Investigating Ethnic Disparity in Living-Donor Kidney Transplantation in the UK: Patient-Identified Reasons for Non-Donation among Family Members

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Questionnaire Content

2.4. Main Exposure and Other Demographics

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Qualitative Analysis

2.7. Ethical Approval and Consent

3. Results

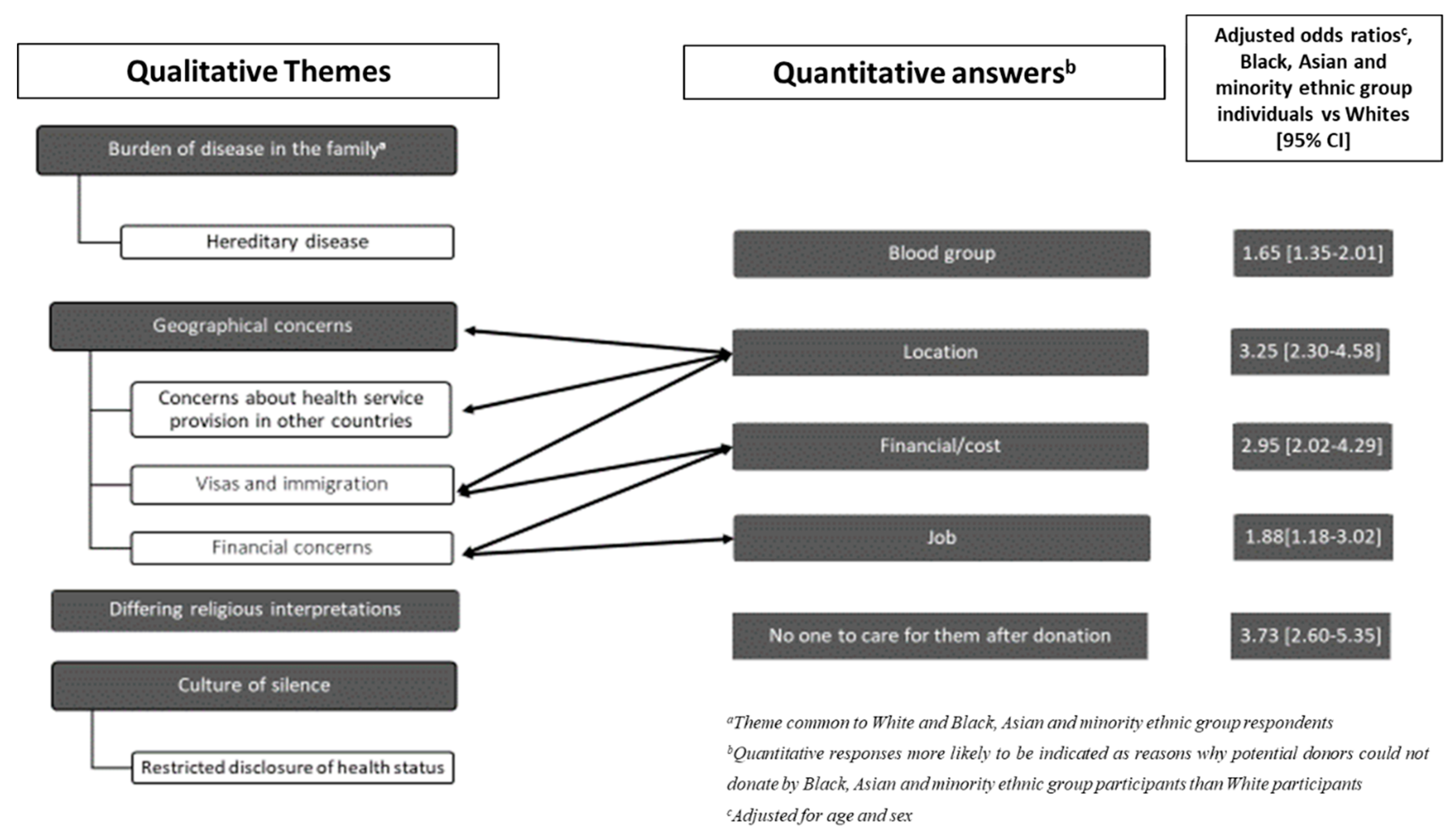

3.1. Quantitative Findings

3.2. Qualitative Findings

3.2.1. Burden of Disease within the Family

“Family history of PKD [polycystic kidney disease]—all siblings, all children and uncles affected.”(Female|50–59 years|Asian|LDKT)

“Too old and unhealthy. Heart problem, Diabetes, high blood pressure, inheritance.”(Male|60–69 years|Asian|Sikh|DDKT)

“There were genetic issues that were contra-indications such as a cause of cancer which was discovered during screening…”(Male|20–29 years|Asian|Muslim|DDKT)

3.2.2. Differing Religious Interpretations

“Their religion would not allow them to donate a kidney.”(Female|40–49 years|Black|Christian| LDKT)

and a discordance between the participants’ and their relatives’ interpretations of their faith:“Superstition/religion (distorted beliefs). Myth.”(Female|60–69 years|Black|LDKT)

“Their religion/faith forbids them to donate… thought they were Christians like me.”(Female|60–69 years|Black|LDKT)

3.2.3. Geographical Concerns

“While some are abroad they were willing to travel.”(Male|60–69 years|Black|Christian|LDKT)

prohibitive financial concerns:“Immigration rules can be problematic too.”(Male|40–49 years|Black|Muslim|LDKT)

and concerns about the quality of post-donation healthcare in their potential donor’s country of residence:“My blood relatives live outside the UK. The financial cost has been a major issue.”(Male|50–59 years|Other ethnic group|DDKT)

“I come from Papua New Guinea and health services are poor. People are afraid of death during and after donating of their kidneys. After operations the care given is not very good and people end up dying. We lost two relatives from sepsis.”(Female|50–59 years| Other ethnic group|Christian|LDKT)

3.2.4. A culture of Silence

“Are unaware of my current condition.”(Male|20–29 years|Asian|Hindu|LDKT)

“…my reluctance to show how ill I was, to soldier on, accept my fate and manage accordingly.”(Male|50–59 years|Asian|Sikh|LDKT)

“The majority of my extended family do not ‘officially’ know that I am unwell/having dialysis or had a transplant as my parents did not want them to know.”(Male|30–39 years|Other ethnic group|Other religion|DDKT)

3.2.5. Responses from White Participants

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cecka, J.M. Living donor transplants. Clin. Transpl. Jan. 1995, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Terasaki, P.I.; Cecka, J.M.; Gjertson, D.W.; Takemoto, S. High Survival Rates of Kidney Transplants from Spousal and Living Unrelated Donors. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995, 333, 333–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laupacis, A.; Keown, P.; Pus, N.; Krueger, H.; Ferguson, B.; Wong, C.; Muirhead, N. A study of the quality of life and cost-utility of renal transplantation. Kidney Int. 1996, 50, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cecka, J.M. The OPTN/UNOS Renal Transplant Registry. Clin Transpl. 2005, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Roodnat, J.I.; Van Riemsdijk, I.C.; Mulder, P.G.H.; Doxiadis, I.; Claas, F.H.J.; Ijzermans, J.N.M.; Weimar, W. The superior results of living-donor renal transplantation are not completely caused by selection or short cold ischemia time: A single-center, multivariate analysis. Transplantation 2003, 75, 2014–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annual Activity Report—ODT Clinical—NHS Blood and Transplant. Published 2019. Available online: https://www.odt.nhs.uk/statistics-and-reports/annual-activity-report/ (accessed on 19 February 2020).

- Barnieh, L.; Manns, B.J.; Klarenbach, S.; McLaughlin, K.; Yilmaz, S.; Hemmelgarn, B.R. A description of the costs of living and standard criteria deceased donor kidney transplantation. Am. J. Transpl. 2011, 11, 478–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.R.; Woodward, R.S.; Cohen, D.S.; Singer, G.G.; Brennan, D.C.; Lowell, J.A.; Schnitzler, M.A. Cadaveric versus living donor kidney transplantation: A medicare payment analysis. Transplantation 2000, 69, 311–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggiore, U.; Budde, K.; Heemann, U.; Hilbrands, L.; Oberbauer, R.; Oniscu, G.C.; Abramowicz, D. Long-term risks of kidney living donation: Review and position paper by the ERA-EDTA DESCARTES working group. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 2017, 32, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzaale, A.D.; Massie, A.B.; Wang, M.C.; Montgomery, R.A.; McBride, M.A.; Wainright, J.L.; Segev, D.L. Risk of end-stage renal disease following live kidney donation. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2014, 311, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massie, A.B.; Muzaale, A.D.; Luo, X.; Chow, E.K.; Locke, J.E.; Nguyen, A.Q.; Segev, D.L. Quantifying postdonation risk of ESRD in living kidney donors. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2017, 28, 2749–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segev, D.L.; Muzaale, A.D.; Caffo, B.S.; Mehta, S.H.; Singer, A.L.; Taranto, S.E.; Montgomery, R.A. Perioperative mortality and long-term survival following live kidney donation. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2010, 303, 959–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lumsdaine, J.A.; Wray, A.; Power, M.J.; Jamieson, N.V.; Akyol, M.; Andrew Bradley, J.; Wigmore, S.J. Higher quality of life in living donor kidney transplantation: Prospective cohort study. Transpl. Int. 2005, 18, 975–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, E.M.; Anderson, J.K.; Jacobs, C.; Suh, G.; Humar, A.; Suhr, B.D.; Matas, A.J. Long-term follow-up of living kidney donors: Quality of life after donation. Transplantation 1999, 67, 717–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IRODaT—International Registry on Organ Donation and Transplantation. Available online: http://www.irodat.org/?p=database (accessed on 27 February 2020).

- Udayaraj, U.; Ben-Shlomo, Y.; Roderick, P.; Casula, A.; Dudley, C.; Collett, D.; Caskey, F. Social deprivation, ethnicity, and uptake of living kidney donor transplantation in the United Kingdom. Transplantation 2012, 93, 610–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.A.; Robb, M.L.; Watson, C.J.E.; Forsythe, J.L.; Tomson, C.R.; Cairns, J.; Bradley, C. Barriers to living donor kidney transplantation in the United Kingdom: A national observational study. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 2017, 32, 890–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lentine, K.L.; Kasiske, B.L.; Levey, A.S.; Adams, P.L.; Alberú, J.; Bakr, M.A.; Segev, D.L. KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline on the Evaluation and Care of Living Kidney Donors. Transplantation 2017, 101, S1–S109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigue, J.R.; Kazley, A.S.; Mandelbrot, D.A.; Hays, R.; Rudow, D.L.P.; Baliga, P. Living donor kidney transplantation: Overcoming disparities in live kidney donation in the US—Recommendations from a consensus conference. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2015, 10, 1687–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M.; Kenten, C.; Deedat, S.; on behalf of the Donation, Transplantation and Ethnicity (DonaTE) Programme Team. Attitudes to deceased organ donation and registration as a donor among minority ethnic groups in North America and the UK: A synthesis of quantitative and qualitative research. Ethn. Health 2013, 18, 367–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnaes, A.H. Lost in translation: Cultural obstructions impede living kidney donation among minority ethnic patients. Cambridge Q. Healthc. Ethics 2012, 21, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, P.K.; Tomson, C.R.V.; MacNeill, S.; Marsden, A.; Cook, D.; Cooke, R.; Ben-Shlomo, Y. A multicenter cohort study of potential living kidney donors provides predictors of living kidney donation and non-donation. Kidney Int. 2017, 92, 1249–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, R.S. The case for combining qualitative and quantitative approaches in health services research. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 1999, 4, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, P.K.; Tomson, C.R.V.; Ben-Shlomo, Y. What factors explain the association between socioeconomic deprivation and reduced likelihood of live-donor kidney transplantation? A questionnaire-based pilot case-control study. BMJ Open 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)-A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, P.K.; Ben-Shlomo, Y.; Tomson, C.R.V.; Owen-Smith, A. Socioeconomic deprivation and barriers to live-donor kidney transplantation: A qualitative study of deceased-donor kidney transplant recipients. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2011 Census Analysis: Ethnicity and Religion of the non-UK Born Population in England and Wales—Office for National Statistics. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/culturalidentity/ethnicity/articles/2011censusanalysisethnicityandreligionofthenonukbornpopulationinenglandandwales/2015-06-18 (accessed on 19 February 2020).

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15; StataCorp LLC: College Station, TX, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldaña, J. Qualitative Data Analysis A Methods Sourcebook, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 2007, 335, 806–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHS England. Commissioning Policy: Reimbursement of Expenses for Living Donors. Reference: NHS England A06/P/a June 2017. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/commissioning-policy-reimbursement-of-expenses-for-living-donors/ (accessed on 28 September 2020).

- Bailey, P.K.; Caskey, F.J.; MacNeill, S.; Tomson, C.; Dor, F.J.M.F.; Ben-Shlomo, Y. Beliefs of UK Transplant Recipients about Living Kidney Donation and Transplantation: Findings from a Multicentre Questionnaire-Based Case–Control Study. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 9, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubair, M.; Jurisconsult, B. Organ Donation and Transplantation in Islam An Opinion. Available online: https://nhsbtdbe.blob.core.windows.net/umbraco-assets-corp/16300/organ-donation-fatwa.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Davis, L.A.; Grogan, T.M.; Cox, J.; Weng, F.L. Inter- and Intrapersonal Barriers to Living Donor Kidney Transplant among Black Recipients and Donors. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2017, 4, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerrato, A.; Avitable, M.; Hayman, L.L. The relationship between the sick role and functional ability: One center’s experience. Prog. Transpl. 2008, 18, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, P.; Caskey, F.; MacNeill, S.; Tomson, C.; Dor, F.J.; Ben-Shlomo, Y. Mediators of socioeconomic inequity in living-donor kidney transplantation: Results from a UK multicenter case-control study. Transpl. Direct. 2020, 6, e540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browne, T. The relationship between social networks and pathways to kidney transplant parity: Evidence from black Americans in Chicago. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 73, 663–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, C.R.; Hicks, L.S.; Keogh, J.H.; Epstein, A.M.; Ayanian, J.Z. Promoting access to renal transplantation: The role of social support networks in completing pre-transplant evaluations. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2008, 23, 1187–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lpez-Navas, A.; Ros, A.; Riquelme, A.; Martínez-Alarcón, L.; Pons, J.A.; Miras, M.; Parrilla, P. Psychological care: Social and family support for patients awaiting a liver transplant. Transplant. Proc. 2011, 43, 701–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, S.Y.; Luchtenburg, A.E.; Timman, R.; Zuidema, W.C.; Boonstra, C.; Weimar, W.; Massey, E.K. Home-based family intervention increases knowledge, communication and living donation rates: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Transpl. 2014, 14, 1862–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garonzik-Wang, J.M.; Berger, J.C.; Ros, R.L.; Kucirka, L.M.; Deshpande, N.A.; Boyarsky, B.J.; Segev, D.L. Live donor champion: Finding live kidney donors by separating the advocate from the patient. Transplantation 2012, 93, 1147–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterman, A.D.; Wood, E.H.; Ranasinghe, O.N.; Lipsey, A.F.; Anderson, C.; Balliet, W.; Salas, M.A.P. A Digital Library for Increasing Awareness About Living Donor Kidney Transplants: Formative Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2020, 4, e17441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunsford, S.L.; Simpson, K.S.; Chavin, K.D.; Menching, K.J.; Miles, L.G.; Shilling, L.M.; Baliga, P.K. Racial Disparities in Living Kidney Donation: Is There a Lack of Willing Donors or an Excess of Medically Unsuitable Candidates? Transplantation 2006, 82, 876–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robb, K.A.; Gatting, L.; Wardle, J. What impact do questionnaire length and monetary incentives have on mailed health psychology survey response? Br. J. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 671–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, S.; Henderson, J.; Alderdice, F.; Quigley, M.A. Methods to increase response rates to a population-based maternity survey: A comparison of two pilot studies. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2019, 19, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaats, D.; Lennerling, A.; Pronk, M.C.; van der Pant, K.A.; Dooper, I.M.; Wierdsma, J.M.; Zuidema, W.C. Donor and Recipient Perspectives on Anonymity in Kidney Donation From Live Donors: A Multicenter Survey Study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2018, 71, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salway, S.; Holman, D.; Lee, C.; McGowan, V.; Ben-Shlomo, Y.; Saxena, S.; Nazroo, J. Transforming the health system for the UK’s multiethnic population. BMJ 2020, 368, m268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiessen, C.; Kulkarni, S.; Reese, P.P.; Gordon, E.J. A Call for Research on Individuals Who Opt Out of Living Kidney Donation. Transplantation 2016, 100, 2527–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Participants (n = 1240) n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 514 (41.5) |

| Male | 705 (56.9) | |

| Missing | 21 (1.7) | |

| Type of transplant | Living-donor kidney transplant | 672 (54.2) |

| Deceased-donor kidney transplant | 565 (45.6) | |

| Missing | 3 (0.2) | |

| Age group (years) a | 20–29 | 74 (6.0) |

| 30–39 | 137 (11.1) | |

| 40–49 | 209 (16.9) | |

| 50–59 | 331 (26.7) | |

| 60–69 | 299 (24.1) | |

| 70–79 | 150 (12.1) | |

| 80–89 | 6 (0.5) | |

| Missing | 34 (2.7) | |

| Self-reported Ethnicity b | White | 1027 (82.8) |

| Asian/Asian-British | 79 (6.4) | |

| Black/African/Caribbean/Black British | 58 (4.7) | |

| Mixed/Multiple ethnic groups | 10 (0.8) | |

| Other Ethnic groups | 24 (1.9) | |

| Missing | 42 (3.4) | |

| Religion | Christian | 717 (57.8) |

| Hindu | 27 (2.2) | |

| Sikh | 13 (1.1) | |

| Muslim | 21 (1.7) | |

| Jewish | 6 (0.5) | |

| No religion | 335 (27.0) | |

| Other | 38 (3.1) | |

| Missing | 74 (6.0) | |

| Reported Reason Potential Donor not Suitable for Donation | White n = 1027, n (%) | Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic Group n = 171, n (%) | White vs. Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic Group Chi2 p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age—too old or too young to donate | 562 (54.8) | 94 (55.0) | 0.96 |

| Health—not healthy enough to donate | 648 (63.2) | 109 (63.7) | 0.88 |

| Weight—too over or underweight to donate | 152 (14.8) | 30 (17.5) | 0.36 |

| Location—they live too far away to be able to donate | 188 (18.3) | 72 (42.1) | <0.001 |

| Financial/cost—the financial impact of donation would be too much | 98 (9.6) | 40 (23.4) | <0.001 |

| Job—not able to take the time off work to donate | 106 (10.3) | 29 (17.0) | <0.001 |

| Blood group—not the right blood group to donate | 199 (19.4) | 51 (29.8) | 0.002 |

| No-one to care for them after donation | 63 (6.1) | 32 (18.7) | <0.001 |

| Reported Reason Potential Donor Not Suitable for Donation | Black, Asian and Minority Ethnicities vs. White Unadjusted Odds Ratio (OR) [95% Confidence Interval (CI)] | Black, Asian and Minority Ethnicities vs. White Adjusted for Sex and Age OR [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|

| Age—too old or too young | 1.00 [0.75–1.34] | 0.98 [0.73–1.32] |

| Health—not healthy enough | 1.02 [0.78–1.34] | 0.96 [0.71–1.31] |

| Weight—too over or underweight | 1.22 [0.84–1.77] | 1.13 [0.78–1.65] |

| Location—live too far away | 3.23 [2.23–4.68] | 3.25 [2.30–4.58] |

| Financial/cost—financial impact of donation would be too much | 2.89 [2.07–4.03] | 2.95 [2.02–4.29] |

| Job—not able to take time off work | 1.77 [1.15–2.71] | 1.88 [1.18–3.02] |

| Blood group—not the right blood group | 1.76 [1.43–2.17] | 1.65 [1.35–2.01] |

| No-one to care for them after donation | 3.51 [2.47–4.99] | 3.73 [2.60–5.35] |

| Theme | Representative Quote |

|---|---|

| Burden of disease within family | “Very healthy but slight amount of protein in urine so not able to donate.” (Male, 50–59 years, Asian, Hindu, Living-donor kidney transplant (LDKT) “They all have slight renal problem” (Female, 50–59 years, Black, Deceased-donor kidney transplant (DDKT) “Hereditary illness in the family” (Male, 50–59 years, Asian, DDKT) “Mother and 2 sibling have same condition as mine (1 sister & 1 brother).” (Male, 30–38 years, Black, Christian, DDKT) |

| Differing religious interpretations | “Their religion/faith forbids them to donate 1. thought they were Christians like me. 2. our culture forbids them to donate… 3. some forbid blood transfusion and the unbelievable reasons for that.” (Female, 60–69 years, Black, LDKT) “Superstition/religion (distorted beliefs). Myth.” (Female, 50–59 years, Black, Christian, DDKT) “Their religion would not allow them to donate a kidney.” (Female, 40–49 years, Black, Christian, LDKT) “Religious/cultural…” (Male, 50–59 years, Asian, Hindu, LDKT) |

| Geographical concerns | “All of my family apart from my spouse live in Ethiopia and other countries and would not have access to healthcare or the means to come to the UK” (Male, 40–49 years, Black, Muslim, LDKT) “All my people are in Nigeria, some of them, lack of transport to help them home is the problem some of them have.” (Male, 70–79 years, Black, Christian, DDKT) “I had a word with my mum, wife and my son but they couldn’t come to the UK due to financial and other reasons.” (Male, 40–49 years, Black, Christian, DDKT) |

| A culture of silence | “I did not ask for a donation so do not have a reason.” (Female, 60–69 years, Asian, Sikh, DDKT) “I would not ask my cousins” (Female, 30–39 years, Asian, Muslim, LDKT) “Other 3 cousins from my mother’s half sister do not have PKD but they would not offer, they didn’t before, I would certainly not ask.” (Female, 60–69 years, Other ethnic group, No religion, LDKT) “Are unaware of my current condition.” (Male, 20–29 years, Asian, Hindu, LDKT) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wong, K.; Owen-Smith, A.; Caskey, F.; MacNeill, S.; Tomson, C.R.V.; Dor, F.J.M.F.; Ben-Shlomo, Y.; Bouacida, S.; Idowu, D.; Bailey, P. Investigating Ethnic Disparity in Living-Donor Kidney Transplantation in the UK: Patient-Identified Reasons for Non-Donation among Family Members. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3751. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9113751

Wong K, Owen-Smith A, Caskey F, MacNeill S, Tomson CRV, Dor FJMF, Ben-Shlomo Y, Bouacida S, Idowu D, Bailey P. Investigating Ethnic Disparity in Living-Donor Kidney Transplantation in the UK: Patient-Identified Reasons for Non-Donation among Family Members. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2020; 9(11):3751. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9113751

Chicago/Turabian StyleWong, Katie, Amanda Owen-Smith, Fergus Caskey, Stephanie MacNeill, Charles R.V. Tomson, Frank J.M.F. Dor, Yoav Ben-Shlomo, Soumeya Bouacida, Dela Idowu, and Pippa Bailey. 2020. "Investigating Ethnic Disparity in Living-Donor Kidney Transplantation in the UK: Patient-Identified Reasons for Non-Donation among Family Members" Journal of Clinical Medicine 9, no. 11: 3751. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9113751

APA StyleWong, K., Owen-Smith, A., Caskey, F., MacNeill, S., Tomson, C. R. V., Dor, F. J. M. F., Ben-Shlomo, Y., Bouacida, S., Idowu, D., & Bailey, P. (2020). Investigating Ethnic Disparity in Living-Donor Kidney Transplantation in the UK: Patient-Identified Reasons for Non-Donation among Family Members. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(11), 3751. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9113751