Dermoscopy-Guided High-Frequency Ultrasound Imaging of Subcentimeter Cutaneous and Subcutaneous Neurofibromas in Patients with Neurofibromatosis Type 1

Abstract

1. Introduction

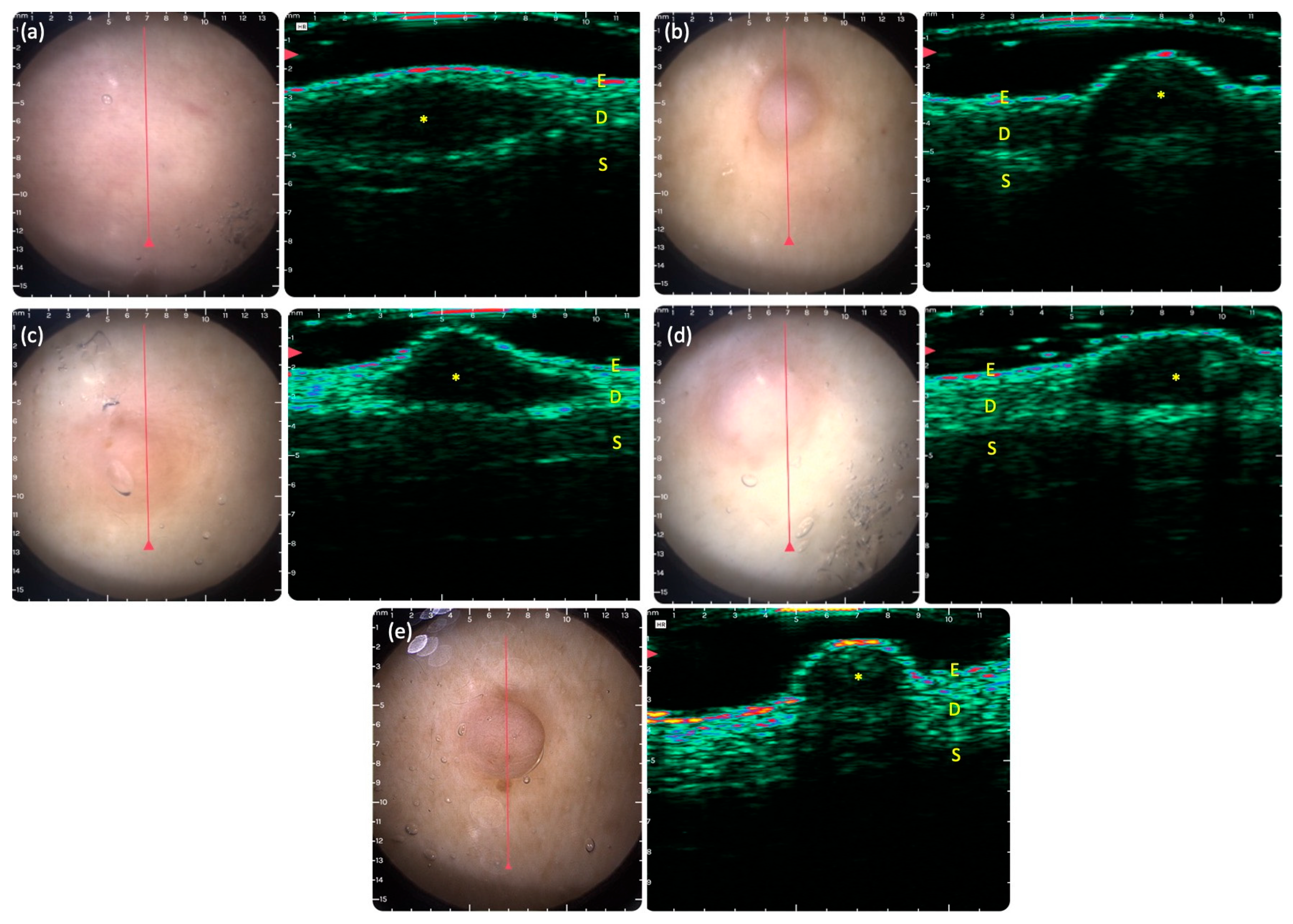

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2. DG-HFUS Imaging

3. Results

3.1. Patient and Lesion Characteristics

3.2. Clinical Presentation

3.3. DG-HFUS Imaging of Neurofibromas

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CALM | café-au-lait macules |

| CNV | copy number variation |

| DG-HFUS | dermoscopy-guided high-frequency ultrasound |

| EFSUMB | European Federation of Societies for Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology |

| HFUS | high-frequency ultrasound |

| LC-OCT | line-field confocal optical coherence tomography |

| MPNST | malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| MSI | multispectral imaging |

| NF1 | neurofibromatosis type 1 |

| OCT | optical coherence tomography |

| QOL | quality of life |

| RCM | reflectance confocal microscopy |

References

- Miller, D.T.; Freedenberg, D.; Schorry, E.; Ullrich, N.J.; Viskochil, D.; Korf, B.R.; Council on Genetics; American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics; Chen, E.; Trotter, T.L.; et al. Health Supervision for Children with Neurofibromatosis Type 1. Pediatrics 2019, 143, e20190660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirbe, A.C.; Gutmann, D.H. Neurofibromatosis type 1: A multidisciplinary approach to care. Lancet Neurol. 2014, 13, 834–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, A.E.; Belzberg, A.J.; Crawford, J.R.; Hirbe, A.C.; Wang, Z.J. Treatment decisions and the use of MEK inhibitors for children with neurofibromatosis type 1-related plexiform neurofibromas. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutmann, D.H.; Ferner, R.E.; Listernick, R.H.; Korf, B.R.; Wolters, P.L.; Johnson, K.J. Neurofibromatosis type 1. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2017, 3, 17004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabata, M.M.; Li, S.; Knight, P.; Bakker, A.; Sarin, K.Y. Phenotypic heterogeneity of neurofibromatosis type 1 in a large international registry. JCI Insight 2020, 5, e136262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veres, K.; Bene, J.; Hadzsiev, K.; Garami, M.; Pálla, S.; Happle, R.; Medvecz, M.; Szalai, Z.Z. Superimposed Mosaicism in the Form of Extremely Extended Segmental Plexiform Neurofibroma Caused by a Novel Pathogenic Variant in the NF1 Gene. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozarslan, B.; Russo, T.; Argenziano, G.; Santoro, C.; Piccolo, V. Cutaneous Findings in Neurofibromatosis Type 1. Cancers 2021, 13, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; McKay, R.M.; Lee, S.Y.; Romo, C.G.; Blakeley, J.O.; Haniffa, M.; Serra, E.; Steensma, M.R.; Largaespada, D.; Le, L.Q. Cutaneous Neurofibroma Heterogeneity: Factors that Influence Tumor Burden in Neurofibromatosis Type 1. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2023, 143, 1369–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solares, I.; Vinal, D.; Morales-Conejo, M. Diagnostic and follow-up protocol for adult patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 in a Spanish reference unit. Rev. Clínica Española (Engl. Ed.) 2022, 222, 486–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legius, E.; Messiaen, L.; Wolkenstein, P.; Pancza, P.; Avery, R.A.; Berman, Y.; Blakeley, J.; Babovic-Vuksanovic, D.; Cunha, K.S.; Ferner, R. Revised diagnostic criteria for neurofibromatosis type 1 and Legius syndrome: An international consensus recommendation. Genet. Med. 2021, 23, 1506–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legius, E.; Brems, H. Genetic basis of neurofibromatosis type 1 and related conditions, including mosaicism. Childs Nerv. Syst. 2020, 36, 2285–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wimmer, K.; Yao, S.; Claes, K.; Kehrer-Sawatzki, H.; Tinschert, S.; De Raedt, T.; Legius, E.; Callens, T.; Beiglböck, H.; Maertens, O. Spectrum of single- and multiexon NF1 copy number changes in a cohort of 1,100 unselected NF1 patients. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2005, 45, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méni, C.; Sbidian, E.; Moreno, J.C.; Lafaye, S.; Buffard, V.; Goldzal, S.; Wolkenstein, P.; Valeyrie-Allanore, L. Treatment of neurofibromas with a carbon dioxide laser: A retrospective cross-sectional study of 106 patients. Dermatology 2015, 230, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Y.Z.; Al-Niaimi, F.; Ferguson, J.; August, P.J.; Madan, V. Carbon dioxide laser treatment of cutaneous neurofibromas. Dermatol. Ther. 2012, 2, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roenigk, R.K.; Ratz, J.L. CO2 laser treatment of cutaneous neurofibromas. Dermatol. Surg. 1987, 13, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwakil, T.F.; Samy, N.A.; Elbasiouny, M.S. Non-excision treatment of multiple cutaneous neurofibromas by laser photocoagulation. Lasers Med. Sci. 2008, 23, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richey, P.; Funk, M.; Sakamoto, F.; Plotkin, S.; Ly, I.; Jordan, J.; Muzikansky, A.; Roberts, J.; Farinelli, W.; Levin, Y. Noninvasive treatment of cutaneous neurofibromas (cNFs): Results of a randomized prospective, direct comparison of four methods. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2024, 90, 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutterodt, C.; Mohan, A.; Kirkpatrick, N. The use of electrodessication in the treatment of cutaneous neurofibromatosis: A retrospective patient satisfaction outcome assessment. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2016, 69, 765–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beverly, S.; Goldberg, D.; Foley, E. Shave removal plus electrodessication for treatment of cutaneous neurofibromas: A quick, cost effective, and cosmetically acceptable removal technique. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2012, 66, AB212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-H.; Roh, S.-G.; Lee, N.-H.; Yang, K.-M. Radiofrequency ablation and excision of multiple cutaneous lesions in neurofibromatosis type 1. Arch. Plast. Surg. 2013, 40, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baujat, B.; Krastinova-Lolov, D.; Blumen, M.; Baglin, A.-C.; Coquille, F.; Chabolle, F. Radiofrequency in the treatment of craniofacial plexiform neurofibromatosis: A pilot study. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2006, 117, 1261–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrowczynski, O.; Mau, C.; Nguyen, D.T.; Sarwani, N.; Rizk, E.; Harbaugh, K.; Mrowczynski, O.D. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation for the treatment of peripheral nerve sheath tumors: A case report and review of the literature. Cureus 2018, 10, e2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Hyun, D.J.; Piquette, R.; Beaumont, C.; Germain, L.; Larouche, D. 27.12 MHz radiofrequency ablation for benign cutaneous lesions. BioMed Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 6016943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latham, K.; Buchanan, E.P.; Suver, D.; Gruss, J.S. Neurofibromatosis of the head and neck: Classification and surgical management. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2015, 135, 845–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikuta, K.; Nishida, Y.; Sakai, T.; Koike, H.; Ito, K.; Urakawa, H.; Imagama, S. Surgical treatment and complications of deep-seated nodular plexiform neurofibromas associated with neurofibromatosis type 1. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 5695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamseddin, B.H.; Le, L.Q. Management of cutaneous neurofibroma: Current therapy and future directions. Neurooncol. Adv. 2019, 2, i107–i116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamseddin, B.H.; Hernandez, L.; Solorzano, D.; Vega, J.; Le, L.Q. Robust surgical approach for cutaneous neurofibroma in neurofibromatosis type 1. JCI Insight 2019, 4, e128881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, A.M.; Wolters, P.L.; Dombi, E.; Baldwin, A.; Whitcomb, P.; Fisher, M.J.; Weiss, B.; Kim, A.; Bornhorst, M.; Shah, A.C.; et al. Selumetinib in Children with Inoperable Plexiform Neurofibromas. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1430–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.; Dib, A.; Beaini, S.; Saad, C.; Faraj, S.; El Joueid, Y.; Kotob, Y.; Saoudi, L.; Emmanuel, N. Neurofibromatosis type 1 system-based manifestations and treatments: A review. Neurol. Sci. 2023, 44, 1931–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirk, B.; Olasz, E.; Kumar, S.; Basel, D.; Whelan, H. Photodynamic Therapy for Benign Cutaneous Neurofibromas Using. Aminolevulinic Acid. Topical Application and 633 nm Red Light Illumination. Photobiomodulation Photomed. Laser Surg. 2021, 39, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarin, K.Y.; Bradshaw, M.; O’Mara, C.; Shahryari, J.; Kincaid, J.; Kempers, S.; Tu, J.H.; Dhawan, S.; DuBois, J.; Wilson, D.; et al. Effect of NFX-179 MEK inhibitor on cutaneous neurofibromas in persons with neurofibromatosis type 1. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadk4946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakos, R.M.; Blumetti, T.P.; Roldán-Marín, R.; Salerni, G. Noninvasive Imaging Tools in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Skin Cancers. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2018, 19, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, N.N.; Boostani, M.; Farkas, K.; Bánvölgyi, A.; Lőrincz, K.; Posta, M.; Lihacova, I.; Lihachev, A.; Medvecz, M.; Holló, P.; et al. Optically Guided High-Frequency Ultrasound Shows Superior Efficacy for Preoperative Estimation of Breslow Thickness in Comparison with Multispectral Imaging: A Single-Center Prospective Validation Study. Cancers 2024, 16, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boostani, M.; Bozsányi, S.; Suppa, M.; Cantisani, C.; Lőrincz, K.; Bánvölgyi, A.; Holló, P.; Wikonkál, N.M.; Huss, W.J.; Brady, K.L.; et al. Novel imaging techniques for tumor margin detection in basal cell carcinoma: A systematic scoping review of FDA and EMA-approved imaging modalities. Int. J. Dermatol. 2025, 64, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boostani, M.; Pellacani, G.; Wortsman, X.; Suppa, M.; Goldust, M.; Cantisani, C.; Pietkiewicz, P.; Lőrincz, K.; Bánvölgyi, A.; Wikonkál, N.M. FDA and EMA-approved noninvasive imaging techniques for basal cell carcinoma subtyping: A systematic review. JAAD Int. 2025, 21, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plorina, E.V.; Saulus, K.; Rudzitis, A.; Kiss, N.; Medvecz, M.; Linova, T.; Bliznuks, D.; Lihachev, A.; Lihacova, I. Multispectral Imaging Analysis of Skin Lesions in Patients with Neurofibromatosis Type 1. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boostani, M.; Bánvölgyi, A.; Zouboulis, C.C.; Goldfarb, N.; Suppa, M.; Goldust, M.; Lőrincz, K.; Kiss, T.; Nádudvari, N.; Holló, P.; et al. Large language models in evaluating hidradenitis suppurativa from clinical images. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2025, 39, e1052–e1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boostani, M.; Bánvölgyi, A.; Goldust, M.; Cantisani, C.; Pietkiewicz, P.; Lőrincz, K.; Holló, P.; Wikonkál, N.M.; Paragh, G.; Kiss, N. Diagnostic Performance of GPT-4o and Gemini Flash 2.0 in Acne and Rosacea. Int. J. Dermatol. 2025, 64, 1881–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boostani, M.; Pellacani, G.; Goldust, M.; Nádudvari, N.; Rátky, D.; Cantisani, C.; Lőrincz, K.; Bánvölgyi, A.; Wikonkál, N.M.; Paragh, G.; et al. Diagnosing Actinic Keratosis and Squamous Cell Carcinoma With Large Language Models From Clinical Images. Int. J. Dermatol. 2025; online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boostani, M.; Wortsman, X.; Pellacani, G.; Cantisani, C.; Suppa, M.; Mohos, A.; Goldust, M.; Pietkiewicz, P.; Bánvölgyi, A.; Holló, P.; et al. Dermoscopy-guided high-frequency ultrasound for preoperative assessment of basal cell carcinoma lateral margins: A pilot study. Br. J. Dermatol. 2025, 193, 572–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csány, G.; Gergely, L.H.; Kiss, N.; Szalai, K.; Lőrincz, K.; Strobel, L.; Csabai, D.; Hegedüs, I.; Marosán-Vilimszky, P.; Füzesi, K.; et al. Preliminary Clinical Experience with a Novel Optical-Ultrasound Imaging Device on Various Skin Lesions. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfageme, F.; Wortsman, X.; Catalano, O.; Roustan, G.; Crisan, M.; Crisan, D.; Gaitini, D.E.; Cerezo, E.; Badea, R. European Federation of Societies for Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology (EFSUMB) Position Statement on Dermatologic Ultrasound. Ultraschall Med. 2021, 42, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, Y.; Ren, W.W.; Yang, F.Y.; Li, L.; Wu, L.; Dan Shan, D.; Chen, Z.T.; Wang, L.F.; Wang, Q.; Guo, L.H. Diagnostic value of high-frequency ultrasound (HFUS) in evaluation of subcutaneous lesions. Skin. Res. Technol. 2023, 29, e13464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Wang, C.; Wang, D.; Li, X.; Guo, W.; Chen, T. Malignant and Benign Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors in a Single Center: Value of Clinical and Ultrasound Features for the Diagnosis of Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor Compared with Magnetic Resonance Imaging. J. Ultrasound Med. 2024, 43, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, C.; Zhou, H.; Dong, Y.; Alhaskawi, A.; Hasan Abdullah Ezzi, S.; Wang, Z.; Lai, J.; Goutham Kota, V.; Hasan Abdulla Hasan Abdulla, M.; Lu, H. Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors: Latest Concepts in Disease Pathogenesis and Clinical Management. Cancers 2023, 15, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veres, K.; Nagy, B.; Ember, Z.; Bene, J.; Hadzsiev, K.; Medvecz, M.; Szabó, L.; Szalai, Z.Z. Increased Phenotype Severity Associated with Splice-Site Variants in a Hungarian Pediatric Neurofibromatosis 1 Cohort: A Retrospective Study. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafailidis, V.; Kaziani, T.; Theocharides, C.; Papanikolaou, A.; Rafailidis, D. Imaging of the malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour with emphasis οn ultrasonography: Correlation with MRI. J. Ultrasound. 2014, 17, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahya, H.; Sani, H. Eruptive Neurofibromas in Pregnancy. Ann. Afr. Med. 2020, 19, 150–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Well, L.; Jaeger, A.; Kehrer-Sawatzki, H.; Farschtschi, S.; Avanesov, M.; Sauer, M.; de Sousa, M.T.; Bannas, P.; Derlin, T.; Adam, G.; et al. The effect of pregnancy on growth-dynamics of neurofibromas in Neurofibromatosis type 1. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, B.; Ganier, C.; Du-Harpur, X.; Harun, N.; Watt, F.; Patalay, R.; Lynch, M.D. Applications and future directions for optical coherence tomography in dermatology. Br. J. Dermatol. 2021, 184, 1014–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, A.; Markowitz, O. Introduction to reflectance confocal microscopy and its use in clinical practice. JAAD Case Rep. 2018, 4, 1014–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilișanu, M.-A.; Moldoveanu, F.; Moldoveanu, A. Multispectral Imaging for Skin Diseases Assessment—State of the Art and Perspectives. Sensors 2023, 23, 3888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacot, L.; Burin des Roziers, C.; Laurendeau, I.; Briand-Suleau, A.; Coustier, A.; Mayard, T.; Tlemsani, C.; Faivre, L.; Thomas, Q.; Rodriguez, D.; et al. One NF1 Mutation may Conceal Another. Genes 2019, 10, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landry, J.P.; Schertz, K.L.; Chiang, Y.J.; Bhalla, A.D.; Yi, M.; Keung, E.Z.; Scally, C.P.; Feig, B.W.; Hunt, K.K.; Roland, C.L.; et al. Comparison of Cancer Prevalence in Patients With Neurofibromatosis Type 1 at an Academic Cancer Center vs in the General Population From 1985 to 2020. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e210945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Symptoms | The Number and Percentage of Affected Patients |

|---|---|

| CALM | 11 (79%) |

| Axillary and inguinal freckling | 12 (86%) |

| Cutaneous and subcutaneous neurofibroma | 14 (100%) |

| Plexiform neurofibroma | 6 (43%) |

| Lisch-nodule | 11 (79%) |

| Scoliosis | 5 (36%) |

| Malignancy | 3 (21%) |

| Patients | CALM | Axillary or Inguinal Freckling | NF | Optic Glioma | Lisch Nodule | Skeletal Abnormality | NF1 Variant | Family History | Number of NF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NFP1 | >6 | ✓ | >2 | - | >2 | - | pos | neg | 4 |

| NFP2 | >6 | ✓ | >2 | - | >2 | - | pos | pos | 4 |

| NFP3 | - | - | >2 | - | - | - | pos | neg | 7 |

| NFP4 | - | - | >2 | - | - | - | pos | neg | 7 |

| NFP5 | >6 | ✓ | >2 | - | >2 | - | pos | neg | 8 |

| NFP6 | >6 | ✓ | >2 | - | >2 | - | pos | neg | 9 |

| NFP7 | >6 | ✓ | >2 | - | >2 | - | pos | pos | 10 |

| NFP8 | >6 | ✓ | >2 | - | >2 | - | pos | neg | 6 |

| NFP9 | >6 | ✓ | >2 | - | - | - | pos | pos | 5 |

| NFP10 | >6 | ✓ | >2 | - | >2 | - | pos | neg | 8 |

| NFP11 | >6 | ✓ | >2 | - | >2 | - | pos | neg | 7 |

| NFP12 | >6 | ✓ | >2 | - | >2 | - | pos | pos | 13 |

| NFP13 | >6 | ✓ | >2 | - | >2 | - | pos | pos | 3 |

| NFP14 | - | ✓ | >2 | - | >2 | - | pos | pos | 9 |

| Patients | Sex Assigned at Birth | Age (Year) | Onset of Symptoms | Cutaneous Symptoms | Extracutaneous Symptoms | Comorbidites |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NFP1 | male | 50 | childhood | CALM, freckling, neurofiroma | Lisch nodules, hypertension | asthma bronchiale |

| NFP2 | male | 70 | childhood | CALM, freckling, neurofiroma | Lisch nodules, pheochromocytoma, hypertension | asthma bronchiale, BPH, nephrolithiasis, gastritis chronica |

| NFP3 | female | 58 | adulthood | neurofibroma | hypetension | struma nodosa |

| NFP4 | female | 52 | adulthood | neurofibroma, nevus anemicus | Breast cancer, adrenal adenoma | - |

| NFP5 | female | 34 | adolescence | CALM, freckling, neurofiroma | Lisch-nodules | migraine, myopia |

| NFP6 | female | 38 | adolescence | CALM, freckling, neurofiroma | Lisch-nodules | cholelithiasis, gastric ulcer |

| NFP7 | male | 21 | childhood | CALM, freckling, neurofiroma | Lisch nodules, scoliosis | - |

| NFP8 | male | 19 | childhood | CALM, freckling, neurofibroma, juvenile xanthogranuloma | Lisch nodules, scoliosis | - |

| NFP9 | female | 35 | childhood | CALM, freckling, neurofibroma | scoliosis | cataracta, myopia, allergic rhinitis |

| NFP10 | male | 31 | childhood | CALM, freckling, neurofibroma | Lisch nodules | myopia, strabismus |

| NFP11 | male | 73 | adolescence | CALM, freckling, neurofibroma | Lisch nodules, scoliosis, hypertension, GIST | contact dermatitis |

| NFP12 | female | 56 | adolescence | CALM, freckling, neurofibroma | Lisch-nodules | hyperlipidemia |

| NFP13 | female | 47 | childhood | CALM, freckling, neurofibroma | Lisch nodules, scoliosis | spina bifida |

| NFP14 | female | 39 | childhood | freckling, neurofibroma, nevus anemicus | Lisch nodules | - |

| Location | Dermis | 79/100 (79%) |

| Subcutis | 21/100 (21%) | |

| Shape | Round | 28/100 (28%) |

| Ovoid | 63/100 (63%) | |

| Spiked | 9/100 (9%) | |

| Global echogenicity | Hypoechoic | 100/100 (100%) |

| Hyperechoic | 0/100 (0%) | |

| Echogenicity | Homogenous | 62/100 (62%) |

| Heterogenous | 38/100 (38%) | |

| Contour | Well-defined | 57/100 (57%) |

| Poorly defined | 43/100 (43%) | |

| Posterior acoustic feature | Enhancement | 3/100 (3%) |

| Shadowing | 10/100 (10%) | |

| Surface | Protruding | 58/100 (58%) |

| Flat | 42/100 (42%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kerekes, K.; Boostani, M.; Metyovinyi, Z.; Kiss, N.; Medvecz, M. Dermoscopy-Guided High-Frequency Ultrasound Imaging of Subcentimeter Cutaneous and Subcutaneous Neurofibromas in Patients with Neurofibromatosis Type 1. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 475. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020475

Kerekes K, Boostani M, Metyovinyi Z, Kiss N, Medvecz M. Dermoscopy-Guided High-Frequency Ultrasound Imaging of Subcentimeter Cutaneous and Subcutaneous Neurofibromas in Patients with Neurofibromatosis Type 1. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(2):475. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020475

Chicago/Turabian StyleKerekes, Krisztina, Mehdi Boostani, Zseraldin Metyovinyi, Norbert Kiss, and Márta Medvecz. 2026. "Dermoscopy-Guided High-Frequency Ultrasound Imaging of Subcentimeter Cutaneous and Subcutaneous Neurofibromas in Patients with Neurofibromatosis Type 1" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 2: 475. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020475

APA StyleKerekes, K., Boostani, M., Metyovinyi, Z., Kiss, N., & Medvecz, M. (2026). Dermoscopy-Guided High-Frequency Ultrasound Imaging of Subcentimeter Cutaneous and Subcutaneous Neurofibromas in Patients with Neurofibromatosis Type 1. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(2), 475. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020475