Sexual Dysfunction and Quality of Life in Chronic Heroin-Dependent Individuals on Methadone Maintenance Treatment

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

3. Results

3.1. Clinical and Sociodemographic Characteristics of Patients

Differences between Sexes in Clinical and Sociodemographic Characteristics

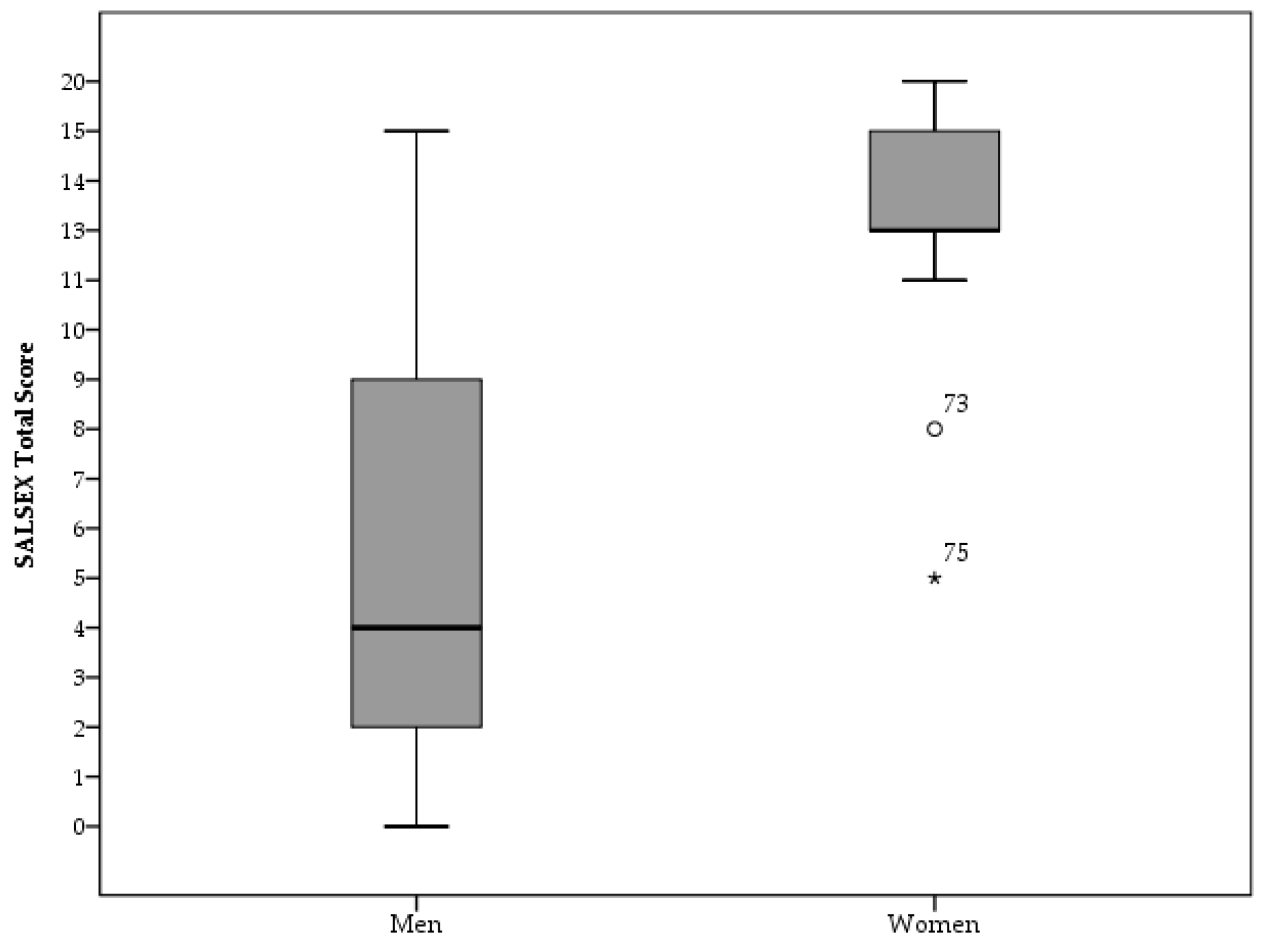

3.2. Sexual Activity, Frequency of SD and Group Differences in SALSEX Scores

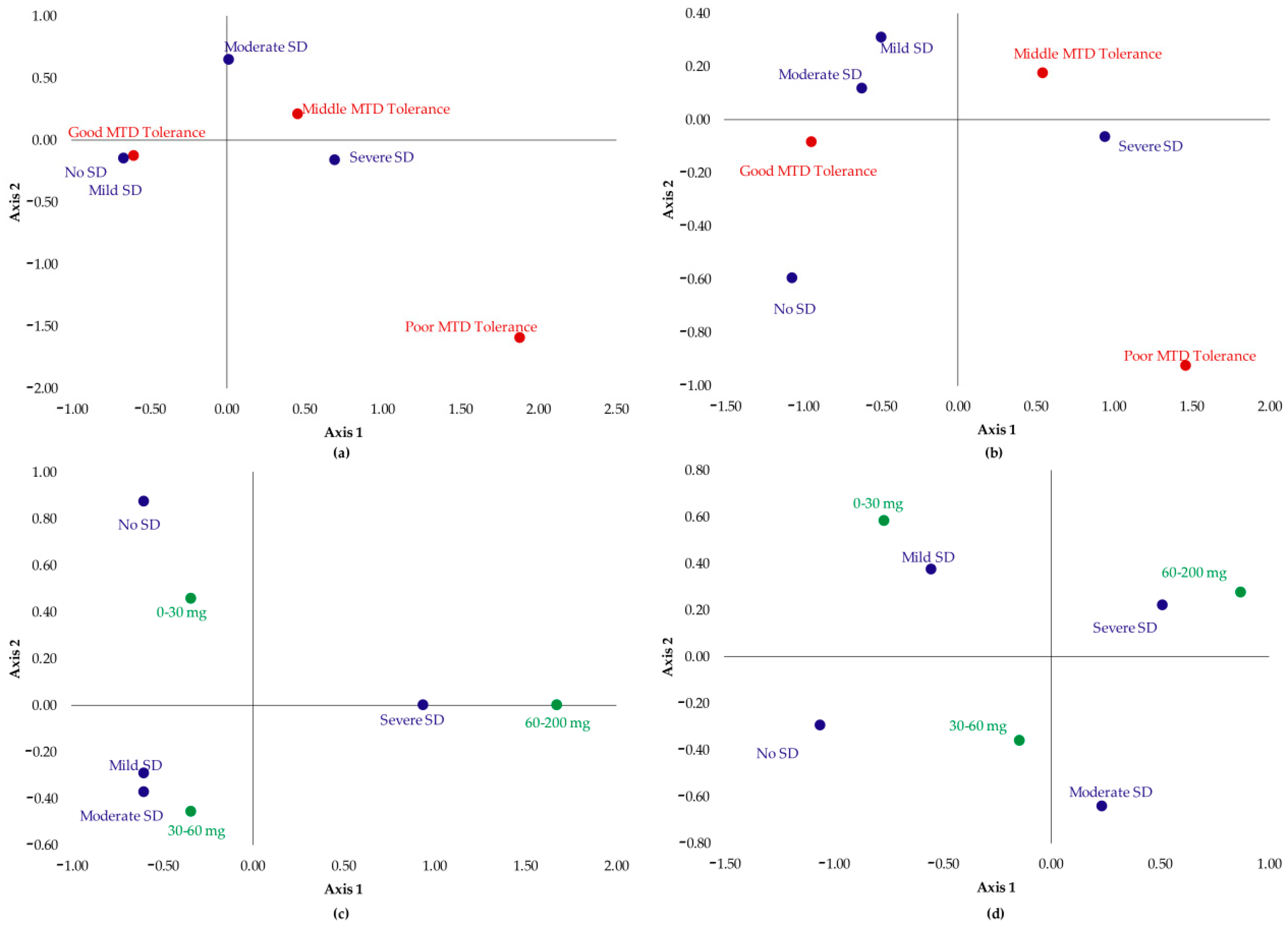

Impact of Treatment Duration, Methadone Dose Consumed, Tolerance toward Methadone, and Effect of Using Benzodiazepines on Sexual Dysfunction

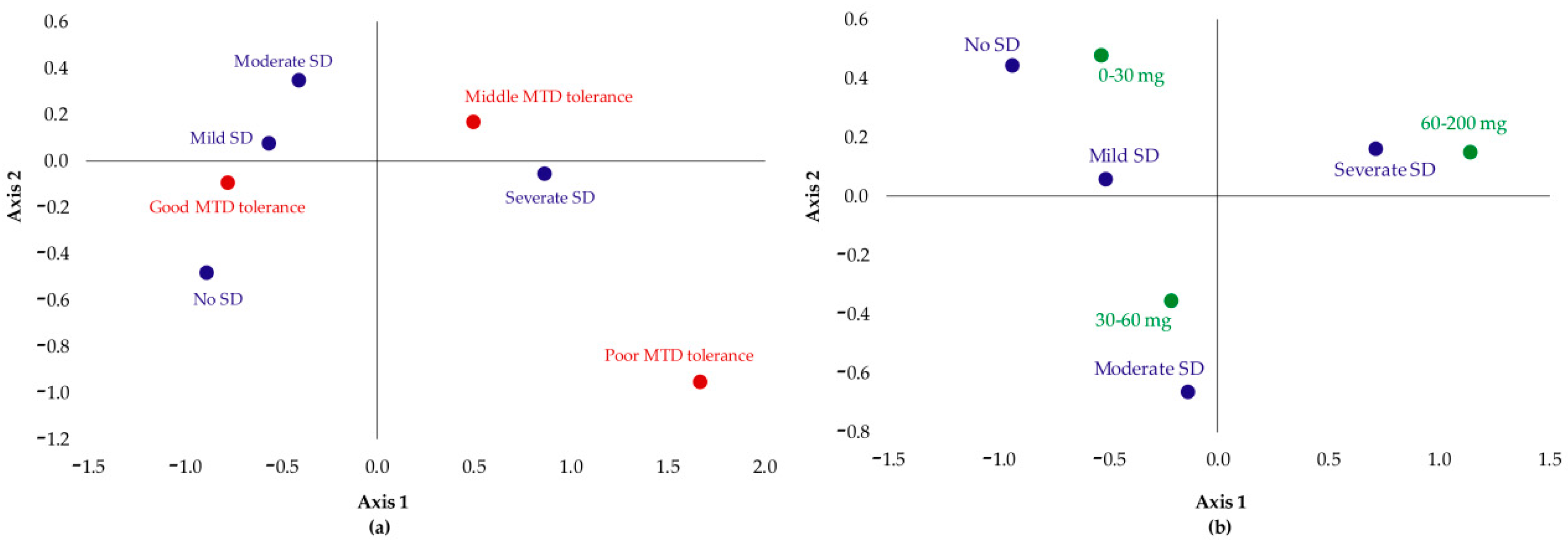

- Patients which had no SD or their SD was not severe showed good tolerance to MTD;

- Patients with moderate SD were those that had good or medium tolerance;

- Severe SD was associated with poor MTD tolerance.

- Patients which had no SD or their SD was mild were those who took a dose between 0 and 30 mg;

- Patients with moderate SD took 30–60 mg of MTD;

- Severe SD was associated with the highest doses: 60–200 mg.

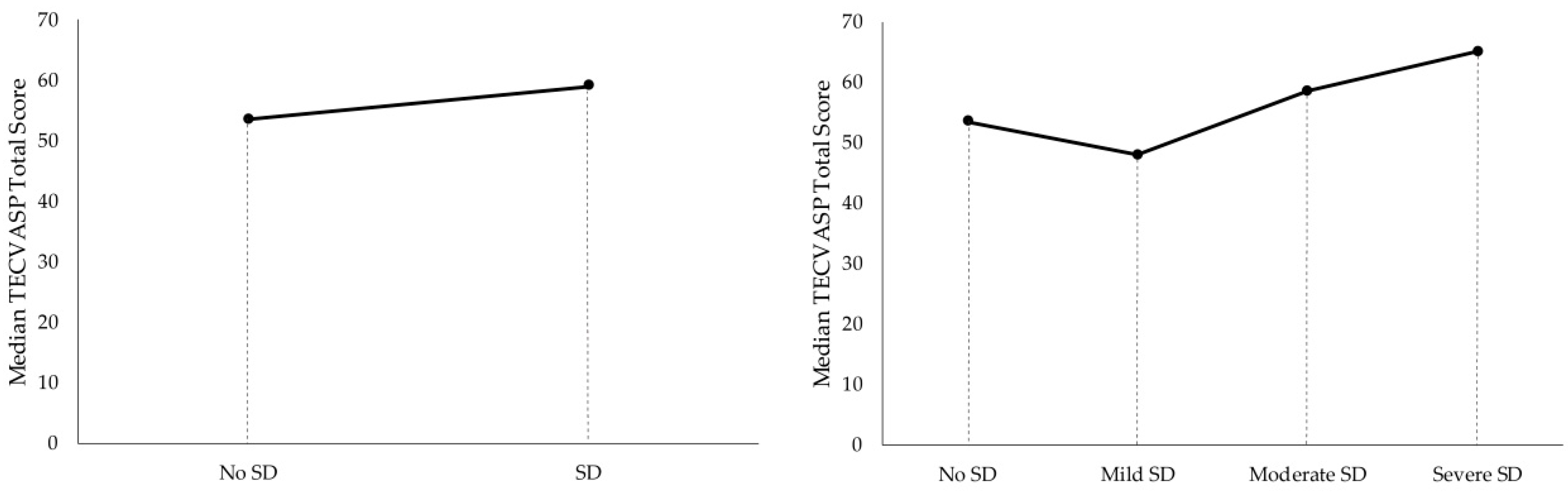

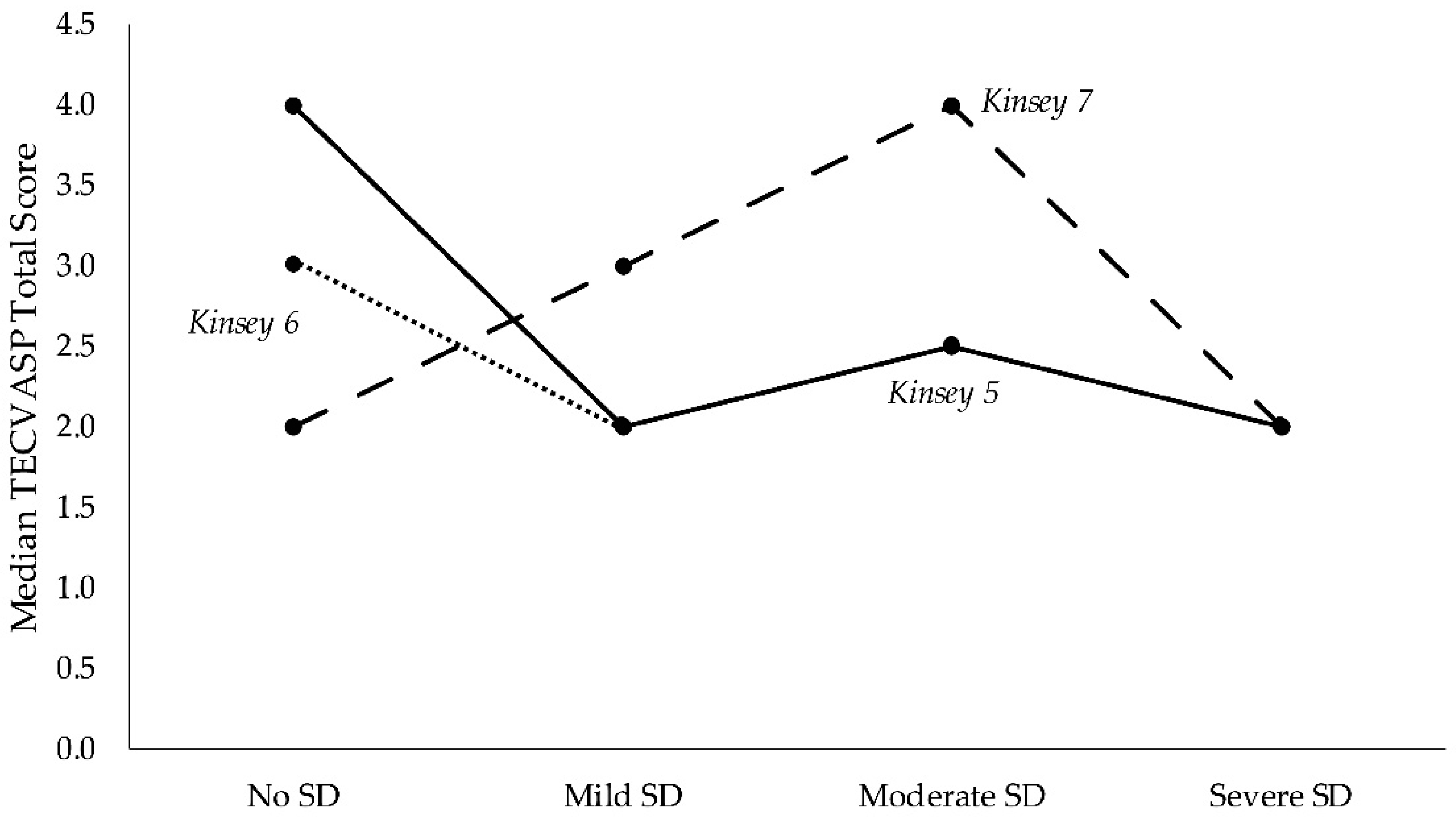

3.3. Quality of Life in Presence of Sexual Dysfunction Problems

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Degenhardt, L.; Charlson, F.; Mathers, B.; Hall, W.D.; Flaxman, A.D.; Johns, N.; Vos, T. The global epidemiology and burden of opioid dependence: Results from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Addiction 2014, 109, 1320–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattick, R.P.; Breen, C.; Kimber, J.; Davoli, M. Methadone maintenance therapy versus no opioid replacement therapy for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009, 3, CD002209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattick, R.P.; Breen, C.; Kimber, J.; Davoli, M. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 2, CD002207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Degenhardt, L.; Randall, D.; Hall, W.; Law, M.; Butler, T.; Burns, L. Mortality among clients of a state-wide opioid pharmacotherapy program over 20 years: Risk factors and lives saved. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009, 105, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallinan, R.; Byrne, A.; Agho, K.; McMahon, C.; Tynan, P.; Attia, J. Erectile dysfunction in men receiving methadone and buprenorphine maintenance treatment. J. Sex. Med. 2008, 5, 684–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yee, A.; Loh, H.S.; Ng, C.G. The prevalence of sexual dysfunction among male patients on methadone and buprenorphine treatments: A meta-analysis study. J. Sex. Med. 2014, 11, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matuszewich, L.; Ormsby, J.L.; Moses, J.; Lorrain, D.S.; Hull, E.M. Effects of morphiceptin in the medial preoptic area on male sexual behavior. Psychopharmacology 1995, 122, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argiolas, A.; Melis, M.R. Neuropeptides and central control of sexual behaviour from the past to the present: A review. Prog Neurobiol. 2013, 108, 80–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Y.; Zhang, D.; Li, X.; Chen, W.; He, Q.; Jahn, H.J.; Li, X.; Chen, J.; Hu, P.; Ling, L. Sexual dysfunction during methadone maintenance treatment and its influence on patient’s life and treatment: A qualitative study in South China. Psychol. Health Med. 2013, 18, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reno, R.R.; Aiken, L.S. Life activities and life quality of heroin addicts in and out of methadone treatment. Int. J. Addict. 1993, 28, 211–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, R.; Balousek, S.; Mundt, M.; Fleming, M. Methadone maintenance and male sexual dysfunction. J. Addict. Dis. 2005, 24, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinsey, A.C.; Pomeroy, W.R.; Martin, C.E. Sexual Behavior in the Human Male. Am. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 894–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montejo, A.L.; Llorca, G.; Izquierdo, J.A.; Rico-Villademoros, F. Incidence of sexual dysfunction associated with antidepressant agents: A prospective multicenter study of 1022 outpatients. Spanish Working Group for the Study of Psychotropic-Related Sexual Dysfunction. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2001, 62 (Suppl. 3), 10–21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Montejo, A.L.; Rico-Villademoros, F. Psychometric properties of the Psychotropic-Related Sexual Dysfunction Questionnaire (PRSexDQ-SALSEX) in patients with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2008, 34, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lozano Rojas, O.M.; Rojas Tejada, A.J.; Pérez Meléndez, C. Development of a specific health-related quality of life test in drug abusers using the Rasch rating scale model. Eur. Addict. Res. 2009, 15, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, H.; Shi, C.X.; McGoogan, J.M.; Zhang, B.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, M.; Rou, K.; Wu, Z. Sexual dysfunction improved in heroin-dependent men after methadone maintenance treatment in Tianjin, China. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e88289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quaglio, G.; Lugoboni, F.; Pattaro, C.; Melara, B.; Mezzelani, P.; Des Jarlais, D.C. Erectile dysfunction in male heroin users, receiving methadone and buprenorphine maintenance treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008, 94, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grover, S.; Mattoo, S.K.; Pendharkar, S.; Kandappan, V. Sexual dysfunction in patients with alcohol and opioid dependence. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2014, 36, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yee, A.; Loh, H.S.; Ng, C.G.; Sulaiman, A.H. Sexual Desire in Opiate-Dependent Men Receiving Methadone-Assisted Treatment. Am. J. Mens Health 2018, 12, 1016–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanbury, R.; Cohen, M.; Stimmel, B. Adequacy of sexual performance in men maintained on methadone. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse 1977, 4, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaafar, N.R.N.; Mislan, N.; Aziz, S.A.; Baharudin, A.; Ibrahim, N.; Midin, M.; Das, S.; Sidi, H. Risk Factors of Erectile Dysfunction in Patients Receiving Methadone Maintenance Therapy. J. Sex. Med. 2013, 10, 2069–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerra, G.; Manfredini, M.; Somaini, L.; Maremmani, I.; Leonardi, C.; Donnini, C. Sexual Dysfunction in Men Receiving Methadone Maintenance Treatment: Clinical History and Psychobiological Correlates. Eur. Addict. Res. 2016, 22, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trajanovska, A.S.; Vujovic, V.; Ignjatova, L.; Janicevic-Ivanovska, D.; Cibisev, A. Sexual dysfunction as a side effect of hyperprolactinemia in methadone maintenance therapy. Med. Arch Sarajevo Bosnia Herzeg 2013, 67, 48–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinta Gomes, A.L.; Nobre, P. Personality traits and psychopathology on male sexual dysfunction: An empirical study. J. Sex. Med. 2011, 8, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crisp, C.C.; Vaccaro, C.M.; Pancholy, A.; Kleeman, S.; Fellner, A.N.; Pauls, R. Is female sexual dysfunction related to personality and coping? An exploratory study. Sex. Med. 2013, 1, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, B.-L.; Xu, Y.-M.; Zhu, J.-H.; Li, H.-J. Sexual life satisfaction of methadone-maintained Chinese patients: Individuals with pain are dissatisfied with their sex lives. J. Pain Res. 2018, 11, 1789–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uhde, T.W.; Tancer, M.E.; Shea, C.A. Sexual dysfunction related to alprazolam treatment of social phobia. Am, J. Psychiatry. abril de 1988, 145, 531–532. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzilli, R.; Angeletti, G.; Olana, S.; Delfino, M.; Zamponi, V.; Rapinesi, C.; Del Casale, A.; Kotzalidis, G.D.; Elia, J.; Callovini, G.; et al. Erectile dysfunction in patients taking psychotropic drugs and treated with phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors. Arch. Ital. Urol. Androl. 2018, 90, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montejo-González, A.L.; Llorca, G.; Izquierdo, J.A.; Ledesma, A.; Bousoño, M.; Calcedo, A.; Carrasco, J.L.; Ciudad, J.; Daniel, E.; De la Gandara, J. SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction: Fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, and fluvoxamine in a prospective, multicenter, and descriptive clinical study of 344 patients. J. Sex Marital Ther. 1997, 23, 176–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | N = 85 |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 43.1 ± 7.7 |

| <30 years, n (%) | 6 (7.1) |

| 30–40, n (%) | 22 (25.9) |

| 40–50, n (%) | 45 (52.9) |

| >50, n (%) | 12 (14.1) |

| Sex (males), n (%) | 72 (84.7) |

| Treatment time (years) | 7.21 ± 6.95 |

| MTD 1 dose | 49.01 ± 29.87 |

| MTD 1 tolerance | |

| Good tolerance, n (%) | 37 (43.5) |

| Middle tolerance, n (%) | 44 (51.8) |

| Poor tolerance, n (%) | 4 (4.7) |

| Personality disorder, n (%) | 49 (57.6) |

| Consumption of self-administered benzodiazepines, n (%) | 27 (31.8) |

| Dose (mg) | 95.19 ± 98.45 |

| Consumption of medicated benzodiazepines, n (%) | 22 (25.9%) |

| Dose (mg) | 36.36 ± 32.74 |

| Characteristic | Men (n = 72) | Women (n = 13) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 42.76 ± 7.79 | 46 ± 15.5 | 0.49 |

| Treatment time (years) | 6.74 ± 6.74 | 9 ± 17.5 | 0.01 |

| MTD’ dose (mg) | 45.33 ± 25.29 | 60 ± 23.5 | 0.20 |

| MTD’s tolerance | - | - | 0.01 |

| Good tolerance, n (%) | 35 (48.6) | 2 (15.4) | |

| Middle tolerance, n (%) | 35 (48.6) | 9 (69.2) | |

| Poor tolerance, n (%) | 2 (2.8) | 2 (15.4) | |

| Personality disorder, n (%) | 41 (56.9) | 8 (61.5) | 0.77 |

| Dose of self-administered benzodiazepines (mg) | 96.46 ± 103.78 | 85 ± 44.44 | 0.74 |

| Dose of medicated benzodiazepines (mg) | 40 ± 36.52 | 20 ± 40.0 | 0.59 |

| Characteristic | No SD Patients (n = 12) | SD Patients (n = 73) | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild (n = 21) | Moderate (n = 18) | Severe (n = 34) | |||

| Age (years) | 44 ± 9.75 | 43 ± 11 | 45.5 ± 10 | 42.5 ± 10.5 | 0.871 |

| MTD’s dose (mg) | 32.5 ± 13.75 | 40 ± 28 | 39 ± 18.75 | 53 ± 40.75 | 0.005 |

| MTD’s tolerance | |||||

| Good tolerance, n (%) | 9 (75) | 13 (61.9) | 10 (55.6) | 5 (14.7) | 0.000 |

| Medium tolerance, n (%) | 3 (25) | 8 (38.1) | 8 (44.4) | 25 (73.5) | |

| Poor tolerance, n (%) | - | - | - | 4 (11.8) | |

| Personality disorder, n (%) | 8 (66.7) | 11 (52.4) | 10 (55.6) | 20 (58.8) | 0.947 |

| Characteristic | No SD Patients (n = 12) | Mild SD Patients (n = 21) | Moderate/Severe SD Patients (n = 52) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DL | DEO | A | ELP | DL | DEO | A | ELP | ||

| MTD dose | |||||||||

| <30 mg | 0 | 87.5 | 75 | 12.5 | 50 | 100 | 72.7 | 54.5 | 81.8 |

| 30–60 mg | 0 | 72.7 | 72.7 | 18.2 | 27.3 | 95.8 | 79.2 | 83.3 | 83.3 |

| >60 mg | - | 0 | 100 | 50 | 0 | 94.1 | 94.1 | 88.2 | 94.1 |

| MTD tolerance | |||||||||

| Poor | - | - | - | - | - | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Medium | 0 | 62.5 | 75 | 0 | 12.5 | 93.9 | 87.9 | 87.9 | 87.9 |

| Good | 0 | 76.9 | 76.9 | 30.8 | 46.2 | 93.3 | 66.6 | 53.3 | 80 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Llanes, C.; Álvarez, A.I.; Pastor, M.T.; Garzón, M.Á.; González-García, N.; Montejo, Á.L. Sexual Dysfunction and Quality of Life in Chronic Heroin-Dependent Individuals on Methadone Maintenance Treatment. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 321. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8030321

Llanes C, Álvarez AI, Pastor MT, Garzón MÁ, González-García N, Montejo ÁL. Sexual Dysfunction and Quality of Life in Chronic Heroin-Dependent Individuals on Methadone Maintenance Treatment. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2019; 8(3):321. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8030321

Chicago/Turabian StyleLlanes, Carlos, Ana I. Álvarez, M. Teresa Pastor, M. Ángeles Garzón, Nerea González-García, and Ángel L. Montejo. 2019. "Sexual Dysfunction and Quality of Life in Chronic Heroin-Dependent Individuals on Methadone Maintenance Treatment" Journal of Clinical Medicine 8, no. 3: 321. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8030321

APA StyleLlanes, C., Álvarez, A. I., Pastor, M. T., Garzón, M. Á., González-García, N., & Montejo, Á. L. (2019). Sexual Dysfunction and Quality of Life in Chronic Heroin-Dependent Individuals on Methadone Maintenance Treatment. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 8(3), 321. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8030321