Monocyte-Driven Systemic Biomarkers and Survival After Pulmonary Metastasectomy in Metachronous Lung-Limited Oligometastatic Disease: A Retrospective Single-Center Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

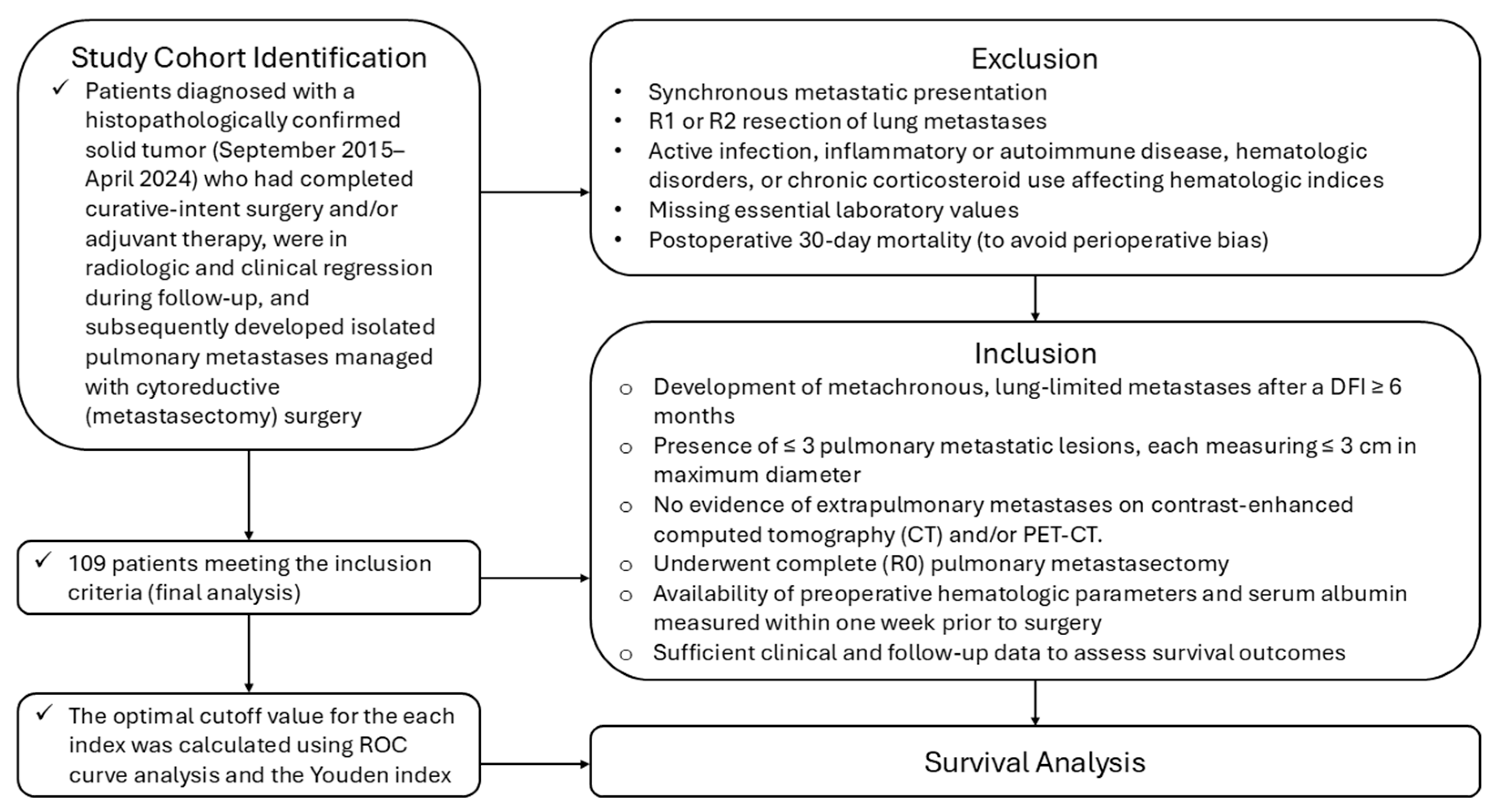

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Study Population

2.2.1. Definition of Metachronous Lung-Limited Oligometastatic Disease

2.2.2. Inclusion Criteria

- Histologically confirmed primary solid tumor of any organ origin.

- Development of metachronous, lung-limited metastases after a DFI ≥ 6 months.

- Presence of ≤3 pulmonary metastatic lesions, each measuring ≤3 cm in maximum diameter.

- No evidence of extrapulmonary metastases on Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) and/or positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT).

- Underwent complete (R0) pulmonary metastasectomy.

- Availability of preoperative hematologic parameters and serum albumin measured within one week prior to surgery.

- Sufficient clinical and follow-up data to assess survival outcomes.

2.2.3. Exclusion Criteria

- Synchronous metastatic presentation.

- R1 or R2 resection of lung metastases.

- Active infection, inflammatory or autoimmune disease, hematologic disorders, and chronic corticosteroid use affect hematologic indices.

- Missing essential laboratory values.

- Postoperative 30-day mortality (to avoid perioperative bias).

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Definition and Calculation of Hematologic Indices

2.5. Surgical Procedure

2.6. Follow-Up and Outcome Assessment

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

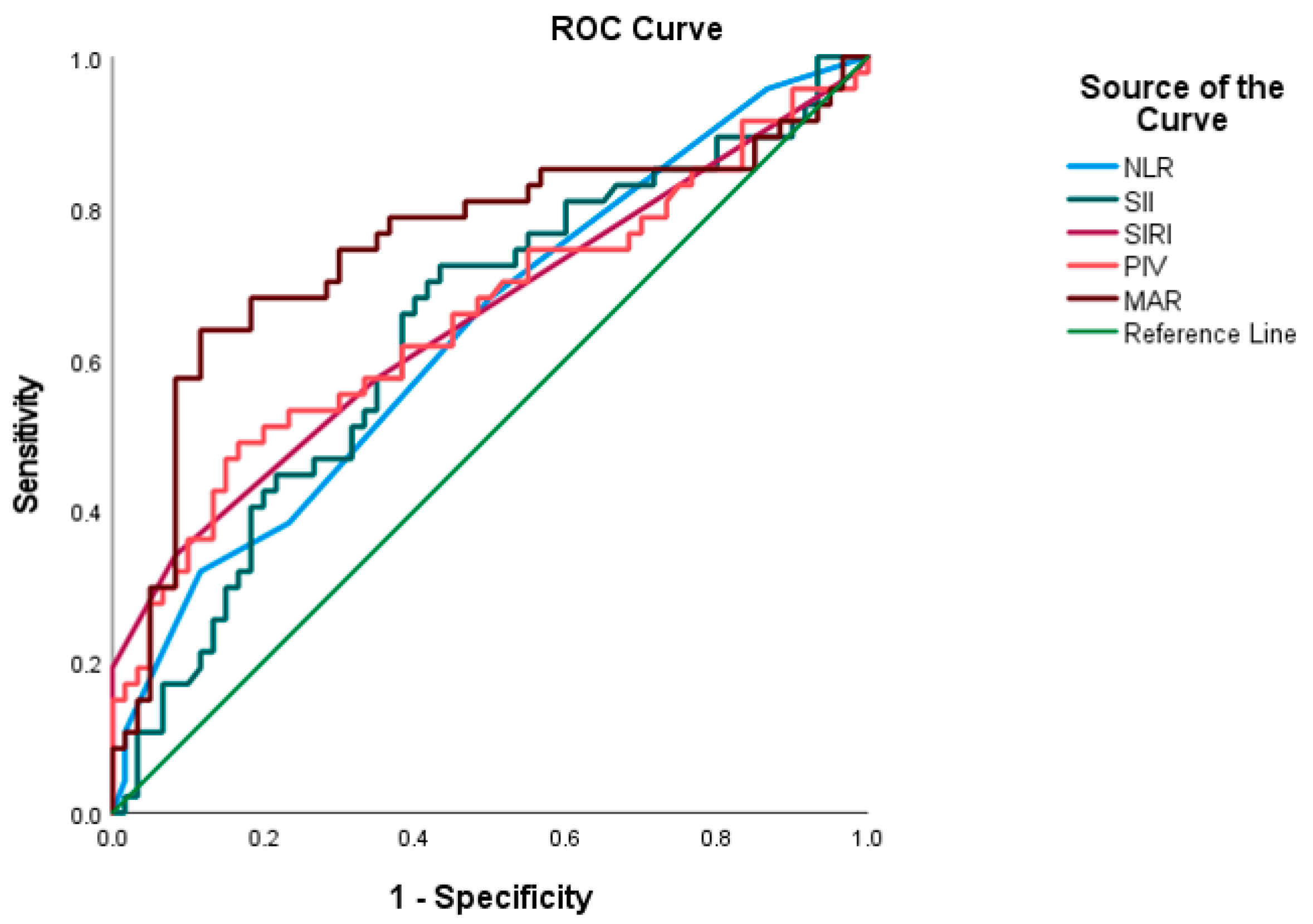

3.2. ROC-Based Predictive Accuracy of Systemic Inflammation–Nutrition Indices

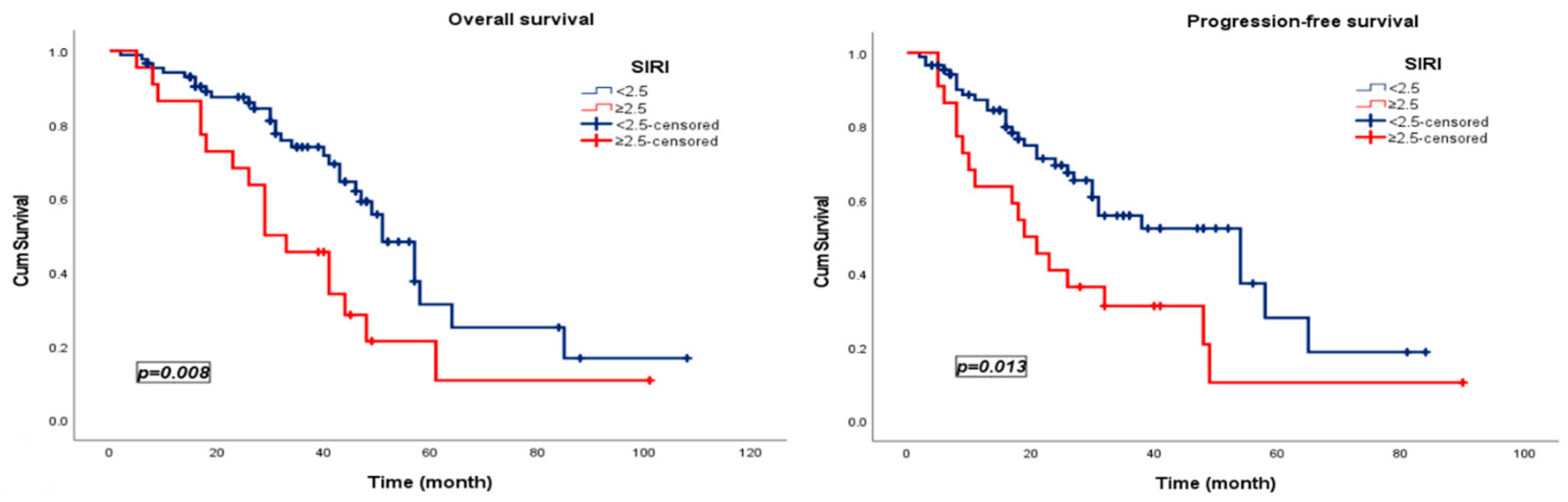

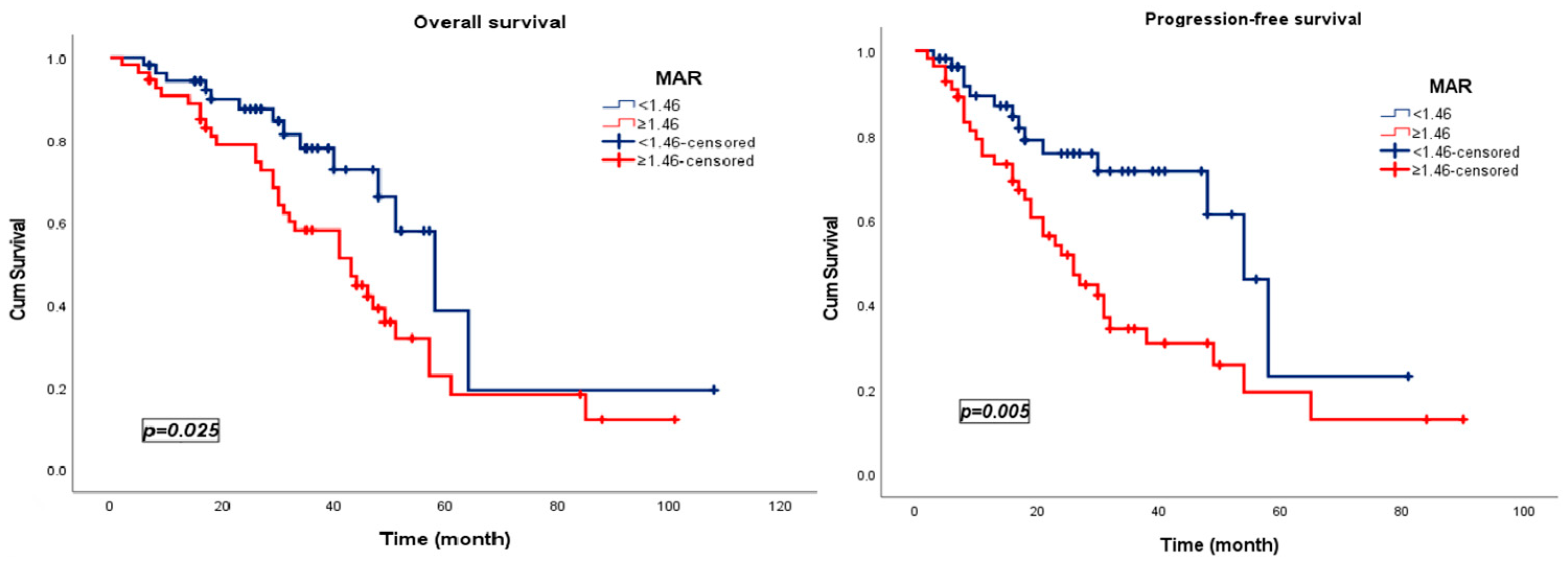

3.3. Survival Analysis

3.4. Univariate and Multivariate Cox Models Evaluating Prognostic Determinants of Survival Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| DFI | Disease-free interval |

| ECOG PS | Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status |

| MAR | Monocyte-to-albumin ratio |

| NLR | Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio |

| OS | Overall survival |

| PET-CT | Positron emission tomography–computed tomography |

| PFS | Progression-free survival |

| PIV | Pan-immune-inflammation value |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic |

| RT | Radiotherapy |

| SII | Systemic immune-inflammation index |

| SIRI | Systemic inflammation response index |

| TAM | Tumor-associated macrophage |

| VATS | Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery |

References

- Gerstberger, S.; Jiang, Q.; Ganesh, K. Metastasis. Cell 2023, 186, 1564–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zullo, L.; Filippiadis, D.; Hendriks, L.E.L.; Portik, D.; Spicer, J.D.; Wistuba, I.I.; Besse, B. Lung Metastases. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2025, 11, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangiameli, G.; Cioffi, U.; Alloisio, M.; Testori, A. Lung Metastases: Current Surgical Indications and New Perspectives. Front. Surg. 2022, 9, 884915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weichselbaum, R.R.; Hellman, S. Oligometastases Revisited. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 8, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katipally, R.R.; Pitroda, S.P.; Weichselbaum, R.R.; Hellman, S. Oligometastases: Characterizing the Role of Epigenetic Regulation of Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 29, 2761–2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handy, J.R.; Bremner, R.M.; Crocenzi, T.S.; Detterbeck, F.C.; Fernando, H.C.; Fidias, P.M.; Firestone, S.; Johnstone, C.A.; Lanuti, M.; Litle, V.R.; et al. Expert Consensus Document on Pulmonary Metastasectomy. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2019, 107, 631–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrella, F.; Diotti, C.; Rimessi, A.; Spaggiari, L. Pulmonary Metastasectomy: An Overview. J. Thorac. Dis. 2017, 9, S1291–S1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poullis, M. Pulmonary Metastasectomy—Back to Basic Biology. Eur. J. Cardio-Thorac. Surg. 2024, 66, ezae272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaftian, N.; Dunne, B.; Antippa, P.N.; Cheung, F.P.; Wright, G.M. Long-term Outcomes of Pulmonary Metastasectomy: A Multicentre Analysis. ANZ J. Surg. 2021, 91, 1260–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seitlinger, J.; Prieto, M.; Siat, J.; Renaud, S. Pulmonary Metastasectomy in Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Mainstay of Multidisciplinary Treatment. J. Thorac. Dis. 2021, 13, 2636–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamenovic, D.; Hohenberger, P.; Roessner, E. Pulmonary Metastasectomy in Soft Tissue Sarcomas: A Systematic Review. J. Thorac. Dis. 2021, 13, 2649–2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberg, M.; Deboever, N.; Antonoff, M.B. Pulmonary Metastasectomy. Thorac. Surg. Clin. 2023, 33, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treasure, T.; Farewell, V.; Macbeth, F.; Monson, K.; Williams, N.R.; Brew-Graves, C.; Lees, B.; Grigg, O.; Fallowfield, L. Pulmonary Metastasectomy versus Continued Active Monitoring in Colorectal Cancer (PulMiCC): A Multicentre Randomised Clinical Trial. Trials 2019, 20, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, W.; Park, B.; Ahadi, A.; Chung, L.I.-Y.; Jung, C.M.; Bharat, A.; Chae, Y.K. The Role of Pulmonary Metastasectomy for Non-Primary Lung Cancer: Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses. J. Surg. Oncol. 2025, 131, 1035–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, A.; Andoh, A. The Role of Inflammation in Cancer: Mechanisms of Tumor Initiation, Progression, and Metastasis. Cells 2025, 14, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, R.; Kanetsky, P.A.; Egan, K.M. Exploring the Prognostic Value of the Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, B.-W.; Yang, Y.-F.; Yang, C.-C.; Yan, L.-J.; Ding, Z.-N.; Liu, H.; Xue, J.-S.; Dong, Z.-R.; Chen, Z.-Q.; Hong, J.-G.; et al. Systemic Immune–Inflammation Index Predicts Prognosis of Cancer Immunotherapy: Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis. Immunotherapy 2022, 14, 1481–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayama, T.; Ochiai, H.; Ozawa, T.; Miyata, T.; Asako, K.; Fukushima, Y.; Kaneko, K.; Nozawa, K.; Fujii, S.; Misawa, T.; et al. High Systemic Inflammation Response Index (SIRI) Level as a Prognostic Factor for Colorectal Cancer Patients after Curative Surgery: A Single-Center Retrospective Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, A.A.; Kayikcioglu, E.; Unlu, A.; Acun, M.; Guzel, H.G.; Yavuz, R.; Ozgul, H.; Onder, A.H.; Ozturk, B.; Yildiz, M. Pan-Immune-Inflammation Value as a Novel Prognostic Biomarker for Advanced Pancreatic Cancer. Cureus 2024, 16, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.-T.; Chen, X.-X.; Yang, X.-M.; He, S.-C.; Qian, F.-H. Application of Monocyte-to-Albumin Ratio and Neutrophil Percentage-to-Hemoglobin Ratio on Distinguishing Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients from Healthy Subjects. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2023, 16, 2175–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibutani, M.; Maeda, K.; Nagahara, H.; Fukuoka, T.; Nakao, S.; Matsutani, S.; Hirakawa, K.; Ohira, M. The Peripheral Monocyte Count Is Associated with the Density of Tumor-Associated Macrophages in the Tumor Microenvironment of Colorectal Cancer: A Retrospective Study. BMC Cancer 2017, 17, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Song, Y.; Du, W.; Gong, L.; Chang, H.; Zou, Z. Tumor-Associated Macrophages: An Accomplice in Solid Tumor Progression. J. Biomed. Sci. 2019, 26, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.; Yi, M.; Wu, Y.; Dong, B.; Wu, K. Roles of Tumor-Associated Macrophages in Tumor Progression: Implications on Therapeutic Strategies. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 10, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aras, S.; Zaidi, M.R. TAMeless Traitors: Macrophages in Cancer Progression and Metastasis. Br. J. Cancer 2017, 117, 1583–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, P.J. Immune Regulation by Monocytes. Semin. Immunol. 2018, 35, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yung, M.M.H.; Ngan, H.Y.S.; Chan, K.K.L.; Chan, D.W. The Impact of the Tumor Microenvironment on Macrophage Polarization in Cancer Metastatic Progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Li, J.; Lai, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Su, J.; Che, G. Perioperative Changes of Serum Albumin Are a Predictor of Postoperative Pulmonary Complications in Lung Cancer Patients: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Thorac. Dis. 2018, 10, 5755–5763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanim, B.; Schweiger, T.; Jedamzik, J.; Glueck, O.; Glogner, C.; Lang, G.; Klepetko, W.; Hoetzenecker, K. Elevated Inflammatory Parameters and Inflammation Scores Are Associated with Poor Prognosis in Patients Undergoing Pulmonary Metastasectomy for Colorectal Cancer. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2015, 21, 616–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renaud, S.; Seitlinger, J.; St-Pierre, D.; Garfinkle, R.; Al Lawati, Y.; Guerrera, F.; Ruffini, E.; Falcoz, P.-E.; Massard, G.; Ferri, L.; et al. Prognostic Value of Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio in Lung Metastasectomy for Colorectal Cancer. Eur. J. Cardio-Thorac. Surg. 2019, 55, 948–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Londero, F.; Grossi, W.; Parise, O.; Cinel, J.; Parise, G.; Masullo, G.; Tetta, C.; Micali, L.R.; Mauro, E.; Morelli, A.; et al. The Impact of Preoperative Inflammatory Markers on the Prognosis of Patients Undergoing Surgical Resection of Pulmonary Oligometastases. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable, n (%) | SIRI, n (%) | MAR, n (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (<2.5) † | High (≥2.5) † | p | Low (<1.46) † | High (≥1.46) † | p | |||

| Age | <65 | 68 (62.4) | 56 (64.4) | 12 (54.5) | 0.271 | 39 (70.9) | 29 (53.7) | 0.046 |

| ≥65 | 41 (37.6) | 31 (35.6) | 10 (45.5) | 16 (29.1) | 25 (46.3) | |||

| Sex | Female | 53 (48.6) | 43 (49.4) | 10 (45.5) | 0.463 | 33 (60.0) | 20 (37.0) | 0.013 |

| Male | 56 (51.4) | 44 (50.6) | 12 (54.5) | 22 (40.0) | 34 (63.0) | |||

| Smoking | No | 68 (62.4) | 53 (60.9) | 15 (68.2) | 0.356 | 31 (56.4) | 37 (68.5) | 0.133 |

| Yes | 41 (37.6) | 34 (39.1) | 7 (31.8) | 24 (43.6) | 17 (31.5) | |||

| Comorbidity | No | 54 (49.5) | 44 (50.6) | 10 (45.5) | 0.425 | 31 (56.4) | 23 (42.6) | 0.106 |

| Yes | 55 (50.5) | 43 (49.4) | 12 (54.5) | 24 (43.6) | 31 (57.4) | |||

| ECOG PS | 0–1 | 62 (56.9) | 52 (59.8) | 10 (45.5) | 0.166 | 32 (58.2) | 30 (55.6) | 0.467 |

| ≥2 | 47 (43.1) | 35 (40.2) | 12 (54.5) | 23 (41.8) | 24 (44.4) | |||

| Primary tumor origin | Breast | 20 (18.3) | 18 (20.7) | 2 (9.1) | 0.439 | 11 (20.0) | 9 (16.7) | 0.487 |

| Gastrointestinal | 56 (51.4) | 44 (50.6) | 12 (54.5) | 27 (49.1) | 29 (53.7) | |||

| Gynecologic | 13 (11.9) | 9 (10.3) | 4 (18.2) | 10 (18.2) | 3 (5.6) | |||

| Genitourinary | 11 (10.1) | 8 (9.2) | 3 (13.6) | 3 (5.5) | 8 (14.8) | |||

| Others | 9 (8.3) | 8 (9.2) | 1 (4.5) | 4 (7.3) | 5 (9.3) | |||

| Tumor localization | Left upper | 32 (29.4) | 22 (25.3) | 10 (45.5) | 0.894 | 16 (29.1) | 16 (29.6) | 0.665 |

| Right upper | 28 (25.7) | 26 (29.9) | 2 (9.1) | 13 (23.6) | 15 (27.8) | |||

| Left lower | 23 (21.1) | 20 (23.0) | 3 (13.6) | 12 (21.8) | 11 (20.4) | |||

| Right lower | 21 (19.3) | 16 (18.4) | 5 (22.7) | 11 (20.0) | 10 (18.5) | |||

| Middle | 5 (4.6) | 3 (3.4) | 2 (9.1) | 3 (5.5) | 2 (3.7) | |||

| Tumor size | <1 cm | 19 (17.4) | 18 (20.7) | 1 (4.5) | 0.062 | 13 (23.6) | 6 (11.1) | 0.070 |

| ≥1 cm | 90 (82.6) | 69 (79.3) | 21 (95.5) | 42 (76.4) | 48 (88.9) | |||

| Surgical procedure | VATS | 91 (83.5) | 72 (82.8) | 19 (86.4) | 0.484 | 46 (83.6) | 45 (83.3) | 0.186 |

| Thoracotomy | 18 (16.5) | 15 (17.2) | 3 (13.6) | 9 (16.4) | 9 (16.7) | |||

| Resection type | Wedge | 85 (78.0) | 66 (78.6) | 19 (86.4) | 0.313 | 41 (74.5) | 44 (86.3) | 0.102 |

| Segmentectomy /Lobectomy | 24 (22.0) | 18 (21.4) | 3 (13.6) | 14 (25.5) | 7 (13.7) | |||

| Adjuvant chemo | No | 23 (21.1) | 18 (20.7) | 5 (22.7) | 0.519 | 9 (16.4) | 14 (25.9) | 0.161 |

| Yes | 86 (78.9) | 69 (79.3) | 17 (77.3) | 46 (83.6) | 40 (74.1) | |||

| Adjuvant RT | No | 69 (63.3) | 56 (64.4) | 13 (59.1) | 0.412 | 34 (61.8) | 35 (64.8) | 0.450 |

| Yes | 40 (36.7) | 31 (35.6) | 9 (40.9) | 21 (38.2) | 19 (35.2) | |||

| Lymph node involvement | No | 81 (74.3) | 66 (75.9) | 15 (68.2) | 0.314 | 41 (74.5) | 40 (74.1) | 0.564 |

| Yes | 28 (25.7) | 21 (24.1) | 7 (31.8) | 14 (25.5) | 14 (25.9) | |||

| Number of pulmonary metastases | Solitary | 72 (66.1) | 59 (67.8) | 13 (59.1) | 0.298 | 40 (72.7) | 32 (59.3) | 0.100 |

| Multiple | 37 (33.9) | 28 (32.2) | 9 (40.9) | 15 (27.3) | 22 (40.7) | |||

| Postoperative complications | No | 102 (93.6) | 82 (94.3) | 20 (90.9) | 0.431 | 53 (96.4) | 49 (90.7) | 0.211 |

| Yes | 7 (6.4) | 5 (5.7) | 2 (9.1) | 2 (3.6) | 5 (9.3) | |||

| NLR, (4.5) † | Low | 22 (20.2) | 8 (9.2) | 14 (63.6) | <0.001 | 10 (18.2) | 12 (22.2) | 0.387 |

| High | 87 (79.8) | 79 (90.8) | 8 (36.4) | 45 (81.8) | 42 (77.8) | |||

| SII, (446.5) † | Low | 25 (22.9) | 25 (28.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.002 | 13 (23.6) | 12 (22.2) | 0.521 |

| High | 84 (77.1) | 62 (71.3) | 22 (100.0) | 42 (76.4) | 42 (77.8) | |||

| PIV, (209.5) † | Low | 21 (19.3) | 21 (24.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.005 | 13 (23.6) | 8 (14.8) | 0.178 |

| High | 88 (70.7) | 66 (75.9) | 22 (100.0) | 42 (76.4) | 46 (85.2) | |||

| Marker | AUC | Std. Error | p | 95% CI | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Cut-Off | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||||

| NLR | 0.635 | 0.054 | 0.017 | 0.529 | 0.741 | 69.1 | 88.3 | 4.5 |

| SII | 0.637 | 0.054 | 0.015 | 0.530 | 0.744 | 66.0 | 91.7 | 446.5 |

| SIRI | 0.682 | 0.055 | 0.007 | 0.545 | 0.760 | 85.1 | 72.7 | 2.5 |

| PIV | 0.655 | 0.055 | 0.006 | 0.547 | 0.763 | 85.1 | 76.7 | 209.5 |

| MAR | 0.749 | 0.052 | <0.001 | 0.647 | 0.850 | 74.5 | 68.3 | 1.46 |

| Overall Survival | Exp(B) | 95.0% CI for Exp(B) | p | Progression-Free Survival | Exp(B) | 95.0% CI for Exp(B) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Age | 1.085 | 0.611 | 1.924 | 0.781 | Age | 1.082 | 0.606 | 1.930 | 0.790 |

| Sex | 0.878 | 0.487 | 1.581 | 0.664 | Sex | 0.980 | 0.552 | 1.742 | 0.946 |

| Surgical procedure | 0.579 | 0.259 | 1.294 | 0.183 | Surgical procedure | 0.570 | 0.255 | 1.273 | 0.170 |

| Type of resection | 0.433 | 0.170 | 1.100 | 0.078 | Type of resection | 0.417 | 0.164 | 1.058 | 0.066 |

| ECOG PS | 1.136 | 0.646 | 1.998 | 0.657 | ECOG PS | 1.105 | 0.629 | 1.942 | 0.729 |

| Smoking status | 1.290 | 0.725 | 2.295 | 0.387 | Smoking status | 1.169 | 0.660 | 2.072 | 0.592 |

| Comorbidity | 1.682 | 0.940 | 3.008 | 0.080 | Comorbidity | 1.543 | 0.859 | 2.773 | 0.146 |

| Adjuvant chemo | 1.106 | 0.516 | 2.368 | 0.796 | Adjuvant chemo | 1.293 | 0.604 | 2.769 | 0.508 |

| Adjuvant RT | 1.429 | 0.805 | 2.535 | 0.223 | Adjuvant RT | 1.501 | 0.847 | 2.660 | 0.164 |

| Primary tumor origin | 0.956 | 0.772 | 1.183 | 0.679 | Primary tumor origin | 0.953 | 0.770 | 1.179 | 0.659 |

| Tumor diameter | 1.411 | 0.597 | 3.331 | 0.433 | Tumor diameter | 1.823 | 0.769 | 4.321 | 0.173 |

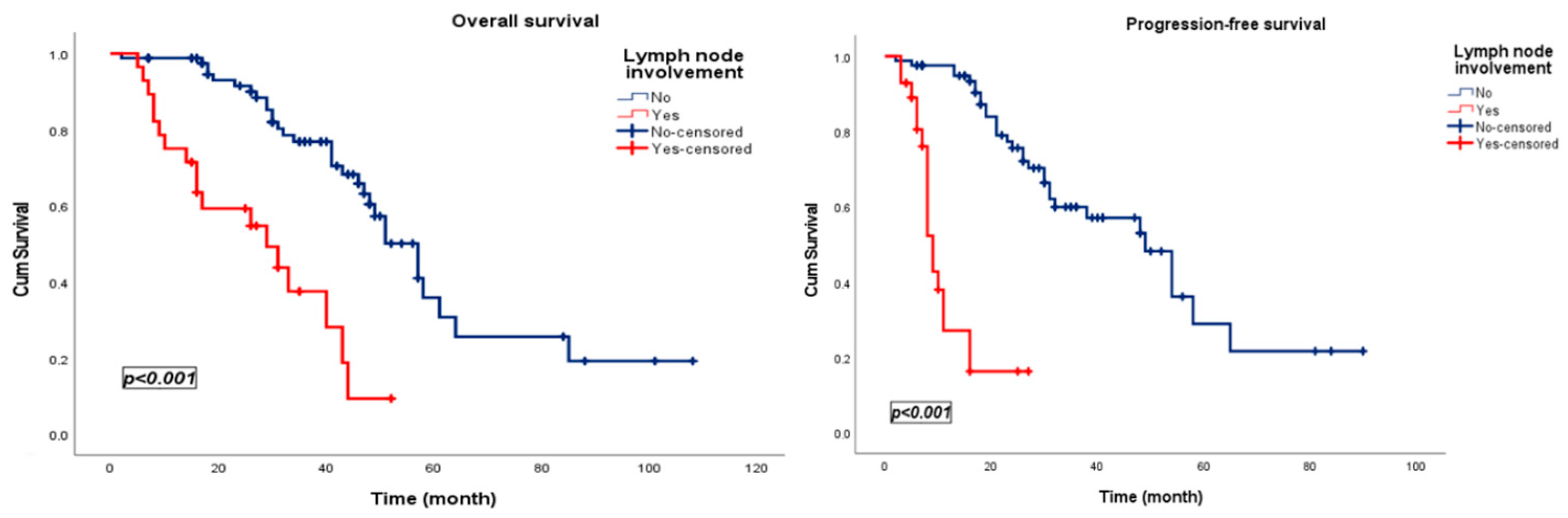

| Lymph node involvement | 4.438 | 2.360 | 8.344 | <0.001 | Lymph node involvement | 10.101 | 4.975 | 20.510 | <0.001 |

| Tumor localization | 1.032 | 0.827 | 1.287 | 0.782 | Tumor localization | 1.093 | 0.868 | 1.377 | 0.449 |

| Metastatic site | 1.653 | 0.935 | 2.921 | 0.084 | Metastatic site | 2.001 | 1.131 | 3.542 | 0.017 |

| Postoperative complication | 1.770 | 0.696 | 4.501 | 0.231 | Postoperative complication | 1.765 | 0.688 | 4.526 | 0.237 |

| NLR | 1.291 | 0.691 | 2.413 | 0.423 | NLR | 1.309 | 0.702 | 2.438 | 0.397 |

| SII | 1.240 | 0.579 | 2.654 | 0.580 | SII | 1.428 | 0.667 | 3.060 | 0.359 |

| SIRI | 2.180 | 1.208 | 3.936 | 0.010 | SIRI | 2.067 | 1.147 | 3.727 | 0.016 |

| PIV | 1.311 | 0.586 | 2.931 | 0.510 | PIV | 1.388 | 0.623 | 3.093 | 0.423 |

| MAR | 2.128 | 1.118 | 4.049 | 0.021 | MAR | 2.445 | 1.289 | 4.638 | 0.006 |

| Overall Survival | Exp(B) | 95.0% CI for Exp(B) | p | Progression-Free Survival | Exp(B) | 95.0% CI for Exp(B) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Lymph node involvement | 4.526 | 2.340 | 8.751 | <0.001 | Lymph node involvement | 14.124 | 6.089 | 32.761 | <0.001 |

| - | - | - | - | - | Metastatic site | 2.019 | 1.095 | 3.720 | 0.024 |

| SIRI | 1.731 | 0.927 | 3.234 | 0.085 | SIRI | 1.893 | 1.021 | 3.509 | 0.043 |

| MAR | 2.002 | 1.022 | 3.920 | 0.043 | MAR | 2.189 | 1.114 | 4.303 | 0.023 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yesilcay, H.B.; Aydin, A.A.; Unlu, A.; Akdag, S.; Yuceer, K.; Yildiz, M. Monocyte-Driven Systemic Biomarkers and Survival After Pulmonary Metastasectomy in Metachronous Lung-Limited Oligometastatic Disease: A Retrospective Single-Center Study. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 476. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020476

Yesilcay HB, Aydin AA, Unlu A, Akdag S, Yuceer K, Yildiz M. Monocyte-Driven Systemic Biomarkers and Survival After Pulmonary Metastasectomy in Metachronous Lung-Limited Oligometastatic Disease: A Retrospective Single-Center Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(2):476. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020476

Chicago/Turabian StyleYesilcay, Hacer Boztepe, Asim Armagan Aydin, Ahmet Unlu, Sencan Akdag, Kamuran Yuceer, and Mustafa Yildiz. 2026. "Monocyte-Driven Systemic Biomarkers and Survival After Pulmonary Metastasectomy in Metachronous Lung-Limited Oligometastatic Disease: A Retrospective Single-Center Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 2: 476. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020476

APA StyleYesilcay, H. B., Aydin, A. A., Unlu, A., Akdag, S., Yuceer, K., & Yildiz, M. (2026). Monocyte-Driven Systemic Biomarkers and Survival After Pulmonary Metastasectomy in Metachronous Lung-Limited Oligometastatic Disease: A Retrospective Single-Center Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(2), 476. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020476