Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Validation of the Simplified Diabetes Knowledge Test (Arabic Version) for Insulin-Dependent Diabetic Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study in Iraq

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design and Sampling Procedure

2.2. Materials and Measurements

2.3. Instrument Translation

2.4. Validation

2.4.1. Face and Content Validity

2.4.2. Construct Validity

2.4.3. Reliability

2.4.4. Item Difficulty Index

2.4.5. Point Biserial Correlation and Discriminatory Power

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic and Diabetes-Related Information

3.2. Validation

3.2.1. Face Validation

3.2.2. Item Difficulty Index, Point Biserial Correlation, and Discriminatory Power

3.2.3. Content Validation

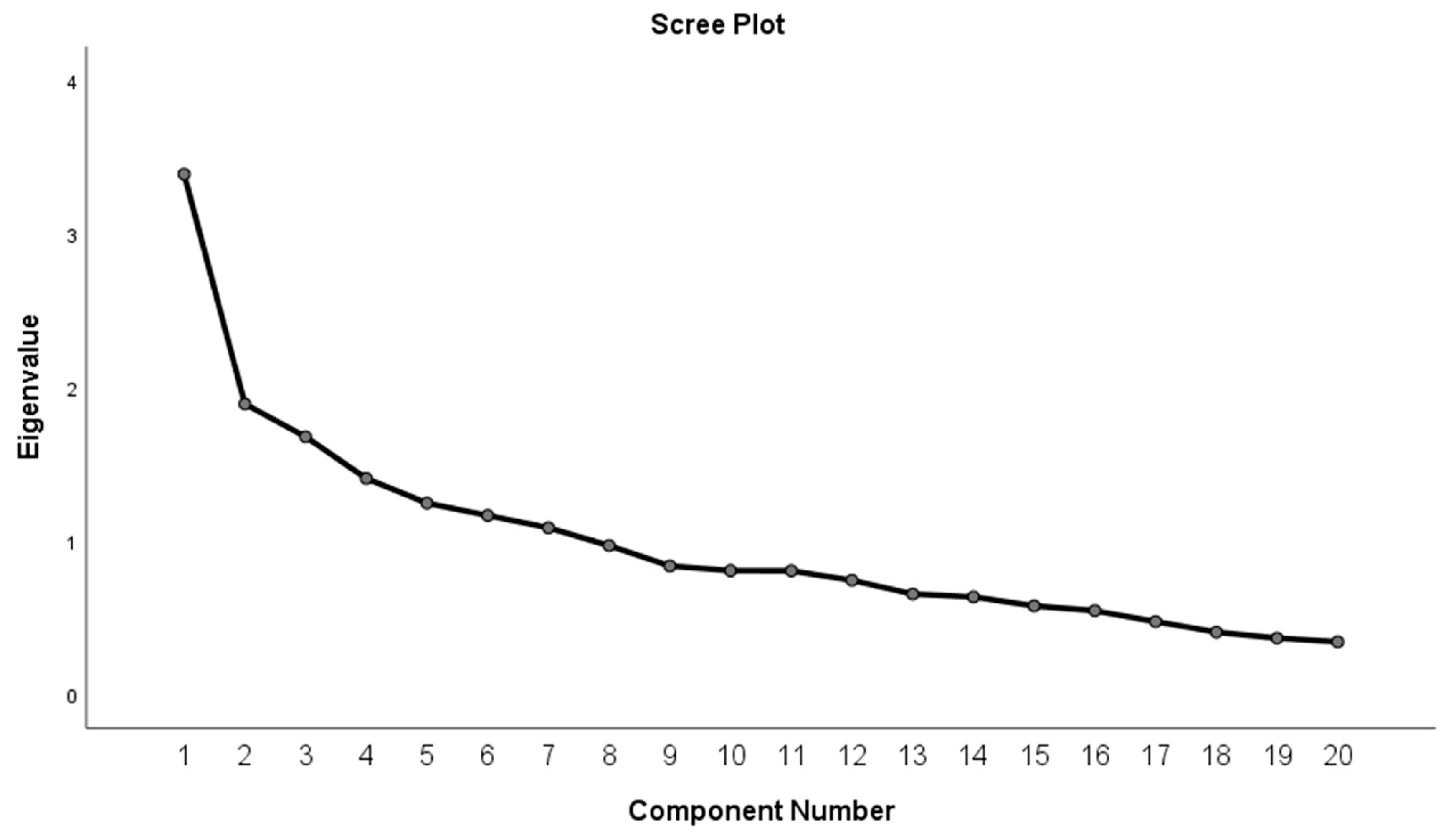

3.2.4. Construct Validation

3.2.5. Reliability

4. Discussion

5. Study Limitation

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| T2D | Type 2 Diabetes |

| T1D | Type 1 Diabetes |

| SDKT-A | Simplified Diabetes Knowledge Test—Arabic version |

| CVR | Content validity ratio |

| CVI | Content validity index |

| DKT | Diabetes Knowledge Test |

References

- Moradkhani, A.; Azami, M.; Mohammadzadeh, P.; Baradaran, H.R.; Saed, L.; Asvad, K.; Kakaei, R.; Khateri, S.; Moradpour, F.; Moradi, Y. The prevalence of all types of diabetes and pre-diabetes in the Eastern Mediterranean countries: A meta-analysis study. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2025, 25, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muche Ewunie, T.; Sisay, D.; Kabthymer, R.H. Diabetes mellitus and its association with central obesity, and overweight/obesity among adults in Ethiopia. A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0269877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, K.L.; Stafford, L.K.; McLaughlin, S.A.; Boyko, E.J.; Vollset, S.E.; Smith, A.E.; Dalton, B.E.; Duprey, J.; Cruz, J.A.; Hagins, H.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of diabetes from 1990 to 2021, with projections of prevalence to 2050: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2023, 402, 203–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.J.; Al-Mamun, M.; Islam, M.R. Diabetes mellitus, the fastest growing global public health concern: Early detection should be focused. Health Sci. Rep. 2024, 7, e2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauwanga, W.N.; Abdalhamed, T.Y.; Ezike, L.A.; Chukwulebe, I.S.; Oo, A.K.; Wilfred, A.; Khan, A.R.A.K.A.; Chukwuwike, J.; Florial, E.; Lawan, H. The pathophysiology and vascular complications of diabetes in chronic kidney disease: A comprehensive review. Cureus 2024, 16, e76498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Saeedi, P.; Karuranga, S.; Pinkepank, M.; Ogurtsova, K.; Duncan, B.; Stein, C.; Basit, A.; Chan, J.; Mbanya, J. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2021, 183, 109119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, N.H.; Rasool, K.H.; Taha, B.M.; Hussein, J.D. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus and type of therapy among Iraqi patients aged 20 years and above in Baghdad. J. Genet. Environ. Conserv. 2022, 10, 78–81. [Google Scholar]

- Abusaib, M.; Ahmed, M.; Nwayyir, H.A.; Alidrisi, H.A.; Al-Abbood, M.; Al-Bayati, A.; Al-Ibrahimi, S.; Al-Kharasani, A.; Al-Rubaye, H.; Mahwi, T.; et al. Iraqi Experts Consensus on the Management of Type 2 Diabetes/Prediabetes in Adults. Clin. Med. Insights Endocrinol. Diabetes 2020, 13, 1179551420942232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kebbi, I.M.; Bidikian, N.H.; Hneiny, L.; Nasrallah, M.P. Epidemiology of type 2 diabetes in the Middle East and North Africa: Challenges and call for action. World J. Diabetes 2021, 12, 1401–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Janabi, T. Barriers to the Utilization of Primary Health Centers (PHCs) in Iraq. Epidemiologia 2023, 4, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansbro, É.; Schmid, B.; Willis, R.; M-Amen, K.; Mahmood, K.; Abdulkareem, I.; Frederiksen, S.; Roswall, J.; Perone, S.A.; Roberts, B.; et al. Decentralising healthcare for diabetes and hypertension from secondary to primary level in a humanitarian setting in Kurdistan, Iraq: A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2025, 25, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugshan, W.; Qahtani, S.; Alwagdani, N.; Alharthi, M.; Alqarni, A.; Alsuat, H.; Almotairi, A. Role of health awareness campaigns in improving public health: A systematic review. Int. J. Life Sci. Pharma. Res. 2022, 12, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Joshi, S.H. Self-Care Practices and Their Role in the Control of Diabetes: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e41409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ernawati, U.; Wihastuti, T.A.; Utami, Y.W. Effectiveness of Diabetes Self-Management Education (Dsme) in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2Dm) Patients: Systematic Literature Review. J. Public Health Res. 2021, 10, 2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sękowski, K.; Grudziąż-Sękowska, J.; Pinkas, J.; Jankowski, M. Public knowledge and awareness of diabetes mellitus, its risk factors, complications, and prevention methods among adults in Poland—A 2022 nationwide cross-sectional survey. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1029358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amr, R.A.; Al-Smadi, A.M.; Akasheh, R.T. Diabetes knowledge and behaviour: A cross-sectional study of Jordanian adults. Diabetologia 2025, 68, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cangelosi, G.; Mancin, S.; Pantanetti, P.; Nguyen, C.T.T.; Morales Palomares, S.; Biondini, F.; Sguanci, M.; Petrelli, F. Lifestyle Medicine Case Manager Nurses for Type Two Diabetes Patients: An Overview of a Job Description Framework—A Narrative Review. Diabetology 2024, 5, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, A.; Bhatta, D.N.; Aryal, U.R. Diabetes related health knowledge, attitude and practice among diabetic patients in Nepal. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2015, 15, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassahun, T.; Gesesew, H.; Mwanri, L.; Eshetie, T. Diabetes related knowledge, self-care behaviours and adherence to medications among diabetic patients in Southwest Ethiopia: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2016, 16, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colberg, S.R.; Sigal, R.J.; Yardley, J.E.; Riddell, M.C.; Dunstan, D.W.; Dempsey, P.C.; Horton, E.S.; Castorino, K.; Tate, D.F. Physical Activity/Exercise and Diabetes: A Position Statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2016, 39, 2065–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, T.W.; Tareke, M.; Tirfie, M. Self-care practices and associated factors among diabetes patients attending the outpatient department in Bahir Dar, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Res. Notes 2018, 11, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhaik, S.; Anshasi, H.A.; Alkhawaldeh, J.f.; Soh, K.L.; Naji, A.M. An assessment of self-care knowledge among patients with diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2019, 13, 390–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherji, A.B.; Lu, D.; Qin, F.; Hedlin, H.; Johannsen, N.M.; Chung, S.; Kobayashi, Y.; Haddad, F.; Lamendola, C.; Basina, M.; et al. Effectiveness of a Community-Based Structured Physical Activity Program for Adults with Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2247858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karaoui, L.R.; Deeb, M.E.; Nasser, L.; Hallit, S. Knowledge and practice of patients with diabetes mellitus in Lebanon: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzgerald, J.T.; Funnell, M.M.; Anderson, R.M.; Nwankwo, R.; Stansfield, R.B.; Piatt, G.A. Validation of the revised brief Diabetes Knowledge Test (DKT2). Diabetes Educ. 2016, 42, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aris, M.A.M.; Pasi, H.; Shalihin, M.S.E.; Othman, U.; Rahim, N.-H.A. Translation and Validation of Malay Version of the Simplified Diabetes Knowledge Test (DKT). Malays. J. Med. Health Sci. 2022, 18, 76–84. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, G.S.; Mughal, S.; Barnett, A.H.; Fitzgerald, J.; Lloyd, C.E. Modification and validation of the Revised Diabetes Knowledge Scale. Diabet. Med. 2011, 28, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, Z.D.; Kamal, H.N.; Salim, L.R.; Grain, H.M.J.S.; Alqiraishi, Z.H.A.; Algaragolle, W.M.H.; Dawood, I.I. The Gender Discrimination and Regional Difference Effect on Reading Literacy of College Students: A Case from Iraq. Eurasian J. Appl. Linguist. 2022, 8, 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.; Gøtzsche, P.; Vandenbroucke, J. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Rev. Esp. Salud Publica 2019, 82, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streiner, D.L.; Norman, G.R.; Cairney, J. Health Measurement Scales: A Practical Guide to Their Development and Use; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulameer, S.A.; Syed Sulaiman, S.A.; Hassali, M.A.; Sahib, M.N.; Subramaniam, K. Psychometric properties of the Malay version of the Osteoporosis Health Belief Scale (OHBS-M) among Type 2 diabetic patients. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2014, 17, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulameer, S.A.; Syed Sulaiman, S.A.; Hassali, M.A.; Subramaniam, K.; Sahib, M.N. Psychometric Properties of Osteoporosis Knowledge Tool and Self-Management Behaviours Among Malaysian Type 2 Diabetic Patients. J. Community Health 2013, 38, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000; ISBN 9241208945. [Google Scholar]

- ElSayed, N.A.; Aleppo, G.; Aroda, V.R.; Bannuru, R.R.; Brown, F.M.; Bruemmer, D.; Collins, B.S.; Hilliard, M.E.; Isaacs, D.; Johnson, E.L.; et al. 6. Glycemic Targets: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2023. Diabetes Care 2022, 46, S97–S110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaee, M.; Kamrani, F.; Imannezhad, M.; Shahri, H.H.; Saihood, W.K.; Rezvani, A.; Far, P.M.; Mahaki, H.; Esmaily, H.; Moohebati, M.; et al. Beyond traditional metrics: Evaluating the triglyceride-total cholesterol-body weight index (TCBI) in cardiovascular risk assessment. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2025, 25, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AkbariRad, M.; Darroudi, S.; Farsi, F.; Mohajer, N.; Ghalibaf, A.M.; Firoozi, A.; Esmaeili, H.; Izadi, H.S.; Ghayour-Mobarhan, M.; Moohebati, M. Investigation of the relationship between atherogenic index, anthropometric characteristics, and 10-year risk of metabolic syndrome: A population-based study. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2024, 193, 2705–2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudo, M.; Shamekhi, J.; Aksoy, A.; Al-Kassou, B.; Tanaka, T.; Silaschi, M.; Weber, M.; Nickenig, G.; Zimmer, S. A simply calculated nutritional index provides clinical implications in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2024, 113, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wild, D.; Grove, A.; Martin, M.; Eremenco, S.; McElroy, S.; Verjee-Lorenz, A.; Erikson, P. Principles of good practice for the translation and cultural adaptation process for patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measures: Report of the ISPOR task force for translation and cultural adaptation. Value Health 2005, 8, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulameer, S.A.; Al-Jewari, W.M.; Sahib, M.N. Psychological health status and salivary IgA among pharmacy students in Iraq: Validation of PSS-4 and WHO-5 well-being (Arabic version). Pharm. Educ. 2019, 19, 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulameer, S.A.; Syed Sulaiman, S.A.; Hassali, M.A.; Subramaniam, K.; Sahib, M.N. Psychometric properties and osteoprotective behaviors among type 2 diabetic patients: Osteoporosis self-efficacy scale Malay version (OSES-M). Osteoporos. Int. 2013, 24, 929–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, A.L.; Julious, S.A.; Cooper, C.L.; Campbell, M.J. Estimating the sample size for a pilot randomised trial to minimise the overall trial sample size for the external pilot and main trial for a continuous outcome variable. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2016, 25, 1057–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawshe, C.H. A quantitative approach to content validity. Pers. Psychol. 1975, 28, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics; Sage Publications Limited: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasiah, S.-M.S.; Isaiah, R. Relationship between item difficulty and discrimination indices in true/false-type multiple choice questions of a para-clinical multidisciplinary paper. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 2006, 35, 67–71. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, G.A. On the theory of test discrimination. Psychometrika 1949, 14, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kähm, K.; Laxy, M.; Schneider, U.; Holle, R. Exploring Different Strategies of Assessing the Economic Impact of Multiple Diabetes-Associated Complications and Their Interactions: A Large Claims-Based Study in Germany. Pharmacoeconomics 2019, 37, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulameer, S.A.; Syed Sulaiman, S.A.; Hassali, M.A.A.; Subramaniam, K.; Sahib, M.N. Is there a link between osteoporosis and type 1 diabetes? Findings from a systematic review of the literature. Diabetol. Int. 2012, 3, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulameer, S.A.; Sahib, M.N.; Sulaiman, S.A.S. The Prevalence of Osteopenia and Osteoporosis Among Malaysian Type 2 Diabetic Patients Using Quantitative Ultrasound Densitometer. Open Rheumatol. J. 2018, 12, 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safita, N.; Islam, S.M.S.; Chow, C.K.; Niessen, L.; Lechner, A.; Holle, R.; Laxy, M. The impact of type 2 diabetes on health related quality of life in Bangladesh: Results from a matched study comparing treated cases with non-diabetic controls. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2016, 14, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fottrell, E.; Ahmed, N.; Shaha, S.K.; Jennings, H.; Kuddus, A.; Morrison, J.; Akter, K.; Nahar, B.; Nahar, T.; Haghparast-Bidgoli, H. Diabetes knowledge and care practices among adults in rural Bangladesh: A cross-sectional survey. BMJ Glob. Health 2018, 3, e000891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Aboudi, I.S.; Hassali, M.A.; Shafie, A.A. Knowledge, attitudes, and quality of life of type 2 diabetes patients in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. J. Pharm. Bioall. Sci. 2016, 8, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Zahrani, A.M.; Al Shaikh, A. Glycemic Control in Children and Youth with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus in Saudi Arabia. Clin. Med. Insights Endocrinol. Diabetes 2019, 12, 1179551418825159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahib, M.N. Psychometric properties and assessment of the Osteoporosis health Belief scale among the general Arabic population. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2018, 12, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, S.; Alzubaidi, H.; Samorinha, C.; Al Radhaideh, A. Validation and Psychometric Evaluation of Diabetes Literacy, Numeracy, and Knowledge Tools in the Arabic Context. Sci. Diabetes Self Manag. Care 2023, 49, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, S.; Mahameed, S.; AlHariri, Y. Translation and culture adaptation of the simplified diabetes knowledge test, the literacy assessment for diabetes and the diabetes numeracy test. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2020, 16, 1050–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haoues, M.; Zedini, C.; Chadli-Chaieb, M. Arabic version of the simplified diabetes knowledge scale: Psychometric and linguistic validation. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2022, 41, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asim, A.; Azaam, A.; Ziad, A. Validity and Reliability of the Arabic Translation of Diabetes Knowledge Test (DKT1). Malays. J. Med. Health Sci. 2022, 18, 61–67. [Google Scholar]

- Sahib, M.N. Validation and Assessment of Osteoporosis Self-Efficacy Among Iraqi General Population. Open Nurs. J. 2018, 12, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jasper, U.S.; Ogundunmade, B.G.; Opara, M.C.; Akinrolie, O.; Pyiki, E.B.; Umar, A. Determinants of diabetes knowledge in a cohort of Nigerian diabetics. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2014, 13, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Itumalla, R.; Perera, B.; Tharwat Elabbasy, M.; Singh, M. Patient knowledge about diabetes: Illness symptoms, complications and preventive personal lifestyle factors. Health Psychol. Res. 2022, 10, 37520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, M.J.; Mustafa, H.; Ali, H. Knowledge of diabetes among patients in the United Arab Emirates and trends since 2001: A study using the Michigan Diabetes Knowledge Test. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2016, 22, 742–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Adsani, A.; Moussa, M.; Al-Jasem, L.; Abdella, N.; Al-Hamad, N. The level and determinants of diabetes knowledge in Kuwaiti adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 2009, 35, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill-Briggs, F.; Adler, N.E.; Berkowitz, S.A.; Chin, M.H.; Gary-Webb, T.L.; Navas-Acien, A.; Thornton, P.L.; Haire-Joshu, D. Social Determinants of Health and Diabetes: A Scientific Review. Diabetes Care 2020, 44, 258–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Wagdi, B.E.; Al-Hanawi, M.K. Knowledge, attitude and practice toward diabetes among the public in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1326675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolde, W.; Demeke, A.D.; Atle, D.; Girma, D.; Hailu, S. Knowledge, attitude, and practice towards diabetes mellitus among Chiro town population, Eastern Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulameer, S.A. A cross-sectional pilot study to investigate diabetic knowledge and pharmaceutical care practice among registered and unregistered pharmacists in Iraq. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 8, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Abdulameer, S.A. Knowledge and pharmaceutical care practice regarding inhaled therapy among registered and unregistered pharmacists: An urgent need for a patient-oriented health care educational program in Iraq. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2018, 13, 879–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordin, N.; Mohd Hairon, S.; Yaacob, N.M.; Abdul Hamid, A.; Hassan, N. Effects of FamilyDoctor Concept and Doctor-Patient Interaction Satisfaction on Glycaemic Control among Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients in the Northeast Region of Peninsular Malaysia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjbar, F.; Karimi, M.; Zare, E.; Ghahremani, L. The effect of educational intervention based on the behavioral reasoning theory on self-management behaviors in type 2 diabetes patients: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinsa, F.; Aga, F.; Gela, D. Factors associated with knowledge of diabetic retinopathy among adults with diabetes on follow-up care at public hospitals in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: An institution-based cross-sectional study. Front. Clin. Diabetes Healthc. 2025, 6, 1527143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zowgar, A.M.; Siddiqui, M.I.; Alattas, K.M. Level of diabetes knowledge among adult patients with diabetes using diabetes knowledge test. Saudi Med. J. 2018, 39, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrashed, F.A.; Iqbal, M.; Al-Regaiey, K.A.; Ansari, A.A.; Alderaa, A.A.; Alhammad, S.A.; Alsubiheen, A.M.; Ahmad, T. Evaluating diabetic foot care knowledge and practices at education level. Medicine 2024, 103, e39449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossman, E.L. Physical Activity in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Updated Consensus Statement From the ACSM. Am. Fam. Physician 2023, 107, 103–104. [Google Scholar]

- Goldfarb, I.; Giladi, A.; Barak, S.; Lev, I.; Dor-Haim, H. Physical activity as clinical practice care for patients with type 2 diabetics and its implementation in routine clinical care: An expert opinion survey. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1518285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kivimäki, M.; Kuosma, E.; Ferrie, J.E.; Luukkonen, R.; Nyberg, S.T.; Alfredsson, L.; Batty, G.D.; Brunner, E.J.; Fransson, E.; Goldberg, M.; et al. Overweight, obesity, and risk of cardiometabolic multimorbidity: Pooled analysis of individual-level data for 120813 adults from 16 cohort studies from the USA and Europe. Lancet Public Health 2017, 2, e277–e285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, H.S.; Mohammed, M.S. Atherogenic Indices in Type 2 Diabetic Iraqi Patients and Its Association with Cardiovascular Disease Risk. J. Fac. Med. Baghdad 2023, 65, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.N.; Ali, R.J. Atherogenic index of plasma as a biomarker of atherogenecity in type 2 diabetes mellitus in Erbil city. Zanco J. Med. Sci. 2023, 27, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajwal, S.K.; Saud, A.T.; Jihad, S.K.; Ayad, Z.M.; Obaid, F.T.; Hermis, A.H.; Al-Mamoori, H.M.K.; Al-Tmimi, N.M.A. Association between Self Care and Knowledge of Type II of Diabetic Patients Attending Al-Hilla City, Iraq. Med. J. Babylon 2025, 22, 372–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepeda Marte, J.L.; Ruiz-Matuk, C.; Mota, M.; Pérez, S.; Recio, N.; Hernández, D.; Fernández, J.; Porto, J.; Ramos, A. Quality of life and metabolic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus diagnosed individuals. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2019, 13, 2827–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafar, N.; Huriyati, E.; Haryani, N.; Setyawati, A. Enhancing knowledge of Diabetes self-management and quality of life in people with Diabetes Mellitus by using Guru Diabetes Apps-based health coaching. J. Public Health Res. 2023, 12, 22799036231186338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Total Sample Knowledge (N = 210) Mean ± SD (Median) | Low Knowledge (N = 151) Frequency (%) | High Knowledge (N = 59) Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| <45 | 11.96 ± 2.88 (12) * | 67 (44.37) | 31 (52.54) |

| 45–54 | 10.15 ± 3.93 (10) | 30 (19.86) | 10 (16.94) |

| 55–64 | 10.51 ± 3.44 (10) | 32 (21.19) | 11 (18.64) |

| ≥65 | 10.31 ± 3.64 (10) | 22 (14.56) | 7 (11.86) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 11.07 ± 3.26 (12) | 71 (47.01) | 24 (40.67) |

| Female | 11.10 ± 3.53 (11) | 80 (52.98) | 35 (59.32) |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married | 10.86 ± 3.56 (11) | 123 (81.45) | 48 (81.35) |

| Single | 12.10 ± 2.36 (12) | 28 (18.54) | 11 (18.64) |

| Education level | |||

| No formal education | 9.31 ± 3.31 (9.50) * | 47 (31.12) | 7 (11.86) |

| Secondary | 11.16 ± 3.39 (12) | 50 (33.11) | 20 (33.89) |

| University | 12.15 ± 3.02 (13) | 54 (35.76) | 32 (54.23) |

| Employment status | |||

| Not employed | 10.74 ± 3.43 (11) | 88 (58.27) | 33 (55.93) |

| Employed | 11.57 ± 3.32 (12) | 63 (41.72) | 26 (44.06) |

| Monthly income | |||

| No payment | 12.02 ± 2.88 (13) | 32 (21.19) | 17 (28.81) |

| 100,000–599,000 IQD | 9.91 ± 3.55 (10) * | 63 (41.72) | 13 (22.03) |

| 600,000–1,000,000 IQD | 11.61 ± 3.28 (12) | 56 (37.08) | 29 (49.15) |

| Smoking habit | |||

| Not smoking | 11.45 ± 3.19 (12) * | 123 (81.45) | 53 (89.83) |

| Smoking | 9.24 ± 3.90 (9) | 28 (18.54) | 6 (10.16) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | |||

| Normal (18.5–22.9) | 10.97 ± 3.31 (12) | 51 (33.77) | 15 (25.42) |

| Overweight (23–27.4) | 11.11 ± 3.53 (11) | 57 (37.74) | 24 (40.67) |

| Obese (≥27.5) | 11.19 ± 3.34 (12) | 43 (28.47) | 20 (33.89) |

| Family Historyof diabetes | |||

| Yes | 11.23 ± 3.46 (12) | 77 (50.99) | 34 (57.62) |

| No | 10.94 ± 3.35 (11) | 74 (49.00) | 25 (42.37) |

| Living area | |||

| Al-Kharkh | 11.26 ± 3.33 (12) | 82 (54.30) | 35 (59.32) |

| Al-Rusafa | 10.87 ± 3.50 (11) | 69 (45.69) | 24 (40.67) |

| Variable | Total Sample Knowledge (N = 210) Mean ± SD (Median) | Low Knowledge (N = 151) Frequency (%) | High Knowledge (N = 59) Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glycemic (HbA1c) control | |||

| Good control | 12.28 ± 2.80 (13) | 18 (11.9) | 11 (18.60) |

| Inadequate control | 12.51 ± 2.73 (13) | 21 (13.90) | 14 (23.72) |

| Poor control | 10.51 ± 3.51 (11) | 112 (74.20) | 34 (57.60) |

| Diabetes Duration (years) | |||

| <5 | 11.52 ± 3.60 (12) | 16 (10.59) | 9 (15.25) |

| 5–9 | 10.69 ± 3.38 (11) | 57 (37.74) | 13 (22.03) |

| 10–14 | 11.00 ± 3.29 (11) | 39 (25.82) | 16 (27.11) |

| 15–19 | 10.61 ± 3.45 (11) | 19 (12.58) | 9 (15.25) |

| ≥20 | 12.22 ± 3.36 (13) | 20 (13.24) | 12 (20.33) |

| Hospitalization (last year) | |||

| Yes | 10.69 ± 3.49 (11) | 54 (35.76) | 20 (33.89) |

| No | 11.31 ± 3.34 (12) | 97 (64.23) | 39 (66.10) |

| Type of insulin diabetes user | |||

| T1D | 11.32 ± 3.21 (12) | 109 (72.18) | 45 (76.27) |

| T2D | 10.46 ± 3.83 (11) | 42 (27.81) | 14 (23.72) |

| Number of Co-morbidities | |||

| No Co-morbidities | 11.66 ± 3.16 (12) | 49 (32.45) | 22 (37.28) |

| 1 Co-morbidities | 10.66 ± 3.83 (11) | 43 (28.47) | 13 (22.03) |

| 2 Co-morbidities | 10.76 ± 3.47 (10.5) | 28 (18.54) | 10 (16.94) |

| 3 Co-morbidities | 11.21 ± 2.81 (10.5) | 10 (6.62) | 4 (6.77) |

| 4 or more Co-morbidities | 10.90 ± 3.28 (11) | 21 (13.91) | 10 (16.94) |

| Do you get diabetes education last year | |||

| Yes | 11.51 ± 3.32 (12) | 78 (51.65) | 36 (61.01) |

| No | 10.59 ± 3.45 (11) | 73 (48.34) | 23 (38.98) |

| Visit physician at private clinic last year | |||

| Yes | 11.18 ± 3.31 (12) | 114 (75.49) | 46 (77.96) |

| No | 10.82 ± 3.70 (11) | 37 (24.50) | 13 (22.03) |

| Number of reflo-checks at home (last week) | |||

| No | 10.82 ± 2.81 (10) | 17 (11.25) | 5 (8.47) |

| once | 10.32 ± 3.45 (10) | 38 (25.16) | 9 (15.25) |

| twice | 11.17 ± 3.62 (12) | 25 (16.55) | 5 (8.47) |

| Three times | 8.65 ± 3.12 (9) | 16 (10.59) | 1 (1.69) |

| Four times | 10.20 ± 4.09 (11) | 11 (7.28) | 4 (6.77) |

| Five or more | 12.29 ± 2.95 (13) * | 44 (29.13) | 35 (59.32) |

| If you do not have glucose meter at home, you prefer to check blood glucose at: | |||

| Private clinic (reflo-check) | 12.27 ± 3.62 (14) *,** | 7 (4.63) | 8 (13.55) |

| Pharmacy (reflo-check) | 9.90 ± 3.51 (9) | 39 (25.82) | 10 (16.94) |

| Laboratory | 11.89 ± 2.88 (12) *,** | 74 (49.00) | 34 (57.62) |

| Nurse (reflo-check) | 9.89 ± 3.83 (11) | 31 (20.52) | 7 (11.86) |

| TC | |||

| Good < 200 mg/dL | 11.33 ± 3.28 (12) | 109 (72.18) | 44 (74.57) |

| Poor ≥ 200 mg/dL | 10.46 ± 3.67 (11) | 42 (27.81) | 15 (25.42) |

| HDL-C | |||

| Good ≥ 40 mg/dL | 10.59 ± 3.51 (11) | 63 (41.72) | 18 (30.50) |

| Poor < 40 mg/dL | 11.40 ± 3.30 (12) | 88 (58.27) | 41 (69.49) |

| LDL-C | |||

| Good < 100 mg/dL | 11.20 ± 3.22 (12) | 86 (56.95) | 33 (55.93) |

| Poor ≥ 130 mg/dL | 10.95 ± 3.64 (12) | 65 (43.04) | 26 (44.06) |

| TG | |||

| Good < 150 mg/dL | 12.01 ± 2.84 (12) * | 55 (36.42) | 26 (44.06) |

| Poor ≥ 150 mg/dL | 10.51 ± 3.60 (11) | 96 (63.57) | 33 (55.93) |

| CRI-I | |||

| <3.5 | 11.90 ± 3.09 (13) * | 51 (33.80) | 30 (50.80) |

| ≥3.5 | 10.58 ± 3.49 (11) | 100 (66.20) | 29 (49.20) |

| CRI-II | |||

| <3.3 | 11.42 ± 3.16 (12) | 115 (76.20) | 47 (79.70) |

| ≥3.3 | 9.98 ± 3.94 (10) | 36 (23.80) | 12 (20.30) |

| Triglyceride/HDL ratio | |||

| 3.0 | 12.47 ± 3.00 (13) * | 23 (53.50) | 20 (46.50) |

| ≥3.0 | 10.74 ± 3.42 (11) | 128 (76.60) | 39 (23.40) |

| non-HDL-c | |||

| <130 mg/dL | 11.48 ± 3.24 (12) | 72 (67.30) | 35 (32.70) |

| ≥130 mg/dL | 10.69 ± 3.53 (11) | 79 (76.70) | 24 (23.30) |

| AC | |||

| <3.0 | 11.90 ± 3.09 (13) * | 51 (63.0) | 30 (37.0) |

| ≥3.0 | 10.58 ± 3.49 (11) | 100 (77.50) | 29 (22.50) |

| TCBI | |||

| <985.3 | 13.11 ± 2.27 (13) * | 10 (55.60) | 8 (44.40) |

| ≥985.3 | 10.90 ± 3.43 (11) | 141 (73.40) | 51 (26.60) |

| Question Number | Correct Response (%) | Difficulty Index | Point Biserial Correlation † | Cronbach’s Alpha If Item Deleted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question Number 1 | 81.10 | 0.763 | 0.132 | 0.661 |

| Question Number 2 | 46.70 | 0.360 | 0.139 | 0.662 |

| Question Number 3 | 71.90 | 0.719 | 0.204 | 0.654 |

| Question Number 4 | 67.60 | 0.728 | 0.411 | 0.631 |

| Question Number 5 | 46.70 | 0.465 | 0.109 | 0.666 |

| Question Number 6 | 31.90 | 0.360 | 0.093 | 0.666 |

| Question Number 7 | 49.50 | 0.544 | 0.306 | 0.642 |

| Question Number 8 | 74.30 | 0.789 | 0.199 | 0.655 |

| Question Number 9 | 78.10 | 0.851 | 0.115 | 0.663 |

| Question Number 10 | 36.70 | 0.395 | 0.370 | 0.635 |

| Question Number 11 | 47.10 | 0.474 | 0.446 | 0.625 |

| Question Number 12 | 34.80 | 0.351 | 0.029 | 0.674 |

| Question Number 13 | 77.60 | 0.877 | 0.406 | 0.633 |

| Question Number 14 | 48.10 | 0.482 | 0.355 | 0.636 |

| Question Number 15 | 25.20 | 0.237 | 0.028 | 0.672 |

| Question Number 16 | 40.00 | 0.404 | 0.296 | 0.644 |

| Question Number 17 | 57.60 | 0.544 | 0.470 | 0.622 |

| Question Number 18 | 74.80 | 0.754 | 0.535 | 0.618 |

| Question Number 19 | 82.40 | 0.851 | 0.127 | 0.661 |

| Question Number 20 | 37.10 | 0.509 | 0.077 | 0.669 |

| No. of Question (Item) | ne | N | N/2 | CVR | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question Number 1 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 1 | Met the criteria for retention |

| Question Number 2 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 1 | Met the criteria for retention |

| Question Number 3 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 1 | Met the criteria for retention |

| Question Number 4 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 1 | Met the criteria for retention |

| Question Number 5 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 1 | Met the criteria for retention |

| Question Number 6 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 1 | Met the criteria for retention |

| Question Number 7 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 1 | Met the criteria for retention |

| Question Number 8 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 1 | Met the criteria for retention |

| Question Number 9 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 1 | Met the criteria for retention |

| Question Number 10 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 1 | Met the criteria for retention |

| Question Number 11 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 1 | Met the criteria for retention |

| Question Number 12 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 1 | Met the criteria for retention |

| Question Number 13 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 1 | Met the criteria for retention |

| Question Number 14 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 1 | Met the criteria for retention |

| Question Number 15 | 9 | 10 | 5 | 0.8 | Met the criteria for retention |

| Question Number 16 | 9 | 10 | 5 | 0.8 | Met the criteria for retention |

| Question Number 17 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 1 | Met the criteria for retention |

| Question Number 18 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 1 | Met the criteria for retention |

| Question Number 19 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 1 | Met the criteria for retention |

| Question Number 20 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 1 | Met the criteria for retention |

| No. of Question (Item) | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | Communalities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question Number 1 | 0.422 | 0.258 | |||

| Question Number 2 | 0.600 | 0.347 | |||

| Question Number 3 | 0.588 | 0.375 | |||

| Question Number 4 | 0.520 | 0.452 | |||

| Question Number 5 | 0.579 | 0.528 | |||

| Question Number 6 | 0.295 | 0.265 | |||

| Question Number 7 | 0.477 | 0.228 | |||

| Question Number 8 | 0.605 | 0.504 | |||

| Question Number 9 | 0.720 | 0.515 | |||

| Question Number 10 | 0.614 | 0.382 | |||

| Question Number 11 | 0.723 | 0.499 | |||

| Question Number 12 | 0.735 | 0.577 | |||

| Question Number 13 | 0.664 | 0.452 | |||

| Question Number 14 | 0.547 | 0.342 | |||

| Question Number 15 | 0.111 | 0.205 | |||

| Question Number 16 | 0.599 | 0.405 | |||

| Question Number 17 | 0.492 | 0.574 | |||

| Question Number 18 | 0.602 | 0.524 | |||

| Question Number 19 | 0.493 | 0.319 | |||

| Question Number 20 | 0.786 | 0.614 | |||

| Eigenvalues | 3.390 | 1.892 | 1.678 | 1.406 | |

| % of variance | 16.950 | 9.459 | 8.390 | 7.029 | Total = 41.83% |

| Reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) | α = 0.703 | α = 0.504 | α = 0.518 | α = 0.485 | Total scale: α= 0.662 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Abdulameer, S.A.; Sahib, M.N. Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Validation of the Simplified Diabetes Knowledge Test (Arabic Version) for Insulin-Dependent Diabetic Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study in Iraq. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 1164. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031164

Abdulameer SA, Sahib MN. Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Validation of the Simplified Diabetes Knowledge Test (Arabic Version) for Insulin-Dependent Diabetic Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study in Iraq. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(3):1164. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031164

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbdulameer, Shaymaa Abdalwahed, and Mohanad Naji Sahib. 2026. "Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Validation of the Simplified Diabetes Knowledge Test (Arabic Version) for Insulin-Dependent Diabetic Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study in Iraq" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 3: 1164. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031164

APA StyleAbdulameer, S. A., & Sahib, M. N. (2026). Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Validation of the Simplified Diabetes Knowledge Test (Arabic Version) for Insulin-Dependent Diabetic Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study in Iraq. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(3), 1164. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031164