The Co-Occurrence of Sexsomnia, Sleep Bruxism and Other Sleep Disorders

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Sexsomnia and Obstructive Sleep Apnea/Hypopnea

3.2. Sexsomnia and Sleep-Related Eating Disorder

3.3. Sexsomnia and Sleepwalking

3.4. Sexsomnia and Multiple Various Sleep-Related Disorders

3.5. Co-Occurrence of Sexsomnia, Sleep Bruxism and Other Sleep-Related Disorders

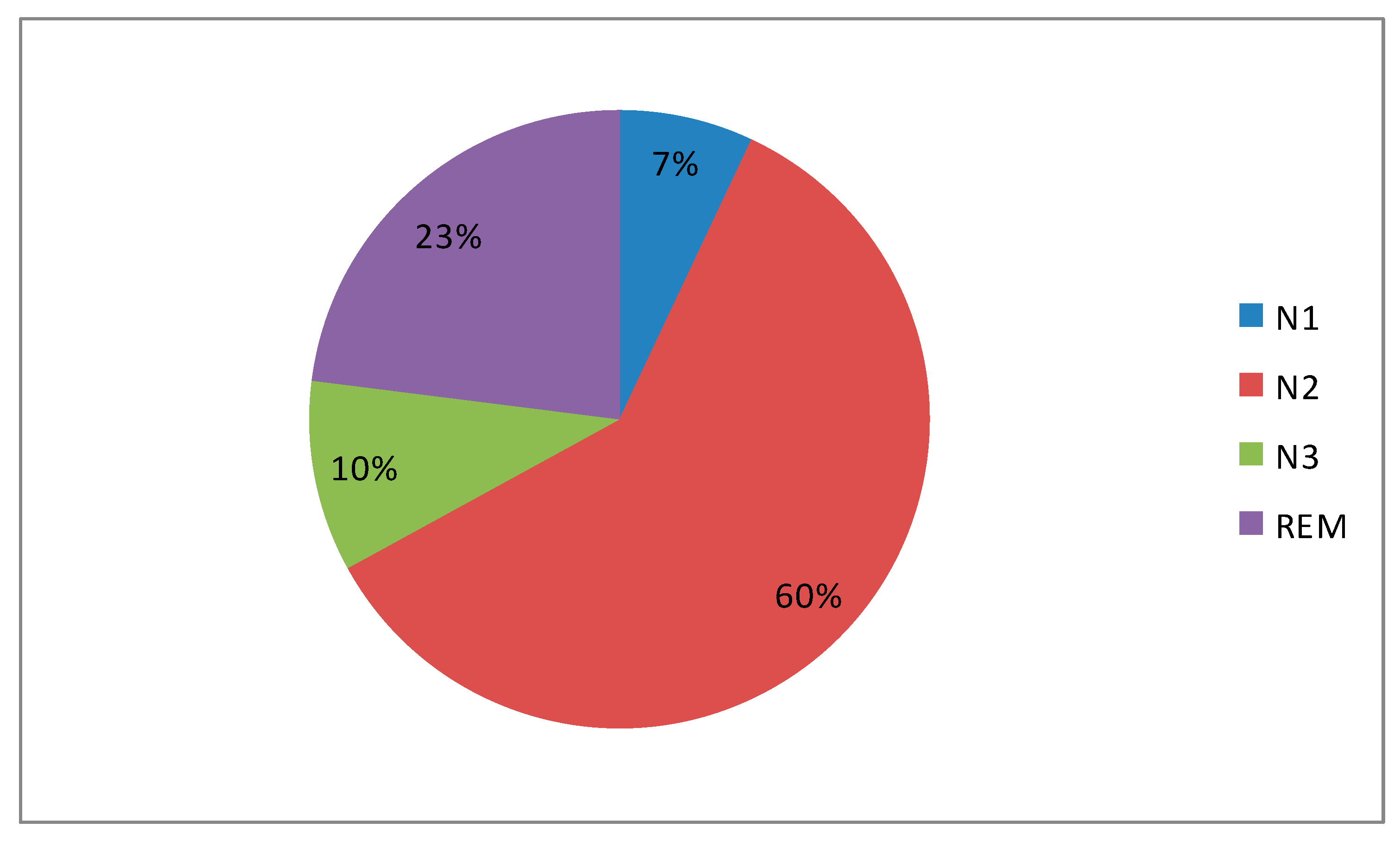

3.5.1. Case 1

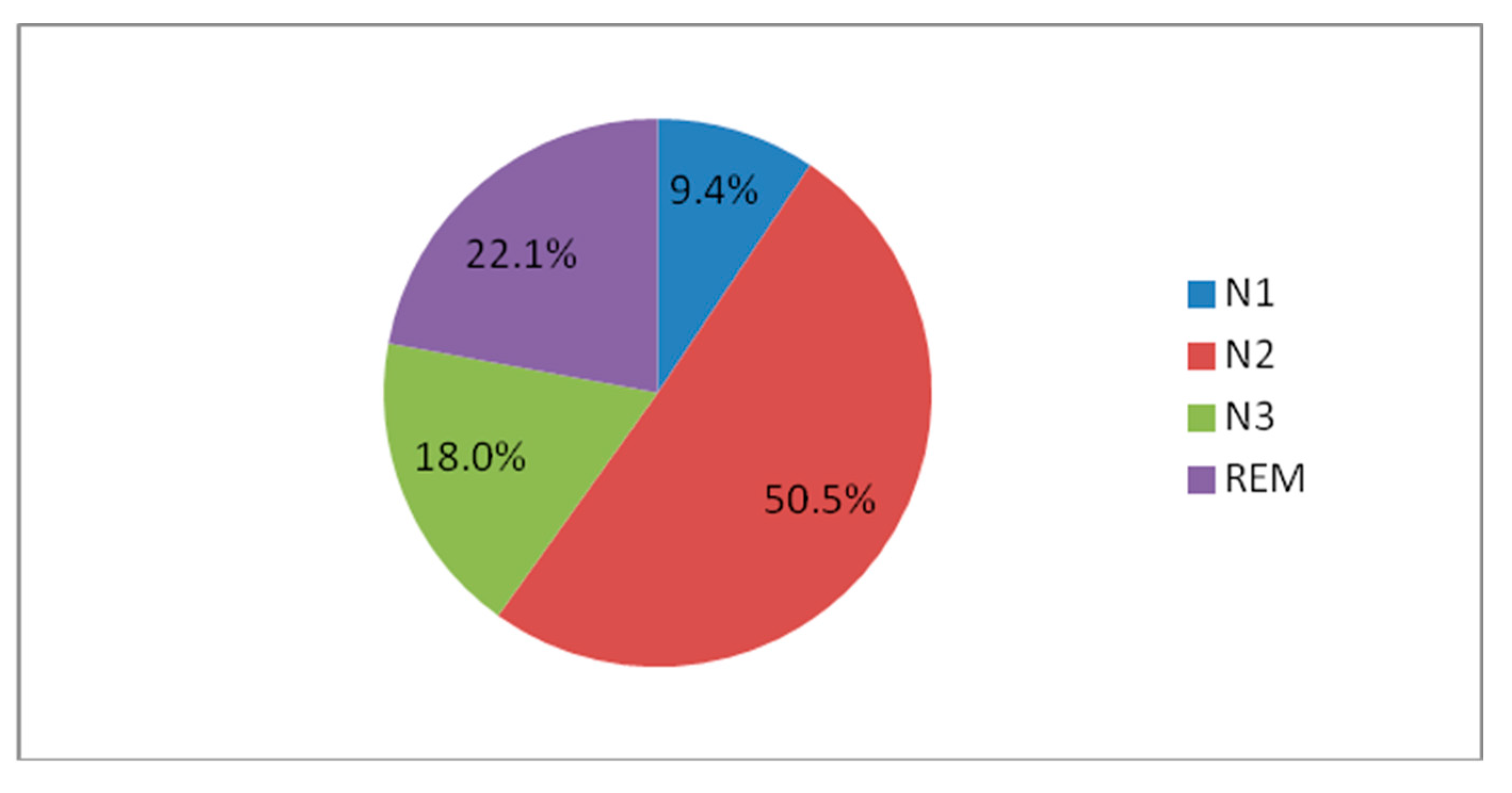

3.5.2. Case 2

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fleetham, J.A.; Fleming, J.A. Parasomnias. CMAJ 2014, 186, E273–E280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 3rd ed.; American Academy of Sleep Medicine: Darien, IL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. In DSM-5, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zucconi, M.; Ferri, R. Classification of Sleep Disorders. In Sleep Medicine Textbook; European Sleep Research Society: Regensburg, Germany, 2014; pp. 95–109. [Google Scholar]

- Muza, R.; Lawrence, M.; Drakatos, P. The reality of sexsomnia. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2016, 22, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organ, A.; Fedoroff, J.P. Sexsomnia: Sleep sex research and its legal implications. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2015, 17, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, M.L.; Poyares, D.; Alves, R.S.; Skomro, R.; Tufik, S. Sexsomnia: Abnormal sexual behavior during sleep. Brain Res. Rev. 2007, 56, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebrahim, I.O. Somnambulistic sexual behaviour (sexsomnia). J. Clin. Forensic Med. 2006, 13, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schenck, C.H.; Arnulf, I.; Mahowald, M.W. Sleep and sex: What can go wrong? A review of the literature on sleep related disorders and abnormal sexual behaviors and experiences. Sleep 2007, 30, 683–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomis Devesa, A.J.; Ortega Albás, J.J.; Denisa Ghinea, A.; Carratalá Monfort, S. Sexsomnia and sleep eating secondary to sodium oxybate consumption. Neurologia 2016, 31, 355–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ariño, H.; Iranzo, A.; Gaig, C.; Santamaria, J. Sexsomnia: Parasomnia associated with sexual behaviour during sleep. Neurologia 2014, 29, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Béjot, Y.; Juenet, N.; Garrouty, R.; Maltaverne, D.; Nicolleau, L.; Giroud, M.; Didi-Roy, R. Sexsomnia: An uncommon variety of parasomnia. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2010, 112, 72–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krol, D.G. Sexsomnia during treatment with a selectiveserotonin reuptake inhibitor. Tijdschr. Psychiatr. (J. Psychiatry) 2008, 50, 735–739. [Google Scholar]

- Meira, E.; Cruz, M.; Soca, R. Sexsomnia and REM—Predominant obstructive sleep apnea effectively treated with a mandibular advancement device. Sleep Sci. 2016, 9, 140–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khawaja, I.S.; Hurwitz, T.D.; Schenck, C.H. Sleep-related abnormal sexual behavior (sexsomnia) successfully treated with a mandibular advancement device: A case report. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2017, 13, 627–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schenck, C.H.; Mahowald, M.W. Parasomnias Associated with sleep-disordered breathing and its therapy, including sexsomnia as a recently recognized parasomnia. Somnologie 2008, 12, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Marca, G.; Dittoni, S.; Frusciante, R.; Colicchio, S.; Losurdo, A.; Testani, E.; Buccarella, C.; Modoni, A.; Mazza, S.; Mennuni, G.F.; et al. Abnormal sexual behavior during sleep. J. Sex. Med. 2009, 6, 3490–3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, Y. Sleep-related eating disorder and its associated conditions. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2015, 69, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, S.B.; Schenck, C.H. Sexsomnia: A case of sleep masturbation documented by video-polysomnography in a young adult male with sleepwalking. Sleep Sci. 2016, 9, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soca, R.; Keenan, J.C.; Schenck, C.H. Parasomnia overlap disorder with sexual behaviors during sleep in a patient with obstructive sleep apnea. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2016, 12, 1189–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelin, Z.; Yazla, E. Abnormal sexual behavior during sleep in temporal lobe epilepsy: A case report. Balkan Med. J. 2012, 29, 211–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicolin, A.; Tribolo, A.; Giordano, A.; Chiarot, E.; Peila, E.; Terreni, A.; Bucca, C.; Mutani, R. Sexual behaviors during sleep associated with polysomnographically confirmed parasomnia overlap disorder. Sleep Med. 2011, 12, 523–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, C.M.; Trajanovic, N.N.; Fedoroff, J.P. Sexsomnia—A new parasomnia? Can. J. Psychiatry 2003, 48, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irfan, M.; Schenck, C.H. Sleep-related orgasms in a 57-year-old woman: A case report. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2018, 14, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mioč, M.; Antelmi, E.; Filardi, M.; Pizza, F.; Ingravallo, F.; Nobili, L.; Tassinari, C.A.; Schenck, C.H.; Plazzi, G. Sexsomnia: A diagnostic challenge, a case report. Sleep Med. 2018, 43, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobbezoo, F.; Ahlberg, J.; Glaros, A.G.; Kato, T.; Koyano, K.; Lavigne, G.J.; de Leeuw, R.; Manfredini, D.; Svensson, P.; Winocur, E. Bruxism defined and graded: An international consensus. J. Oral Rehabil. 2013, 40, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manfredini, D.; Winocur, E.; Guarda-Nardini, L.; Paesani, D.; Lobbezoo, F. Epidemiology of bruxism in adults: A systematic review of the literature. J. Orofac. Pain 2013, 27, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manfredini, D.; Serra-Negra, J.; Carboncini, F.; Lobbezoo, F. Current Concepts of Bruxism. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2017, 30, 437–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ovcharov, V.K. International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM). Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd9cm.htm (accessed on 3 August 2018).

- Lobbezoo, F.; Ahlberg, J.; Raphael, K.G.; Wetselaar, P.; Glaros, A.G.; Kato, T.; Santiago, V.; Winocur, E.; De Laat, A.; De Leeuw, R.; et al. International consensus on the assessment of bruxism: Report of a work in progress. J. Oral Rehabil. 2018. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiffman, E.; Ohrbach, R.; Truelove, E.; Look, J.; Anderson, G.; Goulet, J.P.; List, T.; Svensson, P.; Gonzalez, Y.; Lobbezoo, F.; et al. Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) for clinical and research applications: Recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group. J. Oral Facial Pain Headache 2014, 28, 6–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, R.B.; Budhiraja, R.; Gottlieb, D.J.; Gozal, D.; Iber, C.; Kapur, V.K.; Marcus, C.L.; Mehra, R.; Parthasarathy, S.; Quan, S.F.; et al. Rules for scoring respiratory events in sleep: Update of the 2007 AASM Manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2012, 8, 597–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study, Year | Sleep Disorders That Co-occurred with Sexsomnia |

|---|---|

| Meira et al., 2016 [14] | Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) |

| Khawaja et al., 2017 [15] | Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) |

| Schenck et al., 2008 [16] | Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) |

| Della Marca et al., 2009 [17] | Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) |

| Ariño et al., 2014 [11] | Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) |

| Gomis et al., 2016 [10] | Sleep-related eating disorder (SRED) |

| Yeh et al., 2016 [19] | Sleepwalking |

| Soca et al., 2016 [20] | Sleepwalking, sleep-related eating disorder, confusional arousals, sleep talking, REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD), obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) |

| Pelin et al., 2012 [21] | Sleepwalking and sleep talking |

| Cicolin et al., 2011 [22] | Sleepwalking, REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD), obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) |

| Shapiro et al., 2003 [23] | Sleepwalking, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) |

| Irfan et al., 2018 [24] | Hypnic jerks, exploding head syndrome, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) |

| Mioč et al., 2018 [25] | Hypnagogic hallucinations, sleep paralysis, night terrors, sleepwalking, sleep-related hyperomotor epilepsy |

| Index | Value |

|---|---|

| Sleep latency | 30.7 min |

| REM latency | 159.5 min |

| AHI | 4.8/h |

| ODI | 5.5/h |

| Average desaturation drop | 2.9% |

| Average SpO2 | 92.5% |

| Minimum SpO2 | 88% |

| Bruxism Episodes Index | 10.1/h |

| Bruxism Burst Index | 12.8/h |

| Index | Value |

|---|---|

| Sleep latency | 10.5 min |

| REM latency | 59.5 min |

| AHI | 33.5/h |

| ODI | 35.7/h |

| Average desaturation drop | 6.1% |

| Average SpO2 | 92.2% |

| Percentage of sleep time with saturation below 90% | 13.4% |

| Bruxism Episodes Index | 11.4/h |

| Bruxism Burst Index | 3.1/h |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martynowicz, H.; Smardz, J.; Wieczorek, T.; Mazur, G.; Poreba, R.; Skomro, R.; Zietek, M.; Wojakowska, A.; Michalek, M.; Wieckiewicz, M. The Co-Occurrence of Sexsomnia, Sleep Bruxism and Other Sleep Disorders. J. Clin. Med. 2018, 7, 233. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm7090233

Martynowicz H, Smardz J, Wieczorek T, Mazur G, Poreba R, Skomro R, Zietek M, Wojakowska A, Michalek M, Wieckiewicz M. The Co-Occurrence of Sexsomnia, Sleep Bruxism and Other Sleep Disorders. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2018; 7(9):233. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm7090233

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartynowicz, Helena, Joanna Smardz, Tomasz Wieczorek, Grzegorz Mazur, Rafal Poreba, Robert Skomro, Marek Zietek, Anna Wojakowska, Monika Michalek, and Mieszko Wieckiewicz. 2018. "The Co-Occurrence of Sexsomnia, Sleep Bruxism and Other Sleep Disorders" Journal of Clinical Medicine 7, no. 9: 233. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm7090233

APA StyleMartynowicz, H., Smardz, J., Wieczorek, T., Mazur, G., Poreba, R., Skomro, R., Zietek, M., Wojakowska, A., Michalek, M., & Wieckiewicz, M. (2018). The Co-Occurrence of Sexsomnia, Sleep Bruxism and Other Sleep Disorders. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 7(9), 233. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm7090233