Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic made imperative the search for means to end it, which requires a knowledge of the mechanisms underpinning the multiplication and spread of its cause, the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Many viruses use members of the hosts’ chaperoning system to infect the target cells, replicate, and spread, and here we present illustrative examples. Unfortunately, the role of chaperones in the SARS-CoV-2 cycle is still poorly understood. In this review, we examine the interactions of various coronaviruses during their infectious cycle with chaperones in search of information useful for future research on SARS-CoV-2. We also call attention to the possible role of molecular mimicry in the development of autoimmunity and its widespread pathogenic impact in COVID-19 patients. Viral proteins share highly antigenic epitopes with human chaperones, eliciting anti-viral antibodies that crossreact with the chaperones. Both, the critical functions of chaperones in the infectious cycle of viruses and the possible role of these molecules in COVID-19 autoimmune phenomena, make clear that molecular chaperones are promising candidates for the development of antiviral strategies. These could consist of inhibiting-blocking those chaperones that are necessary for the infectious viral cycle, or those that act as autoantigens in the autoimmune reactions causing generalized destructive effects on human tissues.

Keywords:

virus; molecular chaperones; Coronaviridae; SARS-CoV-2; COVID-19; chaperonopathies; chaperonotherapy 1. Introduction

Viruses need molecules from the host cell for their survival and dissemination and molecular chaperones are among them. A timely question is about the role of molecular chaperones in the cycle of the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, the cause of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

Coronaviruses (CoVs) belong to the order Nidovirales and to the family Coronaviridae [1]. The subfamily encompasses four genera Alphacoronavirus, Betaconavirus, Gammacoronavirus, and Deltacoronavirus (α, β, γ, and δ-CoVs, respectively), and is of interest in the medical and veterinary fields. α-CoVs and β-CoVs infect mostly mammals, γ-CoVs and δ-CoVs infect birds [2,3].

CoVs are enveloped viruses with a diameter of about 100 nm with a plus-strand RNA, up to 32 kb [4]. The viral genome produces messenger RNAs (mRNAs) corresponding to the canonical structural proteins: E (envelope), M (membrane), N (nucleocapsid), and S (spike) proteins, the latter forming the distinctive corona of the viral particle [5,6].

The S protein is essential for CoVs infectivity because it contains the receptor-binding domain (RBD) and the domains involved in its fusion with the plasma-cell membrane of the host cell [7].

CoVs primarily infect the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts of a wide range of animal species, including mammals and birds. Genetic and phylogenetic analyses have shown that CoVs have crossed species barriers frequently, even reaching humans [8,9]. CoVs infections of humans (HCoVs) seem to have originated from bat CoVs (BtCoVs). From the early 2000s to today, the world has witnessed three of these zoonotic events caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The latter is the most recent and has forced extraordinary measures globally, including quarantine of individuals and interruption of all kinds of human activities. SARS-CoV-2 can cause severe respiratory-tract disease and damage in various organs, such as kidneys, brain, heart, and liver with a high mortality rate [10,11,12,13,14,15]. The clinical importance of CoVs and the possibility of causing epidemics had not been duly recognized until the appearance of SARS-CoV and the MERS-CoV [16,17]. In December 2019, the new SARS-CoV-2 associated with a severe acute respiratory syndrome, quickly spread in the city of Wuhan (China), causing COVID-19 (coronavirus disease-19), affecting over 41 million people and killing over one million worldwide, at the time of this writing (latest WHO data updated October 24, 2020). This made COVID-19 a major concern for global health [18].

These events have a great negative impact on the world’s population and have forced the scientific community to quickly try to develop means for stopping infections and curing the sick [19]. Strategies for therapies may focus on the identification of the viral structures, such as the spikes with which the virus recognizes and binds to its target cells, or on the identification of the receptor in the target cell, which is recognized by the virus. Both, SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 penetrate human cells using the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), while dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4) represents the access receptor for MERS-CoV. Both types of receptors, which are recognized and bound by the viral spikes, are present in many tissues, such as heart, kidneys, and type 2 pulmonary alveoli [20,21,22]. It is, therefore, clear that the S protein represents a promising therapeutic target [14].

Viruses, like other infectious agents, when invading a host call into action the chaperoning (chaperone) system, which on the one side defends the infected organism and on the other it may help the attacker. The latter situation, a chaperonopathy by mistake [23], occurs when the infectious agent, such as a virus, commandeers one or more components of the chaperoning system of the infected organism and re-directs their activity to favor infection instead of counteracting its effects.

The chaperoning system is composed of molecular chaperones, co-chaperones, chaperone co-factors and chaperone interactors and receptors [23,24] that may form functional networks [25]. Molecular chaperones are proteins that have been sorted by molecular weight into various groups from the smallest (<35 kDa) to the very large (over 200 kDa) [23,26]. In some of these groups are classified molecules called Hsp (Heat Shock Protein) that belong to families of phylogenetically related proteins, such as the small Hsp with the crystallin domain, Hsp40(DnaJ), Hsp70(DnaK), and Hsp90. Although, chaperones in general are cytoprotective, when abnormal they can become pathogenic and cause disease, a chaperonopathy [27]. Chaperonopathies can be genetic or acquired with the former being the result of a genetic variant, e.g., a mutation, in the gene encoding the affected chaperone, whereas in acquired chaperonopathies the gene encoding the sick chaperone is normal but its protein product is not because it has suffered a change after transcription, for example, an aberrant post-translational modification (i.e., deacetylation, phosphorylation, or nitration). These acquired modifications may change drastically the properties of the chaperone and may be one of the mechanisms used by viruses, or cancers for instance, to make the chaperone work for their own benefit. In this situation, whereby a chaperone works for the “enemy”, so to speak, we have a chaperonopathy by mistake or collaborationism [28]. For example, it has been demonstrated that IAV (influenza A virus) induces Hsp90 acetylation leading to the nuclear import of its polymerases favouring viral replication. Therefore, Hsp90 inhibitors that block Hsp90 deacetylation could be used to treat IVA infection as well as others, such as SARS-CoV-2 [29,30].

The purpose of this review is to survey the literature and compile examples of interactions of viruses with chaperones, focusing on information that might be relevant to COVID-19, the disease caused by SARS-CoV-2, and thereby reveal points of attack for agents aimed at preventing infection, and/or blocking the chaperone-depending pathogenic mechanisms.

2. Molecular Chaperones and Viral Infection

Viruses are obligate intracellular parasites able to invade virtually all cells. Despite their apparent simplicity, viruses can control the host cell transcriptional/translational and metabolic machineries and the chaperoning system and use them to sustain their life cycle and carry on a productive infection.

Viruses that do not have chaperones of their own must use those of the infected host for their own sake [31]. However, many aspects of the virus-induced over expression of host’s chaperones are still incompletely understood and some are baffling, particularly because an increase of chaperoning activity may also be cytoprotective. On the one side, overexpression of some chaperones could have an antiviral effect by, for instance, stimulating an immune response against the virus, or promoting infected cells death [32,33,34], Table 1. On the other side, over expression of chaperones could favor the life cycle of the virus, including virus entry [35,36,37,38,39], and disassembly [40], nuclear import, assembly and activation of viral polymerases, as well as nuclear translocation of viral genome, and activation of replication and transcription events [41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52], and structural protein synthesis, and viral particle assembly and release [53,54,55,56]. The last steps specifically involve not only cytosolic chaperones, but also the chaperones typically expressed in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), such as the glucose-regulated proteins (GRPs), calnexin and calreticulin [57,58], Table 1. Regarding the interplay between viruses and host cell ER, usually viral infection cause ER stress with accumulation and aggregation of misfolded proteins and activation of the unfolded protein response (UPR) [59]. UPR signaling, involving the activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), the inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1), and the protein kinase R (PKR)-like ER kinase (PERK), induces the up-regulation of ER chaperones and other molecules required to counteract the accumulation of misfolded/unfolded proteins, including their degradation [60,61]. The UPR can be, either beneficial to viral infection because ER chaperones enhance the folding of viral proteins, or harmful because elevated expression of factors involved in protein degradation may degrade viral proteins. Therefore, to survive ER stress and UPR and to use ER chaperones for their own benefit, viruses have developed specific mechanisms [58,62,63,64]. In addition, many viruses can use the host’s chaperone system to regulate apoptosis to delay host-cell early death and promote their growth and subsequent release [65,66,67,68,69], Table 1.

Table 1.

Role of molecular chaperones in virus infections.

Both the antiviral and the pro-infection activities of molecular chaperones present opportunities for developing anti-viral therapies, for instance by inhibiting molecular chaperones having a pro-infection activity, or by exploiting their immune activity [70,71,72,73,74].

4. Conclusions and Perspectives

Coronaviruses, as well as other viruses, use the host’s chaperone system for the folding of their proteins and for viral assembly, translocation to the nucleus, and other vital steps Figure 2, Table 1. The host’s chaperones and their teams and networks are necessary for virus infection, survival, and spreading. It is, therefore, pertinent to classify some viral diseases within the chaperonopathies by mistake [28]. These are diseases in which normal chaperones (normal, at least to the extent that it can be determined with current technology, but we cannot exclude that they have undergone post-translational modifications that changed their properties) are etio-pathogenic factors, favoring the disease rather than protecting the organism against it. This opens the possibility of including chaperonotherapy in the therapeutic armamentarium, specifically negative chaperonotherapy, which consists of eliminating or blocking the pathogenic chaperone [81,92,116]. It is, therefore, of great interest to elucidate the role of chaperones in the SARS-CoV-2 infectious cycle, and to pinpoint chaperone-dependent steps that can be targeted by chaperone inhibitors, and the chaperones that should be eliminated or inhibited by negative chaperonotherapy. For example, chemical chaperones, such as tauroursodeoxycholic acid (TUDCA) and 4-phenyl butyric acid (PBA), have been proposed for use as therapeutic agents against the ER stress, induced by CoVs infection [92,117,118]. However, with the advances in the knowledge of the chaperoning system it becomes necessary to look at the field of chaperones and viruses with novel eyeglasses, so to speak. Chaperones do not act alone when exercising their canonical functions, namely those pertinent to protein homeostasis and quality control that are needed by virus throughout their life cycles. Therefore, studies aimed at dissecting the role of chaperones in virus biology must consider the fact that chaperones form teams (e.g., homo- or hetero-oligomers) and networks, including chaperones of various classes, co-chaperones, and chaperone co-factors to exercise their canonical functions. In addition, chaperones also have non-canonical functions, largely unrelated to protein homeostasis and quality control, but whether these non-canonical functions play any role in virus biology is still unclear. This is, precisely, another topic of great interest for exploration in the quest for a full understanding of how pathogenic viruses infect cells, and kill patients, and of how they might be defeated using methods and agents centered on components of the chaperoning system.

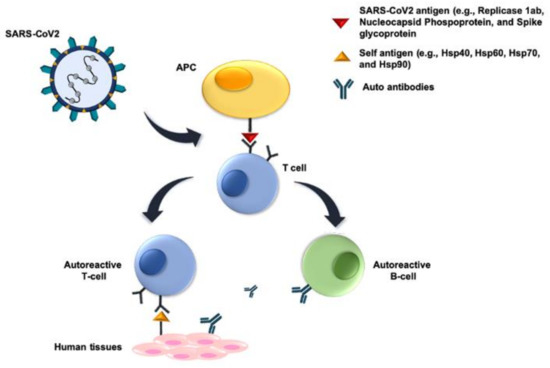

Also of note, is the recently posited working hypothesis incorporating molecular mimicry of human chaperones by viral proteins in the equation leading to autoimmunity and multiorgan failure in COVID-19. External agents, such as viral infections, may induce autoimmunity by the mechanism of molecular mimicry, leading to an activation of autoreactive T or B cells due to the similarities between foreign and self-peptides. For instance, some viruses, such as Epstein-Barr virus and herpesviruses, have been implicated in the development of multiple sclerosis, autoimmune encephalitis, and other autoimmune diseases [119,120]. It has been shown that 3,781 human proteins (17 of them are molecular chaperones) share peptides of at least six amino acids with SARS-CoV-2 proteins [114], opening new avenues for treatments using immunomodulatory strategies targeted to the chaperones bearing epitopes crossreactive with viral antigens.

Author Contributions

L.P. and A.M.V. wrote the manuscript drafts after critically examining the literature, and prepared figures; A.J.L.M., E.C.d.M., C.C.B., and F.C. critically examined the data reported, and contributed to the writing; A.M.G. conceived the study, critically examined the data reported, and contributed to the writing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

A.J.L.M. and E.C.d.M. were partially supported by IMET and IEMEST. This is IMET contribution number IMET 20-021.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Tyrrell, D.A.; Almeida, J.D.; Cunningham, C.H.; Dowdle, W.R.; Hofstad, M.S.; McIntosh, K.; Tajima, M.; Zakstelskaya, L.Y.; Easterday, B.C.; Kapikian, A.; et al. Coronaviridae. Intervirology 1975, 5, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulswit, R.J.; De Haan, C.A.; Bosch, B.J. Coronavirus spike protein and tropism changes. Adv. Virus Res. 2016, 96, 29–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J. SARS-CoV-2: An emerging coronavirus that causes a global threat. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 16, 1678–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, H.A.; Macnaughton, M.R. Comparison of the morphology of three coronaviruses. Arch. Virol. 1979, 59, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masters, P.S. The molecular biology of coronaviruses. Adv. Virus. Res. 2006, 66, 193–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawicki, S.G.; Sawicki, D.L.; Siddell, S.G. A contemporary view of coronavirus transcription. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heald-Sargent, T.; Gallagher, T. Ready, set, fuse! The coronavirus spike protein and acquisition of fusion competence. Viruses 2012, 4, 557–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, S.R.; Navas-Martin, S. Coronavirus pathogenesis and the emerging pathogen severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2005, 69, 635–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.F.; To, K.K.; Tse, H.; Jin, D.Y.; Yuen, K.Y. Interspecies transmission and emergence of novel viruses: Lessons from bats and birds. Trends Microbiol. 2013, 21, 544–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, M.V.T.; Ngo Tri, T.; Hong Anh, P.; Baker, S.; Kellam, P.; Cotton, M. Identification and characterization of Coronaviridae genomes from Vietnamese bats and rats based on conserved protein domains. Virus Evol. 2018, 4, vey035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammirati, E.; Wang, D.W. SARS-CoV-2 inflames the heart. The importance of awareness of myocardial injury in COVID-19 patients. Int. J. Cardiol. 2020, 311, 122–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Jin, H.; Wang, M.; Hu, Y.; Chen, S.; He, Q.; Chang, J.; Hong, C.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, D.; et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020, 77, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naicker, S.; Yang, C.W.; Hwang, S.J.; Liu, B.C.; Chen, J.H.; Jha, V. The Novel Coronavirus 2019 epidemic and kidneys. Kidney Int. 2020, 97, 824–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velavan, T.P.; Meyer, C.G. The COVID-19 epidemic. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2020, 25, 278–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Shi, L.; Wang, F.S. Liver injury in COVID-19: Management and challenges. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 5, 428–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drosten, C.; Günther, S.; Preiser, W.; van der Werf, S.; Brodt, H.R.; Becker, S.; Rabenau, H.; Panning, M.; Kolesnikova, L.; Fouchier, R.A.M.; et al. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 1967–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaki, A.M.; van Boheemen, S.; Bestebroer, T.M.; Osterhaus, A.D.; Fouchier, R.A.M. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 1814–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.C.; Shih, T.P.; Ko, W.C.; Tang, H.J.; Hsueh, P.R. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): The epidemic and the challenges. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 55, 105924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappello, F. Is COVID-19 a proteiform disease inducing also molecular mimicry phenomena? Cell Stress Chaperones 2020, 25, 381–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, C.; Sui, J.; Kuhn, J.H.; Moore, M.J.; Luo, S.; Wong, S.K.; Huang, I.C.; Xu, K.; Vasilieva, N.; et al. Receptor and viral determinants of SARS-coronavirus adaptation to human ACE2. EMBO J. 2005, 24, 1634–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyerholz, D.K.; Lambertz, A.M.; McCray, P.B., Jr. Dipeptidyl Peptidase 4 distribution in the human respiratory tract: Implications for the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome. Am. J. Pathol. 2016, 186, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sungnak, W.; Huang, N.; Bécavin, C.; Berg, M.; Queen, R.; Litvinukova, M.; Talavera-López, C.; Maatz, H.; Reichart, D.; Sampaziotis, F.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 entry factors are highly expressed in nasal epithelial cells together with innate immune genes. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macario, A.J.L.; Conway de Macario, E. Chapter 12—Chaperone proteins and chaperonopathies. In Stress: Physiology, Biochemistry, and Pathology; Fink, G., Ed.; Elsevier/Academic Press: London, UK, 2019; Volume 3, pp. 135–152. [Google Scholar]

- Macario, A.J.L.; Conwey de Macario, E. Molecular mechanisms in chaperonopathies: Clues to understanding the histopathological abnormalities and developing novel therapies. J. Pathol. 2020, 250, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahiya, V.; Buchner, J. Functional principles and regulation of molecular chaperones. Adv. Protein Chem. Struct. Biol. 2019, 114, 1–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macario, A.J.L. Heat-shock proteins and molecular chaperones: Implications for pathogenesis, diagnostics, and therapeutics. Int. J. Clin. Lab. Res. 1995, 25, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macario, A.J.L.; Conway de Macario, E. Sick chaperones, cellular stress, and disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 353, 1489–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macario, A.J.L.; Conway de Macario, E. Chaperonopathies by defect, excess, or mistake. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2007, 1113, 178–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panella, S.; Marcocci, M.E.; Celestino, I.; Valente, S.; Zwergel, C.; Li Puma, D.D.; Nencioni, L.; Mai, A.; Palamara, A.T.; Simonetti, G. MC1568 inhibits HDAC6/8 activity and influenza A virus replication in lung epithelial cells: Role of Hsp90 acetylation. Future Med. Chem. 2016, 8, 2017–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Q.; Song, D.; Li, H.; He, M.L. Stress proteins: The biological functions in virus infection, present and challenges for target-based antiviral drug development. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, P.L.; Hightower, L.E.; Hooper, P.L. Loss of stress response as a consequence of viral infection: Implications for disease and therapy. Cell Stress Chaperones 2012, 17, 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oglesbee, M.J.; Pratt, M.; Carsillo, T. Role for heat shock proteins in the immune response to measles virus infection. Viral Immunol. 2002, 15, 399–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, Y.; Kanai, F.; Kawakami, T.; Tateishi, K.; Ijichi, H.; Kawabe, T.; Arakawa, Y.; Kawakami, T.; Nishimura, T.; Shirakata, Y.; et al. Interaction of the hepatitis B virus X protein (HBx) with heat shock protein 60 enhances HBx-mediated apoptosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 318, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.M.; Kim, S.J.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, W.; Kim, G.W.; Lee, K.H.; Choi, K.Y.; Oh, J.W. Interaction of hepatitis C virus core protein with Hsp60 triggers the production of reactive oxygen species and enhances TNF-alpha-mediated apoptosis. Cancer Lett. 2009, 279, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrero, C.A.; Bouyssounade, D.; Zárate, S.; Isa, P.; López, T.; Espinosa, R.; Romero, P.; Méndez, E.; López, S.; Arias, C.F. Heat shock cognate protein 70 is involved in rotavirus cell entry. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 4096–4102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes-Del Valle, J.; Chávez-Salinas, S.; Medina, F.; Del Angel, R.M. Heat shock protein 90 and heat shock protein 70 are components of dengue virus receptor complex in human cells. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 4557–4567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongtan, T.; Wikan, N.; Wintachai, P.; Rattanarungsan, C.; Srisomsap, C.; Cheepsunthorn, P.; Smith, D.R. Characterization of putative Japanese encephalitis virus receptor molecules on microglial cells. J. Med. Virol. 2012, 84, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyżewski, Z.; Gregorczyk, K.P.; Szczepanowska, J.; Szulc-Dąbrowska, L. Functional role of Hsp60 as a positive regulator of human viral infection progression. Acta Virol. 2018, 62, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujhari, S.; Brustolin, M.; Macias, V.M.; Nissly, R.H.; Nomura, M.; Kuchipudi, S.V.; Rasgon, J.L. Heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) mediates Zika virus entry, replication, and egress from host cells. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2019, 8, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanovic, T.; Agosto, M.A.; Chandran, K.; Nibert, M.L. A role for molecular chaperone Hsc70 in reovirus outer capsid disassembly. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 12210–12219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.G.; Lee, S.M.; Jung, G. Antisense oligodeoxynucleotides targeted against molecular chaperonin Hsp60 block human hepatitis B virus replication. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 39851–39857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Mitra, D. Heat shock protein 40 is necessary for human immunodeficiency virus-1 Nef-mediated enhancement of viral gene expression and replication. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 40041–40050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okamoto, T.; Nishimura, Y.; Ichimura, T.; Suzuki, K.; Miyamura, T.; Suzuki, T.; Moriishi, K.; Matsuura, Y. Hepatitis C virus RNA replication is regulated by FKBP8 and Hsp90. EMBO J. 2006, 25, 5015–5025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, T.; Momose, F.; Kawaguchi, A.; Nagata, K. Involvement of Hsp90 in assembly and nuclear import of influenza virus RNA polymerase subunits. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 1339–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fislová, T.; Thomas, B.; Graef, K.M.; Fodor, E. Association of the influenza virus RNA polymerase subunit PB2 with the host chaperonin CCT. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 8691–8699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, M.; Rawat, P.; Khan, S.Z.; Dhamija, N.; Chaudhary, P.; Ravi, D.S.; Mitra, D. Reciprocal regulation of human immunodeficiency virus-1 gene expression and replication by heat shock proteins 40 and 70. J. Mol. Biol. 2011, 410, 944–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawashima, D.; Kanda, T.; Murata, T.; Saito, S.; Sugimoto, A.; Narita, Y.; Tsurumi, T. Nuclear transport of Epstein-Barr virus DNA polymerase is dependent on the BMRF1 polymerase processivity factor and molecular chaperone Hsp90. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 6482–6491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, B.; Miao, H.; Zohaib, A.; Xu, Q.; Chen, H.; Cao, S. Heat shock protein 70 is associated with replicase complex of Japanese encephalitis virus and positively regulates viral genome replication. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e75188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, X.; Zan, J.; Wu, Y.; Ye, C.; Ruan, X.; Zhou, J. Cellular chaperonin CCTγ contributes to rabies virus replication during infection. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 7608–7621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Ye, C.; Ruan, X.; Zan, J.; Xu, Y.; Liao, M.; Zhou, J. The chaperonin CCTα is required for efficient transcription and replication of rabies virus. Microbiol. Immunol. 2014, 58, 590–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batra, J.; Tripathi, S.; Kumar, A.; Katz, J.M.; Cox, N.J.; Lal, R.B.; Sambhara, S.; Lal, S.K. Human Heat shock protein 40 (Hsp40/DnaJB1) promotes influenza A virus replication by assisting nuclear import of viral ribonucleoproteins. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hafirassou, M.L.; Meertens, L.; Umaña-Diaz, C.; Labeau, A.; Dejarnac, O.; Bonnet-Madin, L.; Kümmerer, B.M.; Delaugerre, C.; Roingeard, P.; Vidalain, P.O.; et al. A global interactome map of the Dengue virus NS1 identifies virus restriction and dependency host factors. Cell Rep. 2017, 21, 3900–3913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchkovich, N.J.; Maguire, T.G.; Yu, Y.; Paton, A.W.; Paton, J.C.; Alwine, J.C. Human cytomegalovirus specifically controls the levels of the endoplasmic reticulum chaperone BiP/GRP78, which is required for virion assembly. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruri-Avidal, L.; López, S.; Arias, C.F. Endoplasmic reticulum chaperones are involved in the morphogenesis of rotavirus infectious particles. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 5368–5380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Khachatoorian, R.; Riahi, R.; Ganapathy, E.; Shao, H.; Wheatley, N.M.; Sundberg, C.; Jung, C.L.; Ruchala, P.; Dasgupta, A.; Arumugaswami, V.; et al. Allosteric heat shock protein 70 inhibitors block hepatitis C virus assembly. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2016, 47, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowlton, J.J.; de Castro, I.F.; Ashbrook, A.W.; Gestaut, D.R.; Zamora, P.F.; Bauer, J.A.; Forrest, J.C.; Frydman, J.; Risco, C.; Dermody, T.S. The TRiC chaperonin controls reovirus replication through outer-capsid folding. Nat. Microbiol. 2018, 3, 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Hendershot, L.M. ER chaperone functions during normal and stress conditions. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 2004, 28, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royle, J.; Ramírez-Santana, C.; Akpunarlieva, S.; Donald, C.L.; Gestuveo, R.J.; Anaya, J.M.; Merits, A.; Burchmore, R.; Kohl, A.; Varjak, M. Glucose-Regulated Protein 78 interacts with Zika virus envelope protein and contributes to a productive infection. Viruses 2020, 12, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, M. Endoplasmic reticulum stress responses. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2008, 65, 862–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, M.; Kaufman, R.J. The mammalian unfolded protein response. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2005, 74, 739–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumley, E.C.; Osborn, A.R.; Scott, J.E.; Scholl, A.G.; Mercado, V.; McMahan, Y.T.; Coffman, Z.G.; Brewster, J.L. Moderate endoplasmic reticulum stress activates a PERK and p38-dependent apoptosis. Cell Stress Chaperones 2017, 22, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.L.; Liao, C.L.; Lin, Y.L. Japanese encephalitis virus infection initiates endoplasmic reticulum stress and an unfolded protein response. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 4162–4171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Feng, Z.; He, B. Herpes simplex virus 1 infection activates the endoplasmic reticulum resident kinase PERK and mediates eIF-2alpha dephosphorylation by the gamma(1)34.5 protein. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 1379–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.A.; Schmechel, S.C.; Raghavan, A.; Abelson, M.; Reilly, C.; Katze, M.G.; Kaufman, R.J.; Bohjanen, P.R.; Schiff, L.A. Reovirus induces and benefits from an integrated cellular stress response. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 2019–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukrinsky, M.; Zhao, Y. Heat-shock proteins reverse the G2 arrest caused by HIV-1 viral protein R. DNA Cell Biol 2004, 23, 223–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iordanskiy, S.; Zhao, Y.; Dubrovsky, L.; Iordanskaya, T.; Chen, M.; Liang, D.; Bukrinsky, M. Heat shock protein 70 protects cells from cell cycle arrest and apoptosis induced by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 viral protein R. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 9697–9704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, D.; Benko, Z.; Agbottah, E.; Bukrinsky, M.; Zhao, R.Y. Anti-vpr activities of heat shock protein 27. Mol. Med. 2007, 13, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Song, R.; Lee, M.N.; Kim, C.S.; Lee, H.; Kong, Y.Y.; Kim, H.; Jang, S.K. A molecular chaperone glucose-regulated protein 94 blocks apoptosis induced by virus infection. Hepatology 2008, 47, 854–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, K.W.; Damania, B. Hsp90 and Hsp40/Erdj3 are required for the expression and anti-apoptotic function of KSHV K1. Oncogene 2010, 29, 3532–3544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neckers, L.; Tatu, U. Molecular chaperones in pathogen virulence: Emerging new targets for therapy. Cell Host Microbe 2008, 4, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pack, C.D.; Gierynska, M.; Rouse, B.T. An intranasal heat shock protein-based vaccination strategy confers protection against mucosal challenge with herpes simplex virus. Hum. Vaccin 2008, 4, 360–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, G.; Deng, T.; Fodor, E.; Leung, B.W.; Mayer, D.; Schwemmle, M.; Brownlee, G. Hsp90 inhibitors reduce influenza virus replication in cell culture. Virology 2008, 377, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.P.; Shan, G.Z.; Peng, Z.G.; Zhu, J.H.; Meng, S.; Zhang, T.; Gao, L.Y.; Tao, P.Z.; Gao, R.M.; Li, Y.H.; et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of heat-shock protein 90 inhibitors: Geldanamycin derivatives with broad antiviral activities. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 2010, 20, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.Y.; Oglesbee, M. Virus-heat shock protein interaction and a novel axis for innate antiviral immunity. Cells 2012, 1, 646–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Wunderink, R.G. MERS, SARS and other coronaviruses as causes of pneumonia. Respirology 2018, 23, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shereen, M.A.; Khan, S.; Kazmi, A.; Bashir, N.; Siddique, R. COVID-19 infection: Origin, transmission, and characteristics of human coronaviruses. J. Adv. Res. 2020, 24, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walls, A.C.; Park, Y.J.; Tortorici, M.A.; Wall, A.; McGuire, A.T.; Veesler, D. Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Cell 2020, 181, 281–292.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Schroeder, S.; Krüger, N.; Herrler, T.; Erichsen, S.; Schiergens, T.S.; Herrler, G.; Wu, N.H.; Nitsche, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell 2020, 181, 271–280.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, M.; Ruggiero, A.; Squeglia, F.; Maga, G.; Berisio, R. A structural view of SARS-CoV-2 RNA replication machinery: RNA synthesis, proofreading and final capping. Cells 2020, 9, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Moore, M.J.; Vasilieva, N.; Sui, J.; Wong, S.K.; Berne, M.A.; Somasundaran, M.; Sullivan, J.L.; Luzuriaga, K.; Greenough, T.C.; et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature 2003, 426, 450–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, I.M.; Abdelmalek, D.H.; Elshahat, M.E.; Elfiky, A.A. COVID-19 spike-host cell receptor GRP78 binding site prediction. J. Infect. 2020, 80, 554–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belouzard, S.; Millet, J.K.; Licitra, B.N.; Whittaker, G.R. Mechanisms of coronavirus cell entry mediated by the viral spike protein. Viruses 2012, 4, 1011–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Hendershot, L.M. The mammalian endoplasmic reticulum as a sensor for cellular stress. Cell Stress Chaperones 2002, 7, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.; Chan, C.M.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, S.; Zhou, J.; Au-Yeung, R.K.H.; Sze, K.H.; Yang, D.; Shuai, H.; et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus and bat coronavirus HKU9 both can utilize GRP78 for attachment onto host cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 11709–11726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rainbolt, T.K.; Saunders, J.M.; Wiseman, R.L. Stress-responsive regulation of mitochondria through the ER unfolded protein response. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 25, 528–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.C.; Jou, M.J.; Huang, S.Y.; Li, S.W.; Wan, L.; Tsai, F.J.; Lin, C.W. Proteomic analysis of up-regulated proteins in human promonocyte cells expressing severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 3C-like protease. Proteomics 2007, 7, 1446–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukushi, M.; Yoshinaka, Y.; Matsuoka, Y.; Hatakeyama, S.; Ishizaka, Y.; Kirikae, T.; Sasazuki, T.; Miyoshi-Akiyama, T. Monitoring of S protein maturation in the endoplasmic reticulum by calnexin is important for the infectivity of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 11745–11753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wit, E.; van Doremalen, N.; Falzarano, D.; Munster, V.J. SARS and MERS: Recent insights into emerging coronaviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Chen, F.; Ye, S.; Guo, X.; Muhanmmad Memon, A.; Wu, M.; He, Q. Comparative proteome analysis of porcine jejunum tissues in response to a virulent strain of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus and its attenuated strain. Viruses 2016, 8, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, X.; Xu, P.; Wu, X.; Zhou, L.; Wang, H. Heat shock protein 70 in lung and kidney of specific-pathogen-free chickens is a receptor-associated protein that interacts with the binding domain of the spike protein of infectious bronchitis virus. Arch. Virol. 2017, 162, 1625–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaheen, A. Effect of the unfolded protein response on ER protein export: A potential new mechanism to relieve ER stress. Cell Stress Chaperones 2018, 23, 797–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoe, T. Pathological aspects of COVID-19 as a conformational disease and the use of pharmacological chaperones as a potential therapeutic strategy. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, C.P.; Siu, K.L.; Chin, K.T.; Yuen, K.Y.; Zheng, B.; Jin, D.Y. Modulation of the unfolded protein response by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 9279–9287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, C.S.; Nabar, N.R.; Huang, N.N.; Kehrl, J.H. SARS-Coronavirus Open Reading Frame-8b triggers intracellular stress pathways and activates NLRP3 inflammasomes. Cell Death Discov. 2019, 5, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isler, J.A.; Maguire, T.G.; Alwine, J.C. Production of infectious human cytomegalovirus virions is inhibited by drugs that disrupt calcium homeostasis in the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 15388–15397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uhal, B.D.; Nguyen, H.; Dang, M.; Gopallawa, I.; Jiang, J.; Dang, V.; Ono, S.; Morimoto, K. Abrogation of ER stress-induced apoptosis of alveolar epithelial cells by angiotensin 1-7. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2013, 305, L33–L41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhang, M.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, W.; Yu, G.; Jin, F. ACE-2/ANG1-7 ameliorates ER stress-induced apoptosis in seawater aspiration-induced acute lung injury. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2018, 315, L1015–L1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, M.; Zhang, Y.; Lee, A.S. Beyond the endoplasmic reticulum: Atypical GRP78 in cell viability, signalling and therapeutic targeting. Biochem. J. 2011, 434, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.S. Glucose-regulated proteins in cancer: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, T.; Horie, M.; Daito, T.; Ikuta, K.; Tomonaga, K. Molecular chaperone BiP interacts with Borna disease virus glycoprotein at the cell surface. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 12622–12625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumla, A.; Chan, J.F.; Azhar, E.I.; Hui, D.S.; Yuen, K.Y. Coronaviruses—Drug discovery and therapeutic options. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2016, 15, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Báez-Santos, Y.M.; St John, S.E.; Mesecar, A.D. The SARS-coronavirus papain-like protease: Structure, function and inhibition by designed antiviral compounds. Antiviral Res. 2015, 115, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.W.; Lin, K.H.; Hsieh, T.H.; Shiu, S.Y.; Li, J.Y. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 3C-like protease-induced apoptosis. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2006, 46, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, P.D.; Wang, R.Y.; Pogany, J.; Hafren, A.; Makinen, K. Emerging picture of host chaperone and cyclophilin roles in RNA virus replication. Virology 2011, 411, 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutta, D.; Bagchi, P.; Chatterjee, A.; Nayak, M.K.; Mukherjee, A.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Nagashima, S.; Kobayashi, N.; Komoto, S.; Taniguchi, K.; et al. The molecular chaperone heat shock protein-90 positively regulates rotavirus infection. Virology 2009, 391, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geller, R.; Taguwa, S.; Frydman, J. Broad action of Hsp90 as a host chaperone required for viral replication. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1823, 698–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakovac, H. COVID-19 and hypertension—Is the HSP60 culprit for the severe course and worse outcome? Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2020, 319, H793–H796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, M.P. Recruitment of Hsp70 chaperones: A crucial part of viral survival strategies. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2005, 153, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.J.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, C.H.; Ahn, Y.J.; Song, J.H.; Baek, S.H.; Kwon, D.H. Antiviral activity of quercetin 7-rhamnoside against porcine epidemic diarrhea virus. Antivir. Res. 2009, 81, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.Y.; Lee, S.; Cyr, D.M. Mechanisms for regulation of Hsp70 function by Hsp40. Cell Stress Chaperones 2008, 8, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.; Danda, D.; Kavadichanda, C.; Das, S.; Adarsh, M.B.; Negi, V.S. Autoimmune and rheumatic musculoskeletal diseases as a consequence of SARS-CoV-2 infection and its treatment. Rheumatol. Int. 2020, 40, 1539–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappello, F.; Marino Gammazza, A.; Dieli, F.; Conway de Macario, E.; Macario, A.J.L. Does SARS-CoV-2 trigger stress-induced autoimmunity by molecular mimicry? A hypothesis. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marino Gammazza, A.; Légaré, S.; Lo Bosco, G.; Fucarino, A.; Angileri, F.; Conway de Macario, E.; Macario, A.J.L.; Cappello, F. Human molecular chaperones share with SARS-CoV-2 antigenic epitopes potentially capable of eliciting autoimmunity against endothelial cells: Possible role of molecular mimicry in COVID-19. Cell Stress Chaperones 2020, 25, 737–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ackermann, M.; Verleden, S.E.; Kuehnel, M.; Haverich, A.; Welte, T.; Laenger, F.; Vanstapel, A.; Werlein, C.; Stark, H.; Tzankov, A.; et al. Pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucchese, G.; Flöel, A. SARS-CoV-2 and Guillain-Barré syndrome: Molecular mimicry with human heat shock proteins as potential pathogenic mechanism. Cell Stress Chaperones 2020, 25, 731–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappello, F.; Marino Gammazza, A.; Palumbo Piccionello, A.; Campanella, C.; Pace, A.; Conway de Macario, E.; Macario, A.J.L. Hsp60 chaperonopathies and chaperonotherapy: Targets and agents. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2014, 18, 185–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusaczuk, M. Tauroursodeoxycholate-Bile acid with chaperoning activity: Molecular and cellular effects and therapeutic perspectives. Cells 2019, 8, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rellmann, Y.; Gronau, I.; Hansen, U.; Dreier, R. 4-Phenylbutyric acid reduces endoplasmic reticulum stress in chondrocytes that is caused by loss of the protein disulfide isomerase ERp57. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2019, 2019, 6404035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, M.; Restrepo-Jiménez, P.; Monsalve, D.M.; Pacheco, Y.; Acosta-Ampudia, Y.; Ramírez-Santana, C.; Leung, P.; Ansari, A.A.; Gershwin, M.E.; Anaya, J.M. Molecular mimicry and autoimmunity. J. Autoimmun. 2018, 95, 100–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smatti, M.K.; Cyprian, F.S.; Nasrallah, G.K.; Al Thani, A.A.; Almishal, R.O.; Yassine, H.M. Viruses and Autoimmunity: A Review on the Potential Interaction and Molecular Mechanisms. Viruses 2019, 11, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).