The Effect of a Virtual Reality-Based Intervention Program on Cognition in Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Randomized Control Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

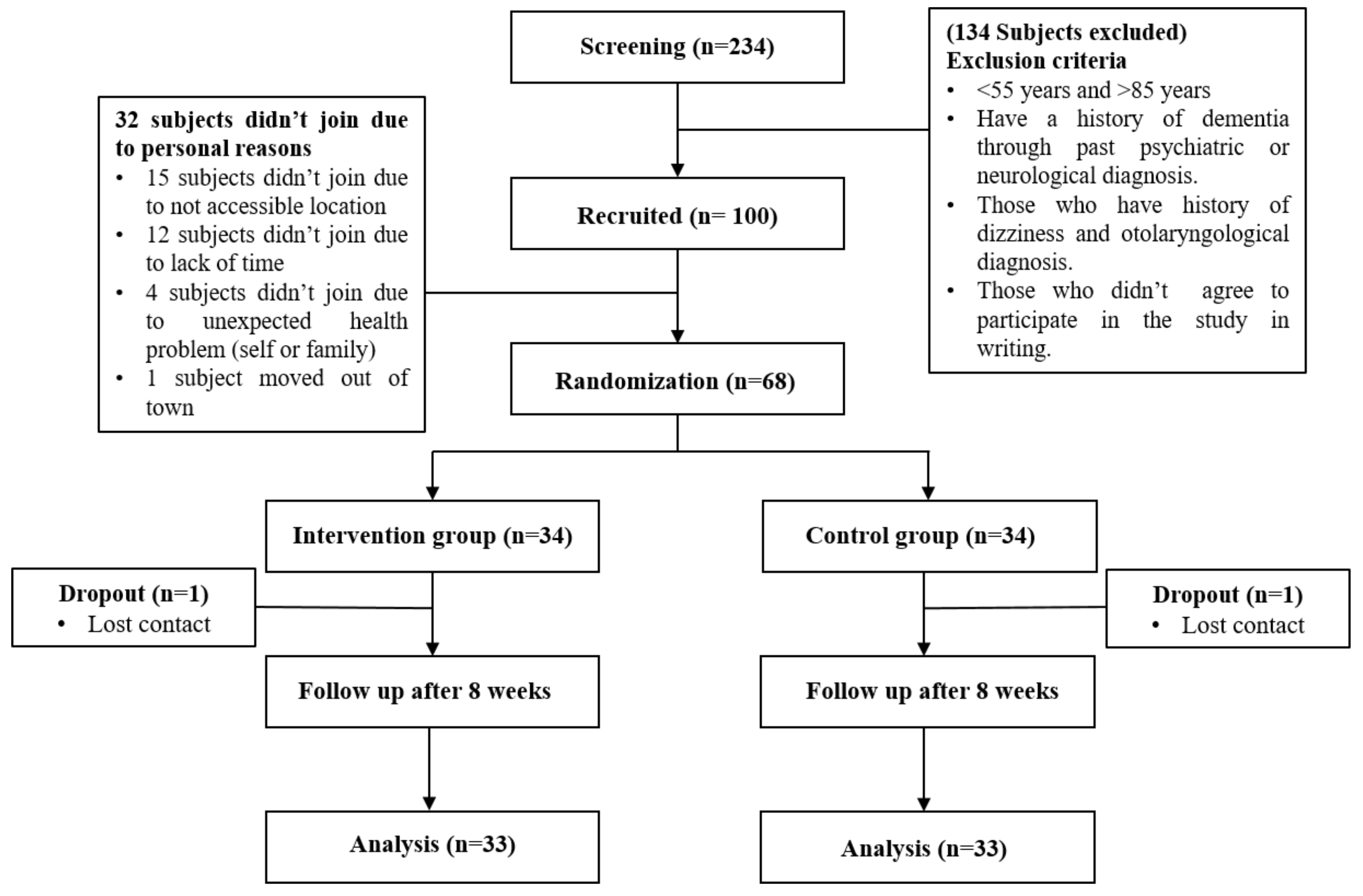

2.1. Subjects

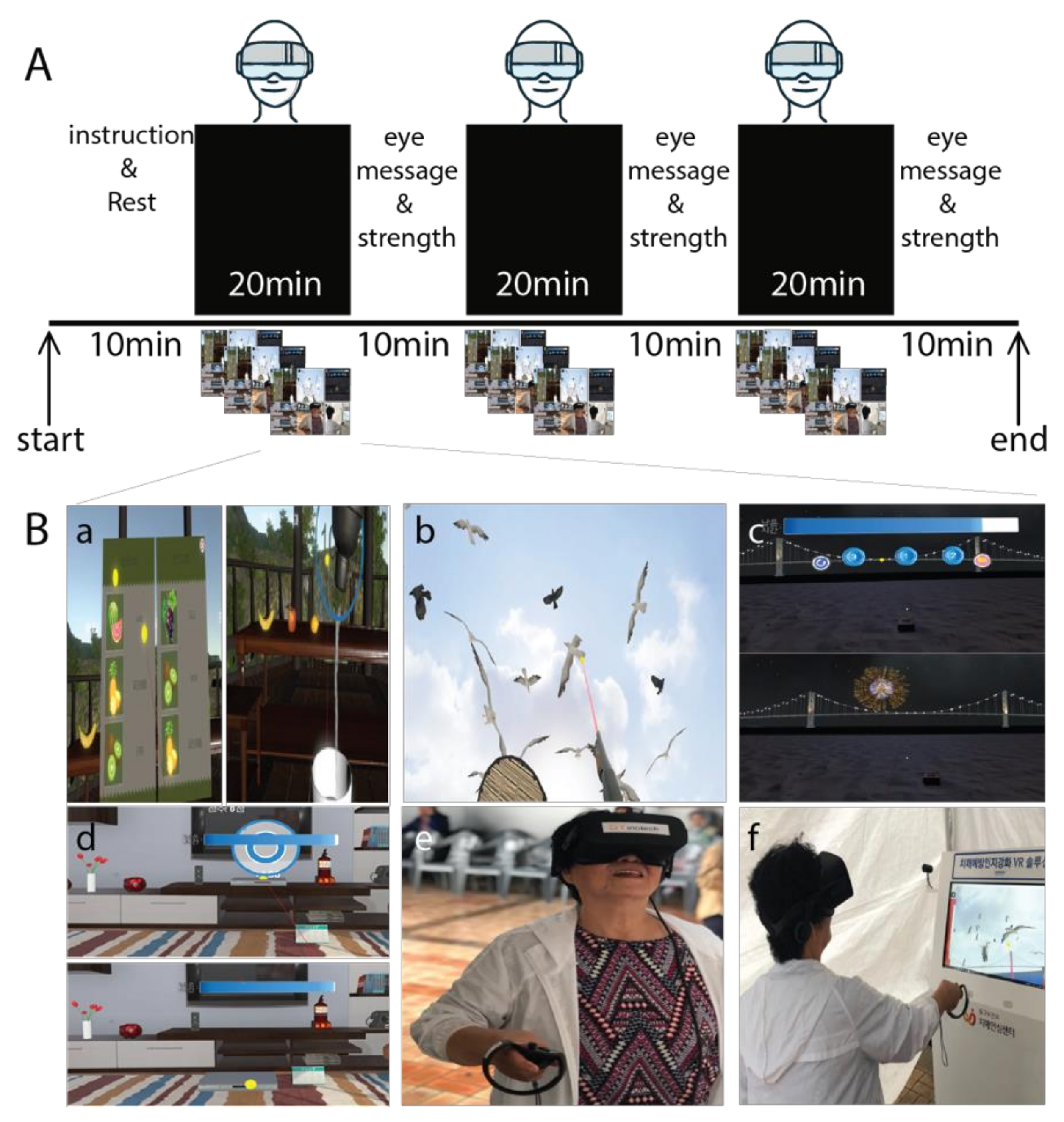

2.2. Intervention

2.3. Cognitive Function

2.4. EEG Recording and Data Acquisition

2.5. Physical Function

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Result

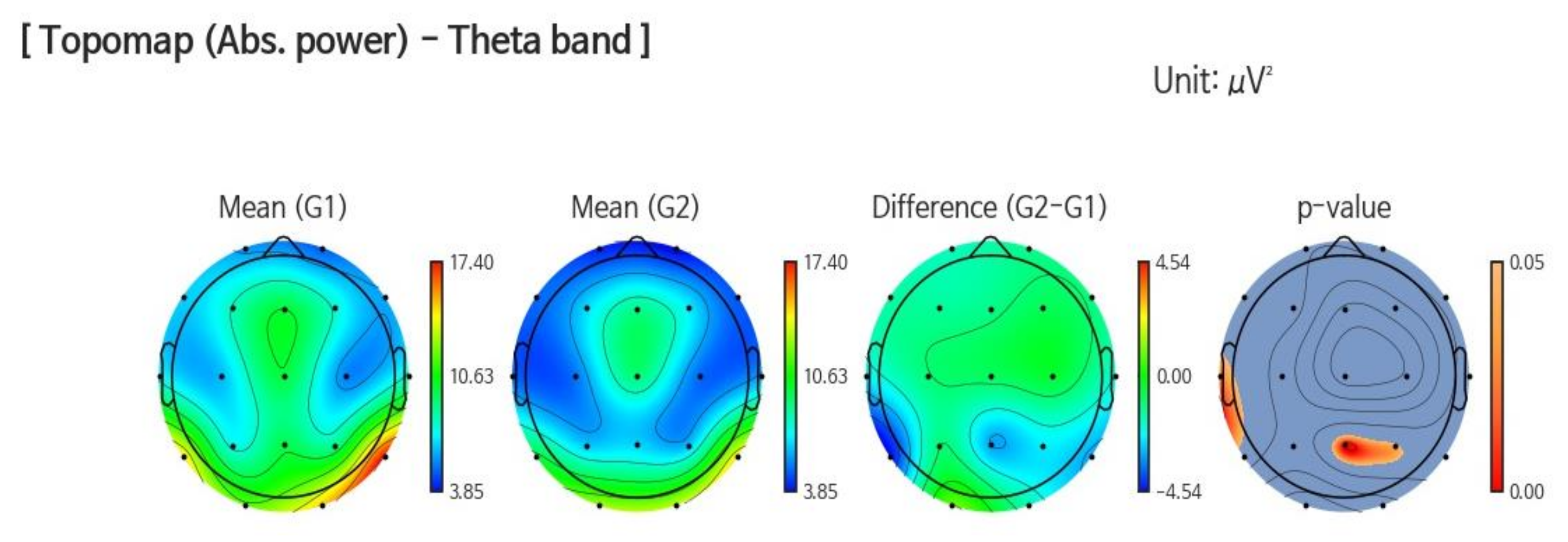

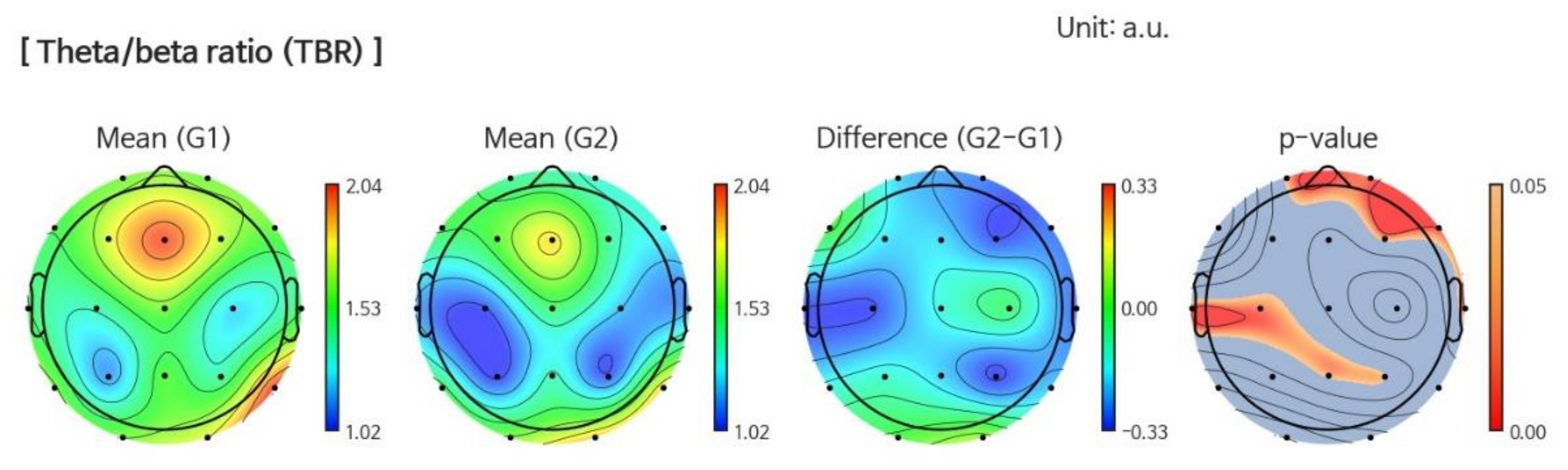

3.1. EEG

3.1.1. Band Power

3.1.2. Power Ratio

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK). Dementia. In Dementia: A NICE-SCIE Guideline on Supporting People With Dementia and Their Carers in Health and Social Care; British Psychological Society: Lester, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Dementia. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia (accessed on 26 February 2020).

- Livingston, G.; Sommerlad, A.; Orgeta, V.; Costafreda, S.G.; Huntley, J.; Ames, D.; Ballard, C.; Banerjee, S.; Burns, A.; Cohen-Mansfield, J. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet 2017, 390, 2673–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Cunha, N.M.; Georgousopoulou, E.N.; Dadigamuwage, L.; Kellett, J.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; Thomas, J.; McKune, A.J.; Mellor, D.D.; Naumovski, N. Effect of long-term nutraceutical and dietary supplement use on cognition in the elderly: A 10-year systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Br. J. Nutr. 2018, 119, 280–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, M.S.; DeKosky, S.T.; Dickson, D.; Dubois, B.; Feldman, H.H.; Fox, N.C.; Gamst, A.; Holtzman, D.M.; Jagust, W.J.; Petersen, R.C. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2011, 7, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, K.; Mukadam, N.; Petersen, I.; Cooper, C. Mild cognitive impairment and progression to dementia in people with diabetes, prediabetes and metabolic syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2018, 53, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, S.; Reisberg, B.; Zaudig, M.; Petersen, R.C.; Ritchie, K.; Broich, K.; Belleville, S.; Brodaty, H.; Bennett, D.; Chertkow, H. Mild cognitive impairment. Lancet 2006, 367, 1262–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daviglus, M.L.; Bell, C.C.; Berrettini, W.; Bowen, P.E.; Connolly, E.S.; Cox, N.J.; Dunbar-Jacob, J.M.; Granieri, E.C.; Hunt, G.; McGarry, K. National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science Conference statement: Preventing Alzheimer disease and cognitive decline. Ann. Intern. Med. 2010, 153, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.; Park, J.H.; Na, H.R.; Hiroyuki, S.; Kim, G.M.; Jung, M.K.; Kim, W.K.; Park, K.W. Combined Intervention of Physical Activity, Aerobic Exercise, and Cognitive Exercise Intervention to Prevent Cognitive Decline for Patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Study. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucchella, C.; Sinforiani, E.; Tamburin, S.; Federico, A.; Mantovani, E.; Bernini, S.; Casale, R.; Bartolo, M. The multidisciplinary approach to Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. A narrative review of non-pharmacological treatment. Front. Neurol. 2018, 9, 1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Htut, T.Z.C.; Hiengkaew, V.; Jalayondeja, C.; Vongsirinavarat, M. Effects of physical, virtual reality-based, and brain exercise on physical, cognition, and preference in older persons: A randomized controlled trial. Eur. Rev. Aging Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Optale, G.; Urgesi, C.; Busato, V.; Marin, S.; Piron, L.; Priftis, K.; Gamberini, L.; Capodieci, S.; Bordin, A. Controlling memory impairment in elderly adults using virtual reality memory training: A randomized controlled pilot study. Neurorehabilit. Neural Repair 2010, 24, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baus, O.; Bouchard, S. Moving from Virtual Reality Exposure-Based Therapy to Augmented Reality Exposure-Based Therapy: A Review. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, A.; Wall, K.J.; Thangavelu, K.; Craven, L.; Ward, E.; Dissanayaka, N.N. A systematic review of the use of virtual reality and its effects on cognition in individuals with neurocognitive disorders. Alzheimer’s Dement. Transl. Res. Clin. Interv. 2019, 5, 834–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manera, V.; Chapoulie, E.; Bourgeois, J.; Guerchouche, R.; David, R.; Ondrej, J.; Drettakis, G.; Robert, P. A feasibility study with image-based rendered virtual reality in patients with mild cognitive impairment and dementia. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151487. [Google Scholar]

- Gatica-Rojas, V.; Méndez-Rebolledo, G. Virtual reality interface devices in the reorganization of neural networks in the brain of patients with neurological diseases. Neural Regen. Res. 2014, 9, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Betances, R.I.; Jiménez-Mixco, V.; Arredondo, M.T.; Cabrera-Umpiérrez, M.F. Using virtual reality for cognitive training of the elderly. Am. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Other Demen. 2015, 30, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, A.S.; Kim, G.J. A SWOT analysis of the field of virtual reality rehabilitation and therapy. Presence Teleoperators Virtual Environ. 2005, 14, 119–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, O.; Pang, Y.; Kim, J.-H. The effectiveness of virtual reality for people with mild cognitive impairment or dementia: A meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zając-Lamparska, L.; Wiłkość-Dębczyńska, M.; Wojciechowski, A.; Podhorecka, M.; Polak-Szabela, A.; Warchoł, Ł.; Kędziora-Kornatowska, K.; Araszkiewicz, A.; Izdebski, P. Effects of virtual reality-based cognitive training in older adults living without and with mild dementia: A pretest–posttest design pilot study. BMC Res. Notes 2019, 12, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weniger, G.; Ruhleder, M.; Lange, C.; Wolf, S.; Irle, E. Egocentric and allocentric memory as assessed by virtual reality in individuals with amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Neuropsychologia 2011, 49, 518–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayma, M.; Tuijt, R.; Cooper, C.; Walters, K. Are We There Yet? Immersive Virtual Reality to Improve Cognitive Function in Dementia and Mild Cognitive Impairment. Gerontologist 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Betances, R.I.; Arredondo Waldmeyer, M.T.; Fico, G.; Cabrera-Umpiérrez, M.F. A succinct overview of virtual reality technology use in Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2015, 7, 80. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Van der Hiele, K.; Vein, A.; Reijntjes, R.; Westendorp, R.; Bollen, E.; Van Buchem, M.; Van Dijk, J.; Middelkoop, H. EEG correlates in the spectrum of cognitive decline. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2007, 118, 1931–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, M.J.; Lacritz, L.; Hynan, L.; Barnard, H.; Allen, G.; Deschner, M.; Weiner, M.; Cullum, C. A total score for the CERAD neuropsychological battery. Neurology 2005, 65, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.H.; Jhoo, J.H.; Park, J.H.; Kim, J.L.; Ryu, S.H.; Moon, S.W.; Choo, I.H.; Lee, D.W.; Yoon, J.C.; Do, Y.J. Korean version of mini mental status examination for dementia screening and its’ short form. Psychiatry Investig. 2010, 7, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makizako, H.; Shimada, H.; Park, H.; Doi, T.; Yoshida, D.; Uemura, K.; Tsutsumimoto, K.; Suzuki, T. Evaluation of multidimensional neurocognitive function using a tablet personal computer: Test–retest reliability and validity in community-dwelling older adults. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2013, 13, 860–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klem, G.H.; Lüders, H.O.; Jasper, H.; Elger, C. The ten-twenty electrode system of the International Federation. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1999, 52, 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Prichep, L.; John, E.; Ferris, S.; Rausch, L.; Fang, Z.; Cancro, R.; Torossian, C.; Reisberg, B. Prediction of longitudinal cognitive decline in normal elderly with subjective complaints using electrophysiological imaging. Neurobiol. Aging 2006, 27, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Moguel, S.M.; Alatorre-Cruz, G.C.; Silva-Pereyra, J.; González-Salinas, S.; Sanchez-Lopez, J.; Otero-Ojeda, G.A.; Fernández, T. Two Different Populations within the Healthy Elderly: Lack of Conflict Detection in Those at Risk of Cognitive Decline. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2018, 11, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Son, D.; De Blasio, F.M.; Fogarty, J.S.; Angelidis, A.; Barry, R.J.; Putman, P. Frontal EEG theta/beta ratio during mind wandering episodes. Biol. Psychol. 2019, 140, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle, H.; Traynor, V.; Solowij, N. Computerized and virtual reality cognitive training for individuals at high risk of cognitive decline: Systematic review of the literature. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2015, 23, 335–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.-Y.; Chen, I.-H.; Lin, Y.-J.; Chen, Y.; Hsu, W.-C. Effects of Virtual Reality-Based Physical and Cognitive Training on Executive Function and Dual-Task Gait Performance in Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Randomized Control Trial. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2019, 11, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahurin, R.K.; Velligan, D.I.; Hazleton, B.; Mark Davis, J.; Eckert, S.; Miller, A.L. Trail making test errors and executive function in schizophrenia and depression. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2006, 20, 271–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Cubillo, I.; Perianez, J.; Adrover-Roig, D.; Rodriguez-Sanchez, J.; Rios-Lago, M.; Tirapu, J.; Barcelo, F. Construct validity of the Trail Making Test: Role of task-switching, working memory, inhibition/interference control, and visuomotor abilities. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2009, 15, 438–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budson, A.E.; Solomon, P.R. Memory Loss, Alzheimer’s disease, and dementia e-book: A practical guide for clinicians. Elsevier Health Sci. 2015, 5–38. [Google Scholar]

- Llinàs-Reglà, J.; Vilalta-Franch, J.; López-Pousa, S.; Calvó-Perxas, L.; Torrents Rodas, D.; Garre-Olmo, J. The trail making test: Association with other neuropsychological measures and normative values for adults aged 55 years and older from a Spanish-Speaking Population-based sample. Assessment 2017, 24, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, S.G.; Cardoso, J.R.; Cruz, L.; Lima, R.M.; De Oliveira, R.J.; Iversen, M.D.; Carregaro, R.L. Do virtual reality games improve mobility skills and balance measurements in community-dwelling older adults? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Rehabil. 2017, 31, 1292–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues-Baroni, J.M.; Nascimento, L.R.; Ada, L.; Teixeira-Salmela, L.F. Walking training associated with virtual reality-based training increases walking speed of individuals with chronic stroke: Systematic review with meta-analysis. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2014, 18, 502–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Schaik, P.; Martyr, A.; Blackman, T.; Robinson, J. Involving persons with dementia in the evaluation of outdoor environments. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2008, 11, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, N.E.; McCarthy, C.J.; Adamo, D.E. Handgrip strength as a means of monitoring progression of cognitive decline—A scoping review. Ageing Res. Rev. 2017, 35, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternäng, O.; Reynolds, C.A.; Finkel, D.; Ernsth-Bravell, M.; Pedersen, N.L.; Dahl Aslan, A.K. Grip strength and cognitive abilities: Associations in old age. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2016, 71, 841–848. [Google Scholar]

- Vancampfort, D.; Stubbs, B.; Firth, J.; Smith, L.; Swinnen, N.; Koyanagi, A. Associations between handgrip strength and mild cognitive impairment in middle-aged and older adults in six low-and middle-income countries. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2019, 34, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Best, J.R.; Liu-Ambrose, T.; Boudreau, R.M.; Ayonayon, H.N.; Satterfield, S.; Simonsick, E.M.; Studenski, S.; Yaffe, K.; Newman, A.B.; Rosano, C. An evaluation of the longitudinal, bidirectional associations between gait speed and cognition in older women and men. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2016, 71, 1616–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buracchio, T.; Dodge, H.H.; Howieson, D.; Wasserman, D.; Kaye, J. The trajectory of gait speed preceding mild cognitive impairment. Arch. Neurol. 2010, 67, 980–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, L.J.H.; Caspi, A.; Ambler, A.; Broadbent, J.M.; Cohen, H.J.; D’Arbeloff, T.; Elliott, M.; Hancox, R.J.; Harrington, H.; Hogan, S. Association of neurocognitive and physical function with gait speed in midlife. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e1913123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez, A.; Millán-Calenti, J.C.; Lorenzo-López, L.; Maseda, A. Multisensory stimulation for people with dementia: A review of the literature. Am. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Other Demen. 2013, 28, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, F.D.; Attree, E.A.; Brooks, B.M.; Andrews, T.K. Learning and memory in virtual environments: A role in neurorehabilitation? Questions (and occasional answers) from the University of East London. Presence Teleoperators Virtual Environ. 2001, 10, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, M.; Rey, B.; Rodriguez-Pujadas, A.; Breton-Lopez, J.; Barros-Loscertales, A.; Baños, R.M.; Botella, C.; Alcañiz, M.; Avila, C. A functional magnetic resonance imaging assessment of small animals’ phobia using virtual reality as a stimulus. JMIR Serious Games 2014, 2, e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hikichi, H.; Kondo, K.; Takeda, T.; Kawachi, I. Social interaction and cognitive decline: Results of a 7-year community intervention. Alzheimer’s Dement. Transl. Res. Clin. Interv. 2017, 3, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zunzunegui, M.-V.; Alvarado, B.E.; Del Ser, T.; Otero, A. Social networks, social integration, and social engagement determine cognitive decline in community-dwelling Spanish older adults. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2003, 58, S93–S100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | VR Intervention | Control |

|---|---|---|

| n (male) | 34 (6) | 34 (10) |

| Age (years) | 72.6 ± 5.4 | 72.7 ± 5.6 |

| Education (years) | 9.3 ± 4.0 | 8.4 ± 3.5 |

| Height (m) | 1.58 ± 0.08 | 1.58 ± 0.08 |

| No. of medication intake (n) | 2.3 ± 1.4 | 2.12 ± 1.4 |

| Weight (kg) | 60.7 ± 9.8 | 61.3 ± 9.1 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.3 ± 3.0 | 24.5 ± 2.7 |

| SBP (mg/hg) | 129.6 ± 15.8 | 129.6 ± 17.9 |

| DBP (mg/hg) | 74.8 ± 11.3 | 69.5 ± 11.8 |

| Grip strength (kg) | 22.2 ± 6.3 | 23.4 ± 5.7 |

| Gait speed (s) | 1.15 ± 0.33 | 1.18 ± 0.21 |

| 8-feet Up and Go (s) | 6.27 ± 1.48 | 7.04 ± 2.02 |

| MMSE (score) | 26.0 ± 1.8 | 26.3 ± 3.3 |

| TMT A (s) | 26.3 ± 7.3 | 27.9 ± 9.2 |

| TMT B (s) | 56.6 ± 25.0 | 58.5 ± 28.1 |

| SDST (score) | 33.4 ± 9.0 | 32.4 ± 8.2 |

| Variables | VR Intervention | Control | Group x Time Interaction | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Follow Up | p-Value a | Baseline | Follow Up | p-Value a | p-Value b | Effect Size | |

| Grip strength (kg) | 22.2 ± 6.3 | 24.4 ± 5.3 | 0.03 | 23.4 ± 5.7 | 23.9 ± 5.7 | n.s. | n.s. | - |

| Gait speed (m/s) | 1.15 ± 0.33 | 1.19 ± 0.37 | 0.04 | 1.18 ± 0.21 | 1.12 ± 0.26 * | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.143 |

| 8-feet Up and go (s) | 6.77 ± 1.48 | 6.32 ± 1.92 | 0.02 | 7.04 ± 2.02 | 7.06 ± 1.87 * | n.s. | 0.03 | 0.107 |

| MMSE (score) | 26.0 ± 1.8 | 26.9 ± 2.0 | n.s. | 26.3 ± 3.3 | 26.4 ± 2.7 | n.s. | n.s. | - |

| TMT A (s) | 26.3 ±7.3 | 24.2 ± 5.3 | 0.04 | 27.9 ± 9.2 | 27.8 ± 8.1 | n.s. | n.s. | - |

| TMT B (s) | 56.6 ± 25.0 | 51.3 ± 24.8 | 0.03 | 58.5 ± 28.1 | 63.2 ± 25.1 * | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.208 |

| SDST (score) | 33.4 ± 9.0 | 39.6 ± 9.5 | 0.02 | 32.4 ± 8.2 | 21.8 ± 8.2 | < 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.264 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Thapa, N.; Park, H.J.; Yang, J.-G.; Son, H.; Jang, M.; Lee, J.; Kang, S.W.; Park, K.W.; Park, H. The Effect of a Virtual Reality-Based Intervention Program on Cognition in Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Randomized Control Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1283. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9051283

Thapa N, Park HJ, Yang J-G, Son H, Jang M, Lee J, Kang SW, Park KW, Park H. The Effect of a Virtual Reality-Based Intervention Program on Cognition in Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Randomized Control Trial. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2020; 9(5):1283. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9051283

Chicago/Turabian StyleThapa, Ngeemasara, Hye Jin Park, Ja-Gyeong Yang, Haeun Son, Minwoo Jang, Jihyeon Lee, Seung Wan Kang, Kyung Won Park, and Hyuntae Park. 2020. "The Effect of a Virtual Reality-Based Intervention Program on Cognition in Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Randomized Control Trial" Journal of Clinical Medicine 9, no. 5: 1283. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9051283

APA StyleThapa, N., Park, H. J., Yang, J.-G., Son, H., Jang, M., Lee, J., Kang, S. W., Park, K. W., & Park, H. (2020). The Effect of a Virtual Reality-Based Intervention Program on Cognition in Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Randomized Control Trial. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(5), 1283. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9051283