Prevalence, Bother and Treatment Behavior Related to Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms and Overactive Bladder among Cardiology Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Study Goals

2.4. Statistics

2.5. Ethics

3. Results

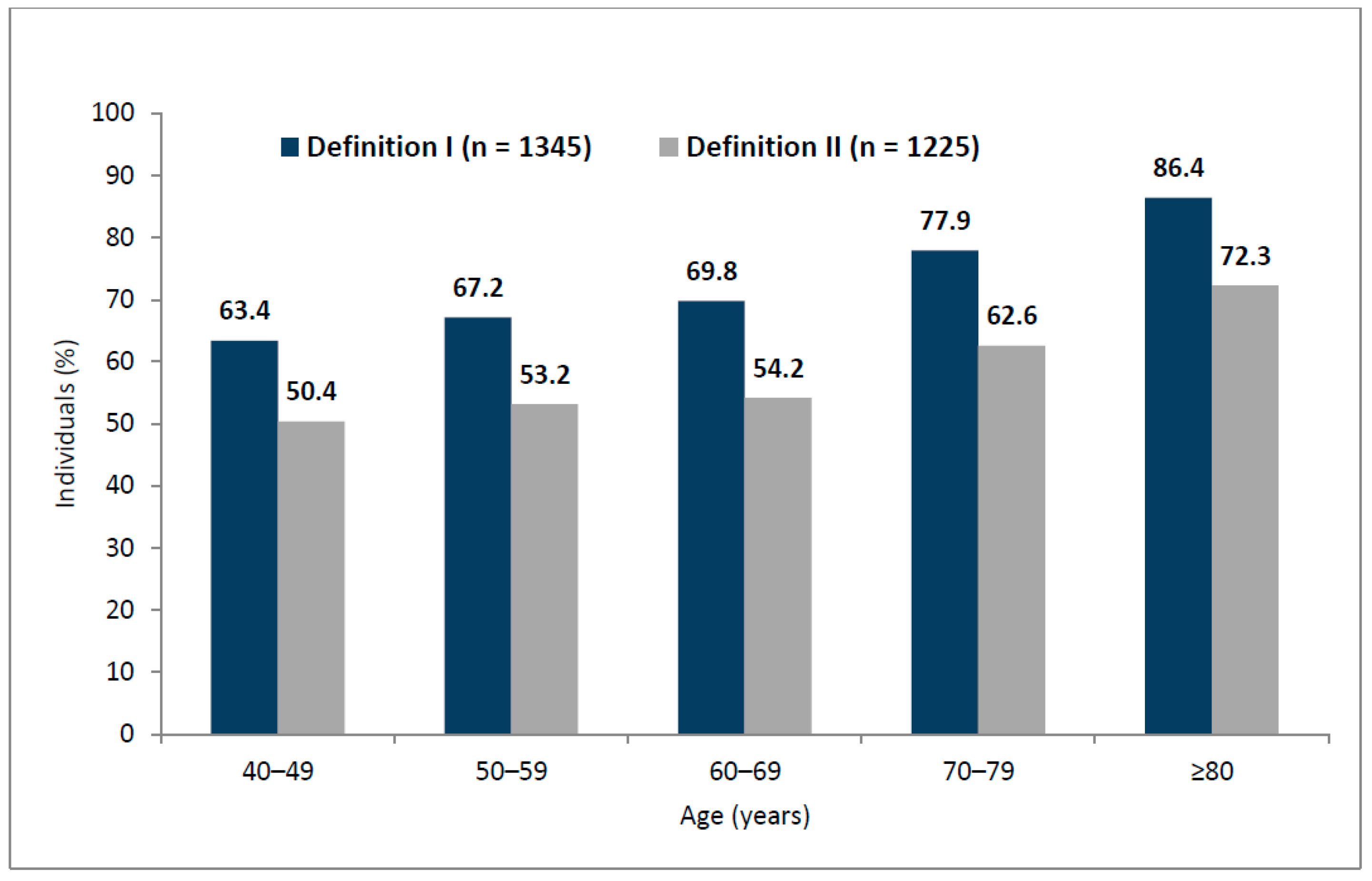

3.1. The Prevalence of LUTS

3.2. The Prevalence of Specific LUTS

3.3. The Prevalence of LUTS Subgroups

3.4. The Bother of Specific LUTS

3.5. The Prevalence of OAB

3.6. The Overall Assessment of LUTS Severity with Effects on Quality of Life

3.7. The Treatment-Related Patterns

3.7.1. Treatment Seeking and Treatment Receiving

3.7.2. Treatment Satisfaction and Treatment Continuation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abrams, P.; Cardozo, L.; Fall, M.; Griffiths, D.; Rosier, P.; Ulmsten, U.; Van Kerrebroeck, P.; Victor, A.; Wein, A. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: Report from the standardisation sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2002, 21, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, K.S.; Sexton, C.C.; Thompson, C.L.; Milsom, I.; Irwin, D.; Kopp, Z.S.; Chapple, C.R.; Kaplan, S.; Tubaro, A.; Aiyer, L.P.; et al. The prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in the USA, the UK and Sweden: Results from the Epidemiology of LUTS (EpiLUTS) study. BJU Int. 2009, 104, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soler, R.; Gomes, C.M.; Averbeck, M.A.; Koyama, M. The prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in Brazil: Results from the epidemiology of LUTS (Brazil LUTS) study. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2017, 37, 1356–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapple, C.; Castro-Díaz, D.; Chuang, Y.-C.; Lee, K.-S.; Liao, L.; Liu, S.-P.; Wang, J.; Yoo, T.K.; Chu, R.; Sumarsono, B. Prevalence of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms in China, Taiwan, and South Korea: Results from a Cross-Sectional, Population-Based Study. Adv. Ther. 2017, 34, 1953–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przydacz, M.; Golabek, T.; Dudek, P.; Lipinski, M.; Chlosta, P. Prevalence and bother of lower urinary tract symptoms and overactive bladder in Poland, an Eastern European Study. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Association of Urology (EAU). Non-Oncology Guidelines [Internet]. Management of Non-neurogenic Male LUTS. 2020. Available online: https://uroweb.org/guideline/treatment-of-non-neurogenic-male-luts/ (accessed on 23 May 2020).

- Semczuk-Kaczmarek, K.; Płatek, A.E.; Szymanski, F.M. Co-treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms and cardiovascular disease—Where do we stand? Central Eur. J. Urol. 2020, 73, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannenbaum, C.; Johnell, K. Managing Therapeutic Competition in Patients with Heart Failure, Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms and Incontinence. Drugs Aging 2013, 31, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.Y.; Moon, J.E.; Sun, H.Y.; Doo, S.W.; Yang, W.J.; Song, Y.S.; Lee, S.-R.; Park, B.-W.; Kim, J.H.; Song, Y.S. Association between lower urinary tract symptoms and cardiovascular risk scores in ostensibly healthy women. BJU Int. 2018, 123, 669–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Lee, S.W.; Kang, H.R.; Kim, D.I.; Sun, H.Y.; Kim, J.H. Relationship between lower urinary tract symptoms and cardiovascular risk scores including Framingham risk score and ACC/AHA risk score. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2018, 37, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupelian, V.; Araujo, A.B.; Wittert, G.; McKinlay, J.B. Association of Moderate to Severe Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms with Incident Type 2 Diabetes and Heart Disease. J. Urol. 2015, 193, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, M.H.; Hardin, S.R.; Behrend, C.; Collins, S.K.-R.; Madigan, C.K.; Carlson, J.R. Urinary Incontinence and Overactive Bladder in Patients With Heart Failure. J. Urol. 2009, 182, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gacci, M.; Corona, G.; Sebastianelli, A.; Serni, S.; De Nunzio, C.; Maggi, M.; Vignozzi, L.; Novara, G.; McVary, K.; Kaplan, S.A.; et al. Male Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms and Cardiovascular Events: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Eur. Urol. 2016, 70, 788–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouwman, I.I.; Voskamp, M.J.H.; Kollen, B.J.; Nijman, R.J.; Van Der Heide, W.K.; Blanker, M.H. Do lower urinary tract symptoms predict cardiovascular diseases in older men? A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J. Urol. 2015, 33, 1911–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Hwang, R.; Chuan, F.; Peters, R.; Kuys, S. Frequency of urinary incontinence in people with chronic heart failure. Hear. Lung 2013, 42, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polska Agencja Rozwoju Przedsiebiorczosci (PARP). Raport Metodologiczny z Badan BKL [Internet]. 2011. Available online: https://www.parp.gov.pl/component/publications (accessed on 23 May 2020).

- Na Strazy Sondazy, Uniwersytet Warszawski [Internet]. 2013. Available online: http://nastrazysondazy.uw.edu.pl/metodologia-badan (accessed on 23 May 2020).

- Glowny Urzad Statystyczny (GUS). Narodowe Spisy Powszechne [Internet]. 2012. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/spisy-powszechne/ (accessed on 23 May 2020).

- Program Kontroli Jakosci Pracy Ankieterow (PKJPA). Organizacja Firm Badania Opinii i Rynku (OBFOR) [Internet]. 2000. Available online: https://www.pkjpa.pl (accessed on 23 May 2020).

- Barry, M.J.; Fowler, F.J.; O’Leary, M.P.; Bruskewitz, R.C.; Holtgrewe, H.L.; Mebust, W.K.; Cockett, A.T. The Measurement Committee of the American Urological Association The American Urological Association Symptom Index for Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. J. Urol. 1992, 148, 1549–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, K.S.; Zyczynski, T.; Margolis, M.K.; Elinoff, V.; Roberts, R.G. Validation of an overactive bladder awareness tool for use in primary care settings. Adv. Ther. 2005, 22, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, K.S.; Sexton, C.C.; Kopp, Z.S.; Luks, S.; Gross, A.; Irwin, D.; Milsom, I. Rationale for the study methods and design of the epidemiology of lower urinary tract symptoms (EpiLUTS) study. BJU Int. 2009, 104, 348–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorente, C. New Concepts in Epidemiology of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms in Men. Eur. Urol. Suppl. 2010, 9, 477–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, D.E.; Milsom, I.; Hunskaar, S.; Reilly, K.; Kopp, Z.; Herschorn, S.; Coyne, K.; Kelleher, C.; Hampel, C.; Artibani, W.; et al. Population-Based Survey of Urinary Incontinence, Overactive Bladder, and Other Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms in Five Countries: Results of the EPIC Study. Eur. Urol. 2006, 50, 1306–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, W.F.; Whishaw, D.M.; Khan, F. Nocturia as a marker of poor health: Causal associations to inform care. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2016, 36, 697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesonen, J.S.; Cartwright, R.; Vernooij, R.W.M.; Aoki, Y.; Agarwal, A.; Mangera, A.; Markland, A.D.; Tsui, J.F.; Santti, H.; Griebling, T.L.; et al. The Impact of Nocturia on Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Urol. 2020, 203, 486–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savarese, G.; Lund, L.H. Global Public Health Burden of Heart Failure. Card. Fail. Rev. 2017, 3, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, R.; Tubaro, A.; Burkhard, F. Nocturia: The Complex Role of the Heart, Kidneys, and Bladder. Eur. Urol. Focus 2020, 6, 534–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilinc, M.F.; Yasar, E.; Aydin, H.I.; Yildiz, Y.; Doluoglu, O.G. Association between coronary artery disease severity and overactive bladder in geriatric patients. World J. Urol. 2017, 36, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De, E.; Hou, P.; Estrera, A.L.; Sdringola, S.; Kramer, L.A.; Graves, D.E.; Westney, O.L. Pelvic Ischemia is Measurable and Symptomatic in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease: A Novel Application of Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging. J. Sex. Med. 2008, 5, 2635–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, G.; Rosen, R.C.; Kloner, R.A.; Kostis, J.B. The second Princeton consensus on sexual dysfunction and cardiac risk: New guidelines for sexual medicine. J. Sex. Med. 2006, 3, 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, A.-F.; Liao, C.-H.; Wang, C.C.; Wang, J.-H.; Tsai, C.-H.; Kuo, H.-C. High Classification of Chronic Heart Failure Increases Risk of Overactive Bladder Syndrome and Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms. Urology 2012, 79, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekundayo, O.J. The association between overactive bladder and diuretic use in the elderly. Curr. Urol. Rep. 2009, 10, 434–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sexton, C.C.; Coyne, K.S.; Kopp, Z.S.; Irwin, D.E.; Milsom, I.; Aiyer, L.P.; Tubaro, A.; Chapple, C.R.; Wein, A.J.; EpiLUTS Team. The overlap of storage, voiding and postmicturition symptoms and implications for treatment seeking in the USA, UK and Sweden: EpiLUTS. BJU Int. 2009, 103 (Suppl. 3), 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwman, I.I.; Blanker, M.H.; Schouten, B.W.V.; Bohnen, A.M.; Nijman, R.J.; Van Der Heide, W.K.; Bosch, J.R. Are lower urinary tract symptoms associated with cardiovascular disease in the Dutch general population? Results from the Krimpen study. World J. Urol. 2015, 33, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Coyne, K.S.; Kaplan, S.A.; Chapple, C.R.; Sexton, C.C.; Kopp, Z.S.; Bush, E.N.; Aiyer, L.P.; EpiLUTS Team. Risk factors and comorbid conditions associated with lower urinary tract symptoms: EpiLUTS. BJU Int. 2009, 103 (Suppl. 3), 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cardiology Participants (n = 1835) | Noncardiology Participants (n = 4170) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptom Prevalence (Definition I) | Symptom Prevalence (Definition II) | Prevalence of Bother (at Least Quite a Bit) a | Symptom Prevalence (Definition I) | Symptom Prevalence (Definition II) | Prevalence of Bother (at Least Quite a Bit) a | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Storage symptoms | ||||||||||||

| Nocturia b | 1520 | 82.8 *** | 849 | 46.3 ** | 401 | 47.2 | 2907 | 69.7 | 1319 | 31.6 | 581 | 44.0 |

| Frequency | 1009 | 55.0 *** | 701 | 38.2 ** | 373 | 53.2 | 1362 | 32.7 | 996 | 23.9 | 504 | 50.6 |

| Urgency | 467 | 25.4 ** | 281 | 15.3 * | 233 | 82.9 | 704 | 16.9 | 392 | 9.4 | 320 | 81.6 |

| Urgency with fear of leaking | 293 | 16.0 * | 217 | 11.8 * | 188 | 86.6 | 446 | 10.7 | 294 | 7.1 | 250 | 85.0 |

| Urge urinary incontinence | 191 | 10.4 * | 104 | 5.7 | 87 | 83.7 | 234 | 5.6 | 138 | 3.3 | 122 | 88.4 |

| Stress urinary incontinence | 190 | 10.4 | 119 | 6.5 * | 108 | 90.8 | 278 | 6.7 | 160 | 3.8 | 149 | 93.1 |

| Mixed urinary incontinence c | 98 | 5.3 | 49 | 2.7 | 45 | 91.8 | 132 | 3.2 | 74 | 1.8 | 68 | 91.9 |

| Leak for no reason | 99 | 5.4 | 57 | 3.1 | 52 | 91.2 | 128 | 3.1 | 66 | 1.6 | 57 | 86.4 |

| Voiding symptoms | ||||||||||||

| Intermittency | 240 | 13.1 | 153 | 8.3 * | 102 | 66.7 | 299 | 7.2 | 173 | 4.1 | 110 | 63.6 |

| Slow stream | 340 | 18.5 * | 189 | 10.3 * | 116 | 61.4 | 439 | 10.5 | 245 | 5.9 | 138 | 56.3 |

| Hesitancy | 183 | 10.0 | 96 | 5.2 | 81 | 84.4 * | 258 | 6.2 | 117 | 2.8 | 76 | 65.0 |

| Straining | 128 | 7.0 * | 67 | 3.7 * | 54 | 80.6 | 140 | 3.4 | 73 | 1.8 | 59 | 80.8 |

| Splitting/spraying | 183 | 10.0 | 93 | 5.1 | 64 | 68.8 | 244 | 5.9 | 119 | 2.9 | 71 | 59.7 |

| Terminal dribble | 336 | 18.3 | 215 | 11.7 | 133 | 61.9 | 560 | 13.4 | 331 | 7.9 | 169 | 51.1 |

| Postmicturition symptoms | ||||||||||||

| Incomplete emptying | 229 | 12.5 | 136 | 7.4 | 103 | 75.7 | 347 | 8.3 | 191 | 4.6 | 136 | 71.2 |

| Postmicturition dribble | 121 | 6.6 | 61 | 3.3 | 53 | 86.9 | 185 | 4.4 | 94 | 2.3 | 74 | 78.7 |

| Men (n = 824) | Women (n = 1011) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptom Prevalence (Definition I) | Symptom Prevalence (Definition II) | Prevalence of Bother (at Least Quite a Bit) a | Symptom Prevalence (Definition I) | Symptom Prevalence (Definition II) | Prevalence of Bother (at Least Quite a Bit) a | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Storage symptoms | ||||||||||||

| Nocturia b | 681 | 82.6 | 383 | 46.5 | 177 | 46.2 | 839 | 83.0 | 466 | 46.1 | 224 | 48.1 |

| Frequency | 404 | 49.0 ** | 341 | 41.4 * | 162 | 47.5 * | 605 | 59.8 | 366 | 36.2 | 211 | 57.7 |

| Urgency | 185 | 22.5 * | 101 | 12.3 * | 80 | 79.2 | 282 | 27.9 | 180 | 17.8 | 153 | 85.0 |

| Urgency with fear of leaking | 109 | 13.2 * | 78 | 9.5 | 73 | 93.6 | 184 | 18.2 | 139 | 13.7 | 115 | 82.7 |

| Urge urinary incontinence | 49 | 5.9 ** | 25 | 3.0 * | 19 | 76.0 | 142 | 14.0 | 79 | 7.8 | 68 | 86.1 |

| Stress urinary incontinence | 22 | 2.7 *** | 14 | 1.7 *** | 12 | 85.7 | 168 | 16.6 | 105 | 10.4 | 96 | 91.4 |

| Mixed urinary incontinence c | 13 | 1.6 *** | 7 | 0.8 *** | 6 | 85.7 | 85 | 8.4 | 42 | 4.2 | 39 | 92.9 |

| Leak for no reason | 33 | 4.0 | 15 | 1.8 | 14 | 93.3 | 66 | 6.5 | 42 | 4.2 | 38 | 90.5 |

| Voiding symptoms | ||||||||||||

| Intermittency | 136 | 16.9 | 89 | 10.8 | 58 | 65.2 | 104 | 10.3 | 64 | 6.3 | 44 | 68.8 |

| Slow stream | 209 | 25.4 * | 119 | 14.4 * | 75 | 63.0 | 131 | 13.0 | 70 | 6.9 | 41 | 58.6 |

| Hesitancy | 122 | 14.8 ** | 65 | 7.9 * | 55 | 84.6 | 61 | 6.0 | 31 | 3.1 | 26 | 83.9 |

| Straining | 90 | 10.9 ** | 51 | 6.2 ** | 43 | 84.3 * | 38 | 3.8 | 16 | 1.6 | 11 | 68.8 |

| Splitting/spraying | 122 | 14.8 ** | 61 | 7.4 ** | 40 | 65.6 | 61 | 6.0 | 32 | 3.2 | 24 | 75.0 |

| Terminal dribble | 210 | 25.5 ** | 144 | 17.5 ** | 88 | 61.1 | 126 | 12.5 | 71 | 7.0 | 45 | 63.4 |

| Postmicturition symptoms | ||||||||||||

| Incomplete emptying | 133 | 16.1 * | 75 | 9.1 | 60 | 80.0 | 96 | 9.5 | 61 | 6.0 | 43 | 70.5 |

| Postmicturition dribble | 67 | 8.1 | 34 | 4.1 | 30 | 88.2 | 54 | 5.3 | 27 | 2.7 | 23 | 85.2 |

| Sex | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Total | p Value | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| OAB-V8 | |||||||

| OAB-V8 score ≥ 8 (cardiology participants) | 376 | 45.6 | 555 | 54.9 | 931 | 50.7 | <0.01 |

| Age category | <0.01 | ||||||

| 40–49 | 19 | 27.9 | 19 | 34.5 | 38 | 30.9 | |

| 50–59 | 65 | 42.5 | 88 | 53.7 | 153 | 48.3 | |

| 60–69 | 136 | 46.7 | 187 | 53.0 | 323 | 50.2 | |

| 70–79 | 96 | 43.0 | 185 | 58.4 | 281 | 52.0 | |

| ≥80 | 60 | 67.4 | 76 | 62.3 | 136 | 64.5 | |

| IPSS | |||||||

| Category (defined by the IPSS score) | 824 | 100 | 1011 | 100 | 1835 | 100 | p = 0.39 |

| None (score 0) | 52 | 6.3 | 66 | 6.5 | 118 | 6.4 | |

| Mild (score 1–7) | 485 | 58.9 | 668 | 66.1 | 1153 | 62.8 | |

| Moderate (score 8–19) | 241 | 29.2 | 254 | 25.1 | 495 | 27.0 | |

| Severe (score 20–35) | 46 | 5.6 | 23 | 2.3 | 69 | 3.8 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Przydacz, M.; Dudek, P.; Chlosta, P. Prevalence, Bother and Treatment Behavior Related to Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms and Overactive Bladder among Cardiology Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 4102. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9124102

Przydacz M, Dudek P, Chlosta P. Prevalence, Bother and Treatment Behavior Related to Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms and Overactive Bladder among Cardiology Patients. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2020; 9(12):4102. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9124102

Chicago/Turabian StylePrzydacz, Mikolaj, Przemyslaw Dudek, and Piotr Chlosta. 2020. "Prevalence, Bother and Treatment Behavior Related to Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms and Overactive Bladder among Cardiology Patients" Journal of Clinical Medicine 9, no. 12: 4102. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9124102

APA StylePrzydacz, M., Dudek, P., & Chlosta, P. (2020). Prevalence, Bother and Treatment Behavior Related to Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms and Overactive Bladder among Cardiology Patients. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(12), 4102. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9124102