Association Between Septal Implantation Level and Pacing Threshold Stability in Leadless Pacemaker Implantation

Abstract

1. Introduction

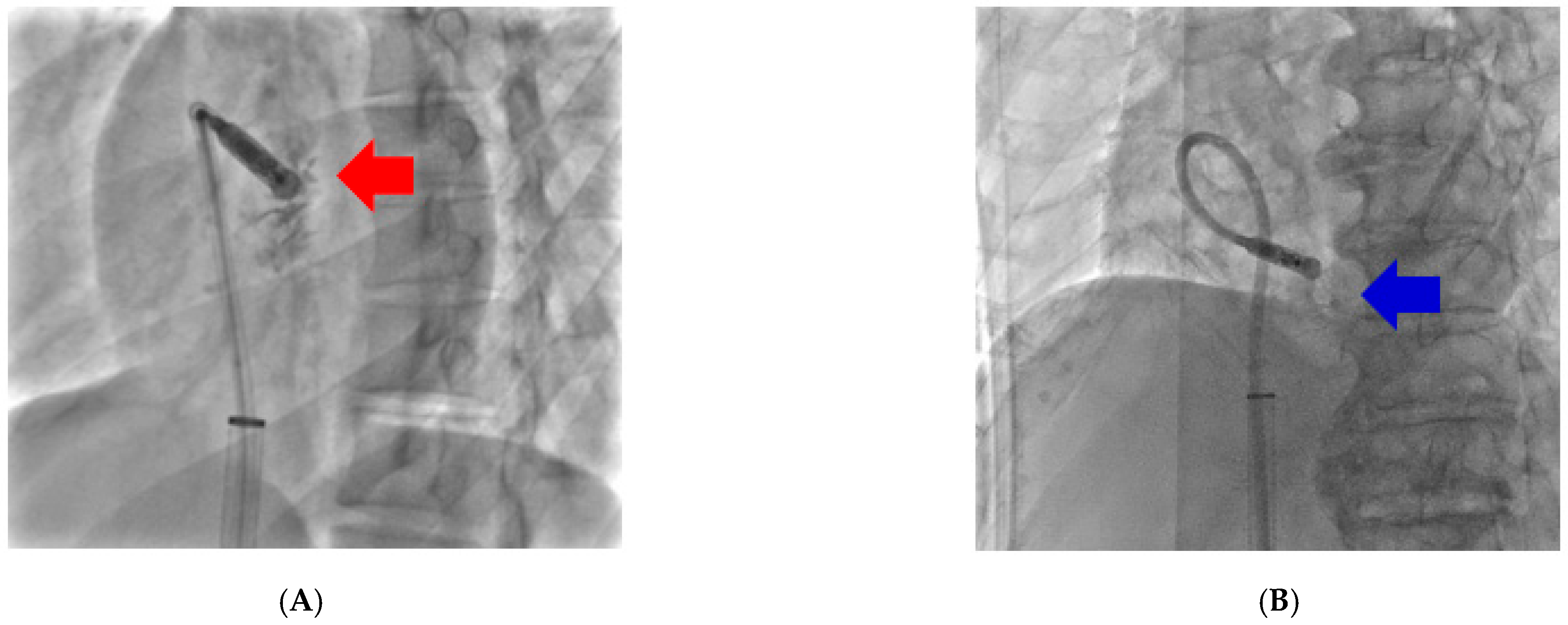

2. Methods

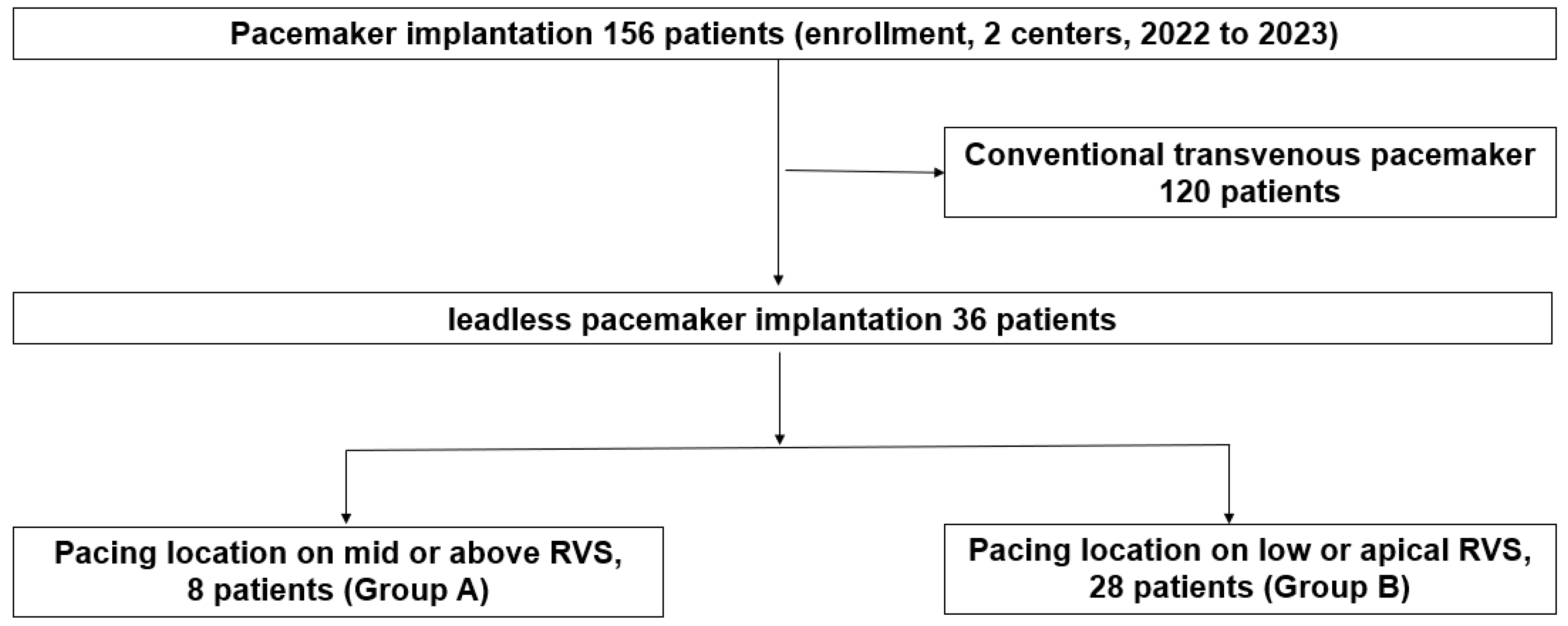

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Procedure for Implantation of AF Ablation

2.3. Postprocedural Follow-Up

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. IRB and Ethical Approval

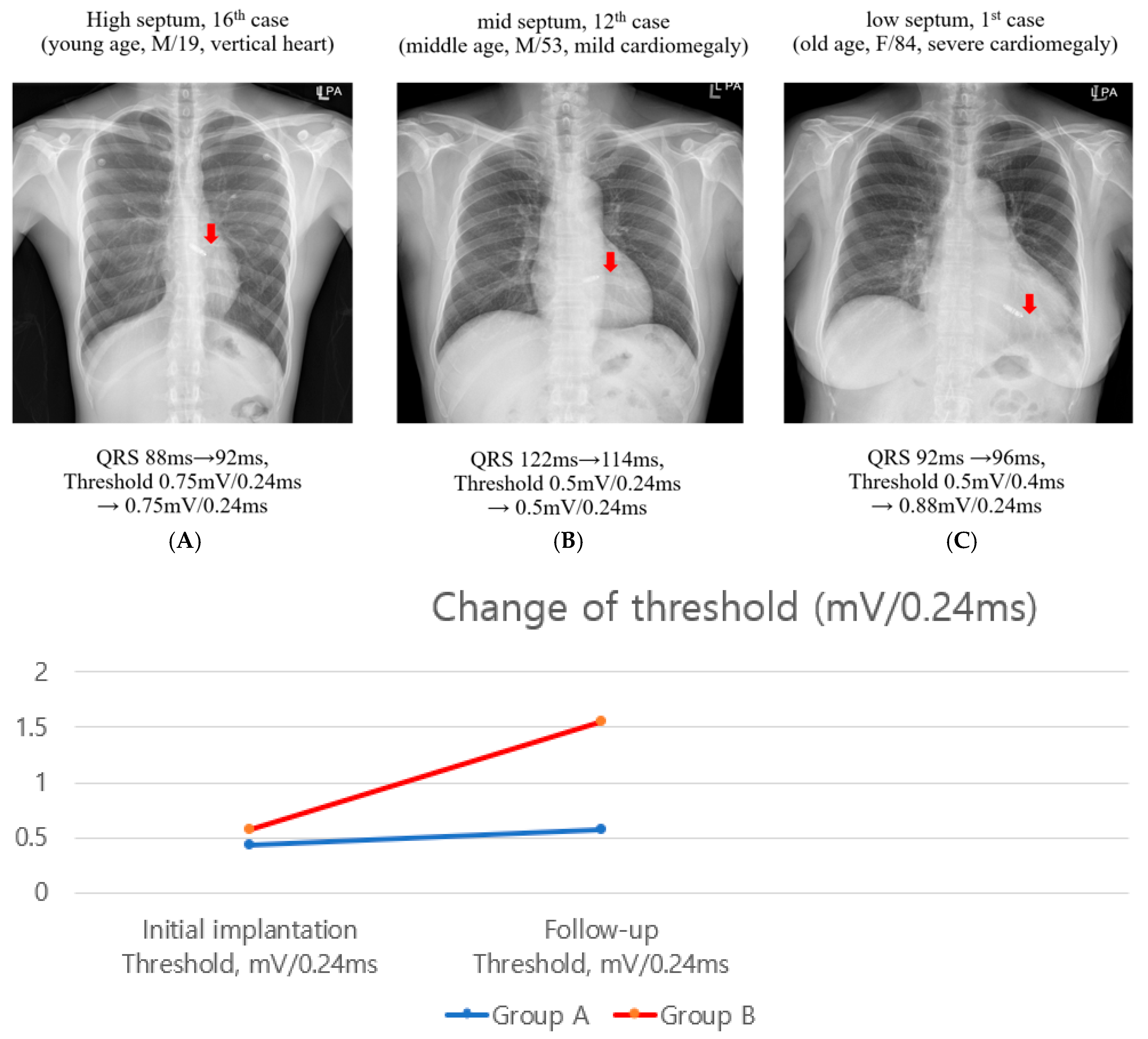

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Follow-Up Pacing Thresholds

3.3. Changes in Echocardiographic and Electrical Parameters

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Comparison of Recent Guidelines

4.3. Pacing Threshold Change of Mid-Term Follow-Up

4.4. Clinical Studies and What’s New Findings on This Study

4.5. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- El-Chami, M.F.; Garweg, C.; Clementy, N.; Al-Samadi, F.; Iacopino, S.; Martinez-Sande, J.L.; Roberts, P.R.; Tondo, C.; Johansen, J.B.; Vinolas-Prat, X.; et al. Leadless pacemakers at 5-year follow-up: The Micra transcatheter pacing system post-approval registry. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 1241–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Palmisano, P.; Facchin, D.; Ziacchi, M.; Nigro, G.; Nicosia, A.; Bongiorni, M.G.; Tomasi, L.; Rossi, A.; De Filippo, P.; Sgarito, G.; et al. Rate and nature of complications with leadless transcatheter pacemakers compared with transvenous pacemakers: Results from an Italian multicentre large population analysis. Europace 2023, 25, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Middour, T.G.; Chen, J.H.; El-Chami, M.F. Leadless pacemakers: A review of current data and future directions. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2021, 66, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garweg, C.; Vandenberk, B.; Foulon, S.; Haemers, P.; Ector, J.; Willems, R. Leadless pacing with Micra TPS: A comparison between right ventricular outflow tract, mid-septal, and apical implant sites. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2019, 30, 2002–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hai, J.J.; Fang, J.; Tam, C.C.; Wong, C.K.; Un, K.C.; Siu, C.W.; Lau, C.P.; Tse, H.F. Safety and feasibility of a midseptal implantation technique of a leadless pacemaker. Heart Rhythm. 2019, 16, 896–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Zhou, X.; Lu, Y.; Li, Y.; Xing, Q.; Tuerhong, Z.; Yang, X.; Xiaokereti, J.; Guo, Y.; Zhou, X.; et al. Computed Tomography-Verified Pacing Location of Micra Leadless Pacemakers and Characteristics of Paced Electrocardiograms in Bradycardia Patients. Clin. Cardiol. 2025, 48, e70209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sharma, P.; Singh Guleria, V.; Bharadwaj, P.; Datta, R. Assessing safety of leadless pacemaker (MICRA) at various implantation sites and its impact on paced QRS in Indian population. Indian Heart J. 2020, 72, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, Y.; Xing, Q.; Xiaokereti, J.; Chen, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, X.; Lu, Y.; Tuerhong, Z.; Tang, B. Right ventriculography improves the accuracy of leadless pacemaker implantation in right ventricular mid-septum. J. Interv. Card. Electrophysiol. 2023, 66, 941–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Crucean, A.; Spicer, D.E.; Tretter, J.T.; Mohun, T.J.; Anderson, R.H. Revisiting the anatomy of the right ventricle in the light of knowledge of its development. J. Anat. 2024, 244, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chung, M.K.; Patton, K.K.; Lau, C.P.; Dal Forno, A.R.J.; Al-Khatib, S.M.; Arora, V.; Birgersdotter-Green, U.M.; Cha, Y.M.; Chung, E.H.; Cronin, E.M.; et al. 2023 HRS/APHRS/LAHRS guideline on cardiac physiologic pacing for the avoidance and mitigation of heart failure. Heart Rhythm. 2023, 20, e17–e91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Burri, H.; Jastrzebski, M.; Cano, Ó.; Čurila, K.; de Pooter, J.; Huang, W.; Israel, C.; Joza, J.; Romero, J.; Vernooy, K.; et al. EHRA clinical consensus statement on conduction system pacing implantation: Endorsed by the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), Canadian Heart Rhythm Society (CHRS), and Latin American Heart Rhythm Society (LAHRS). Europace 2023, 25, 1208–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Blank, E.A.; El-Chami, M.F.; Wenger, N.K. Leadless Pacemakers: State of the Art and Selection of the Ideal Candidate. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2023, 19, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Reddy, V.Y.; Miller, M.A.; Knops, R.E.; Neuzil, P.; Defaye, P.; Jung, W.; Doshi, R.; Castellani, M.; Strickberger, A.; Mead, R.H.; et al. Retrieval of the Leadless Cardiac Pacemaker: A Multicenter Experience. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2016, 9, e004626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salaun, E.; Tovmassian, L.; Simonnet, B.; Giorgi, R.; Franceschi, F.; Koutbi-Franceschi, L.; Hourdain, J.; Habib, G.; Deharo, J.C. Right ventricular and tricuspid valve function in patients chronically implanted with leadless pacemakers. Europace 2018, 20, 823–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triposkiadis, F.; Xanthopoulos, A.; Boudoulas, K.D.; Giamouzis, G.; Boudoulas, H.; Skoularigis, J. The Interventricular Septum: Structure, Function, Dysfunction, and Diseases. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jongbloed, M.R.; Wijffels, M.C.; Schalij, M.J.; Blom, N.A.; Poelmann, R.E.; van der Laarse, A.; Mentink, M.M.; Wang, Z.; Fishman, G.I.; Gittenberger-de Groot, A.C. Development of the right ventricular inflow tract and moderator band: A possible morphological and functional explanation for Mahaim tachycardia. Circ. Res. 2005, 96, 776–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusu, S.; Mera, H.; Hoshida, K.; Miyakoshi, M.; Miwa, Y.; Tsukada, T.; Yoshino, H.; Ikeda, T. Selective site pacing from the right ventricular mid-septum. Follow-up of lead performance and procedure technique. Int. Heart J. 2012, 53, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.H.; Chen, C.; Xing, Q.; Zhou, X.H.; Li, Y.D.; Zhang, L.; Lu, Y.M.; Tu-Erhong, Z.K.; Yang, X.; Liu, X.B.; et al. Study of the optimum fluoroscopic angle for the implant fixation test of a leadless cardiac pacemaker. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2022, 38, 2801–2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Reynolds, D.; Duray, G.Z.; Omar, R.; Soejima, K.; Neuzil, P.; Zhang, S.; Narasimhan, C.; Steinwender, C.; Brugada, J.; Lloyd, M.; et al. A Leadless Intracardiac Transcatheter Pacing System. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, P.R.; Clementy, N.; Al Samadi, F.; Garweg, C.; Martinez-Sande, J.L.; Iacopino, S.; Johansen, J.B.; Vinolas Prat, X.; Kowal, R.C.; Klug, D.; et al. A leadless pacemaker in the real-world setting: The Micra Transcatheter Pacing System Post-Approval Registry. Heart Rhythm. 2017, 14, 1375–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd, M.S.; El-Chami, M.F.; Nilsson, K.R., Jr.; Cantillon, D.J. Transcatheter/leadless pacing. Heart Rhythm. 2018, 15, 624–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, P.R.; ElRefai, M.; Foley, P.; Rao, A.; Sharman, D.; Somani, R.; Sporton, S.; Wright, G.; Zaidi, A.; Pepper, C. UK Expert Consensus Statement for the Optimal Use and Clinical Utility of Leadless Pacing Systems on Behalf of the British Heart Rhythm Society. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. Rev. 2022, 11, e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gao, X.F.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, J.S.; Ning-Zhang Pan, X.H.; Xu, Y.Z. Impact of leadless pacemaker implantation site on cardiac synchronization and tricuspid regurgitation. Egypt. Heart J. 2025, 77, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Katritsis, D.G.; Calkins, H. Septal and Conduction System Pacing. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. Rev. 2023, 12, e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yu, Y.; Yang, X.; Lian, X.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, B.; Feng, X.; Wang, Q.; Li, Y. Micra Leadless and Transvenous Pacemaker: A Single-Center Comparative Study of QRS Wave Duration Resulting From Different Pacing Sites. Ann. Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2025, 30, e70050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, Q.Y.; Dong, J.Z.; Guo, C.J.; Fang, D.P.; Liu, X.; Dai, W.L. Initial studies on the implanting sites of high and low ventricular septa using leadless cardiac pacemakers. Ann. Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2023, 28, e13068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Saleem-Talib, S.; Hoevenaars, C.P.R.; Molitor, N.; van Driel, V.J.; van der Heijden, J.; Breitenstein, A.; van Wessel, H.; van Schie, M.S.; de Groot, N.M.S.; Ramanna, H. Leadless pacing: A comprehensive review. Eur. Heart J. 2025, 46, 1979–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yarmohammadi, H.; Batra, J.; Hennessey, J.A.; Kochav, S.; Saluja, D.; Liu, Q. Novel use of 3-dimensional transthoracic echocardiography to guide implantation of a leadless pacemaker system. HeartRhythm Case Rep. 2022, 8, 366–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Arai, H.; Mizukami, A.; Hanyu, Y.; Kawakami, T.; Shimizu, Y.; Hiroki, J.; Yoshioka, K.; Ohtani, H.; Ono, M.; Yamashita, S.; et al. Leadless pacemaker implantation sites confirmed by computed tomography and their parameters and complication rates. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 2022, 45, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, R.M.; Badano, L.P.; Mor-Avi, V.; Afilalo, J.; Armstrong, A.; Ernande, L.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Foster, E.; Goldstein, S.A.; Kuznetsova, T.; et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: An update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2015, 16, 233–270, Erratum in Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2016, 17, 412. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjci/jew041. Erratum in Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2016, 17, 969. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjci/jew124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badano, L.P.; Kolias, T.J.; Muraru, D.; Abraham, T.P.; Aurigemma, G.; Edvardsen, T.; D’Hooge, J.; Donal, E.; Fraser, A.G.; Marwick, T.; et al. Standardization of left atrial, right ventricular, and right atrial deformation imaging using two-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography: A consensus document of the EACVI/ASE/Industry Task Force to standardize deformation imaging. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2018, 19, 591–600, Erratum in Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2018, 19, 830–833. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjci/jey071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hai, J.J.; Mao, Y.; Zhen, Z.; Fang, J.; Wong, C.K.; Siu, C.W.; Yiu, K.H.; Lau, C.P.; Tse, H.F. Close Proximity of Leadless Pacemaker to Tricuspid Annulus Predicts Worse Tricuspid Regurgitation Following Septal Implantation. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2021, 14, e009530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garweg, C.; Duchenne, J.; Vandenberk, B.; Mao, Y.; Ector, J.; Haemers, P.; Poels, P.; Voigt, J.U.; Willems, R. Evolution of ventricular and valve function in patients with right ventricular pacing—A randomized controlled trial comparing leadless and conventional pacing. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 2023, 46, 1455–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breeman, K.T.N.; du Long, R.; Beurskens, N.E.G.; van der Wal, A.C.; Wilde, A.A.M.; Tjong, F.V.Y.; Knops, R.E. Tissues attached to retrieved leadless pacemakers: Histopathological evaluation of tissue composition in relation to implantation time and complications. Heart Rhythm. 2021, 18, 2101–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beurskens, N.E.G.; Tjong, F.V.Y.; de Bruin-Bon, R.H.A.; Dasselaar, K.J.; Kuijt, W.J.; Wilde, A.A.M.; Knops, R.E. Impact of Leadless Pacemaker Therapy on Cardiac and Atrioventricular Valve Function Through 12 Months of Follow-Up. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2019, 12, e007124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Fazia, V.M.; Lepone, A.; Pierucci, N.; Gianni, C.; Barletta, V.; Mohanty, S.; Della Rocca, D.G.; La Valle, C.; Torlapati, P.G.; Al-Ahmad, M.; et al. Low prevalence of new-onset severe tricuspid regurgitation following leadless pacemaker implantation in a large series of consecutive patients. Heart Rhythm. 2024, 21, 2603–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Group A, n = 8 (Mid or Above RVS) | Group B, n = 28 (Lower RVS) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 58.8 ± 17.3 | 70.9 ± 13.4 | 0.100 |

| Sex, male, n (%) | 5 (62.5%) | 14 (50.0%) | 0.695 |

| Pacemaker indication AV block, n (%) | 4 (30.7%) | 5 (19.2%) | 0.414 |

| Initial QRS duration, ms | 118.2 ± 35.1 | 119.9 ± 37.7 | 0.909 |

| Initial implantation Threshold, mV/0.24 ms | 0.43 ± 0.20 | 0.58 ± 0.51 | 0.238 |

| Follow-up Threshold, mV/0.24 ms | 0.57 ± 0.09 | 1.55 ± 0.97 | <0.001 |

| Group A (Mid or Above RVS) | Group B (Lower RVS) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LVFE (%) | |||

| Pre-implantation | 61.05 ± 8.393 | 64.42 ± 6.32 | 0.584 |

| Post-implantation | 63.68 ± 8.68 | 64.08 ± 5.50 | 0.600 |

| Change of LVEF | 2.33 ± 2.34 | −0.32 ± 1.22 | 0.129 |

| QRS duration (ms) | |||

| Pre-implantation | 118.2 ± 35.1 | 119.9 ± 37.7 | 0.909 |

| Post-implantation | 111.6 ± 22.4 | 123.5 ± 41.8 | 0.279 |

| Change of QRS duration | 6.0 ± 12.7 | 13.5 ± 42.8 | 0.791 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kim, D.-H.; Kim, Y.; Lee, S.W.; Kang, J.; Park, J. Association Between Septal Implantation Level and Pacing Threshold Stability in Leadless Pacemaker Implantation. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 468. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020468

Kim D-H, Kim Y, Lee SW, Kang J, Park J. Association Between Septal Implantation Level and Pacing Threshold Stability in Leadless Pacemaker Implantation. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(2):468. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020468

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Dong-Hyeok, Yeji Kim, Seung Woo Lee, Jeongmin Kang, and Junbeom Park. 2026. "Association Between Septal Implantation Level and Pacing Threshold Stability in Leadless Pacemaker Implantation" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 2: 468. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020468

APA StyleKim, D.-H., Kim, Y., Lee, S. W., Kang, J., & Park, J. (2026). Association Between Septal Implantation Level and Pacing Threshold Stability in Leadless Pacemaker Implantation. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(2), 468. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020468