Real-World Survival Outcomes Following Metastasectomy in RAS Wild-Type mCRC: Insights from a Multicentre National Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods and Materials

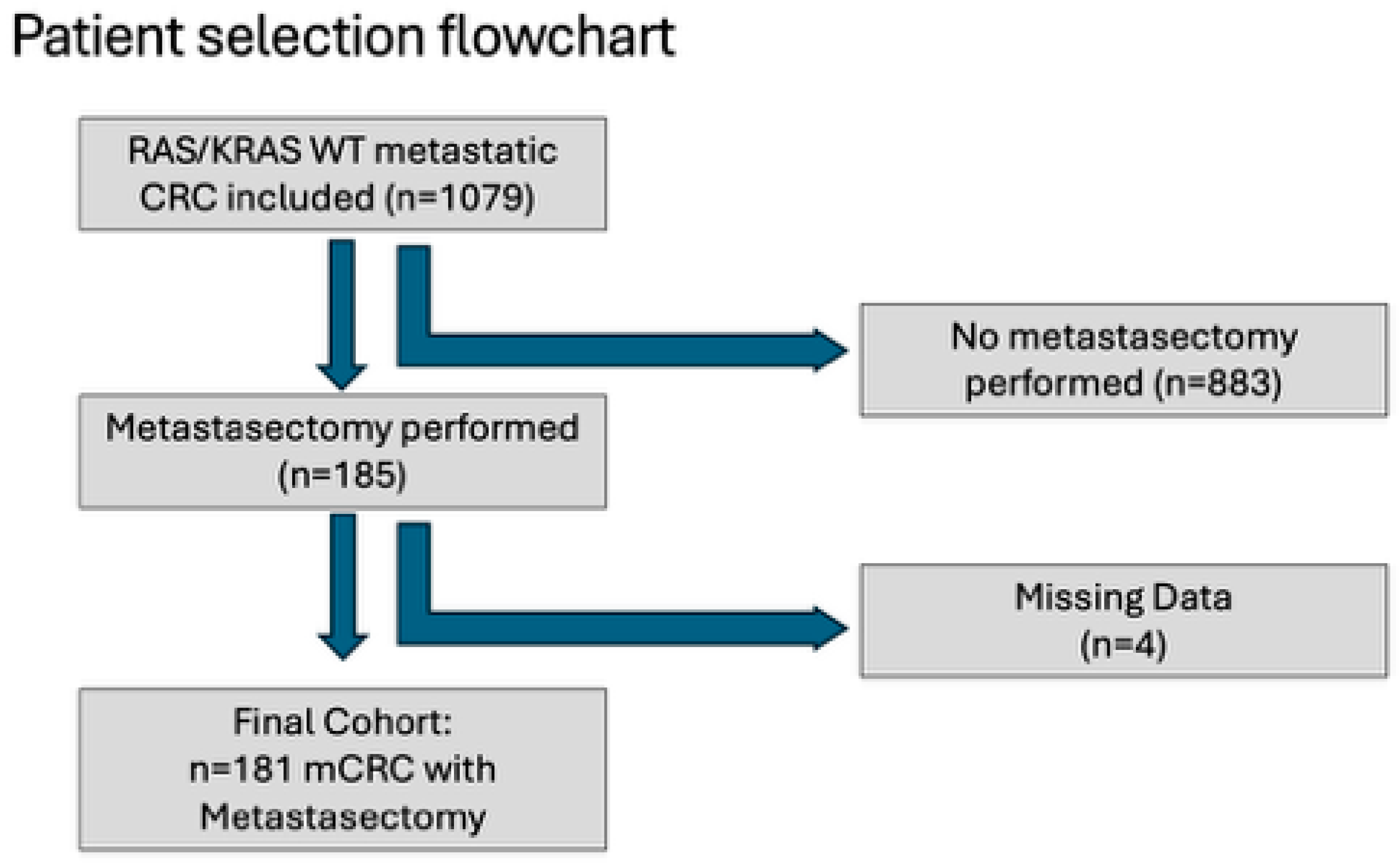

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Data Collection and Variables

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Metastasectomy Cohort Characteristics

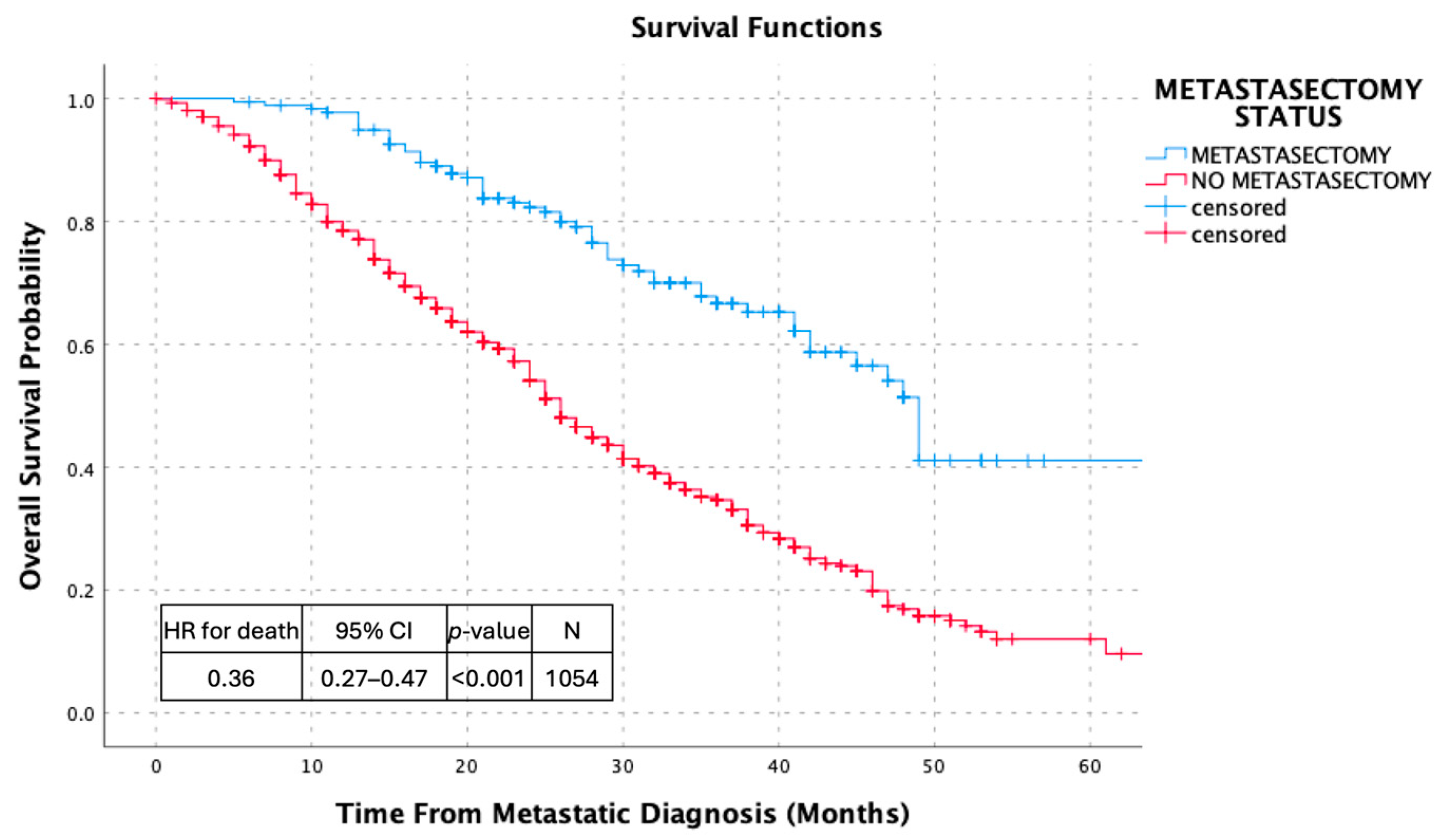

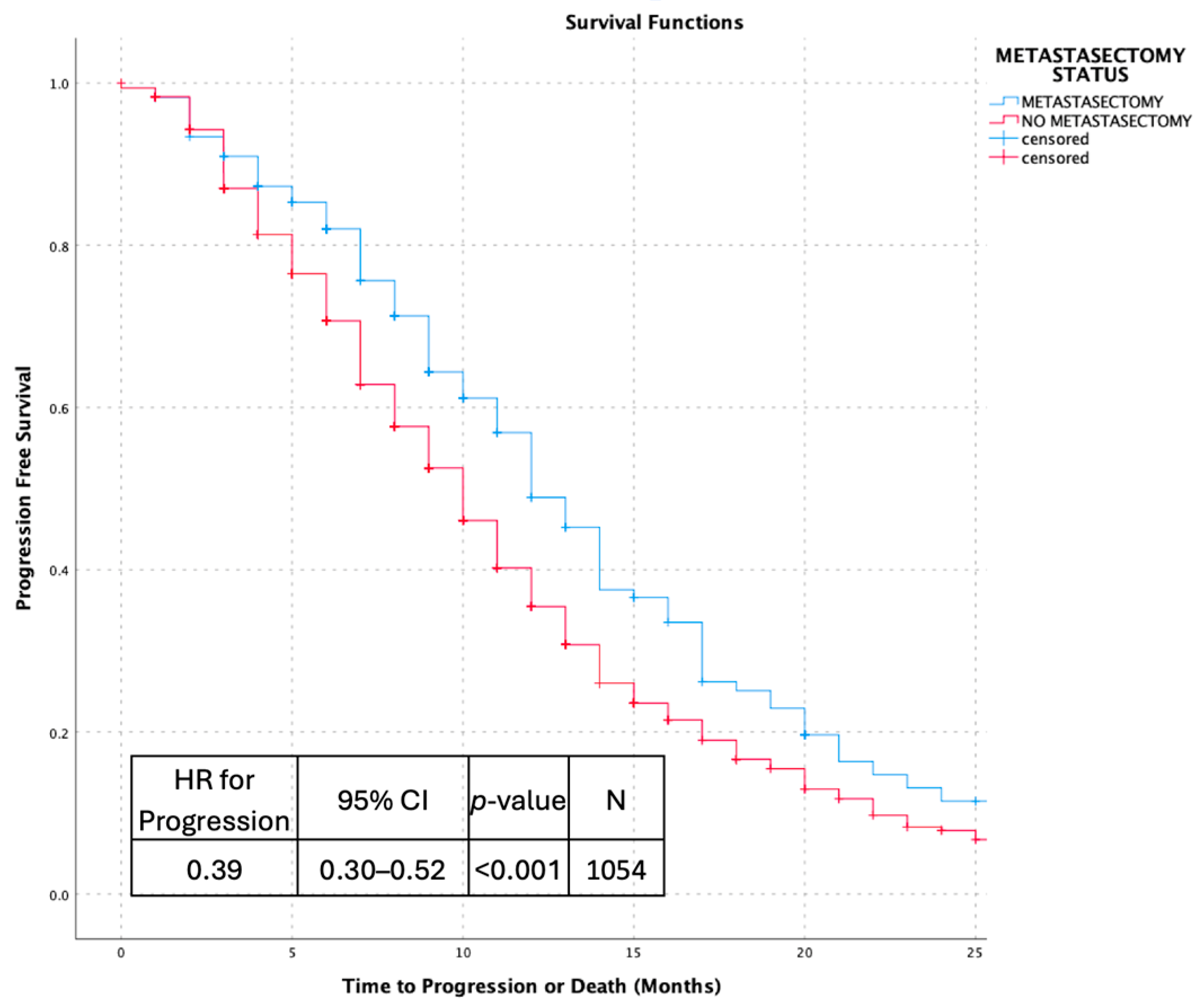

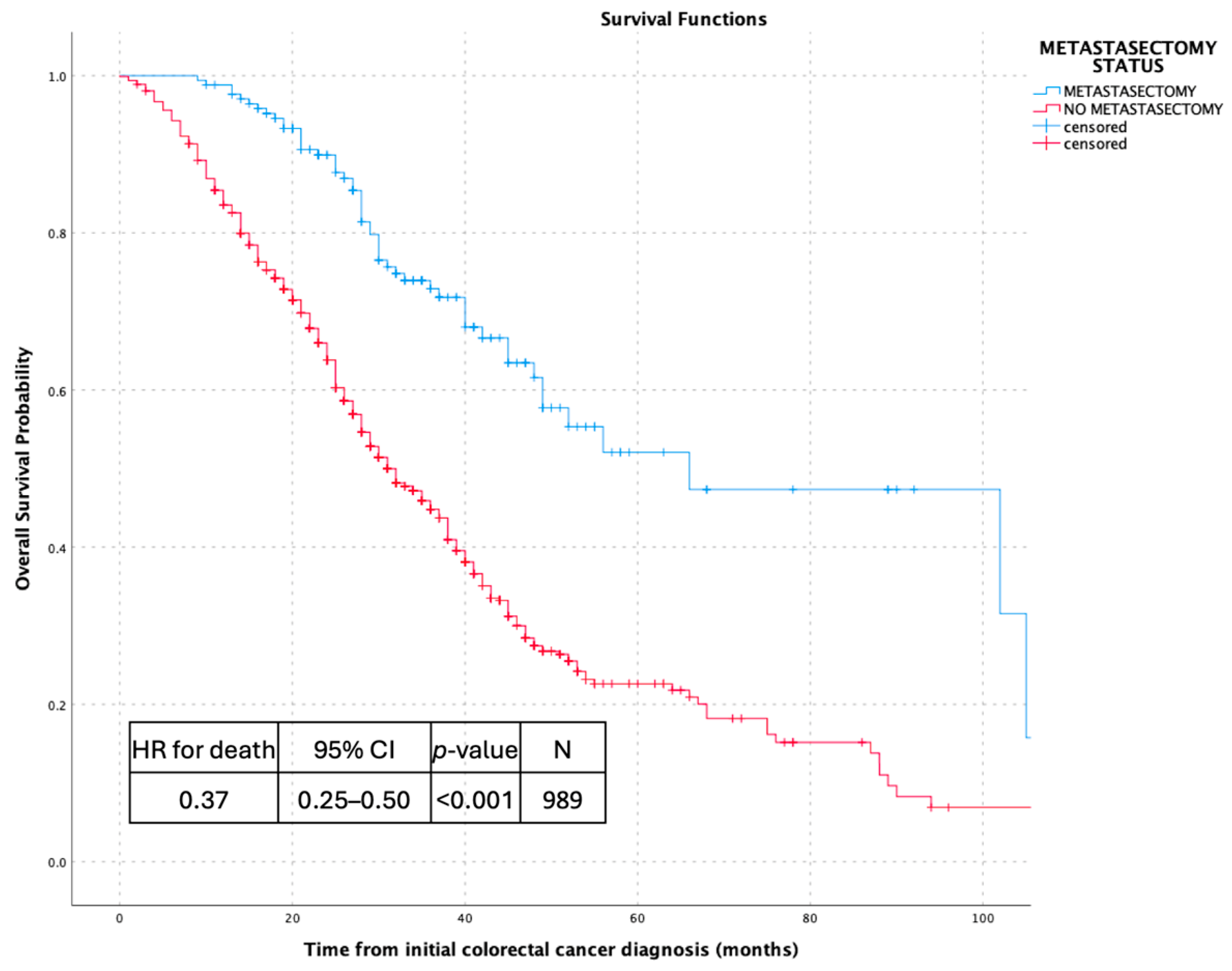

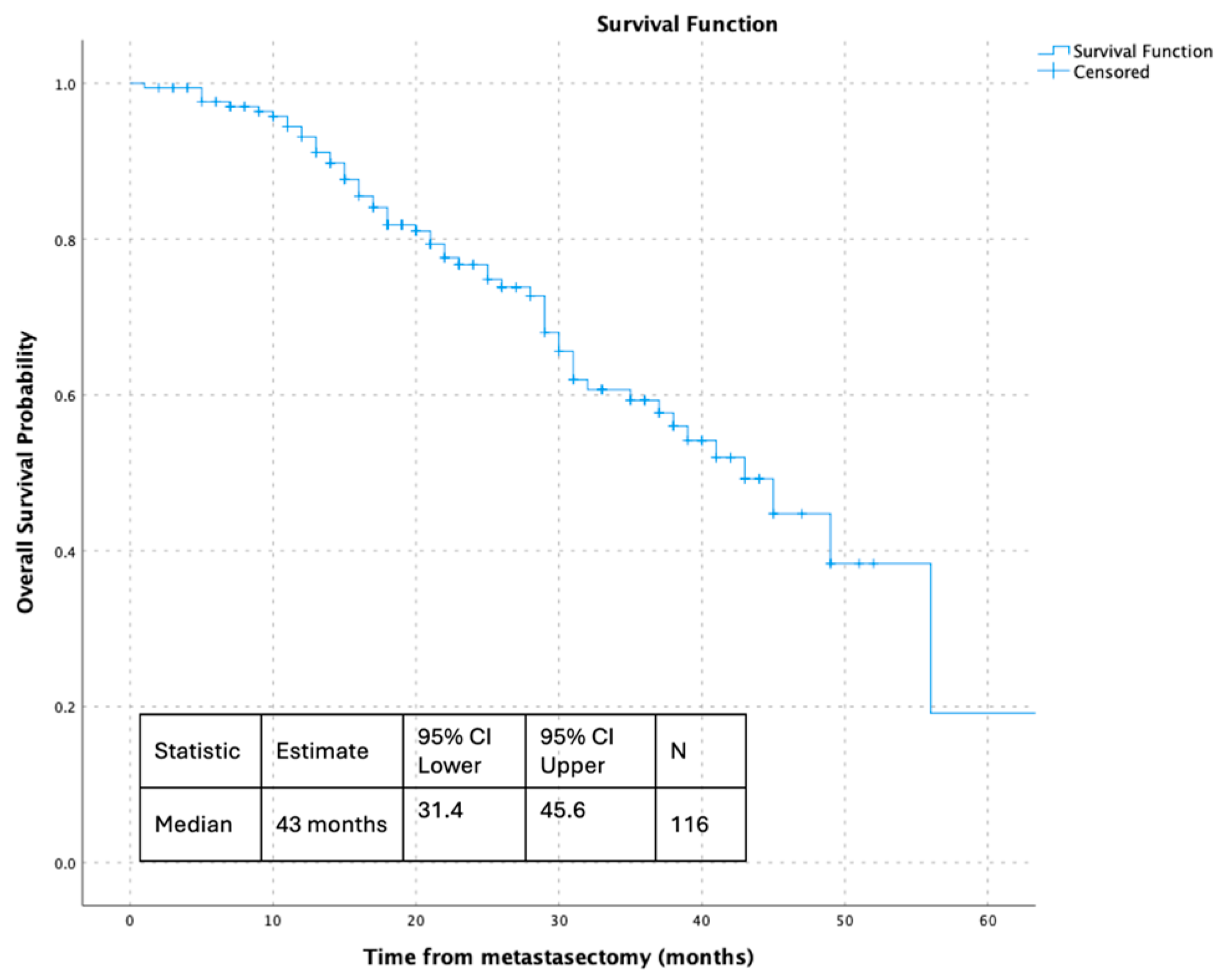

3.2. Survival Outcomes

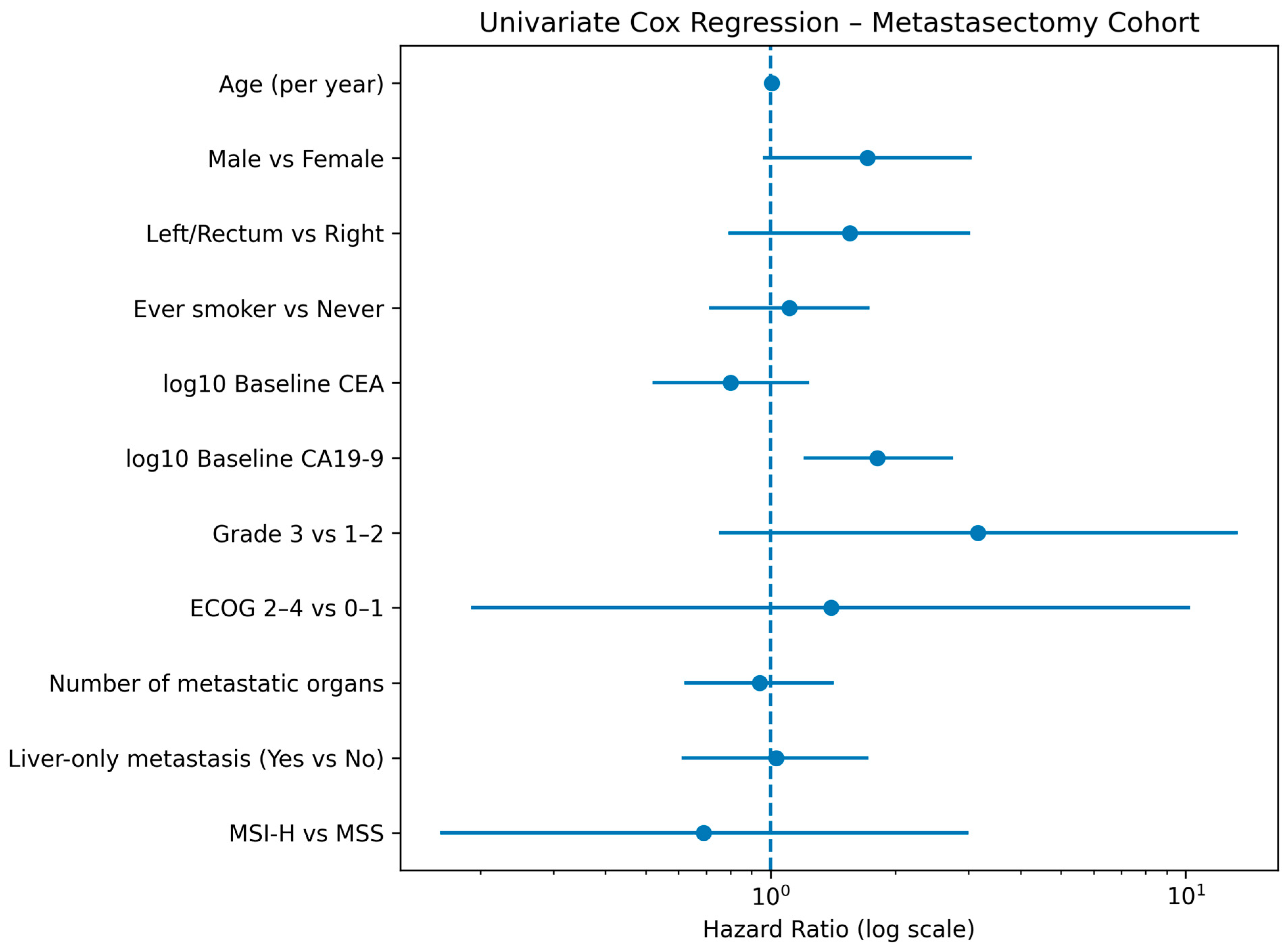

3.3. Univariate Analysis

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tsilimigras, D.I.; Ntanasis-Stathopoulos, I.; Pawlik, T.M. Molecular Mechanisms of Colorectal Liver Metastases. Cells 2023, 12, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordlinger, B.; Sorbye, H.; Glimelius, B.; Poston, G.J.; Schlag, P.M.; Rougier, P.; Bechstein, W.O.; Primrose, J.N.; Walpole, E.T.; Finch-Jones, M.; et al. Perioperative chemotherapy with FOLFOX4 and surgery versus surgery alone for resectable liver metastases from colorectal cancer (EORTC Intergroup trial 40983): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2008, 371, 1007–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdalla, E.K.; Vauthey, J.N.; Ellis, L.M.; Ellis, V.; Pollock, R.; Broglio, K.R.; Hess, K.; Curley, S.A. Recurrence and Outcomes Following Hepatic Resection, Radiofrequency Ablation, and Combined Resection/Ablation for Colorectal Liver Metastases. Ann. Surg. 2004, 239, 818–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, M.G.; Ito, H.; Gönen, M.; Fong, Y.; Allen, P.J.; DeMatteo, R.P.; Brennan, M.F.; Blumgart, L.H.; Jarnagin, W.R.; D’Angelica, M.I. Survival after Hepatic Resection for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: Trends in Outcomes for 1,600 Patients during Two Decades at a Single Institution. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2010, 210, 744–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Germani, M.M.; Borelli, B.; Boraschi, P.; Antoniotti, C.; Ugolini, C.; Urbani, L.; Morelli, L.; Fontanini, G.; Masi, G.; Cremolini, C.; et al. The management of colorectal liver metastases amenable of surgical resection: How to shape treatment strategies according to clinical, radiological, pathological and molecular features. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2022, 106, 102382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, R.; Wicherts, D.A.; De Haas, R.J.; Ciacio, O.; Lévi, F.; Paule, B.; Ducreux, M.; Azoulay, D.; Bismuth, H.; Castaing, D. Patients with Initially Unresectable Colorectal Liver Metastases: Is There a Possibility of Cure? J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 1829–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folprecht, G.; Gruenberger, T.; Bechstein, W.O.; Raab, H.R.; Lordick, F.; Hartmann, J.T.; Lang, H.; Frilling, A.; Stoehlmacher, J.; Weitz, J.; et al. Tumour response and secondary resectability of colorectal liver metastases following neoadjuvant chemotherapy with cetuximab: The CELIM randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010, 11, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrabaszcz, S.; Rajeev, R.; Witmer, H.D.D.; Dhiman, A.; Klooster, B.; Gamblin, T.C.; Banerjee, A.; Johnston, F.M.M.; Turaga, K.K. A Systematic Review of Conversion to Resectability in Unresectable Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Chemotherapy Trials. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 45, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, D.; Humblet, Y.; Siena, S.; Khayat, D.; Bleiberg, H.; Santoro, A.; Bets, D.; Mueser, M.; Harstrick, A.; Verslype, C.; et al. Cetuximab Monotherapy and Cetuximab plus Irinotecan in Irinotecan-Refractory Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cutsem, E.; Köhne, C.H.; Hitre, E.; Zaluski, J.; Chang Chien, C.R.; Makhson, A.; D’Haens, G.; Pintér, T.; Lim, R.; Bodoky, G.; et al. Cetuximab and Chemotherapy as Initial Treatment for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 1408–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokemeyer, C.; Bondarenko, I.; Makhson, A.; Hartmann, J.T.; Aparicio, J.; De Braud, F.; Donea, S.; Ludwig, H.; Schuch, G.; Stroh, C.; et al. Fluorouracil, Leucovorin, and Oxaliplatin With and Without Cetuximab in the First-Line Treatment of Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, J.; Muro, K.; Shitara, K.; Yamazaki, K.; Shiozawa, M.; Ohori, H.; Takashima, A.; Yokota, M.; Makiyama, A.; Akazawa, N.; et al. Panitumumab vs Bevacizumab Added to Standard First-line Chemotherapy and Overall Survival Among Patients with RAS Wild-type, Left-Sided Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2023, 329, 1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brudvik, K.W.; Jones, R.P.; Giuliante, F.; Shindoh, J.; Passot, G.; Chung, M.H.; Song, J.; Li, L.; Dagenborg, V.J.; Fretland, Å.A.; et al. RAS Mutation Clinical Risk Score to Predict Survival After Resection of Colorectal Liver Metastases. Ann. Surg. 2019, 269, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Heo, J.S.; Lee, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Lee, M.Y.; Lim, S.H.; Lee, W.H.; Kim, S.H.; Park, Y.A.; Cho, B.Y.; et al. The impact of KRAS mutations on prognosis in surgically resected colorectal cancer patients with liver and lung metastases: A retrospective analysis. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.P.; Jackson, R.; Dunne, D.F.J.; Malik, H.Z.; Fenwick, S.W.; Poston, G.J.; Ghaneh, P. Systematic review and meta-analysis of follow-up after hepatectomy for colorectal liver metastases2. Br. J. Surg. 2012, 99, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okkabaz, N.; Haksal, M.C.; Öncel, M. Laparoscopic Resection of Primary Tumor with Synchronous Conventional Resection of Liver Metastases in Patients with Stage 4 Colorectal Cancer: A Retrospective Analysis. Turk. J. Color. Dis. 2019, 29, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsek, M.; Besiroglu, M.; Akcakaya, A.; Topcu, A.; Yasin, A.I.; Isleyen, Z.S.; Seker, M.; Turk, H.M. Local interventions for colorectal cancer metastases to liver and lung. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2023, 192, 2635–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawlik, T.M.; Scoggins, C.R.; Zorzi, D.; Abdalla, E.K.; Andres, A.; Eng, C.; Curley, S.A.; Loyer, E.M.; Muratore, A.; Mentha, G.; et al. Effect of Surgical Margin Status on Survival and Site of Recurrence After Hepatic Resection for Colorectal Metastases. Ann. Surg. 2005, 241, 715–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, J.S.; Jarnagin, W.R.; DeMatteo, R.P.; Fong, Y.; Kornprat, P.; Gonen, M.; Kemeny, N.; Brennan, M.F.; Blumgart, L.H.; D’Angelica, M. Actual 10-Year Survival After Resection of Colorectal Liver Metastases Defines Cure. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 4575–4580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, M.; Tekkis, P.P.; Welsh, F.K.S.; O’Rourke, T.; John, T.G. Evaluation of Long-term Survival After Hepatic Resection for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Multifactorial Model of 929 Patients. Ann. Surg. 2008, 247, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charnsangavej, C.; Clary, B.; Fong, Y.; Grothey, A.; Pawlik, T.M.; Choti, M.A. Selection of Patients for Resection of Hepatic Colorectal Metastases: Expert Consensus Statement. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2006, 13, 1261–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buisman, F.E.; Giardiello, D.; Kemeny, N.E.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Höppener, D.J.; Galjart, B.; Nierop, P.M.; Balachandran, V.P.; Cercek, A.; Drebin, J.A.; et al. Predicting 10-year survival after resection of colorectal liver metastases; an international study including biomarkers and perioperative treatment. Eur. J. Cancer 2022, 168, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakemeyer, L.; Sander, S.; Wittau, M.; Henne-Bruns, D.; Kornmann, M.; Lemke, J. Diagnostic and Prognostic Value of CEA and CA19-9 in Colorectal Cancer. Diseases 2021, 9, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gramkow, M.H.; Mosgaard, C.S.; Schou, J.V.; Nordvig, E.H.; Dolin, T.G.; Lykke, J.; Nielsen, D.L.; Pfeiffer, P.; Qvortrup, C.; Yilmaz, M.K.; et al. The prognostic role of circulating CA19–9 and CEA in patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer Treat. Res. Commun. 2025, 43, 100907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fong, Y.; Fortner, J.; Sun, R.L.; Brennan, M.F.; Blumgart, L.H. Clinical Score for Predicting Recurrence After Hepatic Resection for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: Analysis of 1001 Consecutive Cases. Ann. Surg. 1999, 230, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denbo, J.W.; Yamashita, S.; Passot, G.; Egger, M.; Chun, Y.S.; Kopetz, S.E.; Maru, D.; Brudvik, K.W.; Wei, S.H.; Conrad, C.; et al. RAS Mutation Is Associated with Decreased Survival in Patients Undergoing Repeat Hepatectomy for Colorectal Liver Metastases. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2017, 21, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vauthey, J.N.; Zimmitti, G.; Kopetz, S.E.; Shindoh, J.; Chen, S.S.; Andreou, A.; Curley, S.A.; Aloia, T.A.; Maru, D.M. RAS Mutation Status Predicts Survival and Patterns of Recurrence in Patients Undergoing Hepatectomy for Colorectal Liver Metastases. Ann. Surg. 2013, 258, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Metastasectomy (n = 185) | No Metastasectomy (n = 894) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (median [IQR]) | 62.0 (IQR 11) | 60.5 (IQR 15) | 0.084 |

| BMI, kg/m2 (median [IQR]) | 26.35 (IQR 6.27) | 25.48 (IQR 7.13) | 0.689 |

| Sex | 0.799 | ||

| Female | 62 (33.5%) | 308 (34.5%) | |

| Male | 123 (66.5%) | 585 (65.5%) | |

| Missing | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.1%) | |

| ECOG performance status | 0.103 | ||

| ECOG 0–1 | 111 (60.0%) | 473 (52.9%) | |

| ECOG 2–4 | 5 (2.7%) | 46 (5.1%) | |

| Missing | 69 (37.3%) | 375 (41.9%) | |

| Smoking status | 0.206 | ||

| Current smoker | 27 (14.6%) | 159 (17.8%) | |

| Former smoker | 27 (14.6%) | 102 (11.4%) | |

| Never smoker | 45 (24.3%) | 265 (29.6%) | |

| Missing | 86 (46.5%) | 368 (41.2%) | |

| Primary tumor location | 0.153 | ||

| Rectum | 62 (33.5%) | 326 (36.5%) | |

| Left colon | 91 (49.2%) | 373 (41.7%) | |

| Right colon | 30 (16.2%) | 183 (20.5%) | |

| Missing | 2 (1.1%) | 12 (1.3%) | |

| Histological grade | <0.001 | ||

| Grade 1 | 18 (9.7%) | 65 (7.3%) | |

| Grade 2 | 84 (45.4%) | 249 (27.9%) | |

| Grade 3 | 17 (9.2%) | 77 (8.6%) | |

| Missing | 66 (35.7%) | 503 (56.3%) | |

| Mucinous component | <0.001 | ||

| Non-mucinous | 74 (40.0%) | 264 (29.5%) | |

| Mucinous | 23 (12.4%) | 48 (5.4%) | |

| Missing | 88 (47.6%) | 582 (65.1%) | |

| MSI status | <0.001 | ||

| MSI-H | 16 (8.6%) | 45 (5.0%) | |

| MSS | 66 (35.7%) | 213 (23.8%) | |

| Missing | 103 (55.7%) | 636 (71.1%) | |

| BRAF mutation status | 0.570 | ||

| Mutant | 2 (1.1%) | 18 (2.0%) | |

| Wild type | 114 (61.6%) | 524 (58.6%) | |

| Not tested | 69 (37.3%) | 352 (39.4%) | |

| Site of metastasis | 0.001 | ||

| Liver | 157 (84.9%) | 603 (67.4%) | |

| Lung | 6 (3.2%) | 74 (8.3%) | |

| Lymph node | 6 (3.2%) | 80 (8.9%) | |

| Peritoneal | 10 (5.4%) | 78 (8.7%) | |

| Other | 6 (3.2%) | 57 (6.4%) | |

| Number of metastatic organs | 0.164 | ||

| 1 | 124 (67.0%) | 530 (59.3%) | |

| 2 | 50 (27.0%) | 272 (30.4%) | |

| 3 | 10 (5.4%) | 79 (8.8%) | |

| 4 | 1 (0.5%) | 12 (1.3%) | |

| Missing | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.1%) | |

| Liver-only metastasis | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 102 (55.1%) | 321 (35.9%) | |

| No | 83 (44.9%) | 573 (64.1%) | |

| Number of systemic therapy lines received | 0.084 | ||

| 0 | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (0.2%) | |

| 1 | 5 (2.7%) | 12 (1.3%) | |

| 2 | 64 (34.6%) | 343 (38.4%) | |

| 3 | 53 (28.6%) | 309 (34.6%) | |

| 4 | 44 (23.8%) | 144 (16.1%) | |

| 5 | 19 (10.3%) | 84 (9.4%) | |

| Baseline CEA, ng/mL (median [IQR]) | 32.0 (IQR 107) | 77.0 (IQR 261) | <0.001 |

| Baseline CA19-9, U/mL (median [IQR]) | 25.0 (IQR 73) | 38.5 (IQR 202) | 0.047 |

| Section | Characteristic | Category | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 185 | |||

| Metastatic disease | Type of metastatic presentation | Synchronous metastatic disease | 136 | 73.5 |

| Metachronous metastatic disease | 49 | 26.5 | ||

| Main metastatic site at diagnosis | Liver | 157 | 84.9 | |

| Peritoneum | 10 | 5.4 | ||

| Lung | 6 | 3.2 | ||

| Lymph node | 6 | 3.2 | ||

| Adrenal | 1 | 0.5 | ||

| Brain | 2 | 1.1 | ||

| Other | 3 | 1.6 | ||

| Metastasectomy details | Timing of metastasectomy | Synchronous/upfront (de novo or synchronous resection) | 128 | 69.2 |

| Metachronous (after primary tumor surgery) | 49 | 26.5 | ||

| After systemic therapy | 8 | 4.3 | ||

| Site of metastasectomy | Liver | 145 | 78.4 | |

| Missing | 20 | 10.8 | ||

| Lung | 12 | 6.5 | ||

| Lymph node | 4 | 2.2 | ||

| Brain | 2 | 1.1 | ||

| Bone | 1 | 0.5 | ||

| Adrenal | 1 | 0.5 | ||

| Number of metastatic organs at metastasectomy | 1 | 124 | 67.0 | |

| 2 | 50 | 27.0 | ||

| 3 | 10 | 5.4 | ||

| 4 | 1 | 0.5 |

| Variable | Comparison/Unit | HR | 95% CI | p-Value | N Used | Events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female vs. Male | 0.571 | 0.320–1.021 | 0.059 | 180 | 58 |

| Age | Per 1 year | 1.006 | 0.981–1.032 | 0.638 | 179 | 58 |

| Smoking status | Per 1 category increase | 1.112 | 0.714–1.731 | 0.638 | 96 | 32 |

| ECOG category | ECOG 0–1 vs. ECOG 2–4 | 1.397 | 0.191–10.243 | 0.742 | 113 | 34 |

| Number of metastatic organs | Per 1 organ | 0.937 | 0.620–1.415 | 0.756 | 180 | 58 |

| Liver-only metastasis | Yes vs. No | 1.027 | 0.613–1.723 | 0.919 | 180 | 58 |

| Primary sidedness | Right vs. Left | 1.547 | 0.791–3.026 | 0.202 | 178 | 56 |

| Mucinous histology | Mucinous vs. Non-mucinous | 1.098 | 0.454–2.654 | 0.835 | 96 | 25 |

| MSI status | MSI-H vs. MSS | 0.686 | 0.157–2.999 | 0.616 | 81 | 21 |

| log10 CA19-9 | Per 1 log10 unit | 1.814 | 1.198–2.748 | 0.005 | 88 | 24 |

| log10 CEA | Per 1 log10 unit | 0.800 | 0.515–1.244 | 0.322 | 99 | 26 |

| CEA baseline | Below vs. Above threshold | 0.576 | 0.172–1.931 | 0.371 | 99 | 26 |

| CA19-9 baseline | Below vs. Above threshold | 0.370 | 0.158–0.862 | 0.021 | 88 | 24 |

| Grade | Grade 1–2 vs. 3 | 3.160 | 0.747–13.366 | 0.118 | 118 | 34 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ökten, İ.N.; Baydaş, T.; Yıldırım, M.E.; Bilir, C.; Yalçın, Ş.; Çubukçu, E.; Tanrıkulu Şimşek, E.; Aslan, Ç.; Dane, F.; Çelik, S.; et al. Real-World Survival Outcomes Following Metastasectomy in RAS Wild-Type mCRC: Insights from a Multicentre National Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 467. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020467

Ökten İN, Baydaş T, Yıldırım ME, Bilir C, Yalçın Ş, Çubukçu E, Tanrıkulu Şimşek E, Aslan Ç, Dane F, Çelik S, et al. Real-World Survival Outcomes Following Metastasectomy in RAS Wild-Type mCRC: Insights from a Multicentre National Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(2):467. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020467

Chicago/Turabian StyleÖkten, İlker Nihat, Tuba Baydaş, Mahmut Emre Yıldırım, Cemil Bilir, Şuayib Yalçın, Erdem Çubukçu, Eda Tanrıkulu Şimşek, Çağatay Aslan, Faysal Dane, Sinemis Çelik, and et al. 2026. "Real-World Survival Outcomes Following Metastasectomy in RAS Wild-Type mCRC: Insights from a Multicentre National Cohort Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 2: 467. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020467

APA StyleÖkten, İ. N., Baydaş, T., Yıldırım, M. E., Bilir, C., Yalçın, Ş., Çubukçu, E., Tanrıkulu Şimşek, E., Aslan, Ç., Dane, F., Çelik, S., Bilici, A., Şendur, M. A. N., Öven, B. B., Işıkdoğan, A., Türk, H. M., Karaca, M., Karabulut, B., Özçelik, M., Gümüş, M., ... Karadurmuş, N. (2026). Real-World Survival Outcomes Following Metastasectomy in RAS Wild-Type mCRC: Insights from a Multicentre National Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(2), 467. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020467