Pediatric Head & Neck Free-Flap Reconstruction Outcomes: Score-Based Effectiveness Assessment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- 26 patients underwent tumor resection with simultaneous reconstruction.

- 20 patients underwent reconstruction only (18 due to craniofacial malformations, 1 due to chemical burn of the oral cavity, and 1 due to traumatic maxillary defect).

- 8 children required an additional flap procedure (2 for a subsequent tumor in a different location, 6 due to necrosis of the primary flap).

2.1. Outcome Measures

2.1.1. Treatment Effectiveness Score

- 100 points indicated proper integration of the flap at the recipient site and complete healing of the donor site.

- 0 points indicated total flap loss due to necrosis.

2.1.2. Healing Assessment

2.1.3. Functional Assessment

2.2. Age as a Variable

2.3. Postoperative Flap Monitoring

2.4. Data Collection and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

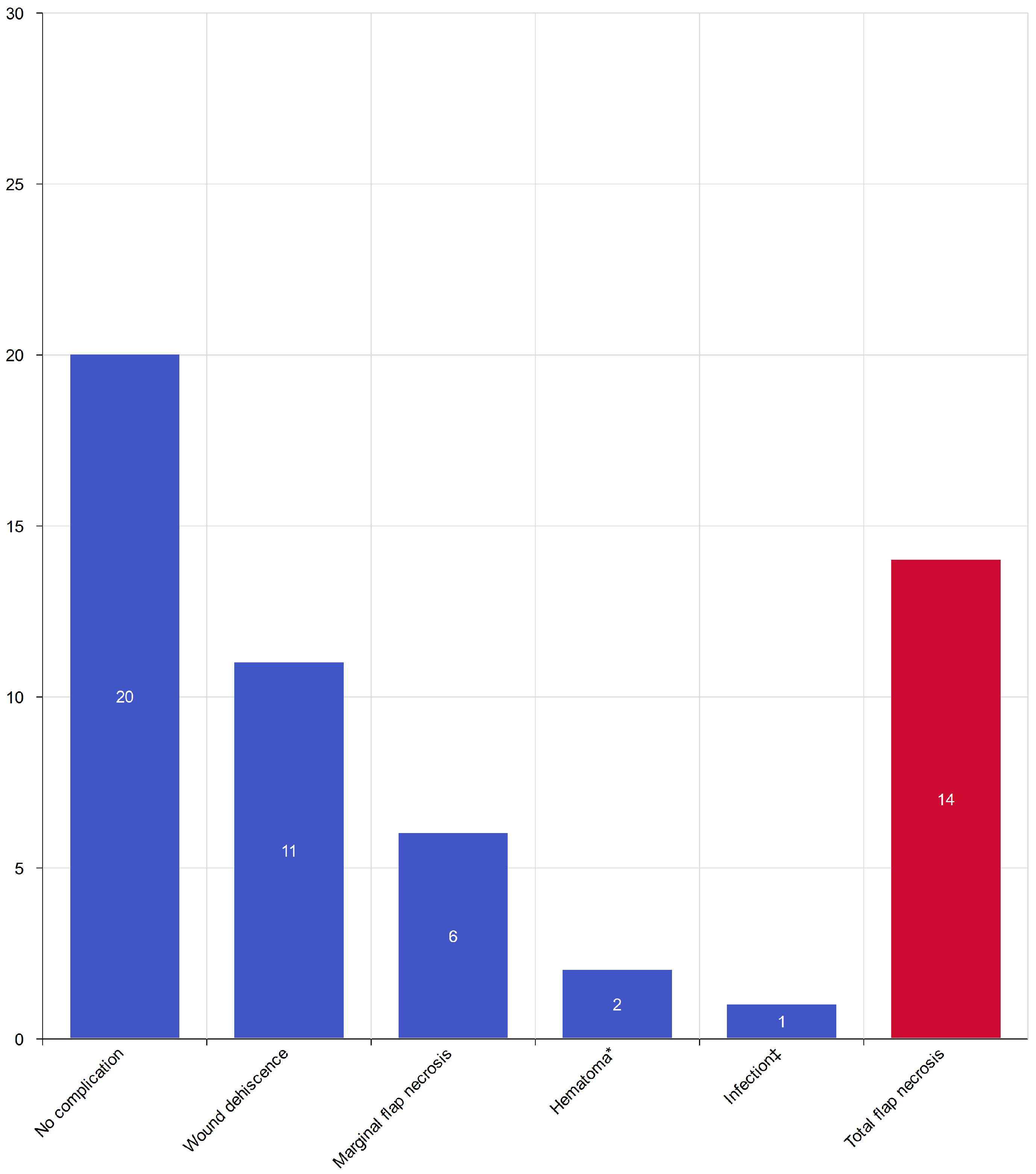

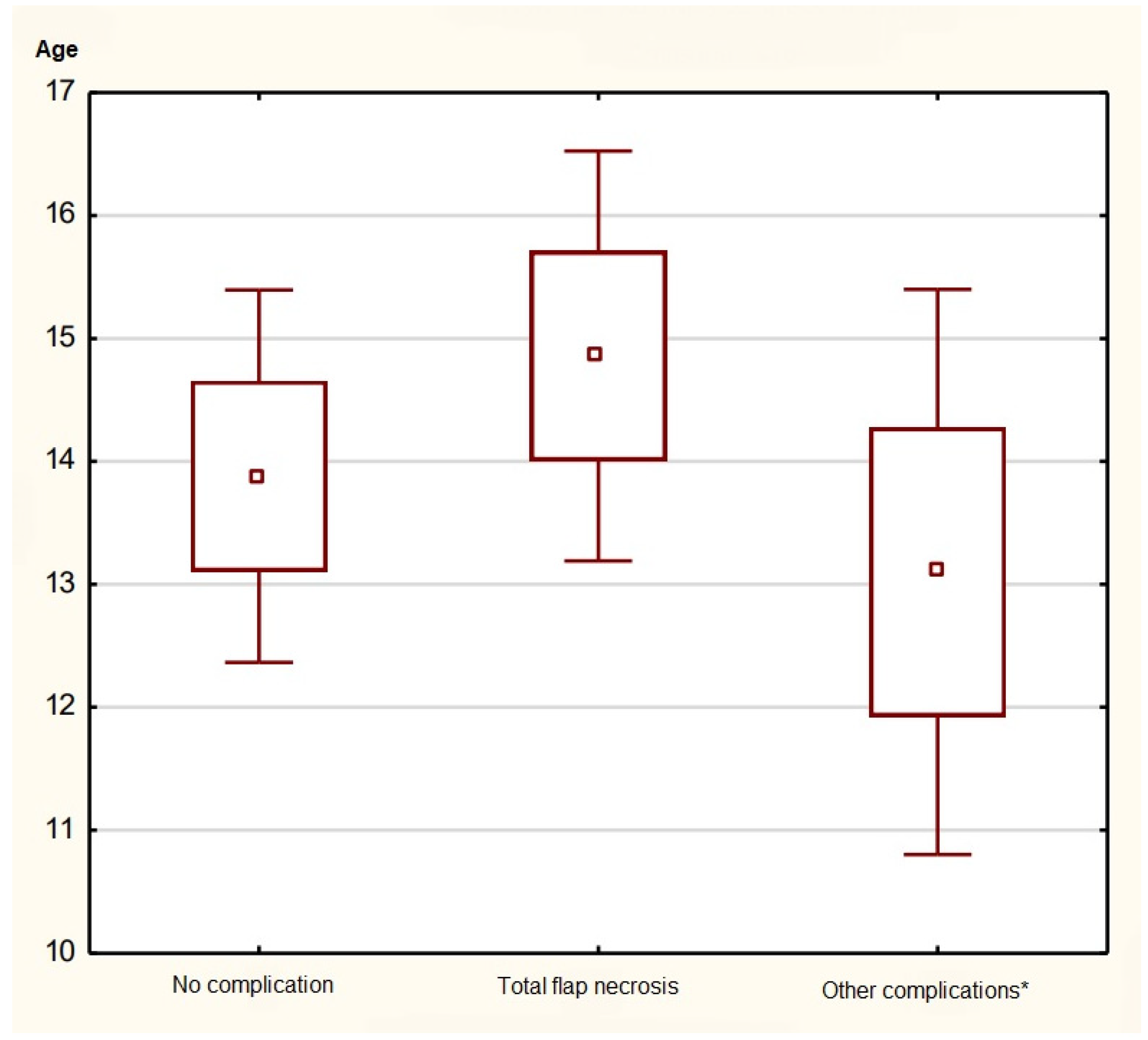

3.1. Overall Treatment Effectiveness

- marginal necrosis—6 cases (11.1%),

- wound dehiscence—11 cases (20.3%),

- hematoma formation within 3 postoperative days—2 cases (3.7%),

- infection within 30 days—1 case (1.8%).

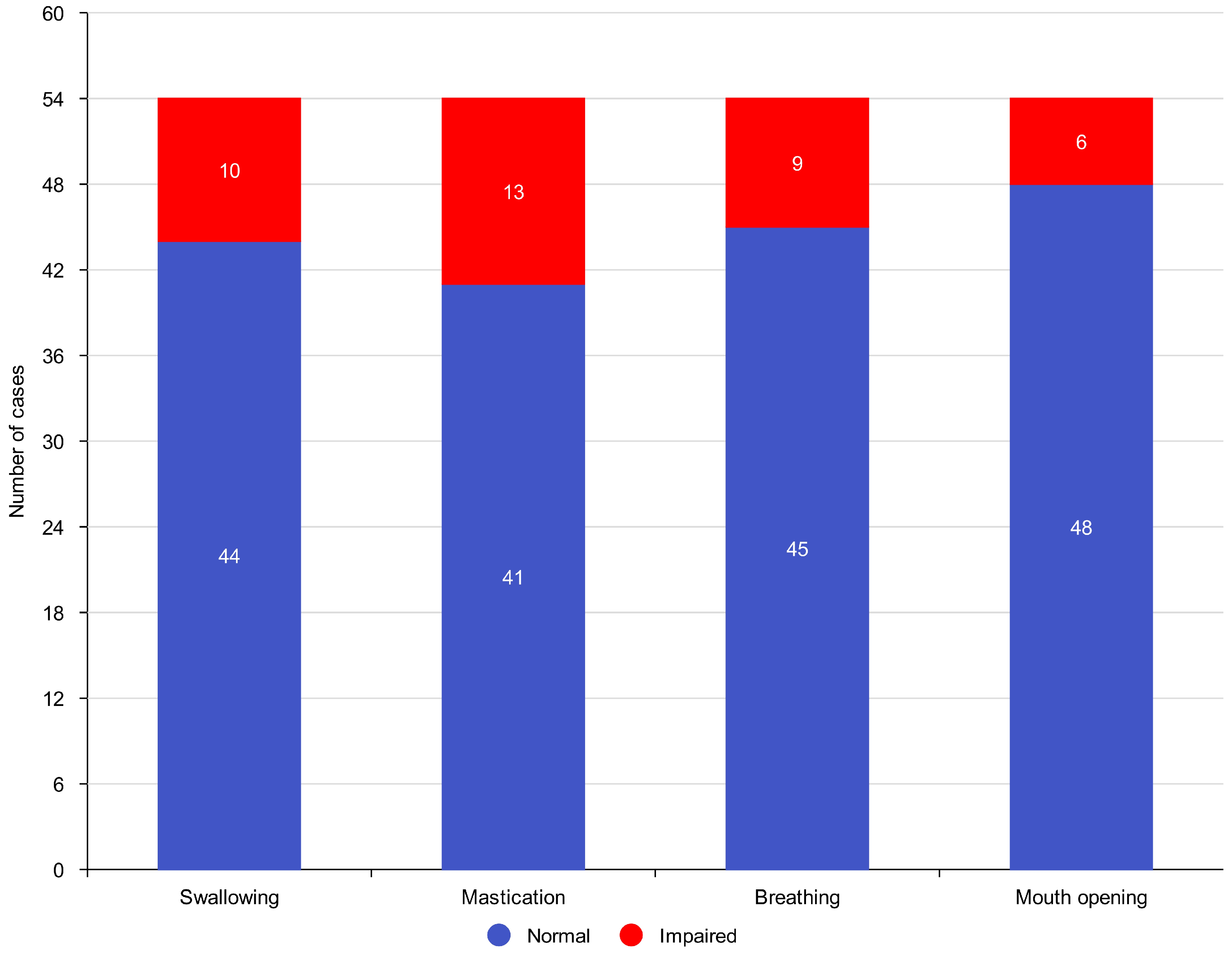

3.2. Functional Outcomes

- Normal swallowing was preserved in 44 patients (95.7%).

- Effective mastication was maintained in 41 patients (89.1%).

- Normal breathing function was observed in 45 patients (97.8%).

- Mouth opening reduction (trismus) occurred in 6 patients (13%).

3.3. Flap Viability Monitoring

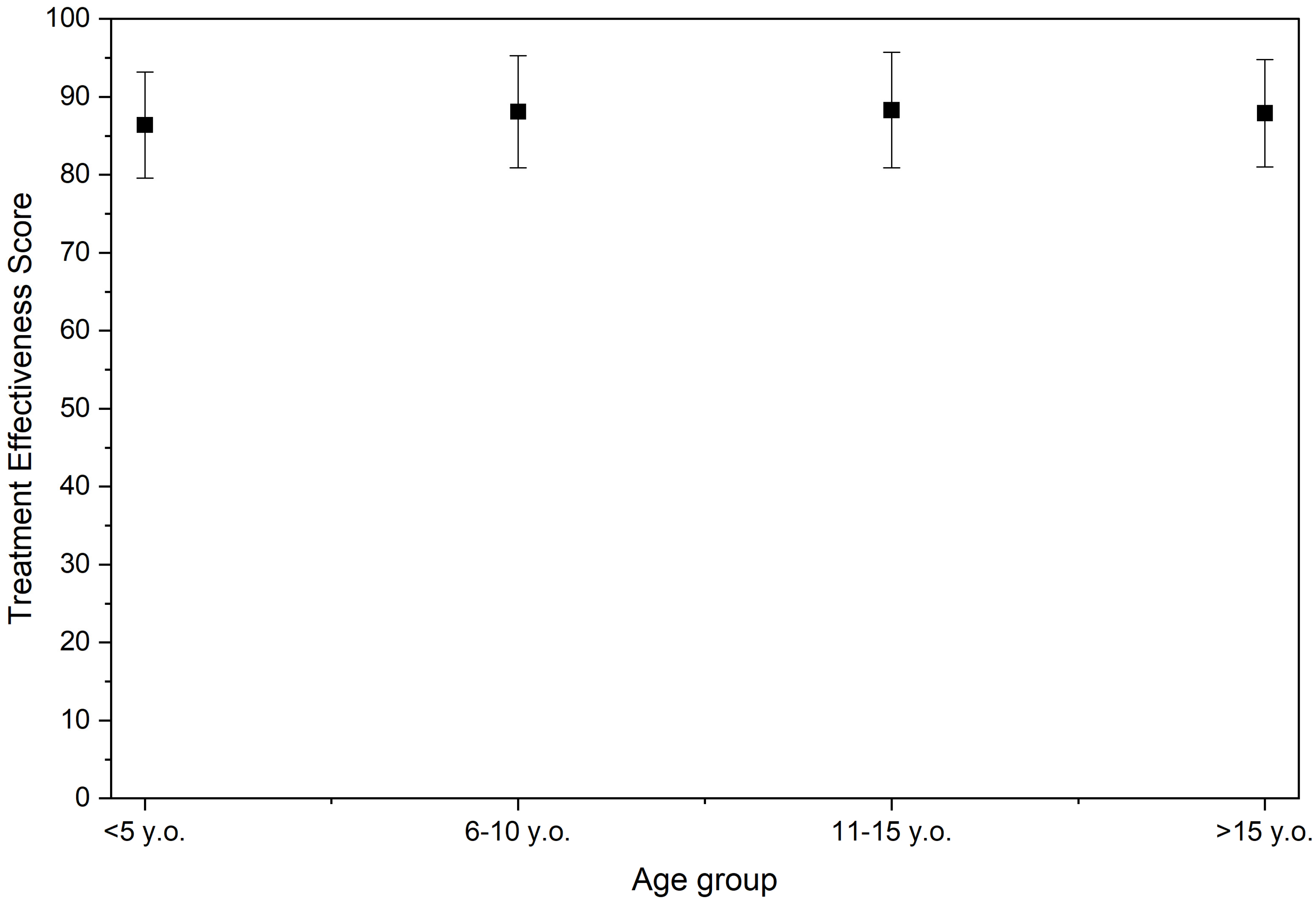

3.4. Age-Dependent Differences

- ≤5 years: 86.4 ± 6.8

- 6–10 years: 88.1 ± 7.2

- 11–15 years: 88.3 ± 7.4

- ≥16 years: 87.9 ± 6.9

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yoo, H.; Kim, B.J. History and Recent Advances in Microsurgery. Arch. Hand Microsurg. 2021, 26, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, H.R.; Skochdopole, A.J.; Alfaro Zeledon, R.; Pederson, W.C. Pediatric Microsurgery and Free-Tissue Transfer. Semin. Plast. Surg. 2023, 37, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.A.; Tamaki, A.; Thuener, J.E.; Li, S.; Fowler, N.; Lavertu, P.; Teknos, T.N.; Rezaee, R.P. Technological advancements in head and neck free tissue transfer reconstruction. Plast. Aesthet. Res. 2021, 8, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markiewicz, M.R.; Ruiz, R.L.; Pirgousis, P.; Bell, R.B.; Dierks, E.J.; Edwards, S.P.; Fernandes, R. Microvascular Free Tissue Transfer for Head and Neck Reconstruction in Children: Part I. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2016, 27, 846–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roasa, F.V.; Castañeda, S.S.; Mendoza, D.J.C. Pediatric free flap reconstruction for head and neck defects. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2018, 26, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, R.; Ringel, B.; Zissman, S.; Shapira, U.; Duek, I.; Muhanna, N.; Horowitz, G.; Zaretski, A.; Yanko, R.; Derowe, A.; et al. Free flap transfers for head and neck and skull base reconstruction in children and adolescents—Early and late outcomes. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2020, 138, 110299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lech, D.; Matysek, J.; Maksymowicz, R.; Strączek, C.; Marguła, R.; Krakowczyk, Ł.; Kozakiewicz, M.; Dowgierd, K. Maxillofacial Microvascular Free-Flap Reconstructions in Pediatric and Young Adult Patients—Outcomes and Potential Factors Influencing Success Rate. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, F.; Henderson, P.W.; Matros, E.; Cordeiro, P.G. Long-Term Growth, Functional, and Aesthetic Outcomes after Fibula Free Flap Reconstruction for Mandibulectomy Performed in Children. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2022, 10, e4449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J.H.; Rechner, B.; Tompson, B.D. Mandibular growth following reconstruction using a free fibula graft in the pediatric facial skeleton. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2005, 116, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, M.A.; Martin, J.W.; Robb, G.L.; Chang, D.W. Pediatric mandibular reconstruction using a vascularized fibula flap. Head Neck 2008, 30, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Engel-Hoek, L.; De Groot, I.J.M.; De Swart, B.J.M.; Erasmus, C.E. Feeding and Swallowing Disorders in Pediatric Neuromuscular Diseases: An Overview. J. Neuromuscul. Dis. 2015, 2, 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horii, N.; Hasegawa, Y.; Sakuramoto-Sadakane, A.; Saito, S.; Nanto, T.; Nakao, Y.; Domen, K.; Ono, T.; Kishimoto, H. Validity of a dysphagia screening test following resection for head and neck cancer. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2021, 190, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermaire, J.A.; Raaijmakers, C.P.J.; Monninkhof, E.M.; Verdonck-de Leeuw, I.M.; Terhaard, C.H.J.; Speksnijder, C.M. Factors associated with masticatory function as measured with the Mixing Ability Test in patients with head and neck cancer before and after treatment: A prospective cohort study. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 4429–4436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Atme, Y.S.; Chedid, N.; Melis, M.; Zawawi, K.H. Clinical measurement of normal maximum mouth opening in children. J. Craniomandib. Sleep Pract. 2008, 26, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.H.; Lee, W.J.; Jung, J.M.; Won, C.H.; Chang, S.E.; Lee, M.W.; Moon, I.J. Morphological characteristics of facial scars: A retrospective analysis according to scar location, onset, age, and cause. Int. Wound J. 2024, 21, e14453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, A.L.; Luebbers, H.T.; Grätz, K.W.; Obwegeser, J.A. Free flap monitoring protocol. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2010, 21, 1262–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, A.H.; Lamp, S. Current approaches to free flap monitoring. Plast. Surg. Nurs. 2014, 34, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoccali, G.; Molina, A.; Farhadi, J. Is long-term post-operative monitoring of microsurgical flaps still necessary? J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2017, 70, 996–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, A.L.D.; Luebbers, H.T.; Grätz, K.W.; Obwegeser, J.A. Factors influencing survival of free-flap in reconstruction for cancer of the head and neck: A literature review. Microsurgery 2010, 30, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Galil, K.; Mitchell, D. Postoperative monitoring of microsurgical free tissue transfers for head and neck reconstruction: A systematic review of current techniques-Part I. Non-invasive techniques. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2009, 47, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Landuyt, K.; Hamdi, M.; Blondeel, P.; Tonnard, P.; Verpaele, A.; Monstrey, S. Free perforator flaps in children. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2005, 116, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohlenz, P.; Klatt, J.; Schön, G.; Blessmann, M.; Li, L.; Schmelzle, R. Microvascular free flaps in head and neck surgery: Complications and outcome of 1000 flaps. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2012, 41, 739–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christianto, S.; Lau, A.; Li, K.Y.; Yang, W.F.; Su, Y.X. One versus two venous anastomoses in microsurgical head and neck reconstruction: A cumulative meta-analysis. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 47, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthil Murugan, M.; Ravi, P.; Mohammed Afradh, K.; Tatineni, V.; Krishnakumar Raja, V.B. Comparison of the efficacy of venous coupler and hand-sewn anastomosis in maxillofacial reconstruction using microvascular fibula free flaps: A prospective randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 47, 854–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieker, H.; Fritz Schomaker, M.C.; Flörke, C.; Karayürek, F.; Naujokat, H.; Acil, Y.; Wiltfang, J.; Gülses, A. A retrospective analysis of the surgical outcomes of different free vascularized flaps used for the reconstruction of the maxillofacial region: Hand-sewn microvascular anastomosis vs. anastomotic coupler device. J. Cranio Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 49, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yu, M.; Huang, S.; Zhang, S.; Li, W.; Zhang, D. Preliminary report of the use of a microvascular coupling device for arterial anastomoses in oral and maxillofacial reconstruction. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 58, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Wang, X.; Huang, J.; Li, J.; Ding, X.; Wu, H.; Yuan, Y.; Song, X.; Wu, Y. Mechanical versus Hand-Sewn Venous Anastomoses in Free Flap Reconstruction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2018, 141, 1272–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, L.H.; Constantinides, J.; Butler, C.E. Venous thrombosis in coupled versus sutured microvascular anastomoses. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2006, 57, 666–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkureishi, L.W.T.; Purnell, C.A.; Park, P.; Bauer, B.S.; Fine, N.A.; Sisco, M. Long-term Outcomes after Pediatric Free Flap Reconstruction. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2018, 81, 456–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upton, J.; Guo, L. Pediatric free tissue transfer: A 29-year experience with 433 transfers. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2008, 121, 1725–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, J.W.; Sweeny, L.; Carroll, W.R.; Peters, G.E.; Rosenthal, E.L. Outcomes in head and neck reconstruction by surgical site and donor site. Laryngoscope 2013, 123, 1612–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, W.; Yu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Mao, C.; Guo, C.; Yu, G.; Peng, X. Free Flap Transfer for Pediatric Head and Neck Reconstruction: What Factors Influence Flap Survival? Laryngoscope 2019, 129, 1915–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciejewski, A. O Sztuce Chirurgii Rekonstrukcyjnej; VM Media Sp z o.o. VM Group sp.k. (Grupa Via Medica): Gdańsk, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, X.F.; Peng, X. What is the price to pay for a free fibula flap? A systematic review of donor-site morbidity following free fibula flap surgery. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2012, 129, 657–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearns, M.; Ermogenous, P.; Myers, S.; Ghanem, A.M. Osteocutaneous flaps for head and neck reconstruction: A focused evaluation of donor site morbidity and patient reported outcome measures in different reconstruction options. Arch. Plast. Surg. 2018, 45, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canales, F.; Lineaweaver, W.C.; Furnas, H.; Whitney, T.; Siko, P.; Alpert, B.; Buncke, G.; Buncke, H. Microvascular tissue transfer in paediatric patients: Analysis of 106 cases. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 1991, 44, 423–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, H.M.; Spauwen, P.H.M.; Jansen, J.A. Donor-site complications in vascularized bone flap surgery. J. Investig. Surg. 2002, 15, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazar, S.; Wei, F.C.; Cheng, M.H.; Huang, W.C.; Chwei-Chin Chuang, D.; Lin, C.H. Safety and reliability of microsurgical free tissue transfers in paediatric head and neck reconstruction—A report of 72 cases. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2008, 61, 767–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaggl, A.; Bürger, H.; Virnik, S.; Schachner, P.; Chiari, F. The microvascular corticocancellous femur flap for reconstruction of the anterior maxilla in adult cleft lip, palate, and alveolus patients. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial J. 2012, 49, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, A. Reconstruction of congenital hand defects with microvascular toe transfers. Hand Clin. 1985, 1, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, J.; Akbarnia, B.A.; Hanel, D.P. Free Tissue Transfer in Children. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 1989, 9, 590–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboelatta, Y.; Aly, H. Free Tissue Transfer and Replantation in Pediatric Patients: Technical Feasibility and Outcome in a Series of 28 Patients. J. Hand Microsurg. 2016, 5, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serletti, J.M.; Schingo, V.A.; Deuber, M.A.; Carras, A.J.; Herrera, H.R.; Reale, V.F. Free tissue transfer in pediatric patients. Ann. Plast. Surg. 1996, 36, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Borowiec, M.; Lech, D.; Maksymowicz, R.; Matysek, J.; Strączek, C.; Strzelecka, A.; Kozakiewicz, M.; Krakowczyk, Ł.; Dowgierd, K. Pediatric Head & Neck Free-Flap Reconstruction Outcomes: Score-Based Effectiveness Assessment. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 1091. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031091

Borowiec M, Lech D, Maksymowicz R, Matysek J, Strączek C, Strzelecka A, Kozakiewicz M, Krakowczyk Ł, Dowgierd K. Pediatric Head & Neck Free-Flap Reconstruction Outcomes: Score-Based Effectiveness Assessment. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(3):1091. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031091

Chicago/Turabian StyleBorowiec, Maciej, Dominika Lech, Robert Maksymowicz, Jeremi Matysek, Cyprian Strączek, Aleksandra Strzelecka, Marcin Kozakiewicz, Łukasz Krakowczyk, and Krzysztof Dowgierd. 2026. "Pediatric Head & Neck Free-Flap Reconstruction Outcomes: Score-Based Effectiveness Assessment" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 3: 1091. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031091

APA StyleBorowiec, M., Lech, D., Maksymowicz, R., Matysek, J., Strączek, C., Strzelecka, A., Kozakiewicz, M., Krakowczyk, Ł., & Dowgierd, K. (2026). Pediatric Head & Neck Free-Flap Reconstruction Outcomes: Score-Based Effectiveness Assessment. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(3), 1091. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15031091