The Effects of Gamified Virtual Reality on Muscle Strength and Physical Function in the Oldest Old—A Pilot Study on Sarcopenia-Related Functional Outcomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

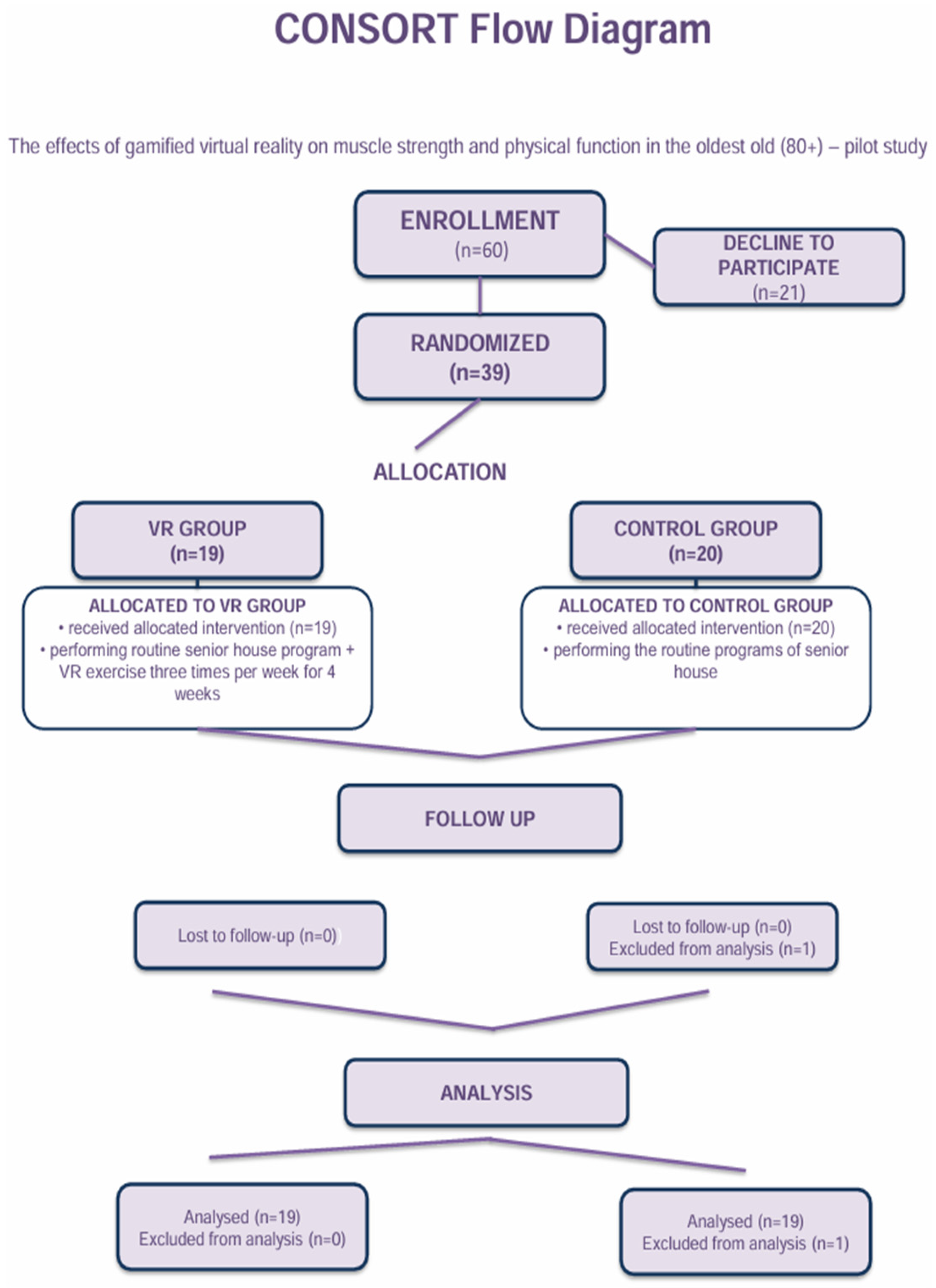

2.1. Participants

2.2. Study Design—Intervention

2.3. Outcomes Measures

2.3.1. Muscle Strength (Handgrip Strength)

2.3.2. Functional Fitness Battery

2.3.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Test | Cut-Off Point | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Handgrip strength | <27 kg (men), <16 kg (women) | European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People 2 (EWGSOP2, 2019) [4] |

| Arm curl test | <11.5 repetitions (both men and women) | Lima, A.B., Baptista, F., Henriques-Neto, D., Pinto, A.A., & Gouveia, E.R. (2023) [22] |

| 30-s chair stand test | <15 repetitions (women), <17 repetitions (men) | Sawada, S. et al. (2021) [23] |

| 8-foot up-and-go test | >10.85 s | Martinez, B.P. et al. (2015) [24] |

| 2-min step-in-place test | <60 steps | Poncumnhak, P. et al. (2023) [25] |

References

- Burns, E.R.; Stevens, J.A.; Lee, R. The direct costs of fatal and non-fatal falls among older adults—United States. J. Saf. Res. 2016, 58, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosoi, T.; Yakabe, M.; Hashimoto, S.; Akishita, M.; Ogawa, S. The roles of sex hormones in the pathophysiology of age-related sarcopenia and frailty. Reprod. Med. Biol. 2024, 23, e12569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinoshita, K.; Satake, S.; Matsui, Y.; Arai, H. Association between sarcopenia and fall risk according to the muscle mass adjustment method in Japanese older outpatients. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2021, 25, 762–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Bahat, G.; Bauer, J.; Boirie, Y.; Bruyère, O.; Cederholm, T.; Cooper, C.; Landi, F.; Rolland, Y.; Sayer, A.A.; et al. Sarcopenia: Revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 2019, 48, 16–31, Erratum in Age Ageing 2019, 48, 601. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afz046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hashimoto, S.; Hosoi, T.; Yakabe, M.; Yunoki, M.; Matsumoto, S.; Kase, Y.; Miyawaki, M.; Ishii, M.; Ogawa, S. Preventative approaches to falls and frailty. Osteoporos. Sarcopenia 2025, 11, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dent, J.E.; Morley, A.J.; Cruz-Jentoft, H.; Arai, S.B.; Kritchevsky, J.; Guralnik, J.M.; Bauer, M.; Pahor, B.C.; Clark, M.; Cesari, J.; et al. International Clinical Practice Guidelines for Sarcopenia (ICFSR): Screening, Diagnosis and Management. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2018, 22, 1148–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ethgen, O.; Beaudart, C.; Buckinx, F.; Bruyère, O.; Reginster, J.Y. The Future Prevalence of Sarcopenia in Europe: A Claim for Public Health Action. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2017, 100, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Haehling, S.; Morley, J.E.; Anker, S.D. An overview of sarcopenia: Facts and numbers on prevalence and clinical impact. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2010, 1, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, F.; Li, W. Vitamin D and Sarcopenia in the Senior People: A Review of Mechanisms and Comprehensive Prevention and Treatment Strategies. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2024, 20, 577–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kim, G.; Kim, J.H. Impact of skeletal muscle mass on metabolic health. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 35, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, J.; Lee, C.; Kim, S. Nutrition and exercise for sarcopenia treatment. Osteoporos. Sarcopenia 2025, 11, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Novak, P.; Lhotska, L. Enhancing cognitive and motor skills through personalized digital games. In Joint 20th Nordic-Baltic Conference on Biomedical Engineering & 24th Polish Conference on Biocybernetics and Biomedical Engineering (NBC PCBBE 2025); Ladyzynski, P., Pijanowska, D.G., Liebert, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; Volume 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selles, W.; Santos, E.; Romero, B.; Lunardi, A. Effectiveness of gamified exercise programs on the level of physical activity in adults with chronic diseases: A scoping review. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2024, 28, 101024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariano, J.; Marques, S.; Ramos, M.R.; Gerardo, F.; da Cunha, C.L.; Girenko, A.; De Vries, H. Too old for technology? Stereotype threat and technology use by older adults. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2022, 41, 1503–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Pérez, B.-M.; Martín-García, A.-V.; Murciano-Hueso, A. Use of serious games with older adults: Systematic literature review. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukkohovi, S.; Siira, H.; Arolaakso, S.; Miettunen, J.; Elo, S. The effectiveness of digital gaming on the functioning and activity of older people living in long-term care facilities: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2023, 35, 1595–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yan, S.; Yin, H.; Lin, D.; Mei, Z.; Ding, Z.; Wang, M.; Bai, Y.; Xu, G. Virtual reality technology improves the gait and balance function of the elderly: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch. Med. Sci. 2024, 20, 1918–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Li, X.; Xu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wan, X.; Ma, X.; Yao, G.; Li, G. Effects of Virtual Reality-Based Activities of Daily Living Rehabilitation Training in Older Adults With Cognitive Frailty and Activities of Daily Living Impairments: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2025, 26, 105397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szpak, A.; Michalski, S.C.; Loetscher, T. Exergaming With Beat Saber: An Investigation of Virtual Reality Aftereffects. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grzywacz, Ż.; Jaśniewicz, J.; Koziarska, A.; Borzucka, D.; Majorczyk, E. Virtual Reality Gaming and Its Impact and Effectiveness in Improving Eye–Hand Coordination and Attention Concentration in the Oldest-Old Population. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rikli, R.E.; Jones, C.J. Senior Fitness Test Manual, 2nd ed.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- de Lima, A.B.; Baptista, F.; Henrinques-Neto, D.; Pinto, A.d.A.; Gouveia, E.R. Symptoms of Sarcopenia and Physical Fitness through the Senior Fitness Test. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, S.; Ozaki, H.; Natsume, T.; Deng, P.; Yoshihara, T.; Nakagata, T.; Osawa, T.; Ishihara, Y.; Kitada, T.; Kimura, K.; et al. The 30-s chair stand test can be a useful tool for screening sarcopenia in elderly Japanese participants. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2021, 22, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, B.P.; Gomes, I.B.; Oliveira, C.S.; Silva Júnior, W.M.; Carvalho, V.O.; Maldonado, I.R.D. Accuracy of the Timed Up and Go test for predicting sarcopenia in elderly hospitalized patients. Clinics 2015, 70, 369–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poncumhak, P.; Amput, P.; Sangkarit, N.; Promsrisuk, T.; Srithawong, A. Predictive ability of the 2-minute step test for functional fitness in older individuals with hypertension. Ann. Geriatr. Med. Res. 2023, 27, 228–234, Correction in Ann. Geriatr. Med. Res. 2024, 28, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGrath, R.; Vincent, B.M.; Jurivich, D.A.; Hackney, K.J.; Tomkinson, G.R.; Dahl, L.J.; Clark, B.C. Handgrip Strength Asymmetry and Weakness Together Are Associated With Functional Disability in Aging Americans. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2021, 76, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohannon, R.W. Grip Strength: An Indispensable Biomarker For Older Adults. Clin. Interv. Aging 2019, 14, 1681–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Govindasamy, K.; Rao, C.R.; Chandrasekaran, B.; Parpa, K.; Granacher, U. Effects of Resistance Training on Sarcopenia Risk Among Healthy Older Adults: A Scoping Review of Physiological Mechanisms. Life 2025, 15, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Morikawa, S.; Miyawaki, M.; Nakagawa, T.; Ogawa, S.; Kase, Y. Sarcopenia prevention in older adults: Effectiveness and limitations of non-pharmacological interventions. Osteoporos. Sarcopenia 2025, 11, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talar, K.; Hernández–Belmonte, A.; Vetrovsky, T.; Steffl, M.; Kałamacka, E.; Courel-Ibáñez, J. Benefits of resistance training in early and late stages of frailty and sarcopenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, W.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, T.; Zou, L.; Wu, X.; Wang, D.; Chen, Z. Exercise Programs for Muscle Mass, Muscle Strength and Physical Performance in Older Adults with Sarcopenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Aging Dis. 2020, 11, 863–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; He, X.; Feng, Y.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Liu, Y. Effects of resistance training in healthy older people with sarcopenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur. Rev. Aging Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Song, Z.; Pan, T.; Tong, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Z. The effects of nutritional supplementation on older sarcopenic individuals who engage in resistance training: A meta-analysis. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1109789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sherrington, C.; Fairhall, N.J.; Wallbank, G.K.; Tiedemann, A.; Michaleff, Z.A.; Howard, K.; Clemson, L.; Hopewell, S.; Lamb, S.E. Exercise for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 1, CD012424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cadore, E.L.; Izquierdo, M. How to simultaneously optimize muscle strength, power, functional capacity, and cardiovascular gains in the elderly: An update. Age 2013, 35, 2329–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- da Silva Rodrigues, G.; da Silva Sobrinho, A.C.; Costa, G.P.; da Silva, L.S.L.; de Lima, J.G.R.; da Silva Gonçalves, L.; Finzeto, L.C.; Bueno Júnior, C.R. Benefits of physical exercise through multivariate analysis in sedentary adults and elderly: An analysis of physical fitness, health and anthropometrics. Exp. Gerontol. 2025, 200, 112669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, P.J.; Hsu, N.W.; Lee, M.J.; Lin, Y.Y.; Tsai, C.C.; Lin, W.S. Physical fitness and its correlation with handgrip strength in active community-dwelling older adults. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Molina, K.I.; Ricci, N.A.; de Moraes, S.A.; Perracini, M.R. Virtual reality using games for improving physical functioning in older adults: A systematic review. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2014, 11, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmak, D.; Angın, E.; Iyigun, G. Effects of Immersive Virtual Reality on Physical Function, Fall-Related Outcomes, Fatigue, and Quality of Life in Older Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitjamnogchai, C.; Yuenyongchaiwat, K.; Sermsinsaithong, N.; Tavonudomgit, W.; Mahawong, L.; Buranapuntalug, S.; Thanawattano, C. Home-Based Virtual Reality Exercise and Resistance Training for Enhanced Cardiorespiratory Fitness in Community-Dwelling Older People with Sarcopenia: A Randomized, Double-Blind Controlled Trial. Life 2025, 15, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Ali, N.M.; Mhd Salim, M.H.; Rezaldi, M.Y. A Literature Review of Virtual Reality Exergames for Older Adults: Enhancing Physical, Cognitive, and Social Health. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokgöz, P.; Stampa, S.; Wähnert, D.; Vordemvenne, T.; Dockweiler, C. Virtual Reality in the Rehabilitation of Patients with Injuries and Diseases of Upper Extremities. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chan, L.P.P.; Cheng, Y.; Ng, J.Y.H.; Zheng, Z.; Cheing, G.L.Y. A Review of Virtual Reality Technology in Exercise Training for Older Adults. J. Endocrinol. Thyroid Res. 2022, 6, 555694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Huang, Y.; Yan, J.; Li, T.; Wang, Y. Anti-inflammatory diet and low muscle mass among older adults: A cohort study based on clhls. Geriatr. Nurs. 2025, 64, 103378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Z. Association between the dietary inflammatory index and sarcopenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1100918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Groups (n) | Age (Years) | Sex (Women/Men) | Weight (kg) | Height (cm) | BMI (kg/m2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All cases (38) | 87.2 (±6.3) | 29/9 | 68 (±14.5) | 157.4 (±10.2) | 27.7 (±6.4) |

| VR group (19) | 88.0 (±6.4) | 14/5 | 70.8 (±8.3) | 161.4 (±8.3) | 27.2 (±6.6) |

| Control group (19) | 86.4 (±6.3) | 15/4 | 65.1(±12.2) | 153.5 (±10.6) | 28.2 (±6.4) |

| Parameters Related to Sarcopenia Risk | Groups | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VR Group T0 (Before) | VR Group T1 (After) | Control Group T0 (Before) | Control Group T1 (After) | ||

| Handgrip strength (kg) | Mean (SD) | 17.9 (5.9) | 18.7 (5.6) | 17.8 (4.36) | 17.2 (4.9) |

| Median (Q1-Q3) | 16.8 (15.2–18.5) | 17.9 (15.2–20.1) | 16.4 (14.9–20.9) | 15.2 (13.8–20.7) | |

| Difference T0 vs. T1 | 0.8 ↑ | 0.6 ↓ | |||

| Sarcopenia risk (n;%) # | 8 (42.1) | 7 (36.8) | 14 (73.7) | 13 (68.4) | |

| Arm curl test (n) | Mean (SD) | 14.2 (5.6) | 18.5 (5.0) | 10.3 (4.4) | 10.8 (3.8) |

| Median (Q1–Q3) | 14.0 (11–19.5) | 18.0 (14.5–22.5) | 9.0 (7.5–13) | 11.0 (8–12.5) | |

| Difference T0 vs. T1 | 4.3 ↑ | 0.5 ↑ | |||

| Sarcopenia risk (n;%) # | 6 (31.6) | 1 (5.3) | 13 (68.4) | 10 (52.6) | |

| 30-s chair stand (n) | Mean (SD) | 9.32 (4.0) | 12.5 (5.5) | 4.16 (3.7) | 4.11 (4.3) |

| Median (Q1–Q3) | 9.0 (8.0–12.0) | 14.0 (9.5–16.5) | 3.0 (2.0–5.5) | 3.0 (0.0–7.0) | |

| Difference T0 vs. T1 | 5.0 ↑ | 0.0 = | |||

| Sarcopenia risk (n;%) # | 19 (100.0) | 14 (73.7) | 19 (100.0) | 19 (100.0) | |

| 8-foot up-and-go (n) | Mean (SD) | 18.7 (16.2) | 15.9 (10.7) | 15.3 (16.2) | 14.9 (16.5) |

| Median (Q1–Q3) | 15.5 (9.02–17.9) | 12.5 (9.43–19.1) | 16.2 (0.0–26.6) | 16.5 (0.0–26.9) | |

| Difference T0 vs. T1 | 2.8 ↓ | 0.4 ↓ | |||

| Sarcopenia risk (n;%) # | 5 (26.3) | 6 (31.6) | 9 (47.4) | 7 (36.8) | |

| 2-min step-in-place (n) | Mean (SD) | 74.7 (33.2) | 85.8 (30.7) | 42.2 (41.5) | 53.2 (48.8) |

| Median (Q1–Q3) | 75.0 (50.0–97.5) | 94.0 (73.0–106.0) | 41.5 (0.0–83.5) | 48.4 (0.0–91.0) | |

| Difference T0 vs. T1 | 11.1 ↑ | 11.0 ↑ | |||

| Sarcopenia risk (n;%) # | 8 (42.1) | 2 (10.5) | 12 (63.2) | 10 (52.6) | |

| Statistical Analyses—Linear Mixed Model | |||||

| Time/Group | EMM (95%CI) | Effect | F1,36 | p Value | |

| Handgrip strength [kg] | T0 VR | 17.9 (15.6–20.3) | Time | 0.100 | 0.754 |

| T1 VR | 18.7 (16.4–21.0) | Group | 0.219 | 0.643 | |

| T0 control | 17.8 (15.5–20.2) | Time × group | 4.684 | 0.037 | |

| T1 control | 17.2 (14.9–19.6) | ||||

| Arm curl test (n) | T0 VR | 14.2 (12.0–16.3) | Time | 10.161 | 0.003 |

| T1 VR | 18.5 (16.4–20.7) | Group | 18.701 | <0.001 | |

| T0 control | 10.3 (8.2–12.4) | Time × group | 6.574 | 0.015 | |

| T1 control | 10.8 (8.7–12.9) | ||||

| 30-s chair stand (n) | T0 VR | 9.3 (7.3–11.3) | Time | 21.211 | <0.001 |

| T1 VR | 12.5 (10.5–14.5) | Group | 23.641 | <0.001 | |

| T0 control | 4.2 (2.2–6.1) | Time × group | 22.674 | <0.001 | |

| T1 control | 4.1 (2.1–6.1) | ||||

| 8-foot up-and-go (n) | T0 VR | 18.7 (11.9–25.4) | Time | 2.004 | 0.165 |

| T1 VR | 15.9 (9.1–22.6) | Group | 0.201 | 0.657 | |

| T0 control | 15.3 (8.6–22.1) | Time × group | 1.103 | 0.301 | |

| T1 control | 14.9 (8.1–21.7) | ||||

| 2-min step-in-place (n) | T0 VR | 74.7 (57.1–92.2) | Time | 0.100 | 0.754 |

| T1 VR | 85.7 (68.2–103.4) | Group | 0.219 | 0.643 | |

| T0 control | 42.2 (24.6–59.7) | Time × group | 4.684 | 0.037 | |

| T1 control | 53.2 (35.6–70.7) | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Grzywacz, Ż.; Jaśniewicz, J.; Koziarska, A.; Macierzyńska, J.; Majorczyk, E. The Effects of Gamified Virtual Reality on Muscle Strength and Physical Function in the Oldest Old—A Pilot Study on Sarcopenia-Related Functional Outcomes. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 621. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020621

Grzywacz Ż, Jaśniewicz J, Koziarska A, Macierzyńska J, Majorczyk E. The Effects of Gamified Virtual Reality on Muscle Strength and Physical Function in the Oldest Old—A Pilot Study on Sarcopenia-Related Functional Outcomes. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(2):621. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020621

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrzywacz, Żaneta, Justyna Jaśniewicz, Anna Koziarska, Joanna Macierzyńska, and Edyta Majorczyk. 2026. "The Effects of Gamified Virtual Reality on Muscle Strength and Physical Function in the Oldest Old—A Pilot Study on Sarcopenia-Related Functional Outcomes" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 2: 621. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020621

APA StyleGrzywacz, Ż., Jaśniewicz, J., Koziarska, A., Macierzyńska, J., & Majorczyk, E. (2026). The Effects of Gamified Virtual Reality on Muscle Strength and Physical Function in the Oldest Old—A Pilot Study on Sarcopenia-Related Functional Outcomes. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(2), 621. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020621