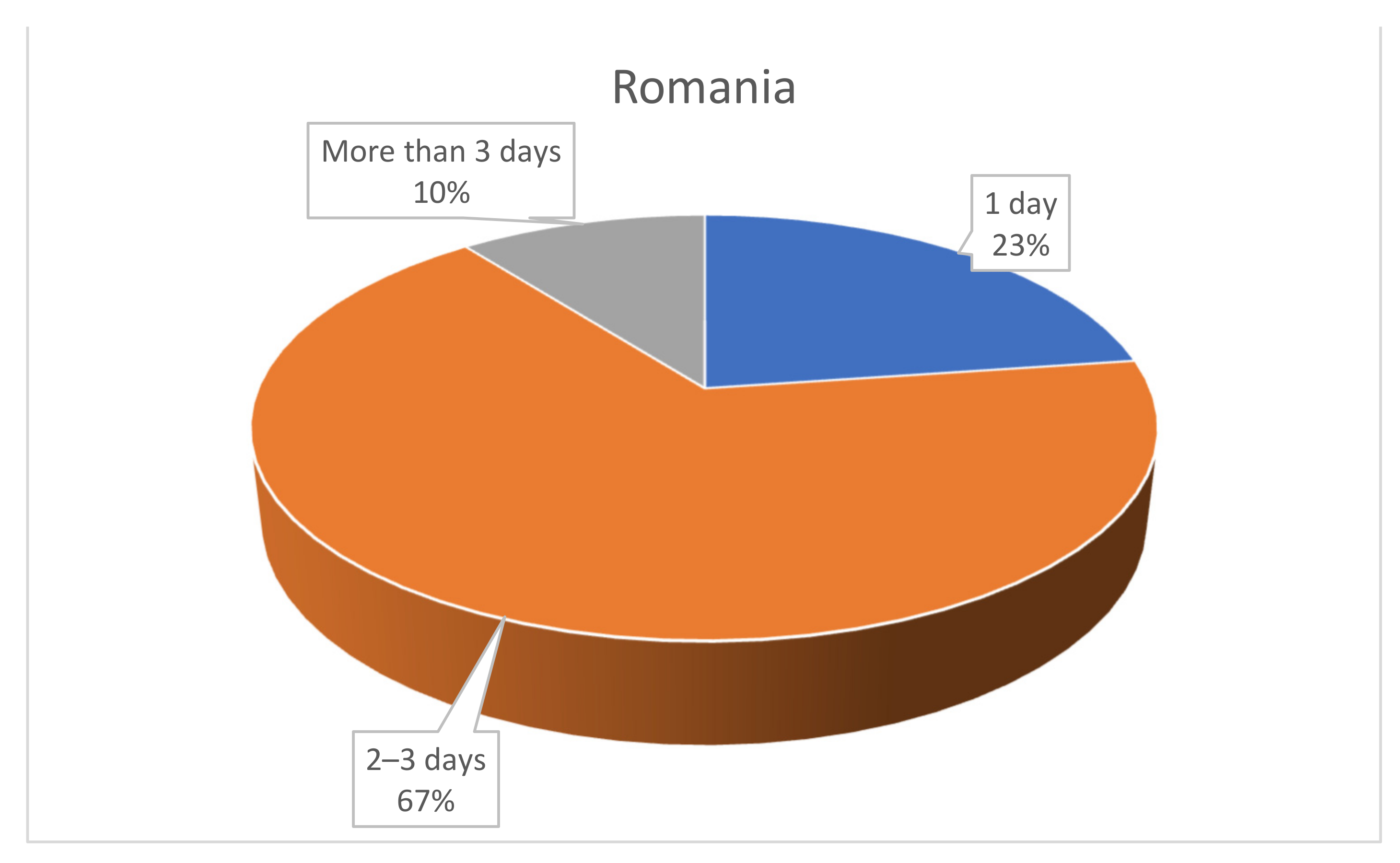

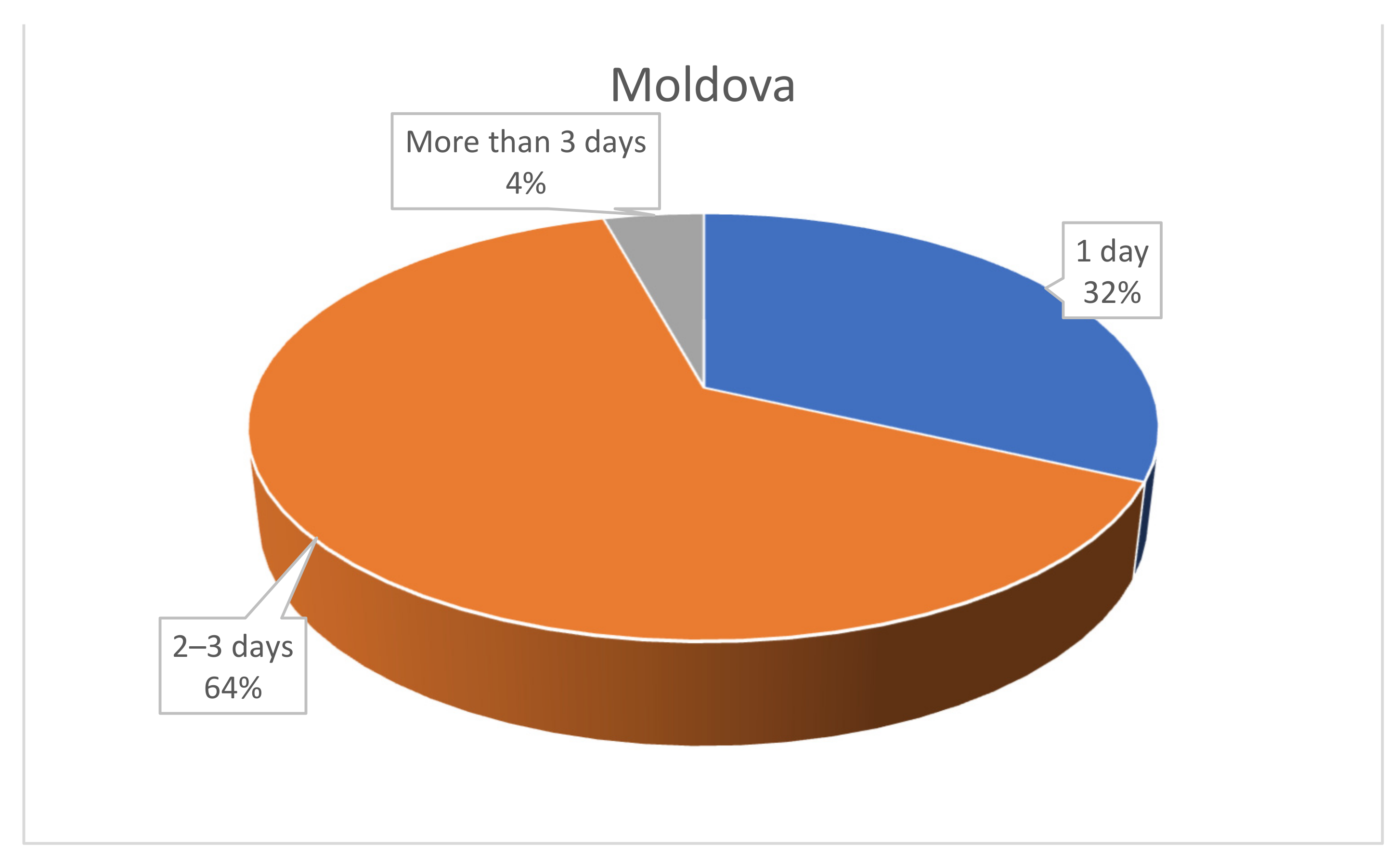

Regarding the average stay, the answer’s structure is presented in

Figure 9 for Romania and

Figure 10 for Moldova. Even the structure is different for Romania and Moldova, with 32% of Moldavian tourists staying 1 day, and only 23% of Romanian tourists and 10% of Romanian compared with only 4% of Moldavian staying more than 3 days for wine tourism, on average both the Romanian and Moldavian tourists stay 2 days (after own calculations based on weighted average).

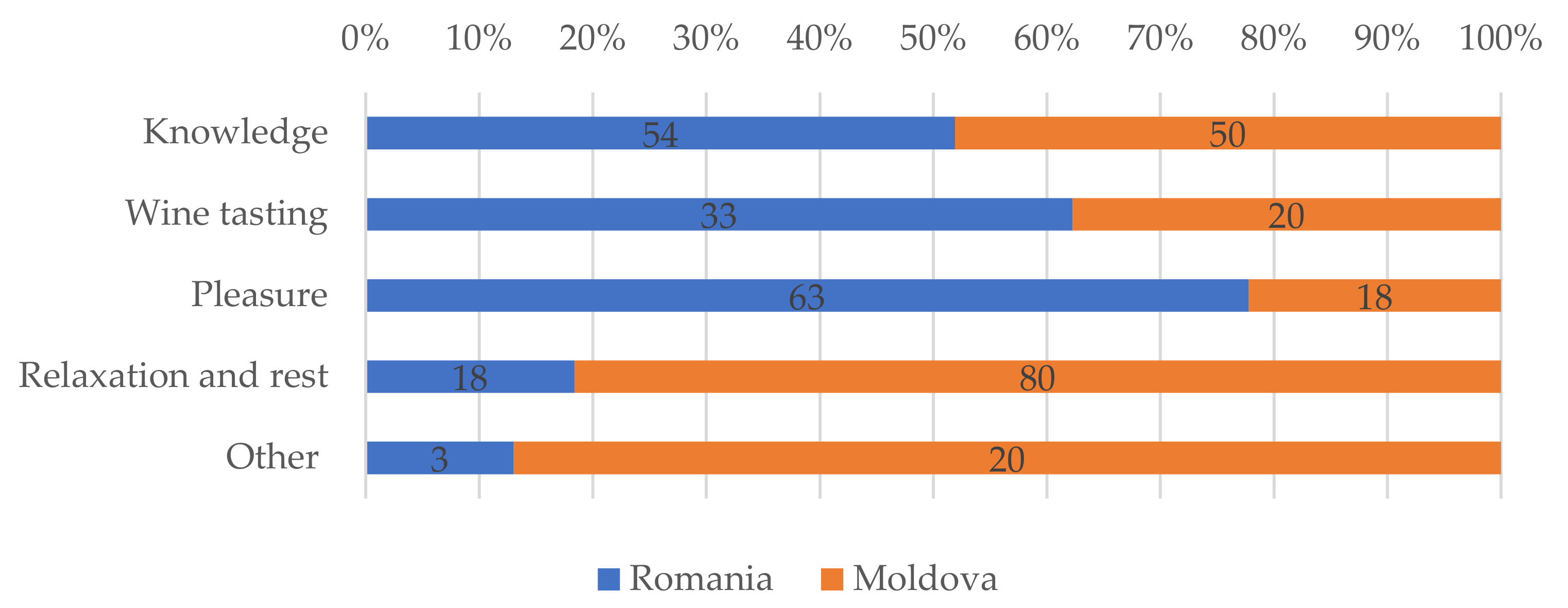

Regarding the motivation for wine tourism, the comparative structure of the answers is presented in

Figure 11. There is clearly a difference between the motivations for wine tourism for the respondents from the two countries. The Romanian wine tourists travel for: pleasure (37%), knowledge (32%), and wine tasting (19%), the last motivation being for relaxation and rest (11%). The Moldavian wine tourists travel for relaxation and rest (42%) and knowledge (27%). For the rest of the motivations, the percentages are equal: 11% for wine tasting, 11% for other motivations, and 10% for pleasure. The motivations, with the exception of knowledge, are opposite for Romania and the Republic of Moldova; Romanian tourists travel for pleasure, and the Moldavians travel to relax and rest.

The most visited Romanian wine cellars are Villa Vinea, Mureș (39%); Avincis, Drăgășani (23%); Clos de Colombes, Constanța (19%); Știrbey, Drăgășani (11%); Rottenburg, Ceptura Dealu Mare (9%); and others (3%). All of these wine cellars are from PGI and/or PDO vineyards with premium wine. The Villa Vinea wine cellar is in the Târnave region of Transylvania, with some of the best white grapes in Romania, producing quality crops and an excellent lot of Pinot Noirs and Fetească Neagră. The AVINCIS wines are an expression of the Drăgășani terroir. Clos de Colombes has a proper dedicated internet page for oenotourism with specific mention of the “clos experience”, which combines food and wine tasting and the advantage of the Black Sea neighborhood. The Știrbei and Rottenburg wine cellars are in the Dealu Mare vineyard.

For Moldova, the most visited wine cellars are Cricova (46%), Mileștii Mici (27%), both from the Codru PGI region, Purcari (19%) from Ștefan—Vodă PGI wine producers—and others wine cellars from the rest of the Moldavian regions, such as Valul lui Traian and/or Divine (9%). It can be observed that the most visited wine cellars are from well-known wine brands, such as Cricova, Purcari, and Bostavan, with the following type of wine: Cabernet Sauvignon, Chardonnay, Merlot, Riesling de Rhein, and Sauvignon Blanc. The predominant varieties in Ștefan—Vodă PGI are Cabernet Sauvignon, Chardonnay, Merlot, Sauvignon Blanc, Pinot Gris, Rara Neagră, and Malbec.

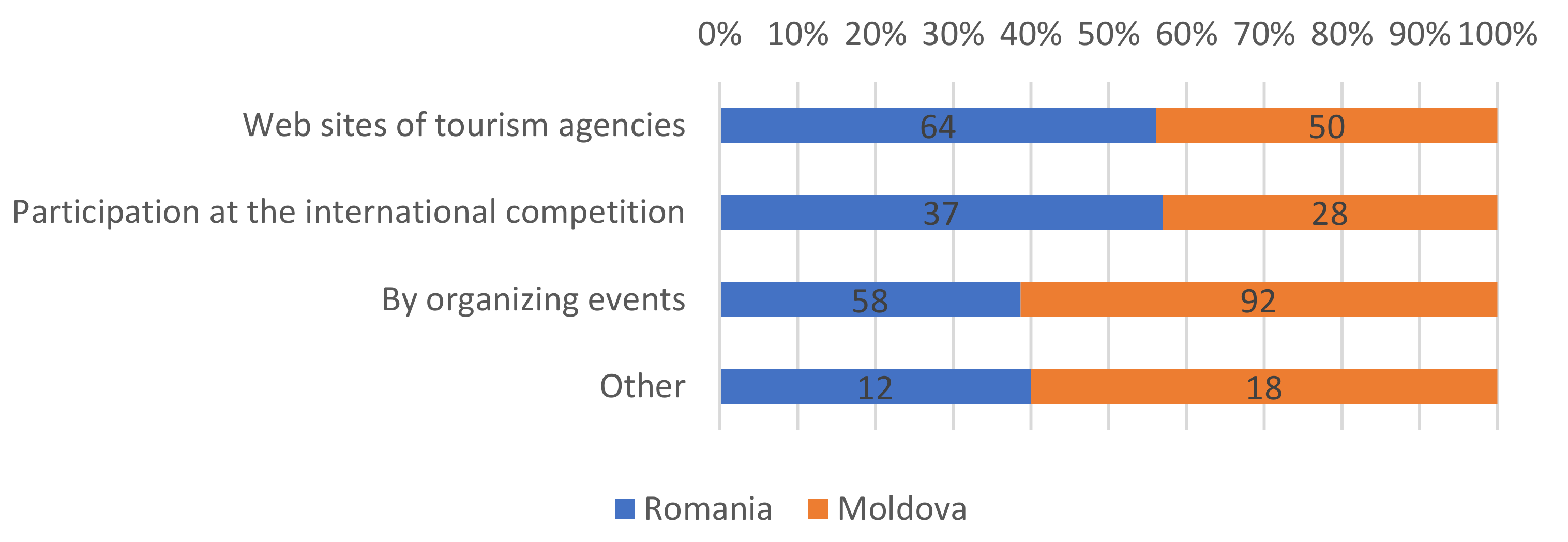

Regarding the opinion referring to the type and/or place of promotion of a wine region, the distribution of the answers is presented in

Figure 12. So, the Romanian tourists first suggest the websites of tourism agencies (37%), organizing dedicated events (33%), participation in international competitions (21%), and other (7%). The Moldavian tourists first suggest the organization of special events (49%), followed by the websites of tourism agencies (27%), participation in international competitions (15%), and other (10%). It is thus observed that, also for promotion, the opinions of Romanian and Moldavian tourists are quite the opposite regarding the first two suggestions.

The elements appreciated by the Romanian tourists at a wine cellar are the possibility of an integrated service (46%), accommodation–food–entertainment (32%), rural region (12%), and wine quality (11%). For the Moldavian tourists, these elements are quite different and are as follows: accommodation–food–entertainment (48%), the possibility of an integrated service (30%), wine quality (12%), and interaction with local people (11%).

The preferred accommodation for wine tourism in Romania are rural guest houses (28%), apartments and rooms for rent (26%), hotels (23%), tourist villas (19%), and bungalows (4%). The Moldavian tourists prefer tourist villas (29%), apartments and rooms for rent (19%), no accommodation needed (16%), rural guest houses (15%), hotels (14%), and bungalows (7%).

3.3. Results for Quantitative Analysis Based on Questionnaire (The Vertical Analysis)

According to the results of the horizontal analysis presented in

Section 3.2. there are differences between Romania and the Republic of Moldova. Therefore, we applied statistical tests to know if there are statistically significant differences between wine tourists from these countries. In

Table 4, the results are presented according to the chi-square bivariate test with the statistical hypothesis indicated in the table. H

0 = There are no statistically significant differences between the Romanian and Moldavian tourists regarding all the aspects mention in the

Table 4.

According to the results in

Table 4, we can conclude that there are statistically significant differences between wine tourists from Romania and the Republic of Moldova for overall motivation for travel, and when we split this variable into specific motivations (according to the specific responses from the questionnaire) and separated dichotomous variables, we find that: (i) both the Romanian and Moldavian tourists travel for knowledge (

p > 0.05); (ii) there are statistical differences between them referring to the pleasure and the results of chi-square test, confirming the horizontal analysis that Romanian tourists travel for pleasure (

p < 0.05), and (iii) referring to the relaxation and rest and the results of chi-square test, confirming the horizontal analysis that Moldavian tourists are motivated by relaxation and rest (

p < 0.05).

There are no statistically significant differences between the Romanian and Moldavian regarding the frequency of travel, length of stay, and the perception of the type and/or place of promotion of a wine region (p > 0.05).

There are statistically significant differences between Romanians and Moldavians regarding the visited cell wine, the elements appreciated by tourists at a wine cellar, and the preferred type of accommodation. All of these results confirm the results of the horizontal analysis that indicate the differences between the absolute and relative frequencies of the answers.

Due to the above-mentioned results, we applied statistical tests to analyze if inside each sample of wine tourists (Romanian/Moldavian), there are statistically significant differences according to the socio-demographic characteristics of the tourists from

Table 2. The results are structured in

Table 5.

According to the results from

Table 5, there are statistical differences inside each sample as shown: (a) for Romania, only according to the occupational status for relaxations and rest as motivation for wine tourism and length of stay; (b) for the Republic of Moldova, only according to gender for the overall motivation for wine tourism, knowledge as motivation for travel, and the perception of type or place for promoting wine tourism in Moldova.

To better understand the motivation for travel for wine tourism in Romania and the Republic of Moldova, we applied the linear regression model with the Enter method and collinearity diagnosis for each sample. We conducted this twice, as shown in the following:

Model 1 with overall motivation as a dependent variable and socio-demographics characteristics of tourists as independents variables;

Model 2 with overall motivation as a dependent variable and specific variables for wine tourism as independent variables.

For both samples and models of tourists, the model summary (

Table 6) indicates a good R square coefficient (>0.800) and a significant statistic model according to ANOVA results (

p < 0.05) from

Table 7.

The regression coefficients are presented in

Table 8 for the socio-demographic variables as independent variables from Model 1 and for the specific travel for wine tourism from Model 2. According to the results of the collinearity statistics, there are two variables for Romania for Model 1 with a value outside of a [1.00–10.00] interval for age and education. For Model 2, only one variable for the Republic of Moldova is collinear, the dependent variable, the appreciated elements of a visited wine cellar.

According to the values of the standardized coefficients Beta, the most important variables for the overall motivations of Romanian and Moldavian tourists in Model 1, are for Romania: education (0.500), occupational status (0.496), and for Moldova: age (0.726), gender (0.659), monthly income (0.498), and education (0.157);

For Model 2, for Romanian tourists, the key factors are linked to the type of promotion of a wine region (0.436), travel frequency (0.301), and the length of stay (0.242). For Moldavian ones, in first place remains the type of promotion of a wine region (0.436), followed by the accommodation (0.329), travel frequency (0.218), and the length of stay (0.151).

Therefore, for

Model 1, the regression coefficients for Romania and the Republic of Moldova are ((Equations (1) and (2)), with bold text showing statistically significant variables (

p < 0.1) for the regression models:

So, increasing education by one unit (from vocational school to university), the motivation moves from knowledge to relaxation and rest for Romanian tourists, with 0.801. Additionally, increasing the occupational status by 1 unit leads to an increase in motivation, with 0.654 in the same direction, respectively, from knowledge to pleasure and/or relaxation and rest. For the profile of Romanian wine tourists, education and occupational status are the most important characteristics of their profile.

For the Moldavian tourists, the profile of wine tourists is more detailed, and more specifically: increasing with 1 unit of gender (practically from female to male according to the SPSS software codification of variables), the overall motivation increases by 2.150. When increasing age by 1 unit, the overall motivation increases by 1.115, practically from knowledge to relaxation and rest. It is evident that, for Moldavian tourists, there are the most important variables for the profile of wine tourists, but it is completed with an educational level.

For

Model 2, the regression coefficients for Romania and the Republic of Moldova are ((Equations (3) and (4) with bold text for statistically significant variables (

p < 0.1) for regression models):

For Romanian tourists, the results from Model 2 indicate that by increasing travel frequencies by one unit, the overall motivation increases by 0.384; by increasing the length of stays by one unit, the overall motivation increases by 0.462, and increasing the type of promotion by one unit for the wine region, the overall motivation increases by0.477.

For Moldavian tourists, the results from Model 2 indicate that by increasing travel frequencies by one unit, the overall motivation increases by 0.309; increasing the length of stays by one unit, the overall motivation increases by 0.403; increasing the type of promotion suggested by one unit for wine region the overall motivation increase by 0.736, and increasing the type of preferred accommodation by one unit, the overall motivation increases by 0.297.

4. Discussion

Our results could be considered a representative one, taking into consideration the education of the respondents, 34% from Romania and 54% from Moldova are tourists that have university degrees, which confirms the results from the Tendencies Enotur report [

82]. Additionally, the distribution of respondents according to their age is close to the sample of the cited report, with an increasing interest of young tourists in wine tourism in Romania and the Republic of Moldova.

The present results validate the international one regarding the preferred type of accommodation for wine tourists [

82], respectively, villas, bungalows, and apartments. The resulting distribution of accommodation is relatively equal to all types of accommodation and close to the specific accommodation of rural areas which have been in high demand by tourists during the pandemic [

6,

18,

83,

84] and practically emphasizes that wine tourism sustains the rural development and is a very good strategic tool for sustainable management. Both countries have the potential for rural tourism and could use wine tourism as an instrument to promote an integrative tourism service and product. Therefore, tourism development in general, and wine tourism, in particular, has received increasing recognition as a tool for encouraging regional and national economies [

85].

Regarding the length of stay for wine tourism, our results confirm the results from Tendencies Enotur [

82] report, an important percent of Romanian and Moldavian tourists stay only 2 or 3 days for wine tourism (67% for Romania and 64% for Moldova). Only 32% of Moldavians and 23% of Romanians prefer trips without spending the night in a wine region. These results are in line with the allocated budget for wine tourism, Romanian but especially the Moldavian tourists being practically from medium to low-income countries dedicated to leisure and relaxing activities.

The motivations for wine tourism of Romanian and Moldavian tourists are quite different. Romanian tourists visit wine regions for pleasure (similar to French visitors according to Atout France [

86]) and Moldavian tourists for relaxation and rest predominantly, but both Romanian and Moldavian tourists for knowledge [

19,

87]. They mention wine tasting [

88] as one of the main motivations to visit wine regions, and learning about wine is one of the specific motivations from Bruwer [

89] to visit the wine route. These results confirm the research conducted by Tendencies Enotur [

82] that indicates that the Italian, Spanish, French, and American tourists have, as the main motivations for wine tourism, visiting the winery (and therefore the knowledge), the quality of the region, discovering the region, and wine tasting. The present research emphasizes and confirms the significant differences in the wine tourism motivations and values remarked by the Tendencies Enotur report [

82]: Italy and France have a more global outlook on wine tourism as part of the countryside, and Spain and the USA appreciate the tangible and concrete relationship with the wine more [

82]. Motivations are key to modeling the event to satisfy visitors [

22], and they must be identified first before designing a destination management strategy.

We can conclude that, according to Hall and Macionis [

11], for the segmentation of wine tourists, Romanian tourists are “wine lovers”, the main motivation being pleasure, and the Moldavian tourists are “wine interested” [

1], according to their main motivation for relaxation and rest [

20] near to knowledge and wine tasting.

Based on the present results of the qualitative and quantitative analyses and starting with the new domestic wine tourism from two East European countries, both countries being producers and exporters from the “Old World” of wine, we suggest some recommendations for the development of wine tourism. Our first recommendation is to increase the demand for wine tourism worldwide [

90] by using wine tourism as an instrument for direct sales [

91]. Additionally, it is important for vineyard and tourism agencies to reorient wine tourism from the “service economy” to the “experience economy” [

6,

22,

24,

25,

92,

93,

94] together with highlighting tourist attractions and animating and offering authentic national specificities In wine tourism, due to the links to cultural and local aspects of the vineyards region, especially in rural areas, it is important to diversify the tourist products and offer themed tourist products in the field of wine tourism. Increasing the role of innovation and information technology, a decisive factor in the competitiveness of the tourism industry could be conducive to increasing worldwide competition and configure Europe as the main tourist destination, with new emerging destinations, such as those in Romania and Moldova. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, but especially after the end of this period, increasing competition in the quality of tourist services and the use of the Q symbol/label was observed [

6,

82], and strategies could be used to promote wine tourism in studied countries. More, the internet, and especially the network [

85], could be a helpful solution for wine producers and tourism agencies that promote wine tourism. For the promotion of wine tourism, we recommend the approach used by Correira and Brito [

95] for wine tourism as a territorial experience to emphasize the intangible components (tradition, authenticity, environment, culture, and interactions with locals) together with tangible components (wine producers, cellars, restaurants, landscapes, and touristic actors).

Considering gastronomy as the basic element of wine tourism, such as in Spain, where gastronomic routes have been created that include wine routes [

6,

69,

95,

96,

97], these gastronomic routes can be created based on the influence of multiculturalism in Romania and Moldova (Hungarian, Turkish, Russian, Serbian, Austrian, German, etc.). By using the common effort to promote the cultural and local heritage of Romania and Moldova through the cultural–touristic route ”Voievod Ștefan cel Mare și Sfânt” (Voivode Stephen the Great and Saint), these countries must develop a national strategy for wine tourism similar to Australia, which was a pioneer in this direction [

1]. Building a strategy by inserting wine tourism into part of the wine value chain between producers and consumers (B2C) or/and producers and traders (B2B) based on the model of Anastasiadis & Alebaki [

13], Romania and Moldova must promote and integrate the PDO and PGI products in tourism offers because of tradition and the specialization of high-quality products [

6].

Wine is one of those goods that builds its brand on its geographical origin [

98]. Therefore, another recommendation for Romania and the Republic of Moldova, based on the present research results, is to develop and intensively promote the initiative of the cultural–touristic route “Voievod Ștefan cel Mare și Sfânt” (Voivode Stephen the Great and Saint) [

99] as a common effort to promote the common historical elements of these countries. This route includes 24 touristic objectives from Romania and 30 from the Republic of Moldova.

Wine tourism offers a lot of opportunities for local development [

76], especially for regions with vineyards, UNESCO heritage, multiculturalism, and landscapes [

4], being a sustainable tool for tourism. A good strategy for promoting wine tourism is combining it with culinary tourism [

20] by slow food [

56], the combination of food and drink being the base of tourism packages. Today, in the tourism industry, the knowledge of sensory dimensions of a tourist’s experience is relevant for the improvement of tourism destinations [

22]. The present research results allowed, based on the new tourist patterns, the development of strategies and policies for destination management in Romania and Moldova related to promotional activities and destination branding development. Understanding the relationship between the experience dimensions of satisfaction–destination loyalty could help to better develop wine destinations [

100].

Wine tourism is complex due to (1) the nature of the visited vineyards, (2) the culture of the visited UNESCO and/or historical and cultural heritage of the regions, and (3) local/regional gastronomy. Both the wine and tourism industries rely on regional branding for market leverage and promotion [

85], which are compatible with predominantly rural areas looking for sustainable development [

95]. Based on the present results, and according to Boatto et al. [

101], both the Romanian and Moldavian wine markets (and wine tourism, too) are between the second and third stage of the life circle, winery recognition, and regional prominence [

101], with an important emphasis on the rural component of them.

5. Conclusions

Based on the present research results, we can conclude that the main tools to promote wine tourism in Romania and Moldova:

Applying a new communication model based on social networks [

102] despite traditional communication methods [

82,

103];

E-marketing [

104] and events [

86], E-WOM [

6];

Using virtual reality experience for a memorable, emotional, and immersive experience [

105].

Both Romania and Moldova could follow the example of Australia, a New World wine producer that recommends increasing efforts to overcome the cottage industry mentality of wine tourism and creating an overall tourist experience [

25,

94] rather than a cellar door experience [

22] and developing infrastructure that is suitable for luxury offerings [

35]. In a single word, the 4E strategy: entertainment, education, esthetics, and escapist. For Romania and Moldova, wine tourism can become a reference in sustainable rural tourism due to its focus on economic, environmental, and social sustainability [

4,

6,

53,

83]. The top ten countries in the tourism industry, for example, Spain, act according to the recent changes in travel due to the COVID-19 pandemic and create new destinations, generating complementary routes for tourists [

6]. Therefore, Romania and Moldova must act in the same direction because the tourism sector is changing its profile [

6].

Determining factors in the relationship of wine tourism are the diversity and possibility of an integrated service based on the following elements: wine tasting, the environment, cultural activities, recreation, and food [

6]. Taking France as an example [

86], Romania and Moldova could integrate services, such as scenic wine routes with UNESCO world heritage sites, walking and biking, trade exhibitions, and consumer fairs. Therefore, wine tourism offers economic and social benefits thanks to sensorial experiences [

92,

93,

94]. Due to the fact that over-tourism is a real problem in large urban centers, wine tourism can become a powerful alternative, providing a new perspective and enlarging and diversifying the touristic offerings in large destinations [

14].

Both Romania and Moldova must promote the uniqueness of certain areas and unify marketing synergies [

6]. More, wine tourism in rural areas that provide a wide range of complementary activities throughout the year means that it is possible to reduce the seasonality and create more stable jobs [

6]. Tourists seeking nature during the pandemic can help mitigate the socioeconomic gap in rural areas and provide endogenous development [

6].

As is known and applied in many aspects of the world industry, wine tourism strictly requires the existence of a body that effectively unites the main government departments, especially those with attributions in the field of finance, land use, environmental protection, transport, and tourism, in the joint effort to develop the sector [

106]. Additionally, continuing from the above-mentioned recommendations for Romania and Moldova, an integrated approach [

13] must be applied to wine tourism in these countries; wine tourism is a sub-system of the tourism sector with both tangible and intangible components, and it is a complex resource (human, industrial, environmental, and institutional). Wine tourism is located at the intersection of agribusiness-oriented wine production and hedonic service/experience-oriented tourism activities [

100].

The limits of this research refer to (1) the survey’s methodology due to the COVID-19 pandemic, (2) the geographic area of research performed, (3) the cultural similarities of the Romanian and Moldavian tourists, and (4) the good commercial changes for wine between Romania and the Republic of Moldova and the influence of already tested wine brands.

For future research in the wine tourism field, the authors intend to extend this comparison and include other European countries to analyze the efficiency of the different communication systems used by the old and new world wine destinations and to include samples of other nationalities who visited Romania and Moldova.