Persistent Liver Manifestations in Allopurinol-Induced Sweet’s Syndrome: An Uncommon Case Report

Abstract

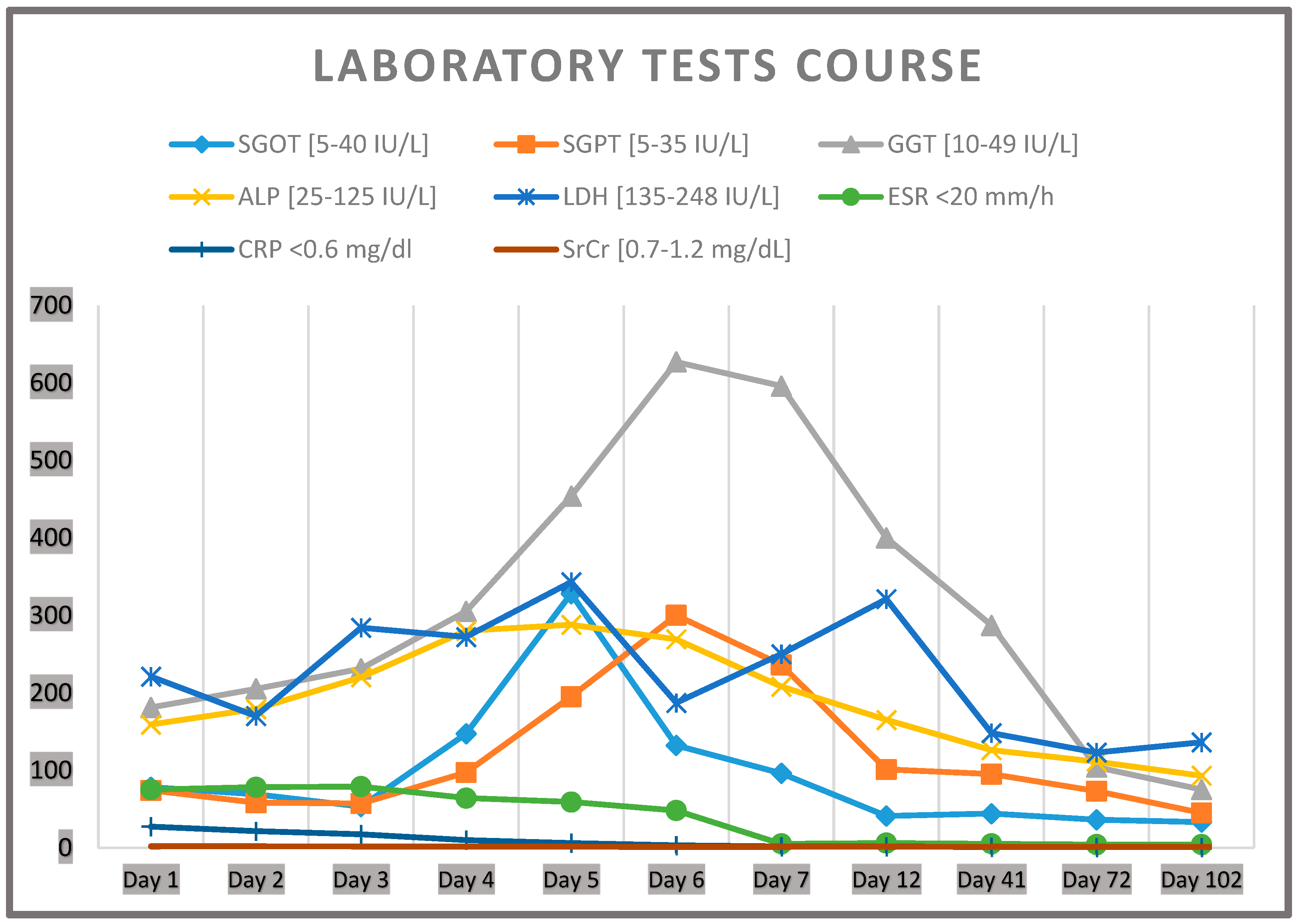

1. Introduction

2. Case Presentation

2.1. Case Description

2.2. Diagnostic Assessment

3. Discussion

4. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SS | Sweet’s syndrome |

| IL-1 | Interleukin-1 |

| G-CSF | Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor |

| DISS | Drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome |

| SGOT | Serum glutamic–oxaloacetic transaminase |

| SGPT | Serum glutamate–pyruvate transaminase |

| GGT | Gamma-glutamyltransferase |

| ALP | Alkaline phosphatase |

| LDH | Lactate dehydrogenase |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| SrCr | Serum creatinine |

| ESR | Erythrocyte sedimentation rate |

| BID | Twice daily |

| SJS | Stevens–Johnson syndrome |

| EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors |

| DRESS | Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms |

| G-MCSF | Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor |

| INF-γ | Interferon-γ |

References

- Cohen, P.R. Sweet’s syndrome—A comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2007, 2, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, T.P.; Friske, S.K.; Hsiou, D.A.; Duvic, M. New Practical Aspects of Sweet Syndrome. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2022, 23, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villarreal-Villarreal, C.D.; Ocampo-Candiani, J.; Villarreal-Martínez, A. Sweet Syndrome: A Review and Update. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016, 107, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heath, M.S.; Ortega-Loayza, A.G. Insights Into the Pathogenesis of Sweet’s Syndrome. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Ying, S.; Wang, Y.; Lv, Y.; Qiao, J.; Fang, H. Neutrophil extracellular traps and neutrophilic dermatosis: An update review. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, D.F.; Montarella, K.E. Drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome. Ann. Pharmacother. 2007, 41, 802–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polimeni, G.; Cardillo, R.; Garaffo, E.; Giardina, C.; Macrì, R.; Sirna, V.; Guarneri, C.; Arcoraci, V. Allopurinol-induced Sweet’s syndrome. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2016, 29, 329–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, C.W.; Kim, Y.J.; Seo, H.J.; Lee, K.I.; Jang, B.K.; Hwang, J.S.; Chung, W.J. A case of Sweet’s syndrome in a patient with liver cirrhosis caused by chronic hepatitis B. Korean J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 59, 441–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cinats, A.K.; Haber, R.M. Case Report of Sweet’s Syndrome Associated with Autoimmune Hepatitis. J. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2017, 21, 72–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, D.; Parsons, L.M. Sweet syndrome in a patient with chronic hepatitis C. J. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2014, 18, 436–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, C.M.; Li, J.J.; Ip, E.C.; Chan, A.W. Sweet syndrome induced by epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors. Indian. J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2022, 88, 664–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naranjo, C.A.; Busto, U.; Sellers, E.M.; Sandor, P.; Ruiz, I.; Roberts, E.A.; Janecek, E.; Domecq, C.; Greenblatt, D.J. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1981, 30, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagugli, R.M.; Gentile, G.; Ferrara, G.; Brugnano, R. Acute renal and hepatic failure associated with allopurinol treatment. Clin. Nephrol. 2008, 70, 523–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamp, L.K.; Barclay, M.L. How to prevent allopurinol hypersensitivity reactions? Rheumatology 2018, 57, i35–i41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Zhao, S.; Chen, W. Clinical features, treatment outcomes and prognostic factors of allopurinol-induced DRESS in 52 patients. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2022, 47, 1368–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akovbyan, V.; Talanin, N.; Tukhvatullina, Z. Sweet’s syndrome in patients with kidney and liver disorders. Cutis 1992, 49, 448–450. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Philips, C.A.; Paramaguru, R.; Augustine, P. Strange case of dimorphic skin rash in a patient with cirrhosis: Atypical herpes simplex and sweet’s syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2017, 2017, bcr2017220743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, M.G.; Hastings, A. Sweet’s syndrome progressing to pyoderma gangrenosum--a spectrum of neutrophilic skin disease in association with cryptogenic cirrhosis. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 1991, 16, 279–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinojima, Y.; Toma, Y.; Terui, T. Sweet syndrome associated with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma producing granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Br. J. Dermatol. 2006, 155, 1103–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Helwig, K.; Komar, M.J. Sweet’s syndrome in association with probable autoimmune hepatitis. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 1999, 29, 349–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Papanikolopoulou, A.; Siasiakou, S.M.; Pantazopoulos, K.; Trontzas, I.P.; Fyta, E.; Fiste, O.; Syrigou, E.; Syrigos, N. Persistent Liver Manifestations in Allopurinol-Induced Sweet’s Syndrome: An Uncommon Case Report. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7186. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207186

Papanikolopoulou A, Siasiakou SM, Pantazopoulos K, Trontzas IP, Fyta E, Fiste O, Syrigou E, Syrigos N. Persistent Liver Manifestations in Allopurinol-Induced Sweet’s Syndrome: An Uncommon Case Report. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(20):7186. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207186

Chicago/Turabian StylePapanikolopoulou, Amalia, Sofia M. Siasiakou, Kosmas Pantazopoulos, Ioannis P Trontzas, Eleni Fyta, Oraianthi Fiste, Ekaterini Syrigou, and Nikolaos Syrigos. 2025. "Persistent Liver Manifestations in Allopurinol-Induced Sweet’s Syndrome: An Uncommon Case Report" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 20: 7186. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207186

APA StylePapanikolopoulou, A., Siasiakou, S. M., Pantazopoulos, K., Trontzas, I. P., Fyta, E., Fiste, O., Syrigou, E., & Syrigos, N. (2025). Persistent Liver Manifestations in Allopurinol-Induced Sweet’s Syndrome: An Uncommon Case Report. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(20), 7186. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207186