Diagnostic Performance of a DOAC Urine Dipstick in Obese Outpatients with Atrial Fibrillation: Comparison with Plasma Concentrations

Abstract

1. Introduction

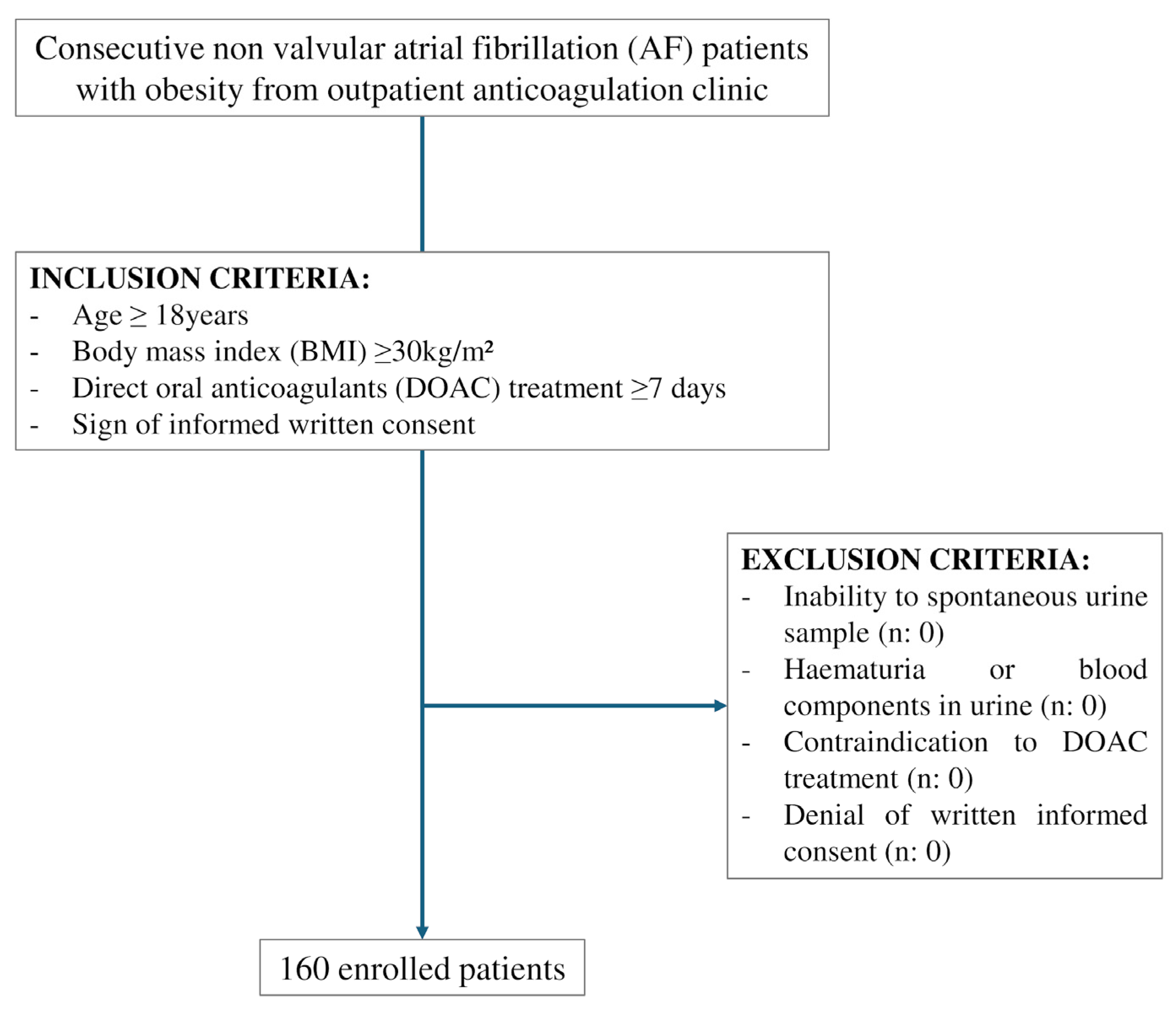

2. Methods

2.1. Calculation of Sample Size

2.2. Definition of Obesity

2.3. Blood Sampling of DOAC and Plasma Concentrations Assessment

2.4. DOAC Dipstick

2.5. Study Endpoints

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

3.2. Primary Outcome

3.2.1. Point-of-Care Sensitivity, Specificity, Accuracy Compared to Trough Plasma Concentrations

3.2.2. Point-of-Care Sensitivity, Specificity, Accuracy Compared to Trough Plasma Concentrations According to Anti-Xa Inhibitors and Anti-IIa Inhibitors

3.3. Secondary Outcome

3.3.1. Point-of-Care Sensitivity, Specificity, Accuracy Compared to Peak Plasma Concentration

3.3.2. Point-of-Care Sensitivity, Specificity, Accuracy Compared to Plasma Concentration Threshold > 30 ng/mL

3.4. Subgroup Analyses

3.4.1. Subgroup Analysis According to Type of DOAC

3.4.2. Subgroup Analysis According to Obesity Class and Body Weight

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical Implications

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

4.3. Future Prospectives

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Middlekauff, H.R.; Stevenson, W.G.; Stevenson, L.W. Prognostic significance of atrial fibrillation in advanced heart failure. A study of 390 patients. Circulation 1991, 84, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: A pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128.9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet 2017, 390, 2627–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bluher, M. Obesity: Global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.J.; Chen, Y.H.; Lin, F.Y.; Hsieh, L.Y.; Wang, S.H.; Lin, C.Y.; Wang, Y.C.; Ku, H.H.; Chen, J.W.; Chen, Y.L. Pravastatin induces thrombomodulin expression in TNFalpha-treated human aortic endothelial cells by inhibiting Rac1 and Cdc42 translocation and activity. J. Cell. Biochem. 2007, 101, 642–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, A.; Peralta, M.; Naia, A.; Loureiro, N.; de Matos, M.G. Prevalence of adult overweight and obesity in 20 European countries, 2014. Eur. J. Public Health 2018, 28, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piche, M.E.; Tchernof, A.; Despres, J.P. Obesity Phenotypes, Diabetes, and Cardiovascular Diseases. Circ. Res. 2020, 126, 1477–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivimaki, M.; Strandberg, T.; Pentti, J.; Nyberg, S.T.; Frank, P.; Jokela, M.; Ervasti, J.; Suominen, S.B.; Vahtera, J.; Sipila, P.N.; et al. Body-mass index and risk of obesity-related complex multimorbidity: An observational multicohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022, 10, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregson, J.; Kaptoge, S.; Bolton, T.; Pennells, L.; Willeit, P.; Burgess, S.; Bell, S.; Sweeting, M.; Rimm, E.B.; Kabrhel, C.; et al. Cardiovascular Risk Factors Associated with Venous Thromboembolism. JAMA Cardiol. 2019, 4, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Bruzelius, M.; Xiong, Y.; Hakansson, N.; Akesson, A.; Larsson, S.C. Overall and abdominal obesity in relation to venous thromboembolism. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2021, 19, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, R.; Baines, O.; Hayes, A.; Tompkins, K.; Kalla, M.; Holmes, A.P.; O’Shea, C.; Pavlovic, D. Impact of Obesity on Atrial Fibrillation Pathogenesis and Treatment Options. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e032277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindricks, G.; Potpara, T.; Dagres, N.; Arbelo, E.; Bax, J.J.; Blomstrom-Lundqvist, C.; Boriani, G.; Castella, M.; Dan, G.A.; Dilaveris, P.E.; et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 373–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruff, C.T.; Giugliano, R.P.; Braunwald, E.; Morrow, D.A.; Murphy, S.A.; Kuder, J.F.; Deenadayalu, N.; Jarolim, P.; Betcher, J.; Shi, M.; et al. Association between edoxaban dose, concentration, anti-Factor Xa activity, and outcomes: An analysis of data from the randomised, double-blind ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 trial. Lancet 2015, 385, 2288–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reilly, P.A.; Lehr, T.; Haertter, S.; Connolly, S.J.; Yusuf, S.; Eikelboom, J.W.; Ezekowitz, M.D.; Nehmiz, G.; Wang, S.; Wallentin, L.; et al. The effect of dabigatran plasma concentrations and patient characteristics on the frequency of ischemic stroke and major bleeding in atrial fibrillation patients: The RE-LY Trial (Randomized Evaluation of Long-Term Anticoagulation Therapy). J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 63, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunois, C. Laboratory Monitoring of Direct Oral Anticoagulants (DOACs). Biomedicines 2021, 9, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripodi, A. The laboratory and the direct oral anticoagulants. Blood 2013, 121, 4032–4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowther, M.; Cuker, A. How can we reverse bleeding in patients on direct oral anticoagulants? Kardiol. Pol. 2019, 77, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douxfils, J.; Adcock, D.M.; Bates, S.M.; Favaloro, E.J.; Gouin-Thibault, I.; Guillermo, C.; Kawai, Y.; Lindhoff-Last, E.; Kitchen, S.; Gosselin, R.C. 2021 Update of the International Council for Standardization in Haematology Recommendations for Laboratory Measurement of Direct Oral Anticoagulants. Thromb. Haemost. 2021, 121, 1008–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffel, J.; Collins, R.; Antz, M.; Cornu, P.; Desteghe, L.; Haeusler, K.G.; Oldgren, J.; Reinecke, H.; Roldan-Schilling, V.; Rowell, N.; et al. 2021 European Heart Rhythm Association Practical Guide on the Use of Non-Vitamin K Antagonist Oral Anticoagulants in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. Europace 2021, 23, 1612–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harenberg, J.; Gosselin, R.C.; Cuker, A.; Becattini, C.; Pabinger, I.; Poli, S.; Weitz, J.; Ageno, W.; Bauersachs, R.; Celap, I.; et al. Algorithm for Rapid Exclusion of Clinically Relevant Plasma Levels of Direct Oral Anticoagulants in Patients Using the DOAC Dipstick: An Expert Consensus Paper. Thromb. Haemost. 2024, 124, 770–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harenberg, J.; Du, S.; Wehling, M.; Zolfaghari, S.; Weiss, C.; Kramer, R.; Walenga, J. Measurement of dabigatran, rivaroxaban and apixaban in samples of plasma, serum and urine, under real life conditions. An international study. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2016, 54, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menichelli, D.; Pannunzio, A.; Baldacci, E.; Cammisotto, V.; Castellani, V.; Mormile, R.; Palumbo, I.M.; Chistolini, A.; Violi, F.; Harenberg, J.; et al. Plasma Concentrations of Direct Oral Anticoagulants in Patients with Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation and Different Degrees of Obesity. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2025, 64, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gosselin, R.C.; Adcock, D.M.; Bates, S.M.; Douxfils, J.; Favaloro, E.J.; Gouin-Thibault, I.; Guillermo, C.; Kawai, Y.; Lindhoff-Last, E.; Kitchen, S. International Council for Standardization in Haematology (ICSH) Recommendations for Laboratory Measurement of Direct Oral Anticoagulants. Thromb. Haemost. 2018, 118, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripodi, A.; Ageno, W.; Ciaccio, M.; Legnani, C.; Lippi, G.; Manotti, C.; Marcucci, R.; Moia, M.; Morelli, B.; Poli, D.; et al. Position Paper on laboratory testing for patients on direct oral anticoagulants. A Consensus Document from the SISET, FCSA, SIBioC and SIPMeL. Blood Transfus. 2018, 16, 462–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harenberg, J.; Martini, A.; Du, S.; Kramer, S.; Weiss, C.; Hetjens, S. Performance Characteristics of DOAC Dipstick in Determining Direct Oral Anticoagulants in Urine. Clin. Appl. Thromb. Hemost. 2021, 27, 1076029621993550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margetic, S.; Celap, I.; Huzjan, A.L.; Puretic, M.B.; Goreta, S.S.; Glojnaric, A.C.; Brkljacic, D.D.; Mioc, P.; Harenberg, J.; Hetjens, S.; et al. DOAC Dipstick Testing Can Reliably Exclude the Presence of Clinically Relevant DOAC Concentrations in Circulation. Thromb. Haemost. 2022, 122, 1542–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harenberg, J.; Schreiner, R.; Hetjens, S.; Weiss, C. Detecting Anti-IIa and Anti-Xa Direct Oral Anticoagulant (DOAC) Agents in Urine using a DOAC Dipstick. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2019, 45, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harenberg, J.; Beyer-Westendorf, J.; Crowther, M.; Douxfils, J.; Elalamy, I.; Verhamme, P.; Bauersachs, R.; Hetjens, S.; Weiss, C.; Working Group, M. Accuracy of a Rapid Diagnostic Test for the Presence of Direct Oral Factor Xa or Thrombin Inhibitors in Urine-A Multicenter Trial. Thromb. Haemost. 2020, 120, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, J.L.; Reaves, A.B.; Tolley, E.A.; Oliphant, C.S.; Hutchison, L.; Alabdan, N.A.; Sands, C.W.; Self, T.H. Comparison of initial warfarin response in obese patients versus non-obese patients. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 2013, 36, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, S.; Palareti, G.; Legnani, C.; Dellanoce, C.; Cini, M.; Paoletti, O.; Ciampa, A.; Antonucci, E.; Poli, D.; Morandini, R.; et al. Thrombotic events associated with low baseline direct oral anticoagulant levels in atrial fibrillation: The MAS study. Blood Adv. 2024, 8, 1846–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palareti, G.; Testa, S.; Legnani, C.; Dellanoce, C.; Cini, M.; Paoletti, O.; Ciampa, A.; Antonucci, E.; Poli, D.; Morandini, R.; et al. More early bleeds associated with high baseline direct oral anticoagulant levels in atrial fibrillation: The MAS study. Blood Adv. 2024, 8, 4913–4923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, L.; Hetjens, S.; Fareed, J.; Auge, S.; Tredler, L.; Harenberg, J.; Weiss, C.; Elalamy, I.; Gerotziafas, G.T. Comparison of the DOAC Dipstick Test on Urine Samples with Chromogenic Substrate Methods on Plasma Samples in Outpatients Treated with Direct Oral Anticoagulants. Clin. Appl. Thromb. Hemost. 2023, 29, 10760296231179684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ord, L.; Marandi, T.; Mark, M.; Raidjuk, L.; Kostjuk, J.; Banys, V.; Krause, K.; Pikta, M. Evaluation of DOAC Dipstick Test for Detecting Direct Oral Anticoagulants in Urine Compared with a Clinically Relevant Plasma Threshold Concentration. Clin. Appl. Thromb. Hemost. 2022, 28, 10760296221084307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrelaar, A.E.; Bogl, M.S.; Buchtele, N.; Merrelaar, M.; Herkner, H.; Schoergenhofer, C.; Harenberg, J.; Douxfils, J.; Siriez, R.; Jilma, B.; et al. Performance of a Qualitative Point-of-Care Strip Test to Detect DOAC Exposure at the Emergency Department: A Cohort-Type Cross-Sectional Diagnostic Accuracy Study. Thromb. Haemost. 2022, 122, 1723–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Anti-IIa I (n: 26) | Anti-Xa I (n: 134) | Overall (n: 160) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean) | 73.4 ± 7 | 73.1 ± 9 | 73.1 ± 9 | 0.718 |

| Female (%) | 23.1 | 35.8 | 33.8 | 0.209 |

| Dipstick positive (%) | 92.3 | 95.5 | 95.0 | 0.491 |

| Hypertension (%) | 96.2 | 94.8 | 95.0 | 0.768 |

| Diabetes (%) | 46.2 | 38.1 | 39.4 | 0.439 |

| Previous MI (%) | 34.6 | 18.7 | 21.3 | 0.069 |

| Previous stroke/TIA (%) | 38.5 | 13.4 | 17.5 | 0.002 |

| Smoke (%) | 7.7 | 12.7 | 11.9 | 0.471 |

| Ex-smoke (%) | 57.7 | 41.0 | 43.8 | 0.117 |

| COPD (%) | 19.2 | 20.9 | 20.6 | 0.848 |

| PAD (%) | 15.4 | 5.2 | 6.9 | 0.061 |

| HF (%) | 34.6 | 21.6 | 23.8 | 0.155 |

| Liver disease (%) | 11.5 | 11.9 | 11.9 | 0.954 |

| Cancer (%) | 11.5 | 17.2 | 16.3 | 0.477 |

| BMI < 35 (%) | 57.7 | 76.9 | 73.8 | 0.042 |

| BMI ≥ 35 (%) | 42.3 | 23.1 | 26.3 | |

| CHA2DS2-VASc Score | 4.5 ± 1.8 | 3.8 ± 1.5 | 3.9 ± 1.6 | 0.099 |

| HAS-BLED score | 1.3 ± 0.8 | 1.2 ± 0.7 | 1.2 ± 0.7 | 0.344 |

| Therapy | ||||

| Antiplatelet (%) | 0.0 | 4.5 | 3.8 | 0.271 |

| ACE inhibitors/ARBs (%) | 84.6 | 70.9 | 73.1 | 0.149 |

| Nitro-derivates (%) | 0.0 | 3.0 | 2.5 | 0.372 |

| Beta-blockers (%) | 73.1 | 74.6 | 74.4 | 0.868 |

| Digoxin (%) | 11.5 | 9.0 | 9.4 | 0.679 |

| Antiarrhythmics (%) | 11.5 | 23.9 | 21.9 | 0.164 |

| Amiodarone (%) | 3.8 | 6.0 | 5.6 | 0.667 |

| Statins (%) | 76.9 | 74.6 | 75.0 | 0.805 |

| Ezetimibe (%) | 26.9 | 23.9 | 24.4 | 0.741 |

| SSRI (%) | 11.5 | 6.7 | 7.5 | 0.393 |

| Diuretics (%) | 61.5 | 64.2 | 63.7 | 0.798 |

| PPI (%) | 53.8 | 61.9 | 60.6 | 0.439 |

| Allopurinol (%) | 7.7 | 19.4 | 17.5 | 0.150 |

| Clinical Features | ||||

| BMI (continuous) | 33.8 ± 3.6 | 33.7 ± 4 | 33.7 ± 3.9 | 0.897 |

| I Class (%) | 57.7 | 76.9 | 73.8 | 0.026 |

| II Class (%) | 38.5 | 15.7 | 19.4 | |

| ≥III Class (%) | 3.8 | 7.5 | 6.9 | |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 120 ± 10 | 119 ± 12 | 119 ± 12 | 0.624 |

| Hip circumference (cm) | 118 ± 10 | 19 ± 10 | 119 ± 10 | 0.293 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 127 ± 15 | 130 ± 15 | 129 ± 15 | 0.817 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 76 ± 6 | 77 ± 9 | 77 ± 9 | 0.863 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.4 | 1.1 ± 0.4 | 0.668 |

| GOT (IU/L) | 20 ± 7 | 22 ± 10 | 21 ± 10 | 0.487 |

| GPT (IU/L) | 20 ± 11 | 21 ± 12 | 21 ± 12 | 0.708 |

| Value | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity (%) | 99.24 | 95.82–99.98 |

| Specificity (%) | 6.89 | 0.85–22.76 |

| Positive Likelihood Ratio | 1.07 | 0.96–1.18 |

| Negative Likelihood Ratio | 0.11 | 0.01–1.18 |

| Positive Predictive Value (%) | 82.8 | 81.33–84.18 |

| Negative Predictive Value (%) | 66.67 | 15.79–95.52 |

|

True Positive (n: 130) |

False Positive (n: 27) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean) | 73.8 ± 9.0 | 70.5 ± 9.7 | 0.405 |

| Female (%) | 33.6 | 40.0 | 0.537 |

| Hypertension (%) | 93.9 | 100.0 | 0.205 |

| Diabetes (%) | 38.2 | 44.0 | 0.584 |

| Previous MI (%) | 22.1 | 20.0 | 0.812 |

| Previous stroke/TIA (%) | 14.5 | 32.0 | 0.034 |

| Smoke (%) | 12.2 | 8.0 | 0.546 |

| Ex-smoke (%) | 45.0 | 40.0 | 0.642 |

| COPD (%) | 19.1 | 24.0 | 0.572 |

| PAD (%) | 6.1 | 12.0 | 0.292 |

| HF (%) | 26.0 | 12.0 | 0.133 |

| Liver disease (%) | 11.5 | 12.0 | 0.937 |

| Cancer (%) | 17.6 | 12.0 | 0.494 |

| BMI < 35 (%) | 77.9 | 60.0 | 0.059 |

| BMI ≥ 35 (%) | 22.1 | 40.0 | |

| CHA2DS2-VASc Score | 3.9 ± 1.6 | 4.1 ± 1.6 | 0.977 |

| HAS-BLED score | 1.2 ± 0.7 | 1.1 ± 0.7 | 0.591 |

| Therapy | |||

| Antiplatelet (%) | 4.6 | 0.0 | 0.275 |

| ACE inhibitors/ARBs (%) | 73.1 | 72.0 | 0.912 |

| Nitro-derivates (%) | 3.8 | 8.0 | 0.355 |

| Beta-blockers (%) | 72.5 | 80.0 | 0.436 |

| Digoxin (%) | 7.6 | 16.0 | 0.317 |

| Antiarrhythmics (%) | 23.4 | 16.0 | 0.413 |

| Amiodarone (%) | 7.1 | 0.0 | 0.179 |

| Statins (%) | 73.3 | 80.0 | 0.481 |

| Ezetimibe (%) | 22.9 | 32.0 | 0.331 |

| SSRI (%) | 7.8 | 4.2 | 0.532 |

| Diuretics (%) | 62.6 | 72.0 | 0.369 |

| PPI (%) | 62.6 | 52.0 | 0.320 |

| Allopurinol (%) | 17.6 | 16.0 | 0.850 |

| Clinical Features | |||

| BMI (continuous) | 33.3 ± 3.8 | 35.3 ± 4.6 | 0.317 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 118.9 ± 11.8 | 121.5 ± 11.7 | 0.588 |

| Hip circumference (cm) | 118.6 ± 10.0 | 122.0 ± 12.4 | 0.327 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 130.0 ± 15.7 | 126.2 ± 11.0 | 0.214 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 77.4 ± 8.9 | 76.0 ± 8.7 | 0.864 |

| GOT (IU/L) | 21.7 ± 9.7 | 19.7 ± 8.3 | 0.625 |

| GPT (IU/L) | 20.5 ± 12.0 | 20.3 ± 11.2 | 0.515 |

| Trough plasma concentrations (ng/mL) | 88.1 ± 57.8 | 13.0 ± 14.9 | 0.588 |

| Peak plasma concentrations (ng/mL) | 202.1 ± 98.4 | 117.9 ± 102.5 | 0.327 |

| Anti-Xa Inhibitors | Dabigatran | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | 95% CI | Value | 95% CI | |

| Sensitivity (%) | 100 | 79.4–100 | 99.1 | 95.3–99.9 |

| Specificity (%) | 10.0 | 0.25–44.5 | 5.3 | 0.13–26.0 |

| PLR | 1.1 | 0.90–1.37 | 1.05 | 0.94–1.16 |

| NLR | 0 | 0.16 | 0.01–2.5 | |

| PPV (%) | 64.0 | 59.1–68.6 | 86.3 | 85.0–87.6 |

| NPV (%) | 100 | 2.5–100 | 50 | 6.1–93.9 |

| Trough Plasma Concentrations 30 ng/mL | ||

|---|---|---|

| Value | 95% CI | |

| Sensitivity (%) | 99.1 | 95.4–100 |

| Specificity (%) | 4.7 | 0.6–16.2 |

| PLR | 1.04 | 0.97–1.12 |

| NLR | 0.18 | 0.02–1.91 |

| PPV (%) | 74.5 | 73.2–75.8 |

| NPV (%) | 66.7 | 15.7–95.6 |

| Accuracy (%) | 74.4 | 66.9–81 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pannunzio, A.; Castellani, V.; Baldacci, E.; Cammisotto, V.; Mormile, R.; Palumbo, I.M.; Porcu, N.; Chistolini, A.; Bernardini, G.; Menichelli, D.; et al. Diagnostic Performance of a DOAC Urine Dipstick in Obese Outpatients with Atrial Fibrillation: Comparison with Plasma Concentrations. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 466. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020466

Pannunzio A, Castellani V, Baldacci E, Cammisotto V, Mormile R, Palumbo IM, Porcu N, Chistolini A, Bernardini G, Menichelli D, et al. Diagnostic Performance of a DOAC Urine Dipstick in Obese Outpatients with Atrial Fibrillation: Comparison with Plasma Concentrations. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(2):466. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020466

Chicago/Turabian StylePannunzio, Arianna, Valentina Castellani, Erminia Baldacci, Vittoria Cammisotto, Rosaria Mormile, Ilaria Maria Palumbo, Nicola Porcu, Antonio Chistolini, Graziella Bernardini, Danilo Menichelli, and et al. 2026. "Diagnostic Performance of a DOAC Urine Dipstick in Obese Outpatients with Atrial Fibrillation: Comparison with Plasma Concentrations" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 2: 466. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020466

APA StylePannunzio, A., Castellani, V., Baldacci, E., Cammisotto, V., Mormile, R., Palumbo, I. M., Porcu, N., Chistolini, A., Bernardini, G., Menichelli, D., Pastori, D., Harenberg, J., Violi, F., & Pignatelli, P. (2026). Diagnostic Performance of a DOAC Urine Dipstick in Obese Outpatients with Atrial Fibrillation: Comparison with Plasma Concentrations. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(2), 466. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020466